Abstract

Research on the ionospheric Spread-F (SF) phenomenon holds significant value in both fields as ionospheric electrodynamic research and enhanced operational applications in radio-based technologies (e.g., communication and navigation). To date, the classification of Spread-F remains largely reliant on the manual interpretation of ionograms by experts, suffering from inefficiency (~10 seconds per figure) and subjectivity. There has been no publicly available ionogram dataset classifying Frequency/Range/Mix/Strong Range SF (FSF/RSF/MSF/SSF) by either human labor or machine processing. To address this problem, we introduce the first open, expert-guided ionogram dataset that is simultaneously the most comprehensive in terms of class coverage, the largest in volume, and the most extensive in temporal span. This collection encompasses 150,000 ionograms (30,000 per class, including a “non-SF” group) spanning 14 years from 2002 to 2016, thereby capturing a diverse range of solar and geomagnetic conditions. The attached classification SA-ResNet50 model based on this dataset could be applied to further data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The ionogram is a radar (ionosonde) echo graph, which can measure the vertical conditions of the ionosphere, because when the frequency of the transmitted radio wave matches the plasma frequency in the ionosphere, the signal will be reflected. The ionogram is illustrated as frequency vs virtual height. The continuously returned signals form distinct curves known as the E- and F-traces, corresponding to the plasma density profile.

One of the most significant phenomena captured in ionograms is the Spread-F (SF). As the dispersion characteristics of the F region in the ionogram, Spread-F is believed to be caused by plasma density disturbances such as fluctuations and irregularities. This dispersion in the echo graph is normally a result of different frequencies being reflected at the same height or the same frequency being reflected at multiple heights, indicating the fine structure of the ionospheric plasma. Therefore, the image features of Spread-F are associated with ionospheric electrodynamic processes, corresponding to different physical mechanisms, such as irregularities (for example, bubbles and blobs)1,2, Traveling Ionospheric Disturbance (TID)3, polar particle precipitation4,5, and so on. Through the graph features of an ionogram, researchers could infer many physical processes.

Especially at low latitudes, Equatorial spread F (ESF) has been observed for nearly 80 years6, but it remains unknown on the physical mechanisms of why it forms on a given night7,8. One important factor for ESF production is the large-scale zonal electric fields near the day/night terminator. These electric fields produce the vertical E × B plasma drifts that raise and lower the ionosphere, while the strength and timing of this Evening Prereversal Enhancement (EPE) have been proven to be closely associated with the occurrence of ESF1,9,10. There are still some other mechanisms, such as meridional wind effects11,12, large-scale wave structure of bottomside ionosphere13,14, seed perturbation15,16, and so on17. None of them could correspond to all the ESF events. Maybe the different ESF types defined by graph features give further help to distinguish these mechanisms.

The ESF has long been classified only through manual labels. Chandra and Rastogi18 classified ESF into two distinct types: (1) range spread-F (RSF), characterized by horizontal diffusiveness in F-layer traces during post-sunset hours while preserving identifiable critical frequencies, and (2) frequency spread-F (FSF), occurring post-midnight with maximal spreading near critical frequencies that obscures foF2 determination. They mentioned complete spreading, where ambiguities extend to both range and critical frequency, occasionally manifesting. Later, these complete spreadings were further defined as (3) mixed Spread-F (MSF)4 and (4) Strong Range Spread-F (SSF)19. Studies on the manual label ESF of ionograms found that SSF takes a large proportion in Asia19,20,21,22, South America23,24,25, Africa26, Oceania27, and even midlatitude during magnetic storms28.

These irregularities are interconnected across equatorial and low-latitude regions via plasma fountain mechanisms analogous to those driving the equatorial ionization anomaly. Besides, there have been some studies that implied that the occurrences of different SF types had different variation features with local time, season, solar/magnetic activities, and other factors. For example, Wang et al.20 found that the RSF and SSF occurrence maximum at Hainan station are most frequent during the equinoctial months during solar maximum years, and the occurrence rates are increasing with SunSpot Number (SSN). On the other hand, the FSF and MSF occurrence maxima are most frequent during the summer months, and the occurrence rates are decreasing with SSN. Wang et al.29 found that the occurrence percentage of FSF is higher than that of RSF, of which the former is anti-correlated with solar or geomagnetic activities. The maximum of the FSF occurrence percentages mostly appeared between 01:00 and 02:00 LT, approximately, whereas that of RSF appeared near 00:00 LT. Xie et al.30 proposed a statistically significant correlation between the presence of valley region irregularities and that of ESF over Sanya. Wang et al.29 compared the SF at Fuke, Xiamen, Nanning, Kezhou, Geermu, Xi’an, Beijing, and Mohe in 2011. The maximum spread-F occurrence decreases with increasing latitude, and the time of spread-F occurrence maximum also delays with increasing latitude. The ESF occurrences also have longitudinal effects, as Cueva et al.31 showed that the onset of ESF and plume events at Christmas Island occurred 2–3 hours later than at São Luís and Jicamarca.

The ESF classification is important to learn the physical mechanism in the ionosphere, but artificial recognition requires a significant amount of time and labor. Usually, considering software loading and file switching, a proficient researcher needs about 10 seconds to judge the ESF from one original RSF/GRM format image, based on experience and a little imagination to supplement some missing parts caused by noise. To do the statistical study on ESF with a 15-minute resolution during one year at one site, even skilled researchers need to spend at least 100 hours or so to obtain reliable records.

Therefore, some auto-detection/classification methods have been developed to improve the efficiency. For example, Thammavongsy et al.32,33 developed a specialized Levenberg-Marquardt backpropagation (LM-BP) algorithm to isolate Range Spread-F (RSF) from Chumphon. With a naive Bayesian classifier, Feng et al.34 did a statistical analysis of SF from Mohe, I-Cheon, Jeju, Wuhan, and Sanya ionograms. In their results, the SF had different seasonal variations, and occurred more easily in the post-midnight hours when compared with the pre-midnight period. In particular, SSF reached its maximum at the equinox in Sanya. With an automated method of spread F detection using pattern recognition and edge detection for low latitude regions, Bhaneja et al.35 did a statistical analysis of low latitude SF from Jicamarca from 2001 to 2016, Ascension Island from 2000 to 2014, and Kwajalein from 2004 to 2012. Although significant variation was not observed over the solar cycle, the different longitudes and declination angles contributed to the ionospheric variations over the seasonal cycle. These results are consistent with the previous studies with manual labels.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have enabled automatic detection and classification methods to closely replicate human judgment and intuition, significantly reducing the inherent subjectivity associated with traditional empirical operations. Numerous studies demonstrate that AI-driven models, when provided with sufficiently extensive and diverse training datasets, can match, or even surpass expert-based heuristic methods, while ensuring rapid inference capabilities suitable for real-time applications. Lan et al.36 introduced a decision tree (DTs)- based framework for identifying SF at Wuhan, later refining their approach with a convolutional neural network (CNN)37. At Jicamarca, Luwanga et al.38 implemented pre-trained architectures (VGG16, InceptionV3, ResNet50) for categorizing ionograms into SF-present and non-SF. Rao et al.39 developed a typical expert system to auto-detect both sporadic E (Es) and SF from the low-latitude Hyderabad in 2015. The algorithm processed raw ionogram files (*.md4) by reading frequency-indexed height points (bins) to identify ionospheric events. This model could classify the ESF, achieving 96.71% for Es, 89.71% for RSF, and 93.39% for SSF. Wang et al.40 proposed a supervised-learning method for analyzing ionograms recorded at Hainan between 2002 and 2015, achieving an overall accuracy greater than 92% in classifying equatorial spread-F (ESF) into the FSF, RSF, MSF, and SSF types. The processing time per ionogram was reduced to less than 100 ms. Compared with the typical expert system of Rao et al.39, this CNN method reduced artificial regulations. Benchawattananon et al.41 combined CNN with an SVM-based approach to make the ESF classification by using 4,692 labeled ionograms at Chumphon. The model achieved 98.0% for no SF, 85.1% for FSF, 90.7% for RSF, 66.7% for SSF, and 99.2% for an unidentified class. This unidentified class reduced practicality. One common feature of these AI-driven classification methods is that their effectiveness still fundamentally depends on the accessibility and quantity of the manually annotated sample datasets. Therefore, all abovementioned approaches invariably confront an obvious limitation: the number of expert-labeled samples is seriously insufficient. This scarcity inevitably casts doubt upon the generalizability of AI models trained via these methods. Consequently, this question empirically underscores the paramount importance of possessing large-scale, expert-annotated datasets for enabling effective deep learning paradigms.

In summary, the ESF classification is important to learn the physical mechanism in the ionosphere, and the AI method could obviously improve efficiency and reduce subjectivity. Therefore, it is imperative to build a relatively large, open-access, and expert-guided ionogram dataset with multiple categories. In this work, we further refined the processing of ionograms from the Hainan Fuke ionosonde station and established an ESF classification dataset over one solar cycle, covering every conceivable ionospheric condition at one low-latitude station. This dataset comprises 5 categories: non-SF, SSF, RSF, MSF, and FSF, with 30,000 samples for each type, resulting in a total of 150,000 ionograms. By delivering both scale and balance, we hope this dataset can serve as a benchmark for training and evaluating next-generation ESF detection and classification algorithms.

Methods

The following sections detail the entire process of constructing the ionogram dataset. It includes ionogram acquisition, data preprocessing and augmentation, classification model training, and manual validation to finalize the ionogram dataset.

Data acquisition

The ionograms utilized in this study were acquired by the Digital Portable Sounder-4D (DPS-4D Digisonde) deployed at the Hainan National Field Science Observation and Research Station for Space Weather (geographic coordinates: 19.5°N, 109.1°E; magnetic latitude: 11°N), a key facility of the Chinese Meridian Project. As illustrated in Fig. 1(a), the raw ionogram images have dimensions of 700 pixels in height and 600 pixels in width and are stored as PNG files. These ionograms span 15 years from 2002 to 2016, with temporal coverage extending through an entire solar cycle (Solar Cycle 23 to early Cycle 24). The majority of observations were obtained at the 15-minute temporal resolution, except during periods of instrument downtime for maintenance or calibration. After rigorous quality control, excluding malfunction-induced data gaps, the final curated collection comprises 517,331 validated ionospheric records.

The classification labels for all ionograms were manually annotated by researchers at the National Space Science Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, through years of dedicated effort. These labels are organized in annual sets, with each year’s annotations archived in dedicated “YYYY[SF].txt” text files where YYYY denotes the 4-digit Gregorian year. Therefore, this approach generates 15 annual label files spanning the 2002–2016 observation period. As shown in Fig. 1(b), the file represents the manually classified results for the exemplified year 2010.

In the “2010SF” file, the first column records the occurrence date of Spread-F events in day-of-year (DOY) format. For example, “071” denotes the 71st day of 2010 (March 21, 2010). The second and third columns respectively document the event’s start and end times in 24-hour notation, while the fourth column employs an “HMM” format to indicate duration: the first digit represents hours and the subsequent two digits represent minutes (e.g., “215” corresponds to 2 hours and 15 minutes), with two-digit entries exclusively indicating minutes. The fifth column specifies the Spread-F type through numerical codes manually assigned by researchers based on ionogram image characteristics: 1 for frequency Spread-F (FSF), 2 for range Spread-F (RSF), 3 for mixed Spread-F (MSF), 4 for strong range Spread-F (SSF), and 0 (“non-SF”) for all non-Spread-F cases. The remaining six columns contain non-essential data that are excluded from analysis.

Data preprocessing

Figure 1(a) displays a representative ionogram captured by the HA419 ionosonde at Hainan Station on DOY 003 (January 3, 2012) at 09:00:00, showcasing the standard data visualization format that incorporates multiple annotation layers, including the color bar (right panel), station metadata and timestamp (header), and supplementary annotations (footer). While these contextual elements provide critical reference points for manual analysis by ionospheric scientists, our machine learning framework is specifically designed to classify Spread-F events exclusively from the visual patterns within the ionograms, mimicking human-like task performance. Consequently, the auxiliary information is not relevant for constructing the ionogram dataset intended for deep learning applications.

To address this, we removed the surrounding annotations and retained only the graphical content of the ionogram bounded by the coordinate axes (demarcated by the red box in Fig. 1(a)). Specifically, we cropped the original ionogram from 700 × 600 pixels to a focused 494 × 451, preserving the complete graphical area while eliminating irrelevant annotations. Since most classification networks require the input size to be a square matrix, we further resized the image to 448 × 448 pixels, rather than the commonly used 224 × 224. This resizing operation minimizes changes in image dimensions to preserve maximum spatial resolution as well as maintain critical morphological details necessary for accurate Spread-F pattern recognition.

The data preprocessing pipeline’s second stage involves processing the manually annotated text files (named in “YYYYSF” format, which records all spread-F events that occurred in that year, including their time intervals and types) and synchronizing them with the preprocessed ionogram images. This synchronization requires careful temporal alignment between two distinct timestamp formats: the ionograms maintain the original ionosonde output’s “YYYYMMDDhhmmss” naming convention, while the manual annotations utilize the more compact DOY (day-of-year) dating system. This crucial matching process ensures accurate correspondence between each preprocessed ionogram and its expert-annotated Spread-F classification label while preserving the temporal integrity of the entire dataset.

The process of parsing the manually-labeled text files can be outlined as follows.

Through the systematic implementation of this classification pipeline across the 15-year observation period (2002–2016), we generated the categorized ionogram distribution shown in Fig. 2. There are five groups of histograms corresponding to the FSF, RSF, MSF, SSF, and non-SF categories, as indicated by the labels. For each group, the lighter-colored bars represent the sample counts before Expert Validation (to be detailed later), while the darker bars indicate the validated counts. The lighter segments at the top of the bars denote the number of ionograms in the 2016 test set for the respective category. As shown, the number of non-SF samples (referenced to the right y-axis) is substantially larger than that of the four SF subtypes (referenced to the left y-axis), revealing a pronounced class imbalance that necessitates compensatory data augmentation strategies to ensure robust model training. This imbalance reflects both the natural rarity of Spread-F events and potential observational limitations, while the clear category-wise quantification makes data augmentation for minority classes a necessity.

Data augmentation

Data augmentation is a crucial technique in developing machine learning models, especially for image classification tasks. Its primary purpose is to enhance both the diversity and volume of the training dataset, thereby improving the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. Without proper data augmentation, class imbalance within the dataset can lead to biased models that perform well in the majority classes while significantly underperforming in minority ones. By artificially expanding the dataset through various transformations, data augmentation helps mitigate overfitting, enhances robustness, and ensures a more balanced learning process, ultimately leading to improved model performance across all categories.

The ionograms in our study, generated by the ionosonde’s 0–17 MHz frequency sweep (Fig. 1(a)), encode critical physical information through their frequency (x-axis) to virtual height (y-axis) relationships. These trace patterns could reflect ionospheric electron density profiles, meaning any augmentation must strictly preserve this fundamental frequency-height correlation. Commonly used image augmentation methods (rotation, cropping, stretching) would catastrophically distort the physically meaningful trace morphology, destroying the altitude-dependent plasma signatures essential for scientific interpretation. This leads to the need for specialized augmentation techniques to maintain the ionogram’s geophysical validity while expanding dataset diversity.

Our 15-year analysis of Hainan station ionograms revealed two characteristic noise types: discrete vertical point anomalies and localized patch distortions (blue arrows, Fig. 1(a)). To enhance dataset diversity and volume while preserving physical integrity, our method strategically injects these noise patterns randomly into ionograms from classes with smaller sample sizes. This physics-informed augmentation multiplies samples per category without altering their fundamental classification or distorting the critical frequency-height relationships essential for subsequent ionospheric analysis.

Specifically, we developed two noise morphologies (column and parallelogram) using Gaussian, Poisson, and salt-and-pepper noise models. Through parameter optimization, we selected nine distinct noise variants: Gaussian (σ² = 0.05, 0.10, 0.15), Poisson (λ = 1, 2, 4), and salt-and-pepper (density = 0.1, 0.15, 0.2).

These noise patterns were applied randomly in terms of size, location, and type to maintain augmentation diversity, ensuring that each augmented image contains at least one type of noise region. In detail, the width of column noise was randomly selected from 1 to 5 pixels, while the parallelogram noise had a base randomly ranging from 35 to 45 pixels and a height from 18 to 25 pixels. The parameter constraints for these two noise morphologies were manually determined after observing numerous ionograms. Representative examples of noise-augmented ionograms are shown in Fig. 3, while their original category labels are preserved. Specifically, ionogram (a) is FSF with salt-and-pepper noise (density = 0.2), (b) is RSF with Poisson noise (λ = 4), and (c) is MSF with Gaussian noise (σ² = 0.15); each was augmented by adding one or two column- and parallelogram-shaped noises.

To address the substantial class imbalance revealed in the initial classification results, we implemented a balanced dataset construction strategy with a target size of 20,000 ionograms per category. This threshold was strategically selected based on empirical considerations to mitigate the extreme disproportion between the RSF category (containing only 2,211 raw samples) and the “non-SF” category (with 431,001 samples). The balancing process involved two complementary approaches: (1) down-sampling of the “non-SF” category to reduce its volume, and (2) augmentation of the minority classes (FSF, MSF, SSF, and particularly RSF) using our simulated noise techniques. Through this dual approach, we successfully generated a standardized dataset comprising 100,000 ionograms equally distributed across all five categories (20,000 samples per class), while preserving the geophysical validity of all augmented samples.

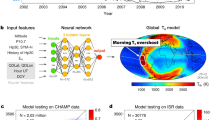

Training assistant classification models

With the preliminary ionogram dataset prepared, we adopted a standardized machine learning workflow by partitioning the data into training (80%) and validation (20%) subsets, while reserving the temporally distinct 2016 ionograms as an independent test set to evaluate model generalization. In accordance with the methodology outlined in Wang et al. (2023), we trained three distinct deep-learning models on this preliminary dataset: ResNet5042, EfficientNet43, and Vision Transformer (ViT)44. These models were carefully selected based on the previous experimental experience. The use of multiple neural networks also aims to provide as many ionogram classification methods as possible, ranging from convolutional networks to attention-based transformers.

Final ionogram dataset construction

The methodology for constructing the final ionogram dataset follows a systematic six-stage pipeline.

-

1.

Initial Classification: The raw ionograms (2002–2016) were categorized according to their original manual annotations, preserving the expert-labeled ground truth.

-

2.

Preliminary Dataset Creation: Through the first noise simulation augmentation, we generated a preliminary balanced dataset using ionograms from 2002 to 2015, with 20,000 samples per category (a total of 100,000 samples in 5 classes), mitigating the initial class imbalance. The ionograms of 2016 were used as a separate test set, which is not co-distributed with the Preliminary Dataset.

-

3.

Model Development and Selection: We trained multiple classification models using the Preliminary Dataset and selected the three models, ResNet50, EfficientNet, and Vision Transformer (ViT), which achieved the highest overall classification accuracy on the test set to serve as assistant classifiers.

-

4.

Automated Reclassification: All ionograms (2002–2016) were reprocessed through the three trained models to produce refined, machine-enhanced classification labels.

-

5.

Expert Validation: Domain specialists conducted rigorous quality control, manually verifying and correcting the AI-generated labels to ensure physical consistency and scientific validity.

-

6.

Final Dataset Assembly: Leveraging the validated classifications from 2002 to 2015, we generated an enhanced training/validation dataset via a second round of augmentation applied directly to the original ionograms, resulting in 30,000 samples per category (150,000 in total) with ensured label accuracy. The 2016 ionograms, after undergoing label correction, continued to serve as an independent test set, fully separate from the training and validation data.

Following the model-assisted re-classification and expert validation process, the updated classification distribution for the 2002–2015 ionograms showed significant refinements: 421,306 samples were confirmed as “non-SF” (previously 431,001), while Spread-F categories demonstrated adjusted counts of 13,920 FSF (originally 10,099), 8,496 RSF (from 2,211), 15,089 MSF (from 14,648), and 10,416 SSF (from 11,268). The 2016 test set exhibited similar label optimizations, with “non-SF” decreasing marginally from 43,722 to 43,671, FSF reducing to 1,709 (from 1,797), RSF increasing to 481 (from 307), MSF slightly rising to 1,833 (from 1,817), and SSF decreasing to 410 (from 461), as quantitatively illustrated in Fig. 2. This whole workflow combines automated machine learning techniques with expert domain knowledge to produce a high-quality, balanced ionogram dataset suitable for advanced space weather research applications.

One point that needs to be clarified is that in the Preliminary Dataset, we set the sample size for each category at 20,000, while in the Final Dataset, we increased this number to 30,000. This decision was primarily based on the varying degrees of class imbalance. When building the Preliminary Dataset, RSF had only 2,211 samples compared to 431,001 “non-SF” samples. Excessive data augmentation at this stage could easily lead to model overfitting. However, when building the Final Dataset, the RSF category had already increased to 8,496 samples, allowing us to safely augment its sample size to 30,000 through additional data enhancement.

Data Records

The dataset, named “HA419-IonogramSet-202505”, has been fully uploaded and is now available for open access at “https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.26826”45. It is distributed as four compressed archives.

-

1.

“2002_2015_classification.rar”: This archive contains ionograms from 2002 to 2015, with specialist-corrected labels but without data augmentation.

-

2.

“HA_80_20_uniform.rar”: This archive holds the fully augmented dataset, comprising 150,000 ionograms distributed across 5 categories.

-

3.

“2016_classification.rar”: This archive includes ionograms from the year 2016 with expert-updated labels, serving as the test set.

-

4.

“example_dataset.rar”: This archive contains five category-specific folders, each with 100 ionograms corresponding to its respective class.

Both “2002_2015_classification.rar” and “2016_classification.rar” contain five folders: “Freq,” “Mix,” “non-SF,” “Range,” and “SRange,” each corresponding to a specific ionogram category. These folders store all ionograms belonging to their respective categories. The archive file “example_dataset.rar” also contains five category-specific folders, each with 100 ionograms corresponding to its respective class. This resource is intended primarily as an illustrative reference, enabling users to understand what Spread-F is, how it appears in ionograms, and to visually compare ionograms with and without Spread-F, as well as the differences among the various Spread-F types. In “ HA_80_20_uniform.rar”, the images are divided into two folders, “train” and “val,” which also respectively contain five category-based subfolders. These structured subsets facilitate the training and validation of various custom classification models, enabling researchers to develop and evaluate their algorithms effectively.

The dataset contains PNG-format images adhering to two distinct naming conventions. The first, exemplified by “HA419_219_20100807204500.PNG,” corresponds to the raw ionogram filenames provided by the Hainan Station. In this format, “HA” denotes that the data was collected at the Hainan station, “419” represents the station number, “219” indicates the 219th day of the year, and the remaining part (“YYYYMMDDhhmmss”) specifies the exact timestamp when the ionogram was generated. The second, such as “imgs_HA419_166_2013061521200001_01.png,” is used for images generated through data augmentation. Here, “imgs” indicates that the image was created during the augmentation process, and the suffix “01” represents the type of noise randomly applied during augmentation. All other components remain consistent with the first naming convention.

Technical Validation

Upon completing the five-category low-latitude ionogram dataset compilation from Hainan Station observations, we presented a lightweight enhanced SA-ResNet50 model by integrating a spatial attention module into the standard ResNet50 architecture42. This modification improved the model’s focus on ionospheric F-layer regions. We released this model as a publicly available baseline to facilitate performance evaluation and comparative analysis in subsequent research. The ionograms in “HA_80_20_uniform.rar” were partitioned with 80% allocated to training and 20% to validation. The 2016 test set maintained inherent distributional differences from the training/validation data, as it was independently sampled rather than split from the main dataset. The images in the 2016 test set and the main dataset were obtained at different stages of different solar cycles. Treating this chronologically disjoint collection as a hold-out test set, therefore, transformed the evaluation from an in-distribution check into a genuine out-of-distribution (OOD) challenge. This segregation created more challenging out-of-distribution test conditions that could better validate the model’s generalization performance.

All our experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 Pro workstation (OS Build 26100, Version 24H2) equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (Driver 560.94). The computational framework utilized Python 3.8.13 with PyTorch 2.1.0 (CUDA 12.1 runtime), accelerated through CUDA Toolkit 11.7 (nvcc 11.7.99) and cuDNN 8.6.

Building upon this environment, we implement the canonical ResNet-50 architecture42 as our backbone network and augment its representational capacity through strategic integration of lightweight spatial attention (SA) modules46 at the terminal points of Stage 3 (conv4_x) and Stage 4 (conv5_x). Each SA module generates a spatial re-weighting mask by concurrently processing channel-wise average-pooled and max-pooled feature maps through a 7 × 7 convolutional layer with sigmoid activation, followed by element-wise multiplication with the residual output. This design maintains critical ResNet optimization properties while selectively boosting discriminative region awareness through spatial recalibration.

Our hybrid SA-ResNet50 was optimized via momentum Stochastic Gradient Descent (β = 0.9) with CrossEntropyLoss serving as the objective function. The training comprised 100 epochs using an optimizez.lr_scheduler. OneCycleLR (max_lr = 3 × 10−4, pct_start = 0.1) for adaptive learning rate adjustment. Regularization was controlled via L₂ penalty (λ = 0.001) on network parameters, effectively balancing model complexity against generalization performance.

After model training, inference was conducted on the 2016 test set using the trained weights. Model performance was subsequently evaluated by constructing a confusion matrix, as shown in Table 1, to quantify discrepancies between predicted class labels and ground-truth annotations. Based on the confusion matrix, the overall accuracy (OA) of our baseline model was calculated to be 96.82%, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.8187, both significantly exceeding the results reported by Wang et al.40. The calculation of OA and the kappa coefficient can refer to Zhao et al.47.

Additionally, we also calculated the precision, recall, overall accuracy, and F1 score for each category, including an aggregated evaluation of all Spread-F types as a whole, “SF” category. This meant the values of the green background in Table 1 could be summed up and regarded as one value. This value indicates the number of ionograms whose classification results are detected as Spread-F. In other words, the accuracy for the “SF” type reflects the model’s ability to correctly identify the occurrence of Spread-F events, without necessarily specifying the exact subtype of Spread-F. All calculated results are presented in Table 2. As shown, the precision values for FSF and RSF are still unsatisfactory, while the values for MSF and SSF are barely acceptable. In comparison, only the precision and recall values for “Spread-F” and “non-SF” are commendable.

Analysis of Tables 1, 2 reveals that the current baseline model achieves satisfactory performance in detecting Spread-F (SF) events. In other words, a data-driven, learning-based method demonstrates reliable capability in determining the occurrence of SF. However, its performance in fine-grained classification of SF subtypes based on ionograms remains suboptimal and requires further improvement. Severe class imbalance makes purely vision-based ionogram classification a highly challenging research problem, necessitating additional efforts. This challenge, in fact, serves as a key motivation for our open-source release of this dataset and its accompanying code. We hope to encourage broader contributions from the research community to develop enhanced classification methods, thereby alleviating the laborious and time-consuming task of manual ionogram interpretation.

Although the baseline model exhibits limited accuracy and recall in subtype classification, we argue that this work holds significant value for three key reasons. First, to our knowledge, this dataset represents the largest and most temporally extensive labeled ionogram corpus publicly available, built upon years of expert-annotated data from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Second, all ionogram labels in the Final Dataset underwent rigorous review and correction by domain experts following AI-assisted pre-classification, ensuring high annotation reliability. Finally, we deliberately rcn independent test set (rather than splitting subsets from the 2002–2015 data) to strictly enforce distributional divergence between training/validation and test sets. This design can evaluate model generalizability more rigorously.

Usage Notes (optional)

The three uploaded archives provide two primary methods for researchers to utilize the dataset. The first method involves directly using the pre-classified images in “HA_80_20_uniform.rar” to train custom classifiers, then performing inference on ionograms in “2016_classification.rar” and comparing results against both ground truth labels and the baseline model’s performance. The second method enables full reproduction of our benchmark pipeline by first processing the 2002–2015 ionograms in “2002_2015_classification.rar” through two sequential scripts: “ sample_random_noise_uniform.py” reduces the “non-SF” category to 30,000 samples, while using the technique we specified to increase the FSF/RSF/MSF/SSF category to 30,000 samples. And “split_data.py” creates training/validation splits, after which researchers can train custom models and evaluate them against the test set using the same comparison framework. Both approaches maintain dataset consistency while allowing flexible experimental designs.

Data availability

All ionograms analyzed in this study were generated by the digital ionosonde deployed at the Hainan station of the Chinese Meridian Project. The dataset, HA419-IonogramSet-202505, has been publicly released and is available for download from the Science Data Bank at https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.26826.

Code availability

All codes for this project were implemented in Python 3.8.13 using the PyTorch framework (version 2.1.0). The complete codes have been made publicly available at: “https://github.com/CCaijh/Hainan_classification”. The repository includes:

• Training and inference scripts for the baseline model;

• Classification results of the baseline model on the 2016 test set (saved in TXT format);

• All necessary Python scripts for reproducing our experiments.

• The shuffle sequence we used during the training process

To ensure bit-wise reproducibility, we fixed every random generator to the same value (seed = 2026) before dataset shuffling and model initialization. In addition, we recorded the exact per-epoch shuffle permutations generated by the DataLoader; these index sequences (“.\train_order.txt”) are released with our code repository, enabling readers to replay the identical mini-batch order used in all reported runs. However, it is worth noting that differences in the operating system version or language settings may affect the generation of random numbers, potentially leading to final training outcomes that differ from those we have provided.

It should be noted that the pretrained weights provided were derived from ionogram data collected by the digital ionosonde at the Hainan station. Previous statistical studies19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 have demonstrated that, at low geomagnetic latitudes (±20°), the occurrence types of Spread-F and their corresponding ionogram characteristics are highly consistent across Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Consequently, the pretrained weights are applicable to regions within ±20° geomagnetic latitude, corresponding to the Equatorial Ionization Anomaly zone. For Spread-F classification tasks based on ionograms collected at stations outside this latitude range, we recommend retraining or fine-tuning the shared model weights on a reasonably sized set of manually labeled ionograms, following a workflow similar to that proposed in this study.

References

Fejer, B. G., Scherliess, L. & De Paula, E. R. Effects of the vertical plasma drift velocity on the generation and evolution of equatorial spread F. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 104, 19859–19869 (1999).

Abdu, M. A. Day-to-day and short-term variabilities in the equatorial plasma bubble/spread F irregularity seeding and development. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 6 (2019).

Olugbon, B. et al. Daytime Equatorial Spread F-Like Irregularities Detected by HF Doppler Receiver and Digisonde. Space Weather 19, e2020SW002676 (2021).

Piggott, W. R. & Rawer, K. URSI Handbook of Ionogram Interpretation and Reduction. 68–73 (1972).

Yasyukevich, Y. et al. Small-Scale Ionospheric Irregularities of Auroral Origin at Mid-latitudes during the 22 June 2015 Magnetic Storm and Their Effect on GPS Positioning. Remote Sens. 12, 1579 (2020).

Booker, H. G. & Wells, H. W. Scattering of radio waves by the F-region of the ionosphere. Terr. Magn. Atmospheric Electr. 43, 249–256 (1938).

Carter, B. A. et al. An analysis of the quiet time day‐to‐day variability in the formation of postsunset equatorial plasma bubbles in the Southeast Asian region. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 119, 3206–3223 (2014).

Klenzing, J. et al. A system science perspective of the drivers of equatorial plasma bubbles. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 9 (2023).

Mendillo, M., Meriwether, J. & Biondi, M. Testing the thermospheric neutral wind suppression mechanism for day‐to‐day variability of equatorial spread. F. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 106, 3655–3663 (2001).

S Saito & T Maruyama. Large-Scale Zonal Structure of the Equatorial Ionosphere and Equatorial Spread F Occur- rence. J. Natl. Inst. Inf. Commun. Technol. 56, Nos. 1-4 (Special Issue: Space Weather Forecast), 267–276 (2009).

Maruyama, T. & Matuura, N. Longitudinal variability of annual changes in activity of equatorial spread F and plasma bubbles. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 89, 10903–10912 (1984).

Basu, S. et al. Day‐to‐day variability of the equatorial ionization anomaly and scintillations at dusk observed by GUVI and modeling by SAMI3. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 114 (2009).

Tsunoda, R. T. On the enigma of day-to-day variability in equatorial spread F. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32 (2005).

Takahashi, H. et al. Multi-instrument study of longitudinal wave structures for plasma bubble seeding in the equatorial ionosphere. Earth Planet. Phys. 5, 1–10 (2021).

Kelley, M. C., Larsen, M. F., LaHoz, C. & McClure, J. P. Gravity wave initiation of equatorial spread F: A case study. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 86, 9087–9100 (1981).

Abdu, M. A. et al. Gravity wave initiation of equatorial spread F/plasma bubble irregularities based on observational data from the SpreadFEx campaign. Ann. Geophys. 27, 2607–2622 (2009).

Abdu, M. A. Electrodynamics of ionospheric weather over low latitudes. Geosci. Lett. 3 (2016).

Chandra, H. & Rastogi, R. G. Spread-F at magnetic equatorial station Thumba. Ann Geophys 28, 37–44 (1972).

Shi, J. K. et al. Relationship between strong range spread F and ionospheric scintillations observed in Hainan from 2003 to 2007. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 116 (2011).

Wang, G. J., Shi, J. K., Wang, X. & Shang, S. P. Seasonal variation of spread-F observed in Hainan. Adv. Space Res. 41, 639–644 (2008).

Wang, G. J. et al. The statistical properties of spread F observed at Hainan station during the declining period of the 23rd solar cycle. Ann. Geophys. 28, 1263–1271 (2010).

Jiang, C. et al. Ionosonde observations of daytime spread F at low latitudes. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 121 (2016).

Alfonsi, L. et al. Comparative analysis of spread‐F signature and GPS scintillation occurrences at Tucumán, Argentina. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 118, 4483–4502 (2013).

González, G. D. L. Spread-F characteristics over Tucumán near the southern anomaly crest in South America during the descending phase of solar cycle 24. Adv. Space Res. 69, 1281–1300 (2022).

Sahai, Y. et al. Generation of large-scale equatorial F-region plasma depletions during lowrange spread-F season. Ann. Geophys. 22, 15–23 (2004).

Wang, Z. et al. Strong range SF observed in low latitude ionosphere over acsension IS in Atlantic ocean. in 2017 Progress In Electromagnetics Research Symposium - Spring (PIERS) 1879–1883, https://doi.org/10.1109/piers.2017.8262056 (IEEE, St. Petersburg, 2017).

Wang, Z., Shi, J. K., Torkar, K., Wang, G. J. & Wang, X. Correlation between ionospheric strong range spread F and scintillations observed in Vanimo station. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 119, 8578–8585 (2014).

Ye, H. et al. Multi-Instrumental Observations of Midlatitude Plasma Irregularities over Eastern Asia during a Moderate Magnetic Storm on 16 July 2003. Remote Sens. 15, 1160 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. Longitudinal differences in the statistical characteristics of ionospheric spread-F occurrences at midlatitude in Eastern Asia. Earth Planets Space 71, 47 (2019).

Xie, H. et al. Statistical Study on the Occurrences of Postsunset Ionospheric E, Valley, and F Region Irregularities and Their Correlations Over Low-Latitude Sanya. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 123, 9873–9880 (2018).

Cueva, R. Y. C., De Paula, E. R. & Kherani, A. E. Statistical analysis of radar observed F region irregularities from three longitudinal sectors. Ann. Geophys. 31, 2137–2146 (2013).

Thammavongsy, P., Phakphisut, W. & Supnithi, P. A Preliminary Neural Network Model for Range Spread-F Events at Chumphon Station, Thailand. in 2018 18th International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies (ISCIT) 395–398, https://doi.org/10.1109/iscit.2018.8588013 (IEEE, Bangkok, 2018).

Thammavongsy, P., Supnithi, P., Phakphisut, W., Hozumi, K. & Tsugawa, T. Spread-F prediction model for the equatorial Chumphon station, Thailand. Adv. Space Res. 65, 152–162 (2020).

Feng, J., Wu, A. & Zheng, W. S. Shape-erased feature learning for visible-infrared person re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 22752–22761 (2023).

Bhaneja, P., Klenzing, J., Pacheco, E. E., Earle, G. D. & Bullett, T. W. Statistical analysis of low latitude spread F at the American, Atlantic, and Pacific sectors using digisonde observations. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 11 (2024).

Lan, T., Zhang, Y., Jiang, C., Yang, G. & Zhao, Z. Automatic identification of Spread F using decision trees. J. Atmospheric Sol.-Terr. Phys. 179, 389–395 (2018).

Lan, T., Hu, H., Jiang, C., Yang, G. & Zhao, Z. A comparative study of decision tree, random forest, and convolutional neural network for spread-F identification. Adv. Space Res. 65, 2052–2061 (2020).

Luwanga, C., Fang, T., Chandran, A. & Lee, Y. Automatic Spread‐F Detection Using Deep Learning. Radio Sci. 57 (2022).

Venkateswara Rao, T., Sridhar, M. & Venkata Ratnam, D. Auto-detection of sporadic E and spread F events from the digital ionograms. Adv. Space Res. 70, 1142–1152 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Automatic Detection and Classification of Spread‐F From Ionosonde at Hainan With Image‐Based Deep Learning Method. Space Weather 21 (2023).

Benchawattananon, P. et al. Automatic classification of spread‐F types in ionogram images using support vector machine and convolutional neural network. Earth Planets Space 76, 56 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2016.90 (IEEE, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks.

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Gao, P. et al. HA419-IonogramSet-202505. Science Data Bank (ScienceDB) https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.26826.

CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. in Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3–19, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018).

Zhao, X. et al. The Prediction of Day‐to‐Day Occurrence of Low Latitude Ionospheric Strong Scintillation Using Gradient Boosting Algorithm. Space Weather 19 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Public Computing Cloud of CUC and the following grants: Project of Stable Support for Youth Team in Basic Research Field, CAS (YSBR-018); Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2023000116); The Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Grant No. XDA0470301; Specialized Research Fund for State Key Laboratories; Pandeng Program of National Space Science Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences; the High-quality and Cutting-edge Disciplines Construction Project for Universities in Beijing (Internet Information, Communication University of China); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. Mostly, we would like to acknowledge the use of data from the Chinese Meridian Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: P.G., Z.W., Data Collection: M.Z.H., X.W., K.D., Data curation: Q.Z., Q.Q., Z.W., G.W., Y.Z.H., J.S., Data proofreading: Q.Z., M.Z.H., Z.W., G.W., Y.Z.H., Software: P.G., J.C., Q.Q., C.Q., B.W., Experiments: Q.Z., J.C., Z.W., G.W., Visualization: Q.Z., C.Q., B.W., Manuscript writing: P.G., J.C., Z.W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, P., Zhu, Q., Cai, J. et al. A Deep Learning-Enabled Ionogram Dataset for Detection and Classification of Low-latitude Spread-F Phenomena. Sci Data 13, 181 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06493-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06493-5