Abstract

The self is built as an entity independent from the external world using the human ability to experience the senses of agency and ownership. Humans usually experience these senses during movement. Nevertheless, researchers recently reported that another person’s synchronous mirror-symmetrical movements elicited both agency and ownership in research participants. However, it is unclear whether this elicitation was caused by the synchronicity or the mirror symmetry of the movements. To address this question, we investigated the effect of interpersonal synchronization on the self-reported sense of agency and ownership in two conditions, using movements with and without mirror symmetry. Participants performed rhythmic hand movements while viewing the experimenter’s synchronous or random hand movements, and then reported their perceptions of agency and ownership in a questionnaire. We observed that agency and ownership were significantly elicited by the experimenter’s synchronous hand movements in both conditions. The results suggested that the synchronous movements of another person—rather than mirror- or non-mirror-symmetrical movements—appear to elicit the experience of a sense of agency and ownership. The results also suggested that people could experience these senses not only from their own movements but also from another person’s synchronous movements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When we move our arms in daily life, we certainly sense the execution of these movements in our bodies. People usually sense such experiences in their own movements, which provides what are known as the sense of agency and the sense of ownership1. These senses help us to avoid confusing our sensations with those of others (e.g. a cause-and-effect relationship in human behaviour) or feeling our own sensations in someone else’s body. For example, some patients suffering from asomatognosia feel that their own limbs are alien, despite tactile sensations in the ‘alien’ limb2. Hence, the ability to perceive self-agency and self-ownership is quite important for building the self as an entity that is independent of the external world. Surprisingly, sense of ownership was reported to be elicited in people viewing the synchronous brushing of a rubber hand while their own hands were hidden from view in the ‘rubber hand illusion’3. Furthermore, some researchers have found that the synchronous movements of a rubber hand, placed congruently with a participant’s hand, elicit a sense of agency and ownership in a participant4,5,6,7,8.

Interestingly, it has been reported that a sense of agency is elicited when the participant is synchronized with movements of a rubber hand rotated 180° with and without mirror symmetry, as if it was another person’s right or left hand6,7,8, whereas the sense of ownership was not elicited (Table 1). This research suggests that even though the rubber hand was in the position of another person, the participant had a sense of self-agency in relation to the rubber hand. On this topic, a recent study has indicated that people experienced both the senses of agency and ownership during interactions when viewing synchronous, mirror-symmetrical movements when seated face-to-face with an experimenter9, that is, another person’s movements that simultaneously included synchronous movements and mirror-symmetrical movements elicited senses of agency and ownership. However, there was no report of the effect of synchronous movements on the senses of agency and ownership in the non-mirror-symmetrical movement condition9. Thus, it is unclear whether synchronous movements or mirror-symmetrical movements elicited the senses of agency and ownership. Furthermore, it is suggested that synchronous movements may elicit these senses through temporal synchronous perceptions during interpersonal synchronization. That is, temporal synchronous perception could affect the multisensory integration of human perceptions, as the senses of agency10,11,12,13,14,15,16 and ownership13,17,18,19,20 were generated by multisensory integration. In contrast, if mirror-symmetrical movements elicit these senses, the visual information on mirrored movements during interpersonal synchronization could affect the multisensory integration of human perceptions to induce elicitation.

To address this question, we aimed to investigate the senses of agency and ownership in relation to another person’s mirror- and non-mirror-symmetrical movements. In particular, we conducted experiments to investigate perceptions of the senses of agency and ownership when the experimenter mimicked the movements of participants’ right or left hands in combinations of four conditions: mirrored, non-mirrored, synchronous movement, and random movement.

In the mirrored condition, the experimenter used his/her opposite hand to mimic the participant’s hand movements. In the non-mirrored condition, the experimenter used the same hand to mimic the participant’s hand movements. In addition, in the synchronous-movement condition, the experimenter performed the hand movements in synchronization with those of the participant. Furthermore, in the random movement condition, the experimenter performed the hand movements in synchronization with temporally random sounds. Here, although the asynchronous condition is an important control for the synchronous condition, other studies on the rubber hand illusion and the virtual hand illusion have shown that self-agency and self-ownership can be elicited by asynchronous movements4,21,22,23. Thus, a random condition would be a better control for the synchronous condition24. During the tasks, participants were always asked to look at the experimenter’s open-and-close hand movements. In this study, we used a 2 × 2 × 2 experimental design, with Synchrony (synchronous vs. random), Movement type (mirrored vs. non-mirrored), and Participant’s hand (left vs. right) as the independent variables, and we tracked the time-series data on the participant’s hand movements and the experimenter’s hand movements to check whether synchronization between their hand movements had been established.

Results

Comparability of all the synchronous conditions

To ensure the comparability of synchronous participant and experimenter movements in the mirrored and non-mirrored synchronous conditions, we monitored time-series data during the participant and experimenter movements. Then, we calculated the mean values of the intervals between participants’ and experimenters’ touches in all synchronous conditions and used a Friedman test to compare the differences between these mean values. The Friedman test indicated no differences between the synchronous conditions: χ2 (3, n = 32) = 4.3542, p = 0.23 (Fig. 1). This means that the participant and experimenter hand movements in all the mirrored and non-mirrored synchronous conditions were indeed synchronized; therefore, any differences in the agency and ownership ratings are not due to differences in hand movements in the synchronous conditions.

Agency ratings

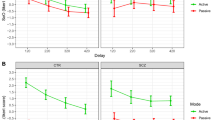

The median and percentile (25%; 75%) ratings for perceived sense of agency are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2. To examine the elicited sense of agency, we compared the agency statement with the corresponding control statement in synchronous conditions, and to the agency statement in the random conditions with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Then, we used a Bayesian Wilcoxon signed-rank test25 to measure the differences in the agency statement, including Q2, Q5, Q8, and Q11, between the mirrored and non-mirrored conditions. The Bayesian analysis used the Dirichlet process prior to testing the null hypothesis. Hypothesis H0 is that there is no significant difference between the agency statements in the mirrored and non-mirrored conditions.

Agency results for four questions in all of the conditions, showing the results of (a) Q2, (b) Q5, (c) Q8, and (d) Q11. The four experimental conditions are shown on the abscissa, and the ordinate shows the median scores in the question on the sense of agency. Bold lines indicate the median; upper and lower limits of the box plot indicate the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. Error bars represent the entire range of the ratings of the statement. R: right hand. L: left hand. P: the participant. E: the experimenter. Agency-S: agency statement in the synchronous-movement condition. Agency Control-S: agency control statement in the synchronous-movement condition. Agency-Ra: agency statement in the random movement condition. N.S.: no significant difference. *p < 0.001.

Q226,27,28, Q58,28, and Q1126,29 concern the sense of agency in the rubber hand illusion. Q2 is ‘The experimenter’s hand moved just like I wanted it to, as if it was obeying my will’. Q5 is ‘I felt as if I was causing the movement that I saw’. Q11 is ‘I felt as if I was controlling the movements of the experimenter’s hand’. The median ratings of these questions were positive in synchronous conditions (Table 2, Fig. 2a–c), indicating a subjective perception of the sense of agency. They were significantly higher than the medians of the corresponding control statements in the synchronous conditions, and the agency statements in the random conditions (all p < 0.0001; Table 3). Q8 is ‘Whenever I moved my finger, I expected the experimenter’s finger to move in the same way’26,30,31. The medians of Q8 ratings in synchronous conditions were positive (Table 2 and Fig. 2d). They were significantly higher than the corresponding control statement in the synchronous conditions (p < 0.001; Table 3), and higher than the agency statement in the random conditions (Table 3). Hence, the questionnaire data clearly show that participants experienced a strong sense of agency over the experimenter’s hand in all of the synchronous conditions that was not evident in the random conditions.

To compare the overall statements of agency between mirrored and non-mirrored conditions, we used the mean value of the question responses in the agency statement. Hereafter, P and E mean ‘participant’ and ‘experimenter’, respectively.

After Bayesian analysis, the Bayes factors of the P(H0|Data) were 0.471 (Right(P)–Left(E) vs. Right(P)–Right(E)), 0.472 (Right(P)–Left(E) vs. Left(P)–Left(E)), 0.246 (Left(P)– Right(E) vs. Right(P)–Right(E)), and 0.257 (Left(P)–Right(E) vs. Right(P)–Right(E)). According to a suggestion from Jeffreys32, there is anecdotal evidence of similarity between the mirrored condition of Right(P)–Left(E) and non-mirrored conditions of Right(P)–Right(E) and Left(P)–Left(E), and there is moderate evidence of similarity between the mirrored condition of Left(P)–Right(E) and non-mirrored conditions of Right(P)–Right(E) and Left(P)–Left(E). Therefore, this result supports the null hypothesis H0, at least as a tendency. That is, the results showing no significant difference indicated that synchronous rather than visual information from mirrored movements elicit a sense of agency during interpersonal synchronization.

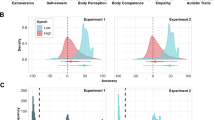

Ownership ratings

The median and percentile (25%; 75%) of a perceived sense of ownership ratings are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 3. To examine the elicited sense of ownership, we compared the ownership statements with the corresponding control statements in the synchronous conditions and with the corresponding ratings in the random conditions with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Table 5 and Fig. 3). Then, we used a Bayesian Wilcoxon signed-ranks test25 to measure the differences in the ownership statements, including Q1, Q3, Q6, and Q9, between the mirrored and non-mirrored conditions. The Bayesian analysis used a Dirichlet process prior as a further test of the null results. The null hypothesis, H0, is that there is no significant difference in the ownership statement between mirrored and non-mirrored conditions.

Ownership results for four questions in all of the conditions, showing the results of (a) Q1, (b) Q3, (c) Q6, and (d) Q9. The four experimental conditions are shown on the abscissa, and the ordinate shows the median scores in the question on the sense of ownership. Bold lines indicate the median; upper and lower limits of the box plot indicate the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. Error bars represent the whole range of the ratings of the statement. R: right hand. L: left hand. P: the participant. E: the experimenter. Ownership-S: ownership statement in the synchronous-movement condition. Ownership Control-S: ownership control statement in the synchronous-movement condition. Ownership-Ra: ownership statement in the random movement condition. N.S.: no significant difference. *p < 0.001.

Q1 and Q6 are ‘I felt as if I was looking at my own hand’ and ‘I felt as if the experimenter’s hand was my hand’. These questions are more directly related to an illusory feeling of ownership3,33,34. The medians of Q1 and three medians of Q6 in the synchronous conditions were positive (Table 4, Fig. 3a,c); only the median of Q6 in Right(P)–Right(E) was equal to 0, indicating a subjective perception of the sense of ownership21. The median scores of Q1 and three medians of Q6 in the synchronous conditions were also significantly higher than the medians for the corresponding control statements in synchronous conditions and the ownership ratings in the random conditions (all p < 0.001; Table 5). The questionnaire data clearly indicated that participants in the mirrored and non-mirrored movement conditions perceived a significant sense of ownership when the movement was synchronous (all p < 0.001; Table 5), but not when it was temporally random.

Q3 is ‘It seems as if I was sensing the movement of my finger in the location where the experimenter’s finger moved’, which concerns a sense of location33,34. The medians of Right(P)–Left(E), Left(P)–Right(E), and Right(P)–Right(E) were significantly higher than those of the corresponding control statements in the synchronous conditions and the ownership statements in the random conditions (all p < 0.001; Table 5 and Fig. 3b). The median score of Left(P)–Left(E) was higher than that of the corresponding control statements (p = 0.025) and significantly higher than that of the ownership statement in the random conditions (p < 0.001), although the median was −1.00.

Q9 is ‘I felt as if the experimenter’s hand was part of my body’, which differs from ‘I felt as if the rubber hand was part of my hand’ in the rubber hand illusion4,5. The medians of Q9 in Left(P)–Right(E) were significantly higher than those of the corresponding control statements in the synchronous conditions (p = 0.002) and the ownership statement in the random conditions (p = 0.001). The medians of Right(P)–Left(E), Right(P)–Right(E), and Left(P)–Left(E) were significantly higher than the corresponding ratings in the random conditions (p ≤ 0.001; Table 5 and Fig. 3d), and higher than those of the corresponding control statements (p = 0.069, 0.0199, and 0.207).

To compare the overall statements regarding sense of ownership of mirrored and non-mirrored conditions, except for Q9, we used the mean value of responses to the ownership questions. Q9 was excluded because of its improper design, as described below. After Bayesian analysis, the Bayes factors of the P(H0|Data) for mirrored and non-mirrored conditions were 0.196 (Right(P)–Left(E) vs. Right(P)–Right(E)), 0.424 (Right(P)–Left(E) vs. Left(P)–Left(E)), 0.147 (Left(P)–Right(E) vs. Right(P)–Right(E)), and 0.352 (Left(P)–Right(E) vs. Right(P)–Right(E)). According to Jeffreys32, there is anecdotal evidence of similarity between the non-mirrored condition of Left(P)–Left(E) and the mirrored condition of Right(P)–Left(E) and Left(P)–Right(E) and moderate evidence of similarity between the non-mirrored condition of Right(P)–Right(E) and mirrored conditions of Right(P)–Left(E) and Left(P)–Right(E). Therefore, this result supports the null hypothesis H0, at least as a tendency. That is, the lack of a significant difference indicates that synchronous movements, rather than the mirrored movements of visual information, would elicit a sense of ownership during interpersonal synchronization.

Correlation between agency and ownership

In addition, to analyse whether the senses of agency and ownership scores were correlated in all the synchronous conditions, we ran a correlation analysis in which we calculated the mean value of the agency and ownership statements, A Spearman’s rho test was used to test significance because of the non-parametric data4,5. The result showed close correlations between the agency and ownership statements in all synchronous conditions: (Right(P)–Left(E) condition, r = 0.294, n = 32, p = 0.05; Left(P)–Right(E) condition, r = 0.547, n = 32, p = 0.0005; Right(P)–Right(E) condition, r = 0.418, n = 32, p = 0.009; and Left(P)–Left(E) condition, r = 0.583, n = 32, p = 0.002).

Discussion

The present study investigated whether the elicitation of agency and ownership during interpersonal synchronization is caused by the synchronous movements or mirror-symmetrical movements of another person. The absence of significant time-series differences indicated that the agency and ownership ratings in all the synchronous conditions, including the mirrored and non-mirrored conditions, were comparable. According to the questionnaire results, participants seemed to experience agency and ownership during interpersonal synchronization in both the mirrored and non-mirrored conditions. This indicates that interpersonal synchronization—including mirrored and non-mirrored movements—elicits the senses of agency and ownership. These results answer the remaining question of whether another person’s synchronous movements—rather than mirrored movements—are crucial for participants to experience these senses.

As measured by Q2 and Q11 in the present study, agency was related to feelings of being able to move the rubber hand and control it35,36. The positive median of Q2 and Q11 responses and their significant differences from those of the control statements and random statements showed elicitation of a sense of agency. Furthermore, the results of Q5 (relating to the sense of causing the viewed movement) also indicated that participants perceived a sense of agency. The positive median of Q8 scores and the significant differences from the control statements were consistent with those of Q2, Q5, and Q11, although the median was higher than, but not significantly different from, those of responses to the random statements. This may be expected even in random conditions because people synchronize their movements as soon as they exchange sensory information;37,38 it is easier to move synchronously together, and it also ‘makes us feel good about ourselves’39,40.

Furthermore, the lack of significant differences in responses to the agency statement between mirrored and non-mirrored conditions indicates that synchronous movements, rather than mirror-symmetrical movements, elicit a sense of agency. That is, the temporal synchronous perception during interpersonal synchronization could affect multisensory integration to induce this elicitation. Moreover, such processing would be related to the temporal integration window on which temporal synchronous perceptions depend. Some studies investigated the temporal integration window during the elicitation of agency and they found that a delay between an action and its feedback can generate the sense of agency41,42. The temporal integration window of perceived agency is even recalibrated along with perceived sensorimotor simultaneity during recalibrated training11,12,14,15,43, and sense of agency can in turn influence temporal recalibration44,45. However, some limitations should be noted, and these need to be resolved in our future work. According to the Bayesian analysis, the value of P(H0|Data) provides moderate support for the null hypothesis, H0, of similarity of responses in the mirrored condition of Left(P)–Right(E) and non-mirrored conditions of Right(P)–Right(E) and Left(P)–Left(E), whereas the value of P(H0|Data) only shows a tendency towards similarity between the mirrored condition of Right(P)–Left(E) and non-mirrored conditions of Right(P)–Right(E) and Left(P)–Left(E).

The elicitation of agency is consistent with that reported in previous work, including the study of person–person interactions by Zhou et al.9 and studies of human–rubber hand interactions6,7,8 (Table 1). In the human–rubber hand interactions, researchers have found that the synchronous movements of a rubber hand, placed congruently with a participant’s hand, elicited a sense of agency in the participant4,5,6,7,8, and that a sense of agency was elicited when the participant was interacting but viewing the synchronous movements of a 180° rotated rubber hand in mirror-and non-mirror-symmetrical ways, as if it was another person’s right or left hand6,7,8 (Table 1).

The consistency of the results from all of these studies suggests that a sense of agency is related to the temporal synchrony of movements between partners in an interaction (whether person–person or human–rubber), but not to mirrored movements per se. It is well known that a sense of agency is elicited when one is the agent of one’s own actions. Some studies have reported that the congruence of self-generated movements and perceptions of feedback from the temporal synchrony of movements play a role in eliciting a sense of agency27,46. In the synchronous conditions of the present study, participants observed a match between the hand movements they performed and those of the experimenter. The temporal synchrony in such interactions may imply a connection between the participant’s intention to move and the perceived movements of the experimenter47, and perhaps this connection elicits a sense of agency.

The questions on the sense of ownership (Q1 and Q6 in the present study) are usually used to measure the ownership illusion. The positive median of responses to these questions and their significant difference from those of the control and random statements indicated the elicitation of a sense of ownership. The medians of Q3 were slightly higher than or equal to 0 in the mirrored conditions. These medians indicate that participants might have been uncertain whether their hand was in the same position as that of the experimenter. This is because 0 means ‘uncertain’ on the seven-point Likert scale (−3 = totally disagree, 0 = uncertain, +3 = totally agree). This kind of uncertainty seemed consistent with participants’ sense of hand location in Zhou et al.9, in which the median of the shifted hand position (i.e., 3.32) was slightly below the uncertain level (i.e., 4).

In the present study, the medians of Q9 were almost all negative and did not differ significantly from those of the control statements or random statements. This might have been caused by the improper design of Q9 itself. Participants did not respond as expected to Q9 and Q6 because Q9 reminded them to consider where their hand was. In addition, the rubber hand and virtual hand48, which do not belong to anyone, are difficult to think of as part of someone’s body, while another person’s hand might easily be considered a part of someone’s body. Therefore, we suggest that the questionnaire results indicate that participants experienced a sense of ownership.

Furthermore, the lack of significant difference in the ownership statements between the mirrored and non-mirrored conditions indicates that human synchronous movements, rather than human mirror-symmetrical movements, would elicit a sense of ownership. As for similar results in the elicitation of agency in the present study, we also suggest that such processing is related to the temporal integration window on which temporal synchronous perception depends. Some previous studies have reported that the senses of agency and ownership are temporally plastic49,50,51,52. However, some limitations should be noted that need to be resolved in our future work. According to the Bayesian analysis, the value of P(H0|Data) provides moderate support for the null hypothesis, H0, for the non-mirrored condition of Right(P)–Right(E) and mirrored conditions of Right(P)–Left(E) and Left(P)–Right(E), whereas the value of P(H0|Data) only shows a tendency in the non-mirrored condition of Left(P)–Left(E) and mirrored conditions of Right(P)–Left(E) and Left(P)–Right(E). Finally, no studies to date have investigated the relationship between the time delay in interpersonal synchronization and the elicitation of the senses of agency and ownership.

The result of sense of ownership is consistent with the human–human results of Zhou et al.9 but inconsistent with those of research on human–rubber hand interactions6,7,8 (Table 1). In the human–rubber hand interactions, researchers have found that the synchronous movements of a rubber hand, placed congruently with a participant’s hand, elicited a sense of ownership in the participant4,5,6,7,8, but not when the participant was interacting while viewing the mirror- and non-mirror-symmetrical synchronous movements of a 180° rotated rubber hand6,7,8 (Table 1). Thus, the experience of ownership found in the present study and by Zhou et al.9 as well as the lack of ownership experienced in human–rubber hand studies6,7,8 indicate that the temporal synchrony of movements is insufficient to explain the elicitation of ownership. Thus, synchronization with a human regardless of the mirrored and non-mirrored movements plays some role in the sense of ownership, but synchronization with a rubber hand does not. This suggests that a sense of ownership may play a role in human social functions rather than simply referring to the feeling that ‘my body belongs to me’52. Based on work with the rubber hand illusion and the virtual hand illusion, a sense of ownership may involve quite plastic, top-down processing when either the rubber hand or virtual hand is placed in a realistic position in relation to the observer/participant30. We speculate that a sense of ownership is part of the processing that occurs in social interactions and in the flexible top-down processing in face-to-face interactions. Such top-down processing may have caused the mean ratings for ownership to be lower than those for agency in the present study because participants used face-to-face interaction with the experimenter as well as the experimenter’s hand movements to make their final decisions of the feeling of ownership. In addition, it is necessary to discover the mechanism underlying the elicitation of the sense of ownership in interpersonal interactions. This mechanism remains unclear because it was not elicited when the participant was interacting while viewing the mirror- and non-mirror-symmetrical synchronous movements of a 180° rotated rubber hand6,7,8 (Table 1).

The correlation results show a close correlation between the agency and ownership statements in all synchronous conditions. The close correlation is consistent with the results of some recent studies53,54,55, which have suggested that the senses of agency and ownership could partly overlap at the neurofunctional level and have even proposed an ‘interactive’ model for the two senses, as the sense of ownership per se can act on the sense of agency attribution55.

In the present study, we investigated whether it is the human synchronous movements or human mirrored movements that made participants feel both a sense of agency and ownership. We compared the senses of agency and ownership in the mirrored synchronous and random conditions and in the non-mirrored synchronous and random conditions. To ensure comparability across the synchronous conditions, we established the consistency of synchronous hand movements between the participant and experimenter by tracking their hand movements. The results from the agency and ownership analyses indicated that it was synchronous movements regardless of mirroring that elicited senses of agency and ownership. Hence, the results also suggest that people could experience these senses not only from their own movements but also from others’ synchronous movements.

Methods

Participants

Computation of the sample size was performed with G-Power 3 (Heinrich Heine University—Institut für experimentelle psychologie; www.psycho.uni- duesseldorf.de/abteilungen/aap/gpower3). With respect to the perception of sense of ownership during interpersonal synchronization, we based our sample size estimation on a previous study9. As indicated by Zhou et al., the effect of interpersonal synchronization on the elicitation of sense of ownership has a Cohens’ d = 1.18 with a mean of 4.00 and standard deviation of 1.81 (modified for within-subject design). Assuming an anticipated effect size equal to 1.18, an α error probability of 0.05 and a power (1 – β error probability) of 0.95, the resulting total sample size is n = 12. Thus, based on this power analysis, we conservatively estimated a larger sample size and recruited 32 participants for the study. These 32 participants (15 females, 17 males; mean age: 23.9 years; range: 22–30 years) completed the experiment and were compensated for their participation. All participants were right-handed23 and none exhibited any difficulty moving their hands or fingers. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no history of neurological disease. They were naive as to the experiment’s purpose. We obtained written informed consent from each participant prior to participation. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tokyo Institute of Technology and the methods were conducted in accordance with its approved guidelines.

Design

This experiment assessed whether Synchrony and Movement type (mirrored vs. non-mirrored) influence the senses of agency and ownership during interpersonal synchronization. Synchrony between a participant’s and an experimenter’s hand movements was manipulated so that movements were either temporally congruent (i.e., the experimenter synchronously imitated the participant’s hand movement) or incongruent (i.e., temporally random). We manipulated movement type by seating the participant and experimenter opposite each other and having the experimenter move either the opposite (mirrored condition) or the same (non-mirrored condition) hand as the participant. We also had the participants move either their left and right hands; thus, the experiment had a 2 Synchrony (synchronous vs. random) × 2 Movement type (mirrored vs. non-mirrored) × 2 Participant’s hand (left vs. right) design. A fully factorial combination of these three factors produced eight conditions (Table 6). Participants followed these within-subject conditions in a random order.

Apparatus and procedure

The experiment was conducted in a quiet experimental room at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. The participant sat comfortably at a table and put his/her hand into a wooden box with the dimensions 21 cm (h) × 40 cm (w) × 60 cm (d) (Fig. 4a). The box was placed on a table directly in front of the participant, in alignment with the sagittal body midline. Each participant was paired with an experimenter of the same sex, who sat on the opposite side of the rectangular table (75 cm × 120 cm) (Fig. 4a). The distance between the participant’s and experimenter’s fingertips was around 50 cm. We used a Count Down Digital Timer (TD-394; Tanita Co., Tokyo, Japan) and sensors (FSR402; Interlink Electronics Co., Camarillo, CA, USA) to track inverse changes in resistance in response to increases/decreases in applied force in relation to the time-series data during synchronous movements of the participant and experimenter.

Prior to the experiment, each participant was asked to read instructions on the procedure. The participant’s task was to open and close his or her hand (Fig. 4b,c) at approximately 1 s intervals. The participants received brief training in how to perform the appropriate open-and-close motion and how to use the digital timer for pacing. The timer counted down from 1 to zero minutes during training, but it was not used during experimental trials. During the experiment, sensors were used to track the timing of the participant’s and experimenter’s open-and-close hand movements, and the participant was asked to look at the experimenter’s hand movements. The order of conditions was counterbalanced among participants. The participants had a 2–3-minute break after each condition to prevent the previous experimental condition from influencing the next one. The experiment took approximately 90 minutes to complete.

In the synchronous mirrored condition, the participant was asked to perform the open-and-close motion with his/her right or left hand at approximately 1 s intervals for 60 s, and stare at the experimenter’s hand motions while keeping his/her own rhythm. The experimenter sat opposite the participant and synchronously moved his/her opposite hand in imitation of the participant’s hand movements. White noise helped the participant to focus on the hand movement task. On completion of the experiment, participants completed the 12-item questionnaire (Table 7).

In the random mirrored condition, the experimenter performed the hand movements in synchronization with temporally random sounds rather than in synchronization with the participant’s hand movements. Intervals between these sounds were randomly set between 0.9 and 1.5 s because participants’ intervals were approximately 1 s. The other procedures for this condition were the same as in the synchronous mirrored condition.

In the synchronous non-mirrored condition, the participants performed the open-and-close motion with their right or left hand, and the experimenter synchronously performed the motion with the same hand (right or left). The other procedures were the same as in the synchronous mirrored condition.

In the random non-mirrored condition, the experimenter performed the hand movements in synchronization with temporally random sounds rather than with the participant’s hand movements. The other procedures were the same as in the synchronous non-mirrored condition.

Measures of agency and ownership

To assess the subjective experiences of agency and ownership, we used a 12-item questionnaire adopted from Braun et al.30, and Kalckert and Ehrsson4 and used in traditional rubber hand illusion experiments3,56 (Table 7). The questions were presented in a pseudo-randomized order and rated on a seven-point Likert scale (−3 = totally disagree, 0 = uncertain, +3 = totally agree). A Likert scale (printed on A4 paper) accompanying the verbal presentation of each statement was used to facilitate responses when necessary. The responses to four items were used to obtain a single value for the perceived senses of agency and ownership. The remaining four items were control statements, with two for agency and two for ownership30. Hence, if a sense of agency is induced, participants should give high scores on the sense of agency questions highly in the four synchronous conditions and lower scores for the agency control questions, as responses to these questions should not specifically be affected by the manipulation of agency. Similarly, high ownership questions and low or negative ownership control questions mean that a sense of ownership is induced.

Data analysis

Prior to conducting data analyses, we used the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05) to see whether the data were normally distributed. Because several datasets failed to meet the criteria for normal distribution, we used appropriate non-parametric tests. We used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for pairwise comparisons. All tests were two-tailed, and all analyses were conducted using the R software package (R Studio 1.1.419, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

We calculated time-series data for each participant’s and experimenter’s synchronous and random hand movements to ensure there was no difference between their movements in synchronous conditions. Then, we calculated participants’ perceived senses of agency and ownership during synchronous movements with the experimenter, as follows. First, we compared agency and ownership scores with their respective control statements for each experimental condition to see whether there was a significant sense of agency or ownership in each synchronous condition. Second, we compared agency and ownership scores from synchronous conditions with those from random conditions to test for significant differences between synchronous and random conditions. Third, we examined whether the experimenter’s mirrored movements were needed to elicit a sense of agency or ownership during interpersonal synchronization, by using a Bayesian version of the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test25. Finally, we measured the correlation of the agency and ownership statements in all the synchronous conditions by a Spearman rho test because of the non-parametric data4,5.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gallagher, I. I. Philosophical conceptions of the self: implications for cognitive science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4, 14–21 (2000).

de Vignemont, F. Habeas corpus: the sense of ownership of one’s own body. Mind and Language 22, 427–449 (2007).

Botvinick, M. & Cohen, J. Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature 391, 756 (1998).

Kalckert, A. & Ehrsson, H. H. Moving a rubber hand that feels like your own: a dissociation of ownership and agency. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, 40 (2012).

Kalckert, A. & Ehrsson, H. H. The moving rubber hand illusion revisited: comparing movements and visuotactile stimulation to induce illusory ownership. Conscious. Cogn. 26, 117–132 (2014).

Jenkinson, P. M. & Preston, C. New reflections on agency and body ownership: the moving rubber hand illusion in the mirror. Conscious. Cogn. 33, 432–442 (2015).

Karabanov, A. N., Ritterband-Rosenbaum, A., Christensen, M. S., Siebner, H. R. & Nielsen, J. B. Modulation of fronto-parietal connections during the rubber hand illusion. Eur. J. Neurosci. 45, 964–974 (2017).

Marotta, A. et al. The moving rubber hand illusion reveals that explicit sense of agency for tapping movements is preserved in functional movement disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 291 (2017).

Zhou, A., Zhang, Y., Yin, Y. & Yang, Y. The mirrored hand illusion: I control, so I possess? Perception 44, 1225–1230 (2015).

Kawabe, T., Roseboom, W. & Nishida, S. The sense of agency is action–effect causality perception based on cross-modal grouping. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 280 (2013).

Corveleyn, X., López-Moliner, J. & Coello, Y. Sensorimotor adaptation modifies action effects on sensory binding. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 77, 626–637 (2015).

Timm, J., Schönwiesner, M., SanMiguel, I. & Schröger, E. Sensation of agency and perception of temporal order. Conscious Cogn. 23, 42–52 (2014).

Imaizumi, S. & Asai, T. Dissociation of agency and body ownership following visuomotor temporal recalibration. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 9, 1–10 (2015).

Haering, C. & Kiesel, A. Was it me when it happened too early? Experience of delayed effects shapes sense of agency. Cognition 136, 38–42 (2015).

Haering, C. & Kiesel, A. Time perception and the experience of agency. Psychol. Res. 80, 286–297 (2016).

Rohde, M. & Ernst, M. O. Time, agency, and sensory feedback delays during action. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 8, 193–199 (2016).

Ehrsson, H. H. The concept of body ownership and its relationship to multisensory integration. The new handbook of multisensory processes (ed. Stein, B. E.). 775–793 (Cambridge, 2012).

Maselli, A., Kilteni, K., López-Moliner, J. & Maselli, M. S. The sense of body ownership relaxes temporal constraints for multisensory integration. Scientific Reports 6, 30628 (2016).

Costantini, M. et al. Temporal limits on rubber hand illusion reflect individuals’ temporal resolution in multisensory perception. Cognition 157, 39–48 (2016).

Lane, T., Yeh, S. L., Tseng, P. & Chang, A. Y. Timing disownership experiences in the rubber hand illusion. Cognitive research: principles and implications 2, 4 (2017).

Martini, M., Perez-Marcos, D. & Sanchez-Vives, M. V. What color is my arm? Changes in skin color of an embodied virtual arm modulates pain threshold. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 438 (2013).

Rognini, G. et al. Visuo-tactile integration and body ownership during self-generated action. Eur. J. Neurosci. 37, 1120–1129 (2013).

Osimo, S. A., Pizarro, R., Spanlang, B. & Slater, M. Conversations between self and self as Sigmund Freud—a virtual body ownership paradigm for self counselling. Sci. Rep. 5, 13899 (2015).

Wen, W. et al. Goal-directed movement enhances body representation updating. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 329 (2016).

Benavoli, A., Mangili, F., Corani, G., Zaffalon, M. & Ruggeri, F. A Bayesian Wilcoxon signed-rank test based on the Dirichlet process. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2014) 1–9 (2014).

Caspar, E. A., Cleeremans, A. & Haggard, P. The relationship between human agency and embodiment. Conscious. Cogn. 33, 226–236 (2015).

Argelaguet, F., Hoyet, L., Trico, M. & Lecuyer, A. The role of interaction in virtual embodiment: effects of the virtual hand representation. 2016 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR) 3–10, https://doi.org/10.1109/VR.2016.7504682 (2016).

Salomon, R. et al. Changing motor perception by sensorimotor conflicts and body ownership. Sci. Rep. 6, 25847 (2016).

Kilteni, K., Normand, J. M., Sanchez-Vives, M. V. & Slater, M. Extending body space in immersive virtual reality: a very long arm illusion. PLoS ONE 7, e40867 (2012).

Braun, N., Thorne, J. D., Hildebrandt, H. & Debener, S. Interplay of agency and ownership: the intentional binding and rubber hand illusion paradigm combined. PLoS One 9, e111967 (2014).

Caspar, E. A. et al. New frontiers in the rubber hand experiment: when a robotic hand becomes one’s own. Behav. Res. 47, 744–755 (2014).

Jeffreys, H. Theory of probability (3rd ed.). (Oxford, 1961).

Ocklenburg, S., Rüther, N., Peterburs, J., Pinnow, M. & Güntürkün, O. Laterality in the rubber hand illusion. Laterality 16, 174–187 (2011).

Marotta, A., Tinazzi, M., Cavedini, C., Zampini, M. & Fiorio, M. Individual differences in the rubber hand illusion are related to sensory suggestibility. PLoS One 11, e0168489 (2016).

Germine, L., Benson, T. L., Cohen, F. & Hooker, C. L. Psychosis-proneness and the rubber hand illusion of body ownership. Psychiatry Res. 207, 45–52 (2013).

Longo, M. R., Schüür, F., Kammers, M. P. M., Tsakiris, M. & Haggard, P. What is embodiment? A psychometric approach. Cognition 107, 978–998 (2008).

Issartel, J., Marin, L. & Cadopi, M. Unintended interpersonal co-ordination: can we march to the beat of our own drum? Neurosci. Lett. 411, 174–179 (2007).

Lorenz, T., Vlaskamp, B. N. S., Kasparbauer, A. M., Mörtl, A. & Hirche, S. Dyadic movement synchronization while performing incongruent trajectories requires mutual adaptation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 461 (2014).

McNeill, W. H. Keeping together in time (Harvard University Press, 1995).

Lumsden, J., Miles, L. K. & Macrae, C. N. Sync or sink? Interpersonal synchrony impacts self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 5, 1064 (2014).

Asai, T. & Tanno, Y. Prediction and consequence of self-oriented action and sense of self-agency. Jpn. J. Pers. 16, 56–65 (2007).

Farrer, C., Valentin, G. & Hupéet, J. M. The time windows of the sense of agency. Consciousness and Cognition 22, 1431–1441 (2013).

Cunningham, D. W., Chatziastros, A., von der Heyde, M. & Bülthoff, H. H. Driving in the future: Temporal visuomotor adaptation and generalization. Journal of Vision 1, 88–98 (2001).

Rohde, M., van Dam, L. C. J. & Ernst, M. O. Predictability is necessary for closed-loop visual feedback delay adaptation. Journal of Vision 14, 1–23 (2014).

Yarrow, K., Sverdrup-Stueland, I., Roseboom, W. & Arnold, D. H. Sensorimotor temporal recalibration within and across limbs. J. Exp. Psycho. Hum. Percept. Perform. 39, 1678–1689 (2013).

Ratcliffe, N. & Newport, R. The effect of visual, spatial and temporal manipulations on embodiment and action. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 227 (2017).

Abdulkarim, Z. & Ehrsson, H. H. No causal link between changes in hand position sense and feeling of limb ownership in the rubber hand illusion. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 78, 707–720 (2015).

Hoyet, L., Argelaguet, F., Nicole, C. & Lécuyer, A. ‘Wow! I have six fingers!’: would you accept structural changes of your hand in VR? Front. Robot. AI 3, 27 (2016).

Blakemore, S. J., Wolpert, D. M. & Frith, C. D. Abnormalities in the awareness of action. Trends Cogn. Sci. 6, 237–242 (2002).

Bays, P. M., Wolpert, D. M. & Flanagan, J. R. Perception of the consequences of self-action is temporally tuned and event driven. Curr. Biol. 15, 1125–1128 (2005).

Makin, T. R., Holmes, N. P. & Ehrsson, H. H. On the other hand: dummy hands and peripersonal space. Behav. Brain. Res. 191, 1–10 (2008).

Tsakiris, M. My body in the brain: a neurocognitive model of body-ownership. Neuropsychologia 48, 703–712 (2010).

Kilteni, K., Groten, R. & Slater, M. The sense of embodiment in virtual reality. Presence Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 21, 373–387 (2015).

Seghezzi, S., Giannini, G. & Zapparoli, L. Neurofunctional correlates of body-ownership and sense of agency: A meta-analytical account of self-consciousness. Cortex 121, 169–178 (2019).

Pyasik, M., Furlanetto, T. & Pia, L. The role of body-related afferent signals in human sense of agency. Journal of Experimental Neuroscience 13, 1–4 (2019).

Kontaris, I. & Downing, P. E. Reflections on the hand: the use of a mirror highlights the contributions of interpreted and retinotopic representations in the rubber-hand illusion. Perception 40, 1320–1334 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yufeng Mao and Liang Shan of Tokyo Institute of Technology for their help as experimenters and their assistance with programming. The present study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI), Research Activity start-up Grant Number 17H06673.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.H. designed and performed the experiment, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. H.O. co-designed and wrote the manuscript. K.O. co-designed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. S.A. co-performed the experiment and co-analysed the data. Y.M. co-designed the experiment and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, Q., Ora, H., Ogawa, Ki. et al. Effects of Human Synchronous Hand Movements in Eliciting a Sense of Agency and Ownership. Sci Rep 10, 2038 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59014-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59014-2

This article is cited by

-

Investigating the impact of motion visual synchrony on self face recognition using real time morphing

Scientific Reports (2024)