Abstract

Theoretical advances in science are inherently time-consuming to realise in engineering, since their practical application is hindered by the inability to follow the theoretical essence. Herein, we propose a new method to freely control the time, cost, and process variables in the fabrication of a hybrid featuring Au nanoparticles on a pre-formed SnO2 nanostructure. The above advantages, which were divided into six categories, are proven to be superior to those achieved elsewhere, and the obtained results are found to be applicable to the synthesis and functionalisation of other nanostructures. Furthermore, the reduction of the time-gap between science and engineering is expected to promote the practical applications of numerous scientific theories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, although the boundaries of the academic area do not seem to be important, a clear-cut borderline separates pure science1,2, which explores the principles of nature, from applied engineering3,4, which deals with real-life processes. This separation largely reflects the corresponding difference in the utilised approaches, highlighting the fact that the application of new theories to real-world problems is difficult and time-consuming. For this reason, scientific heritage newly published every day is often discarded without actually being phenomenologically expressed. On the contrary, our daily life presents numerous strange phenomena that cannot be scientifically explained because of the lack of a proper academic background. That is, there may be cases of a theory not backed by experimental results or results not explained by any theory. As mentioned above, science and engineering can be viewed to be in a state of temporal hysteresis, and the search for ways of narrowing the corresponding time gap should therefore be regarded as a task of high significance. For example, Shi et al. reported the hetero-structured AgBr/ZnO photocatalyst, but their synthesis requires long reaction times and complex multi-step processes5. Ellis et al. also proposed the morphology control of hydrothermally prepared LiFePO4 with long reaction times and post heat treatment processes6. In other words, engineering techniques that can easily and economically confirm competitive scientific theories are shortcuts that can reduce the time cost of the practical application of science and achieve unique and meaningful results. Unluckily, because of the atmosphere that emphasises originality in research, one tends to think that only complicated and difficult-to-perform experiments can produce unique results. However, the reason why we cannot conclude that it is preconceived is that many of the results have received good evaluation in the meantime. For example, when studies on various nanostructures7,8,9,10 performed so far are divided into those dealing with morphology11,12, crystallography13,14, and elemental composition15,16 control, one can recognise that these investigations have a certain research value when the desired shape, microstructure, or function has been fully achieved. In this case, the employed raw materials and equipment are costly, the use of in-house-made equipment precludes verification in other laboratories, the experiment condition that was different from the existing experiment was exactly met in the repeated experiment, and technological differences related to the use of high-end analytical equipment are rarely considered. In other words, the outcomes of such experiments emphasise specificity rather than generality, and consequently require much time to be verified by engineering in real life, i.e., in such cases, one can only imply that a new theory can be realised. Herein, we introduce new processing advantages to easily fabricate a heterogeneous structure by attaching Au particles to pre-formed SnO2 nanostructures and compare the advantages of our work with the disadvantages of existing works in six representative categories used in science/engineering fields. The proposed method allows one to induce nucleation and growth in nanostructures in a shorter time than in the case of other synthesis/deposition techniques. Moreover, thermal energy injection allows the phase change and composition to be relatively easily altered, and the developed technique also allows one to easily change the shape and microstructure of pre-formed nanostructures, which is attributed to energy injection variation with temperature and holding time. Thus, in contrast to the existing principle of one-to-one matching, which assumes that one factor depends on one process variable, the described technique utilises a new one-to-many matching concept, allowing one to simultaneously control multiple factors with one process variable.

Result and Discussion

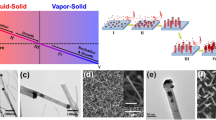

Figure 1 shows Au particle–decorated SnO2 nanostructures prepared under various experimental conditions. As is well known17,18, smooth and long SnO2 nanowires can be easily synthesised by thermal evaporation of Sn powder in an oxygen-containing atmosphere. Herein, the thickness of SnO2 nanowires ranged from 20 to 120 nm, and their length ranged from several tens to several hundred μm (Fig. 1a–c). However, when a 5-s energy pulse was applied to SnO2 nanowires that had previously been exposed to HAuCl4⋅4H2O/(CH3)2CHOH, the originally smooth surface of SnO2 nanowires got covered by Au particles and therefore became rough. The spherical Au particles attached to nanowires had a size of roughly 100–300 nm and were in a discrete state (Fig. 1d–i). Specifically, these particles did not aggregate to lower their surface energies and existed independently at regular intervals, which was ascribed to the fact that the thermal energy applied to SnO2 nanowires was not concentrated in a narrow region adjacent to nanowires but was uniformly dispersed in space. In other words, it was concluded that the applied thermal energy allowed the rate of nucleation to be held constant at all points of SnO2 nanowires. Thus, it could be said that this simultaneous energy injection was different from the general mechanism of nucleation and growth in the local region of interest. Only morphologically, Au-decorated SnO2 nanostructures can be prepared in any number of ways. However, most of these methods refrain from instantaneous processing to increase the cross-sectional area and require various pre- and post-processing techniques19,20,21. For example, Kim et al. synthesised noble metal–decorated SnO2 nanowires using thermal activation and employed the large cross-sectional area of these nanoparticles to detect noxious gases22. Wu et al. suggested that hydrothermally prepared hollow hybrid Au-SnO2 nanostructures can be utilised in photocatalysis application23, with advantages such as environmentally friendly solution-basis, low-cost, and surfactant-free. Bing et al. used a rational combinational multi-step synthetic route to prepare Au-loaded SnO2 hollow multi-layered nanosheets, composed of numerous nanoparticles as structural subunits24. Furthermore, although previous reports could realise nanocomposite structures of the abovementioned morphology25,26, they remain inferior in terms of speed, accuracy, yield, and economy, i.e., accessibility. For example, Lai et al. realised heterogeneous nucleation sites using a template with a low vaporisation point and fabricated nanobeads by subsequent template removal at high temperatures27. Some studies suggested that Pd-functionalised nanostructures can be formed by post-heat treatment and/or electron beam irradiation, without the involvement of extra precursors, because extra energy itself facilitates nucleation at an energy lower than that of homogeneous nucleation28,29. However, in the two cases mentioned above, there is no way to control nanowire parameters until the end stage, since metal particle nuclei are formed on the metal oxide before or during synthesis. That is, if the desired metal-decorated nanowires are not obtained, the experiment needs to be re-started from the very beginning. In contrast, our method relies on simultaneous annealing, allowing one to rapidly functionalise existing SnO2 nanowires in the desired way. This advantage cannot be found in any other post-processing technique, and one can therefore say that in addition to the abovementioned five advantages (speed, accuracy, yield, economy, and accessibility), our method also guarantees stability.

Typical SEM and TEM images of SnO2 nanowires formed by conventional thermal evaporation and of Au particles formed on SnO2 nanowires by flame chemical vapour deposition. (a) SEM image of bare SnO2 nanowires with a smooth surface; (b) low-magnification and (c) high-magnification SEM images of Au-SnO2 hybrid nanostructures; (d–i) variable-magnification TEM images of Au-SnO2 nanostructures of different shapes.

As shown in Fig. 1d–i, even though rugged Au particles were commonly observed on the originally smooth SnO2 nanowires, bigger Au spheres were sometimes formed on the surface of certain SnO2 nanowires through interfacially controlled spherical growth30. The above figures indicate no change in the morphology of Au-decorated nanowires; however, even in a localised region, the size of Au particles produced on nanowires tended to decrease with increasing time of thermal energy injection in that region. This behaviour was ascribed to the role of injected heat energy in inducing simultaneous nucleation over a large area, so that the effect of growing the nucleated first in a momentary difference is relatively insufficient. Therefore, as the retention time of energy injection at each point increased, the distance between Au particles generated in the nanowire decreased, while the density of Au particles produced at a fixed length increased. These results are in stark contrast with the fact that after nucleation, the rapid growth of nanostructures is commonly controlled by the rate of constituent atom diffusion31.

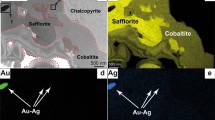

The above finding indicates that the increase of supplied energy amount with increasing heating time is related to the reduction of SnO2 accompanied by the formation of Au (Fig. 2). Thus, even for Au-decorated SnO2 of the same type, the reduction gradient is determined by the energy injection time (heating time). To investigate the degree of reduction, all samples were subjected to elemental mapping (Fig. 2a–d) and EDX (Fig. 2e–h) measurements, which revealed that the Sn:O ratio was different in nanowires and Au particles, as described above. In SnO2 nanowires, Au was not observed at all (Fig. 2e,f), but Sn and O were detected together with Au in the particle region (Fig. 2g,h). That is, the precipitation of Au and the reduction of SnO2 occurred simultaneously. This behaviour probably reflects the fact that when the Au solution was pushed to one side to become a particle as a result of energy supply, a part of the SnO2 nanowire surface was exposed and lost O because of the effect of direct energy injection. Thus, one has only started exploring the applications of these two effects, which are believed to have much scientific and engineering potential.

Zone composition of Au-SnO2 hybrid nanostructures identified by elemental mapping and EDX. (a–d) Distributions of Sn, O, and Au in a typical Au-decorated SnO2 nanowire; (e,f) contents of Sn and O in a SnO2 nanowire determined excluding Au particles; (g,h) contents of Sn, O, and Au in a Au particle excluding the SnO2 nanowire.

For each sample, the crystal phase composition and microstructure were verified by XRD (Fig. 3a) and TEM (Fig. 3b–g), respectively. Bare SnO2 nanowires were shown to have a tetragonal structure32, and peaks at 2θ = 26.61°, 33.89°, 37.95°, 38.97°, and 42.63° were in good agreement with reflections from (110), (101), (200), (111), and (210) planes of tetragonal SnO2, respectively (JCPDS No. 41–1445) (Fig. 3a)33. Peaks at 2θ = 38.18° and 44.39° were ascribed to reflections from the (111) and (200) planes of Au (JCPDS No. 04–0784), respectively34 (Fig. 3a). On the other hand, for samples prepared by applying thermal energy to bare SnO2 nanowires, we observed a change of SnO2 peak intensity and the appearance of new peaks. As described above, a reduction of SnO2 to Sn may occur under the employed conditions, which may result in the formation of non-equilibrium SnOx (0 < x < 2) phases (Fig. 3b–g). Although these peaks did not exactly match those in JCPDS cards because of the non-equilibrium nature of the former, such chemical changes could be sufficiently inferred from the shift of the (101) peak of pre-formed SnO2 to the (101) peak of Sn. At this time, a SnO2 layer was detected on the surface of SnO2 nanowires (Fig. 3d,f) and on the surface of Au particles (Fig. 3e). However, interplanar spacings of unbalanced compositions could be observed with proceeding partial reduction. In other words, no crystal phases except for those of SnO2 and Au were observed by XRD, although HRTEM line profiling indicated that the surface profiles of SnO2 or Au could change. This means that the energy supplied to the existing SnO2 nanowires was sufficient for SnOx to form on the Au surface (Fig. 3d–g).

Crystallinity and microstructure of several parts of Au-decorated SnO2 nanostructures. (a) XRD spectrum of Au-SnO2 mixture; (b,c) HRTEM images acquired at the interface between a Au particle (dark region) and a SnO2 nanowire (white region); (d) interplanar spacing showing the reduction of SnO2 to Sn on the surface of SnO2 nanowire; (e) interplanar spacing of SnO2-based layers formed on the Au particle surface; (f) interplanar spacing confirming the reduction of SnO2 to Sn, measured on the other surface of the SnO2 nanowire; (g) interplanar spacing confirming the reduction of SnO2 to Sn, measured inside the SnO2 nanowire.

The efficiency of making Au-SnO2 should be further objectified to allow the clear application of the competitiveness of the new method and its difference from the existing techniques. Consequently, the process methods were evaluated using six parameters (Tables 1, 2, S1 and S2), namely the employed precursor, equipment, pre- and post-treatment, temperature, time, and vacuum35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66. First, the new processing technique was found to be applicable to all materials regardless of their type. Second, while the previously used equipment occupies much space, requiring additional equipment to achieve the special purpose, our processing technology is not affected by location and does not involve the utilisation of useless accessories. Third, researches conducted so far, especially those requiring pre-processing such as templating and post-processing such as heat treatment, have often involved supplementary procedures to address the difficulty of direct synthesis and deposition, whereas our high-efficiency method does not require any pre- or post-processing. Fourth, in previous methods, the temperature had to be maintained within the range of at least 500 to 1000 °C for a long time to adjust the synthesis temperature of heterogeneous materials, whereas our method instantaneously provides a temperature of 1300 °C. Fifth, our process is operated on a timescale of seconds and is clearly different from other processes operated on the time scales of minutes or even hours, allowing one to control instantaneous processing conditions on the spot to match material properties. Sixth, conventional synthesis and deposition equipment requires the use of variable (low to ultra-high) vacuum depending on the specific case, whereas our technique does not require additional vacuum conditions, since it can be operated under atmospheric pressure. There may be many other classification criteria, but it seems clear that the above six advantages provide overwhelming evidence of the superiority of our method.

As mentioned above, differences between science and engineering inevitably result in the need for a certain time period to achieve coincidence. In most cases, a theory is first established, and the corresponding time-saving potential is evaluated in the next step. Therefore, it is meaningful to find a new method allowing one to control several variables through a simple experiment, which can simplify the whole process but produce various results. In the meantime, we have invested a lot of time and money in the synthesis and functionalisation of new materials with novel properties. Thus, the know-how to produce the desired results with this simple method can be applied to other materials in the same way, and the search for even simpler and more powerful derivation methods should not be stopped.

Conclusion

A new method of synthesising SnO2 and converting it to a different standard has been proposed. This method allows one to relatively easily control the parameters of Au-decorated SnO2 nanowires using thermal energy, i.e., the growth factors for each sample can be freely controlled depending on the given materials and processing time. Specifically, the reaction proceeds from a homogeneous structure to a heterogeneous structure, or from a stoichiometric structure to a non-stoichiometric structure, depending on the amount of applied energy. The trend of this transition is also consistent with the results of SEM, XRD, and TEM analyses. This seemingly ordinary process technology has proven to be overwhelmingly superior in terms of precursor, equipment, pre- and post-treatment, temperature, time, and vacuum. From an energy point of view, all experimentation with science/engineering bases relies on the idea of making a difference in energy or eliminating the energy difference. Thus, the ability to achieve a variety of effects by reducing the number of process variables and simply adjusting them should substantially contribute to reducing the congenital time gap between science and engineering.

Methods

To prepare SnO2 nanostructures, Sn powder (1 g; Daejung Co., 99.9%) was placed in an alumina boat of a thermal evaporation furnace. The silicon substrate with 3-nm Au was placed upside down on the alumina boat to create conditions facilitating the adsorption of Au onto the substrate upon vaporisation. The temperature was raised to 900 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min, and an O2-Ar mixture (97:3) was flown at a pressure of 2 Torr for 1 h at 900 °C.

Gold Chloride hydrate 99.995% (HAuCl4·4H2O (0.23 g, 99.995%) and 2-propanol (10 g, 99.5%) were well mixed, and 3 mL of the mixture was dropped on the substrate part where the SnO2 nanowires were to be synthesised. Thereafter, a flame with a temperature of 1300 °C was applied for 5 s in the standby state using a special flame chemical vapour deposition (FCVD) technique.

Morphology was probed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Hitachi S-4200, Hitachi) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-2100F, JEOL), crystallinity was probed by X-ray diffraction (XRD; Philips X’pert diffractometer, Philips) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), while elemental composition was probed by XRD, elemental mapping, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX).

Data availability

All the data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Engel, T. & Reid, P. Thermodynamics, statistical thermodynamics, and kinetics books a la carte edition (4rd Edition). (Pearson, 2018).

Hobson, A. Physics: concepts and connections. (Pearson, 2009).

Pahari, A. & Chauhan, B. Engineering chemistry. (Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2007).

Rajkiewicz, M. Chemical and Applied Engineering Materials: Interdisciplinary Research and Methodologies. (CRC Press, 2015).

Shi, L., Liang, L., Ma, J. & Sun, J. Improved photocatalytic performance over AgBr/ZnO under visible light. Superlattices Microstruct. 62, 128–139 (2013).

Ellis, B., Kan, W. H., Makahnouk, W. R. M. & Nazar, L. F. Synthesis of nanocrystals and morphology control of hydrothermally prepared LiFePO4. J. Mater. Chem. 17, 3248–3254 (2017).

Brown, A. J. et al. Interfacial microfluidic processing of metal-organic framework hollow fiber membranes. Sci. 345, 72–75 (2014).

Jana, S., de Frutos, M., Davidson, P. & Abecassis, B. Ligand-induced twisting of nanoplatelets and their self-assembly into chiral ribbons. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701483 (2017).

Nair, A. S. & Pathak, B. Computational Screening for ORR Activity of 3d Transition Metal Based M@Pt Core–Shell Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 3634–3644 (2019).

Ramesh, S., Karuppasamy, K., Kim, H.-S., Kim, H. S. & Kim., J.-H. Hierarchical Flowerlike 3D nanostructure of Co3O4@MnO2/N-doped Graphene oxide (NGO) hybrid composite for a high-performance supercapacitor. Sci. Rep. 8, 16543 (2018).

Ji, J. et al. Guanidinium-based polymerizable surfactant as a multifunctional molecule for controlled synthesis of nanostructured materials with tunable morphologies. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 19124–19134 (2017).

Li, Y. & Huang, Y. Morphology‐controlled synthesis of platinum nanocrystals with specific peptides. Adv. Mater. 22, 221921–1925 (2010).

Sharifi, T. et al. Impurity-controlled crystal growth in low-dimensional bismuth telluride. Chem. Mater. 30, 6108–6115 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Artificial compound eyes prepared by a combination of air-assisted deformation, modified laser swelling, and controlled crystal growth. ACS Nano 13, 114–124 (2019).

Mao, Y. & Wong, S. S. Composition and shape control of crystalline Ca1–xSrxTiO3 perovskite nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 172, 194–2199 (2005).

Tongying, P. et al. Control of elemental distribution in the nanoscale solid-state reaction that produces (Ga1–xZnx)(N1–xOx) nanocrystals. ACS Nano 11, 8401–8412 (2017).

Shin, G. et al. SnO2 nanowire logic devices on deformable nonplanar substrates. ACS Nano 5, 10009–10016 (2011).

Choi, M. S. et al. Promotional effects of ZnO-branching and Au-functionalization on the surface of SnO2 nanowires for NO2 sensing. J. Alloys Compd. 786, 27–39 (2019).

Yen, H., Seo, Y., Kaliaguine, S. & Kleitz, F. Role of metal–support interactions, particle size, and metal–metal synergy in CuNi nanocatalysts for H2 generation. ACS Catal. 5, 5505–5511 (2015).

Piotrowski, M. et al. Probing of thermal transport in 50 nm thick PbTe nanocrystal films by time-domain thermoreflectance. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 27127–27134 (2018).

Dong, J. et al. Facile synthesis of a nitrogen-doped graphene flower-like MnO2 nanocomposite and its application in supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 427, 986–993 (2018).

Kim, J.-H., Mirzaei, A., Kim, H. W. & Kim, S. S. Extremely sensitive and selective sub-ppm CO detection by the synergistic effect of Au nanoparticles and core-shell nanowires. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 248, 177–188 (2017).

Wu, W. et al. Non-centrosymmetric Au–SnO2 hybrid nanostructures with strong localization of plasmonic for enhanced photocatalysis application. Nanoscale 5, 5628–5636 (2013).

Bing, Y. et al. Multistep assembly of Au-loaded SnO2 hollow multilayered nanosheets for high-performance CO detection. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 227, 362–372 (2016).

Singh, N., Gupta, R. K. & Lee, P. S. Gold-nanoparticle-functionalized In2O3 nanowires as CO gas sensors with a significant enhancement in response. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3, 2246–2252 (2011).

Steinhauer, S. et al. Thermal oxidation of size-selected Pd nanoparticles supported on CuO nanowires: the role of the CuO–Pd interface. Chem. Mater. 29, 6153–6160 (2017).

Lai, X. et al. Ordered arrays of bead-chain-like In2O3 nanorods and their enhanced sensing performance for formaldehyde. Chem. Mater. 22, 3033–3042 (2010).

Kwon, Y. J. et al. Enhancement of the benzene-sensing performance of Si nanowires through the incorporation of TeO2 heterointerfaces and Pd-sensitization. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 239, 1085–1097 (2017).

Kim, J.-H., Mirzaei, A., Kim, H. W. & Kim, S. S. Combination of Pd loading and electron beam irradiation for superior hydrogen sensing of electrospun ZnO nanofibers. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 284, 628–637 (2019).

Pargar, F., Kolev, H., Koleva, D. A. & van Breugel, K. Microstructure, surface chemistry and electrochemical response of Ag|AgCl sensors in alkaline media. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 7527–7550 (2018).

Mehrer, H. Diffusion in solids. (Springer, 2007).

Lee, J. W. et al. Morphological modulation of urchin-like Zn2SnO4/SnO2 hollow spheres and their applications as photocatalysts and quartz crystal microbalance measurements. Appl. Surf. Sci. 474, 78–84 (2019).

Zuo, S. et al. SnO2/graphene oxide composite material with high rate performance applied in lithium storage capacity. Electrochim. Acta 264, 61–68 (2018).

Liu, Q., Xu, Y., Qiu, X., Huang, C. & Liu, M. Chemoselective hydrogenation of nitrobenzenes activated with tuned Au/h-BN. J. Catal. 370, 55–60 (2019).

Plodinec, M. et al. Black TiO2 nanotube arrays decorated with Ag nanoparticles for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic oxidation of salicylic acid. J. Alloys Compd. 776, 883–896 (2019).

Kim, N.-H. et al. Highly sensitive and selective acetone sensing performance of WO3 nanofibers functionalized by Rh2O3 nanoparticles. Sens. Actuator B-Chem. 224, 185–192 (2016).

Woo, H.-S., Na, C. W., Kim, I.-D. & Lee, J.-H. Highly sensitive and selective trimethylamine sensor using one-dimensional ZnO–Cr2O3 hetero-nanostructures. Nanotechnology 23, 245501 (2012).

Chen, X. H. & Moskovits, M. Observing catalysis through the agency of the participating electrons: Surface-chemistry-induced current changes in a tin oxide nanowire decorated with silver. Nano Lett. 7, 807–812 (2007).

Lee, S. et al. Effects of annealing temperature on the H2-sensing properties of Pd-decorated WO3 nanorods. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 124, 232 (2018).

Kwak, C.-H., Woo, H.-S. & Lee, J.-H. Selective trimethylamine sensors using Cr2O3-decorated SnO2 nanowires. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 204, 231–238 (2014).

Huang, S.-H. et al. Structures and catalytic properties of PtRu electrocatalysts prepared via the reduced RuO2 nanorods array. Langmuir 24, 2785–2791 (2008).

Sun, G.-J. et al. Synthesis of TiO2 nanorods decorated with NiO nanoparticles and their acetone sensing properties. Ceram. Int. 42, 1063–1069 (2016).

Rodríguez-Aguado, E. et al. Au nanoparticles supported on nanorod-like TiO2 as catalysts in the CO-PROX reaction under dark and light irradiation: Effect of acidic and alkaline synthesis conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44, 923–936 (2019).

Gan, X., Li, X., Gao, X., Zhuge, F. & Yu, W. ZnO nanowire/TiO2 nanoparticle photoanodes prepared by the ultrasonic irradiation assisted dip-coating method. Thin Solid Films 518, 4809–4812 (2010).

Kukkola, J. et al. Room temperature hydrogen sensors based on metal decorated WO3 nanowires. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 186, 90–95 (2013).

Lee, J.-S., Katoch, A., Kim, J.-H. & Kim, S. S. Effect of Au nanoparticle size on the gas-sensing performance of p-CuO nanowires. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 222, 307–314 (2016).

Trung, D. D. et al. Effective decoration of Pd nanoparticles on the surface of SnO2 nanowires for enhancement of CO gas -sensing performace. J. Hazard. Mater. 265, 124–132 (2014).

Formo, E., Lee, E., Campbell, D. & Xia, Y. Functionalization of electrospun TiO2 nanofibers with Pt nanoparticles and nanowires for catalytic applicaiton. Nano Lett. 8, 668–672 (2008).

Chang, S.-J., Hsueh, T.-J., Chen, I.-C. & Huang, B. R. Highly sensitive ZnO nanowire CO sensors with the adsorption of Au nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 19, 175502 (2008).

Chen, X. et al. NO2 sensing properties of one-pot-synthesized ZnO nanowires with Pd functionalization. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 280, 151–161 (2019).

Dong, W. et al. Room-temperature solution synthesis of Ag nanoparticles functionalized molybdenum oxide nanowires and their catalytic applications. Nanotechnology 23, 425602 (2012).

Jang, B.-H. et al. Selectivity enhancement of SnO2 nanofiber gas sensors by functionalization with Pt nanocatalysts and manipulation of the operation temperature. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 188, 156–168 (2013).

Chen, X. et al. Synthesis of ZnO nanowires/Au nanoparticles hybrid by a facile one-pot method and their enhanced NO2 sensing properties. J. Alloy. Compd. 783, 503–512 (2019).

Chávez, F. et al. Sensing performance of palladium-functionalized WO3 nanowires by a drop-casting method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 275, 28–35 (2013).

Shin, J., Choi, S.-J., Youn, D.-Y. & Kim, I.-D. Exhaled VOCs sensing properties of WO3 nanofibers functionalized by Pt and IrO2 nanoparticles for diagnosis of diabetes and halitosis. J. Electroceram. 29, 106–116 (2012).

Choi, S.-W., Katoch, A., Kim, J.-H. & Kim, S. S. Prominent reducing gas-sensing performances of n-SnO2 nanowires by local creation of p−n heterojunctions by functionalization with p-Cr2O3 nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 17723–17729 (2014).

Tak, Y., Hong, S. J., Lee, J. S. & Yong, K. Solution-based synthesis of a CdS nanoparticle/ZnO nanowire heterostructure array. Cryst. Growth Des. 9, 2627–2632 (2009).

Yin, H., Yu, K., Song, C., Huang, R. & Zhu, Z. Synthesis of Au-decorated V2O5@ZnO heteronanostructures and enhanced plasmonic photocatalytic activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 14851–14860 (2014).

Chen, T., Xing, G. Z., Zhang, Z., Chen, H. Y. & Wu, T. Tailoring the photoluminescence of ZnO nanowires using Au nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 19, 435711 (2008).

Shin, J. et al. Thin-wall assembled SnO2 fibers functionalized by catalytic Pt nanoparticles and their superior exhaled-breath-sensing properties for the diagnosis of diabetes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 2357–2367 (2013).

Li, L., Gu, L., Lou, Z., Fan, Z. & Shen, G. ZnO quantum dot decorated Zn2SnO4 nanowire heterojunction photodetectors with drastic performance enhancement and flexible ultraviolet image sensors. ACS Nano 11, 4067–4076 (2017).

Aluri, G. G. et al. Highly selective GaN-nanowire/TiO2-nanocluster hybrid sensors for detection of benzene and related environment pollutants. Nanotechnology 22, 295503 (2011).

Lu, M.-L., Lin, T.-Y., Weng, T.-M. & Chen, Y.-F. Large enhancement of photocurrent gain based on the composite of a single n-type SnO2 nanowire and p-type NiO nanoparticles. Opt. Express 19, 16772 (2011).

Pan, J. et al. SnO2@CdS nanowire-quantum dots heterostructures: tailoring optical properties of SnO2 for enhanced photodetection and photocatalysis. Nanoscale 5, 3022–3029 (2013).

Park, S. et al. Light-activated NO2 gas sensing of the networked CuO-decorated ZnS nanowire gas sensor. Appl. Phys. A 122, 504 (2016).

Peng, C., Wang, W., Zhang, W., Liang, Y. & Zhuo, L. Surface plasmon-driven photoelectrochemical water splitting of TiO2 nanowires decorated with Ag nanoparticles under visible light illuminaiton. Appl. Surf. Sci. 420, 286–295 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2017R1A6A3A11030900 and NRF-2019R1A6A1A11055660). We are grateful to Jiye Kim, Mun Young Koh, Baro Jin, Ha Jin Na, and Koh Eun Na for their cordiality and hospitality during the course of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.C., H.G.N. and S.K. developed the concept and H.W.K. and C.J. wrote the manuscript. M.S.C., H.G.N., J.H.B. and W.S.O. fabricated the samples and performed the measurements. S.-W.C., S.S.K. and K.H.L. provided theoretical basis. All authors contributed to interpretation of the fundamental theories, discussed the issues, and exchanged views on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, M.S., Na, H.G., Kim, S. et al. Synthesis of Au/SnO2 nanostructures allowing process variable control. Sci Rep 10, 346 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57222-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57222-z