Abstract

Schizaphis graminum (Rondani), commonly known as the greenbug, is a major pest of cereal crops. It causes significant yield losses through direct phloem feeding and efficient transmission of crop viruses. Despite its agricultural importance, genomic resources for S. graminum have remained limited, hindering in-depth studies of its rapid environmental adaptation, insecticide resistance, and exceptional virus-vectoring capacity. Here, we present the first high-quality, chromosome-level genome assembly for S. graminum. The assembled genome spans 380.30 Mb, with 379.43 Mb (99.77%) successfully anchored to four pseudochromosomes. It exhibits high continuity, with scaffold and contig N50 values of 105.17 Mb and 48.79 Mb, respectively, and a BUSCO completeness of 97.10%. This genomic assembly provides a valuable resource for comparative genomics, evolutionary studies, and functional studies in aphids. It also establishes a foundation for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying virulence, host specialization, and virus transmission in S. graminum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Schizaphis graminum (Rondani), the greenbug, is a major pest of cereal crops such as wheat, barley, sorghum, and several wild grasses, causing severe direct damage by phloem feeding that leads to leaf chlorosis and plant stunting1. It exhibits a complex life history with cyclical parthenogenesis, typically reproducing viviparously for multiple generations during the crop-growing season and switching to sexual reproduction to produce overwintering eggs in winter. The insect pest causes substantial yield losses through direct feeding damage and, more notably, by serving as an efficient vector of barley yellow dwarf viruses (BYDV)2,3,4. The greenbug feeds on the phloem sap from hosts such as wheat and oats (Fig. 1). Infestations typically originate on the lower leaves and progressively advance upward to the younger foliage. Dense colonies on the abaxial leaf surface, accompanied by extensive honeydew secretion, inhibit photosynthesis and disrupt normal plant growth. Symptoms include leaf reddening, reduced spike size, impaired grain filling, and in severe cases, complete sterility, resulting in shriveled kernels. Such damage substantially compromises both the yield and quality of affected crops5,6.

Recent advances in high-quality genome assemblies of aphids, such as Aphis glycines7, Brevicoryne brassicae8 and Therioaphis trifolii9, have greatly enhanced our understanding of aphid biology, particularly in areas such as polyphenism, host adaptation, and insecticide resistance. However, genomic resources for S. graminum have remained limited, hindering the elucidation of the genetic mechanisms governing its rapid adaptation to agricultural environments, the development of insecticide resistance, and its highly efficient vectoring capacity10. The population dynamics and pest severity of S. graminum are strongly shaped by abiotic stresses, such as drought, temperature extremes, and chemical control practices11. Transcriptomic studies have implicated key gene families involved in stress responses, such as cytochrome P450s and cuticular proteins5,12. However, the lack of a chromosome-level reference genome has impeded comprehensive genome-wide analyses of these gene families, their evolutionary trajectories, and their regulatory mechanisms controlling their expressions.

Here, we present the first high-quality, chromosome-level genome assembly of S. graminum, which offers a robust platform for comparative genomic and functional analyses. Based on this assembly, we systematically identified and characterized expanded gene families implicated in insecticide metabolism and environmental adaptation. The final assembled genome spans 380.30 Mb, with 379.43 Mb (99.77%) anchored to four pseudochromosomes. The assembly exhibits high continuity, as reflected in scaffold and contig N50 values of 105.17 Mb and 48.79 Mb, respectively, and a BUSCO completeness score of 97.10%.

This chromosome-scale genome assembly provides critical insights into the genomic architecture underlying the pest status of S. graminum in cereal crops. It establishes a valuable resource for elucidating the molecular mechanisms of host specialization, particularly on wheat, oat, and barley, and facilitates the development of RNA interference-based management strategies. Collectively, this genomic dataset offers a foundational platform for investigating the molecular basis of aphid virulence, insecticide resistance, and virus transmission, thereby supporting the design of sustainable pest management strategies.

Methods

Sample collection and rearing

The lab-reared colonies of S. graminum used in this study were originally collected from Yangling City, Shanxi Province, China (34°27′27″N, 108°08′11″E) in 2016. Subsequently, these aphids were maintained on common oats (Avena sativa) under controlled conditions of 26 ± 1 °C, a photoperiod of 16 h light and 8 h darkness, and a relative humidity of 65 ± 5%.

Adult S. graminum were first transferred to culture dishes and starved for 24 h under controlled laboratory conditions. This treatment was applied to eliminate plant-derived materials and reduce transient microorganisms from gut contents, ensuring that the sequencing data accurately represent the endogenous gene expression of the aphids rather than transcripts originating from the host plant. Approximately 1000 live individuals were then collected for Illumina, PacBio HiFi, and Hi-C sequencing, respectively. In addition, 500 winged and wingless adults were selected, rapidly flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for ONT sequencing.

Genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method. For PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing, libraries were prepared with the SMRTbell® Express Template Prep Kit 3.0 (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA) targeting an insert size of ~20 kb. High-quality DNA samples were sheared into ~10 kb fragments using a Megaruptor B06010001 (Diagenode, Liège, Belgium), concentrated with AMPure® PB Beads (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA), and processed with the SMRTbell 3.0 kit (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA) for library construction. This workflow included removal of single-stranded overhangs, DNA damage repair, end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, and exonuclease digestion. Size selection of SMRTbell libraries was performed using the SageELF ELF000 system (Sage Science, MA, USA). PacBio HiFi 10 kb library preparation was carried out by Berry Genomics Corporation (Beijing, China).

For short-read sequencing, whole-genome libraries were prepared using the Agencourt AMPure XP-Medium Kit (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) with an insert size of 200–400 bp. Libraries were subsequently sequenced on the DNBSEQ-T7 platform. Short-read library construction was also performed by Berry Genomics Corporation (Beijing, China).

Hi-C library construction was performed by Berry Genomics Corporation. The procedure involved formaldehyde cross-linking of chromatin, restriction enzyme digestion, end repair, DNA cyclization, and DNA purification. MboI was used as the restriction enzyme during the digestion step. The integrity and quality of the extracted genomic DNA were assessed using 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis, a NanoDrop One Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The extracted DNA exhibited optimal quality parameters: concentration = 88.2 ng/μL, OD260/280 value = 1.82, and OD260/230 = 2.26.

The sequencing output and depth of coverage are summarized in Table 1.

Genome size estimation

The primary objective of the genome survey analysis was to estimate genome size, heterozygosity, and repeat content, thereby guiding the selection of appropriate assembly strategies and parameter optimization. Raw short-read data generated from the BGI platform were quality-controlled and trimmed using fastp v0.23.413 with the following parameters: -q 20 -D -g -x -u 10 -5 -r -c. Specifically, bases with quality scores below Q20 were discarded, duplicate reads were removed (-D), poly-G/X tails were trimmed (-g -x), reads with more than 10% low-quality bases were filtered out (-u 10), and base correction was performed using overlapping read information (-c).

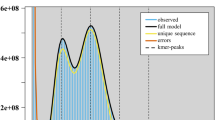

Genome survey analyses were conducted based on the k-mer frequency distribution. K-mer counts were generated using khist.sh (part of the BBTools v38.90 package14, with k-mer size set to 21. Genome features were further analyzed using GenomeScope v2.015 with parameters -k 21 -p 2 -m 10000, where the maximum k-mer coverage cutoff was set to 10,000 (Fig. 2).

Using BBTools, the estimated genome size of S. graminum was 390,080,888 bp with a heterozygosity of 1.79%. The k-mer frequency distribution revealed a heterozygous peak at 44× that was higher than the main peak at 88× , indicating a highly heterozygous genome. These genomic features provide a critical foundation for future in-depth studies on S. graminum, including functional annotation and comparative genomic analyses.

Genome assembly

High-quality HiFi reads were generated using pbccs v6.4.0 (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/ccs). The initial assemblies were produced with Hifiasm v0.24.016 using the parameter ‘-I 3’. Low-depth contigs are likely to represent contaminants or assembly errors; therefore, only contigs with sequencing depth >12× for S. graminum were retained, while contigs below one-tenth of the average sequencing depth were discarded. Given the extremely high quality of the HiFi reads, long contigs exhibited QV scores of approximately 60, and thus additional polishing was not required. To address potential haplotype redundancy in the assemblies arising from heterozygosity in diploid or wild populations, redundant sequences were removed using Purge_dups v1.2.517, which leverages both contig similarity and sequencing depth. Sequence alignments were performed with Minimap2 v2.2918,19 (-x map-hifi for mapping HiFi reads to the assembly; -x asm5 -DP for self-to-self assembly alignment). Purge_dups was run with default parameters (-2 -a 60).

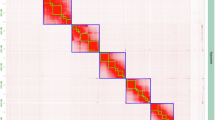

Chromosome-scale scaffolding was achieved using Hi-C data and the YAHS v1.2 pipeline20. Hi-C reads were processed with chromap v0.2.621, including read alignment, duplicate removal, and Hi-C contact extraction. Two rounds of scaffolding were conducted with YAHS using default parameters. The preliminary scaffolds were manually curated with Juicebox v1.11.0822 to correct assembly errors such as misjoins, translocations, and inversions, followed by a second round of YAHS scaffolding to generate the final assembly. Sequencing depth for each pseudochromosome was assessed using SAMtools v1.1023, with alignment files generated by Minimap2 (-ax map-hifi for HiFi reads; -ax sr for short-read WGS data). Hi-C contact maps (Fig. 3) confirmed the high quality of the scaffolding, yielding chromosome-level assemblies of four pseudochromosomes for S. graminum.

Genome completeness was evaluated using BUSCO v5.7.124 with the insecta_odb10 reference dataset (n = 1,367 single-copy orthologs). Additionally, raw short-read genome data and transcriptome reads (both second- and third-generation) were mapped back to the assembled genome to assess data utilization and assembly completeness. Read mapping was performed using Minimap2, and mapping rates were calculated with SAMtools. Potential contaminants in the assembly were identified using MMseqs. 2 v1325 through a BLASTN-like search against the NCBI nt and UniVec databases. Base-level quality scores (QV) and k-mer spectra of the genome were assessed using Merqury v1.326.

The final S. graminum genome assembly metrics are summarized in Table 2. The assembled genome size was 380.30 Mb, which is smaller than those of B. brassicae (429.99 Mb) and T. trifolii (541.25 Mb), but larger than that of A. glycines (324 Mb)7,8,9. The final assembly comprised 13 scaffolds and 37 contigs. The maximum scaffold and contig lengths reached 108.054 Mb and 102.518 Mb, respectively, with scaffold and contig N50 values of 105.17 Mb and 48.793 Mb. The overall GC content was 27.65%, reflecting the high continuity of the assembly. The genome assembly was evaluated using BUSCO, which showed a high completeness of 97.1%. This level of completeness is comparable to or slightly higher than those reported for other aphid species, including A. glycines (97.2%), B. brassicae (96.19%), and T. trifolii (96.6%)7,8,9. The proportion of duplicated BUSCOs was only 3.1%, suggesting minimal redundancy in the assembly.

Four pseudochromosomes accounted for 379.43 Mb of sequence, representing 99.77% of the total assembly. Detailed statistics on chromosome length, sequencing depth, and QV scores are provided in Table 3.

Genome annotation

A species-specific de novo repeat library was constructed using RepeatModeler v2.0.527 with the additional LTR structural search enabled (-LTRStruct), based on both structural features of repetitive elements and de novo prediction. This library was then combined with the Dfam 3.828 and RepBase-2018102629 databases to generate the final reference repeat database. Repeat annotation was performed using RepeatMasker v4.1.530, aligning the assembled genome against the final repeat database to identify and classify repetitive elements.

A total of 746,658 repetitive elements (125,823,370 bp) were identified in the S. graminum genome, corresponding to 33.09% of the assembly, indicative of a genome with a moderate repeat content. This proportion is comparable to those observed in other three aphid species, including A. glycines (32.06%), B. brassicae (32.84%), and T. trifolii (36.86%)7,8,9. The six most abundant repeat classes were classified as follows: Unknown (12.70%), DNA transposons (10.73%), simple repeats (3.52%), LTR retrotransposons (3.16%), LINEs (1.81%), and rolling-circle elements (0.40%). Detailed statistics are provided in Table 4.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which play critical roles in a wide range of biological processes—including transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) that are indispensable for protein biosynthesis—were comprehensively annotated in the genome. The ncRNA annotation was performed using two complementary approaches. First, ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs) were identified through sequence homology searches against the Rfam database using Infernal v1.1.531, which employs covariance models to detect conserved RNA secondary structures. Second, transfer RNA (tRNA) genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE v2.0.1232 with default parameters. To improve annotation accuracy, low-confidence tRNA predictions were excluded using the built-in EukHighConfidenceFilter script (Table 5).

The MAKER v3.01.0433 annotation pipeline predicted 13,659 protein-coding genes in S. graminum, with an average gene length of 11,989.0 bp. Genes comprised an average of 7.6 exons (mean length 310.3 bp) and 6.6 introns (mean length 1,582.8 bp). On average, 7.2 coding sequences (CDSs) were identified per gene, with a mean CDS length of 217.6 bp (Table 6).

Functional annotations were systematically assigned to all predicted genes by integrating evidence from seven major biological databases: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)34, UniProt35, Gene Ontology (GO)36 and InterPro37. For the S. graminum genome, 13,569 genes (99.34%) matched entries in the UniProtKB database. InterPro analysis identified protein domains in 10,573 protein-coding genes, which is fewer than those reported in three other aphid species, A. glycines (20,781 genes), B. brassicae (22,671 genes), and T. trifolii (13,684 genes)7,8,9. In addition, integrated InterPro and eggNOG-mapper annotations assigned GO terms to 9,390 genes and KEGG pathway entries to 4,668 genes (Table 7). A circos plot integrating genome structure and annotation was generated using TBTools-II v2.0963338. The results revealed that the longest chromosome measured 108.05 Mb, whereas the shortest was 62.85 Mb (Fig. 4).

Although this study provides a high-quality genomic resource for S. graminum, it is based on a single geographical population collected from Yangling, Shaanxi Province. Therefore, potential genetic differentiation among populations from different regions was not considered. Future studies incorporating genomic data from multiple wheat-producing areas, such as North China and Northwest China, will be essential to elucidate the population genetic structure and adaptive divergence of S. graminum, thereby improving the representativeness and applicability of the genomic resource.

Data Records

The genome sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession number PRJNA1282330. The PacBio, illumina DNA short reads, Hi-C sequencing and transcriptome data used for the genome assembly have been deposited with the accession numbers SRR3555301739, SRR3555301840, SRR3555301641 and SRR3555301542. Genome assembly has been deposited at the NCBI under the accession number of JBPJBB00000000043. The genome annotation files are available in the Figshare database44.

Technical Validation

Two approaches were employed to evaluate the quality of the genome assembly. First, genome completeness was assessed using BUSCO v5.7.1 with the insect_odb10 database (n = 1,367). The S. graminum assembly achieved a BUSCO completeness of 97.0%, consisting of 76.7% single-copy, 20.3% duplicated, 0.3% fragmented, and 2.7% missing BUSCOs. Second, assembly accuracy was evaluated by mapping PacBio, Illumina, and RNA-seq reads to the genome, yielding mapping rates of 99.51%, 95.69%, and 64.39%, respectively. Together, these results demonstrate the high quality and reliability of the assembled genome.

Data availability

The sequencing datasets produced in this study can be accessed through the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession PRJNA1282330. Specifically, the PacBio, Illumina short-read data, Hi-C data, and transcriptome data used for genome assembly are available under accession numbers SRR35553017, SRR35553018, SRR35553016, and SRR35553015, respectively. Genome assembly has been deposited at the NCBI under the accession number of JBPJBB000000000. Genome annotation files have been deposited in Figshare and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30215485.

Code availability

All bioinformatics analyses in this study were performed following standardized protocols as specified in the official documentation of the respective software packages. No custom scripts, proprietary algorithms, or non-standard code implementations were used at any stage of the study.

References

Li, X. A. et al. Sublethal and transgenerational effects of flonicamid on biological traits and related genes in the wheat aphid, Schizaphis graminum (Rondani). Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 23, 102224 (2025).

Stephen N, W., Hein, G. L. Yellow Dwarf of Wheat,Barley, and Oats. (2013).

Jiao, Z. et al. Sorghum aphid/greenbug: current research and control strategies to accelerate the breeding of aphid-resistant sorghum. Front Plant Sci 16, 1588702 (2025).

Jarošová, J., Beoni, E. & Kundu, J. K. Barley yellow dwarf virus resistance in cereals: Approaches, strategies and prospects. Field Crops Research 198, 200–214 (2016).

Zhang, B. Z. et al. Differential expression of genes in greenbug (Schizaphis graminum Rondani) treated by imidacloprid and RNA interference. Pest Manag Sci 75, 1726–1733 (2019).

Gao, J. R. & Zhu, K. Y. Increased expression of an acetylcholinesterase gene may confer organophosphate resistance in the greenbug, Schizaphis graminum (Homoptera: Aphididae). Pestic Biochem Phys 73, 164–173 (2002).

Qiu, S., Wu, N., Sun, X., Xue, Y. & Xia, J. Chromosome-level genome assembly of soybean aphid. Scientific Data 12, 386 (2025).

Wu, J. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the cabbage aphid Brevicoryne brassicae. Scientific Data 12, 167 (2025).

Huang, T. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the spotted alfalfa aphid Therioaphis trifolii. Scientific Data 10, 274 (2023).

Bass, C. & Nauen, R. The molecular mechanisms of insecticide resistance in aphid crop pests. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 156, 103937 (2023).

Ahmadpour, R. et al. Nanoformulation of imidacloprid insecticide with biocompatible materials and its ecological and physiological effects on wheat green aphid, Schizaphis graminum Rondani. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 27, 102332 (2024).

Liu, J. J. et al. De novo assembly of the transcriptome for Greenbug (Schizaphis graminum Rondani) and analysis on insecticide resistance‐related genes. Entomological Research 49, 363–373 (2019).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, 1884–1890 (2018).

Bushnell, B. BBMap. https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/.

Ranallo-Benavidez, T., Rhyker Jaron, S. K. & Schatz, C. M. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nature Communications 11, 1432 (2020).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36, 2896–2898 (2020).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Li, H. New strategies to improve minimap2 alignment accuracy. Bioinformatics 37, 4572–4574 (2021).

Zhou, C., McCarthy, S. A. & Durbin, R. YaHS: yet another Hi-C scaffolding tool. Bioinformatics 39, btac808 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Fast alignment and preprocessing of chromatin profiles with Chromap. Nat Commun 12, 6566 (2021).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell Syst 3, 95–98 (2016).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10, 1–4 (2021).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simao, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Mol Biol Evol 38, 4647–4654 (2021).

Steinegger, M. & Söding, J. MMseqs. 2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nature Biotechnology 35, 1026–1028 (2017).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol 21, 245 (2020).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 9451–9457 (2020).

Storer, J., Hubley, R., Rosen, J., Wheeler, T. J. & Smit, A. F. The Dfam community resource of transposable element families, sequence models, and genome annotations. Mob DNA 12, 1–14 (2021).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935 (2013).

Chan, P. P. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE: Searching for tRNA Genes in Genomic Sequences. Methods Mol Biol. 1962, 1–14 (2019).

Bao, W., Kojima, K. K. & Kohany, O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob DNA 6, 1–6 (2015).

Smit, A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0. http://www.repeatmasker.org (2013-2015).

Holt, C. & Yandell, M. MAKER2: An annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 491 (2011).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 28, 27–30 (2020).

Consortium, T. U. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res 45, 158–169 (2017).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 25, 25–29 (2000).

Blum, M. et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D344–D354 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol Plant 16, 1733–1742 (2023).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35553017 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35553018 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35553016 (2025).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR35553015 (2025).

NCBI GenBank https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_053477495.1 (2025).

Zhang, H. H. The genome annotation of Schizaphis graminum. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30215485 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Maohua Chen (Northwest A&F University) for providing the Schizaphis graminum samples. We thank Prof. Feng Zhang (Nanjing Agricultural University) for his valuable assistance with genome data analysis. We also acknowledge the Nanjing Agricultural University Bioinformatics for their essential support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W.L., K.J.L. and H.H.Z. designed the study. C.T.S. and J.T.W. collected and reared S. graminum. W.Q.C. conducted the bioinformatics analyses. H.H.Z. wrote the original draft manuscript. J.T.W. and Z.W.L. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Shi, C., Chen, W. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the greenbug, Schizaphis graminum. Sci Data 13, 114 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06431-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06431-5