Abstract

Epilepsy is a network disease. The primary somatosensory cortex (S1) is usually considered to be intact, but could be subclinically disturbed based on abnormal functional connectivity in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). We aimed to investigate if the S1 of TLE is abnormally modulated. Somatosensory evoked magnetic fields (SEFs) evoked by median nerve stimulation were recorded in each hemisphere of 15 TLE patients and 28 normal subjects. All responses were separately averaged in the awake state and light sleep using background magnetoencephalography. Latency and strength of the equivalent current dipole (ECD) was compared between the groups for the first (M1) and second peaks. Latencies showed no significant differences between the groups in either wakefulness or light sleep. ECD strengths were significantly lower in TLE patients than in controls only during wakefulness. The reduction of M1 ECD strength in the awake state is significantly correlated with duration of epilepsy. SEFs of TLE patients showed pure ECD strength reduction without latency delay. The phenomenon occurred exclusively during wakefulness, suggesting that a wakefulness-specific modulator of S1 is abnormal in TLE. Repetitive seizures may gradually insult the modulator of S1 distant from the epileptogenic network.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epilepsy is a disease characterized by disturbance of the excitatory-inhibitory synaptic balance in the epileptogenic network (EN)1,2. Abnormal neuronal imbalance occurs in the temporal and connected regions in temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE)3. The primary auditory area and auditory association areas may be included in the EN of patients with TLE4. Consequently, the auditory-evoked response is useful for evaluating cortical activities in functional areas. Recent studies using auditory-evoked magnetic fields reported physiological changes in auditory function in patients with mesial TLE5,6,7. The functional connectivity of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) may also be disturbed inside the EN in patients with TLE. Recent functional magnetic resonance (MR) imaging studies revealed that activity of the ARAS was negatively correlated with increased frequency of focal impaired awareness seizures8, and/or neurocognitive problems8,9. The ARAS pathway is crucial in maintaining arousal and consciousness10,11,12. The ARAS widely projects to the cerebral cortex including the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) from the reticular formation in the brainstem13, and modulates cortical function through the balance between excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmissions mainly in the awake state10,14,15.

The S1 is usually considered to be outside the EN in patients with TLE. The primary somatosensory function is believed to be normal in TLE, but could be subclinically disturbed based on the abnormal functional connectivity described above. The N20m response (M1 in the present study) to median nerve stimulation, the first cortical somatosensory evoked field (SEF) peak and its counterpart somatosensory evoked potential (SEP) N20, is an established marker of primary somatosensory function16,17. The N20m/N20 is a tangential current to the scalp generated at the posterior bank of the central sulcus, so the equivalent current dipole (ECD) of N20m is suitable for quantitative evaluation because magnetoencephalography (MEG) is exclusively sensitive to cortical tangential activity16,17,18. Amplitude enlargement of N20m during sleep may occur in healthy subjects19,20, but remains unevaluated in patients with neurological disease.

The present study evaluated median nerve SEFs in the awake state and light sleep of patients with TLE to clarify whether the excitation level is abnormal in the S1 distant from the EN.

Results

Figure 1 shows typical examples of SEF waveforms during awake state and light sleep in a patient with TLE and two normal subjects. The amplitudes of M1 and M2 were smaller in TLE patients than in normal subjects in the awake state but not in light sleep.

Typical examples of somatosensory evoked field (SEF) waveforms in temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients and normal subjects. Stacked waveforms of selected magnetoencephalography channels showing the SEFs over the contralateral hemisphere induced by median nerve stimulation at the wrist. Every single evoked response was separately averaged for the awake state (stage W) and light sleep (stage N1–N2). Note smaller amplitudes of first (M1) and second (M2) peaks of SEF in TLE patients than in normal subjects in the awake state but not in light sleep.

Comparison of latency between TLE patients and normal subjects

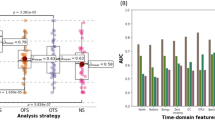

No significant differences were found in latency of the M1 and M2 peaks of SEFs between TLE patients and normal subjects, during both the awake state and light sleep (Fig. 2).

Comparison of somatosensory evoked field (SEF) latency between temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients and normal subjects. Latency normalized by height at the first (M1) and second (M2) peaks of SEFs induced by median nerve stimulation was compared between TLE patients and normal subjects, during both the awake state (stage W) and light sleep (stage N1–N2). Box-and-whisker plots show minimum, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and maximum values from the bottom to the top. No significant differences were found in latency at the M1 and M2 of SEFs between TLE patients and normal subjects, during both the awake state and light sleep.

Comparison of ECD strength between TLE patients and normal subjects

ECD strengths at the M1 and M2 were significantly lower in TLE patients than in normal subjects during the awake state (P = 0.028 and P < 0.001, respectively, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test), but not during light sleep (Fig. 3).

Comparison of somatosensory evoked field (SEF) strength between temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients and normal subjects. Equivalent current dipole (ECD) strength at the first (M1) and second (M2) peaks of SEFs induced by median nerve stimulation was compared between TLE patients and normal subjects, during both the awake state (stage W) and light sleep (stage N1–N2). Box-and-whisker plots show the minimum, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and maximum values from the bottom to the top. ECD strengths at the M1 and M2 were significantly lower in TLE patients than normal subjects during the awake state (P = 0.03 and P < 0.001, respectively, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test), but not during light sleep.

Correlation between M1 ECD strength in the awake state and variables

The correlations between M1 ECD strength in the awake state and clinical variables are summarized in Table 1. No significant correlations were found between M1 ECD strength and age, sex, side of TLE, presence of lesion, presence of hippocampal sclerosis (HS), and relationship to epileptic focus. Lower M1 ECD strength in the awake state was significantly correlated with duration of epilepsy in TLE patients (Spearman’s ρ = − 0.483., P = 0.012) (Fig. 4). M1 strength of the approximate line at seizure onset (0 year) was almost equal to the average for normal subjects.

Correlation between strength in the awake state and duration of epilepsy in temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients. Reduction of equivalent current dipole (ECD) strength at the first peak (M1) of somatosensory evoked fields in the awake state was correlated with duration of epilepsy in TLE patients. Note the M1 strength of the approximate line at seizure onset (0 year) was almost equal to the average of normal subjects.

Discussion

The present study revealed that the ECD strength of SEFs was significantly lower in patients with TLE than in normal subjects exclusively during the awake state without prolongation of latency. Moreover, the lower M1 ECD strength in the awake state was correlated with duration of epilepsy. These results imply that cortical function even outside the EN is abnormal in TLE patients as a function of epilepsy duration.

First, no significant differences were found in SEF latencies between the TLE and control groups. SEP and SEF latencies are prolonged if nerve conduction is affected at any level of the somatosensory pathway from the peripheral nerves, spinal cord, and brainstem to the cortex21,22,23. Therefore, the absence of abnormality in the nerve conduction pathway to the S1 was confirmed. Nevertheless, lower SEF ECD strength was detected in only the TLE patients exclusively during the awake state. Some awake state-specific modulators must be abnormal at the S1 in TLE to cause such reduction of M1 and M2 ECD strengths during the awake state but not during light sleep.

The ARAS may be involved in at least some of the present findings of SEF abnormalities during awake state, because the ARAS is more active in the awake state than during sleep14,24. Therefore, disturbance of the ARAS may have resulted in the suppression of primary SEF magnitude in our TLE patients during the awake state. Previous investigations of SEP25 and SEF19 revealed decreased high frequency oscillations in the S1 during sleep, suggesting decreased function of the inhibitory neurons.

Pure amplitude reduction without latency delay of N20/N20m is an extremely rare phenomenon, reported only in a few cases of direct cortical damage such as in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease26. Amplitude reduction of N20/N20m is usually associated with latency delay as occurs in multiple sclerosis23, brain lesions, and severe head injury21,22. Greatly increased SEP and SEF, often named “giant SEP and SEF,” are frequently reported in epilepsy with cortical myoclonus27,28,29,30 and traumas21. However, amplitude enlargement occurs only in the later components such as M2, but not in N20m (M1) or N20. The present results are quite unique because M1 (N20m) showed “pure amplitude reduction without latency delay,” representing pure dysfunction at the level of the S1.

One important finding of the present study is the new fact that M1 ECD magnitude in the awake state is inversely correlated with duration of epilepsy. Deterioration of an awake state-specific modulator of the S1, such as ARAS, may start at the clinical onset of TLE, because the M1 magnitude of the approximate line at seizure onset (0 year) is almost equal to the average for normal subjects. A previous functional MR imaging study revealed that ARAS connectivity was significantly lower in patients with TLE than in controls, particularly in those with neocortical regions8. The diminished ARAS connectivity was related to increased frequency of focal impaired awareness seizures, which are associated with impairments in verbal intelligence quotient, attention, executive function, language, and visuospatial memory on neuropsychological evaluation8. Therefore, repetitive seizures in TLE, but not preceding pathology, are likely to gradually insult an awake state-specific modulator of the S1 distant from the EN.

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may modify SEF, due to the effect on the synaptic neurotransmission and the modification of cortical excitability. Recent studies reported no significant differences31,32,33 or prolonged latency34 in SEP during treatment with AEDs. Therefore, AEDs are not considered to cause significant change in the amplitude of SEP.

Previously, separation of the awake and sleep recordings for SEP or SEF analysis was conducted in only normal subjects20,35,36,37. Our present method involving strict separation of the awake and sleep stages by visual assessment of background MEG could also be used to evaluate cortical excitation in the somatosensory areas distant from the EN in other types of epilepsy. Moreover, this novel method will be useful for further studies to evaluate cortical excitation in various types of neurological diseases.

The present study has the limitation of small sample size of SEF data during light sleep. MEG recordings with the head inside the helmet during repetitive electrical stimulation may have prevented some subjects falling asleep. Further studies including more data during light sleep are needed to confirm our results.

Materials and methods

Participants

The present study included 15 patients with TLE (8 males; age 20–29 years, mean 25.0 years) who underwent comprehensive evaluation for epilepsy at Tohoku University Hospital Epilepsy Monitoring Unit, Sendai, Japan from January 2015 to December 2017, as well as 28 healthy volunteers (19 males; age 20–27 years, mean 22.4 years). The patients were electro-clinically diagnosed with TLE based on the clinical history and the results of long-term video EEG monitoring. Patients with multi-lobar epilepsy, such as frontal or parietal lobe epilepsy combined with TLE, were excluded. None of the TLE patients had structural abnormalities in the primary somatosensory cortex, as verified by MR imaging. The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2.

The study was approved by the ethical committee of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (2010-189, 2012-1-459, 2017-2-102-1) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or legally authorized representatives and subjects in accordance with the requirements of the ethical committee. All parts of the present study were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (1991).

MEG recordings with median nerve stimulation

MEG was performed with a 200-channel whole-head MEG system with axial gradiometers (RICOH Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in a magnetically shielded room. The detailed conditions of the MEG system used in this study have already been described38,39. Briefly, the sensors were first-order axial gradiometers with a baseline of 50 mm and 15.5-mm diameter coils. The sensors were arranged in a uniform array over a helmet-shaped surface at the bottom of a Dewar vessel. The centers of two adjacent coils were separated by a mean distance of 25 mm.

All patients and subjects lay in the supine position, with the head location determined by the positions of five fiduciary markers consisting of induction coils placed at known locations on the scalp. The head shape and coil positions were established using a three-dimensional digitizer (FastSCAN Cobra, Polhemus, Inc., Colchester, VT) based on three-dimensional MR images obtained for all patients and subjects using a 3T MR system (Achieva, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands; or Magnetom Trio, Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany)38,39.

The left and right median nerves at the wrist were stimulated independently by constant-current stimuli of biphasic square-wave impulses with 0.3 ms duration at 0.7 Hz21,40. Stimulus intensity was set at 1.5 times the motor threshold to evoke a twitch of the thumb21. The conditions for data acquisition with the MEG systems were sampling at 1000 or 2000 Hz and low-pass filtering at 100, 200, or 500 Hz in each patient or subject.

Analysis of SEFs in the awake state and light sleep

Sleep stages were scored in every 20-s epoch of MEG recording by a well-trained technologist (MI) based on the following criteria. Stage W (awake state) was determined when posterior dominant alpha rhythm accounted for 50% or more of the recording with blinking or muscle artifacts. Stage N1–N2 (light sleep) was determined when posterior dominant alpha rhythm accounted for less than 50% of the recording without blinking or muscle artifacts, or when the recording included vertex sharp transients, spindles, or K-complexes. Stage N3 (slow wave sleep) was not recorded in this study because no patients or subjects showed high-amplitude slow waves in the recordings. Stage REM (rapid eye movement sleep) was not recorded in this study because no patients or subjects showed REM artifacts in the recordings.

SEFs were separately averaged for awake state and light sleep from 30 hemispheres of 15 patients with TLE and 56 hemispheres of 28 healthy volunteers. Consequently, SEF data in awake state were compared between 28 hemispheres of the TLE group (15 of 15 patients) and 47 hemispheres of the control group (25 of 28 subjects). SEF data in light sleep were compared between 19 hemispheres of the TLE group (11 of 15 patients) and 11 hemispheres of the control group (7 of 28 subjects). The data from 20 ms before to 100 ms after the stimulus onset were averaged for 100–300 times. SEF data were included for evaluation if more than 100 averages were available for each awake-sleep stage for each hemisphere. Latency corrected for subject height [ms/m] and ECD strength41 was evaluated for the first peak (M1, N20m) and second peak (M2)18.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Two group comparison of SEFs was performed with the two-sided Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical significance was assumed for P < 0.05. The correlation between M1 ECD strength in the awake state and clinical variables including age, sex, side of TLE, presence of lesion, presence of HS, relationship to epileptic focus, and duration of epilepsy were also evaluated. The two-sided Mann–Whitney U test was used for categorical variables. Spearman’s ρ correlation coefficient test (2-tailed, α = 0.05) was used to analyze the correlation between M1 ECD strength and continuous variables. Outlier values defined as outside the mean ± 2 standard deviations were excluded from further analysis.

Data availability

Dr. Ishida had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

Bradford, H. F. Glutamate, GABA and epilepsy. Prog. Neurobiol. 47, 477–511 (1995).

Olsen, R. W. & Avoli, M. GABA and epileptogenesis. Epilepsia 38, 399–407 (1997).

Karunakaran, S. et al. The interictal mesial temporal lobe epilepsy network. Epilepsia 59, 244–258 (2018).

Mehta, A. D. et al. Seizure propagation in a patient with musicogenic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 14, 421–424 (2009).

Chatani, H. et al. Neuromagnetic evidence for hippocampal moduration of auditory processing. Neuroimage 124, 256–266 (2016).

Matsubara, T. et al. Altered neural synchronization to pure tone stimulation in patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: An MEG study. Epilepsy Behav. 88, 96–105 (2018).

Matsubara, T. et al. Monaural 40-Hz auditory steady-state magnetic responses can be useful for identifying epileptic focus in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 130, 341–351 (2019).

Englot, D. J. et al. Functional connectivity disturbances of the ascending reticular activating system in temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 88, 925–932 (2017).

Englot, D. J. et al. Relating structural and functional brainstem connectivity to disease measures in epilepsy. Neurology 91, e67–e77 (2018).

Schiff, N. D. Central thalamic contributions to arousal regulation and neurological disorders of consciousness. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1129, 105–118 (2008).

Parvizi, J. & Damasio, A. Consciousness and the brainstem. Cognition 79, 135–160 (2001).

Zeman, A. Consciousness. Brain 124, 1263–1289 (2001).

Jang, S. & Kwak, S. The upper ascending reticular activating system between intralaminar thalamic nuclei and cerebral cortex in the human brain. J. Kor. Phys. Ther. 29, 109–114. https://doi.org/10.18857/jkpt.2017.29.3.109 (2017).

Hobson, J. A. & Pace-Schott, E. F. The cognitive neuroscience of sleep: Neuronal systems, consciousness and learning. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 679–693 (2002).

Fuentealba, P. & Steriade, M. The reticular nucleus revisited: Intrinsic and network properties of a thalamic pacemaker. Prog. Neurobiol. 75, 125–141 (2005).

Baumgartner, C. et al. Neuromagnetic investigation of somatotopy of human hand somatosensory cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 87, 641–648 (1991).

Hari, R. & Forss, N. Magnetoencephalography in the study of human somatosensory cortical processing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 354, 1145–1154 (1999).

Kawamura, T. et al. Neuromagnetic evidence of pre- and post-central cortical sources of somatosensory evoked responses. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 100, 44–50 (1996).

Hashimoto, I., Mashiko, T. & Imada, T. Somatic evoked high-frequency magnetic oscillations reflect activity of inhibitory interneurons in the human somatosensory cortex. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 100, 189–203 (1996).

Kitamura, Y., Kakigi, R., Hoshiyama, M., Koyama, S. & Nakamura, A. Effects of sleep on somatosensory evoked responses in human: A magnetoencephalographic study. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 4, 275–279 (1996).

Iwasaki, M. et al. Somatosensory evoked fields in comatose survivors after severe traumatic brain injury. Clin. Neurophysiol. 112, 205–211 (2001).

Mazzini, L. et al. Somatosensory and motor evoked potentials at different stages of recovery from severe traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 80, 33–39 (1999).

Karhu, J., Hari, R., Mäkelä, J. P., Huttunen, J. & Knuutila, J. Cortical somatosensory magnetic responses in multiple sclerosis. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 83, 192–200 (1992).

Steriade, M. The corticothalamic system in sleep. Front. Biosci. 8, d878–d899 (2003).

Halboni, P. et al. Sleep stage dependant changes of the high-frequency part of the somatosensory evoked potentials at the thalamus and cortex. Clin. Neurophysiol. 111, 2277–2284 (2000).

Shiga, Y., Seki, H., Onuma, A., Shimizu, H. & Itoyama, Y. Decrement of N20 amplitude of the median nerve somatosensory evoked potential in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease patients. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 18, 576–582 (2001).

Shibasaki, H., Yamashita, Y., Neshige, R., Tobimatsu, S. & Fukui, R. Pathogenesis of giant somatosensory evoked potentials in progressive myoclonic epilepsy. Brain 108, 225–240 (1985).

Uesaka, Y., Ugawa, Y., Yumoto, M., Sakuta, M. & Kanazawa, I. Giant somatosensory evoked magnetic field in patients with myoclonus epilepsy. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 87, 300–305 (1993).

Hitomi, T. et al. Increased cortical hyperexcitability and exaggerated myoclonus with aging in benign adult familial myoclonus epilepsy. Mov. Disord. 26, 1509–1514 (2011).

Salas-Puig, J., Tuñon, A., Diaz, M. & Lahoz, C. H. Somatosensory evoked potentials in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia 33, 527–530 (1992).

Sendrowski, K., Sobaniec, W., Boćkowski, L., Kułak, W. & Smigielska-Kuzia, J. Somatosensory evoked potentials in epileptic children treated with carbamazepine or valproate in monotherapy—A preliminary study. Adv. Med. Sci. 55, 212–215 (2010).

Borah, N. C. & Matheshwari, M. C. Effect of antiepileptic drugs on short-latency somatosensory evoked potentials. Acta Neurol. Scand. 71, 331–333 (1985).

Carenini, L., Bottacchi, E., Camerlingo, M., D’Alessandro, G. & Mamoli, A. Carbamazepine does not affect short-latency somatosensory evoked potentials: A longitudinal study in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Epilepsia 29, 145–148 (1988).

Mervaala, E., Keränen, T., Tiihonen, P. & Riekkinen, P. The effects of carbamazepine and sodium valproate on SEPs and BAEPs. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 68, 475–478 (1987).

Noguchi, Y. et al. Dissociated changes of frontal and parietal somatosensory evoked potentials in sleep. Neurology 45, 154–160 (1995).

Yamada, T. et al. Changes of short latency somatosensory evoked potential in sleep. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 70, 126–136 (1988).

Nakano, S., Tsuji, S., Matsunaga, K. & Murai, Y. Effect of sleep stage on somatosensory evoked potentials by median nerve stimulation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 96, 385–389 (1995).

Usubuchi, H. et al. Effects of contralateral noise on the 20-Hz auditory steady state response-magnetoencephalography study. PLoS ONE 9, e99457. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099457 (2014).

Kawase, T. et al. Impact of audio-visual asynchrony on lip-reading effects—Neuromagnetic and psychophysical study. PLoS ONE 11, e0168740. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168740 (2016).

Nagamatsu, K. et al. Neuromagnetic localization of N15, the initial cortical response to lip stimulus. NeuroReport 12, 1–5 (2001).

Sarvas, J. Basic mathematical and electromagnetic concepts of the biomagnetic inverse problem. Phys. Med. Biol. 32, 11–22 (1987).

Acknowledgements

Supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. JP16H05435 and No. JP16K09708), and Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants on rare and intractable diseases from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (H26-nanchitou-ippan-051, H29-nanchitou-ippan-010). We wish to thank Dr. Takuhiro Yamaguchi (Division of Biostatistics, Department of Public Health and Forensic Medicine, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine) for his comments on the statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.I., K.J. and N.N. conceived of the study. M.I., K.J., Y.K., A.K. and N.N. collected, analyzed, or interpreted data. M.I., K.J., R.K. and N.N. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. K.J. and N.N. supervised the entire process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Ishida reports no disclosures. Dr. Jin has received speaker’s fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo, UCB Japan, and Eisai Co., Ltd. Dr. Kakisaka reports no disclosures. Dr. Kanno is Associate Professor of the Donated Fund Laboratory from RICOH Japan Corp. Dr. Kawashima reports no disclosures. Dr. Nakasato is Chair of the Collaborative Laboratory with RICOH Japan Corp. and has received research funds and speaker’s fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Daiichi-Sankyo, UCB Japan, Fukuda Denshi, Pfizer Japan, and Eisai Co., Ltd.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishida, M., Jin, K., Kakisaka, Y. et al. Awake state-specific suppression of primary somatosensory evoked response correlated with duration of temporal lobe epilepsy. Sci Rep 10, 15895 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73051-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73051-x

This article is cited by

-

Scalp attached tangential magnetoencephalography using tunnel magneto-resistive sensors

Scientific Reports (2022)