Abstract

A pump-probe scheme for monitoring the electron dynamics of the excited state has been investigated by numerically solving the two-state time-dependent Schrödinger equation based on the non-Born-Oppenheimer approximation. By adjusting the delay time between a mid-infrared probe pulse and an ultra violet pump pulse, an obvious minimum can be seen in the higher-order harmonic region. With electron probability density distribution, ionization rate and classical simulation, the minimum can be ascribed to the electron localization around one nucleus at larger delay time and represents the electron dynamics of the excited state at the time of ionization. Moreover, the position of the minimum is much more sensitive to the nuclear motion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To trace the dynamic processes in atoms and molecules, researchers have made big process in the development of the ultrashort laser pulse1. Nowadays the pulse with duration of 67 as has been achieved experimentally2, which makes it possible to probe, manipulate and control the electron dynamics in photochemistry and attosecond physics3. Based on the pump-probe scheme4, 5, Bandrauk et al. have observed the attosecond electron motion between coherent electronic states by measuring the photoelectron signal and the photoelectron angular distribution as function of the pump-probe delay time (t del )6, 7. In this scheme, the duration of the probe pulse is shorter than the electron oscillatory period. Moreover, it’s known that the high-order harmonic generation (HHG) can be well explained by three-step model8: firstly, the electron tunnels through the potential barrier, and then is accelerated in the external field; finally, when the laser field changes its direction, the electron may return and recombine with the parent ion with the emission of harmonic photons. The highest harmonic energy is I p + 3.17 U p , where I p is the ionization potential and \({U}_{p}=\frac{{E}^{2}}{4{\omega }^{2}}\) is the ponderomotive energy with E and ω being the peak amplitude and the laser frequency, respectively. So each step in HHG process occurs on the femtosecond or attosecond time scale, in other words, the electron dynamics can also be traced by the high time-revolution HHG spectrum8, 9. Moreover, many interesting physical phenomena have been found with the infrared or mid-infrared probe pulse. Wang et al. have shown that the minimum electron probability density distribution of Rydberg atom corresponds to the dip-node structure on the harmonic spectrum10, 11. Wörner et al. have reported experimentally that both the harmonic amplitude and phase can detect the chemical reaction based on the harmonic interference between the excited and ground states12, 13. Bandrauk et al. have monitored the coherent attosecond dynamics and manipulated the interferences by adjusting the population of electronic states and the t del 14, 15. Kraus et al. have provided the experimental demonstration about measuring an electronic coherence through HHG16.

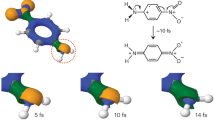

In previous studies, the lower-order harmonics have been widely used to detect the electron dynamics of the excited state17,18,19. It’s found that the excited state manifests the dynamics in the hollow region originating from the two-center interference17 or the resonance region between the ground state and the excite state18, 19. How do the higher-order harmonics code the electron dynamics of the excited state, which play a key role in the generation of ultrashort pulse1? Considering the fast dissociation of \({{\rm{H}}}_{2}^{+}\) at excited state blurring some dynamic information, we have adopted the pump-probe scheme to prepare \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) in the superposition state of the ground and excited states to further detect the electron dynamics of the excited state with the higher-order harmonics by solving the two-state time-dependent Schrödinger equation (TDSE) based on the non-Born-Oppenheimer (NBO) approximation. By adjusting the t del , the spectral minimum can be observed at large t del in the higher-order harmonic region, which can be viewed as a signature of the electron dynamics of the excited state. The time-frequency distribution, classical kinetic energy map and ionization rate distribution are adopted to reveal the underlying physical mechanism.

Results

The model of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) is initially in the electronic and vibrational ground state, and the corresponding I p of the ground state (1sσ g ) is 31.1 eV at R = 2.6 a.u. (the equilibrium separation). We first adopt an ultra violet pump pulse with the wavelength of 148 nm to excite part of wave packets into the repulsive first excited state (2pσ u ) via one-photon resonance. The electric field of the pump pulse \(E(t)=-\frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial }{\partial t}A(t)\) is displayed in Fig. 1(a). Here A(t) is the vector potential with sine-squared envelope \(A(t)=-\frac{c}{\omega }{E}_{0}{\rm{si}}{{\rm{n}}}^{2}(\pi t/{t}_{tot}){\rm{\sin }}(\omega (t-{t}_{tot}\mathrm{/2))}\). The total duration (t tot ) and the peak intensity are 2 fs and 1.0 × 1012 W/cm2, respectively. And then the molecular ion will be prepared on a coherent superposition of 1sσ g state and 2pσ u state. Moreover, the wave packets at 1sσ g state mainly distribute around the equilibrium distance as shown in Fig. 1(b) while those at 2pσ u state propagate to larger internuclear distance along the potential curve as shown in Fig. 1(c). At end of the pump pulse, the total excitation probability (i.e. population of the 2pσ u state) is 2.7%. After a t del , the initial coherent superposition wave packets are evolved by a mid-infrared probe pulse with identical vector potential to the pump pulse to generate intense harmonics. Here, the t del is defined as the time difference between the ending of the pump pulse and the beginning of the probe pulse. The wavelength, total duration and peak intensity of the probe pulse are 1600 nm, 10 fs and 3.0 × 1014 W/cm2, respectively. Furthermore, the related harmonic spectra as function of t del are plotted in Fig. 1(d). Interestingly, the harmonic intensities decay in the higher-order harmonic region at larger t del (i.e. from t del = 8 fs to t del = 10 fs) as the dash arrow depicted. Moreover, the position of spectral minimum shifts as function of t del . In the following section, we will discuss these findings in detail.

Discussion

With the initial coherent superposition of the 1sσ g and 2pσ u states, four channels can contribute to the HHG process. On the one hand, the electron can be ionized from and recombine to the 1sσ g (2pσ u ) state, i.e. H11 channel (H22 channel). On the other hand, it can also be ionized from the 1sσ g (2pσ u ) state and recombine to the 2pσ u (1sσ g ) state, i.e. H12 channel (H21 channel). As reported by Bredtmann et al. in previous studies9, 14, 15, two states tend to lose the nuclear overlap with the increase of the t del so that only H11 channel and H22 channel contribute to the harmonic emission at larger t del . Moreover, we have simulated that the harmonic efficiency of the 1sσ g state is over 6 orders of magnitude lower than that of the 2pσ u state for t del = 0 fs, and the difference of harmonic intensity can be further enhanced at larger t del . Accordingly, the excited state plays an important role in harmonic emission. Furthermore, it is the electron dynamics of the excited state that induces the spectral minima as the arrow illustrated in Fig. 1(d).

To uncover the underlying mechanism, the harmonic spectrum from the superposition state for t del = 10 fs has been shown in Fig. 2(a), which exhibits an obvious dip from 175th to 189th. The corresponding time-frequency map from 4 fs to 7 fs illustrates the electron dynamics in the probe field both in frequency and time dimensions in Fig. 2(b). It can be seen that the minimum noted by rectangle in harmonic spectrum corresponds to the weak harmonic emission from 5.2 fs to 5.4 fs noted by dash ellipse in time-frequency map. What is the source of the spectral minimum for single-electron system \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\), the phase difference between the propagating and residual wave packets12, 13 or the two-center interference17? Since there is no longer nuclear overlap between the 1sσ g state and the 2pσ u state for t del = 10 fs, the minimum is distinct from the dynamical minimum arising from the destructive phase difference with the returning wave packet in acceleration process. To check whether the minimum resulting from the two-center interference, the internuclear distance of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) initially at 2pσ u state calculated by \(R(t)=\frac{\iint RdRdz{|\psi (R,z;t)|}^{2}}{\iint dRdz{|\psi (R,z;t)|}^{2}}\) has been displayed in Fig. 2(c) due to its dominated role in harmonic emission. For the 2pσ u state with an antisymmetric orbital17, the two-center interference is governed by the term \(I(k)={e}^{-ik\cdot R\mathrm{/2}}-{e}^{ik\cdot R\mathrm{/2}}=-2i\,\sin (k\cdot R\mathrm{/2)}\), where I(k) is the harmonic intensity, k is the electron momentum and R is the internuclear distance. The two-center interference minima are expected to occur when the argument of the sine is the integral multiple of 2π, i.e. k · Rcosα = 2nπ and \({N}_{min}\omega ={k}^{2}\mathrm{/2(}n=0,1,2\ldots ,)\), where N min is the harmonic order at the two-center interference minimum and ω is the laser frequency of the probe pulse. For the two-center interference minimum from 175th to 189th at 2pσ u state, the internuclear distance should satisfy with R = 1.91 n ~1.98 n (n is integer) at recombination moment. So the internuclear distance should be around 7.6 a.u. (n = 4) and 9.5 a.u. (n = 5) as arrows depicted in Fig. 2(c) during the time region from 5.2 fs to 5.4 fs. However, the related internuclear distance of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) changes from 8.7 a.u. to 8.9 a.u. Consequently, the minimum cannot be ascribed to the two-center interference. As discussion above mentioned, the causative effect can not be found from the electron dynamics both in acceleration and recombination processes. How about the electron dynamics in ionization process?

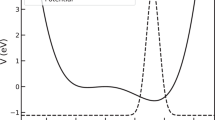

To further discuss the effect of the ionization process on spectral minimum, we have calculated the probability distributions of the electron initially at the 1sσ g and 2pσ u states in the probe field by \(P(z,t)={\int }_{1.0}^{26.65}{|\psi (R,z;t)|}^{2}dR\) in Fig. 3. Kamta et al. have revealed that in a strong field the σ u electron always localizes in the direction of the field whereas the σ g electron localizes opposite to the field20. This is due to the difference in polarizability that all ground states have negative polarizability and Stark shifts whereas excited states change sign20. As shown in Fig. 3(a), the electron initially at 1sσ g state oscillates around two nuclei, which is opposite to the direction of the probe field (green line). However, the electron initially at 2pσ u state presents different characters for different t del . The electron mainly distributes around z = 0 for t del = 0 fs in Fig. 3(b) while with the increase of the t del , it tends to localize in the region of z < 0 obviously after t = 4 fs as shown in Fig. 3(c) and (d). Here t = 0 fs represents the beginning of the probe pulse. In the probe field, the electron initially at 2pσ u state with antisymmetric distribution around t = 0 fs (as red arrow shown) may experience such physical processes: firstly, when the intensity is lower at the beginning of the probe pulse, the wave packet at 2pσ u state will be transferred to the 1sσ g state, and then spreads to the larger internuclear distance; finally, with the increase of the laser intensity, the wave packet experiences the complete ionization-acceleration-recombination process to generate efficiency harmonics. For t del = 0 fs, the initial wave packet at 2pσ u state localizing around 2.6 a.u. can be easily transfered to the 1sσ g state between t = 0 fs to t = 2 fs, and then oscillates in the bottom of the potential cure of 1sσ g state which induces the electron density distribution mainly around z = 0 as shown in Fig. 3(b). However, the spread of the wave packet will be more obvious in the probe field after the transfer process when the initial wave packet at 2pσ g state distributes in larger internuclear distance for larger t del . For example, the electron density distributes prominently in the region of z < 0 after t = 4 fs for t del = 5 fs as displayed in Fig. 3(c). What’s more, for t del = 5 fs, the electron mainly localizes in the region of z < 0 as depicted in the rectangle around t = 7 fs whereas it should localize in the region of z > 0 as reported by Kamta et al.20. Moreover, this counter-intuitive phenomenon tends to appear at earlier time with the increase of t del (e.g. around t = 3 fs for t del = 10 fs shown in Fig. 3(d)). To get the abnormal phenomenon across, the electron motion in double-well potential at different times will be illustrated in Fig. 4. From the internuclear distance of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) (black solid line) initially at 2pσ g state for t del = 5 fs in Fig. 4(a), the internuclear distances are 5.35 a.u. at t = 3 fs (as red arrow pointed) and 7.15 a.u. at t = 7 fs (as blue arrow pointed), respectively. And then the combined energies of the Coulomb potential and the static potential of 5.35 a.u.(thick line), 7.15 a.u. (thin line) for t del = 5 fs and 7.75 a.u. at t = 3 fs (dotted line) for t del = 10 fs are plotted in Fig. 4(b), respectively. With lower and narrower inner potential barrier under the condition of 5.35 a.u. at t = 3 fs, the electron can easily transit from the higher potential well to the lower one (as blue crooked arrow shown) and then tunnels though the potential well (as red horizontal arrow shown). However, the inner potential barrier becomes higher and wider with the nuclear separation. In this case, the transfer process will be suppressed, which probably induces the electron localization around the nucleus in the region of z < 0 around t = 7 fs for t del = 5 fs. And then the related ionization process will also be suppressed. So does for the case of t del = 10 fs. Moreover, the ionization rate distributions P ion (R, t) for t del = 5 fs and t del = 10 fs have also been provided in Fig. 5(c) and (d), which can be obtained based on the flux operator \({P}_{ion}(R,t)=IM[\langle \psi (R,z;t)|\delta (z-{z}_{s})\frac{\partial }{\partial z}|\psi (R,z;t)\rangle ]\), where z s = 40 a.u. represents the position for flux analysis. Obviously, the ionization rate is much lower when the electron distributes in the region of z < 0 in negative probe field as the double-arrow shown, which further verifies the electron dynamics above analyzed. In general, the electron localization will be abnormal when the internuclear distance is larger than 6.7 a.u. (i.e. t > 6.1 fs for t del = 5 fs). Moreover, it agrees well with the result reported by Fujimura et al.21 that the electron distribution is counter-intuitive in the coupling region of 1sσ g and 2pσ u states. Therefore, the minimum is probably ascribed to the suppression of the ionization process when the potential curves of two lowest electronic states couple together. Additionally, the wave packet tends to spread to 6.8 a.u. around t = 3 fs in the probe field for t del = 8 fs so that the electron localization in the region of z < 0 would lead to the ionization suppression. Thus the obvious spectral minimum can be clearly seen for t del > 8 fs in Fig. 1(d). Next, we will further explore the mechanism of position shifting as function of t del shown in Fig. 1(d).

(a) The probability distribution of electron initially at 1sσ g state in the probe field. The green line illustrates the electric field of the probe pulse. (b–d) The probability distributions of electron initially at 2pσ u state in the probe field for t del = 0 fs, t del = 5 fs and t del = 10 fs, respectively.

(a) The time-dependent internuclear distance of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) in the probe field with initial 2pσ u state for t del = 5 fs. (b) The combined energy of the Coulomb potential and static electric field potential at t = 3 fs (thick line), t = 7 fs (thin line) for t del = 5 fs and t = 3 fs (dotted line) for t del = 10 fs, respectively. The dot represents the electron.

Figure 6(a) illustrates the time-frequency map of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) from t = 2 fs to t = 7 fs for t del = 8 fs. In this condition, the spectral minimum distributes in lower energy region from 125th to 141th (as black dash line shown) compared with the case of t del = 10 fs shown in Fig. 2(b). As the spectral minimum origins from the ionization suppression, the classical simulation by solving the Newton’s equations of motion22, 23 can be used to judge the ionization moments for different t del . Seen from Fig. 6(b), the internuclear distance changes far less than \(\frac{E}{{\omega }^{2}}\) for t del = 8 fs, so similar cutoff energies can be obtained both from the recombinations with parent nucleus and neighboring nucleus22. Here we just provide the classical simulation about the former case, moreover, the multiple rescattering events have also been neglected considering the appearance of the spectral minimum in first rescattering in quantum simulation. According to the discussion about the electron motion above mentioned, the ionization process of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) mainly takes place around t = 3 fs in the probe field when the internuclear distance is about 6.8 a.u. for t del = 8 fs, and the related I p = 0.79 a.u. corresponds to 27.7th harmonic order. The cutoff energy (about 284.7th harmonic order) based on the classical simulation agrees well with the quantum ones shown in Fig. 6(a) and (d). Furthermore, due to the critical role of the kinetic energy (about 257th harmonic order) obtained in the probe field, the cutoff energy is almost unchanged with the increase of t del as displayed in Fig. 1(d). As seen from the classical simulation from 3.1 fs to 3.3 fs depicted in Fig. 6(e), it is the ionization process from 3.18 fs to 3.23 fs (as magenta dash line shown) that contributes to the spectral minimum from 125th to 141th. Moreover, it corresponds to the lowest ionization rate for t del = 8 fs shown in Fig. 6(f). With the identical method, the lowest ionization rate for t del = 10 fs will shift to earlier moments from 3.06 fs to 3.1 fs, which means that the spectral minimum will exist in higher energy region with the increase of t del as shown in Fig. 1(d). In other words, the position of the spectral minimum depends on the nuclear motion.

(a) The time-frequency map of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) with initial superposition state for t del = 8 fs. (b) The time-dependent internuclear distance of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) with initial 2pσ u state in the probe field. (c) and (d) are the classical kinetic energy map and related harmonic spectrum, respectively. (e) The enlargement of (c) from 3.1 fs to 3.3 fs. (f) The corresponding ionization rate distribution.

In conclusion, the electron dynamics of the excited state has been detected with the higher-order spectral minimum by solving the two-state TDSE. With the increase of t del between the pump and probe pulses, the excited state tends to dominate the harmonic emission. Moreover, the electron localization around one nucleus in the coupling region of both electronic states would result in the suppression of ionization process. As a consequence, the spectral minimum can be observed in higher-order harmonic region with interesting characters: (i) the minimum appears at certain photon energy region; (ii) the position of the minimum shifts as function of t del . In general, this work will provide new insight into the electron dynamics of excited state in strong-field physics. Furthermore, with the close relationship to the nuclear motion, the spectral minimum may be used to probe the nuclear dynamics in turn.

Methods

The one-dimensional calculation of \({{\rm{T}}}_{2}^{+}\) has been performed to investigate the electron dynamics of the excited state via pump-probe scheme. Providing the linear pulse along with the molecular axis and ignoring the rotation of the molecule ion, the nuclear wave packets of two lowest electronic states (1sσ g state and 2pσ u state) can be obtained in the pump process by solving the two-state TDSE24, and then for each fixed t del , the harmonic emission from coherent state in the probe process can be obtained by solving the TDSE based on NBO approximation25, 26

where M is the mass of the nucleus, R is the internuclear distance and z is the electron coordinate (with respect to the nuclear center of mass).

The time-dependent wave function is advanced using the standard second-order split-operator method26, 27. In the numerical simulation, the converged numerical parameters are as follows: the grid ranges from 1.00 a.u. to 26.65 a.u. in R direction and from −202.50 a.u. to 202.50 a.u. in z direction, with a grid space of ΔR = 0.05 a.u. and Δz = 0.15 a.u. With the exponential decay mask function employed in the work, the corresponding absorbing positions are 50 grids and 100 grids away from the boundaries in R direction and z direction, respectively. The corresponding time step is 0.2 a.u. The HHG spectrum can be obtained by Fourier transforming the time-dependent dipole acceleration \(a(t)=\langle \psi (R,z;t)|-\frac{\partial {V}_{c}}{\partial z}+kE(t)|\psi (R,z;t)\rangle \) 22, 28, and the time-frequency distribution by means of the wavelet transform23, 29,30,31.

Data availability

Data generated during this study is included in this article.

References

Brabec, T. & Krausz, F. Intense few-cycle laser fields: frontiers of nonlinear optics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 545–591 (2000).

Zhao, K. et al. Tailoring a 67 attosecond pulse through advantageous phase-mismatch. Opt. Lett. 37, 3891–3893 (2012).

He, F., Ruiz, C. & Becker, A. Control of electron excitation and localization in the dissociation of H+ 2 and its isotopes using two sequential ultrashort laser pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 083002 (2012).

Kraus, P. M. & Wörner, H. J. Time-resolved high-harmonic spectroscopy of valence electron dynamics. Chem. Phys. 414, 32–44 (2013).

Hogle, C. W. et al. Attosecond coherent control of single and double photoionization in Argon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 173004 (2015).

Yuan, K. J. & Bandrauk, A. D. Monitoring coherent electron wave packet excitation dynamics by two-color attosecond laser pulses. J. Chem. Phys. 145, 194304 (2016).

Bandrauk, A. D., Chelkowski, S., Corkum, P. B., Manz, J. & Yudin, G. L. Attosecond photoionization of a coherent superposition of bound and dissociative molecular states: effect of nuclear motion. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 42, 134001 (2009).

Corkum, P. B. Plasma perspective on strong-field multiphoton ionization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 1994–1997 (1993).

Bredtmann, T., Chelkowski, S. & Bandrauk, A. D. Monitoring attosecond dynamics of coherent electron-nuclear wave packets by molecular high-order-harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. A 84, 021401(R) (2011).

Zhai, Z., Chen, J., Yan, Z. C., Fu, P. M. & Wang, B. B. Direct probing of electronic density distribution of a Rydberg state by high-order harmonic generation in a few-cycle laser pulse. Phys. Rev. A 82, 043422 (2010).

Chen, J. G., Yang, Y. J., Chen, J. & Wang, B. B. Probing dynamics information and spatial structure of Rydberg wave packets by harmonic spectra in a few-cycle laser pulse. Phys. Rev. A 91, 043403 (2015).

Wörner, H. J., Betrand, J. B., Corkum, P. B. & Villeneuve, D. M. High-harmonic homodyne detection of the ultrafast dissociation of Br2 molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 103002 (2010).

Wörner, H. J., Betrand, J. B., Kartashov, D. V., Corkum, P. B. & Villeneuve, D. M. Following a chemical reaction using high-harmonic interferometry. Nature (London) 466, 604–6072 (2010).

Chelkowski, S., Bredtmann, T. & Bandrauk, A. D. High-order-harmonic generation from coherent electron wave packets in atoms and molecules as a tool for monitoring attosecond electrons. Phys. Rev. A 85, 033404 (2012).

Chelkowski, S., Bredtmann, T. & Bandrauk, A. D. High-harmonic generation from a coherent superposition of electron states: controlling interference patterns via short and long quantum orbits. Phys. Rev. A 88, 033423 (2013).

Kraus, P. M. et al. High-harmonic probing of electronic coherence in dynamically aligned molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 243005 (2013).

Han, Y. C. & Madsen, L. B. Minimum in the high-order harmonic generation spectrum from molecules: role of excited states. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 43, 225601 (2010).

Bian, X. B. & Bandrauk, A. D. Multichannel molecular high-order harmonic generation from asymmetric diatomic molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 093903 (2010).

Feng, L. Q. & Chu, T. S. Role of excited states in asymmetric harmonic emission. Commun. Comput. Chem. 1, 52–62 (2013).

Bandrauk, A. D., Barmaki, S. & Kamta, G. L. Laser phase control of high-order harmonic generation at large internuclear distance: the H+-H2 + system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 013001 (2007).

Kawata, I., Kono, H. & Fujimura, Y. C. Adiabatic and diabatic responses of H+ to an intense femtosecond laser pulse: dynamics of the electronic and nuclear wave packet. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 11152–11165 (1999).

Zhang, C. P., Xia, C. L., Jia, X. F. & Miao, X. Y. Multiple rescattering processes in high-order harmonic generation from molecular system. Opt. Express 24, 20297–20308 (2016).

Zhang, C. P., Pei, Y. N., Xia, C. L., Jia, X. F. & Miao, X. Y. Theoretical research on multiple rescatterings in the process of high-order harmonic generation from a helium atom with a long wavelength. Laser Phys. Lett. 14, 015301 (2017).

Miao, X. Y., Wang, L. & Song, H. S. Theoretical study of the femtosecond photoionization of the NaI molecule. Phys. Rev. A 75, 042512 (2007).

Lu, R. F., Zhang, P. Y. & Han, K. L. Attosecond-resolution quantum dynamics calculations from atoms and molecules in strong laser fields. Phys. Rev. E 77, 066701 (2008).

Hu, J., Han, K. L. & He, G. Z. Correlation quantum dynamics between an electron and D+ 2 molecule with attosecond resolution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 123001 (2005).

Miao, X. Y. & Zhang, C. P. Manipulation of the recombination channels and isolated attosecond pulse generation from HeH+ with multicycle combined field. Laser Phys. Lett. 11, 115301 (2014).

Chu, T. S., Zhang, Y. & Han, K. L. The time-dependent quantum wave packet approach to the electronically nonadiabatic processes in chemical reactions. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 25, 201–235 (2006).

Li, L. Q. & Miao, X. Y. Theoretical exploration of the interference minimum in molecular high-order harmonic generation. J. At. Mol. Sci. 7, 1–10 (2016).

Tong, X. M. & Chu, S. I. Probing the spectral and temporal structures of high-order harmonic generation in intense laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 61, 021802(R) (2000).

Xia, C. L. & Miao, X. Y. Theoretical study of isolated attosecond pulse generation with two methods. J. At. Mol. Sci. 7, 17–24 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Prof. Keli Han and Dr. Ruifeng Lu for providing us the LZH-DICP code. This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11404204, 11274215, 11504221), Natural Science Foundation for Young Scientists of Shanxi Province, China (Grant No. 2015021023), Program for the Top Young Academic Leaders of Higher learning Institutions of Shanxi Province, China and Innovation Project for Postgraduates of Shanxi Province, China (Grant No. 2017BY085).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.P.Z. and X.Y.M. conceived the idea. C.P.Z. performed the calculations. C.P.Z., C.L.X., X.F.J. and X.Y.M. analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, CP., Xia, CL., Jia, XF. et al. Monitoring the electron dynamics of the excited state via higher-order spectral minimum. Sci Rep 7, 10359 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10667-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10667-6

This article is cited by

-

Quantum control and characterization of ultrafast ionization with orthogonal two-color laser pulses

Scientific Reports (2020)