Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) is an established biomarker of adverse outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Several cross-sectional studies have suggested a possible association between FGF23 and anemia in these patients. In this large-scale prospective cohort study, we investigated this relationship and examined whether high FGF23 levels increase the risk of incident anemia. This prospective longitudinal study included 2,089 patients from the KoreaN cohort study for Outcome in patients With CKD. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin level <13.0 g/dl (men) and <12.0 g/dl (women). Log-transformed FGF23 significantly correlated with hepcidin but inversely correlated with iron profiles and hemoglobin. Multivariate logistic regression showed that log-transformed FGF23 was independently associated with anemia (odds ratio [OR], 1.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04–1.24, P = 0.01). Among 1,164 patients without anemia at baseline, 295 (25.3%) developed anemia during a median follow-up of 21 months. In fully adjusted multivariable Cox models, the risk of anemia development was significantly higher in the third (hazard ratio [HR], 1.66; 95% CI, 1.11–2.47; P = 0.01) and fourth (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.23–2.76; P = 0.001) than in the first FGF23 quartile. In conclusion, high serum FGF23 levels were associated with an increased risk for anemia in patients with nondialysis CKD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anemia is one of the most common complications in chronic kidney disease (CKD), and its prevalence increases progressively as kidney function declines1. The recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported that anemia was twice as prevalent in persons with CKD (15.4%) as that in the general population (7.6%) in the United States2. In addition, anemia is closely associated with poor quality of life and adverse outcomes such as left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiovascular events, and increased mortality in patients with CKD3,4,5. Although the mechanism for anemia in CKD is primarily due to failure of erythropoietin (EPO) production in response to decreased hemoglobin concentration6, other potential factors such as chronic inflammation, iron deficiency, malnutrition, increased destruction of red blood cells, and vitamin D deficiency also contribute to the pathogenesis of renal anemia7,8,9.

Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23) is a bone-derived hormone that is crucial for maintaining normal phosphate and vitamin D homeostasis10,11. FGF23 levels increase gradually with diminishing renal function, and it seems to be an adaptive mechanism to prevent hyperphosphatemia12. Recently, elevated FGF23 levels have been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes, such as progression of kidney disease13,14, vascular calcification15, left ventricular hypertrophy16, cardiovascular events17,18, and increased mortality14,17,19. Considering that FGF23 and anemia are nontraditional risk factors for adverse outcomes in patients with CKD, and both are reciprocally changed according to kidney function, it would be intriguing to explore the relationship between FGF23 and anemia in CKD. Interestingly, the inhibitory effect of FGF23 on erythropoiesis was demonstrated in an experimental study20. However, only few human studies have suggested a possible association between FGF23 and anemia in patients with CKD21,22,23. In most studies, the causality between FGF23 and anemia could not be explained because this relationship was analyzed through a cross-sectional approach. The purpose of this study was, therefore, to further clarify the relationship between FGF23 levels and anemia in patients with CKD and to examine whether high FGF23 levels increase the future development of anemia, in a large-scale prospective cohort study.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

The KoreaN cohort study for Outcome in patients With Chronic Kidney Disease (KNOW-CKD) is a prospective nationwide cohort study investigating various clinical courses and risk factors for the progression of CKD in Korean patients. Patients aged between 20 and 75 years with CKD stage 1–5 before dialysis who voluntarily provided informed consent were enrolled from nine university-affiliated tertiary-care hospitals throughout Korea between June 2011 and February 2015. The detailed design and method of the study have previously been described elsewhere (NCT01630486 at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov)24. Among 2,238 patients in the KNOW-CKD cohort, 149 patients with missing data for hemoglobin, hepcidin, iron profiles, and C-terminal FGF23 (FGF23) levels were excluded. Finally, 2,089 patients were included in the present analysis (Fig. 1).

Data collection

Baseline sociodemographic information and laboratory data were obtained from the KNOW-CKD database. The resting blood pressure (BP) in the clinic was measured with an electronic sphygmomanometer, and body mass index (BMI) was determined using the formula “weight (kg)/height (m2). Serum sample collected for initial study measurements sent to the central laboratory of the KNOW-CKD study (Lab Genomics, Seongnam, Republic of Korea) and were stored at −80 °C in deep freezer. Along with blood samples, urine samples were also immediately sent to central lab and subject for proteinuria measurement. Laboratory tests were obtained every 6 months in the first year and then annually thereafter. Serum creatinine was measured using an isotope dilution mass spectrometry-traceable method, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation25. Serum levels of hepcidin were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (DRG Instruments GmBH, Marburg, Germany). Anemia was defined as hemoglobin levels of <13.0 g/dL for men and <12.0 g/dL for women according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. Transferrin saturation (TSAT) was calculated using the ratio of serum iron and total iron-binding capacity. Iron deficiency was defined as ferritin <100 ng/mL or TSAT <20%.

Serum C-terminal FGF23 concentration was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Immutopics, San Clemente, CA, USA). Regarding sensitivity of FGF23 assay, the 95% confidence limit on 20 duplicate determinations of the 0 RU/ml standard is 1.5 RU/ml. Precision of FGF23 assay was carried out for quality control measures. Intra-assay precision was calculated from 20 duplicate determinations of two samples each performed in a single assay. Coefficient of variations for FGF level of 33.7 and 302 RU/ml were 2.4% and 1.4%, respectively. In addition, inter-assay precision was calculated from duplicate determinations of two samples performed in 10 assays. Coefficient of variations for FGF level of 33.6 and 293 RU/mL were 4.7% and 2.4%, respectively.

Study endpoint

We first performed a cross-sectional analysis to clarify the relationship between serum FGF23 levels and anemia in 2,089 patients using the baseline data. Then, we further examined whether elevated FGF23 levels increase the future development of anemia in 1,164 patients who had no anemia at baseline (Fig. 1). For this analysis, the primary outcome was newly developed anemia during the follow-up period.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All variables with a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. If data did not have a normal distribution, they were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as number and proportion. Comparisons were made using one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables, as required. Pearson’s correlation test was used to evaluate the relationship between covariables, and a multivariable linear regression analysis for hemoglobin level was performed after adjustment for age, sex, presence of diabetes mellitus (DM), BMI, systolic BP (SBP), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), smoking status, eGFR, albumin, phosphorus, 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D, presence of iron deficiency, hepcidin, C-reactive protein (CRP), proteinuria, and anemia treatment including iron replacement and EPO-stimulating agent (ESA). In addition, a multivariable-adjusted logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine whether FGF23 was associated with anemia as defined based on WHO criteria. The results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Among 1,164 patients without baseline anemia, the cumulative anemia-free survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and differences between survival curves were compared with the log-rank test. Furthermore, multivariate Cox regression models for the development of anemia were constructed after rigorous and stepwise adjustments for confounding factors. Model 1 was the unadjusted model with no covariables. Model 2 included adjustment for age, sex, DM, BMI, SBP, CCI, and smoking. We constructed model 3 by adding eGFR, albumin, phosphorus, 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D, presence of iron deficiency, hepcidin, CRP, and proteinuria to model 2. Moreover, model 4 included iron replacement and ESA therapy in addition to model 3 variables. The results were presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. We also examined the association between FGF23 levels and the development of anemia through subgroup analysis using a fully adjusted multivariate Cox regression model. The patients were stratified according to sex, history of DM, presence of iron deficiency, treatment with renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, and median values of age, SBP, BMI, CCI, eGFR, albumin, CRP, and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Ethics statement

We carried out the study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the institutional review board of each participating clinical center, as follows: Seoul National University Hospital (1104–089–359), Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-1106/129-008), Yonsei University Severance Hospital (4-2011-0163), Kangbuk Samsung Medical Center (2011-01-076), Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (KC11OIMI0441), Gil Hospital (GIRBA2553), Eulji General Hospital (201105-01), Chonnam National University Hospital (CNUH-2011-092), and Pusan Paik Hospital (11-091) in 2011.

Results

Patient characteristics according to fibroblast growth factor-23

The median serum FGF23 level was 19.6 RU/ml. The median value of FGF23 in each quartiles, from the first to the fourth, was 0.0 (IQR, 0.0–0.4; range, 0.0–1.7), 9.5 (IQR, 4.8–15.9; range, 1.8–19.6), 25.5 (IQR, 22.3–29.8; range, 19.7–34.6), and 52.9 (IQR, 41.3–75.3; range, 34.7–774.0). According to FGF23 quartiles, we categorized the study subjects into four groups and compared their baseline characteristics (Table 1). The mean age was 53.6 ± 12.2 years and 1,275 patients (61.0%) were male. The mean eGFR was 50.3 ± 30.2 mL·min−1·1.73 m−2 and was significantly lower in high FGF23 quartiles than in low quartiles (P < 0.001). The prevalence of DM and serum levels of hepcidin, phosphorus, and intact parathyroid hormone were higher, whereas calcium and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D levels were lower in high FGF23 quartiles (P < 0.001 for all). The mean hemoglobin levels were 12.8 ± 2.0 g/dL and were significantly lower in high FGF23 quartiles (P < 0.001). Regarding iron profiles, serum iron levels and TSAT were also lower in high FGF23 quartiles. However, serum ferritin levels did not differ among quartiles. There were more patients who received iron replacement and ESA therapy in the high FGF23 quartiles.

Relationship between fibroblast growth factor-23 levels and baseline anemia

In Pearson correlation analyses, log-transformed FGF23 was inversely correlated with eGFR, albumin, calcium, 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D, iron, TSAT, and hemoglobin (Fig. 2), whereas it was positively correlated with CCI, phosphorus, intact parathyroid hormone, hepcidin, and proteinuria. However, age, BMI, CRP, and ferritin were not correlated with FGF23. We then performed in-depth analyses to clarify the association between FGF23 and anemia. In a multivariable linear regression analysis adjusted for confounding factors, there was a significant inverse relationship between log-transformed FGF23 and hemoglobin levels (β = −0.067, P = 0.004; Table 2). This finding was further strengthened in a multivariable logistic model (Table 3). After rigorous adjustment of confounders, log-transformed FGF23 was independently associated with anemia (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.04–1.24, P = 0.01). When FGF23 quartiles were entered as a categorical variable in the model, the highest quartile of FGF23 was significantly associated with anemia compared with the lowest quartile (OR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.19–2.50, P = 0.004).

High fibroblast growth factor-23 levels increase the development of anemia

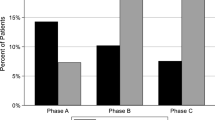

We further investigated whether FGF23 levels increase the future development of anemia. To this end, we selected 1,164 patients without anemia at baseline measurement. During the median follow-up duration of 21 (IQR, 7–38) months, 295 (25.3%) patients developed anemia. Anemia occurred in 48 (16.5%), 63 (21.6%), 91 (31.3%), and 93 (32.0%) patients in the first, second, third, and fourth quartile of FGF23, respectively (P < 0.001, Table 4). The Kaplan–Meier curves for anemia-free survival according to FGF23 quartiles are presented in Fig. 3. The time to the development of anemia was significantly shorter in high FGF23 quartiles (P = 0.009 for first vs. second; P < 0.001 for first vs. third and fourth). An in-depth analysis on the association between FGF23 levels and the development of anemia was performed using multivariable Cox regression models (Table 5). The crude HRs for incident anemia were 1.65 (95% CI, 1.13–2.40; P = 0.009), 2.55 (95% CI, 1.80–3.62; P < 0.001), and 2.94 (95% CI, 2.07–4.17; P < 0.001) in the second, third, and fourth quartile compared with the first quartile. Further stepwise multivariable adjusted models yielded similar results. In the fully adjusted model, the risk of developing anemia was significantly higher in the third (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.11–2.47; P = 0.01) and fourth (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.23–2.76; P = 0.003) quartile of FGF23 compared with the first quartile. When FGF23 was treated as a continuous variable, a significant association between FGF23 and anemia remained unaltered (HR for every 1 log increase, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.07–1.29; P = 0.001).

Subgroup analyses

We also investigated the relationship between FGF23 and the development of anemia in several subgroups stratified by age, sex, presence of diabetes, SBP, BMI, CCI, eGFR, albumin, 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D, CRP, and iron deficiency status. The results showed the consistent direction of the impact of FGF23 with respect to anemia in most stratified groups (Fig. 4). Notably, this association was observed particularly in nondiabetics, patients aged <50 years, patients treated with RAS blockers, patients with iron deficiency, or patients with SBP <130, BMI <25 kg/m2, CCI <3, eGFR >30 ml·min−1·1.73 m−2 or albumin ≥ 4.3 g/dl.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we demonstrated the inverse relationship between serum FGF23 and hemoglobin in patients with nondialysis CKD. In addition, we also showed that high serum FGF23 levels were significantly associated with an increased risk for the development of anemia even after a rigorous adjustment for multiple confounding factors. This association was particularly evident in patients treated with RAS blockers, patients with young age, relatively preserved eGFR, low comorbid burden, and iron deficiency. Our findings are of great clinical importance, as anemia is a frequent complication in patients with CKD and is associated with adverse outcomes3,4,5. Although there are well-established risk factors for anemia, our study suggests that FGF23 can also be a useful biomarker of incident anemia in patients with nondialysis CKD.

Studies that have evaluated the relationship between FGF23 and anemia have yielded conflicting results. To date, there have been only five studies that have specifically addressed this issue. In a study by Akalin et al., there was no association between FGF23 and hemoglobin levels in 89 patients undergoing hemodialysis26. In addition, a recent observational study by Honda et al. showed no significant relationship between FGF23 and hemoglobin levels in 282 patients undergoing hemodialysis27. These findings were contradicted by two other studies: one on patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis and one on patients with CKD before dialysis treatment21,22. These studies showed a significant inverse association between FGF23 and anemia. However, these studies are limited by their small sample size and cross-sectional analyses. Furthermore, as dialysis patients are more likely to receive iron preparation and ESA, interpretation should be made carefully in these patients. Of note, our study has a larger sample size than most previous studies, which thus assures power to detect statistical significance. In addition, we demonstrated that high FGF23 level increased the future development of anemia in a longitudinal observation of a CKD cohort. Our findings particularly corroborated findings from a recent publication by the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study investigators23, indicating that elevated FGF23 is associated with prevalent anemia, change in hemoglobin over time, and the development of anemia.

The mechanism responsible for FGF23-associated anemia is unknown. Although anemia in CKD is a multifactorial disorder, it is well explained by insufficient EPO, a hormone that stimulates red blood cell production in the bone marrow in response to low oxygen levels in the blood6,8. EPO production is impaired at any given hematocrit concentration in patients with decreased renal function6. Interestingly, one experimental study found that loss of FGF23 resulted in markedly augmented erythropoiesis in peripheral blood and bone marrow of young adult mice, which can be accounted for by elevated serum EPO levels and EPO mRNA synthesis in the bone marrow, liver, and kidney20. Conversely, in this study, administration of FGF23 in wild-type mice resulted in a decrease in erythropoiesis20. These experimental evidence together with clinical research studies including ours suggest that FGF23 is a negative regulator of erythropoiesis. Unfortunately, a correlation between FGF23 and EPO could not be determined in our study because the EPO levels were not measured. Future studies are required to clarify the relationship between FGF23 and EPO.

Vitamin D deficiency has been suggested as a risk factor for anemia in patients with CKD. Previous studies from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and Study to Evaluate Early Kidney Disease demonstrated that vitamin D deficiency was independently associated with anemia in patients with CKD9,28. Several studies using a burst-forming unit-erythroid assay have suggested a direct effect of vitamin D on proliferation of erythroid precursor cells obtained from patients with CKD, with a synergistic effect with EPO29,30,31. In addition, vitamin D deficiency is associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism, which can induce bone marrow fibrosis and suppress erythropoiesis in CKD32. Considering the fact that FGF23 decreases 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels by inhibiting CYP27B1 (1-α-hydroxylase) and by stimulating CYP24A1 (24-hydroxylase)10,11, vitamin D deficiency may be a potential mechanistic link that can explain the relationship between FGF23 and anemia. In this study, however, the effect of FGF23 on the development of anemia was not altered after adjustment for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels. Moreover, there was no significant interaction between FGF23-related anemia and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels in subgroup analysis. These findings indirectly support the result from the aforementioned experimental study, in which abolishing vitamin D signaling from FGF23 null mice did not resolve the erythropoietic abnormalities20.

It is well known that iron deficiency is an important factor that can promote anemia in CKD. Interestingly, animal and human studies demonstrated that absolute and functional iron deficiency stimulates FGF23 production33,34,35,36. In line with these findings, our data showed that FGF23 was inversely correlated with iron profiles, including iron and TSAT, and positively correlated with hepcidin, which induces functional iron deficiency through iron sequestration and inhibition of iron absorption in the gastrointestinal tract37. Furthermore, subgroup analyses showed that a significant association between high FGF23 levels and the development of anemia was evident in patients with iron deficiency and high inflammatory status. It can be presumed that iron deficiency induces anemia either directly or indirectly through a negative impact of FGF23 on erythropoiesis.

Subgroup analyses showed that the use of RAS blockers can affect the relationship between FGF23 and the development of anemia. This association was evident in patients treated with RAS blockers (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.07–1.29; P = 0.001), but not in patients without RAS blockers (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.75–1.45; P = 0.81). Several experimental and clinical studies have suggested possible association between renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and erythropoiesis38,39,40,41. Angiotensin II were demonstrated to be a physiologically important regulator of erythropoiesis, both as a growth factor of erythroid progenitors, and as an erythropoietin secretagogue to maintain increased erythropoietin41. In addition, serum aldosterone levels were demonstrated to play a role in the relationship between FGF23 and hemoglobin levels21. Moreover, RAS activation is reported to induce FGF23 resistance42. These findings together suggest that negative effect of FGF23 on erythropoiesis can be more evident in low renin-angiotensin-aldosterone status. Future studies are required to clarify the impact of RAS on FGF23-associated anemia.

Several shortcomings of this study should be discussed. First, because this is an observational study, it is possible that potential confounding factors were not entirely controlled. However, this study included a large number of patients and yielded consistent results in various multivariable Cox models after rigorous adjustment. Second, patients in our study had relatively higher eGFR than those in a previous study21; thus, the association between FGF23 and anemia needs to be verified in patients with advanced stages of CKD. Although there was no significant interaction between FGF23-related anemia and kidney function, subgroup analyses showed that association between FGF23 levels and incident anemia was particularly evident in patients with eGFR >30 ml·min−1·1.73 m−2. Furthermore, high FGF23 levels were also significantly associated with the future development of anemia in patients with low disease severity (e.g., with well-controlled BP, no diabetes, no obesity, and low comorbid conditions). Presumably, there are many other factors that can affect erythropoiesis in uremic conditions. These unseen factors seem to have overwhelmed the effect of FGF23 on anemia in patients with a high disease burden. Third, although iron deficiency modulates FGF2333,34,35,36, our study did not show that ferritin levels were correlated with FGF23 levels. However, it should be noted that ferritin is an acute-phase reactant and can be elevated in response to uremic inflammatory condition despite the presence of functional iron deficiency. This can explain a poor correlation between ferritin and FGF23 in CKD. Finally, we performed a single measurement of FGF23 concentrations at baseline and had no data for follow-up measurements. It would be interesting to see whether a change of FGF23 level is concordant to that of hemoglobin level. Further longitudinal studies are required to examine this relationship.

In conclusion, this study showed that serum FGF23 levels were inversely correlated with hemoglobin levels in patients with CKD and that patients with high FGF23 levels were more likely to have anemia. Furthermore, in patients without anemia at baseline, elevated FGF23 levels were associated with an increased risk of new development of anemia. Our findings suggest that FGF23 can be a useful predictor of anemia in patients with CKD. Further studies are required to clarify the mechanism for FGF23-associated anemia in these patients.

References

Astor, B. C., Muntner, P., Levin, A., Eustace, J. A. & Coresh, J. Association of kidney function with anemia: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994). Arch Intern Med 162, 1401–1408 (2002).

Stauffer, M. E. & Fan, T. Prevalence of anemia in chronic kidney disease in the United States. PLoS One 9, e84943 (2014).

Levin, A. Anemia and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease populations: a review of the current state of knowledge. Kidney Int Suppl; https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.61.s80.7.x. 35–38 (2002).

Kovesdy, C. P., Trivedi, B. K., Kalantar-Zadeh, K. & Anderson, J. E. Association of anemia with outcomes in men with moderate and severe chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 69, 560–564 (2006).

Jurkovitz, C. T., Abramson, J. L., Vaccarino, L. V., Weintraub, W. S. & McClellan, W. M. Association of high serum creatinine and anemia increases the risk of coronary events: results from the prospective community-based atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol 14, 2919–2925 (2003).

Eschbach, J. W. The anemia of chronic renal failure: pathophysiology and the effects of recombinant erythropoietin. Kidney Int 35, 134–148 (1989).

Weiss, G. & Goodnough, L. T. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med 352, 1011–1023 (2005).

Nangaku, M. & Eckardt, K. U. Pathogenesis of renal anemia. Semin Nephrol 26, 261–268 (2006).

Patel, N. M. et al. Vitamin D deficiency and anemia in early chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 77, 715–720 (2010).

Martin, A., David, V. & Quarles, L. D. Regulation and function of the FGF23/klotho endocrine pathways. Physiol Rev 92, 131–155 (2012).

Gutierrez, O. et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 mitigates hyperphosphatemia but accentuates calcitriol deficiency in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16, 2205–2215 (2005).

Kovesdy, C. P. & Quarles, L. D. Fibroblast growth factor-23: what we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to know. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28, 2228–2236 (2013).

Fliser, D. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) predicts progression of chronic kidney disease: the Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 18, 2600–2608 (2007).

Isakova, T. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Jama 305, 2432–2439 (2011).

Khan, A. M., Chirinos, J. A., Litt, H., Yang, W. & Rosas, S. E. FGF-23 and the progression of coronary arterial calcification in patients new to dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7, 2017–2022 (2012).

Gutierrez, O. M. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 119, 2545–2552 (2009).

Kendrick, J. et al. FGF-23 associates with death, cardiovascular events, and initiation of chronic dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 22, 1913–1922 (2011).

Scialla, J. J. et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and cardiovascular events in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 25, 349–360 (2014).

Gutierrez, O. M. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 359, 584–592 (2008).

Coe, L. M. et al. FGF-23 is a negative regulator of prenatal and postnatal erythropoiesis. J Biol Chem 289, 9795–9810 (2014).

Tsai, M. H., Leu, J. G., Fang, Y. W. & Liou, H. H. High Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Levels Associated With Low Hemoglobin Levels in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 3 and 4. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e3049 (2016).

Eser, B. et al. Fibroblast growth factor is associated to left ventricular mass index, anemia and low values of transferrin saturation. Nefrologia 35, 465–472 (2015).

Mehta, R. et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Anemia in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol; https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.03950417. (2017).

Oh, K. H. et al. KNOW-CKD (KoreaN cohort study for Outcome in patients With Chronic Kidney Disease): design and methods. BMC Nephrol 15, 80 (2014).

Levey, A. S. et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 145, 247–254 (2006).

Akalin, N. et al. Prognostic importance of fibroblast growth factor-23 in dialysis patients. Int J Nephrol 2014, 602034 (2014).

Honda, H. et al. High fibroblast growth factor 23 levels are associated with decreased ferritin levels and increased intravenous iron doses in hemodialysis patients. PLoS One 12, e0176984 (2017).

Kendrick, J., Targher, G., Smits, G. & Chonchol, M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency and inflammation and their association with hemoglobin levels in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 30, 64–72 (2009).

Aucella, F. et al. Calcitriol increases burst forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E) in vitro proliferation in chronic uremia. Synergic effect with DNA recombinant erythropoietin (rHu-Epo). Minerva Urol Nefrol 53, 1–5 (2001).

Aucella, F. et al. Calcitriol increases burst-forming unit-erythroid proliferation in chronic renal failure. A synergistic effect with r-HuEpo. Nephron Clin Pract 95, c121–127 (2003).

Alon, D. B. et al. Novel role of 1,25(OH)(2)D(3) in induction of erythroid progenitor cell proliferation. Exp Hematol 30, 403–409 (2002).

Brancaccio, D., Cozzolino, M. & Gallieni, M. Hyperparathyroidism and anemia in uremic subjects: a combined therapeutic approach. J Am Soc Nephrol 15(Suppl 1), S21–24 (2004).

David, V. et al. Inflammation and functional iron deficiency regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 production. Kidney Int 89, 135–146 (2016).

Farrow, E. G. et al. Iron deficiency drives an autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) phenotype in fibroblast growth factor-23 (Fgf23) knock-in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, E1146–1155 (2011).

Imel, E. A. et al. Iron modifies plasma FGF23 differently in autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets and healthy humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96, 3541–3549 (2011).

Wolf, M., Koch, T. A. & Bregman, D. B. Effects of iron deficiency anemia and its treatment on fibroblast growth factor 23 and phosphate homeostasis in women. J Bone Miner Res 28, 1793–1803 (2013).

Babitt, J. L. & Lin, H. Y. Molecular mechanisms of hepcidin regulation: implications for the anemia of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 55, 726–741 (2010).

Kato, H. et al. Enhanced erythropoiesis mediated by activation of the renin-angiotensin system via angiotensin II type 1a receptor. FASEB J 19, 2023–2025 (2005).

Cole, J. et al. Lack of angiotensin II-facilitated erythropoiesis causes anemia in angiotensin-converting enzyme-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 106, 1391–1398 (2000).

Vlahakos, D. V. et al. Association between activation of the renin-angiotensin system and secondary erythrocytosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 106, 158–164 (1999).

Vlahakos, D. V., Marathias, K. P. & Madias, N. E. The role of the renin-angiotensin system in the regulation of erythropoiesis. Am J Kidney Dis 56, 558–565 (2010).

de Borst, M. H., Vervloet, M. G., ter Wee, P. M. & Navis, G. Cross talk between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and vitamin D-FGF-23-klotho in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22, 1603–1609 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Program funded by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011E3300300, 2012E3301100, 2013E3301600, 2013E3301601, 2013E3301602, and 2016E3300200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. Nam wrote the manuscript, K.H. Nam, H. Kim, S.Y. An, M. Lee, M.U. Cha and J. Lee analyzed the date, J.T. Park, T.H. Yoo, K.B. Lee, Y.H. Kim, S.A. Sung, S.W. Kang, K.H. Choi, C. Ahn and S.H. Han reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nam, K.H., Kim, H., An, S.Y. et al. Circulating Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 Levels are Associated with an Increased Risk of Anemia Development in Patients with Nondialysis Chronic Kidney Disease. Sci Rep 8, 7294 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25439-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25439-z

This article is cited by

-

Association between serum phosphate levels and anemia in non-dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease: a retrospective cross-sectional study from the Fuji City CKD Network

BMC Nephrology (2023)

-

The effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation on hepcidin-25 and erythropoiesis in patients with chronic kidney disease

BMC Nephrology (2023)

-

Fibroblast growth-factor 23 and vitamin D are associated with iron deficiency and anemia in children with chronic kidney disease

Pediatric Nephrology (2023)

-

Interconnections of fibroblast growth factor 23 and klotho with erythropoietin and hypoxia-inducible factor

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2022)

-

Factors associated with 1-year changes in serum fibroblast growth factor 23 levels in pediatric patients with chronic kidney disease

Clinical and Experimental Nephrology (2022)