Abstract

Holevo capacity is the maximum rate at which a quantum channel can reliably transmit classical information without entanglement. However, calculating the Holevo capacity of arbitrary quantum channels is a nontrivial and computationally expensive task since it requires the numerical optimization over all possible input quantum states. In this paper, we consider discrete Weyl channels (DWCs) and exploit their symmetry properties to model DWC as a classical symmetric channel. We characterize lower and upper bounds on the Holevo capacity of DWCs using simple computational formulae. Then, we provide a sufficient and necessary condition where the upper and lower bounds coincide. The framework in this paper enables us to characterize the exact Holevo capacity for most of the known special cases of DWCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the fundamental tasks in the context of information theory is to compute the maximum rate at which information can be reliably transmitted1,2. Classical channels have the capability of transmitting classical information only. On the contrary, quantum channels are more rich in terms of communication tasks3,4. Trivially, quantum channels are capable of transmitting quantum information. However, due to the versatile nature and unique features of quantum mechanics, it is possible to associate multiple communication tasks with a quantum channel5. Thus, we have classical capacity, quantum capacity, private classical capacity, and entanglement-assisted classical capacity of a quantum channel. All of theses correspond to different information communication tasks6,7,8,9.

The calculation of various capacities involves an optimization task that is not easy to perform. For example, the capacity of a classical channel is given by a single letter formula—the mutual information between input and output of the channel—maximized over the probability distribution of the input random variable10. Efficient methods exist that can perform this maximization11,12. On the contrary, capacities (except the entanglement-assisted classical capacity) of a quantum channel are given in terms of regularization of asymptotically many channel uses. These regularized formulae are mathematically intractable in general and put forth an unsolvable optimization problem13. Simplification of these formulae is not possible due to the nonadditive and nonconvex natures of capacities of quantum channels14,15,16. The need of regularization, however, can be removed either (1) if the capacity of the channel is additive, or (2) if we restrict the optimization to be on the individual channel use. For example, unital qubit channels17 and entanglement breaking channels18 are known to be additive and thus their classical capacity can be computed without the need of regularization. Similarly, for the task of classical communication over a quantum channel, one can prohibit the use of inputs states correlated over multiple uses of the channel–effectively allowing optimization on the individual channel use only–to obtain a lower bound on the classical capacity of a quantum channel. This notion of capacity is known as the Holevo capacity. Even with such a simplification of the problem, the calculation remains considerably demanding. As a matter of fact, calculation of the Holevo capacity falls in the category of NP-complete problems15,19.

This multilayer difficulty has stimulated a good amount of research in the field of quantum information theory. Different researchers have taken different routes to accomplish this seemingly impossible task. For example, different definitions of capacities have been proposed20, analytical expressions for the special channels have been found21, and some bounds that are additive and easier to calculate have been computed22 to solve the problem of regularization. While for solving the difficulty of calculation, exploiting special properties of a given channel23, and methods that can approximate the capacity upto a fixed a posteriori error have been proposed24.

In this work we give easy to compute lower and upper bounds on the Holevo capacity of discrete Weyl channels (DWCs). Our employed approach involves modeling the DWC as a classical symmetric channel and using the existing results from the classical information theory to lower bound the Holevo capacity of a DWC. The upper bound is based on the majorization relation of any possible output state of a DWC with the most ordered state based on the channel parameters. We give a necessary and sufficient condition for which the two bounds coincide. We find that this condition is met for the known special cases (Pauli qubit channel, and the qudit depolarizing channel) of DWC and hence we can recover the exact capacity expression for these cases. Through numerical examples we show that the coincidence of two bounds is sufficient but not necessary for the lower bound to give exact capacity.

Discrete Weyl Channel

A quantum state ρ on the Hilbert space is a positive operator with unit trace (i.e., a density operator). We consider the Hilbert space of finite dimension d. The state is said to be pure if it has the form ρ = |ψ〉 〈ψ|. We usually denote a pure state simply by a ket e.g., |ψ〉, which is a column vector in the Hilbert space. A quantum channel \({\mathscr{N}}:{\boldsymbol{\rho }}\to {\mathscr{N}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }})\) is a completely positive trace preserving (CPTP) map transforming the input state ρ to an output state \({\mathscr{N}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }})\). The map can be specified in terms of Kraus operators {Ai} as \({\mathscr{N}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }})={\sum }_{i}\,{{\boldsymbol{A}}}_{i}{\boldsymbol{\rho }}{{\boldsymbol{A}}}_{i}^{\dagger }\) where \({\sum }_{i}\,{{\boldsymbol{A}}}_{i}^{\dagger }{{\boldsymbol{A}}}_{i}={{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{d}\) and Id is the identity operator on the d-dimensional Hilbert space. For a random unitary channel, it is possible to represent Kraus operators as \({{\boldsymbol{A}}}_{i}=\sqrt{{p}_{i}}{{\boldsymbol{B}}}_{i}\), such that the channel applies an operator Bi on the input state with the probability pi25.

Let \({{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}_{0}={{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{2}\) be the 2 × 2 identity matrix, and

be the Pauli matrices. The Pauli qubit channel, denoted by \({{\mathscr{N}}}_{{\rm{p}}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }})\), is then defined as

which is a random unitary channel.

Discrete Weyl operators are a non-Hermitian generalization of Pauli operators for dimension d26. A Weyl operator Wnm on the d-dimensional Hilbert space is defined as27

for \(n,\,m=\mathrm{0,}\,\mathrm{1,}\,\cdots ,\,d-1\); \(\omega =\exp (2\pi \iota /d)\); and |k〉 is the kth basis vector in the computational basis (for notational convenience, the indexing of entries of vectors and matrices start from 0). A general structure of a d-dimensional Weyl operator Wnm is shown in Fig. 1.

Property 1.

A Weyl operator Wnm, when applied on a d-dimensional vector α, up-shifts the entries of α by m locations and rotates ith entry (according to new indexing) by a phase of ωin. We refer to this property as shift and phase operation of Weyl operators.

Eigenvalues of a Weyl operator Wnm are given by (see supplementary material),

where \(s\in \{(mk-nj)\,{\rm{mod}}\,d\}\) for \(j,\,k=\mathrm{0,}\,\cdots ,\,d-1\). A schematic illustration for the Weyl operator W31 on a 4-dimensional Hilbert space is given in Fig. 2. Note that Weyl operators operating on a prime dimensional Hilbert space have d distinct eigenvalues (and we can simply state that \(s=\mathrm{0,}\,\mathrm{1,}\,\cdots ,\,d-1\)) except for W00. On the other hand, some Weyl operators of a composite dimension may have repeated eigenvalues. This repetition of eigenvalues restrains us from deriving general forms of our results directly. We circumvent this problem by first presenting our results for the Hilbert space of a prime dimension, and then show that an alternate formulation of our results can be applied to the case of a composite dimensional Hilbert space as well.

A DWC, denoted by \({{\mathscr{N}}}_{{\rm{dw}}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }})\), is a generalization of the Pauli qubit channel1, defined in terms of discrete Weyl operators as

where Wnm acts on the input state ρ with probability pnm.

The Holevo capacity of a quantum channel is defined as6,28

where pi is the a priori probability of input state ρi; \(S({\boldsymbol{\rho }})=-\,{\rm{Tr}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\,\mathrm{log}\,{\boldsymbol{\rho }})\) is the von Neumann entropy, and \({\mathscr{N}}({\boldsymbol{\rho }})\) is the output state produced by the action of channel \({\mathscr{N}}\) on the input state ρ. The Holevo capacity corresponds to the maximum rate of classical information when input states are restricted to be separable, i.e., the inputs of the channel are not entangled over multiple uses.

Lemma 1.

If the input state of a DWC operating on a d-dimensional Hilbert space is an eigenstate of a d-dimensional Weyl operator Wnm, then the output state is diagonal in the eigenbasis of Wnm.

Proof

. See Methods section.◽

As a consequence of the above Lemma, we can choose the set of input states to be d orthogonal eigenvectors of some Weyl operator Wnm, and measure the output in the eigenbasis of Wnm. The uncertainty at the output of the channel in this case is purely classical in nature. In this sense, a DWC is behaving as a classical channel, transitioning a distinguishable state into an unknown but perfectly distinguishable state. We completely characterize the simulated classical channel in terms of channel transition matrix in the following Proposition.

Proposition 1

A DWC of a prime dimension d with orthonormal eigenstates of W nm as the input states behaves as a classical symmetric channel with the following transition matrix

where

Proof.

See Methods section.◽

As an example, a DWC driven by the eigenstates of W21 with d = 3 is shown in Fig. 3. In this example, we have \({P}_{1}={p}_{00}+{p}_{21}+{p}_{12}\), \({P}_{2}={p}_{20}+{p}_{11}+{p}_{02}\), and \({P}_{3}={p}_{10}+{p}_{01}+{p}_{22}\).

Results

Based on the proposition 1, we give the following simple and natural lower bound on the Holevo capacity of a DWC:

Theorem 1

The Holevo capacity \(\chi ({{\mathscr{N}}}_{{\rm{dw}}})\) of the channel in (5) with a prime d is bounded as

where Tnm is the channel transition matrix of the (n, m) th symmetric channel obtained by fixing the eigenstates of Wnm as the signal states and \(H(\,\cdot \,)\) is the Shannon entropy.

Proof

. See Methods section.◽

The restriction on d to be a prime number is primarily because the repetition of eigenvalues of Wnm of a composite d does not allow us to construct the channel transition matrix Tnm. The following remark provides us an alternative approach to lower bound the Holevo capacity of DWC of any d.

Remark 1.

It is straightforward to show that \(H({\rm{row}}\,{\rm{of}}\,{{\boldsymbol{T}}}_{nm})=S({{\mathscr{N}}}_{{\rm{dw}}}(|\lambda \rangle \,{\langle \lambda |}_{nm}))\) when d is prime, where \(|\lambda \rangle {\langle \lambda |}_{nm}\) is the density matrix of any eigenstate of Wnm. Therefore, we can equivalently calculate

for prime d. Then, we can extend (10) to any d by replacing the optimization on any ρ in (20) with the optimization on the eigenstates of Wnm only.

Theorem 2.

Let us define a vector \({\boldsymbol{\zeta }}({\boldsymbol{p}})\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) such that

where the elements of \({{\boldsymbol{p}}}^{\downarrow }\) are the elements of vector \({\boldsymbol{p}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}^{2}}\) in descending order; the matrix \({\boldsymbol{S}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times {d}^{2}}\) is given by

where \({(\cdot )}^{T}\) denotes the transpose operation, and 1d and 0d are all-one and all-zero vectors of d elements, respectively. Then, the Holevo capacity of a DWC is

where \({\boldsymbol{p}}={[{p}_{00}{p}_{01}\cdots {p}_{nm}]}^{T}\), whose elements are probabilities associated with respective Weyl operators Wnm.

Proof.

See Methods section.◽

In a d-dimensional Hilbert space, d2 Weyl operators are defined whose indices are given in the form of 2-tuples, e.g., (i, j). We define a set \({\mathscr{W}}\) that contains all the d2 indices of defined Weyl operators. We call a set \({\mathscr{D}}\) a d-set if all its elements \({{\mathscr{D}}}_{i}\) for \(i=\mathrm{0,}\,\cdots ,\,d-1\) are non-overlapping d element subsets of \({\mathscr{W}}\)

where \({\mathscr{A}}{\subset }_{d} {\mathcal B} \) means that \({\mathscr{A}}\) is a d-element subset of \( {\mathcal B} \), \(\varnothing \) is the empty set, and \({\mathscr{A}}\cap {\mathcal B} \) gives a set whose elements are the common elements of \({\mathscr{A}}\) and \( {\mathcal B} \). In the d dimensional Hilbert space, there are

different possible d-sets, where

are the binomial coefficients.

A d-set \({\mathscr{D}}\) whose all elements \({{\mathscr{D}}}_{t}\) satisfy the property

for some n, m, and some constants kt is called an achievable d-set. For example

is an achievable d-set for (n, m) = (2, 1) but

is a d-set which is not achievable.

Theorem 3.

We arrange the elements of p in nonincreasing order and collect the indices of pnm while preserving the order to form a d-set. The bounds of Theorem 1, and Theorem 2 coincide if and only if (resp. only if) the obtained d-set is achievable and d is a prime number (resp. a composite number).

Proof.

See Methods section.◽

Remark 2.

If the two bounds coincide, we have

However, the converse is not true as will be shown by the numerical examples in the next section.

Discussion

An efficient approximation for the capacity of classical-quantum channels has previously been discussed without exploiting any special properties of a given channel24. For example, it takes 40,154 seconds in order to approximate the Holevo capacity of a Pauli qubit channel with a posteriori error of 1.940 × 10−3. In contrast to existing methods, the average time to calculate the (lower) bound in this paper is of the order 10−4 seconds even for large d by virtue of the use of special properties of DWCs.

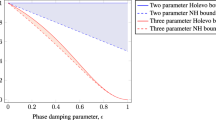

We have strong numerical evidence that the lower bound is tighter and is saturated more often even when the two bounds do not coincide, as shown in the Fig. 4(a–c) where the upper (χUB) and the lower (χLB) bounds (normalized by log2(d)) are plotted for 1200 random channel realizations for d = 3, 4, and 5, respectively. In these figures, Holevo capacity by using23

with the optimization performed via genetic algorithm (χGA) is also presented. Comparison of χLB, χUB, and χGA shows that the frequency of coincidence of two bounds as well as the frequency of the saturation of the lower bound is higher for the case of d = 3.

Our bounds not only ease the requirement of optimization for the calculation of tight bounds for a general DWC, but also allows to recover the analytic expressions for the special cases of DWC. For example, here we recover the analytic expression for the classical capacity of a qudit depolarizing channel using the approach developed above. A quantum depolarizing channel transforms an input state to the output state according to the following map

where \({\boldsymbol{\pi }}={{\boldsymbol{I}}}_{d}/d\) is the maximally mixed state on the output Hilbert space. In terms of Weyl operators,

Thus, we can rewrite equation (21) as

Therefore

which shows that all d-sets (whether achievable or not) are equivalent in terms of summation of pnm over the elements \({{\mathscr{D}}}_{i}\). Therefore, we can choose an ordering of pnm such that the condition of Theorem 3 is satisfied and we can use equation (13) to calculate the Holevo capacity. From equation (21) and the output vector of \({\boldsymbol{\zeta }}({\boldsymbol{p}})=({r}_{0},\,{r}_{1},\,\cdots ,\,{r}_{d})\), we see that

Thus, the Holevo capacity \(\chi ({{\mathscr{N}}}_{{\rm{d}}})\) of this channel is

which is equal to the classical capacity of the quantum depolarizing channel21.

Additionally, it is easy to see that for a Pauli qubit channel (d = 2), there are 3 possible d-sets which are all achievable. Therefore, both bounds are exact for the Pauli qubit (and all its special cases) channel. With simple algebraic manipulations one can obtain the analytic expressions for the capacities of any of the special cases of the Pauli qubit channel24.

From Theorem 3, we can also define special channels for which the two bounds always coincide. This approach gives us a class of quantum channels whose exact Holevo capacity can readily be calculated. We define two such channels here and call them one-parameter depolarizing-like, and two-parameter depolarizing-like channels, respectively.

The one-parameter depolarizing-like channel is defined as

whose exact Holevo capacity is same as (26) with the depolarizing parameter ξ.

The two-parameter depolarizing-like channel is

where \(0\le \eta ,\,\kappa \le \mathrm{1,}\,{\rm{and}}\,1\le \eta +\kappa \le 2\). This channel is a further generalization of the one-parameter depolarizing-like channel. The exact Holevo capacity of this channel can readily be calculated by Theorem 3.

In this work we modeled a DWC as a classical symmetric channel for the task of classical communication. Through this modeling, we presented a simple to compute lower bound on the Holevo capacity of a given DWC of an arbitrary dimension. We also gave an intuitive upper bound which coincides with the lower bound under a certain condition. This (sufficient and necessary for a prime d, and necessary for a composite d) condition, however, is not frequently met despite the frequent convergence of the lower bound to the actual Holevo capacity as shown by the numerical examples. The lower bound was derived by noting the similarity of a quantum channel with a classical channel. An interesting future direction is to find similar cases where the results of classical information theory (which is more mature despite being a special case of quantum information theory) can be applied on the problems of quantum information theory with a little or no modification. Similarly, based on the equality of upper and lower bounds, one can define special channels for which these bounds always coincide. Such characterization of quantum channels can give us a class of channels whose exact Holevo capacity can readily be calculated.

Methods

Proof of Lemma 1

Since the DWC is a random unitary channel, the output of the channel is merely the state obtained by randomly applying one of the d2 Weyl operators on the input. Thus, we need to show that operation of Wij on any eigenstate of Wnm results into an eigenstate of Wnm.

Let

be a normalized eigenvector of Wnm with the corresponding eigenvalue λ. From the eigenvalue relation \({{\boldsymbol{W}}}_{nm}|\lambda \rangle =\lambda |\lambda \rangle \), and due to the property 1, we get the following relation among the entries of vector of (29)

where the eigenvalues λ are equidistant points on the unit circle (see Fig. 2). Since we have obtained this relation from the condition of eigenvector, any vector satisfying above relation will be an eigenvector of Wnm.

Now let us consider the effect of any Wij on the vector of (29). To this end, we let \({{\boldsymbol{W}}}_{ij}|\lambda \rangle =|\beta \rangle \), and recall property 1 again to write

i.e., the kth entry of \(|\beta \rangle \) is \({\omega }^{ki}{\alpha }_{(j+k){\rm{mod}}d}\).

If the elements of \(|\beta \rangle \) exhibit a similar relation as (30), \(|\beta \rangle \) is also an eigenvector of Wnm. Repeated use of (30) gives the following relation between the entries of \(|\beta \rangle \)

which essentially bears the same form as (30); because \(\lambda {\omega }^{mi-nj}\) is another eigenvalue of Wnm. Hence the vector \(|\beta \rangle ={{\boldsymbol{W}}}_{ij}|\lambda \rangle \) is an eigenvector of Wnm. Since the output state is a statistical mixture of orthonormal eigenstates of Wnm, it is diagonal in the same basis, i.e., in the eigenbasis of Wnm.

Proof of Proposition 1

Let the input state be an eigestate |λ〉 of Wnm corresponding to the eigenvalue λ. From the proof of Lemma 1, the application of Wij transforms the input state to the eigenstate of Wnm corresponding to the eigenvalue \(\lambda {\omega }^{mi-nj}\). Since \(\omega =\exp (2\pi \iota /d)\), \({\omega }^{mi-nj}\) is always from the set \(\{{\omega }^{0},\,{\omega }^{1},\,\cdots ,\,{\omega }^{d-1}\}\). Therefore, we can define,

as the transition probability of |λ〉 to the orthogonal state \(|\lambda {\omega }^{k-1}\rangle \). We can define the complete set of transition probabilities Pk, for \(k=\mathrm{1,}\,\mathrm{2,}\,\cdots ,\,d\) only if Wnm does not have any repeated eigenvalues which is guaranteed only if d is prime and \((n,\,m)\ne (\mathrm{0,}\,0)\) (note the similarity between \({\omega }^{mi-nj}\) and the expression for s in the definition of eigenvalues).

Furthermore, we notice that the rows of Tnm are permutations of each other and its columns are permutation of each other. Therefore, Tnm in (7) defines a classical symmetric channel.

Proof of Theorem 1

From proposition 1 we know that in this setting DWC acts as a classical symmetric channel. Since the capacity of a symmetric channel with d inputs and outputs is given by2

and we have restricted our input states to be from the eigenstates of Weyl operators, thus

where the condition \((n,\,m)\ne \mathrm{(0,}\,\mathrm{0)}\) along with the condition on d to be prime ensures that we can model the given DWC as a classical symmetric channel with the channel transition matrix Tnm by virtue of Proposition 1.

Proof of Theorem 2

For a vector \({\boldsymbol{x}}=({x}_{1},\,{x}_{2},\,\cdots ,\,{x}_{n})\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{n}\), we denote xi in non-increasing order as

and denote the vector \({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{\downarrow }=({x}_{[1]},\,{x}_{[2]},\,\cdots ,\,{x}_{[n]})\) of elements of x rearranged in nonincreasing order. We denote by \({\boldsymbol{x}}\,\prec \,{\boldsymbol{y}}\) and say x is majorized by y if

with strict equality when k = n. For two Hermitian operators A and B, we denote \({\boldsymbol{A}}\,\prec \,{\boldsymbol{B}}\) if \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}({\boldsymbol{A}})\,\prec \,{\boldsymbol{\lambda }}({\boldsymbol{B}})\), where \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}({\boldsymbol{A}})\) is the vector of eigenvalues of A.

Let γ be the optimal input state, then the Holevo capacity of a DWC is23

We can rewrite (13) as

where \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\) is some state with the eigenvalues qi given by the elements of \({\boldsymbol{\zeta }}({\boldsymbol{p}})\). Comparing (37) and (38), our claim simplifies to

or from the Schur concavity of von Neumann entropy29

where

Eigendecomposition of \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\) can be written as

where \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\), and \({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}_{k}\) are some pure states; \({\rm{Tr}}\{{{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}_{i}{{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}_{j}\}=1\) if i = j, and 0 otherwise; and Sk are some unitary operators defined by the relation \({{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{k}{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{k}^{\dagger }={{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}_{k}\). We note that we are free to choose any \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\) as long it has eigenvalues qk. This freedom translates to the choice of \({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}_{k}\), and hence to Sk.

Equation (40) is true if and only if 30, [Theorem 5]

for some probability vector s with elements si and some unitary matrices Ui. We write

where we can write \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}=V{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}{{\boldsymbol{V}}}^{\dagger }\) because both \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\) and γ are pure states, and we can obtain \({r}_{ik}={p}_{ik}\) due to30, [Theorem 4]. Without a loss of generality we can assume both \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}\) and γ to be the basis states of a basis set each, i.e., \({\boldsymbol{\sigma }}={{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}_{0}\in { {\mathcal B} }_{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}\), and \({\boldsymbol{\gamma }}={{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}}_{0}\in { {\mathcal B} }_{{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}}\). There is also no loss of generality in assuming \({ {\mathcal B} }_{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}\) to be the computational basis. Under these assumptions, the unitary V is the change of basis unitary from \({ {\mathcal B} }_{{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}}\) to the computational basis, i.e.,

We need to find Ui, and Sk, such that

or

Choosing

satisfies the above product (the indexing of j and of \({{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}}_{j}\) is arbitrary except for j = 0), as well as the orthogonality of \({{\boldsymbol{\rho }}}_{k}={{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{k}{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}{{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{k}^{\dagger }\). Therefore, (13) is an upper bound on the Holevo capacity of a DWC.

Proof of Theorem 3

We first observe that the condition on the summation in (8) for the lower bound, and the condition on a d-set to be achievable (16) are essentially the same and result in the same d-element partitioning and ordering of pnm. Thus, in a prime dimension d, every achievable d-set corresponds to a classical symmetric channel that can be simulated by DWC for some n, m.

On the other hand, the upper bound is obtained by ordering the elements of pnm in a nonincreasing order. Therefore, the achievability of the d-set formed by the indices of pnm when the pnm are arranged in a nonincreasing order is sufficient for the existence of a simulated classical symmetric channel of prime dimension that achieves the upper bound. Similarly, since the correspondence of achievable d-sets to a simulated classical symmetric channel is bijective, therefore the conincidence of two bounds necessarily implies the achievability of the d-set formed above.

For a composite d, the correspondence between the simulated classical symmetric channel to the achievable d-sets is injective-only. Therefore the above condition is necessary but no longer sufficient for the coincidence of two bounds.

References

Wilde, M. M. Quantum Information Theory, 2 edn. (Cambridge University Press, UK 2017).

Cover, T. M. & Thomas, J. A. Elements of Information Theory, 2 edn. (John Wiley & Sons, USA 2012)

Ur Rehman, J., Qaisar, S., Jeong, Y. & Shin, H. Security of a control key in quantum key distribution. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 31, 1750119, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217984917501196 (2017).

Qaisar, S., Ur Rehman, J., Jeong, Y. & Shin, H. Practical deterministic secure quantum communication in a lossy channel. Progr. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2017, 041A01 (2017).

Zaman, F., Jeong, Y. & Shin, H. Counterfactual Bell-state analysis. Sci. Rep. 8, 14641 (2018).

Holevo, A. S. The capacity of the quantum channel with general signal states. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 44, 269–273 (1998).

Devetak, I. The private classical capacity and quantum capacity of a quantum channel. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 51, 44–55 (2005).

Bennett, C. H., Shor, P. W., Smolin, J. A. & Thapliyal, A. V. Entanglement-assisted capacity of a quantum channel and the reverse Shannon theorem. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 48, 2637–2655 (2002).

Bennett, C. H., Shor, P. W., Smolin, J. A. & Thapliyal, A. V. Entanglement-assisted classical capacity of noisy quantum channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 3081–3084 (1999).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal 27, 379–423 (1948).

Blahut, R. Computation of channel capacity and rate-distortion functions. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 18, 460–473 (1972).

Arimoto, S. An algorithm for computing the capacity of arbitrary discrete memoryless channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 18, 14–20 (1972).

Cubitt, T. et al. Unbounded number of channel uses may be required to detect quantum capacity. Nat. Commun. 6, 6739 (2015).

Smith, G. & Yard, J. Quantum communication with zero-capacity channels. Science 321, 1812–1815 (2008).

Elkouss, D. & Strelchuk, S. Nonconvexity of private capacity and classical environment-assisted capacity of a quantum channel. Phys. Rev. A 94, 040301 (2016).

Hastings, M. B. Superadditivity of communication capacity using entangled inputs. Nat. Phys. 5, 255–257 (2009).

King, C. Additivity for unital qubit channels. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4641–4653 (2002).

Shor, P. W. Additivity of the classical capacity of entanglement-breaking quantum channels. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4334–4340 (2002).

Beigi, S. & Shor, P. W. On the complexity of computing zero-error and Holevo capacity of quantum channels. arXiv:0709.2090 (2008).

Winter, A. & Yang, D. Potential capacities of quantum channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 62, 1415–1424 (2016).

King, C. The capacity of the quantum depolarizing channel. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 49, 221–229 (2003).

Fukuda, M. & Gour, G. Additive bounds of minimum output entropies for unital channels and an exact qubit formula. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 63, 1818–1828 (2017).

Cortese, J. Holevo-Schumacher-Westmoreland channel capacity for a class of qudit unital channels. Phys. Rev. A 69, 022302 (2004).

Sutter, D., Sutter, T., Esfahani, P. M. & Renner, R. Efficient approximation of quantum channel capacities. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 62, 578–598 (2016).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition, 10th edn. (Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA 2011).

Bertlmann, R. A. & Krammer, P. Bloch vectors for qudits. J. Phys. A 41, 235303 (2008).

Weyl, H. Quantenmechanik und gruppentheorie. Zeitschrift für Physik 46, 1–46 (1927).

Schumacher, B. & Westmoreland, M. D. Sending classical information via noisy quantum channels. Phys. Rev. A 56, 131–138 (1997).

Datta, N. & Ruskai, M. B. Maximal output purity and capacity for asymmetric unital qudit channels. J. Phys. A Math Gen. 38, 9785 (2005).

Nielsen, M. A. & Vidal, G. Majorization and the interconversion of bipartite states. Quantum Information & Computation 1, 76–93 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2016R1A2B2014462) and ICT R&D program of MSIP/IITP [R0190-15-2030, Reliable crypto-system standards and core technology development for secure quantum key distribution network].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.R. contributed the idea. J.R., J.S.K. and Y.J. developed the theory. H.S. improved the manuscript and supervised the research. All the authors contributed in analyzing and discussing the results and improving the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

ur Rehman, J., Jeong, Y., Kim, J.S. et al. Holevo Capacity of Discrete Weyl Channels. Sci Rep 8, 17457 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35777-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35777-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

On capacity of quantum channels generated by irreducible projective unitary representations of finite groups

Quantum Information Processing (2022)

-

Measurement-Based Quantum Correlations for Quantum Information Processing

Scientific Reports (2020)