Abstract

The U.S.-China trade friction in 2018 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 have significantly influenced China’s domestic supply chains, with their impacts varying considerably across regions and sectors. Multi-regional input-output (MRIO) models are widely used to track supply chains and analyze cross-regional spillover effects, playing a key role in understanding economic linkages and environmental impacts. However, due to data unavailability, existing MRIO tables fail to capture the impact of the U.S.-China trade friction and the COVID-19 pandemic on China’s regional supply chains. To address this data gap, we employ hybrid methods to construct Chinese MRIO tables for 2018 and 2020, covering 31 regions and 42 sectors. This dataset is consistent with our previous work on the China provincial MRIO model for the years 2012, 2015, and 2017, offering insights into how regional supply chains and economic structures adapted to the combined impacts of the trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Since China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, its regional supply chains have deeply integrated into the global value chain1,2. However, this integration is challenged by new disruptions such as geopolitical conflicts and natural disasters3,4,5. In particular, the technology blockade and tariff barriers imposed by the U.S.-China trade war since 2018 have resulted in an estimated indirect economic burden of USD 6.5 billion on China6, raising both imports and exports costs to the United States7,8, and prompting a reconfiguration of trade networks9. The lockdown and declining global demand during the COVID-19 pandemic caused China’s manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) fell sharply to a historic low of 35.7 in February 2020, exposing structural vulnerabilities in the supply chains10,11. These shocks reshaped China’s supply chain by restricting exports, diverting investments, and disturbing supply and demand dynamics3,12,13.

Amid external shocks, the challenges faced by industries vary widely across provinces and cities due to the heterogeneity of their economic characteristics14,15. In the trade war, areas with a high share of exports and exposure to targeted goods (like Guangdong and Shanghai) were impacted first, causing ripple effects across economic system. Industries with more flexible supply chains were more likely to withstand the pressure. In the 2020 pandemic, Hubei Province suffered the most severe blow from the initial outbreak. After that, other provinces experienced disruptions due to production shutdown, logistic failure and global trade halts. Nevertheless, the pandemic opened opportunities for industries like healthcare, research and digital information services. Therefore, strategies for mitigating risks and driving development must be specific to industries and satisfy each province’s conditions. We urgently need a dataset at province level to support more comprehensive research and more targeted policies.

The Multi-Regional Input-Output (MRIO) model is widely used to analyze regional economic flows, supply chain dynamics, and associated environmental impacts16,17,18,19,20,21. Numerous MRIO tables for China have been developed by institutions and individual researchers. For example, Zhang developed China’s MRIO tables for the years 1997, 2002, and 2007 using a combination of the maximum entropy model and the doubly constrained gravity model22, covering 8 regions with 17 sectors. Shi and Zhang constructed a 2002 MRIO model for China, encompassing 30 provinces and 60 sectors, employing a hybrid approach based on the Chenery-Moses framework23. Liu and colleagues improved the gravity model by incorporating spatial weights and competition coefficients to construct MRIO tables for 2007, 2010, and 201224,25,26,27. Mi proposed an MRIO table for 2012, encompassing 30 provinces and 30 sectors, using a modified gravity model28. Later, Zhao and colleagues constructed a series of MRIO tables covering 1987 to 2017 with carbon emission accounts29, which were later refined to include more detailed regional and sectoral classification. Zheng applied the maximum entropy approach to construct MRIO tables for 2012, 2015, and 2017, incorporating 31 regions and 42 sectors30. Following the approach, Wang developed the city-level MRIO table by firm ownership from 2002 to 201731. However, no existing MRIO datasets beyond 2017 are available, limiting the capacity to accurately capture the changes in China’s provincial supply structures amid the U.S.-China trade friction in 2018 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

To address this gap, we employed a hybrid approach to construct MRIO tables for 31 provinces and 42 sectors in mainland China for the years 2018 and 2020. This approach has been widely applied in the construction of MRIO tables across various countries32,33,34,35, and consistent with our previous work of the provincial MRIO tables for 2012, 2015, and 2017. Our dataset reflects changes in China’s regional economic structure influenced by U.S.-China trade friction and the COVID-19 pandemic. It is valuable for economic and environmental analysis, especially in assessing regional growth drivers and inter-regional spillover effects amid U.S.-China trade friction in 2018 and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Methods

Input data

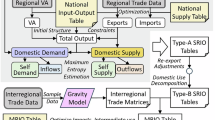

This study constructs province-level MRIO tables for China for the years 2018 and 2020 through regionalizing national IO tables published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (https://data.stats.gov.cn/ifnormal.htm?u=/files/html/quickSearch/trcc/2020_1.html&h=740). Our hybrid approach combines official survey data with simulation results31,36,37, balancing cost and data quality25,38. The provincial data used in this process include 2017 and 2020 Single-Region Input-Output (SRIO) tables39. Sectoral economic data were obtained from the statistical yearbooks published by the statistical bureaus of all 31 provinces in China. All yearbooks are publicly accessible through the respective provincial statistical bureau websites (search term: “ < Province Name > + Statistical Yearbook + < Year > ”). In addition, import-export data were sourced from China Customs (http://stats.customs.gov.cn/). All data are constrained by the national IO tables to ensure consistency. However, due to the high cost of conducting surveys, China only releases national IO tables every 2-3 years or during the economic censuses, while provincial tables published even less frequently. After 2017, only Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin have published their tables in 2020, which largely delay the construction of MRIO table. Meanwhile, sectoral data for interregional trade flows are also unavailable. To address the data limitations, we employed a cross-entropy model40,41 to generate the missing SRIO tables for each province. For inter-provincial trade, we applied a gravity model42,43 based on 2017 railway transport and electricity transmission data44 to estimate the trade matrix.

Form MRIO table

As shown in Fig. 1, the construction workflow of the MRIO table involves five stages:(1) Estimating domestic supply and demand;(2) Disaggregating domestic supply and demand;(3) Compiling provincial SRIO accounts;(4) Estimating intra-regional transaction matrices;(5) Estimating inter-regional trade matrices.

The specific construction steps of the MRIO table are as follows:

-

(1)

Estimating domestic supply and demand

First, based on the supply-demand balance principle, we estimate the supply and demand for each region and sector. Domestic supply and domestic demand include both intermediate goods and final products. From the supply perspective, the domestic supply of each region and sector should equal its total output minus foreign exports, as shown in Eq. 1:

$${{supply}}_{r}^{i}={{output}}_{r}^{i}-{{export}}_{r}^{i}$$(1)The output of sector i in province r is represented by \({{\rm{Output}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\), while \({{\rm{export}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) stands for its exports. \({{\rm{supply}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) reflects the domestic allocation of sector i’s output in province r, indicating the share that remains for domestic supply. Sectoral output data for some provinces in 2018 and 2020 is available from provincial statistical yearbooks or SRIO tables. However, some provincial yearbooks do not provide data on tertiary industry output or industrial sector value added. In these cases, we estimate the missing data by assuming identical share structures for value added and output. It means that the sectorial distribution of value added is same as the distribution of output. The assumption is used for scenarios either no sectoral value added or no sectoral output.

From the demand perspective, the domestic demand of each region and sector should equal its total demand (intermediate demand plus final demand) minus foreign imports. This data can be obtained from the provincial SRIO table, as shown in Eq. 2:

$${{demand}}_{r}^{i}={z}_{r}^{i}+{f}_{r}^{i}-{{import}}_{r}^{i}$$(2)Here, \({{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) denotes the intermediate demand for sector i in province r, while \({{\rm{f}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) represents its final demand. \({{\rm{import}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) indicates the import volume of sector i in the same province. The domestic demand of sector i in province r is defined as the total demand excluding imports (\({{\rm{demand}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\)). However, since SRIO tables are unavailable for certain provinces, the total demand cannot be directly determined. Therefore, we make the following assumptions:(1) The technical coefficients in 2018 are the same as in 2017, and the ratio of intermediate demand to total demand remains unchanged. Thus, we use the 2017 provincial SRIO table structure to estimate total demand for 2018. (2) For regions where the 2020 provincial SRIO tables are unavailable, we estimate total demand using the technical coefficients and the ratio of intermediate demand to total demand from the national IO table. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

$$\left\{\begin{array}{c}t{d}_{r}^{i\ast }=\frac{\sum _{i}{a}_{{2017}_{r}^{i}}\times {{output}}_{{2018}_{r}^{i}}}{\sum _{i}{z}_{{2017}_{r}^{i}}/{{td}}_{{2017}_{r}^{i}}}\\ t{\hat{d}}_{r}^{i}=\frac{t{d}_{r}^{i\ast }}{{\sum }_{r}t{d}_{r}^{i\ast }}\times n{d}_{{2018}^{i}}\\ {{demand}}_{r}^{i}=t{\hat{d}}_{r}^{i}-i{{mport}}_{r}^{i}\end{array}\right.$$(3)The variable \({\rm{t}}{{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}\ast }\), marked with a “*”, provides a preliminary estimation of total demand for sector i in province r. \({{\rm{a}}}_{{2017}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}}\) denotes the 2017 technical input coefficient for sector i as required by province r. The total output of sector i in province r is captured by \({{\rm{output}}}_{{2018}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}}\). Variables \({{\rm{z}}}_{{2017}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}}\) and \({{\rm{td}}}_{{2017}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}}\) refer to the intermediate and total demand for sector i in province r in 2017. \({{demand}}_{r}^{i}\) indicates the required input of sector i in province r, while \(n{d}_{{2018}^{i}}\) denotes the national demand for the same sector in 2018. Finally, \(i{{mport}}_{r}^{i}\) corresponds to the imported quantity of sector i in province r. To ensure data consistency, the total output, total demand, value added, import, and export data for each province and sector are constrained using the national IO table.

-

(2)

Detailed decomposition of domestic supply and demand

From the supply perspective, domestic supply (DS) consists of self-supply (SS) and supply to other provinces (SO). Similarly, domestic demand (DD) can be further divided into self-demand (SD) and demand from other provinces (DO), as shown in the Fig. 2.

The Cross-Entropy (CE) model can effectively adjust unknown distributions to minimize information loss while maintaining consistency with known totals45. Therefore, we use the CE model to disaggregate domestic supply and demand based on the following relationships:(1) Self-supply equals self-demand within the same province. (2) The domestic supply within a province can be further decomposed into two components: supply retained for local use (SS) and supply distributed to other provinces (SO). (3) Domestic demand within a province is the aggregate of local demand (SD) and demand from external provinces (DO). (4) The total SO from all provinces must equal the total DO from all provinces. (5) Local supply is prioritized to meet local demand, meaning that each province’s self-demand must be greater than 0. Mathematically, this can be described as:

Subject to:

\({{\rm{P}}}_{{\rm{ir}}}\) represents the allocation of supply (SS+SO) and demand (SD+DO) for sector i in province r, while \({{\rm{q}}}_{{\rm{ir}}}\) denotes the initial distribution for the same sector and province. The variables \({{\rm{s}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) and \({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\) correspond to the total domestic supply and demand aggregated across all provinces. Meanwhile, \({{\rm{s}}}_{{\rm{ir}}}\) and \({{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{ir}}}\) specify the domestic supply and domestic demand for sector i in province r.

For the 42 sectors, the initial shares of each province’s SS, SO, SD, and DO are derived from the provincial SRIO tables. The detailed calculation steps are as follows:

\({q}_{{ir}}^{{SS}},\,{q}_{{ir}}^{{SO}},{q}_{{ir}}^{{SD}}\) and \({\,q}_{{ir}}^{{DO}}\) represent the proportions of SS, SO, SD, and DO for sector i in province r, respectively. Specifically, \({{SS}}_{{ir}}\) denotes the self-supply of sector i in region r, \({{SO}}_{{ir}}\) represents the outflow, \({{SD}}_{{ir}}\) refers to the self-demand, and\(\,{{DO}}_{{ir}}\) indicates the inflow. After disaggregating the domestic supply and domestic demand by province, the sum of domestic exports from all provinces matches the total domestic imports for each sector.

Compilation of provincial SRIO accounts

Firstly, we estimate the final demand for each sector in each region using regional GDP, export and import data, external supply (supply to others), and external demand (demand from others). Secondly, the intermediate demand is obtained by multiplying the existing technical coefficient matrix with the output vector. It is important to note that although the China-U.S. trade war in 2018 brought about significant shifts in the global trade landscape, the production technologies and input-output structures inside China are unlikely to change rapidly over a short period. Accordingly, we adopt the 2017 input-output coefficients derived from SRIO tables to approximate the technological structure of each province in 2018. This is a common approach for short-term MRIO construction in data-scarce contexts to provide a reasonably accurate estimation of each province’s economic characteristics. For 2020, the technical coefficient matrices of Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai are sourced from the SRIO tables published by these provinces, while for other provinces without SRIO tables in 2020, the average technical coefficient matrix from the national IO table is used as a substitute. Then, the optimized sectoral outflows, inflows, exports, and imports for each province from the previous step are integrated with the provincial intermediate use and final demand matrices. Finally, the SRIO tables for each province are developed using a cross-entropy approach, ensuring compliance with two equilibrium conditions: (1) For each sector, the sum of intermediate demand and final demand should equal the total output minus net exports; and (2) intermediate demand is also derived by subtracting value added from total output. These relationships can be formally expressed as:

Subject to:

\({{\rm{p}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{ij}}}\) denotes the adjusted distribution obtained by updating the known prior through the cross-entropy procedure. \({\rm{e}}\) represents the natural logarithm. \({{\rm{q}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{ij}}}\), as the prior distribution, includes the intermediate demand and final demand. \({{\rm{Output}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{j}}}\) refers to the input of sector j in province r, while \({{\rm{Output}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) indicates the output of sector i in province r. \({{\rm{Net\; export}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) captures net exports of product i, calculated as total (foreign + domestic) exports minus total (foreign + domestic) imports. \({{\rm{Valve\; added}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{j}}}\) represents the value added of each sector in each region. Foreign trade data are sourced from provincial SRIO tables or China Customs.

It is important to note that when constructing the 2020 provincial SRIO tables (except for Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai), we used national technical coefficients as proxies for the technical coefficients of each province. These coefficients were then multiplied by the actual 2020 output of each region to estimate preliminary intermediate demand, which was subsequently used to calculate total demand (Z + F). Technical coefficients reflect each region’s production structure and the proportions of intermediate inputs. Provinces display pronounced heterogeneity in industrial structure and supply chain integration. Applying national technical coefficients uniformly across provinces reduces the actual and often significant technological differences among them. However, this influence is mainly confined to the technological dimension and does not eliminate regional heterogeneity. The subsequent RAS adjustment is performed to satisfy the constraints, which incorporate actual provincial data on output, demand, and trade. This helps preserve differences in economic scale and industrial structure across provinces. As a result, the final matric retain distinct provincial characteristics.

Estimation of intraregional matrix

To develop a competitive MRIO table, it is essential to transform the provincial competitive SRIO tables from Step (3) into their non-competitive counterparts. This transformation requires decomposing each province’s intermediate demand and final demand into three components: (1) demand met by local production, (2) demand fulfilled by other provinces, and (3) imports. To facilitate this disaggregation, we employ the Regional Purchase Coefficient (RPC), which estimates the proportion of total demand that is sourced locally. It is assumed that the local share of supply within both intermediate demand and final demand remains constant across each SRIO table. Therefore, local demand components in the MRIO framework are obtained by applying the RPC to the respective intermediate demand and final demand figures from the SRIO tables. The relationship is expressed mathematically as follows:

\({rp}{c}_{r}^{i}\) denotes the share of intermediate demand and final demand for sector i in region r fulfilled by local production. \({{\rm{Output}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\), \({\rm{e}}{{\rm{x}}{\rm{port}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) and \({\rm{i}}{{\rm{m}}{\rm{port}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) represent total output, foreign exports, and foreign imports, respectively. \({\rm{s}}{{\rm{o}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) denotes the outflow of sector i in province r, whereas \({\rm{d}}{{\rm{o}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) denotes the inflow of sector i in the same province. \({{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{rr}}}^{{\rm{ij}}}\) and \({\rm{f}}\) represent the amounts of intermediate demand and final demand in province r that are sourced domestically within the same province.

Estimation of interregional trade matrix

We need to estimate the share of total demand met by external regions for each province to derive the off-diagonal entries in the MRIO table for both intermediate demand and final demand.

Firstly, similar to the approach in Step (4), we introduce the Import Purchase Coefficient (IPC) to quantify the portion of each province’s intermediate and final demand supplied by other provinces. It is assumed that this interregional import ratio remains consistent across intermediate demand and final demand within each SRIO framework. Formally:

\({\rm{ip}}{{\rm{c}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) denotes the share of intermediate demand and final demand for sector i in region r fulfilled by imported products. \({{\rm{Output}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\), \({\rm{e}}{{\rm{xport}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) and \({\rm{i}}{{\rm{mport}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) represent the total output, foreign exports, and foreign imports, respectively. \({\rm{s}}{{\rm{o}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) denotes the outflow of sector i in province r, whereas \({\rm{d}}{{\rm{o}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) denotes the inflow of sector i in the same province. \({{\rm{zm}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{ij}}}\) and \({\rm{f}}{{\rm{m}}}_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) represent the amounts of intermediate demand and final demand in province r that are met by imported products, respectively.

Secondly, due to the lack of detailed interregional trade matrices for all 42 sectors, we employ a gravity model using railway transportation data for 11 categories of goods to estimate interregional trade flows across 24 sectors within the input-output framework. For non-transportable sectors (e.g., services and construction), transport costs are not considered; rather, we assume allocation is proportional to regional supply and demand. For electricity, interregional electricity transmission data from the China Electricity Power Yearbook is used to estimate related trade flows. This method and data are consistent with our previous study, thereby ensuring consistency over the time series. The general structure of the gravity model is defined as:

\({{\rm{trade}}}_{{\rm{rs}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) represents the volume of interregional trade for product i from province r to s, while \({{\rm{distance}}}_{{\rm{rs}}}\) denotes the geographic distance between the two regions, serving as a proxy for transport-related costs. \({{\rm{outflow}}}_{{\rm{ro}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) indicates the amount of product i that province r supplies to other provinces, whereas \({{\rm{inflow}}}_{{\rm{os}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) denotes the volume of product i that province s imports from other provinces. However, the initial trade matrix obtained from the above steps does not satisfy the row and column constraints for domestic exports and imports in the provincial SRIO tables. To reconcile these discrepancies, we utilize the RAS balancing method to adjust the trade matrix, thereby ensuring coherence with the supply and demand constraints of the SRIO tables.

Thirdly, based on the balanced trade matrix, we compute the share of total domestic imports supplied by each province-referred to as the regional purchase proportion (RP). By applying this proportion to each region’ s total domestic demand, we derive the volume of demand met by other provinces. Mathematically:

Here, \({{\rm{rp}}}_{{\rm{rs}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) represents the share of domestic imports of product i flowing from province r to province s, while \({{\rm{trade}}}_{{\rm{rs}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) reflects the volume of sector i’s trade from r to s. \({{\rm{zm}}}_{{\rm{s}}}^{{\rm{ij}}}\) and \({\rm{f}}{{\rm{m}}}_{{\rm{s}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) denote the intermediate and final demand for the imported products i to province s. \({{\rm{z}}}_{{\rm{rs}}}^{{\rm{ij}}}\) and \({{\rm{f}}}_{{\rm{rs}}}^{{\rm{i}}}\) represent the intermediate and final demand fulfilled by domestic imports flowing from province r to province s.

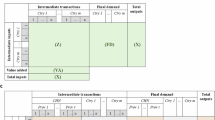

Data Records

The dataset is available at the China Emission Accounts and Datasets (CEADs, www.ceads.net) and Figshare46 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29927291). The 2018 and 2020 China MRIO tables reflect the economic linkages and industrial structure evolution among regions during the U.S.-China trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic. The structure of our China’s MRIO tables for 2018 and 2020 is shown in Fig. 3. It consists of the intermediate demand matrix (1302 × 1302), final demand matrix (1302 × 155), value-added matrix (5 × 1302), import vector (1 × 1457), export vector (1302 × 1), total output vector (1 × 1302), and total output vector (1302 × 1). Economic relationships among 31 provinces and 42 sectors in China are captured by the intermediate demand matrix. The final demand matrix comprises five categories: urban household consumption, rural household consumption, government consumption, fixed capital formation, and changes in inventories. The value-added matrix consists of four components: compensation of employees, net taxes on production, depreciation of fixed capital, and operating surplus. Imports and exports, categorized by province and sector, are captured in separate vectors. The import vector distinguishes between intermediate demand (1 × 1302) and final demand (1 × 155).

Technical Validation

MRIO table balancing

This study constructs the “Errors” column vector (1302 × 1) in the China MRIO table to reflect total output balancing errors. In all provinces, the discrepancy in total output across the 42 sectors stays within a ±5% range. The “Errors” column vector represents the difference between the total output of each sector in each province and the sum of its intermediate demand, final demand, and net exports. Figure 4 presents heatmaps of error terms across 31 provinces and 42 sectors for 2018 and 2020. Deeper red indicates a greater positive deviation of sectoral total output from the actual value, while deeper blue indicates a greater negative deviation. For example, in 2018, the largest output discrepancy was observed in Sector 4 (Mining and Processing of Metal Ores) in Province 8 (Heilongjiang), with a deviation of 1.5%. In 2020, the most significant discrepancies occurred in Sector 4 of Province 7 (Jilin) and Sector 12 (Manufacture of Chemical Products) in Province 30 (Ningxia), with deviations of 1.7% and −1.7%, respectively. These deviations primarily stem from balancing inconsistencies in the provincial input-output tables and mismatches between total inflows and outflows across provinces.

Discrepancies between MRIO and national IO table

Currently, no other institutions have published MRIO tables for China for the years 2018 and 2020. Therefore, to validate the reliability of our MRIO tables for these years, we compare them with the official national SRIO tables. The results show that, in both 2018 and 2020, the differences in domestic intermediate inputs across most sectors remain within ±10%, indicating a high degree of overall consistency between the two datasets. Only a few sectors exhibit relatively large discrepancies (see Fig. 5). Specifically, in 2018, the sectors “Extraction of petroleum and natural gas,” “Processing of petroleum, coking, and processing of nuclear fuel,” and “Production and distribution of gas” show deviations of −24%, +21%, and +25%, respectively. By contrast, in 2020, the largest discrepancy is concentrated in “Mining and processing of metal ores” (11%). These discrepancies mainly stem from the assumption that intermediate and final demand share the same import ratio when converting the competitive SRIO table into a non-competitive format. For example, in 2018, the discrepancy for the “Extraction of Petroleum and Natural Gas” sector reached −24%, primarily due to an overestimation of intermediate imports in the MRIO table—88% higher than the actual value. Since this sector is highly import-dependent, with approximately 54% of its supply sourced from abroad, the discrepancy is further amplified under the import estimation assumptions described above. Therefore, it is reasonable that sectors with high import reliance are more prone to larger discrepancies during the MRIO construction process. Access to more detailed import data-especially distinguishing between intermediate and final demand—would enhance the consistency and accuracy of the MRIO tables relative to national SRIO benchmarks.

Regional value chain accounting for 2018 and 2020

To verify the validity and dynamic stability of the 2018 and 2020 China multi-regional input-output (MRIO) tables, this study compared consumption-based value added (CBVA) across Chinese provinces in 2017, 2018, and 2020 using data adjusted to 2020 prices. Figure 6 presents the CBVA across 15 sectors in 31 provinces for the years 2017, 2018, and 2020. The results reveal four distinct provincial patterns:(1) Continuously Rising Type: Mainly in eastern coastal and emerging central and western regions such as Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hunan, and Sichuan. Jiangsu (+246.8 billion yuan) and Guangdong (+131.7 billion yuan) showed the largest CBVA growth, driven by services, construction, and high-end manufacturing. For example, Jiangsu’s CBVA in transportation equipment manufacturing rose from 176.8 billion to 376.4 billion yuan. Education, healthcare, public administration (+745.5 billion yuan), services (+501.8 billion yuan), and construction (+405.4 billion yuan) also steadily grew, serving as key drivers of CBVA expansion. (2) Increase-Then-Decrease Type: Includes traditional industrial and service-oriented provinces such as Beijing, Liaoning, and Henan, as well as provinces like Qinghai, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Hainan. Beijing’s service CBVA rose 32% from 114.1 billion to 150.7 billion yuan in 2018 but dropped to 130.9 billion yuan in 2020. Hainan’s service CBVA increased slightly in 2018 but fell sharply by 56% in 2020. This decline was mainly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which severely affected high-contact sectors such as tourism, catering, and offline services, leading to a significant reduction in service consumption and thereby suppressing CBVA growth in the service sector. (3) Continuous Decline Type: Provinces such as Heilongjiang, Xinjiang, and Hubei showed steady CBVA decreases over the period. For instance, Xinjiang’s service CBVA fell from 34.5 billion yuan in 2018 to 29.83 billion yuan in 2020, mainly due to declines in transportation (–80.2 billion yuan). However, education, healthcare, and public administration sectors continued growing, with CBVA rising from 300.8 billion to 396.9 billion yuan. This indicates that spending on public services and healthcare increased significantly during the pandemic, becoming a key pillar supporting regional CBVA. (4) Decrease-Then-Increase Type: Includes Shanxi, Shandong, Jiangxi, Jilin, and Hebei. For example, Shandong’s service sector grew from 127.1 billion to 165.1 billion yuan, while public service spending rose from 96.4 billion to 128.3 billion yuan. Overall, provincial changes in consumption-based value-added highlight regional disparities in industrial structure and resilience, supporting the validity and stability of the MRIO model for regional economic analysis.

(4) Decrease-Then-Increase Type: This group includes regions such as Shanxi, Shandong, Jiangxi, Jilin, and Hebei. For example, Shandong and Hebei experienced declines in construction and manufacturing in 2018, but saw a recovery in 2020, driven by growth in the service sector and public sectors such as education and healthcare. In Shandong, the service sector and public service spending were the top two contributors to CBVA growth, rising from 127.08 billion yuan to 165.04 billion yuan and from 96.42 billion yuan to 128.28 billion yuan, respectively. Similarly, in Hebei, these sectors led the CBVA rise, with the service sector growing from 49.56 billion to 79.12 billion yuan and public service spending from 46.21 billion to 65.96 billion yuan.

Data availability

These MRIO tables are publicly available via the China Emission Accounts and Datasets (CEADs, www.ceads.net) and Figshare46 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29927291).

Code availability

The programs used in the data generation is based on MATLAB and GAMS. The code can be found in https://github.com/LiJie20230/China_MRIO.

References

Bednarski, L., Roscoe, S., Blome, C. & Schleper, M. C. Geopolitical disruptions in global supply chains: a state-of-the-art literature review. Production Planning & Control 36, 536–562 (2025).

Xing, Y. China and global value chain restructuring. China Economic Journal 15, 310–329 (2022).

Guan, D. et al. Global supply-chain effects of COVID-19 control measures. Nature human behaviour 4, 577–587 (2020).

Xing, Y. Decoding China’s export miracle: A global value chain analysis. (World Scientific, 2021).

Handfield, R. B., Graham, G. & Burns, L. Corona virus, tariffs, trade wars and supply chain evolutionary design. International Journal of Operations Production Management 40, 1649–1660 (2020).

Wu, J., Wood, J., Oh, K. & Jang, H. Evaluating the cumulative impact of the US–China trade war along global value chains. The World Economy 44, 3516–3533 (2021).

Bo, M. & Ankai, X. Rising risks to global value chains, (2021).

Itakura, K. Evaluating the impact of the US–China trade war. Asian Economic Policy Review 15, 77–93 (2020).

Huang, Y., Lin, C., Liu, S. & Tang, H. Trade networks and firm value: Evidence from the US-China trade war. Journal of International Economics 145, 103811 (2023).

Pu, M. & Zhong, Y. Rising concerns over agricultural production as COVID-19 spreads: Lessons from China. Global food security 26, 100409 (2020).

NBSC. Monthly Report on Manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index, https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202007/t20200701_1771424.html (2020).

Lin, J. et al. China’s international trade and air pollution in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 1736–1741 (2014).

Panwar, R., Pinkse, J. & De Marchi, V. The future of global supply chains in a post-COVID-19 world. California Management Review 64, 5–23 (2022).

Xia, C. et al. Outsourced carbon mitigation efforts of Chinese cities from 2012 to 2017. Nature Cities 1, 480–488 (2024).

Xia, C. et al. Heterogeneity in carbon footprint trends and trade-induced emissions in China’s urban agglomerations. Communications Earth & Environment 6, 723 (2025).

Zheng, H. et al. Rising carbon inequality and its driving factors from 2005 to 2015. Global Environmental Change 82, 102704 (2023).

Zheng, H. et al. Regional determinants of China’s consumption-based emissions in the economic transition. Environmental Research Letters 15, 074001 (2020).

Li, S. et al. Revisiting Copenhagen climate mitigation targets. Nature Climate Change 14, 468–475 (2024).

Huo, J., Meng, J., Zheng, H., Parikh, P. & Guan, D. Achieving decent living standards in emerging economies challenges national mitigation goals for CO2 emissions. Nature Communications 14, 6342 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Implications of demographic policies on China’s food-related environmental footprints amid population ageing. Global Environmental Change 95, 103082 (2025).

Zhang, Z., Yu, Y., Zheng, H. & Tian, P. The intersecting impact of aging and affluence on China’s household carbon emissions. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 115, 107997 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Liu, Y. & Li, J. The methodology and compilation of China multi-regional input-output model. Stat. Res 29, 3–9 (2012).

Zhang, Z., Shi, M. & Zhao, Z. The compilation of China’s interregional input–output model 2002. Economic Systems Research 27, 238–256 (2015).

Liu, W., Tang, Z., Han, M., Li, F. & Liu, H. The 2012 China multi-regional input-output table of 31 provincial units. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2018).

Liu, W., Li, X., Liu, H., Tang, Z. & Guan, D. Estimating inter-regional trade flows in China: A sector-specific statistical model. Journal of Geographical Sciences 25, 1247–1263 (2015).

Liu, W., Tang, Z., Chen, J. & Yang, B. China’s interregional input-output tables between 30 provinces in 2010. China Statistics Press (2014).

Liu, W. et al. Theories and practice of constructing China’s interregional input-output tables between 30 provinces in 2007. China Statistics Press (2012).

Mi, Z. et al. A multi-regional input-output table mapping China’s economic outputs and interdependencies in 2012. Scientific data 5, 1–12 (2018).

Zhao, Q. et al. An inter-regional input-output table series of China from 1987–2017 with integrated carbon emission data. Scientific Data 11, 1335 (2024).

Zheng, H. et al. Chinese provincial multi-regional input-output database for 2012, 2015, and 2017. Scientific data 8, 244 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. An inter-city input-output database distinguishing firm ownership in the Greater China area during 2002–2017. Scientific data 12, 723 (2025).

Zheng, H. et al. Linking city‐level input–output table to urban energy footprint: Construction framework and application. Journal of Industrial Ecology 23, 781–795 (2019).

Zheng, H. et al. Entropy-based Chinese city-level MRIO table framework. Economic Systems Research 34, 519–544 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Consumption‐based carbon emissions of 85 federal entities in Russia. Earth’s Future 12, e2023EF004323 (2024).

Zheng, H. et al. Leveraging opportunity of low carbon transition by super-emitter cities in China. Science Bulletin 68, 2456–2466 (2023).

Wang, Y., Geschke, A. & Lenzen, M. Constructing a time series of nested multiregion input–output tables. International Regional Science Review 40, 476–499 (2017).

Jahn, M. Extending the FLQ formula: a location quotient-based interregional input–output framework. Regional Studies 51, 1518–1529 (2017).

Sargento, A. L., Ramos, P. N. & Hewings, G. J. Inter-regional trade flow estimation through non-survey models: An empirical assessment. Economic Systems Research 24, 173–193 (2012).

NBSC. China regional input-output table (in Chinese: 中国地区投入产出表-2017). (China Statistical Publishing House, 2020).

Bekker, J. & Aldrich, C. The cross-entropy method in multi-objective optimisation: An assessment. European Journal of Operational Research 211, 112–121 (2011).

Batty, M. Reilly’s challenge: new laws of retail gravitation which define systems of central places. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 10, 185–219 (1978).

Yamada, M. Construction of a multi-regional input-output table for Nagoya metropolitan area, Japan. Journal of Economic Structures 4, 1–18 (2015).

Anderson, J. E. The gravity model. J Annu. Rev. Econ. 3, 133–160 (2011).

Wei, W. et al. A 2015 inventory of embodied carbon emissions for Chinese power transmission infrastructure projects. Scientific Data 7, 318 (2020).

Többen, J. On the simultaneous estimation of physical and monetary commodity flows. Economic Systems Research 29, 1–24 (2017).

Li, J. et al. China’s Provincial Multi-Regional Input-Output Database for 2018 and 2020, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29927291 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely acknowledge the support of the Carbon Neutrality and Energy System Transformation programme and the anonymous reviewers. This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFE0113000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (72361137002,72522023) and the Energy Economics Submission Fee Fund (0140-9883/©2025 Elsevier B.V.). Additional funding was provided by the European Union under grant agreement no. 101137905 (PANTHEON) and the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (AoE/P-601/23-N). D.G. acknowledges the support by the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the Xplorer Prize and the AXA Chair Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. designed the study and led the project. J.L. conducted the modelling. J.L., Z.Z., D.L., Q.O., P.T., D.G., and H.Z. contributed to the writing. J.L., Z.Z., and H.Z. collected the raw data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Zhang, Z., Liang, D. et al. China’s Provincial Multi-Regional Input-Output Database for 2018 and 2020. Sci Data 13, 222 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06543-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06543-y