Abstract

A facile and eco-friendly strategy is described for the synthesis of ZnS-ZnO/graphene heterostructured nano-photocatalysts for the first time. This solvent-free and technologically scalable method involves solid-state mixing of graphite oxide (GO), Zn salt and surfeit yet non-toxic elemental sulfur using ball-milling followed by thermal annealing. The as-formed hybrids are composed of uniformly distributed in-situ formed ZnS-ZnO nanoparticles simultaneously within the thermally reduced GO (graphene) matrix. A series of hybrid compositions with varying content of ZnS/ZnO and graphene were prepared and thoroughly characterized. Further, the effect of heterostructure composition on the photocatalytic properties was investigated under visible-light illumination. The synergistic ZnS-ZnO/graphene hybridization promoted the band-gap narrowing compared to the pristine ZnS nanoparticles. The ZnS:ZnO composition was controlled by graphite oxide under thermal treatment and observed to be a crucial factor in enhancement of photocatalytic activity. As a proof of concept, the phase optimized and surface enhanced ZnS-ZnO/graphene nano-photocatalysts was tested towards visible light driven photocatalytic degradation of environmentally harmful organic dyes and toxic phenol molecules from aqueous media. The presented cost-effective strategy provides high potential in large-scale production of heterostructured nano-photocatalysts for environmental remediation and photocatalytic greener production of hydrogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the ever-growing environmental concerns, the quest for highly active and low cost yet visible light responsive photocatalyst for effective environmental remediation is still ongoing and emerged as an important thrust area of research1,2,3. So far, semiconductor based nanostructured materials have attracted great deal of interests as a potential photocatalyst4,5,6. However, due to poor absorption of light and fast recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes, these individual semiconductors further needs fine-tuning in order achieve unique band gaps that can effectively utilize light energy for oxidative degradation of toxic organic compounds and pollutants. Hence, nanoscale hybridization of individual photocatalysts with hierarchical structure and dimensions offers innovative and efficient strategy to fabricate photocatalyst with enhanced photo-response and deprived electron-hole recombination5,7,8. Therefore, wide arrays of coupled semiconductor based heterostructured nanohybrids were synthesized and used for various photocatalytic transformations9,10,11. However, most of them are fancy and complex ternary chalcogenide compounds based photocatalysts which display a strong visible-light absorption and narrow band gaps, but their production complexity and high-cost is still a major roadblock from an industrial application perspectives12. Hence, in this context, the nanostructured hybrids composed of conventional photocatalysts such as ZnS and ZnO with wide range band gap (Eg = 3.54 and 3.37 eV at 300 K, respectively) are still considered as the most attractive photocatalyst option mainly because of its exceptional optical properties, environmental sustainability and cost-effectiveness13,14,15. It has been demonstrated that the heterostructure combination of both ZnO and ZnS are better in realizing the photocatalytic decomposition of the organic pollutants over the individual components16. Also, the band gap of these nanoparticles can be narrowed to visible region by creating ZnS-ZnO heterostructures17. The typical synthesis methods that are commonly used in the preparation of such hybrid photocatalysts comprise wet-chemical synthesis18,19, co-precipitation method20, thermal and hydrothermal methods21,22,23, also sulfurization of ZnO with noxious H2S gas at high temperatures was also practiced24,25. Furthermore, most of these processes are highly intricate and uses toxic agents, which can restrict their large-scale productions. Hence, the development of inexpensive, scalable and environment friendly method to prepare such heterostructured nanohybrids is the key to the commercialization of photocatalysts for waste water treatment and other environmental remediation applications.

Furthermore, surface immobilized photocatalysts are often exhibit significantly higher remediation due to internal efficiency related to separation, and establish affinity towards external contaminant molecules etc26,27. Recently, Ma et al.20 has successfully demonstrated the formation of ZnO-ZnS/carbon hybrids as an efficient photocatalyst in dye removal. In this context, in addition to its size controlling effect and surface area enhancing activity, if support material can also contribute to the photocatalytic activities of such heterosructures then that could be an interesting photocatalyst composition. For example, the hybridization of individual ZnS and ZnO nanoparticles with graphene is known to prevent the nanoparticles from aggregating due to its layered structures and high surface area and uniform nanoparticle distribution can be achieved28,29. These nanohybrids showed improved photocatalytic characteristics due to the electron detention and its transferability within graphene that effectively prevent the recombination the photo-excited charge carriers i.e electrons and holes16. Also, graphene demonstrated as macromolecular sensitizer that can transform ZnS from wide band gap semiconductor to the visible light photocatalyst30. Thus, the incorporation of graphene together with semiconductor nanocomposites can significantly enhance the photocatalytic performance in degradation of dyes and other organic pollutants31. Hence, we believe that hybridizing ZnS-ZnO heterostructures with graphene could further enhance the photoactivity of the resulting photocatalyst under visible light. The addition of GO provides dual role, first it provides valuable support to nucleate nanoparticle precursors and later during thermal annealing process, the liberated oxygenated species can effectively oxidize some of the ZnS into ZnO.

In the present research work, we report a simple, scalable and environment friendly approach for the first time to fabricate nano-photocatalyst hybrids composed of ZnS-ZnO and graphene. The formation mechanism of ZnS-ZnO and simultaneous reduction of GO was explained according to a series of experiments and structural characterizations. The photocatalytic efficiency, adsorption performance and recyclability of the nanohybrids is estimated by monitoring the most prominent industrial water contaminants i.e organic dyes such as cationic (methylene blue, MB), anionic (methyl orange, MO) and toxic nitro-phenols (2-NP and 4-NP) as model pollutants. It is demonstrated that the hybridization of ZnS-ZnO heterostructure and graphene can potentially lower the rate recombination of photo-generated charge carriers and exhibit a significant photocatalytic activity and efficiency.

Result and Discussion

The formation mechanism of the as-prepared ZnS-ZnO/graphene composites prepared via solid-state synthesis is shown in Fig. 1. In this study, zinc hydroxyacetate was used as the source of zinc, surfeit and non-toxic elemental sulfur as a sulfur source and graphite oxide as graphene precursor. During the ball milling process, the zinc hydroxyacetate and sulfur was homogenized through intercalation into layered GO. Then, under thermal treatment Zn2+ simultaneously reacts with in-situ formed reactive sulfur and oxygenated species liberated through thermal decomposition of both Zinc salt and GO to form spherical ZnS and ZnO nanocrystals under different stoichiometric conditions. The surface of the thermally reduced GO (graphene) sheets was expected provide support for ZnS/ZnO nucleation sites, resulting in a uniform dispersion of nanosized heterostructured particles onto graphene. Evidently, the color change was observed from brownish to grey and become darker with increasing the graphene content.

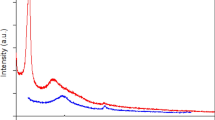

The crystalline structures and phase orientations of ZnS-ZnO/graphene nanostructured hybrids are examined by PXRD analysis (Fig. 2). For ZnS, the peaks at 28.59°, 47.62°, and 56.47° were recorded which can be indexed to the (111), (220), and (311) planes of the cubic ZnS (JCPDS 36-1450). Similarly for ZnO, the sharp peaks at 31.83°, 34.48°, 36.32°, 47.62°, 56.76°, and 62.93° indicated the existence of a wurtzite phase of as formed ZnO structure (JCPDS No. 36-1451). After thermal treatment of ball milled homogeneous mixture of zinc salt, sulfur and GO, the characteristic peaks similar to ZnS and ZnO nanoparticles are found in the XRD patterns of resulting nanostructured hybrids (Fig. 2c–e). In addition, an appearance of a new broad peak around 25.57° was solely indicated the characteristic (002) planes of the graphene (Fig. S1), which gradually intensify with graphene loading. The disappearance of the characteristic peaks assigned to graphite oxide around 2θ = 9.7° in Z2G composites indicated the successful thermal reduction of the layered GO into graphene. It has been also observed that the loading of GO played significant role in the formation of both ZnS an ZnO phases in the resulting Z2G hybrid. For Z2G-3 hybrids, intensity of the peak corresponding to the ZnO phase was gradually increases in compared to Z2G-1, which is attributed to the increasing amount of oxidative GO in the starting composition. These results confirm that the GO offers more oxygenated species in order to oxidize the ZnS in to ZnO and eventually control the ZnS:ZnO ratio in the final nanohybrid composition which is proportional with GO content (Fig. S2). Further, the absence of any other dominant peaks in resulting XRD pattern confirms that the Z2G nanohybrids were exclusively made up of ZnS, ZnO and graphene phases. Furthermore, the average crystallite size of ZnS and ZnO in resulting Z2G nanohybrids was estimated using Debye-Scherrer’s equation (1)32:

where D is average crystallite size (nm); K dimensionless shape factor, with value of 0.89; λ represent X-ray wavelength; β stands for the line broadening at half the maximum intensity and θ is the Bragg angle. The calculated crystallite size is presented in Table 1.

It can be seen that the particle size of ZnS is significantly decreased with increasing the content of graphene and similar trend was observed for ZnO nanoparticles. These results underline that role of graphene nanosheets which can act as an excellent support in controlling the size of these in-situ formed ZnS-ZnO heterostructured nanohybrid particles.

The morphological and structural evolutions during the in-situ synthesis of these as-prepared nanohybrids were investigated by TEM and SEM measurements. Figures 3a,b and S3 represents the typical TEM image of a Z2G-1 hybrid, which indicates the in-situ formed ZnS-ZnO nanoparticles (ca. 5–20 nm) are uniformly distributed and tightly aggregated on the graphene support was observed. The HRTEM micrograph (Fig. 3c) indicated the interface region of a characteristic heterojunction, and the typical lattice fringes of the nanoparticles. The characteristic lattice fringes of the ZnS nanoparticles having lattice spacing of 0.32 nm for (111) planes are well intermixed with lattice fringes of the ZnO having the lattice spacing of 0.24 nm for (101) planes were observed. This observation clearly reveals formation of heterostructured nanohybrids composed of cubic blende ZnS intermixed wurtzite ZnO and graphene33. Besides, the SAED pattern (Fig. 3d) displayed a set of well-defined diffraction rings which indicates the existence of highly crystallized ZnS-ZnO nanoparticles in the resulting nanohybrids, which is in agreement with the XRD result shown in Fig. 1.

The SEM in conjunction with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) gives more insight on the morphological features and the elemental composition of the as prepared Z2G hybrids and same were showed in Fig. 4 for Z2G-1 sample. It can be clearly seen that the ZnS-ZnO heterostructure with spherical assemblies were uniformly spread on the surface of the wrinkled micro sheets 2D graphene (Fig. 4a). The EDS spectrum of Z2G-1 hybrid (Fig. 4b) shows the corresponding elemental composition indicating Zn, S, O and C elements which further confirmed heterostructured hybrid formation, composed of ZnS-ZnO and graphene. Further, the elemental mappings showed in Fig. 4c confirm uniform distribution of the ZnS-ZnO species supported by graphene. Similarly, the other hybrids (Z2G-2 and 3) also showed similar morphological features but the increase in graphene content cause more crumpling and agglomerated sheet like morphology in compared to pristine ZnS nanoparticles spherical morphology (Fig. S4).

The decreased S/O ration with increase in GO content for Z2G-2 and 3 further confirmed the higher conversion of ZnS into ZnO under oxidative thermal treatment. In summary, ZnS-ZnO heterostructures have been in-situ formed and deposited on the graphene nanolayers which significantly changed the morphology and the ratio of ZnS-ZnO heterostructure in the final nanocomposites. Overall, both TEM and SEM investigations confirms the formation of good interfacial contact between ZnS-ZnO nanostructures and graphene sheet due to synergetic effect between individual components. Such interfacial interactions are critical from photocatalysis perspectives considering the improved charge transfer process between graphene and semiconductor nanoparticles34.

The chemical composition and the binding energy state of the resulting Z2G heterostructured nanohybrids were determined by XPS measurements. As showed in Fig. 5a, the XPS survey spectra of the Z2G-2 sample clearly indicates the characteristic peaks of Zn2p, S2p, C1s, and O1s and absence of any other element peak confirms pure state of the as formed ZnS-ZnO nano-assemblies within graphene layered network. The high resolution C1s spectrum (Fig. 5b) shows three characteristic peaks with binding energies of 284.4, 285.5, and 289.9 eV that are attributed to the carbon atoms such as delocalized sp2 -hybridized C–C/C=C, C–O, and O–C=O groups, respectively35. The decrease in these peak intensities compared to GO (Fig. S5) further indicates that the thermal reduction of the GO during the formation of Z2G nanohybrids under thermo-annealing process. The reduction of GO to graphene is known to develop the high electron mobility, necessary for the enhancement of photocatalytic process36. The Zn 2p spectrum displays characteristic peak at 1022 eV, attributed to the Zn 2p3/2 spin orbit peaks of the ZnS and ZnO phase28,37. The presence of ZnS can be further confirmed by the S2p spectrum (Fig. 5d) with the characteristic peaks at 161.8 and 163.1 eV, which indicate the S2p3/2 and S2p1/2 peaks in the ZnS phase37. Similarly, Fig. 5e showed the high resolution O1s peak for Z2G-1, which can be fitted into two peaks. The lower energy peak located at 531.0 eV corresponded to the oxygen atoms coordinated with Zn atoms in ZnO lattice. On the other hand, the higher binding energies located at 532.5 eV in Z2G nanohybrid could be due to the presence of hydroxyl groups (O hydroxyl) and other oxygen functional groups coming from graphene, respectively28. Therefore, the XPS results indicated the ZnS particles formed on the graphene surface with some oxygen-containing groups corresponds to the existence of ZnO particles.

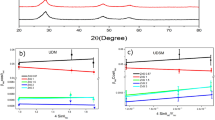

The UV-visible diffuse reflectance converted absorbance spectrum was recorded to evaluate the optical properties of the resultant Z2G nanohybrids and pristine ZnS/ZnO nanoparticles as shown in Fig. 6a. It was noted that the addition of graphene extends nanohybrid absorbance into the visible region, which was further supported by color change of the sample (in-set Fig. 1). The band gap energy measured by employing Kubelka-Munk function showed band gap around 3.11 eV and 3.01 eV for ZnS and ZnO nanoparticles, which is narrower than their bulk counterparts38. In the graphene containing samples, Z2G-1 and Z2G-2 shows band gap of 2.96 eV and 2.87 eV, respectively. Due to high background absorption we could not able to measure the band gap for Z2G-3 sample. These findings indicated that the band gap energy of the resulting ZnS-ZnO heterostructure was lowered when hybridized with 2D graphene at nanoscale which in agreement with previous reports for graphene nanohybrids such as ZnS-graphene30 and TiO2-graphene39,40. Overall, the improved optical properties for the resulting ZnS-ZnO/graphene heterostructured hybrids would be beneficial for visible-light harvesting and photocatalysis applications.

The prospects of the photo-induced electron–hole pair recombination was further investigated using photoluminescence (PL) spectra at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm (Fig. 6b). The PL spectra of ZnS nanoparticles and Z2G hybrids show a sharp blue emission peak around 390 nm. The intensity of UV emission at 390 nm is related to the electron and hole pair recombination in the conduction and valence band, respectively41. In addition, the blue-green emissions in the range between 450 to 550 nm (visible region) were observed, which can be attributed to the sulfur vacancies and interstitial lattice defects. Further, the green emission is owing to the self-activated defect centers related to Zn-vacancies present in ZnS nanoparticles42. It was observed that the PL peak intensities for Z2G hybrids are significantly lowered with increase in graphene content which also implies the subsequent increment in the ZnO content. Such quenching implies that an active interfacial charge-transfer process occurred between the photo-excited ZnS-ZnO nano-assemblies and the graphene sheets. This also paves an additional pathway for disappearance of the charge carriers during the photo-excitation process. Further, the high electron affinity of graphene can attract more photo-excited electrons from the ZnS-ZnO heterostructure; such electron acceptor-donor combination could lead to an energetic electron transfer from ZnS to Z2G-3 and can reduce possible electron–hole pair recombination effectively.

Figure 6c shows the nitrogen gas adsorption-desorption isotherms of the resulting ZnS and ZnS-ZnO/graphene nanohybrid samples. According to the IUPAC classification, all of these isotherm patterns can be classified as near type IV isotherm which is characteristic of the inhomogeneous mesoporous materials having H1 hysteresis loop. The BJH pore size distribution curves of the nanohybrids are shown in Fig. 6d. The measured BET surface areas for ZnS and ZnS-ZnO/graphene nanohybrids are presented in Table 2. After hybridization, the surface areas tend to increase with increase in graphene content, this further evidence the in-situ formation of nanostructured hybrids. Mesoporosity in the resulting nanohybrids were further confirmed from the pore size distribution peaks that are centered around a 2 nm and a broad peak around 7.6 nm43. The total volume of pores for nanohybrids was between 0.094 to 0.254 cm3g−1, respectively. Both the BET surface area and the average pore size of the ZnS-ZnO/graphene hybrids are larger than those of pure ZnS, which indicates that the resulting nanohybrids can provide a larger interface to enhance the contact between the dye and the active catalyst and facilitate photocatalytic reaction.

The loading of ZnS and ZnO in the final ZnS-ZnO/graphene heterostructured nanohybrids under different graphite oxide concentrations were summarized in Table 3. As the concentrations of stoichiometric amount of GO used to obtain graphene was increased from 11.1 to 66.9 wt%, the weight percent of ZnS decreased from 90.88 to 56.17 wt-%. Similarly, relative to ZnS, the ZnO concentration in hybrid was increased from 4.11 to 15.54 wt-%. These results indicated that the higher GO amount used as graphene precursor is oxidizing the ZnS in to ZnO during in-situ process to obtain ZnS-ZnO heterostructure and thermal reduction of GO simultaneously.

Raman spectroscopy was also employed to investigate the crystal structure of ZnS-ZnO-graphene nanohybrids (Fig. S6). For Z2G-1, Raman peaks appear at 212 cm−1 and 329 cm−1 corresponding to the characteristic E1 (TO) and A1 (LO) modes of the ZnS44. A blue shift in both E1 and A1 energy modes for Z2G-1 in compared to the bulk ZnS (E1: 274 cm−1 and A1: 352 cm−1) was observed which can be attributed to the confinement effect of optical phonons in the ZnS nanoparticles45. Similarly, Raman bands at about at 425 cm−1 and 560 cm−1 assigned to A1 (TO) and E2 (high) vibration modes of wurtzite ZnO were observed46. The increase in the intensity of ZnO peaks in Z3G hybrids can be ascribed due to the oxidation ZnS under high power laser. Additionally, graphene exhibit two main peaks attributed to the D-band at 1354 cm−1 evolved from distortion of sp2 structure by creation of sp3 carbon centers, whereas the G-band occurred at about 1589 cm−1, is due to E2g mode and arise from the stretching of the C-C bond in the graphitic materials.

Owing to its tunable band structure, the resulting Z2G nanohybrids are expected to display enhanced photo-catalytic properties. Hence, the visible-light driven degradation of harmful dyes such as methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO) and toxic nitro-phenols (2-NP and 4-NP) were carried out as performance assessment test for synthesized nano-photocatalysts and showed in Fig. 7. First, the MB and MO dye adsorption and photocatalytic performance of Z2G nanohybrids and ZnS nanoparticles was tested (Fig. 7a–d). Since the Z2G nanohybrids are highly porous and having more surface area over pristine ZnS nanoparticles, it was expected that hybrids can exhibit characteristic dye adsorption phenomenon. Hence, to monitor the adsorption characteristic of the resulting nanohybrids, the adsorption measurements the dark were also performed. It was observed that the Z2G hybrids shows higher equilibrium adsorption capacity compared to ZnS which exhibit smallest capacity. Amongst Z2G hybrids, the adsorption capacity for both the dyes increases with increasing graphene content and which is due to increased micropore volume and the higher surface area (Table 2). Further, the visible light driven photocatalytic degradation of dye was studied at different time intervals. The MB dye degradation efficiency of the photocatalysts was measured to be around 99%, 87%, 79% and 59% using the Z2G-2, Z2G-1, Z2G-3 and ZnS photocatalysts, respectively under 90 minutes of irradiation (Fig. 7a). Similarly, for MO the dye degradation efficiency of the photocatalysts was measured to be 97.5%, 84.5%, 68.5% and 47% for Z2G-2, Z2G-1, Z2G-3 and ZnS photocatalysts, respectively for 160 minutes of light irradiation (Fig. 7c). The superior photocatalytic activity of the Z2G-2 nanohybrids in both the cases was ascribed due to the several comprehensive factors. First, the synergy between ZnS-ZnO heterostructure and smaller crystallite size of both ZnS and ZnO due to introduction of graphene which implies that Z2G possesses resilient oxidation-reduction capacity owing to the quantum-size effect47. Second, the improvised surface properties of the nanohybrid could offer abundant active sites required for efficient light harvesting, resulting into improved photocatalytic activity36. Third is the integration of the graphene that could lead to the significant reduction of electron–hole pair recombination through photosensitization. Furthermore, among the Z2G nanohybrids, a higher photocatalytic performance was noted for Z2G-2 sample which could be attributed to the optimized composition of photocatalytically active ZnS-ZnO heterostructure and graphene in Z2G sample. Also, a relatively higher surface area, which was expected to offer more sites for the photocatalytic activity. The lower photocatalytic activity was noted for Z2G-3 because the potential catalytically active sites can be clogged due to the higher graphene content, thereby shielding of the incident light that can reduces the light absorption by ZnS-ZnO photocatalyst36. Also, using Z2G-2 photocatalyst the spectral peak intensity of MB dye at 664 nm (Fig. 7b) and MO dye at 460 nm (Fig. 7d) was gradually gone down with increasing irradiation time indicating the photodegradation of the dyes. Further, the inset images indicated that upon given visible light irradiation time, a complete dye discoloration was also achieved.

The photocatalytic activities of the nanohybrids were further analyzed by studying kinetics of photocatalytic degradation using Langmuir–Hinshelwood model48:

where r is the degradation rate of the reactant (mg L−1 min−1), C is the concentration of the reactant (mg L−1), k1 is the reaction rate constant (mg L−1 min−1), k2 is the adsorption constant of the reactant (L mg−1). When C is very small, the equation can be simplified to:

where C0 is the initial concentration of the reactant and Kt is the first-order rate constant obtained from the slope of the graph of ln(C0/C) vs. time (t). Figures S7 and S8 shows the plots of ln (C0/C) vs. time for Z2G nanohybrids and ZnS NPs, which resulted into straight lines confirming the degradation of both MB and MO, follows the first-order kinetic reaction behavior. The MB dye photodegradation rate constants (K) for the Z2G-1, Z2G-2, Z2–3 and ZnS NPs samples were measured to be 0.012, 0.024, 0.009 and 0.005 min−1, respectively. The Z2G-2 nanohybrid showed about 5 times highest K value compared to the ZnS NPs and 1.5 times of Z2G-3 hybrids, respectively. Hence, the higher K value indicates a higher photocatalytic dye degradation rate for Z2G-2 nanohybrid. For MO, the estimated K values are 0.011 (Z2G-1), 0.019 (Z2G-2), 0.009 (Z2G-3) and 0.006 (ZnS) min−1, further signifies the higher photocatalytic activity for Z2G-2 nanohybrids. As discussed earlier, the higher K values can be attributed to the optimized composition of in-situ formed and graphene wrapped nanosized ZnS-ZnO assemblies, reduced recombination of charge carriers, and band gap narrowing. Similar to the enhanced rate of photodegradation and superior kinetics, the recyclability of a given photocatalyst in the course of photocatalytic reaction is equally important and considered as a critical factor from large scale practical application perspectives. The recyclability tests were therefore performed by repetitive photocatalytic reaction using Z2G-2 photocatalyst under visible light irradiation. It has been observed that after 5 cycles of repeated use, the decrease in photocatalytic efficiency was merely about 6.3% for MB and 8.5% for MO was observed (Fig. S9). These findings revealed the significant stability of the resulting heterostructured Z2G nanohybrids photocatalyst.

In addition to the dyes, the photocatalytic degradation of highly toxic phenolic pollutants i.e 2-nitrophenol and 4-nitrophenol was also investigated using the fabricated heterostructured nano- photocatalysts as showed in Fig. 8. It can be seen that the decrease in characteristic spectral peak intensity of 2-nitrophenolate at 403 nm which gradually gone down (Fig. 8a) and discoloration of the phenolate (inset of Fig. 8a) with increasing irradiation time indicating the photodegradation of the nitrophenol. As shown in Fig. 8b, the hybrid Z2G-2 exhibits the best photocatalytic activity toward photocatalytic degradation of 2-nitrophenol, which is almost double the activity of nano ZnS and also higher compared to other Z2G nanohybrids after 200 min of visible light irradiation. Similarly, for 4-nitrophenol, the decrease of the peak intensity at 317 nm is clear evidence of its continuous effective degradation under visible light using this nanohybrid photocatalyst (Fig. 8c). The high degradation efficiency of 4-NP was noted for Z2G-2 nanohybrid. No additional reducing agents were used, which further confirm the photocatalytic degradation was attributed to a direct photo-hole oxidation and superoxide anions which are known to degrade and mineralize the phenolates under visible light irradiation49. Overall, the results confirm that at optimized composition of ZnS-ZnO heterostructure and graphene, owing to the synergistic effects fostered from individual components, the synthesized ZnS-ZnO/graphene nano-photocatalysts displayed significant effectiveness in removal of toxic pollutants from aqueous media.

For better understanding of the photocatalytic mechanism, it is important to investigate the active species formed during photocatalytic process. In general, photocatalytic degradation of dyes and phenols primarily comprises several active radical species which includes hole (h+), electrons (e−) superoxide anion radical (●O2−), and hydroxyl radicals (●OH)50. Hence, to distinguish the role of the reactive species, scavenging analysis were performed using series of scavengers during the photodegradation process of MB. Figure 9 shows the photocatalytic degradation of MB over Z2G-2 nanohybrid in the presence of different scavengers under visible-light irradiation. A remarkable decrease in photocatalytic activity of the Z2G-2 nanohybrids was observed in presence of BQ and EDTA-2Na scavengers, highlighting that the both photo-generated superoxide anion radicals and holes are the main oxidative species and play key roles in the photocatalytic process of MB under visible irradiation. In contrast, the photodegradation efficiency of MB is slightly affected in presence of AgNO3, indicating e− are not the dominant active species in this process. Similarly, using t-BuOH, a moderate decrease in efficiency was recorded implying that the ●OH species plays adequate role in the degradation process.

Briefly, these scavenging experiment results point out that the photogenerated holes and ●OH species together with superoxide anion radicals makes the main oxidative force for photocatalytic degradation of the pollutants.

Hence, considering the importance of the formation of reactive radical species during the photoexcitation process, the mechanism of photocatalytic dye degradation can be presented as shown in Fig. 10. Under photo-irradiation, the ZnS-ZnO heterostructures excite the electrons from its valence band (VB) state to the conduction band (CB) state and eventually form the electron–hole pairs. During this transformation, the VB is left with the positively charged holes which lead to the formation of hydroxyl radicals. Similarly, on other hand the electrons generated at conduction band (CB) are reactive enough to reduce the molecular oxygen. Hence, the resulting reactive radical species possesses powerful oxidizing properties which are highly effective in carrying out degradation of the dye molecules51. Also, the presence of graphene play dual yet pivotal role in enhancing the visible light photocatalytic activity of the ZnS-ZnO heterostructure. Firstly, by lowering the rate of electron–hole pair recombination through effective electron transfer from the CB of ZnS-ZnO to graphene reservoir through percolation mechanism36 and secondly by boosting the visible-light photocatalytic activity of ZnS-ZnO by photosensitization30. Under visible light irradiation, photo-excited electrons are generated from graphene and then transferred to the CB of ZnS-ZnO, which therefore transforms wide band gap ZnS-ZnO to a visible light photocatalyst. Such a photocatalytic reaction mechanism has also been proposed in previous semiconductor-graphene or carbon nanotube visible light photocatalysts30,52. Furthermore, bestowed with exceptional electron conductivity, the layered graphene network could promote the rapid mobility of the reactive charge carriers and consequent separation of the charge may occur. The photocatalytic degradation pathway and formation of intermediates for MB53, MO54, nitro-phenols49 have been extensively studied which indicates the final decomposition of these pollutants resulted into smaller harmless species such as water, CO2, NO3−, ONOO− etc., respectively. Thus, owing to the above mentioned facts the as prepared Z2G nanohybrids display higher photocatalysis performance in decomposition of both anionic and cationic organic dyes and nitrophenols.

Conclusions

A highly efficient, solvent-free and scalable method to prepare heterostructured nanohybrids of ZnS-ZnO/graphene using nontoxic and surfeit elemental sulfur as sulfidizing agent was reported. A series of nanohybrids with controllable ZnS:ZnO heterostructure composition and weight loading of graphene was in-situ fabricated and thoroughly characterized. The results verified that the nanohybrid composition includes nanosized cubic ZnS and wurtzite ZnO nanoparticles that are uniformly distributed within graphene matrix. Further, we firstly reported that, the content graphene precursor (GO) play key role in the controlling the ZnS:ZnO composition in the final nanohybrids. A remarkable photocatalytic activity was achieved for resultant nanohybrids under visible light and effective degradation of dyes (MB and MO) and nitro-phenol was accomplished, which underlined the versatility of the fabricated nano-photocatalysts. The enhanced photoactivity was ascribed to the lowered recombination rate for the photo-generated charge carriers, facile charge transfer and photo-sensitization-cum-strong dye adsorption due to the presence of graphene. Amongst nanohybrids, composition containing 10 wt% graphene and higher ZnO:ZnS ratio, showed superior photocatalytic activity which is due to the lower band gap, higher generation of electron–hole and their rapid transport. Overall, the present study offers greener pathway to fabricate ternary nanocomposites having tailored composition for wide range of applications.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

The following chemicals, graphite powder (Sigma–Aldrich, 10 mesh), sulfuric acid (Sigma–Aldrich, ACS reagent, 95.0–98.0%), hydrochloric acid (Sigma–Aldrich, ACS reagent, 37%), potassium permanganate (Fischer Scientific, ≥99%), hydrogen peroxide (Sigma–Aldrich, 30 wt% in H2O), sodium hydroxide (Sigma–Aldrich, ACS reagent, ≥97.0%), zinc acetate dehydrate (Sigma–Aldrich, ACS reagent, ≥98%) and phosphoric acid (Sigma–Aldrich, ACS reagent, ≥85 wt% in H2O). Scavengers p-benzoquinone (BQ), t-Butanol (TBA), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA-2Na), and AgNO3 (all Sigma–Aldrich) were used as received. Zinc hydroxyacetate was prepared by procedure presented in our previous article28.

Graphite oxide (GO) synthesis

A graphene precursor i.e graphite oxide was synthesized from oxidative exfoliation of the natural graphite by using improved Tour’s method55. Typically, sulfuric acid (200 ml) and phosphoric acid (25 ml) was simultaneously added to the 5 litter Erlenmeyer flask and mixture was cooled in ice-bath. To the cold acid mixture, the natural graphite (5 gm) was added and mixture was continuously stirred to achieve uniform dispersion of the flakes. Afterwards, potassium permanganate (2.7 gm) was added in portions over 30 min. To ensure the complete graphite oxidation, the final mixture was then continuously kept under stirring for 3 days at ambient temperature. The oxidation reaction was apparently evidenced by noticing the colour change from purplish green to dark brownish. Subsequently, the oxidation reaction was terminated by adding hydrogen peroxide (35%) solution, and immediately the colour of the reaction mixture was changed to golden yellow, demonstrating a high degree of graphite oxidation. The as –prepared GO dispersion was repeatedly washed using diluted hydrochloric acid (1 M) to remove the residual salts, metal ions and other impurities. Finally, the GO dispersion was subjected to the dialysis process in de-ionized water to attain stable pH value 6 to 7.

Preparation of ZnS-ZnO/graphene nanohybrids (Z2G)

In typical procedure, 500 mg GO powder, stoichiometric quantity of zinc hydroxyacetate and elemental sulfur were ball milled using IKA ULTRA-TURRAX® Tube Drive control homogenizer at 4000 rpm for 30 min using 5 balls, each weighing 509.3 mg. Further, the resulting mixture was thermally treated in a tubular furnace at 400 °C for 2 hours with a constant heating rate of 5 °C min−1 under continuous argon flow to finally obtain ZnS-ZnO/graphene heterostructured nanohybrids (Scheme 1). Also, based on composition, the colour of the final hybrids was changed from light brown to greyish-black. A stoichiometric amount of GO was used in order to obtain composites with 5, 10, and 30 wt% graphene loading and abbreviated as Z2G-1, Z2G-2 and Z2G-3 respectively. For comparison, similar methodology was employed to prepare pristine ZnS nanoparticles.

Characterization

As prepared samples of Z2G nanohybrid and ZnS nanoparticles were extensively characterized using different techniques. The X-ray powder diffraction (PXRD) analyses were conducted on a Philips X’Pert Pro X-Ray diffractometer equipped with a scintillation counter and Cu-Kα radiation reflection mode. The microscopic morphology and structures of the samples were characterized using a FEI Tecnai (G20) transmission electron microscope (TEM/HRTEM) and Zeiss (1540 XB) scanning electron microscope (SEM) coupled with energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX). The X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were conducted by using a Surface Science Laboratories, Inc. (SSX-100) system equipped with a monochromated Al Kα X-ray source, a hemispherical sector analyzer (HSA) and a resistive anode detector. The specific surface area and porosity of the resulting Z2G nanohybrids were obtained using ASPS 2010 (Micromeritics, USA) Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) nitrogen adsorption-desorption at liquid N2 temperature. The samples were pre-treated at 100 °C in a high vacuum for 24 h before N2 adsorption using a Quantachrome Autosorb gas-sorption system. The Raman spectra of the Z2G nanohybrids were measured using a Raman microscope (LabRam HR, Horiba Scientific) with an excitation wavelength of 633 nm. The optical absorbance spectroscopy in absorbance and diffuse reflectance mode was recorded using Shimadzu UV-vis-NIR spectrophotometer (Model UV-3600) over a wavelength range of 200 to 800 nm. Room temperature photoluminescence spectra were obtained from Shimadzu spectrophotometer (RF-5301PC), and the excitation wavelength was 350 nm. The elemental analysis was performed on EuroVector (EUROEA3000) CHNS element analyser. UV-visible absorption spectrum was recorded on Cary 500 UV-vis spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). The ball milling performed on IKA ULTRA-TURRAX® Tube Drive control homogenizer using five stainless steel balls, each weighing 509.3 mg.

Photocatalytic activity

First, the as-prepared photocatalyst samples (10 mg) were dispersed in 100 mL deionized water using ultra-sonication. Later, 100 mL of aqueous solution of the respective dyes and nitro phenol (1 × 10−5 mol L−1) was added to the catalyst dispersion under continuous stirring. The resultant dispersed solution was then stirred in the dark in order to achieve the adsorption–desorption equilibrium for the photocatalysts, dye and dissolved oxygen. Consequently, the suspension was exposed under a visible light source (400 W metal halide lamp with spectral range 420–700 nm, OSRAM, Germany). The reaction flask was mounted in such way that the incident light was directed to the surface of the solution at a distance of 10 cm. 3 mL aliquots of the suspension were taken at regular irradiation intervals and centrifuged to separate the photocatalyst. The absorption of the clear supernatant was monitored using a UV-Vis spectrometer. The concentration of the remnant contaminants was determined by recording the changes in the absorbance of solutions at maximum of 664 nm, 460 nm and 403 nm for MB, MO and phenolates, respectively during the photocatalytic process.

The efficiency of photodegradation in percentage is calculated from the equation (4) given below:

where C0 = initial dye concentration and Ct = concentration of dye after photodegradation at time ‘t’.

For the radical scavengers experiments, 10 mg of photocatalyst was dispersed into 50 mL of the MB (10 ppm) solution, and then 20 mg of p-benzoquinone (BQ), t-Butanol (TBA), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA-2Na), and AgNO3 were used as superoxide anion radical (●O2−), ●OH scavenger, h+ (holes) scavenger, and e− scavenger, respectively. Before irradiation, the solution was continuously stirred for 30 min in the dark to achieve absorption-desorption equilibrium and subsequently irradiated. An aliquot of 5 mL solution was withdrawn and analyzed with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to measure its absorbance.

References

Colmenares, J. C. & Luque, R. Heterogeneous photocatalytic nanomaterials: prospects and challenges in selective transformations of biomass-derived compounds. Chemical Society Reviews 43, 765–778 (2014).

Bhatkhande, D. S., Pangarkar, V. G. & Beenackers, A. A. C. M. Photocatalytic degradation for environmental applications - a review. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 77, 102–116 (2002).

Jing, L. Q., Zhou, W., Tian, G. H. & Fu, H. G. Surface tuning for oxide-based nanomaterials as efficient photocatalysts. Chemical Society Reviews 42, 9509–9549 (2013).

Chong, M. N., Jin, B., Chow, C. W. K. & Saint, C. Recent developments in photocatalytic water treatment technology: A review. Water Research 44, 2997–3027 (2010).

Li, X., Yu, J. & Jaroniec, M. Hierarchical photocatalysts. Chemical Society Reviews 45, 2603–2636 (2016).

Zhang, N., Liu, S. Q. & Xu, Y. J. Recent progress on metal core@semiconductor shell nanocomposites as a promising type of photocatalyst. Nanoscale 4, 2227–2238 (2012).

Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Liu, B., Sang, Y. & Liu, H. Heterostructures construction on TiO2 nanobelts: A powerful tool for building high-performance photocatalysts. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 202, 620–641 (2017).

Lin, Y.-F. & Hsu, Y.-J. Interfacial charge carrier dynamics of type-II semiconductor nanoheterostructures. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 130, 93–98 (2013).

Yousaf, A. B. et al. Synergistic effect of interfacial phenomenon on enhancing catalytic performance of Pd loaded MnOx-CeO2-C hetero-nanostructure for hydrogenation and electrochemical reactions. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 5, 10704–10712 (2017).

Yousaf, A. B., Imran, M., Zaidi, S. J. & Kasak, P. Highly Efficient Photocatalytic Z-Scheme Hydrogen Production over Oxygen-Deficient WO3–x Nanorods supported Zn0.3Cd0.7S Heterostructure. Scientific Reports 7, 6574 (2017).

Imran, M., Yousaf, A. B., Kasak, P., Zeb, A. & Zaidi, S. J. Highly efficient sustainable photocatalytic Z-scheme hydrogen production from an α-Fe2O3 engineered ZnCdS heterostructure. Journal of Catalysis 353, 81–88 (2017).

Deng, F. et al. One-step hydrothermal fabrication of visible-light-responsive AgInS2/SnIn4S8 heterojunction for highly-efficient photocatalytic treatment of organic pollutants and real pharmaceutical industry wastewater. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 219, 163–172 (2017).

Zhao, H. et al. Facile preparation of a ZnS/ZnO nanocomposite for robust sunlight photocatalytic H2 evolution from water. RSC Advances 5, 6494–6500 (2015).

Jia, W., Jia, B., Qu, F. & Wu, X. Towards a highly efficient simulated sunlight driven photocatalyst: a case of heterostructured ZnO/ZnS hybrid structure. Dalton Transactions 42, 14178–14187 (2013).

Chen, T.-T., Chang, I. C., Yang, M.-H., Chiu, H.-T. & Lee, C.-Y. The exceptional photo-catalytic activity of ZnO/RGO composite via metal and oxygen vacancies. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 142, 442–449 (2013).

Yu, X. et al. ZnO@ZnS hollow dumbbells-graphene composites as high-performance photocatalysts and alcohol sensors. New Journal of Chemistry 36, 2593–2598 (2012).

Torabi, A. & Staroverov, V. N. Band Gap Reduction in ZnO and ZnS by Creating Layered ZnO/ZnS Heterostructures. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 6, 2075–2080 (2015).

Gao, X. X., Wang, J., Yu, J. L. & Xu, H. B. Novel ZnO-ZnS nanowire arrays with heterostructures and enhanced photocatalytic properties. Crystengcomm 17, 6328–6337 (2015).

Li, B. X., Wang, Y. F. & Wu, Y. L. Flower-Like ZnO/ZnS Heterostructures: Facile Synthesis, Structural Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity. Chinese Journal of Inorganic Chemistry 28, 417–424 (2012).

Ma, H. et al. Synthesis of visible light responsive ZnO–ZnS/C photocatalyst by simple carbothermal reduction. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 102, 417–423 (2011).

Gao, P. et al. One-Pot Hydrothermal Synthesis of Heterostructured ZnO/ZnS Nanorod Arrays with High Ethanol-Sensing Properties. Chemistry-a European Journal 18, 4681–4686 (2012).

Yu, X. L., Ji, H. M., Wang, H. L., Sun, J. & Du, X. W. Synthesis and Sensing Properties of ZnO/ZnS Nanocages. Nanoscale Research Letters 5, 644–648 (2010).

Huang, X. et al. Single crystalline wurtzite ZnO/zinc blende ZnS coaxial heterojunctions and hollow zinc blende ZnS nanotubes: synthesis, structural characterization and optical properties. Nanoscale 6, 8787–8795 (2014).

Baranowska-Korczyc, A. et al. Facile synthesis of core/shell ZnO/ZnS nanofibers by electrospinning and gas-phase sulfidation for biosensor applications. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 17, 24029–24037 (2015).

Neveux, L., Chiche, D., Bazer-Bachi, D., Favergeon, L. & Pijolat, M. New insight on the ZnO sulfidation reaction: Evidences for an outward growth process of the ZnS phase. Chemical Engineering Journal 181, 508–515 (2012).

Benton, O., Apollo, S., Naidoo, B. & Ochieng, A. Photodegradation of Molasses Wastewater Using TiO2-ZnO Nanohybrid Photocatalyst Supported on Activated Carbon. Chemical Engineering Communications 203, 1443–1454 (2016).

Ibhadon, A. O. & Fitzpatrick, P. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis: Recent Advances and Applications. Catalysts 3, 189–218 (2013).

Lonkar, S. P., Pillai, V., Abdala, A. & Mittal, V. In situ formed graphene/ZnO nanostructured composites for low temperature hydrogen sulfide removal from natural gas. Rsc Advances 6, 81142–81150 (2016).

Golsheikh, A. M., Lim, H. N., Zakaria, R. & Huang, N. M. Sonochemical synthesis of reduced graphene oxide uniformly decorated with hierarchical ZnS nanospheres and its enhanced photocatalytic activities. Rsc Advances 5, 12726–12735 (2015).

Zhang, Y. H., Zhang, N., Tang, Z. R. & Xu, Y. J. Graphene Transforms Wide Band Gap ZnS to a Visible Light Photocatalyst. The New Role of Graphene as a Macromolecular Photosensitizer. Acs Nano 6, 9777–9789 (2012).

Rabieh, S., Nassimi, K. & Bagheri, M. Synthesis of hierarchical ZnO-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites with enhanced adsorption-photocatalytic performance. Materials Letters 162, 28–31 (2016).

Zhang, Y. G. et al. ZnS nanoparticle-assisted synthesis and optical properties of ZnS nanotowers. Crystal Growth & Design 7, 1459–1462 (2007).

Wang, Z., Cao, S.-W., Loo, S. C. J. & Xue, C. Nanoparticle heterojunctions in ZnS-ZnO hybrid nanowires for visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Cryst Eng Comm 15, 5688–5693 (2013).

Hu, H. T., Wang, X. B., Liu, F. M., Wang, J. C. & Xu, C. H. Rapid microwave-assisted synthesis of graphene nanosheets-zinc sulfide nanocomposites: Optical and photocatalytic properties. Synthetic Metals 161, 404–410 (2011).

Paparazzo, E. On the interpretation of XPS spectra of metal (Pt, Pt-Sn) nanoparticle/graphene systems. Carbon 63, 578–581 (2013).

Li, X., Yu, J. G., Wageh, S., Al-Ghamdi, A. A. & Xie, J. Graphene in Photocatalysis: A Review. Small 12, 6640–6696 (2016).

Wang, G. et al. Synthesis and characterization of ZnS with controlled amount of S vacancies for photocatalytic H(2) production under visible light. Scientific Reports 5, 8544 (2015).

Schrier, J., Demchenko, D. O., Lin, W. & Alivisatos, A. P. Optical Properties of ZnO/ZnS and ZnO/ZnTe Heterostructures for Photovoltaic Applications. Nano Letters 7, 2377–2382 (2007).

Zhang, H., Lv, X. J., Li, Y. M., Wang, Y. & Li, J. H. P25-Graphene Composite as a High Performance Photocatalyst. Acs Nano 4, 380–386 (2010).

Zhang, N., Zhang, Y. H. & Xu, Y. J. Recent progress on graphene-based photocatalysts: current status and future perspectives. Nanoscale 4, 5792–5813 (2012).

Zhao, H. et al. Facile preparation of a ZnS/ZnO nanocomposite for robust sunlight photocatalytic H-2 evolution from water. Rsc Advances 5, 6494–6500 (2015).

Ummartyotin, S., Bunnak, N., Juntaro, J., Sain, M. & Manuspiya, H. Synthesis and luminescence properties of ZnS and metal (Mn, Cu)-doped-ZnS ceramic powder. Solid State Sciences 14, 299–304 (2012).

Feng, Y. et al. A ZnS nanocrystal/reduced graphene oxide composite anode with enhanced electrochemical performances for lithium-ion batteries. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 18, 30630–30642 (2016).

Zhai, T., Gu, Z., Fu, H., Ma, Y. & Yao, J. Synthesis of Single-Crystal ZnS Nanoawls via Two-Step Pressure-Controlled Vapor-Phase Deposition and Their Optical Properties. Crystal Growth & Design 7, 1388–1392 (2007).

Trajic, J. et al. Raman spectroscopy of ZnS quantum dots. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 637, 401–406 (2015).

Mari, B., Manjon, F. J., Mollar, M., Cembrero, J. & Gomez, R. Photoluminescence of thermal-annealed nanocolumnar ZnO thin films grown by electrodeposition. Applied Surface Science 252, 2826–2831 (2006).

Stroyuk, A. L., Kryukov, A. I., Kuchmii, S. Y. & Pokhodenko, V. D. Quantum Size Effects in Semiconductor Photocatalysis. Theoretical and Experimental Chemistry 41, 207–228 (2005).

Wu, C.-H. & Chern, J.-M. Kinetics of Photocatalytic Decomposition of Methylene Blue. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 45, 6450–6457 (2006).

Aslam, M. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of V2O5–ZnO composites for the mineralization of nitrophenols. Chemosphere 117, 115–123 (2014).

V, L. P. & Rajagopalan, V. A New Synergetic Nanocomposite for Dye Degradation in Dark and Light. Scientific Reports 6, 38606 (2016).

Lee, J.-E., Khoa, N. T., Kim, S. W., Kim, E. J. & Hahn, S. H. Fabrication of Au/GO/ZnO composite nanostructures with excellent photocatalytic performance. Materials Chemistry and Physics 164, 29–35 (2015).

Leary, R. & Westwood, A. Carbonaceous nanomaterials for the enhancement of TiO2 photocatalysis. Carbon 49, 741–772 (2011).

Wang, X. et al. Mechanism and process of methylene blue degradation by manganese oxides under microwave irradiation. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 160, 211–216 (2014).

Sheikh, M. U. D., Naikoo, G. A., Thomas, M., Bano, M. & Khan, F. Solar-assisted photocatalytic reduction of methyl orange azo dye over porous TiO2 nanostructures. New Journal of Chemistry 40, 5483–5494 (2016).

Marcano, D. C. et al. Improved Synthesis of Graphene Oxide. Acs Nano 4, 4806–4814 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) R&D Gas Subcommitte R&D. Authors also thank Samuel Stephen for TEM images, Dr. Vishwanath Kalyani, IIT-Mumbai for XPS analysis, and Dr. Sudhir Arbuj, C-MET, Pune for UV-DRS and PL measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P.L. and S.M.A. conceived the project idea and designed the experiment; S.P.L. and V.V.P. performed the experiments and data analysis. S.P.L. wrote the manuscript and S.M.A. revised it. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lonkar, S.P., Pillai, V.V. & Alhassan, S.M. Facile and scalable production of heterostructured ZnS-ZnO/Graphene nano-photocatalysts for environmental remediation. Sci Rep 8, 13401 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31539-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31539-7

This article is cited by

-

Impact of Cr/Gd and Cr/V co-doping on the physicochemical and photocatalytic behavior of CdS quantum dots

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2026)

-

Surface texture dependency of photocatalytic behavior of facile synthesized mesoporous ZnS-ZnO heterostructure under LED illumination

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

An Overview of Graphene-Based 2D/3D Nanostructures for Photocatalytic Applications

Topics in Catalysis (2025)

-

Facile synthesis of PVA-supported ZnS nano-cottons as recyclable catalyst for the efficient reduction of p-nitrophenol and photodegradation of solochrome dark blue under the sunlight irradiation

Discover Catalysis (2025)

-

Sustainable Synthesis of Zinc Oxide-Doped Graphene by Thermal Decomposition: A Game Changer in Indigo Carmine Removal from Water

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2025)