Abstract

Malus baccata ‘Jackii’ has been observed to exhibit multiple disease resistances, thus rendering it a promising source for breeding new disease-resistant apple cultivars. Here, we present the first haplotype-resolved genome assembly and annotation of this genotype, achieved by integrating PacBio HiFi sequencing, Hi-C, and mRNA sequencing data with a range of bioinformatic tools and databases. The genome assembly comprises 17 pseudochromosomes with total scaffold lengths of 654.6 Mb and 637.5 Mb for the two haplotypes, respectively. Both haplotypes have scaffold N50 values exceeding 30 Mb, with 42,441 and 46,507 predicted genes, of which 99.9% were successfully annotated. The high quality of this genome is supported by BUSCO analysis values exceeding 97.5% for both haplotypes. This comprehensive dataset is well suited for a wide range of future genomic analyses and is anticipated to benefit apple breeding, particularly in the context of enhancing disease resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) is among the most popular and important fruits in the world. Different closely related species of apple (Malus spp.) can hybridize easily, and the domesticated apple of today contains genomic contributions from e.g. Malus sieversii, Malus sylvestris, Malus orientalis and Malus baccata1. M. baccata is native to Asia and is used for breeding cultivars and rootstocks due to its distinct cold hardiness and disease resistance2. Breeding of new apple varieties is a complex process that takes several years3. Sequencing the genomes of apple genotypes provides insights into genetic diversity, evolutionary history, and genotype-phenotype relationships. The availability of whole genome sequences facilitates the development of marker-assisted selection (MAS), which aids breeding by enabling more efficient and targeted selection strategies. Recently, many genomes from various apple cultivars and individual accessions of different Malus species have been sequenced and published4, including that of M. baccata2. However, until now, no genome sequence has been available for M. baccata ‘Jackii’, an ornamental genotype collected in 1905 by J. G. Jack in Seoul5, which exhibits resistance to several fungal diseases such as apple scab (Venturia inaequalis)6, powdery mildew (Podosphaera leucotricha)7 and apple blotch (Diplocarpon coronariae)8. In addition, M. baccata ‘Jackii’ is resistant to fire blight9,10, caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Erwinia amylovora, which is one of the most destructive bacterial diseases affecting the genus Malus11. Breeding resistant apple cultivars is a promising and desirable strategy against fire blight and would require pyramiding the different resistance gene (R-gene) candidates due to the fact that resistance is strain-dependent, with some R-gene donors already overcome by virulent strains of E. amylovora11,12. The first fire blight R-gene to be isolated and functionally characterized using a transgenic approach was FB_Mr5, which underlies the resistance QTL region at the top of chromosome 3 of Malus × robusta 513,14. FB_Mr5 encodes a CC-NBS-LRR resistance protein that interacts with the cysteine protease AvrRpt2Ea from E. amylovora, demonstrating a gene-for-gene relationship9,13,14,15,16. Moreover, sequence analysis of avrRpt2Ea from various E. amylovora strains, along with inoculation experiments using avrRpt2Ea knock-out mutants, revealed that FB_Mr5-mediated resistance in Malus × robusta 5 is lost when inoculated with knockout mutants and strains carrying a cysteine-to-serine substitution at amino acid position 156 in the bacterial effector avrRpt2Ea. Furthermore, it was shown that fire blight resistance in M. baccata ‘Jackii’ likely functions in a similar manner to that of Malus × robusta 59,16. Additionally, a closely related homologue of FB_Mr5 was identified in M. baccata ‘Jackii’17. However, as it has been demonstrated that even a single amino acid substitution in specific regions of FB_Mr5 can have a significant impact and trigger autoactivity18, it is important to know the exact sequences of resistance genes and whether there are other candidate genes at an R-gene locus that show a very high sequence similarity. In this study, we generated a high-quality, haplotype-resolved genome assembly and annotation of M. baccata ‘Jackii’ by combining PacBio HiFi sequencing with Hi-C and mRNA sequencing. Tunable genotyping-by-sequencing (tGBS)19 data of an F1 biparental population derived from an ‘Idared’ × M. baccata ‘Jackii’ cross were generated, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified by mapping the sequences to the newly assembled genome. By additionally mapping the sequences of the tGBS analysis to the HFTH1 reference genome, chromosome names were assigned based on the HFTH1 assembly20. The genome assembly and annotation presented here for this multi-resistant genotype are of significant value and can be utilised directly for various resistance analyses and other applications.

Methods

Sampling, DNA and RNA extraction

Leaves from M. baccata ‘Jackii’ were collected at the Fruit Genebank of the Julius Kühn-Institut (JKI) in Dresden-Pillnitz, Germany. The QIAGEN Genomic-tip 20/G kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was used for DNA extraction, while the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) was employed for RNA extraction, with both procedures conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols.

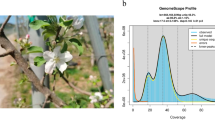

Genome size estimation using Illumina sequencing

Genomic DNA from diploid M. baccata ‘Jackii’ was sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with a paired-end read length of 150 bp and a 350 bp sequencing library. Subsequently, the reads were quality-filtered (polyG tails trimmed, minimum length ≥ 100 bp, average read quality ≥ Q20, homopolymer filter ≤ 10% consecutive identical bases, ≤50% of bases with Q < 10). After filtering, a total of 80.14 GB of sequencing data was obtained, corresponding to an estimated sequencing depth of ~135.19 × . The GC content was 37.22%, with Q20 exceeding 97.85% and Q30 surpassing 93.87%. Genome analysis was conducted using the Jellyfish 2.1.421 and GenomeScope 2.022 software. The k-mer distribution map with k = 19 was generated, the haploid genome size of M. baccata was estimated to be 592.8 Mb and the heterozygosity rate was calculated to be ~1.57% (Fig. 1). The repeat sequence content was estimated at ~52.78%.

Haplotype-resolved genome assembly with PacBio and Hi-C

DNA from M. baccata ‘Jackii’ was used for PacBio HiFi sequencing on the PacBio Revio platform (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) following the standard protocol. The DNA molecules were sequenced in zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) over multiple cycles, and repeated subreads were combined to generate highly accurate, self-corrected HiFi reads. In total, 6,149,970 HiFi reads were produced, yielding 101.3 Gb of sequence data. The average HiFi read length was 16,479 bp, with an N50 of 16,808 bp, and the longest HiFi read measured 61,744 bp.

In addition, an in situ Hi-C experiment was conducted23. To preserve DNA-DNA interactions and maintain the 3D genome structure, cross-linking was performed with formaldehyde and subsequently DNA was digested with the HindIII restriction enzyme generating sticky ends that were filled in with biotin-labeled nucleotides. Blunt-end ligation was performed to form circular structures. After reversing the cross-linking, the DNA was purified and sheared into fragments between 300–700 bp. Biotinylated junctions were isolated using streptavidin beads, and purified fragments were utilised for library preparation and sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 PE150 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). This process generated 689.2 M read pairs, corresponding to 206.3 Gb of sequence data, with an average GC content of 39.54%, a Q20 value of 97.98%, and a Q30 value of 94.70%. The Hi-C data were processed using HiC-Pro v2.10.024, and the paired-end reads were aligned using BWA (v0.7.10-r789; mode: aln; default settings)25 to the preliminary assemblies of haplotype 1 and haplotype 2. These preliminary haplotype-resolved assemblies were generated using only HiFi reads with Hifiasm (v0.19.9-r616)26 through three main steps: haplotype-aware error correction, which preserves heterozygous sites to maintain phasing accuracy, phased string-graph construction, and contig generation. Of the total 1,378.4 M Hi-C reads, 1,174.7 M and 1,175.4 M reads were mapped to the preliminary assemblies of haplotype 1 and 2, respectively. Among these, 538.1 M and 538.9 M reads were uniquely mapped, resulting in 196.9 M (36.59%) and 196.6 M (36.48%) valid interaction pairs for haplotype 1 and 2, respectively. The preliminary assembly was segmented into 50-kb fragments and scaffolded into haplotype-resolved pseudochromosomes using Hi-C data with LACHESIS27. The following optimised parameters were applied: CLUSTER_MIN_RE_SITES = 118, CLUSTER_MAX_LINK_DENSITY = 2, ORDER_MIN_N_RES_IN_TRUNK = 75 (haplotype 1) / 15 (haplotype 2), and ORDER_MIN_N_RES_IN_SHREDS = 87 (haplotype 1) / 15 (haplotype 2). In total, 98.1% and 99.0% of the Hi-C-derived sequences were anchored for haplotypes 1 and 2, respectively, with 97.3% and 98.8% confirmed in correct order and orientation. A summary of the Hi-C-based haplotype-resolved genome assembly is presented in Table 1.

The assembled genome sequence was cut into 300 kb bins, and the signal intensity between corresponding bins was visualized as a heatmap in Fig. 2. The signal intensity was stronger within the 17 chromosome groups than between them, indicating a high-quality genome assembly.

Transcriptome sequencing and genome annotation

The assembled genome was then used for genome annotation, with transposable element prediction performed using the following programs and databases: RepeatModeler2 v2.0.128, RECON v1.0.829, RepeatScout v1.0.630, LTR_retriever v2.831, LTRharvest v1.5.932, LTR_FINDER v1.133, RepeatMasker v4.1.034, Repbase v19.0635, REXdb v3.036 and Dfam v3.237. Tandem repeats were predicted using the Microsatellite identification tool (MISA v2.1)38 and the Tandem Repeat Finder (TRF, v409)39. The results of the aforementioned analyses are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

The coding gene prediction was performed using three complementary approaches: ab initio, homology-based, and transcriptome-based methods (with and without reference genomes). Ab initio coding gene prediction was carried out using Augustus v2.440 and SNAP (2006-07-28)41. Homology-based predictions were performed with GeMoMa v1.742, and for transcriptome-based predictions, mRNA sequencing was performed on Illumina Novaseq. 6000 platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with a paired-end read length of 150 bp. This yielded a total of 40.3 M reads, corresponding to 12.1 Gb. The Q30 and Q20 values were 94.57% and 98.01%, respectively, and the GC content was 48.16%. Transcripts were predicted using HISAT v2.0.443 and StringTie v1.2.344 with different reference genomes20,45,46,47. Coding genes were then identified using GeneMarkS-T v5.148. Additionally, transcripts were assembled without the use of a reference genome with Trinity v2.1149, and coding genes were predicted with PASA v2.0.250. Finally, the genes predicted by the different methods were integrated using EVM v1.1.151 and finalized by PASA v2.0.250. The total number of coding genes predicted for haplotype 1 and 2 was 42,441 and 46,507, respectively. Detailed results are presented in Tables 4 and 5 and in Fig. 3.

Venn diagram of integrated predicted coding genes. (a) Haplotype 1. (b) Haplotype 2. Created with Venny81.

Non-coding RNA prediction was conducted with tRNAscan-SE v1.3.152 for tRNA, with barrnap v0.953 based on Rfam v12.054 for rRNA, with miRBase55 for miRNA, and with Infernal 1.156 based on Rfam v12.054 for snoRNA and snRNA. The results are summarised in Table 6.

Homologous gene sequences without a complete gene locus were identified using GenBlastA v1.0.457 and GeneWise v2.4.158 was used to detect premature stop codons and frameshift mutations, resulting in the identification of 228 and 308 pseudogenes, respectively (Table 7).

The predicted coding genes were functionally annotated using multiple databases, including GenBank Non-Redundant (NR, 20200921), eggNOG 5.059, Gene Ontology (GO, 20200615)60,61, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, 20191220)62, SWISS-PROT and TrEMBL (202005)63, Pfam v3364 and eukaryotic orthologous groups (KOG, 20110125). Overall, more than 99.9% of coding genes were successfully annotated. The statistics on gene function annotation are presented in Table 8.

In the final step, InterProScan (5.34-73.0)65 was utilised for the prediction of motifs and domains. A total of 1,876 motifs and 45,003 domains were predicted in haplotype 1, and 1,820 motifs and 44,973 domains in haplotype 2.

Chromosome assignment according to HFTH1

DNA of 184 F1 individuals from the cross ‘Idared’ × M. baccata ‘Jackii’, including the parental genotypes, was analysed using tGBS19 by Data2Bio (Ames, IA, USA). The restriction enzyme Bsp1286I was used and sequencing was carried out on an Illumina HiSeq X instrument (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Polymorphic sites were first identified, and in a second step, final SNP calling was performed. In the initial step, individual sequence reads were scanned for low-quality regions (PHRED score ≤15), and quality-trimmed sequence reads were aligned to the genome sequences of haplotypes 1 and 2 of M. baccata ‘Jackii’ reported here using GSNAP66. Only confidently mapped reads with ≤2 mismatches per 36 bp and no more than 4 bases as tails per 75 bp that aligned to a single location were used for SNP identification, based on the following criteria: for homozygous SNPs, the most common allele had to be supported by at least 5 unique reads and 80% of all aligned reads. For heterozygous SNPs, each of the two most common alleles had to be supported by at least 5 unique reads and at least 30% of all aligned reads. For both homozygous and heterozygous SNPs, polymorphisms in the first and last 3 bp of each quality-trimmed read were ignored, and a PHRED base quality value of 20 (≤1% error rate) was set as the threshold for each polymorphic base. In the second step, SNPs were classified for tGBS genotyping as follows: a SNP was classified as homozygous if ≥5 reads supported the major allele and ≥90% of all reads at that site matched, and heterozygous if ≥2 reads supported each of two alleles, both alleles individually made up >20%, and their combined reads were ≥5, covering ≥90% of all reads at that site. SNPs were then filtered based on a minimum calling rate of 50%, the allele number was set to 2, the number of genotypes ≥2, the minor allele frequency ≥10%, and the heterozygosity rate range between 0% and (2 × Frequencyallele1 × Frequencyallele2 + 20%). In a final step, imputation was used on chromosome-based SNPs that lacked a sufficient number of reads to make genotype calls using Beagle v5.467 with 50 phasing iterations and default parameters. A total of 321,733 and 319,620 SNPs for haplotypes 1 and 2 were identified, with each site genotyped in at least 50% of the samples. SNP sequences from the tGBS data were then mapped to the HFTH1 genome sequence20 using BWA-MEM268 on the JKI Galaxy Server (Galaxy v2.2.1 + galaxy1)69 and the data presented in this study were assigned and oriented according to the HFTH1 reference20. A Circos plot70 illustrating key genomic features and alignments between the two haplotypes is shown in Fig. 4.

Circos plot of the Malus baccata ‘Jackii’ haplotype-resolved genome assembly. (a) Chromosome names and lengths in Mb. (b) Frequency of tandem repeats in 50 kb windows. (c) Frequency of transposable elements in 50 kb windows. (d) Frequency of genes in 50 kb windows. (e) Sequences from the tGBS analysis of haplotype 1 mapped onto haplotype 2. kb: kilobase, Mb: million base pairs, tGBS: tunable genotyping-by-sequencing.

Data Records

The raw data and assembled sequences and annotations can be accessed from the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the BioProject accession number PRJEB8994271 and study number ERP172974. The SNPs and their corresponding sequence data, as well as the adjusted genome sequences (Mbj_HT1/Mbj_HT2.fasta), gene and peptide sequences (cds.fasta and pep.fasta), and annotation data (final tandem repeats, TE final, EVM.final.gene, domains and motifs) are available from Figshare72.

Technical Validation

BUSCO analysis

To assess the completeness of the genome assembly, a BUSCO analysis with BUSCO v4.073 was performed using the Embryophyta database containing 1,614 core genes. The results, presented in Table 9, demonstrate the high integrity of the haplotype-resolved genome assembly, with 97.58% and 97.52% of the core genes identified in haplotype 1 and 2, respectively.

Mapping back Illumina short and PacBio HiFi reads

In addition, Illumina short reads were mapped back to the haplotype-resolved assemblies using BWA (v0.7.10-r789; mode: aln; default settings)25 to assess completeness and read distribution. The mapping ratio exceeded 99.3% for both haplotypes, and approximately 83.5% of reads were properly mapped, i.e., paired clean reads that mapped to the same reference sequence within a defined distance threshold (Table 10), confirming the high assembly integrity. Sequencing depth and coverage analysis revealed an average depth of 114–116 × , with >99.3% of the genome covered at ≥20× (Table 11). These metrics indicate uniform sequence representation and negligible missing regions, demonstrating that the assembled genomes are highly complete and suitable for downstream analyses.

PacBio HiFi reads were also mapped back to the haplotype assemblies using Minimap274, yielding similar results, with mapping ratios above 99.7% for both haplotypes, average sequencing depths of 154–155×, and ≥20× genome coverage for >99.1% of the genome.

k-mer-based evaluation with Merqury

The quality and completeness of the haplotype assemblies were further assessed using a k-mer-based approach with Merqury75. HiFi raw reads were first adapter-trimmed using Cutadapt76 (Galaxy v5.1 + galaxy069), and the trimmed reads were then processed with Meryl75 (Galaxy v1.3 + galaxy669) to generate 31-mer counts. The individual k-mer databases were merged using the union-sum method to create a comprehensive reference k-mer database representing the full diploid sequence content. Merqury75 (Galaxy v1.3 + galaxy469) was then used to evaluate how many of the raw-read k-mers were present in each assembly, enabling an independent assessment of completeness for haplotype 1, haplotype 2, and the combined diploid assembly. The Merqury analysis demonstrated a high level of completeness for both haplotype assemblies: 77.2% of the expected 578.5 M k-mers were recovered in haplotype 1 and 76.9% in haplotype 2. The combined diploid assembly recovered 99.5% of the k-mers, demonstrating that the two haplotypes together capture nearly the entire diploid genome with high completeness.

LTR Assembly Index

The LTR Assembly Index (LAI)77 was calculated separately for each haplotype to assess assembly continuity within long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposon-rich regions. For each haplotype, the assembly was first indexed using the GenomeTools suffixerator (GenomeTools v1.6.2)78. LTR retrotransposon candidates were then identified with LTRharvest32 (GenomeTools v1.6.2)78 and subsequently curated and filtered using LTR_retriever v2.9.031. Haplotype 1 yielded a genome-wide LAI of LAI₁ = 11.4, while haplotype 2 showed a comparable value of LAI₂ = 12.6. With LAI values ≥ 10, both assemblies meet the criteria for reference-quality genomes77, indicating that LTR retrotransposons are reconstructed with high continuity across both haplotypes.

Application of the genome assembly in fire blight resistance mapping

To demonstrate the usability and quality of the genome assembly for downstream applications, we applied it in an association mapping approach to identify the fire blight resistance locus of M. baccata ‘Jackii’, which had been previously proposed17. A total of 119 progenies derived from an ‘Idared’ × M. baccata ‘Jackii’ cross, as well as both parental genotypes, were grafted onto rootstock MM111, and up to five replicates per genotype were phenotyped for fire blight incidence i.e., length of shoot tip necrosis after artificial inoculation using E. amylovora strain Ea222, as described in Peil et al.14. Mean percent lesion length (PLL) was calculated for each F1 genotype by dividing the length of necrotic shoot by the total shoot length and averaging data from experiments conducted in 2024 and 2025. To identify potential associations between SNPs and fire blight incidence, each SNP from the aforementioned tGBS analysis with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.05 was analysed using the following procedure: genotypes were divided into two groups according to the observed allele. Using ‘Idared’ as a reference for the susceptible allele, phenotypic values of the two groups were used for a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test performed in R v4.4.279. The genome-wide significance threshold was determined using Bonferroni correction as -log10(0.01/number of SNPs tested). A Manhattan plot was generated using the ggplot2 package80 and it showed a significant association of SNP markers at the top of chromosome 3 with the fire blight phenotypic data of the F1 progeny, shown for haplotype 2 in Fig. 5. Haplotype 1 produced a comparable plot (not shown). The sequence of the FB_Mr5 homolog in M. baccata ‘Jackii’ (GenBank accession KT013244.117) was found to be 100% identical over 4,164 bp to a region at the top of chromosome 3 of haplotype 2 between positions 598,337 and 602,501 bp, and this homolog is only 43,365 bp distant from the SNP marker with the highest -log₁₀(p) value and the strongest association with fire blight resistance. This supports the accuracy of the haplotype-resolved genome assembly, the correctness of chromosome assignment and orientation, as FB_Mr5 has been described to be located on the distal part of chromosome 314, and the reliability and usability of the genomic data presented here for further analyses.

PLL in the F1 biparental (‘Idared’ × M. baccata ‘Jackii’) population after artificial fire blight inoculation. (a) Mean necrosis (%) across 2024 and 2025. (b) Correlation of necrosis between years across F1 genotypes. (c) Manhattan plot of the genome-wide association for mean PLL in the F1 population with newly generated SNP markers of haplotype 2. The dashed line indicates the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold. Mb: million base pairs, PLL: percent lesion length, SNP: single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Code availability

A custom R script was used to perform association mapping and is provided as supplementary information.

References

Cornille, A., Giraud, T., Smulders, M. J. M., Roldán-Ruiz, I. & Gladieux, P. The domestication and evolutionary ecology of apples. Trends Genet. 30, 57–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2013.10.002 (2014).

Chen, X. et al. Sequencing of a Wild Apple (Malus baccata) Genome Unravels the Differences Between Cultivated and Wild Apple Species Regarding Disease Resistance and Cold Tolerance. G3: Genes Genomes Genet. 9, 2051–2060, https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.119.400245 (2019).

Flachowsky, H. et al. Application of a high-speed breeding technology to apple (Malus × domestica) based on transgenic early flowering plants and marker-assisted selection. New Phytol. 192, 364–377, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03813.x (2011).

Genome Database for Rosaceae. https://www.rosaceae.org/species/malus/all (2025).

Fiala, J.L. Flowering crabapples: The genus Malus (Timber Press, Portland, 1994).

Gygax, M., Gianfranceschi, L., Liebhard, R., Kellerhals, M. & Patocchi, A. Molecular markers linked to the apple scab resistance gene Vbj derived from Malus baccata jackii. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 1702–1709, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-004-1803-9 (2004).

Dunemann, F. & Schuster, M. Genetic characterization and mapping of the major powdery mildew resistance gene Plbj from Malus baccata jackii. Acta Hortic. 814, 791–798, https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.814.134 (2009).

Wöhner, T., Emeriewen, O. F. & Höfer, M. Evidence of apple blotch resistance in wild apple germplasm (Malus spp.) accessions. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 159, 441–448, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-020-02156-w (2021).

Vogt, I. et al. A. Gene-for-gene relationship in the host-pathogen system Malus × robusta 5-Erwinia amylovora. New Phytol. 197, 1262–1275, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12094 (2013).

Wöhner, T. et al. Inoculation of Malus genotypes with a set of Erwinia amylovora strains indicates a gene‐for‐gene relationship between the effector gene eop1 and both Malus floribunda 821 and Malus ‘Evereste. Plant Pathol. 67, 938–947, https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12784 (2017).

Peil, A., Emeriewen, O. F., Khan, A., Kostick, S. & Malnoy, M. Status of fire blight resistance breeding in Malus. J. Plant Pathol. 103, 3–12, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42161-020-00581-8 (2021).

Emeriewen, O. F., Wöhner, T., Flachowsky, H. & Peil, A. Malus Hosts-Erwinia amylovora Interactions: Strain Pathogenicity and Resistance Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 551, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00551 (2019).

Fahrentrapp, J. et al. A candidate gene for fire blight resistance in Malus × robusta 5 is coding for a CC–NBS–LRR. Tree Genet. Genomes 9, 237–251, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-012-0550-3 (2013).

Peil, A. et al. Strong evidence for a fire blight resistance gene of Malus robusta located on linkage group 3. Plant Breed. 126, 470–475, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01408.x (2007).

Broggini, G. A. L. et al. Engineering fire blight resistance into the apple cultivar ‘Gala’ using the FB_MR5 CC-NBS-LRR resistance gene of Malus × robusta 5. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12, 728–733, https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12177 (2014).

Wöhner, T. W. et al. QTL mapping of fire blight resistance in Malus ×robusta 5 after inoculation with different strains of Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Breed. 34, 217–230, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-014-0031-5 (2014).

Wöhner, T. et al. Homologs of the FB_MR5 fire blight resistance gene of Malus ×robusta 5 are present in other Malus wild species accessions. Tree Genet. Genomes 12, 2, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-015-0962-y (2016).

Kim, H., Kim, J., Kim, M., Park, J. T. & Sohn, K. H. Comparative analysis on natural variants of fire blight resistance protein FB_MR5 indicates distinct effector recognition mechanisms. Mol. Cells 47, 100094, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mocell.2024.100094 (2024).

Ott, A., Schnable, J. C., Yeh, C.-T., Wang, K.-S. & Schnable, P. S. tGBS® genotyping-by-sequencing enables reliable genotyping of heterozygous loci. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, e178, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx853 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. A high-quality apple genome assembly reveals the association of a retrotransposon and red fruit colour. Nat. Commun. 10, 1494, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09518-x (2019).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27, 764–770, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 11, 1432, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3 (2020).

Rao, S. S. P. et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021 (2014).

Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biol. 16, 259, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0831-x (2015).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021).

Burton, J. N. et al. Chromosome-scale scaffolding of de novo genome assemblies based on chromatin interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 1119–1125, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2727 (2013).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 9451–9457, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Bao, Z. & Eddy, S. R. Automated de novo identification of repeat sequence families in sequenced genomes. Genome Res. 12, 1269–1276, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.88502 (2002).

Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics 21, i351–i358, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018 (2005).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A Highly Accurate and Sensitive Program for Identification of Long Terminal Repeat Retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.01310 (2018).

Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinform. 9, 18, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-18 (2008).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–W268, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current Protoc. Bioinform. 25, 4.10.1–4.10.14, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009).

Jurka, J. et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 462–467, https://doi.org/10.1159/000084979 (2005).

Neumann, P., Novák, P., Hoštáková, N. & Macas, J. Systematic survey of plant LTR-retrotransposons elucidates phylogenetic relationships of their polyprotein domains and provides a reference for element classification. Mob. DNA 10, 1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13100-018-0144-1 (2019).

Wheeler, T. J. et al. Dfam: a database of repetitive DNA based on profile hidden Markov models. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D70–D82, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1265 (2013).

Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U. & Mascher, M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 2583–2585, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198 (2017).

Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.2.573 (1999).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24, 637–644, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn013 (2008).

Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinform. 5, 59, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-5-59 (2004).

Keilwagen, J. et al. Using intron position conservation for homology-based gene prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e89, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw092 (2016).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3317 (2015).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015).

Daccord, N. et al. High-quality de novo assembly of the apple genome and methylome dynamics of early fruit development. Nat. Genet. 49, 1099–1106, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3886 (2017).

Lamesch, P. et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1202–D1210, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr1090 (2012).

Li, Z. et al. Chromosome-scale reference genome provides insights into the genetic origin and grafting-mediated stress tolerance of Malus prunifolia. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 1015–1017, https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13817 (2022).

Tang, S., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. Identification of protein coding regions in RNA transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e78, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv227 (2015).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. A. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 (2011).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–5666, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg770 (2003).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008).

Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.5.955 (1997).

Loman, T. A Novel Method for Predicting Ribosomal RNA Genes in Prokaryotic Genomes. MSc thesis, Lund University (2017).

Griffiths-Jones, S. et al. A. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D121–D124, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki081 (2005).

Griffiths-Jones, S., Grocock, R. J., van Dongen, S., Bateman, A. & Enright, A. J. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D140–D144, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkj112 (2006).

Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 29, 2933–2935, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013).

She, R., Chu, J. S.-C., Wang, K., Pei, J. & Chen, N. GenBlastA: enabling BLAST to identify homologous gene sequences. Genome Res. 19, 143–149, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.082081.108 (2009).

Birney, E., Clamp, M. & Durbin, R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1865504 (2004).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D309–D314, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1085 (2019).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29, https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

The Gene Ontology Consortium. et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 224, iyad031, https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyad031 (2023).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1070 (2016).

Boeckmann, B. et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 365–370, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg095 (2003).

Finn, R. D. et al. Pfam: clans, web tools and services. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D247–D251, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkj149 (2006).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 (2014).

Wu, T. D. & Nacu, S. Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics 26, 873–881, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq057 (2010).

Browning, B. L., Zhou, Y. & Browning, S. R. A One-Penny Imputed Genome from Next-Generation Reference Panels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 338–348, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.015 (2018).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1303.3997 (2013).

Afgan, E. et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W3–W10, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw343 (2016).

Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.092759.109 (2009).

ENA. European Nucleotide Archive. https://identifiers.org/ena.embl:PRJEB89942 (2025).

Pfeifer, M. et al. Associated dataset of Malus baccata ‘Jackii’ genome sequence. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30664886.v3 (2025).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 (2018).

Rhie, A., Walenz, B. P., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 21, 245, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9 (2020).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12, https://doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200 (2011).

Ou, S., Chen, J. & Jiang, N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e126, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky730 (2018).

Gremme, G., Steinbiss, S. & Kurtz, S. GenomeTools: A Comprehensive Software Library for Efficient Processing of Structured Genome Annotations. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 10, 645–656, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCBB.2013.68 (2013).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2023).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer-Verlag New York, 2016).

Oliveros, J.C. Venny: An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn’s diagrams. https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html (2007-2015).

Acknowledgements

Parts of this work were supported by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Regional Identity by decision of the German Bundestag (funding reference number: 281D108X21).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception: Henryk Flachowsky, Andreas Peil and Thomas Wöhner. Strategy and design: Matthias Pfeifer, Ofere Francis Emeriewen and Thomas Wöhner. Analyses and writing: Matthias Pfeifer and Thomas Wöhner. Plant material: Monika Höfer and Andreas Peil. Fire blight phenotyping: Holger Zetzsche. Association mapping and analysis: Matthias Pfeifer, Ofere Francis Emeriewen, Jens Keilwagen, Fang-Shiang Lim and Thomas Wöhner. Data curation and upload: Jens Keilwagen and Fang-Shiang Lim. Funding: Thomas Wöhner. Supervision: Henryk Flachowsky and Thomas Wöhner. Revision: All authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pfeifer, M., Emeriewen, O.F., Flachowsky, H. et al. High-quality haplotype-resolved genome assembly and annotation of Malus baccata ‘Jackii’. Sci Data 13, 14 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06504-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06504-5