Abstract

We present a unique dataset of historical tropical tree phenology observations at two sites from different bioclimatic regions across the Congo Basin. We cover both the Atlantic Mayombe forest and the tropical forest in the central Congo Basin. To our knowledge this is the complete extant historical (1937–1957) phenology data across the Congo basin. The data contains ~10 million observations of 876 species, across 6339 individuals, and phenology metrics including leaf, flowering, and fruiting phenology. The data were recovered through expert transcription and validated community science based crowdsourcing. These data may provide a reference baseline and key information on how tree species are responding to a changing climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tropical tree phenology affects the timing of critical ecosystem processes such as carbon, water and nutrient cycles1. As such, changes in tropical forest leaf phenology actively contribute to the modification of climate, from the local to global scale2,3. Tropical forests therefore play a significant role in the Earth’s carbon budget and strongly influence the regional and global climate4,5,6. In addition, the phenology of flowering and fruiting of trees connects to organisms across many trophic levels7 and is critical for the survival of pollinator and frugivore species. Frugivore species, in turn, are key in the propagation of tree species and have a profound impact on regeneration dynamics and potential of forests to recover after (anthropogenic) disturbances7.

For the central African ‘moist’ forest belt we have little process-based understanding of the forest’s phenological patterns. Previous studies have shown that species and even individuals seem to display a wide range of phenological behaviour and are potentially responding to different endogenous and exogenous cues8,9. A more complete characterization of the periodicity, synchrony and drivers of leaf phenology at the individual and species level is important to understand tropical tree phenology at the ecosystem scale, and to predict how stand-level phenology may alter with a changing climate10.

Given diverse species level responses it has been argued that using contemporary remote sensing solutions alone is insufficient for assessing tropical tree phenology11. This is specifically important for the Congo Basin, which stands out pantropically for being drier than the Amazon Basin or South-East Asia12, and exhibiting a bimodal rather than a unimodal seasonality11,13. Satellite analyses have suggested that the tropical evergreen state is not sustained year-round if mean annual precipitation is roughly below 2000 mm12.

At the same time, consistent and long-term historical observations of tropical tree phenology, across the Congo Basin or the tropics remain limited10,14. Despite these data limitations, it is increasingly important to understand how variations in climate have affected ecosystem functioning in the past to predict with more certainty how ecosystems will respond in the future. Few long-term high frequency phenology measurements are made of tropical tree species14,15 due to the challenges posed by such large species diversity16 and the sustained monitoring work involved over many years to decades needed to document patterns and processes within a rainforest ecosystem. Even less (baseline) data traces back to periods preceding large climate change induced disturbances experienced by these forests today17. It has been argued that the complexity of such forests necessitates ground-based long-term monitoring with a high coverage of species in tropical forests to understand both historical and current phenological behaviour and how phenology scales to a landscape level10,15.

Here, we present a unique dataset of historical tree phenology observations, using a consistent methodology, from the late 1930s to the late 1950s, across two sites in the Congo Basin. It covers both the Atlantic Mayombe forest and the tropical forest in the central Congo basin. To our knowledge, this is the complete extant historical phenology data across the Congo basin. The data contain ~10 million weekly to bi-weekly observations of 876 species, across 6339 individuals and various phenology metrics, including leaf senescence and turnover, flowering, and fruiting phenology. The data were recovered through expert transcription and validated community science based crowdsourcing and is augmented with stand level species distribution data where available. These data may provide key information on how sensitive seasonal dynamics in tree species and their co-dependent species, across trophic levels, are responding to a changing climate.

Methods

Study sites

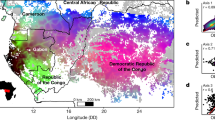

The Luki and Yangambi Research Stations are located in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC, see Fig. 1) and were historically part of an agriculture- and forestry-based research infrastructure project. The Luki and Yangambi research facilities were established in the 1920’s, and in 1933 integrated in the ‘Institut National pour l’Étude Agronomique du Congo’ (INEAC). The INEAC created and developed a network of 30–40 stations (depending on the time frame chosen), each with its own focus. Researchers in Yangambi for example focused on applied research and fundamental research in botany, climatology, tropical agronomy, forestry, and other disciplines. At the Yangambi and Luki research sites, moist semi-deciduous forest in both the central Congo Basin and the coastal Mayombe forests, respectively, continue to be studied. At both centres, the study of the forest flora, the establishment of scientific collections (exsiccata, seeds, seedlings, wood, pathogens and diseases), the observation of the rhythmic phenomena (phenology) such as leaf development, flowering and fruiting and the study of forest stands was central. The independence of the Congo in 1960 brought an abrupt end to the intensive research efforts and the accessibility of the accumulated expertise of the INEAC. Independence substantially impacted the operation and research of the institute in the following years and the institute was renamed to INERA in 1962. Today, INERA continues research at the agricultural centers across the DRC, where an impressive library with archived documents are stored in Yangambi with some duplicates in the State Archives of Belgium. At both sites, reserves were created in the 1940’s, and in the 1970’s they were declared protected Man and Biosphere reserves (MaB) by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

The Yangambi MaB forest reserve is situated ~100 km downstream of the city of Kisangani in the central Congo Basin. Currently, the Yangambi forest reserve covers an area of 2,350 km2 just north of the Congo River with an average elevation of ~459 masl. The historical research facilities (including the herbarium, arboretum, climatological station) are located in the southwestern part of the reserve (N00°48′; E24°29′). The site currently also hosts the first eddy covariance tower in the Congo Basin (CongoFlux) and provides critical contemporary data on ecosystem fluxes18 and field based observations. Based on historical vegetation descriptions19, different types of vegetation are found in Yangambi. The most extensive part of the reserve consists of semi-deciduous old-growth forest. The floristic composition is highly diverse, although a high abundance of Scorodophloeus zenkeri Harms is generally found. Other species that are often abundant include Cynometra hankei Harms, Dialium corbisieri Staner, Greenwayodendron suaveolens (Engl. & Diels) Verdc., Anonidium mannii (Oliv.) Engl. & Diels, Strombosiopsis tetrandra Engl., Prioria oxyphylla (Harms) Breteler, Celtis mildbraedii Engl., Prioria balsamifera (Vermoesen) Breteler and Pericopsis elata (Harms) Meeuwen. Localized patches of the monodominant evergreen Gilbertiodendron dewevrei (De Wild) J.Léonard and of the evergreen dominant Brachystegia laurentii (De Wild) Louis J.Léonard are also present. In the valleys of the Congo River and tributaries, other vegetation types are found. The Yangambi reserve also contains sites with different levels of human intervention and secondary forests20. The central Congo Basin rainforests experience a weak seasonal climate with a bimodal periodicity of wet and dry seasons21 generated by the movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone. Yangambi has the Af climate according to the Köppen classification with two slightly marked dry seasons, an average annual precipitation of 1837 mm, and mean annual temperature of 25.1 °C22. The reserve has two dry seasons with monthly precipitation lower than 150 mm, during December - February and June – July. Average temperatures are high and constant throughout the year with a minimum of ~24.2 °C in July and a maximum of ~25.5 °C in March. In this reserve, an increase in temperatures and temperature extremes has been observed since the 1960s. Since 2000, there has also been a notable change in rainfall patterns, with a shift towards a more seasonal climate characterised by longer dry periods and shorter, more intense rainy periods. This climate change is also having an impact on the composition and functioning of forest ecosystems and biodiversity in the Congo Basin22. The geology of the region consists of unconsolidated aeolian sedimentary sandy material of Pleistocene age, giving way to xanthic ferralsols23,24.

The Luki forest reserve is located 30 km north of Boma. The forest reserve covers ~ 330 km2 and spans a hilly landscape with altitudes varying from 150 to 500 masl over an extent of latitudes 5°30′-5°45′S, and longitudes 13°7′-13°45′E. The hilly terrain exposes the soil to heavy erosion and limits the formation of deep soils. Soils are ferralitic, acidic and of poor quality. Average annual temperature ~24.6 °C. Rainfall is seasonal with a pronounced dry season with only 60 mm of rain from June to September and an annual average of ~1180 mm. The hilly terrain in proximity of the ocean causes orographic cloud formation and keeps the relative air humidity high (>80%). A high air humidity prevents extreme water stress in the vegetation despite the pronounced dry season. For a detailed site description, including species composition, we refer to Couralet et al.25.

Phenological observations and forest inventories in the Congo Basin at Luki and Yangambi were made as part of wider forestry research efforts initiated by the INEAC to describe the phenology and stand dynamics of these two different forests from the late 1930s to the late 1950s11,26. Overall, some fifteen thousand (15 000) trees were regularly observed for years up to decades27 within the context of forestry research, of which less than half were observed for phenology research. We report here on phenological observations made on ~6000 monitored trees, including some lianas28, between the late 1930’s and late 1950’s across almost a thousand species, of which almost 500 trees can still be found growing to the present day.

Data recovery

Observation protocols and records

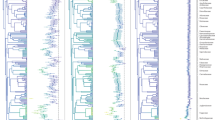

Historical data were recovered from a phenological study carried out between 1937 and 1956 in the Yangambi MaB reserve28. A total of 476 handwritten tables (Fig. 2) from the INERA (Institut National pour l’Etude et la Recherche Agronomique) herbarium at the Yangambi Research Station were digitized for archiving purposes. The sampling protocol we present here is based on the protocols found in the State Archives of Belgium28 or deduced from the raw data itself. Observations of tree phenology were made on a weekly schedule (approximately Monday to Saturday, with an interval of four weeks to a month), grouping trees by a fixed geographically constrained itinerary to limit travel time. Observational routes were followed, along which trees were flagged with bright blazes, signs (Fig. 3) or metal ID plaques (at Luki, see below), and observed by locally trained personnel familiar with the vegetation. At Yangambi mostly white paint on the trees, and a sign next to the tree was used. From the recovered historical descriptions we determined that every observer would observe roughly ~132 trees per day along their phenological route. Observations included the timing of flowering, fruit development and dispersion (fruit drop), leaf senescence (or turnover), and disturbances (tree death) which were written down in field notebooks and summarized in large tables (Fig. 4). Canopy leaf senescence was defined as a distinct period during which leaves fall and trees remain bare, while canopy turnover was defined as a period during which leaf-fall comes in peaks with concomitant flushes of new leaves (Fig. 4c). The observed trees are representative of the wide Yangambi region from the islands in the Congo river to the plateau to the north of Yangambi. The protocol at the Luki forest reserve followed the same observation schedule as applied in Yangambi. Here, 3750 woody plants were monitored from January 1948 until December 1957. The Luki dataset was manually transcribed by experts from the handwritten notebooks, similar to those used for the summary tables at Yangambi (see Fig. 4c). Due to data quality issues data was resampled to three observations per month. This data has been previously described and used by Couralet et al.26.

A summarizing data sheet of the historical phenological observations recovered at the Yangambi archives, at the time located at the herbarium library. Observations of 10 individual trees are shown (rows), identified with the tree’s ID number, species name, family name and local name (inset a). A year of observations is shown (inset b). Each consecutive year is marked by thick grid-lines. Vertical fine grid-lines represent one month, with half a year indicated with a vertical medium thick line. For each individual tree four phenophases are observed, indicated in French from top to bottom floraison (fl., flowering), fructification (fr., fruiting), dissémination (diss., seed dissemination) and hivernation (hiv., leaf senescence). Actual observations for each phenophase are indicated with pencil marks along the respective horizontal grid-lines. These pencil marks are drawn at a resolution of a quarter of a month, representing on average 7.2 days. The pencil markings of leaf senescence show a distinction of simple horizontal lines representing periods of leaf fall, while the tree remains bare, or cross-hatched lines during periods of leaf-fall and concomitant flushes of new leaves. The end of observation periods are often indicated with a cross, often combined with a reason, for example here the observation of the second individual stops during the second year due to mortality through tree fall (‘tombé par le vent’). Full summarizing data sheets cover ten individuals and ten years, with observations of individuals at times continuing on multiple sheets (a and b records). Note the data loss at the bottom due to rodents or insect damage on the summarizing table.

Cross referenced summary table of the row header (a) and content (b) with the original field notebooks containing the observations (c). In this sheet observations for February (Fevrier) describe “14 - 2 feuilles tombées d’autres au dessus”, or “14 - 2 fallen leaves with some on top”. The next week notes: “24 - 2 feuilles tombées au dessus rien et les jeunes feuilles au dessus”, which reads “24 - 2 fallen leaves, on top nothing and young leaves on top”. This confirms that crosshatched lines are leaf turnover events of semi-deciduous trees.

Transcription

The nature of the notation used on the summarizing data sheets (Fig. 2), using fine hand-drawn pencil lines overlapping fine table grid lines, made it impossible to process these images automatically. The Luki data was transcribed by experts, and previously described in literature29.

For the transcription of the Yangambi data we enlisted participants in the Jungle Rhythms community science project (https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/khufkens/jungle-rhythms). Participants were asked to annotate both the outline of the yearly table sections (if fully visible) and to annotate the observational features within the section. Each yearly section was presented to ten participants to improve accuracy of the annotations during post-processing.

The outline of each yearly section (six coordinates; i.e. the start, middle and end at top and bottom of each section) provided the general orientation of the section within the image, allowing the annotations to be translated into true data compensating for skewness and warping in the image using simple geometry. The weeks in which certain phenological events occur are calculated, using basic geometry of projecting lines onto an idealized grid, and the entire record for each individual tree is compiled. Median values (majority vote across ten community science annotations) were used to delineate each phenology feature, i.e. the extent of continuous phenological events. The Yangambi data record was not free of damage due to paper decomposition, in particular on creased edges, as well as rodent or insect infestation. Years which could not be clearly outlined (with six intersection points, Figs. 2, 5) were not transcribed, and are omitted from the data record (see usage notes).

Example of a completed data annotation made through the community science project Jungle Rhythms. Volunteers were presented with sections of yearly observations outlined by the bold black lines. The edges delineating the year were marked using six coordinates represented by the red polygon (i.e. the start, middle and end at top and bottom of each section). Phenological observations were marked using line segments (black lines with blue dots). Each yearly section was presented to 10 independent participants. Median values for coordinates and line segments were used to determine the final annotation. Lines were reprojected using an idealized location, i.e. the underlying inferred grid.

Ancillary data, species identification and data harmonization

To support further analysis we transcribed supporting stand level species distribution data at Yangambi from Pierlot (1966, pages 264–299, plots 20–22). This includes sampling plot data with respect to species composition and basal area as diameter at breast height (DBH, as circumference at 1.5 m) in incremental steps of 20 cm from >30 cm onward across three forest transects. Tree circumferences were converted to basal area per hectare (ha) per species.

Species names were consolidated across all datasets and were verified by the authors using the African Plant database (http://africanplantdatabase.ch/), through world flora online (https://www.worldfloraonline.org/). For the phenological data, additional cross references with the Meise Botanic Garden collection (https://www.botanicalcollections.be/) were made, since most of the ‘observed trees’ were sampled and herbarium vouchers are available in the Meise herbarium, thus a retroactive quality check on identification was possible. If uncertainty existed on the species identification of an individual (for example by unclear hand-writing or data loss through time), this individual was marked in the dataset quality assurance (qa) field (‘species_qa’, see below). All observation data was harmonized to a 365 day-of-year (DOY) scale by mapping a year with 36 or 48 observations, for Luki and Yangambi respectively, to a consistent 365 days (e.g. an observation at week one in Yangambi would correspond to DOY 7).

Data Records

The complete recovered phenological dataset for both Luki and Yangambi covers observations between 1937 and 1957 of 6339 individual trees, and is available on Zenodo30 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16789580). The Yangambi site represents 2396 individual trees and 15269 site years, ~3.8 million individual observations, covering 826 species. The Luki site represents 3943 individual trees, 42586 site-years and ~6.8 million individual observations covering fewer (155) species with higher replicate individuals. Where possible, exact coordinates of trees are provided, however this does not guarantee that the tree is currently alive. When no exact coordinates are known, e.g. all of the Yangambi data, we used the coordinates of the Luki and Yangambi MaB reserve headquarters. A separate data field ‘coord_type’ is used to mark site and individual (tree) based coordinates (see Table 1, Fig. 6).

The phenology data is provided as a single serialized and compressed (.tar.gz) CSV flat file, and a binary compressed ‘R’ serialized RDS file, describing all phenological phases and their timing using the format described in Table 1. The data is provided as a long format with a row representing a single observation. Fully accepted species names are marked as “accepted” in the ‘species_qa’ field of the datasets, unknown species (due to inconsistent species names) are marked as “unknown”, species which have issues with respect to their naming are marked “unresolved”. Data users can filter based upon the status of species names.

In addition to the phenology data itself, life-history notes are included in a separate file (Table 2). These life history notes include observations made at the end, or occasionally during, a full phenology record of a tree. These data did not correspond to the binary, presence absence, data of the five indicated phenophases. These notes were either transcribed in full for the Luki site, or extracted from hashtag data in the community science forums for Yangambi. We note that for Yangambi the hashtag data was not part of a formal workflow and lacks quality control (multiple views per yearly section). The stand level inventory data by Pierlot31 includes data on the species, circumference (from 30 cm onward, in 20 cm increments), and overall species count per plot (Table 3). The data was transcribed and is provided as a CSV flat file.

Technical Validation

Quality control and validation of the data produced through citizen science was performed using an independent validation dataset made by the authors for ~2% of the data. Data was chosen to overlap with ongoing research questions and was therefore unbalanced (non-random) across species or phenophase occurrences. All phenophases were directly transcribed into data indicating the exact weeks of the observation. We used the F-score32, or the harmonic mean of precision and recall, to assess the accuracy between the citizen science recovered data and expert transcription (Table 4). An F1 score of 1.0 indicates a perfect precision and recall. Across all phenophases we find an F1 score of 0.8 ± 0.19 and accuracy of 0.98 ± 0.001. However, the average values are negatively influenced by smaller sample sizes of leaf dormancy and turnover in the unbalanced validation dataset. As the protocol for transcription was the same for all phenophases in a yearly section (Fig. 2a) it seems unlikely that differences between phenophases are due to consistent errors in the community science transcriptions.

At Yangambi, given the lack of the full protocol, it is hard to know if the data presented is the full scope of all work ever conducted. We know that the emphasis on species changed over time when observations were transferred from the botanical division (Division Botanique) to the forestry department (Division Foresterie), which retained mostly commercial species toward the end of the observation period. Many trees with observations starting in 1937 were cut for wood biological studies and received a wood biology database (Tw) number of the Royal Museum for Central Africa (https://www.africamuseum.be/). These changes over time through anthropogenic or natural causes are noted by both the non-sequential nature of trees in the weekly planning (Fig. 2) and the recovered life history notes. However, we do acknowledge that, as far as we know, we transcribed all available archived summary tables. Assessing the full coverage of the data would require the re-evaluation of all long-form handwritten notebooks (Fig. 4).

Unlike studies using a similar protocol at the Luki MaB reserve, no remaining metal tags or exact phenology observation routes could be found in Yangambi. Yet, descriptions of the locations suggest trees covered the wide Yangambi region (see literature by Capon28, and additional meta-data). From literature, i.e. Capon, we identified nine key areas, mainly (1) Parc Isalowe (‘Parc Forestier’), (2) along the river Isalowe, (3) around the building of the forestry division, (4) at the phyto-technical department (current abandoned buildings of the IFA), (5) near experimental sites, (6) along the river Lusambilla, (7) along roads to Yangambi from Kisangani, Isangi or NGasi (‘Arbres éloignées’ or far removed trees) (8) on islands of the Congo river, and (9) in front of the Yangambi reserve (Tofende, Lomondje, Tutuku, Esali). This wide distribution has a considerable importance with respect to phenology as it mediates both soil properties and water availability during the dry season. In an early study based on the Yangambi data by Capon28 these geographic differences were already noted. For example, Lannea welwitschii fruits appeared continuously on the islands in the Congo river, while showing a far shorter cycle in other locations. Observations of fruiting were limited to those species which drop fruit. Capon28 acknowledges that observations near water or fruits desirable by humans or animals (in large quantities) might be biased as well. Similarly, they further noticed that spotting flowers on larger trees took considerable practice by observers as illustrated by historical communications to INEAC management complaining about the tedious nature of these observations. Given the wide range of locations and differences in soil and soil water conditions this might influence analysis. Where exact coordinates are missing the reported coordinates in the dataset are those of the current INERA headquarters. Users should be mindful of these limitations.

Data missingness, as in the absence of certain months or years, should be interpreted as physically unavailable data if the time series continues throughout. Missing observations can be caused by the physical destruction of the tables where the records were folded and cracked, damage from rodents, to year-on-year changes in observation schedules due to world historical or local events (e.g. World War II) or shifts in institutional interests. Years with all values set to zero (0) did not record any phenological events. Poorly annotated species data in the tables leads to unknown species information. We encourage users to use the “species_qa” flag to filter out “unknown” or “unresolved” species from the dataset as they see fit. Given these limitations we encourage users to use Yangambi phenology statistics in seasonal or yearly aggregate when possible, or cross validate these values with the provided images and or additional (local) species information to remediate these usage issues. In absence of a clear marking of the tree’s death it is hard to establish where phenological records end. We recommend considering the extent of any positive phenophase values to indicate continuous observations throughout or the last year with any phenophase values as the final year of observation. We further note that Yangambi data ran on a four week to a month schedule, while Luki was gathered on a 10-day (3 intervals) per month. Harmonization to a DOY scale allows for a direct intercomparison within the context of modelling efforts.

Data availability

The manuscript’s database is made available as a Zenodo Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16789580). The original digitized tables, and the citizen science (raw) transcriptions are available as zipped archives (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14906306 and, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14900505 respectively).

Code availability

The code and workflow used during ‘Jungle Rhythms’ community science project are available as an R project (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7650294).

References

Richardson, A. D. et al. Climate change, phenology, and phenological control of vegetation feedbacks to the climate system. Agric. For. Meteorol. 169, 156–173 (2013).

Parmesan, C. & Yohe, G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421, 37–42 (2003).

Penuelas, J. & Filella, I. PHENOLOGY: Responses to a Warming World. Science 294, 793–795 (2001).

Lewis, S. L. Tropical forests and the changing earth system. 195–210, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2005.1711 (2006).

Lewis, S. L. et al. Increasing carbon storage in intact African tropical forests. Nature 457, 1003–1006 (2009).

Pan, Y. et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 333, 988–993 (2011).

Bush, E. R. et al. Long-term collapse in fruit availability threatens Central African forest megafauna. Science 370, 1219–1222 (2020).

van Schaik, C. P., Terborgh, J. W. & Wright, S. J. The Phenology of Tropical Forests: Adaptive Significance and Consequences for Primary Consumers. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 24, 353–377 (1993).

Reich, P. B. Key canopy traits drive forest productivity. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279, 2128–2134 (2012).

Abernethy, K., Bush, E. R., Forget, P., Mendoza, I. & Morellato, L. P. C. Current issues in tropical phenology: a synthesis. Biotropica 50, 477–482 (2018).

Kearsley, E. et al. Historical tree phenology data reveal the seasonal rhythms of the Congo Basin rainforest. Plant-Environ. Interact. 5, e10136 (2024).

Guan, K. et al. Photosynthetic seasonality of global tropical forests constrained by hydroclimate. Nat. Geosci. 8, 284–289 (2015).

Liu, L. et al. Solar Radiation Triggers the Bimodal Leaf Phenology of Central African Evergreen Broadleaved Forests. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 16, e2023MS004014 (2024).

Wright, S. J. & Calderón, O. Seasonal, El Niño and longer term changes in flower and seed production in a moist tropical forest. Ecol. Lett. 9, 35–44 (2006).

Bush, E. R. et al. Fourier analysis to detect phenological cycles using long-term tropical field data and simulations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 530–540 (2017).

Davis, C. C. et al. New directions in tropical phenology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 37, 683–693 (2022).

Lewis, S. L. & Maslin, M. A. Defining the Anthropocene. Nature 519, 171–180 (2015).

Sibret, T. et al. CongoFlux – The First Eddy Covariance Flux Tower in the Congo Basin. Front. Soil Sci. 2, 883236 (2022).

Van Wambeke, A., Evrard, C.-M., Gilson, P. & Liben, L. Yangambi. (Bruxelles: INEAC, 1954).

Hufkens, K. et al. Historical Aerial Surveys Map Long-Term Changes of Forest Cover and Structure in the Central Congo Basin. Remote Sens. 12, 638 (2020).

Malhi, Y. & Wright, J. Spatial patterns and recent trends in the climate of tropical rainforest regions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 359, 311–329 (2004).

Kasongo Yakusu, E. et al. Ground-based climate data show evidence of warming and intensification of the seasonal rainfall cycle during the 1960–2020 period in Yangambi, central Congo Basin. Clim. Change 176, 142 (2023).

van Engelen, V. W. P., Verdoodt, A., Dijkshoorn, J. A. & van Ranst, E. Soil and Terrain Database of Central Africa (DR Congo, Burundi, Rwanda) Rwanda (SOTERCAF, Version 1.0). (ISRIC, Wageningen, 2006).

Batjes, N. et al. The Harmonized World Soil Database. (FAO, Rome, 2010).

Couralet, C. Community dynamics, phenology and growth of tropical trees in the rain forest reserve of Luki, Democratic Republic of Congo. (Ghent University, Ghent, 2010).

Couralet, C., Sterck, F. J., Sass-Klaassen, U., Van Acker, J. & Beeckman, H. Species-specific growth responses to climate variations in understory trees of a central african rain forest. Biotropica 42, 503–511 (2010).

Witboek/Livre Blanc II - Wetenschappelijke Bijdrage van België Tot de Ontwikkeling van Centraal-Afrika - Apport Scientifique de La Belgique Au Développement de l’Afrique Centrale, 2. Sciences Naturelles et Médicales / Natuur- En Geneeskundige Wetenschappen. (Koninklijke Academie voor Overzeese Wetenschappen, 1962).

Capon, M. Observations sur la phénologie des essences de la forêt de Yangambi. C. R. Semaine Agricole de Yangambi. in Publ. INEAC, hors série 849 (1947).

Couralet, C., Van Den Bulcke, J., Ngoma, L. M., Van Acker, J. & Beeckman, H. Phenology in functional groups of central african rainforest trees. J. Trop. For. Sci. 25, 361–374 (2013).

Hufkens, K. et al. Historical tree phenology data across contrasting sites in the Congo Basin. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.17427652 (2025).

Pierlot, R. Structure et composition de forêts denses d’Afrique Centrale, spécialement celles du Kivu. vol. XIV–4 (Koninklijke Academie voor Overzeese Wetenschappen, Brussels, Belgium, 1966).

van Rijsbergen, C. J. Information Retrieval. (Butterworths, London, 1979).

Acknowledgements

Historical phenological data recovery was supported by the Institut National pour l’Étude et la Recherche Agronomiques (INERA). Initial digitization was funded through the COBIMFO project funded by the Belgian Science Policy Office (Belspo; contract no. SD/AR/01 A). We thank all citizen scientists for their combined efforts in transcribing data in the “Jungle Rhythms” Zooniverse project. Postdoctoral funding for EK was granted by the BOF Special Research Fund, Ghent University, Belgium. KH acknowledges funding through the Belgian Science Policy office COBECORE project (BELSPO; grant BR/175/A3/COBECORE), the European Union Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action (project number 797668) and the NSF Macrosystems Biology programme (Award Numbers: EF-1065029) in supporting transcription efforts. Consolidation and post-processing of the data was funded by BlueGreen Labs (BV).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. supervised and led phenological data recovery of the Yangambi phenology data with support of E.R.K. and E.K.Y. M.K. supported the Zooniverse community science project setup. H.B., and J.V.d.B. supervised the Luki data recovery. E.K., T.D.M., P.S. and S.J. assembled critical species meta-data. E.K. and K.H. performed data analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors provided valuable insights, logistical and political support. All authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hufkens, K., Kearsley, E., Stoffelen, P. et al. Historical tree phenology data across contrasting sites in the Congo Basin. Sci Data 13, 221 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06542-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06542-z