Abstract

The efficiency of X-ray-induced scintillation in glasses roughly depends on both the effective atomic number Zeff and the photoluminescence quantum efficiency Qeff of glass, which are useful tools for searching high-performance phosphors. Here, we demonstrate that the energy transfer from host to activators is also an important factor for attaining high scintillation efficiency in Ce-doped oxide glasses. The scintillation intensity of glasses with coexisting fractions of Ce3+ and Ce4+ species is found to be higher than that of a pure-Ce3+-containing glass with a lower Zeff value. Values of total attenuation of each sample indicate that there is a non-linear correlation between the scintillation intensity and the product of total attenuation and Qeff. The obtained results illustrate the difficulty in understanding the luminescence induced by ionizing radiation, including the energy absorption and subsequent energy transfer. Our findings may provide a new approach for synthesizing novel scintillators by tailoring the local structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phosphors are a kind of energy converters that generate light in a broad range of wavelengths from ultraviolet (UV) to infrared (IR). Although most phosphors possess the ability to convert light1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, some phosphors emit light as a result of mechanical stress36,37. Conventional phosphors are classified into two types: phosphors excited by UV or visible light2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 and phosphors excited by ionizing radiation21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. For the latter, the photon energy is far beyond the band gap of materials and radiation-induced luminescence is brought about by energy transfer from the host matrix to activators38,39,40,41. Therefore, X-ray-induced scintillation is a complex process involving absorption of X-rays in the matrix and scintillation in the activators. The absorption of X-rays by a material, i.e. the total attenuation of ionizing radiation, which can be expressed in terms of an absorption cross-section, is proportional to the density of the material, ρ, and the fourth-power of effective atomic number of the material, Zeff4,38,39. On the other hand, the scintillation efficiency, η, is typically expressed as η = βe-h·Strans·Qeff, where βe-h, Strans, and Qeff are the efficiencies of the processes for generating electron-hole pairs (generation of the secondary particles), transferring the energies of the secondary particles to luminescent centres, and exciting and emitting light at luminescent centres, respectively. The value of Qeff is conventionally referred to as the internal quantum efficiency of photoluminescence (PL). Generally, the development of scintillators mainly focuses on the values of Zeff and Qeff because it is difficult to discuss quantitatively the efficiencies for the electron-hole generation or energy transfer processes. This is the reason why most studies have been performed using lanthanide-doped garnet crystals.

On the other hand, our group has focused on amorphous materials. Owing to their wide chemical composition range and good formability, glasses can be good candidates for detection of ionizing radiation27,28,29. One of the glasses reported for phosphor applications is a Ce-doped lithium borosilicate glass27. Although this type of glass contains no heavy element, it is a good reference for the following reasons: (1) Since the glass can be prepared in an inert atmosphere, clear emission properties of Ce3+ are observed. (2) The Qeff values of the glasses are sufficiently high to discuss the changes of the scintillation efficiency. (3) Both B2O3 and SiO2 can make glass networks, which correlates with the energy absorption and transfer process to the activators. (4) Valence states of Ce can be quantitatively discussed by using X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) analyses due to the lack of heavy cations whose absorption regions may overlap. A change in the compositional fraction of B2O3 and SiO2 is equivalent to a change in the value of Zeff. Therefore, it is worthwhile to examine the PL and scintillation properties of Ce3+ in this glass system.

The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between the valence state of activators in the lithium borosilicate glasses possessing different Zeff values and the PL and scintillation efficiency. In order to discuss the valence state of cerium, the Ce3+ ratio in the glasses is introduced and defined as the ratio of the Ce3+concentration to the sum of the concentrations for Ce3+ and Ce4+. Based on several analytical data, we have found that there is an anomalous relationship between the scintillation properties and the chemical composition of glass.

Results

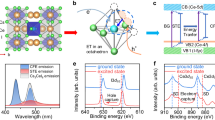

The chemical composition of the present glass system is xCe3+-40Li2O–yB2O3–(60-y)SiO2 (in molar ratio), where an excess amount of Ce is added. Herein, the general glass system is abbreviated as xCe:LBSy. First, we examined several Ce-doped Li2O-B2O3-SiO2 glasses in order to change the Zeff value. An increase in the amount of SiO2 increases the value of Zeff, which determines the effective absorption of X-ray energy. The chemical composition and the nominal Zeff values of these glasses are listed in Table S1. Figure 1(a) shows the optical absorption spectra of 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses at room temperature (RT) for different values of y. Comparison of the absorption spectra for 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses with those of non-doped LBSy glasses (Fig. 1(b)) demonstrates that most of the absorption is due to the addition of Ce. Furthermore, the shape of the spectra in Fig. 1(a) changes considerably with the value of y (i.e. the B2O3-SiO2 ratio). On the other hand, Fig. 1(c) shows that the shape of the spectra slightly changes with the value of x (i.e. the Ce concentration)27. As shown in the inset of Fig. 1(c), when the chemical composition of LBSy is fixed, the optical absorption edge is slightly red-shifted with increasing amounts of Ce3+ due to be a broadening of the tail, i.e. a local coordination change (see Fig. S1). However, as shown in the inset of Fig. 1(a), the absorption coefficient at the tail region is largely red-shifted with increasing SiO2 fractions. Therefore, it is expected that the absorption shape depends on both parameters x and y. Since the absorption tail of Ce4+ is observed at low energy regions28,29, it is assumed that the red-shift of the absorption tail is correlated with the generation of Ce4+ species. Clear absorption bands are observed for LBS30 and LBS40 glasses. After a peak deconvolution using six absorption peaks with a half-width at half-maximum of approximately 2250 cm−1, we found that the photon energy of each excitation peak is almost the same. The results suggest that the Ce3+ coordination is almost the same for both glasses and that the activators are dispersed homogenously in the glass matrix.

Optical absorption spectra of 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses. Optical absorption spectra of (a) 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses, (b) non-doped LBSy glasses and (c) xCe:LBS40 glasses. The insets in Fig. 1(a) and (c) show zoomed-in view of the spectra at the optical absorption edge of these glasses.

In order to examine the valence state, we measured Ce LIII-edge XANES spectra of 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses, as shown in Fig. 2(a). These white lines change with the B2O3-SiO2 ratio, especially near y = 10. The shape of the spectrum for the 0.5Ce:LBS40 glass is very similar to that of Ce(OCOCH3)3·H2O, as shown in Fig. S2, and noticeable differences for varying Ce concentrations are not observed (Fig. 2(b)). We can, therefore, conclude that the valence state of almost all (>95%) Ce centres in these LBS40 glasses are Ce3+ states, which is independent of the Ce concentration. Although precise fitting is difficult, the Ce3+ ratio of these glasses can be evaluated by spectra deconvolution using the spectra of Ce(OCOCH3)3·H2O and CeO2. Using these two reference materials, the Ce3+ ratios can be calculated as shown in Fig. 3. In the case of Ce:LBS30 and LBS40 glasses, the valence state of Ce is mostly the trivalent state. However, when the SiO2 fraction increases, the Ce3+ ratio decreases. It is notable that the XANES spectrum of the 0.5Ce:LBS10 glass is very similar to that of the 0.5Ce:LBS40 glass prepared in air (Fig S3), and that the Ce3+ ratio is less than 40 %, although the preparation of 0.5Ce:LBS10 was performed in an Ar atmosphere.

Figure 4 shows PL and PL excitation (PLE) spectra of 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses at RT. The wavenumbers of both the excitation and emission peaks of Ce3+ for the present glass are lower than those in phosphate glasses19,20 while higher than those in silicate glasses20. As the B2O3 fraction decreases, both peaks are slightly red-shifted, i.e. a smaller excitation energy induces a smaller emission energy. This might be correlated with the behaviour of the optical absorption spectra shown in Fig. 1(a), in which the absorption tail red-shifts with decreasing B2O3 fraction. Figure 5 shows contour plots of the PL-PLE spectra of 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses, where the PL intensity was normalized in order to understand the shapes of the spectra. The vertical and horizontal axes show the photon wavenumbers of excitation and emission, respectively. The fact that the excitation band is broad suggests that it is associated with the continuous excitation band, which is characteristic of Ce3+ states. However, as shown in Figs 4 and 5, the spectrum shape of the LBS10 glass is quite different from the shapes of the spectra for other B2O3 fractions. Irregularities associated with the LBS10 glass are also evident in the PL decay curves of xCe:LBSy glasses shown in Fig. 6(a) for different B2O3 fractions. Specifically, a clear deviation from the linearity of the decay curves is observed for a B2O3 fraction of y = 10 shown in Fig. 6(b) and Fig S4. The decay constants of xCe:LBSy glasses are summarized in Table S2. The internal quantum efficiencies Qeff of xCe:LBSy glasses are shown in Table S3 and Fig. 7. The values of Qeff roughly depend on the Ce concentration and variations of Qeff are probably due to differences in the local coordination state.

Figure 8(a) shows X-ray induced scintillation spectra of 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses obtained by and irradiation dose of 10 Gy. The scintillation intensities are normalized using the volume of the sample. We have confirmed that the scintillation spectra were unchanged during irradiation and that there is a linear relationship between the irradiation dose and the scintillation intensity (Fig. S5(a) and (b)). Figure 8(a) also shows that emission peak wavenumbers of Ce3+ red-shift with decreasing B2O3 fraction, as was observed in the PL spectra. It is noteworthy that the emission peak area of the 0.5Ce:LBS10 glass is much larger than that of the 0.5Ce:LBS40 glass, although we have confirmed that many Ce species are oxidized into Ce4+ during melting. In order to discuss the Ce3+ ratio quantitatively, the values of Qeff, and the scintillation peak area (normalized to the peak area of the 0.5Ce:LBS40 glass) are plotted in Fig. 8(b) as a function of Z eff (bottom axis) and the B2O3 fraction (upper axis). It is evident that the scintillation intensity is proportional to Zeff and inversely proportional to Qeff and the Ce3+ ratio.

Discussion

We have found that the chemical composition of glass affects the valence state of the activator in glasses. The results clearly suggest that the average Ce3+ ratio is affected by the chemical composition of glass, i.e. the macroscopic basicity of glass. In order to explain the results, we use the concept of the ‘optical basicity’ defined by Duffy42,43. Optical basicity, i.e. the average basicity of oxides in the glass, is a concept based on the polarization of electrons. The idea of basicity of glasses is sometimes useful for evaluation of the physical properties of bulk glasses. The optical basicity of Li2O, B2O3, and SiO2 are reported to be 1, 0.42, and 0.48, respectively43. Therefore, when the optical basicity of glass increases by substitution of SiO2 for B2O3, it is expected that an oxidation reaction of Ce3+ into Ce4+ occurs even in an Ar atmosphere. Since the starting materials of glass can affect the valence state of Ce cations29, it is not possible to reach a direct conclusion from the observed phenomena. However, an increase of the optical absorption in SiO2-rich glasses is expected to be brought about by a redox reaction transforming Ce3+ into Ce4+.

To the best of our knowledge, the physics of ionizing radiation is still unclear because of the complexity of the process. Therefore, research on scintillators is often conducted by focusing on specific parameters. Although Qeff is generally a useful parameter to develop scintillators, Zeff has been found to play a more dominant role for X-ray-induced scintillators34.

As mentioned above, an increase in the SiO2 fraction causes an increase of Zeff, which in turn increases the effective absorption of X-rays. Figure 9 shows the X-ray-induced scintillation peak area of xCe:LBSy glasses as a function of the product ρ·Zeff4. Since the dopant concentration is less than 2 mol%, the density of glass, ρ, shown in Table S444 can be used for the discussion. With the exception of Ce:LBS10 glasses, in which a decrease in scintillation intensity is observed due to the strong self-absorption in the visible region, the scintillation peak areas are roughly dependent on the Ce concentration. Although the value of Qeff for the 0.5Ce:LBS10 glass is much lower than that of the 0.5Ce:LBS40 glass because of the generation of Ce4+ species, the scintillation peak area of the 0.5Ce:LBS10 glass is higher than the peak areas of most 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses in Fig. S9.

X-ray-induced scintillation peak area of xCe:LBSy glasses as a function of ρ·Zeff4 for different B2O3 fractions.

Figure 10(a) shows the total attenuation with coherent scattering of 0.5Ce:LBSy glasses, which was calculated using a previously published fomula45 that takes into account the influence of Zeff. The energy spectrum of the X-rays used in the present study46,47,48 is also shown in the figure with a scale given on the right axis. Here, the X-ray source is a conventional X-ray tube with a W target and a Be window. In the energy region of irradiated X-rays, the total attenuation of the 0.5Ce:LBS10 glass is the highest among the present samples. Moreover, the attenuation values without coherent scattering exhibit a similar tendency. Here, we determined the total absorption energy using the following expression:

where ζ is the absorbed energy in the sample along the irradiation axis per unit area, E is the incident radiation energy, N0 is the number of incident photons per unit area, μT(E) is the total attenuation coefficient of the sample, μ EA is the energy absorption coefficient of sample, and t is the thickness of the sample.

Figure 10(b) shows the total absorption energy, ζrelative, relative to that of the 0.5Ce:LBS10 glass. In the present X-ray energy region, the value of ζ for the 0.5Ce:LBS10 glass is approximately 1.2 times larger than that of the 0.5Ce:LBS40 glass. As mentioned above, the scintillation intensity Iscinti is a product of the total absorption energy ζ and the scintillation efficiency η = βe-h·Strans·Qeff and is given by

Since we have no quantitative information about the values of βe-h and Strans, their product, (βe-h . Strans), is treated as a coefficient that can be evaluated using Iscinti, ζrelative, and Qeff, and represents the efficiency for generating electron-hole pairs followed by energy transfer to luminescent centres in each glass. Using the values depicted in Figs 3(b) and 4(b), we have found that the value of (βe-h . Strans) for the 0.5Ce:LBS10 glass is more than 14 times larger than that of the 0.5Ce:LBS40 glass (see right axis of Fig. 4(b)). In other words, the absorbed X-ray energy is not converted into scintillation photons effectively in 0.5Ce:LBS40 glasses.

Plausible reasons for the low conversion efficiency are the physical parameters of non-doped LBS glasses shown in Table S444. Since the molar volume of the LBS10 glass is smaller than that of the LBS40 glass, the network of the LBS10 glass is spatially denser than that of the LBS40 glass, i.e. there is larger free volume in the LBS40 glass. If there is no large difference in the phonon vibration energies of LBSy glasses, the free volume in the glasses may work as an attenuator and inhibit the effective energy transfer to activators. On the other hand, another reason for the low conversion efficiency is the storage mechanism of irradiated energy proposed by Yanagida34. It was reported that a B2O3-containing glass exhibits storage luminescence by X-ray irradiation35. Because the irradiated energy is converted into scintillation, storage luminescence, or thermal vibration (non-radiative relaxation), high storage luminescence means low scintillation. Considering that the origin of storage luminescence is defects in glasses, we speculate that there are many defects that affect the energy transfer process to activators in B2O3-rich glass. As shown in Fig. S6 and Table S5, there are only small differences in the band gaps for LBSy glasses and these differences cannot provide a plausible explanation for changes in the conversion efficiencies.

Recent studies have suggested that the fraction of Ce4+ in scintillators has an effect on scintillation properties49,50,51,52 and several of them claimed that coexistence of Ce3+ and Ce4+ is important for high scintillation efficiency49,50,51. However, if the coexistence of Ce3+ and Ce4+ was a critical factor for determining the intensity, the correlation between chemical composition and scintillation intensity, as shown in Fig. 3(a), would be quite different; i.e. Ce:LBSy glasses would exhibit similar intensities with the exception of the Ce:LBS10 glass. Therefore, the present results do not support the hypothesis that coexistence of Ce3+ and Ce4+ is important for high scintillation efficiency, at least in the present glass system. In turn, this work shows that the energy transfer process of the generated charged secondary particles to activators is important for attaining high scintillation efficiency. Therefore, tailoring the energy transfer process is expected to enable fabrication of high-performance scintillators.

Conclusion

We have examined PL and X-ray-induced scintillation properties of several Ce-doped lithium borosilicate glasses. It was confirmed that only Ce3+ valence states exist in Ce:LBS40 glasses and that the Ce3+ ratio decreases with increasing SiO2 fraction in the glasses. The oxidation reaction in the glass melt in an inert atmosphere can be explained by the optical basicity of the glass, and the amount of Ce4+ generated is the origin of the absorption tail in the visible region of the absorption spectra. Although the value of Qeff for the Ce:LBS10 glass is the smallest among all Qeff values for the present LBS glasses, the scintillation intensity of the Ce:LBS10 glass is the highest because it has the highest attenuation values. In terms of the emission mechanism of scintillators, the effective energy conversion after absorbing the ionizing radiation is prevented in the B2O3-rich glasses. Such energy transfer path will be important for further materials design of radiation detectors.

Methods

Preparation of Ce-doped lithium borosilicate glass

The xCe3+-40Li2O–xB2O3–(60-y)SiO2 (xCe:LBSy) glasses were prepared according to a conventional melt-quenching method by employing a platinum crucible24. A mixture of Li2CO3 (99.99%), B2O3 (99.9%), SiO2 (99.999%), and Ce(OCOCH3)3·2H2O (99.9%) was melted in an electric furnace at 1100°C for 30 min in an Ar atmosphere (99.999%). The glass melt was quenched on a stainless plate at 200°C and then annealed at a temperature Tg, which was measured by differential thermal analysis (DTA) for 1 h. The bulk glasses were cut into several glass pieces (10 mm × 10 mm) using a cutting machine, and then, samples were mechanically polished (thickness ~ 1 mm) to obtain mirror surfaces. The temperature Tg was determined by a DTA system operating at a heating rate of 10 °C/min using a TG8120 instrument (Rigaku, Japan). The density of the samples was measured using the Archimedes method with pure water as an immersion liquid.

Luminescence properties

The PL and PLE spectra were recorded at 1 nm intervals at RT using an F7000 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Tech. Japan). Band pass filters of 2.5 nm for the PL measurement were used for both excitation and emission. The absorption spectra at RT were recorded at 1 nm intervals using a U3500 UV-vis-NIR spectrometer (Hitachi High-Tech. Japan). The absolute quantum efficiencies, also known as quantum yields (QYs), of the glasses were measured using an integrating sphere Quantaurus-QY (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). The error bars were ±2. The emission decay at RT was measured using a Quantaurus-Tau system (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) with a 340 nm LED. The accumulated counts for evaluation were 50,000. Scintillation (radioluminescence) spectra were measured by using a CCD-based spectrometer (Andor DU920P CCD and SR163 monochromator) under X-ray exposure23. The supplied bias voltage and tube current were 40 kV and 0.52 ~ 5.2 mA, respectively.

XANES measurement

The Ce LIII-edge XANES spectra were measured at the BL01B1 and BL14B2 beamlines of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan). The storage ring energy was operated at 8 GeV with a typical current of 100 mA. The measurements were performed using a Si (111) double-crystal monochromator in the transmission mode (Quick Scan method), or in the fluorescence mode using 19-SSD detector at RT. The XANES spectra were recorded from 5.52 to 6.18 keV. Pellet samples for the measurements were prepared by mixing the granular sample with boron nitride. As references, XANES data for Ce(OCOCH3)3·2H2O and CeO2 were collected using the same conditions. The corresponding analyses were performed by using Athena software53.

References

Yen, W. M., Shionoya, S. & Yamamoto, H. Phosphor Handbook 2nd Edition (CRC Press, 2007).

Blasse, G. & Bril, A. Investigation of some Ce3+-activated phosphors. J. Chem. Phys. 47, 5139–5145 (1967).

Bachmann, V., Ronda, C. & Meijerink, A. Temperature quenching of yellow Ce3+ luminescence in YAG:Ce. Chem. Mater. 10, 2077–2084 (2009).

Pollnau, M., Gamelin, D. R., Luthi, S. R., Gudel, H. U. & Hehlen, M. P. Power dependence of upconversion luminescence in lanthanide and transition-metal-ion systems. Phys. Rev. B 61, 3337–3346 (2000).

Blasse, G. & Bril, A. Study of energy transfer from Sb3+, Bi3+, Ce3+ to Sm3+, Eu3+, Tb3+, Dy3+. J. Chem. Phys. 47, 1920–1926 (1967).

Matsuzawa, T., Aoki, Y., Takeuchi, N. & Murayama, Y. New long phosphorescent phosphor with high brightness, SrAl2O4:Eu2+,Dy3+. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 2670–2673 (1996).

Xie, R. J. & Hirosaki, N. Silicon-based oxynitride and nitride phosphors for white LEDs - A review. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 8, 588–600 (2007).

Reisfeld, R. Spectra and energy transfer of rare earths in inorganic glasses. Structure and Bonding 13, 53–98 (1973).

Layne, C. B., Lowdermilk, W. H. & Weber, M. J. Multiphonon relaxation of rare-earth ions in oxide glasses. Phys. Rev. B. 16, 10–20 (1977).

Shinn, M. D., Sibley, W. A., Drexhage, M. G. & Brown, R. N. Optical-transitions of Er3+ ions in fluorozirconate glass. Phys. Rev. B 27, 6635–6648 (1983).

Schreiber, H. D. et al. Compositional dependence of redox equilibria in sodium-silicate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 177, 340–346 (1994).

Duffy, J. A. & Kyd, G. O. Ultraviolet absorption and fluorescence spectra of cerium and the effect of glass composition. Phys. Chem. Glass 37, 45–48 (1996).

Skuja, L. Optically active oxygen-deficiency-related centers in amorphous silicon dioxide. J. Non-Crystal. Solids 239, 16–48 (1998).

Ebendorff-Heidepriem, H. & Ehrt, D. Formation and UV absorption of cerium, europium and terbium ions in different valencies in glasses. Opt. Mater. 15, 7–25 (2000).

Paulose, P. I., Jose, G., Thomas, V., Unnikrishnan, N. V. & Warrier, M. K. R. Sensitized fluorescence of Ce3+/Mn2+ system in phosphate glass. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 64, 841–846 (2003).

Caldino, U., Hernandez-Pozos, J. L., Flores, C., Speghini, A. & Bettinelli, M. Photoluminescence of Ce3+ and Mn2+ in zinc metaphosphate glasses. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 17, 7297–7305 (2005).

Murata, T., Sato, M., Yoshida, H. & Morinaga, K. Compositional dependence of ultraviolet fluorescence intensity of Ce3+ in silicate, borate, and phosphate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 351, 312–316 (2005).

Bei, J. F. et al. Optical properties of Ce3+-doped oxide glasses and correlations with optical basicity. Mater. Res. Bull. 42, 1195–1200 (2007).

Masai, H., Takahashi, Y., Fujiwara, T., Matsumoto, S. & Yoko, T. High photoluminescent property of low-melting Sn-doped phosphate glass. Appl. Phys. Express 3, 082102 (2010).

Masai, H. et al. Correlation between preparation conditions and the photoluminescence properties of Sn2+ centers in ZnO-P2O5 glasses. J. Mater. Chem. C 2, 2137–2143 (2014).

Combes, C. M., Dorenbos, P., van Eijk, C. W. E., Krämer, K. W. & Güdel, H. U. Optical and scintillation properties of pure and Ce3+-doped Cs2LiYCl6 and Li3YCl6: Ce3+ crystals. J. Lumin. 82, 299–305 (1999).

Dorendos, P. et al. 4f-5d spectroscopy of Ce3+ in CaBPO5, LiCaPO4 and Li2CaSiO4. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 15, 511–520 (2003).

Yanagida, T., Kamada, K., Fujimoto, Y., Yagi, H. & Yanagitani, T. Comparative study of ceramic and single crystal Ce:GAGG scintillator. Opt. Mater. 35, 2480–2485 (2013).

Masai, H. & Yanagida, T. Emission property of Ce3+-doped Li2O-B2O3-SiO2 glasses. Opt. Mater. Express 5, 1851–1858 (2015).

Yanagida, T., Ueda, J., Masai, H., Fujimoto, Y. & Tanabe, S. Optical and scintillation properties of Ce-doped 34Li2O-5MgO-10Al2O3-51SiO2 glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 431, 140–144 (2016).

Torimoto, A. et al. Emission properties of Ce3+ centers in barium borate glasses prepared from different precursor materials. Opt. Mater. 72, 52–57 (2017).

van Eijk, C. W. E., Bessiére, A. & Dorenbos, P. Inorganic thermal-neutron scintillators. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 529, 260–267 (2004).

Kouzes, R. T. et al. Neutron detection alternatives to 3He for national security applications. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 623, 1035–1045 (2010).

Iwanowska, J. et al. Thermal neutron detection properties with Ce3+ doped LiCaAlF6 single crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 652, 319–322 (2011).

Mizukami, K. et al. Measurements of performance of a pixel-type two-dimensional position sensitive Li-glass neutron. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 529, 310–312 (2004).

Ishii, M. et al. Boron based oxide scintillation glass for neutron detection. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 537, 282–285 (2005).

Masai, H. et al. Local coordination state of rare earth in eutectic scintillators for neutron detector applications. Sci. Rep. 5, 13332 (2015).

Torimoto, A. et al. Emission properties of Ce-doped alkaline earth borate glasses for scintillator applications. Opt. Mater. 73, 517–522 (2017).

Yanagida, T. Ionizing radiation induced emission: Scintillation and storage-type luminescence. J. Lumin. 169, 544–548 (2016).

Nanto, H. et al. Optically stimulated luminescence in x-ray irradiated xSnO–(25-x)SrO–75B2O3 glass. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 784, 14–16 (2015).

Atari, N. A. Piezoluminescence phenomenon. Phys. Lett. 90A, 93–96 (1982).

Xu, C. N., Watanabe, T., Akiyama, M. & Zheng, X. G. Artificial skin to sense mechanical stress by visible light emission. Appl. Phys. Lett. 74, 1236–1238 (1999).

Jackson, D. F. & Hawkes, D. J. X-ray attenuation coefficients of elements and mixtures. Phys. Reports 70, 169–233 (1981).

Knoll, G. F. Radiation Detection and Measurement, Fourth Edition, John Wiley & Sons (2012).

Robbins, D. J. On predicting the maximum efficiency of phosphor systems excited by ionizing radiation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 127, 2694–2702 (1980).

Lempicki, A., Wojtowicz, A. J. & Berman, E. Fundamental limits of scintillator performance. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 333, 304–311 (1993).

Duffy, J. A. & Ingram, M. D. An interpretation of glass chemistry in terms of the optical basicity concept. J. Non-Crystal. Solids 21, 373–410 (1976).

Duffy, J. A. A review of optical basicity and its applications to oxidic systems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 57, 3961–3970 (1993).

Masai, H., Matsumoto, S., Ueda, Y. & Koreeda, A. Correlation between valence state of tin and elastic modulus of Sn-doped Li2O–B2O3–SiO2 glasses. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 185104 (2016).

Boone, J. M., Fewell, T. R. & Jennings, R. J. Molybdenum, rhodium, and tungsten anode spectral models using interpolating polynomials with application to mammography. Med. Phys. 24, 1883–1874 (1997).

Boone, J. M. & Seibert, J. A. An accurate method for computer-generating tungsten anode x-ray spectra from 30 to 140 kV. Med. Phys. 24, 1661–1670 (1997).

Fewell, T. R., Shuping, R.E. & Healy, K. Handbook of Computed Tomography X-ray Spectra; HHS Publication (FDA) 81-8162. (Rockville, MD, 1981).

Wu, Y. T., Meng, F., Li, Q., Koschan, M. & Melcher, C. L. Role of Ce4+ in the scintillation mechanism of codoped Gd3Ga3Al2O12∶Ce. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2, 044009 (2014).

Zavartsev, Y. D., Koutovoi, S. A. & Zagumennyi, A. I. Czochralski growth and characterisation of large Ce3+:Lu2SiO5 single crystals co-doped with Mg2+ or Ca2+ or Tb3+ for scintillators. J. Crystal Growth. 275, e2167–e2171 (2005).

Nikl., M. et al. The stable Ce4+ center: A new tool to optimize Ce-doped oxide scintillators. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 63, 433–438 (2016).

Mansuy, C., Nedelec, J. M. & Mahiou, R. Molecular design of inorganic scintillators: from alkoxides to scintillating materials. J. Mater. Chem. 14, 3274–3280 (2004).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) Number 26709048, and the Collaborative Research Program of I.C.R., Kyoto University (grants #2015-40 and #2016-83). The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at the BL14B2 of SPring-8 with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) (Proposal Nos. 2015B1587, 2016A0130, 2016B0130, 2017A0130, and 2017B0130).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M. formulated the research project. H.M. and T.U. performed the materials preparation. H.M. and A.T. performed the XANES analysis. H.M., G.O., N.K. and T.Y. measured the X-ray-induced scintillation. H.M. and G.O. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Masai, H., Okada, G., Torimoto, A. et al. X-ray-induced Scintillation Governed by Energy Transfer Process in Glasses. Sci Rep 8, 623 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18954-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18954-y