Abstract

Each year ~5.4 million children and adolescents in the United States suffer from dental infections, leading to pulp necrosis, arrested tooth-root development and tooth loss. Apical revascularization, adopted by the American Dental Association for its perceived ability to enable postoperative tooth-root growth, is being accepted worldwide. The objective of the present study is to perform a meta-analysis on apical revascularization. Literature search yielded 22 studies following PRISMA with pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated to account for inter-examiner variation. Following apical revascularization with 6- to 66-month recalls, root apices remained open in 13.9% cases (types I), whereas apical calcification bridge formed in 47.2% (type II) and apical closure (type III) in 38.9% cases. Tooth-root lengths lacked significant postoperative gain among all subjects (p = 0.3472) or in subgroups. Root-dentin area showed significant increases in type III, but not in types I or II cases. Root apices narrowed significantly in types II and III, but not in type I patients. Thus, apical revascularization facilitates tooth-root development but lacks consistency in promoting root lengthening, widening or apical closure. Post-operative tooth-root development in immature permanent teeth represents a generalized challenge to regenerate diseased pediatric tissues that must grow to avoid organ defects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental caries are among the most prevalent infectious diseases of the mankind1,2,3. Severe caries occur in ~21% of children and adolescents with immature permanent teeth4. Approximately 7% of deep caries in immature permanent teeth develop dental-pulp necrosis5. Furthermore, ~25% of children and adolescents experience dental trauma, and among them, ~27% contract pulp necrosis6. Together, ~5.4 million children and adolescents in the United States each year suffer from caries- and trauma-elicited pulp necrosis and tooth loss7. Upon metastasis, microbials and toxins of dental origin may cause systemic infections such as cavernous sinus thrombosis, cerebral abscess, myocardial infarctions and endocarditis8,9.

Necrotic immature permanent teeth in children and adolescents are a formidable clinical challenge10. Analogous to hepatitis-elicited liver growth arrest in children11, caries or trauma can induce necrosis of dental pulp and developmental arrest of immature permanent teeth12. Whereas infections of most organs are treated by antibiotics, dental-pulp infections are recalcitrant to systemic anti-microbial therapies due to early-onset necrosis. Upon necrosis, tooth survival not only relies on local infection control, but also restoration of dental-pulp vitality13. Local antimicrobial therapy alone, while effective in controlling pulp infections, fails to revert arrested tooth-root growth13. Apexification is the current treatment for pulp necrosis in children and adolescents by filling the disinfected root canal with inert materials, but leads to ~45.9% post-operative tooth fractures in nine years14. Following tooth loss in children and adolescents, dental implants are contraindicated because metallic implants are embedded in the growing alveolar bone in children whose alveolar bone undergoes active growth, for which metallic implants cannot adapt15. Thus, pulp necrosis at pediatric age is a pandemic without a clinically satisfactory therapy, either before or after tooth loss.

Regenerative therapies that enable the treated necrotic immature permanent teeth to complete root development have been tirelessly pursued. In 1961, Nygaard-Østby reported the first recognized study of evoked bleeding16. Histologic sections from the patient’s extracted teeth showed ingrowth of vascularized connective tissue in the root canal16. Subsequently, the practice of evoked bleeding in clinically treated necrotic immature teeth proliferated14,17. In 2011, the American Dental Association (ADA) issued clinical codes (D3351, D3352 and D3354) for the practice of evoked bleeding, also known as apical revascularization (AR)13. Presently, teaching of AR is incorporated in postgraduate endodontics training programs in the United States8,9. The European Society of Endodontology recently adopted AR18. Dental and/or endodontic societies in China and several other Asian countries are in the process of adopting AR.

To date, no meta-analysis has been reported on AR’s efficacy. Bose et al. (2009) performed a retrospective evaluation of radiographic outcomes in immature teeth with necrotic dental pulp treated with apical revascularization5, with a collection of 54 published and unpublished clinical cases but without performing PRISMA or meta-analysis. The primary goal of Bose et al. (2009) was to compare two root-canal disinfection protocols. The primary objective of the present study is to perform a patient-level meta-analysis of tooth-root development among all qualified AR cases in the literature using PRISMA with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria19,20. As opposed to the majority of tissue-engineering work with a focus on regenerating adult tissues, AR aims to regenerate pediatric tissues, and is not considered successful unless the treated immature teeth complete root development12. In general, whether and how injured or damaged pediatric tissues regenerate to heal defects is largely elusive21,22. Necrotic immature teeth offer powerful models in both experimental animals and human patients for devising effective therapies that regenerate growing, pediatric tissues to complete organ development.

Results

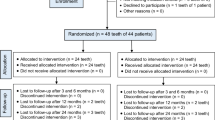

Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. The patients’ age range was 8-18 years old, reflective of the population with immature permanent teeth (Table 2). Although the included 36 cases were treated by clinicians from multiple continents including Americas, Asia, Australia, and Europe, disinfection and intra-canal medicament protocols were substantially similar (Table 2). Post-operative recalls ranged from 6 to 66 months (17.8 ± 11.6 months) (Table 2). Figure 1 shows PRISMA flow diagram. A total of 320 reports resulted from 616 hits following removal of duplicates. Next, a total of 268 studies were excluded: 91 with titles and abstract not meeting the inclusion criteria; 76 review articles; 47 non-human animal studies; 51 for treatment without AR performed; and 3 in non-English language (Fig. 1). Among the resulting 52 articles, 30 were further excluded: 13 without adjacent reference teeth or anatomic reference points; 11 with immature reference teeth; 5 without dental radiographs or poor radiographic quality and one remaining study with <6-month recall (Fig. 1). Thus, 22 full-length articles that fit the pre-defined inclusion criteria and were immune from the pre-defined exclusion criteria were selected for meta-analysis, with a total of 36 cases (Table 2). The Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the tooth length ratio, the optical width ratio, and the root area ratio were 0.85, 0.47, and 0.73, respectively, indicating that strong inter-examiner agreement for tooth length ratio and root area ratio but moderate for apical width ratio.

PRISMA flow chart. PRISMA guidelines were strictly followed19,20. Out of 616 records emerged, duplicates removed to yield 320 full-length publications. Cases were excluded using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 1. Titles and abstracts of the 320 full-length studies without reviewing any data in each report’s Result section, and excluded 268 studies to yield the resulting 52 studies. The full text of the 52 full-length reports were carefully reviewed to further exclude 30 studies, with specific reasons as stated, to yield the final 22 studies included in meta-analysis with a total of 36 clinical cases.

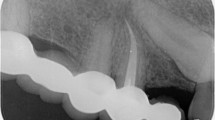

Tooth-root lengths and root/crown ratios are of paramount importance to fracture rates and hence tooth loss23. Three cases were demonstrated in Fig. 2, which were selected from the included 36 patients to illustrate not only representative clinical outcome of tooth-root development and its diversity following AR, but also intrinsic radiographic image distortion. In Case 1 (PMID 15085044, corresponding to Patient #1 in Table 2), AR was performed in the necrotic second mandibular premolar of an 11-year-old male (Table 2). The absolute tooth-root length (red line) indeed increased at 6-, 12- and 18-month recalls, so was root length of the reference tooth (blue line) also increased (Supplemental Clinical Data 1: Patient 1), with virtually no increases in root-length ratios: 0.88, 0.90, 0.87 and 0.86 (Fig. 2A–D), suggesting little increase in root length following AR. Apical closure occurred at 18 months (Fig. 2D), suggesting that apical closure is not necessarily associated with root lengthening. Apical radiolucency was resolved at 6-, 12- and 18-month recalls (Fig. 2B–D). Case 2 (PMID 23146641, corresponding to Patient #21 in Table 2) represents a necrotic central incisor of a 16-year-old female (Fig. 2E). The linear tooth-root lengths of the treated tooth (red line) indeed increased at 6- and 12-month recalls, but so were the root lengths of the reference tooth (blue line) (Supplemental Clinical Data 1: Patient 21) (Fig. 2F,G). Accordingly, root-length ratios showed no substantial increases: 0.92, 0.93 and 0.94 for pre-treatment and 6- and 12-month recalls (Fig. 2E–G), suggesting little gain in root lengths. Apical calcification bridge (ACB) was present at both 6- and 12-month recalls (Fig. 2F,G). Apical radiolucency was modest before treatment (Fig. 2E), but became pronounced at 6- and 12-month recalls (Fig. 2F,G). Case 3 (PMID 24332005, corresponding to Patient #27 in Table 2) is a necrotic second mandibular premolar of an 11-year-old female (Fig. 2H). The root-length ratios were 0.77 pre-treatment and 0.88 by the 12-month recall (Fig. 2I), indicative of root lengthening. Remarkably, there was no apical closure, suggesting that apical closure and root lengthening are not necessarily associated with each other. Substantial pre-treatment apical radiolucency was resolved at 12 months (Fig. 2I). Table 3 provides root-length ratios of all 36 included cases. Statistical analysis of root-length ratios of all 36 cases lacked post-operative gain (p = 0.3472) (Fig. 3A), contrasting to self-reported 52.8% root lengthening in 19 of the 36 cases (Supplemental Table 1). Plots of root-length ratios of 36 cases are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1A. Radiographic images of all 36 included clinical cases with and without current tooth-length measurements are provided in Supplemental Clinical Data 1 and 2 for any interest in verifying data validity and reproducibility.

Illustrated clinical cases of apical revascularization. Three cases illustrate not only representative clinical outcome and its diversity, but also intrinsic radiographic image distortion. The linear tooth-root length of the treated tooth (red lines); root lengths of the reference tooth (blue lines). In Case 1 (PMID 15085044), apical revascularization performed in the second mandibular premolar (P2) of an 11-year-old male patient (A), with 6-, 12- and 18-month recalls (B,C,D, respectively). Root-length ratios: 0.88, 0.90, 0.87 and 0.86. Apical closure at 18-month recall (D). Apical radiolucency resolved at 6-, 12- and 18-month recalls. In Case 2 (PMID 23146641), a necrotic central incisor of a 16-year-old female patient with arrested root-apex development (E) treated with apical revascularization and recalls at 6- and 12-months (F,G, respectively) with root-length ratios at 0.92, 0.93 and 0.94. Apical calcification bridge at both 6- and 12-month recalls (F,G). Modest apical radiolucency before treatment (E), but apparently became pronounced at 6- and 12-month recalls (F,G). In Case 3 (PMID 24332005), a necrotic second mandibular premolar of an 11-year-old female patient with arrested root-apex development (H) treated with apical revascularization, and 12-month recall (I). Root-length ratios at 0.77 to 0.88. No apparent apical closure at 12-month recall (I). Substantial pre-treatment apical radiolucency (H) resolved at 12 months (I).

Statistical analysis of tooth-root development following apical revascularization. (A) Tooth-root length ratios of all 36 included clinical cases revealing no significant postoperative root lengthening (p = 0.3472). (B) Apical width ratios of all 36 included clinical cases revealing significant postoperative narrowing of root apices (p < 0.0001), but this significance is restricted to types II and III cases, not type I patients (c.f. Supplemental Fig. 2B). (C) Root-dentin area ratios of all 36 included clinical cases revealing significant increase in postoperative root-dentin area (p = 0.0003), but this significance is restricted to types III cases, not type I and II patients (c.f. Supplemental Fig. 3B).

Another important indication of tooth-root development is apical closure, or lack thereof, because immature permanent teeth without apical closure are 2.75 times more likely to fracture than fully mature teeth24. Apical closure status of post-operative immature permanent teeth was divided into three categories in reference to Moorrees stages of normal root development25. Type I occurred in 5 out of 36 cases at 13.9% (Fig. 4 top row), with open apices comparable to pre-intervention (Supplemental Movie 1A), as in the demonstrated Case 3 in Fig. 2H,I. Type II occurred in 17 cases and consisted of the majority of the included 36 cases at 47.2% (Fig. 4 middle row), with ACB formation (Supplemental Movie 1B), as the demonstrated Case 2 in Fig. 2E–G. Type III occurred in 14 out of 36 cases at 38.9% with apical closure (Fig. 4 bottom row, and Supplemental Movie 1C), as the demonstrated Case 1 in Fig. 2A–D. Contrastingly, only one out of the total 36 cases was self-reported as no apical closure at 2.8% (Supplemental Table 2). Apical closure was self-reported in 25 cases at 69.4%, along with no self-reporting on apical closure status in 10 cases at 27.8% (Supplemental Table 2). To resolve this discrepancy between self-reported apical closure status (Supplemental Table 2) and the present evaluation (Fig. 4), apical-width ratios were measured by dividing the linear apical-opening width against tooth-crown width at CEJ. Relatively high fidelity emerged in apical-width ratios (Supplemental Fig. 2A) with author-graded apical closure status (Fig. 4). Type I cases showed no significant apical narrowing (p = 0.1568), but apical narrowing was present in both types II cases (p = 0.0002; slope: −0.00261) and III cases (p < 0.0001; slope: −0.00655) (Supplemental Fig. 2B).

Three types of apical development following apical revascularization. We divided root development of immature permanent teeth into three subgroups following therapeutic intervention, such as apical revascularization. Type I represents little or no postoperative apical narrowing, with open apices comparable to pre-intervention. Type I occurred in 5 of the included 36 cases at 13.9% (top diagram; also c.f. Supplemental Movie 1A). Type II represents apical calcification bridge formation, and occurred among 17 of the included 36 cases at 47.2% (middle diagram; also c.f. Supplemental Movie 1B). Type III represents apical closure to a degree similar to a fully mature tooth that has completed root development, and occurred among 14 of the included 36 cases at 38.9% (bottom diagram; also c.f. Supplemental Movie 1C).

Tooth-root lengthening was further analyzed among types I, II and III subgroups and again found no significant post-operative root-length gain in any subgroup: p = 0.1546 for type I, p = 0.4981 for type II, and p = 0.2439 for type III (Supplemental Fig. 1B). The average root-dentin area ratio showed significant post-operative gain (p = 0.0003), but this gain was restricted to type III apical closure cases (p < 0.0001), with no significant gain in root-dentin area ratio among type I or II cases (Supplemental Fig. 3B). Type II was associated with a significant decrease in root-dentin area ratio (p = 0.0229) (Supplementary Fig. 3B), likely due to enlarged root-canal space following curved ACB formation. Root-area ratios showed high fidelity in differentiating type III from types I and II cases. Per receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, type I was associated with root-area ratios < 0.58, type II between 0.58 and 0.79, and type III > 0.79.

Apical radiolucency in patients with necrotic dental pulp suggests metastasis of microbial infections to the peri-apical space. Peri-apical infections are severe clinical conditions, and if left untreated, may cause systemic infections8,9. With a uniform standard and by stratifying apical radiolucency into four categories, apical radiolucency indeed was resolved in 26 out of the total 36 cases at 72.2% (Supplemental Table 3). However, apical radiolucency remained present in 8 cases at 22.2% (Supplemental Table 3). Two cases were free from pre-treatment and post-operative apical radiolucency, accounting for 5.6% (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

Coagulated blood is perceived to harbor factors that heal tissue defects26,27. As a clinician initiated “regenerative” procedure, AR is analogous to other blood-clotting therapies such as microfracture in orthopedics where blood from bone marrow is induced to coagulate in focal articular cartilage defects for cartilage regeneration28. Can the same circulating blood induce the regeneration of different tissues such as articular cartilage and mineralized dentin? The intuitive answer might be that coagulated blood only serves as a scaffold, and the local environment determines what tissue is regenerated. However, local regenerative cues likely are insufficient to heal the defect in the first place, or otherwise there is no defect. What blood components, if any, activate local cues to regenerate specific tissues warrants experimental studies. Bioactive cues, local and/or blood-derived, must form a chemotactic gradient to recruit cells for tissue regeneration. Whether coagulated blood yields a chemotactic gradient lacks experimental evidence, and should be investigated.

For AR or any other regenerative therapies to succeed in enabling post-operative tooth-root development in children and adolescents, tooth roots must undergo axial growth (lengthening), transverse growth (dentin-wall thickening) and convergence growth (apical closure) (Supplemental Movie 2). A lack of significant tooth-root lengthening in the present study is to our surprise and at variation with 52.8% self-reported root lengthening among the included 36 cases. The present finding of a lack of root-lengthening following AR is directly supported by absence of tooth-length increase among 34 trauma cases of immature permanent teeth by comparing AR with Apexification by cone-beam CT measurements37. Intuitively, root lengthening is necessary for apical closure. However, the present data only support root-dentin wall thickening, but not root lengthening, even in type III apical-closure cases. The average absolute tooth-root length increased by 1.2 millimeters in 18 months following AR29, perhaps too small to be clinically meaningful and may be susceptible to intrinsic measurement errors. A lack of significant tooth-root lengthening following AR is probably attributed to the observation that apical calcification bridge30, present in 47.2% of all included AR cases as the largest subgroup, may limit axial root lengthening. We speculate that apical calcification bridge (ACB) formation, perceived as a bridge in 2D radiographs, is actually a band of transverse mineralization in 3D, and may not develop into a pointy and closed apex. ACB differs from apical closure as a distinctive subgroup, as confirmed by a lack of root-dentin widening in the ACB subgroup but increased root-dentin area in the apical-closure subgroup. Post-operative root lengths in individual patients may indeed increase as shown in Case 3. However, a substantial root-length gain of AR-treated necrotic immature permanent teeth in children and adolescents as a population may not be a realistic expectation. Ratios of root lengths, apical widths and root-dentin areas were used in the present study to account for radiographic image distortion that is unavoidable among radiographs taken over time and by multiple practitioners31.

The present study is limited to the teaching of clinical cases included, in absence of any prospective and randomized clinical trial on AR’s efficacy. In experimental animal studies and several clinical case reports in which the teeth were extracted following AR, ingrowth of vascularized soft connective tissue was present in the treated root canal32,33. However, there is remarkable variation regarding the frequency, amount and nature of AR-induced tissue ingrowth32,34, potentially accounting for the diversity of types I, II and III outcome of the included clinical cases. Together, post-operative tooth-root development represents a general challenge to regenerate pediatric tissues that must grow to avoid organ defects21,22. Whether circulating blood activates local molecular cues to regenerate different and specific tissues warrant experimental and clinical investigations.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed, Scopus and Google-Scholar searches were performed using ((revascularization OR revitalization OR (regenerative endodontics) OR (regeneration)) AND (immature teeth) from inception of each database to September 15, 2016.

Study selection: PRISMA, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyse (PRISMA) was adhered in study selection (Fig. 1). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were pre-defined (Table 1). As in Fig. 1, cases were excluded, for example, because the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) or root apex was unrecognizable on radiographs despite independent effort made by at least four clinically qualified coauthors, and further verification by an oral and maxillofacial radiologist (S.J.Z.). Three coauthors independently screened the titles and abstracts of the 320 full-length studies without reviewing any data in each report’s Result section, and excluded 268 studies (Fig. 1) strictly based on the pre-defined exclusion criteria (Table 1) to yield the resulting 52 studies. Subsequently, three coauthors carefully read the full texts of the 52 full-length reports and further excluded 30 studies, with specific reasons stated in Results below (also c.f. Fig. 1).

Apical revascularization

The following generic AR treatments were representative among the included studies (Table 2). Following rubber-dam isolation, local anesthesia and tooth access preparation, necrotic root canals were disinfected using irrigants such as sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine at the first visit. Calcium hydroxide or antibiotic pastes were applied into the canals as inter-appointment medicaments (Table 2). At the second visit, root canals were cleaned with irrigants to remove the intracanal medicaments. Apical bleeding was induced by passing a hand instrument beyond the apical foramen to allow blood filling in the canal. Mineral trioxide aggregate was placed directly over the coagulated blood clot. The coronal access was sealed with permanent restorations.

Quantitative measurements of tooth-root development

To minimize potential bias, radiographs of all 36 cases were assigned to two clinically qualified coauthors with randomized and blinded radiograph sequence. Tooth-root development was quantified digitally on pre- and post-operative radiographs: root lengths as ratios of the treated and adjacent reference teeth, root-dentin geometry by subtracting root-canal area from tooth-root area, and apical closure as the ratio of crown and apical opening widths. The linear tooth-root length was measured independently by the two examiners from the CEJ to root apex digitally on all pre- and post-operative radiographs per existing methods31,35. To compensate for potential radiographic distortion with images taken over time and by multiple practitioners in the literature, the linear root length of not only the treated teeth (TT), but also the adjacent reference teeth (RT) were measured as long as the reference teeth had already completed root development31. TT/RT ratios were calculated not only to minimize radiographic image distortion, but also for cross-patient comparisons31. For immature permanent teeth with open apices, a linear line was drawn to connect apical tips with the center of the transverse line used as the apical end for root-length measurements31. Apical calcification bridge30 was measured as a transverse mineralization band that joined apical root tips30,31 blindly and independently by the two examiners. Root-dentin area was measured by subtracting root-canal area from the total root area that was defined from the apex to a transverse line connecting two CEJs36. Root-dentin area ratios were calculated by dividing root-dentin area against the total root area. Apical-width ratios were calculated by dividing apical-opening width against the width of a transverse line connecting the two CEJs per tooth. Apical radiolucency was stratified into four categories: −/−: no apical radiolucency before or after treatment; −/+: no apical radiolucency before treatment but detected apical radiolucency following treatment; +/+: apical radiolucency both before and after treatment; +/−: apical radiolucency before treatment but resolved following treatment.

Statistical analysis

Random effects approach was adopted in absence of consistent measure of tooth-root development among the included 22 studies. The meta-analysis investigated whether tooth-root length ratios, apical width ratios, and root area ratios had any significant change following AR using a linear mixed effects model where recall time was the main predictor, controlling for the value at baseline, and the type of the treated tooth (e.g. incisors vs. premolars) if it proved significant. Random effects were included in the model to account for variations among the included 22 studies. Nested random effects within each study were included to account for variations among subjects within each study, with additional random effects included to account for variations between the two independent examiners. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate the inter-examiner reliability of the three outcomes. We further investigated whether tooth-root length ratios, apical width ratios, and root area ratios differed significantly among the three subgroups of apical closure status by assessing the moderating effect of apical closure type. For any significant post-operative change, cutoff values were determined by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) method for apical closure prediction. All statistical analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.4, and plots were generated using R version 3.0.1. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

References

Selwitz, R. H., Ismail, A. I. & Pitts, N. B. Dental caries. Lancet 369, 51–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60031-2 (2007).

Shaw, J. H. Causes and control of dental caries. N Engl J Med 317, 996–1004, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198710153171605 (1987).

World Health Organization/Media Center/Fact sheet/Oral health/April 2012. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs318/en (2012).

Bruce A. Dye, Gina Thornton-Evans, Xianfen Li & Timothy J. Iafolla. NCHS Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db191.htm (2015).

Hintze, H. Approximal caries prevalence in Danish recruits and progression of caries in the late teens: a retrospective radiographic study. Caries Res 35, 27–35, 47427 (2001).

Hecova, H., Tzigkounakis, V., Merglova, V. & Netolicky, J. A retrospective study of 889 injured permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 26, 466–475, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-9657.2010.00924.x (2010).

2005-06 Survey of Dental Services Rendered. American Dental Association. American Dental Association Survey Center (2007).

Leinonen, M. & Saikku, P. Evidence for infectious agents in cardiovascular disease and atherosclerosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2, 11–17 (2002).

Slavkin, H. C. & Baum, B. J. Relationship of dental and oral pathology to systemic illness. JAMA 284, 1215–1217 (2000).

Trope, M. Treatment of the immature tooth with a non-vital pulp and apical periodontitis. Dent Clin North Am 54, 313–324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2009.12.006 (2010).

Dienstag, J. L. H. B virus infection. N Engl J Med 359, 1486–1500, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0801644 (2008).

Diogenes, A., Ruparel, N. B., Shiloah, Y. & Hargreaves, K. M. Regenerative endodontics: A way forward. J Am Dent Assoc 147, 372–380, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2016.01.009 (2016).

Louis, H. Berman, Kenneth, M. Hargreaves & Stephen Cohen. Pathways of the Pulp Expert Consult 10th Edition. (ed. Kenneth M.) 100–103 (St. Louis, MO, c2011).

Garcia-Godoy, F. & Murray, P. E. Recommendations for using regenerative endodontic procedures in permanent immature traumatized teeth. Dent Traumatol 28, 33–41, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.01044.x (2012).

Op Heij, D. G., Opdebeeck, H., van Steenberghe, D. & Quirynen, M. Age as compromising factor for implant insertion. Periodontol 2000 33, 172–184 (2003).

Ostby, B. N. The role of the blood clot in endodontic therapy. An experimental histologic study. Acta Odontol Scand 19, 324–353 (1961).

Law, A. S. Considerations for regeneration procedures. Pediatr Dent 35, 141–152 (2013).

Galler, K. M. et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: Revitalization procedures. Int Endod J 49, 717–723, https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12629 (2016).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. & Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339, b2535, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535 (2009).

Liberati, A. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62, e1–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 (2009).

Williams, C. & Guldberg, R. E. Tissue Engineering for Pediatric Applications. Tissue Eng Part A 22, 195–196, https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.TEA.2015.0514 (2016).

Elliott, M. J. et al. Stem-cell-based, tissue engineered tracheal replacement in a child: a 2-year follow-up study. Lancet 380, 994–1000, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60737-5 (2012).

Khasnis, S. A., Kidiyoor, K. H., Patil, A. B. & Kenganal, S. B. Vertical root fractures and their management. J Conserv Dent 17, 103–110, https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-0707.128034 (2014).

Camp, J. H. Diagnosis dilemmas in vital pulp therapy: treatment for the toothache is changing, especially in young, immature teeth. Pediatr Dent 30, 197–205 (2008).

Moorrees, C. F., Fanning, E. A. & Hunt, E. E. Jr. Formation and Resorption of Three Deciduous Teeth in Children. Am J Phys Anthropol 21, 205–213 (1963).

Dua, K. S., Hogan, W. J., Aadam, A. A. & Gasparri, M. In-vivo oesophageal regeneration in a human being by use of a non-biological scaffold and extracellular matrix. Lancet 388, 55–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01036-3 (2016).

de Vos, R. J. et al. Platelet-rich plasma injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 303, 144–149, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1986 (2010).

Alsousou, J., Thompson, M., Hulley, P., Noble, A. & Willett, K. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in trauma and orthopaedic surgery: a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91, 987–996, https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.22546 (2009).

Nagy, M. M., Tawfik, H. E., Hashem, A. A. & Abu-Seida, A. M. Regenerative potential of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulps after different regenerative protocols. J Endod 40, 192–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2013.10.027 (2014).

Shabahang, S. Treatment options: apexogenesis and apexification. J Endod 39, S26–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2012.11.046 (2013).

He, L. et al. Regenerative Endodontics by Cell Homing. Dent Clin North Am 61, 143–159, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2016.08.010 (2017).

Wang, X., Thibodeau, B., Trope, M., Lin, L. M. & Huang, G. T. Histologic characterization of regenerated tissues in canal space after the revitalization/revascularization procedure of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod 36, 56–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.039 (2010).

Shimizu, E., Jong, G., Partridge, N., Rosenberg, P. A. & Lin, L. M. Histologic observation of a human immature permanent tooth with irreversible pulpitis after revascularization/regeneration procedure. J Endod 38, 1293–1297, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2012.06.017 (2012).

Thibodeau, B., Teixeira, F., Yamauchi, M., Caplan, D. J. & Trope, M. Pulp revascularization of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod 33, 680–689, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2007.03.001 (2007).

Bose, R., Nummikoski, P. & Hargreaves, K. A retrospective evaluation of radiographic outcomes in immature teeth with necrotic root canal systems treated with regenerative endodontic procedures. J Endod 35, 1343–1349, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2009.06.021 (2009).

Flake, N. M., Gibbs, J. L., Diogenes, A., Hargreaves, K. M. & Khan, A. A. A standardized novel method to measure radiographic root changes after endodontic therapy in immature teeth. J Endod 40, 46–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2013.09.025 (2014).

Lin, J., Zeng, Q., Wei. X. et al. Regenerative Endodontics Versus Apexification in Immature Permanent Teeth with Apical Periodontitis: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. J Endod. pii: S0099-2399(17)30810-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2017.06.023 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all authors of the included 22 reports for their teaching. We apologize to anyone whose work may meet our defined inclusion criteria but may have been inadvertently excluded. We welcome any comments and dialogue on clinical efficacy of apical revascularization. We thank Dr. G. Hasselgren and Dr. C.S. Solomon for their helpful discussion on the manuscript. We thank J.M. Zheng for capturing our ideas in the included cartoon movies. We thank F. Guo, Y.W. Tse and P. Ralph-Birkett for their administrative assistance. The work is supported by NIH grants R01DE025643, R01DE023112, R01 AR065023 and R01DE026297 to J.J. Mao and Guangdong Pioneer Grant (52000-52010002) and Guangdong Science and Technology Program (2016B030229003), and International Cooperation Program of Ministry of Science and Technology (2014DFA31990) to L. Ye.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.H., J.Z., Q.M.G., B.C., J.Q.L. and J.J.M. designed the study. L.H., J.Z., Q.M.G., L.S.X., J.X.Z., Y.X.L. and C.Y.G. collected and analyzed the data. L.H., J.Z., Q.M.G. and B.C. analyzed the data. S.J.Z. provided suggestions radiographic methods. L.H., S.G.K., J.J.M. wrote the manuscript. L.Y., X.D.Z., and J.Q.L. provided critical input for the study and revised the manuscript. L.H., J.Z., Q.M.G. prepared Figures 1–4 and Tables 1–3. L.H., L.S.X., J.X.Z., Y.X.L. and C.Y.G. prepared supplemental materials. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, L., Zhong, J., Gong, Q. et al. Treatment of Necrotic Teeth by Apical Revascularization: Meta-analysis. Sci Rep 7, 13941 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14412-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14412-x

This article is cited by

-

Influence of photobiomodulation therapy on regenerative potential of non-vital mature permanent teeth in healthy canine dogs

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2025)

-

What is the best long-term treatment modality for immature permanent teeth with pulp necrosis and apical periodontitis?

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2021)

-

Effect of photobiomodulation therapy on regenerative endodontic procedures: a scoping review

Lasers in Dental Science (2019)