Abstract

Activated coke (AC) has great potential in the field of low-temperature NO removal (DeNOx), especially the branch prepared by blending modification. In this study, the AC-based pyrolusite and/or titanium ore blended catalysts were prepared and applied for DeNOx. The results show blending pyrolusite and titanium ore promoted the catalytic performance of AC (Px@AC, Tix@AC) clearly, and the co-blending of two of them showed a synergistic effect. The (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC performed the highest NO conversion of 66.4%, improved 16.9% and 16.0% respectively compared with P15@AC and Ti15@AC. For the (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC DeNOx, its relative better porous structure (SBET = 364 m2/g, Vmic = 0.156 cm3/g) makes better mass transfer and more active sites exposure, stronger surface acidity (C–O, 19.43%; C=O, 4.16%) is more favorable to the NH3 adsorption, and Ti, Mn and Fe formed bridge structure fasted the lactic oxygen recovery and electron transfer. The DeNOx of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC followed both the E–R and L–H mechanism, both the gaseous and adsorbed NO reacted with the activated NH3 due to the active sites provided by both the carbon and titanium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen oxide (NOx) is an important atmospheric contaminant that contributes substantially to fine particulate matter production and contributes to climate change due to its secondary transformation to nitrate1 and/or nitrous oxide (N2O, an important greenhouse gas)2. To reduce NOx emission, therefore, is imperative for a sustainable environment and clean skies. Selective catalytic reduction (SCR) is currently the most efficient method and widely used flue gas NOx removal technology3,4, and the key to it is the catalyst. After decades of devotion, a variety of catalysts based on different application requirements have been developed in laboratory5,6,7. Whereas only the V2O5–WO3(MoO3)/TiO2 series catalysts, which typically works in a high-temperature range (300–400 °C), is widely industrialized5. The middle- and low-temperature range NOx removal in the non-ferrous metallurgy, construction materials, and coking industry et al. is still a long way to go.

Carbonaceous materials, such as activated carbon8,9, carbon nanotube10, biochar/biocarbon11, et al. have been attracting considerable interest in the field of air pollution control. The use of activated coke (AC)-based catalyst, in particular, has good potential for industrial application due to its relatively low cost and excellent adaptability12. To improve the reaction activity, integration of AC with transition metals has been studied13,14, and some of them observed good NH3-SCR performance14,15,16. However, most of the AC-based catalysts were prepared by the impregnation method, and this method can use only soluble transition metal salts with a relatively low decomposition temperature as precursor12,17. The catalyst preparation is complicated and high-cost, which restrain its wide application.

To simplify the preparation and reduce costs, the blending method that integrates AC preparation and catalyzation modification in one step extend the applicability of the catalyst precursor to catch great attention in the past few years. Jiang had prepared the metal oxide-blended activated carbon from walnut shells for flue gas desulfurization18, as well as the coal-based AC13,19, and the recent work observed clear improvement of SCR activity of the blending-modified AC20. However, studies on the SCR application of the blending-modified AC is still in its infancy. Therefore, studying NOx removal using the new blending-modified AC is important in integrating low-temperature flue gas desulfurization and denitrification.

Pyrolusite and titanium ore are low-cost natural minerals and mainly contain the Mn, Fe, Ti, and other trace metal elements. Previous work reported that Fe2O3 exhibits a synergistic effect with MnO2 to enhance the low-temperature NOx removal activity of catalyst21. Yang et al. found that the N2O formation of Mn-based SCR catalyst can be effectively inhibited using the Ti–Fe structure carrier22. If pyrolusite and titanium ore can be used to co-blending modification of AC to prepare a highly efficient low-temperature SCR catalyst, then the preparation cost can be significantly reduced and better industrialization prospects can be ensured.

In this study, the natural pyrolusite from South Africa and titanium ore from Sichuan, China, were used to prepare the blending-modified AC for low-temperature NOx removal. Based on the characterization of porosity and surface chemistry, the denitrification performance of AC modified by single pyrolusite or titanium ore, their mixture, and the interactions of the two ores were discussed. Besides, the NOx removal mechanism over the composite catalyst was proposed based on the transient response analysis coupled with the variation study of surface chemistry.

Materials and experiments

Materials

Bituminous coal and 1/3 coking coal from Shanxi Province, China, were used as carbon sources to prepare the new blending-modified AC catalyst. Elemental analysis (EA 3000, Elemental, Italy) showed that bituminous coal consisted of (wt%) C = 73.78, H = 9.69, N = 2.29, S = 1.76, and O = 14.10, the 1/3 coking coal consisted of (wt%) C = 74.23, H = 4.83, N = 2.08, S = 0.47, and O = 17.39. The binder used was coal tar from Sichuan Coal and Coking Group Co., Ltd. and contained (wt. %) C = 80.08, N = 1.20, H = 3.91, S = 0.75, and O = 14.06. The pyrolusite from South Africa and titanium ore from Panzhihua (China) were used as precursors to prepare the AC catalyst. Table 1 lists the ingredient analysis based on X-ray fluorescence (XRF-1800, Shimadzu, JP).

Preparation of ACs

The bituminous coal and 1/3 coking coal mixture at a 7:3 weight ratio was used as the carbon source of AC, and the blending modification method that integrates the preparation and modification in one step was used. Coal powder was passed through a 200-mesh screen and mixed homogeneously in a kneading machine (10 min). Approximately 10.0 wt% of water and 42.0 wt% of coal tar were then successively introduced through continuous agitation. When the mixture showed a metallic luster for approximately 30 min, it was transferred to a hydraulic machine barrel and extruded at 10 MPa pressure to obtain a 3 mm diameter columnar semi-coke. The only difference in pyrolusite and titanium ore-blended AC preparation was that the calculated content of pyrolusite and/or titanium ore (also passed through a 200-mesh screen) was added directly to the coal mixture and stirred for at least 15 min before the water and coal tar were added.

After an overnight drying process, the semi-coke was activated, followed by continuous carbonization–activation process. The whole activation process involves pre-oxidation, carbonization, and steam activation at 270, 600, and 900 °C for 60, 40, and 60 min, respectively. The air was used for pre-oxidation, water was introduced during the activation at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/g·h to form steam, and other moments were run in N2. The tube furnace was cooled naturally at room temperature in nitrogen. The pyrolusite- and titanium-blended ACs are presented as Px@AC and Tix@AC, respectively, and the combination of the two-ore co-modified ACs is referred to as (P/Ti-a/b)x@AC. P represents pyrolusite, Ti corresponds to the titanium ore, a/b is the combined weight ratio of P and Ti, and x is the total loaded weight percentage of the carbon source.

Characterizations

The pore structure and surface area were characterized using ASAP 2460 (Micromeritics, USA) at − 196 °C after 8 h degas at 250 °C. The nitrogen adsorbed at 0.995 relative pressure was used to calculate the total pore volume. The surface area was calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller model. The micropore volume was calculated using the t-plot model, and the mesopore distribution was obtained using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda method. X-ray diffraction analysis was performed using an X-Pert Pro MPD diffractometer (Panalytical Co., Ltd., NLD) with Cu Kα radiation (30 V and 20 A) from 10° to 80°. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was obtained by a Nicolet 6700 infrared spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) in the range of 4000–400 cm−1. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterization was performed by a PHI 5000 XPS measurements (ESCA Microprobe, JP) using a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV).

Denitrification performance test

The NH3-SCR of ACs was conducted in a lab-scale fixed-bed evaluation system. The total flow rate of the simulated flue gas was 500 mL/min, which contained 500 ppm NO and 500 ppm NH3, 5.0% O2, and balanced with N2. The corresponding space velocity and reaction temperature were 1000 h−1 and 150 °C, respectively. The inlet and outlet NO concentrations were continuously monitored using an online flue gas analyzer (Gasboard-3000, China). Given the adsorption property of AC, NH3 was replaced with N2 in the initial stage until the outlet number of NO was almost the same as that of the inlet. After NH3 was introduced to the simulated gas, the denitrification test began. The NO removal performance of AC was expressed by the NO conversion and calculated based on Eq. 1, where η is NO conversion (%), and Cin and Cout are the inlet and outlet NO concentrations (ppm), respectively.

Results and discussion

Catalytic performance of AC

The NH3-SCR performance of the prepared three different AC-based catalysts is showing in Fig. 1. The NO conversion of virgin AC was only approximately 20.4%, and all the blending-modified ACs showed clear improvement. As is shown in Fig. 1a, blending 5.0 wt% of pyrolusite increased the NO removal efficiency of P5@AC to 40.5%, it was twice that of virgin AC. As the blending content gradually increased, the SCR performance of Px@AC first increased and then relatively decreased. P15@AC showed the highest NO conversion at 49.5%. Beyond this addition, the decrease in NO conversion may be attributed to the pore blockage because greater ash and metal content were easily agglomerated under high-temperature conditions23. The NO removal activity of Tix@AC showed a similar variation as Px@AC, as shown in Fig. 1b. The best NH3-SCR performance of approximately 50.5% at a 15.0 wt% blending ratio, slightly higher than that of P15@AC. The improvement of the denitrification performance indicates the suitability of pyrolusite and titanium ore as precursors to prepare the AC-based SCR catalyst. The SCR performance of Px@AC in this study was relatively lower than that reported in previous work20, this could be attributed to the different pyrolusite precursors used, which had a different proportion of ingredients; we advance this point in this study. The preparation process also had some differences, which affected the activity of AC through surface chemistry variation, such as the functional groups and metal active sites. Additional details of this issue are still being determined.

Figure 2 shows the co-blended (P/Ti-a/b)x@AC to investigate the interaction between the two different minerals. Figure 2a shows the NO removal performance of (P/Ti-1/1)x@AC at a different total dosage of pyrolusite and titanium ore. The (P/Ti-1/1)x@ACs are performing a better denitrification activity than AC, Px@AC, and Tix@AC. When the total dosage was 5.0 wt%, the co-blended sample at the pyrolusite/titanium ore proportion ((P/Ti-1/1)5@ACs) of 1/1 achieved comparable activity to the P15@AC and Ti15@AC. The catalytic performance of (P/Ti-1/1)x@AC gradually strengthened as the blending amount gradually increased, and the (P/Ti-1/1)15@AC showed the best performance at 1/1 mixing ratio, with the NO removal efficiency increasing to 60.5%. Kept the blending ratio at 15.0 wt% constant, the influence of blending proportions of pyrolusite and titanium ore was also investigated, and their NH3-SCR performance is shown in Fig. 2b. The denitrification performance of co-blended (P/Ti-a/b)15@AC improved when the pyrolusite/titanium ore proportion changed from 1/5 to 1/2, the highest NO conversion of 66.4% was obtained when the pyrolusite/titanium ore proportion (a/b) was 1/2 ((P/Ti-1/2)15@AC). Increasing pyrolusite content, the activity of (P/Ti-a/b)15@AC first showed a reasonable decrease and remained relatively stable in the range of 61.2%–62.3% until the a/b was 3/1. Compared with the Px@AC and Tix@AC, the improved NO removal of (P/Ti-a/b)x@AC (a/b < = 3/1) indicates that a synergistic reaction occurred between the metal oxides in the two minerals, and the optimum proportion of the two minerals was 1/2, which corresponded to the best catalytic performance. The N2 selectivity test of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC shows only ~ 25 ± 3 ppm of N2O detected in the outlet flue gas, corresponding to ~ 91.8% of N2 selectivity.

Characterization of AC

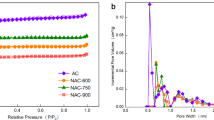

Porosity of the AC

Textual properties of the (P/Ti-a/b)x@AC samples were characterized using N2 adsorption, and the results are listed in Table 2. The (P/Ti-a/b)x@AC samples were still typically microporous material, their Vmic/Vtot are higher than 70.0%. The porosity of the (P/Ti-1/1)x@AC are worse than the virgin AC. The increased loading content showed a limited effect on the SBET when the blending amount within 15.0 wt%, varying in the range from 330 to 348 m2/g. The low SBET can be attributed to the greater ash content after the introduction of the mineral, and the metal oxides can also strengthen the agglomeration process during the carbonization–activation process24,25. Keep the total blending content of the two ores constant (15.0 wt%), the SBET and pore volume were similar to the characteristic of “mountain” with the increased proportion of pyrolusite. The (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC had the best textual properties of 364 m2/g of SBET and 0.192 cm3/g of Vtot. SBET increased as the pyrolusite increased from 1/5 to 1/2, thus indicating that pyrolusite could certainly improve the pore structure of AC during water steam activation. This result is consistent with the previous study24. Figure 2a shows the catalytic performance of (P/Ti-1/1)x@AC strengthened gradually when the blending ratio changed from 5.0 wt% to 15.0 wt%. This finding indicates that the textural properties of the catalysts were not the pacing factor to determine the catalytic activity, and the surface metal oxides and functional groups could be the principal in determining NO removal26. The SBET and pore volume of the (P/Ti-a/b)15@AC sample further confirmed this point. As the pyrolusite/titanium ore ratio (a/b) varied from 1/5 to 1/2, the SBET and pore volume of (P/Ti-a/b)15@AC increased after the NH3-SCR performance improved. As the pyrolusite percentage increased, especially when the a/b was in the range from 2/3 to 2/1, the (P/Ti-a/b)15@AC showed relatively poor activity (Fig. 2b) despite its comparable porosity (Table 2).

Surface functional groups

FTIR analysis was applied to analyze the surface functional groups of the AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC. As is shown in Fig. 3, both samples show almost similar FTIR spectra, differences showed in their intensities and slightly shift suggesting very limited changes of the surface chemistry25. For both the AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC, their spectra assigned the absorption band to the O–H stretching vibration (approximately 3400 cm−1)27, CH2 and CH3 (1460 cm−1)28, COOH (approximately 1090 cm−1), and C–H (at 875 cm−1)29, respectively. Be differently, AC showed adsorption band at 1640–1630 cm−1, which belongs to the moisture peaks overlapped with C=C and C=O stretching in phenylpropanoid side chains, and aromatic skeleton vibration30. The disappearance of the 1640–1630 cm−1 band on (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC could be due to the bridging interactions of the blended micro metal oxide particles to the surface of AC31. The intensity of COOH was enhanced by the pyrolusite and titanium ore co-blending, indicating a stronger surface acidity of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC, coupling with the loss of C=O located at 1640–1630 cm−1, the surface NH3 adsorption could be fasted to improve the SCR performance of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC.

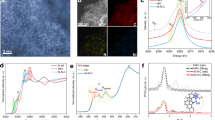

The XPS characterization was applied to gain insight into the nature of surface functional groups. The full XPS spectrum of AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC is shown in Fig. 4a,b, and the surface composition is based on it listed in Table 3. The (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC had high surface oxygen content, it was 17.11%, 4.58% higher than AC (12.53%), which indicates the participation of blended metal oxides during steam activation helps the AC reserve surface oxygen components. Table 4 shows the functional group distribution based on the C 1s high deconvolution spectrum. The C–C of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC is 4.42% less than that of virgin AC. Additional oxygen functional groups were observed, and the relative contents of C–O, C=O, and π–π* increased by 3.32%, 0.78%, and 0.40% compared with the virgin AC when (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC was treated with strong surface acidity8. The O 1s deconvolution spectra are showing in Fig. 4c, d. Both AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC have three energy peaks. They were Peak I (assigned at 530.4–531.0 eV) belongs to C=O groups in esters, carbonyl, and quinone, Peak II (centered at 532.4–533.1 eV) corresponds to C–OH and/or C–O–C groups in esters, amides, and others, and Peak III (located at 533.6–535.6 eV) corresponds to chemisorbed oxygen and/or water. Given the blended metal oxides, (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC had another peak centered at 529.2–530.3 eV, which was mainly attributed to the lattice oxygen32. The increased lattice oxygen of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC is consistent with its improved NO removal performance and plays an important role in promoting the formation of nitrate species by participating in the NO oxidation, thus further hastening the NH3-SCR33. Thus, the chemical properties of AC, such as oxygen functional groups and lattice oxygen, were more important factors than the physical properties, which is consistent with the previous results34. The consensus is that the oxygen vacancy and lattice could facilitate the oxidation of NO to NO2 and further accelerate the ‘fast SCR’ process35.

Metallic chemistry characterization

Figure 5 shows the XRD patterns of the AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC before and after NO removal. For the AC sample, only one clear SiO2 peak at 2θ = 26.71° was detected without considering the carbon base. For the (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC, the SiO2 peak was weakened, and the peaks located at 32.48°, 35.25°, 48.70°, 53.10°, and 61.54° matched well with FeTiO3 (JCPD 29-0733). The MnFeO4 at 2θ = 34.98° (JCPD 29-0733) and Fe2O3 at 2θ = 35.42° (JCPD 99-0073) were also detected, but they were covered or bonded to the FeTiO3 peak at 35.25°. Besides, there was a peak ascribed to SiC at 2θ = 59.1° was detected, indicating the potential catalysis of the metallic of carbon and SiO236. The weakened peaks of TiO2 at 2θ = 36.6°, 40.3°, 56.4°37 could confirm the formation of bimetallic structure. The detected FeTiO3 and MnFeO4 indicated that the blended Fe, Mn, and Ti can form a bimetal or trimetal bridge structure on the surface of AC. The consumed lattice oxygen of the bridge-structured multi-metal oxides can be replenished easily by gaseous oxygen, which improves the catalytic removal of NO significantly22,38.

Figure 6 displays the Fe 2p, Mn 2p, and Ti 2p XPS spectrum of the new (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC. The Fe 2p3/2 profile has three overlapping peaks at 710.8, 713.1, and 718.7 eV, which are assigned to the Fe3+ bonded with hydroxyl (OH)39,40. The Mn 2p3/2 profiles have three overlapping peaks corresponding to Mn4+ (644.1 eV), Mn3+ (642.5 eV), and Mn2+ (640.9 eV)12,40. Two peaks at 464.8 eV (Ti 2p3/2) and 459.1 eV (Ti 2p1/2) were obtained with a 5.7 eV spin-orbital-splitting belong to the rutile TiO241. The slight shift of binding energy compared with their standard curves in the Fe 2p and Mn 2p spectrums confirm the incorporation of different metal oxides. It was reported that manganese oxides generally contain varieties of labile oxygen, which plays important role in the low-temperature catalytic removal of NO with NH342. Figures 4b and 6 show the labile oxygen and manganese oxidation states (Mn2+, Mn3+, Mn4+) coexisted on the surface of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC. The transformation of coordinated NH3 to NH2 on Mn3+ species initiated the SCR reaction43. The iron oxides can promote the Mn-based catalyst due to its high activity and thermal stability. The redox cycles of Fe3+ ↔ Fe2+ and Mn4+ ↔ Mn3+ ↔ Mn2+ work as a multifunctional electron transfer bridge and release surface oxygen during the catalytic NO removal22, which also makes the catalytic reaction continuable. The improved catalytic performance of (P/Ti-a/b)15@AC is also contributed by the TiO2 species, which shows acidic property and greatly improves the surface NH3 adsorption during flue gas denitrification44.

Surface chemistry after NO removal

The surface chemistry of the NH3-SCR used AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC was studied to obtain additional information. Figure 3b shows that the O–H intensity at 3400 cm−1 of AC strengthened after the NO removal reaction, whereas the (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC showed almost no change. This finding indicates that the blended metal oxides can improve the surface hydrophobicity of the catalyst, and the H2O generated by the reduction removal of NO can be easily carried off at low temperature. In addition, the characterization peaks at 1460 and 875 cm−1 for both AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC were intensified possibly because of the adsorbed NH3 dehydrogenation process (Fig. 3b, d), which was reported as the controlling step of denitrification45,46. On the basis of the XPS results, the additional surface oxygen of the sample after the SCR reaction increased by 4.66% and 0.94% of AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC (Table 3). Both the AC and (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC had a high C–O content after NO removal because of the surface oxygen adsorption during the reaction process9. The π–π* bond of both samples were consumed somehow, which can be attributed to the participation of π bonds in the NH3–NO–O2 reaction47. Consistent with the FTIR, the C=O changed only slightly. No clear difference was detected in the metallic chemistry according to the XRD analysis. This result is consistent with the foregoing conclusion and indicates that the multi-metal structure can perform a stable catalytic activity.

NO removal mechanism

Transient response method (TRM) experiments were conducted to analyze the dynamics of the NH3-SCR process of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC48. Figure 7a shows that the denitrification process responded rapidly with NO, and the outlet NO reduced in 10 min from steady-state to 0 ppm when the inlet NO was completely converted (stage a). When the NO was fed again, however, the outlet NO had a slowly increasing segment (stage d) after a sharp, short increase. This phenomenon can be attributed to the adsorption of NO during the reduction process. The step feed of NO indicates that both the gaseous and absorbed NO participated in selective catalytic removal on the (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC surface, but the adsorbed NO is the main part. Figure 7b shows the NH3 TRM experiment, and the outlet NO showed a two-step increase after the NH3 was turned off. Within a few minutes (approximately 10 min) after NH3 was converted from feedback (stage a1), the NO concentration of outlet gas increased slowly from 170 to 189 ppm, which indicates that some adsorbed NH3 can participate in the SCR reaction22. With the NH3 consumed, the outlet NO gradually increased (stage b1) and remained relatively stable at approximately 465 ppm (stage c1). The 7.0% NO removal without NH3 supply can be due to the surface adsorption and oxidation of NO to form some nitrite and/or nitrate49. After the NH3 supply is fed again, the NO conversion showed almost a linear recovery in 25 min (stage d1). The NO variation with the step-feed NH3 indicates that the NH3 must be adsorbed first to participate in the SCR reaction.

On the basis of the results of this work and previous reports, the Eley–Rideal (E–R) and Langmuir–Hinshelwood (L–H) mechanisms coexist in the NH3-SCR reaction over (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC45,50,51. Both the gaseous and adsorbed NO reacted to the surface adsorbed NH3 due to the carbon and titanium composite structure. In the L–H mechanism pathway, the gaseous NH3 and NO first adsorbed on the (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC surface (Eqs. 2, 3). The adsorbed NO was oxidized to nitrite by the lactic and surface-active oxygen (Eq. 4). The NH3(ads) then reacted with the nitrite to form the NH3NO2 intermediates (Eq. 5) and finally produce the N2 and H2O products through a disproportionate reaction (Eq. 5). In the L–H pathway, the NH3(ads) can be activated by the metal oxide (MnO2) to form the –NH2 (Eq. 6) and can be reacted with the gaseous NO directly via the E–R mechanism (Eq. 7). The preliminarily established entire NO removal mechanism over the (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC composite catalyst is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Table 5 listed some NO removal performance comparison with those of literature that have been reported. At 150 °C, the NO conversion of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC (in the current study) was 66.4%, which is clearly higher than the reported V2O5/AC, Cu/AC-IM, Ce/AC-CNTs et al. catalyst. The Cu/AC-N-IM performed the closest NO conversion is still 9.2% lower than (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC. We know there are many catalysts in related work performed a better NO removal efficiency, while most of them were prepared by the impregnation method as the introduction mentioned (as well the catalysts listed in Table 5), their preparation cost and stability of catalyst were their momentous limitations, especially in industrial application.

Conclusions

In this study, the AC catalysts for low-temperature NO removal using pyrolusite and titanium ore precursor were prepared. The denitrification application shows that pyrolusite and titanium ore blending could promote the catalytic performance clearly because of the more favorable structural properties, surface acidity, and labile oxygen and catalysis of transition metal oxide of AC. Compared with the monomineral modification, the pyrolusite and titanium ore co-blending enhanced the NO removal furtherly. The (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC had the highest NO conversion of 66.4%, improved 16.9%, and 16.0% compared with P15@AC and Ti15@AC. The Ti, Mn, and Fe were good bonded and formed bridge structure, which fasted the lactic oxygen recovery and electron transfer, as well the NH3 adsorption to have a better NO removal performance. The NO removal of (P/Ti-1/2)15@AC followed both the Eley–Rideal and Langmuir–Hinshelwood mechanisms, the gaseous and adsorbed NO reacted simultaneously with the activated NH3 on the surface due to the carbon and titanium composite structure.

References

Tian, M. et al. Increasing importance of nitrate formation for heavy aerosol pollution in two megacities in Sichuan Basin, southwest China. Environ. Pollut. 250, 898–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.098 (2019).

Fawzy, S., Osman, A. I., Doran, J. & Rooney, D. W. Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-020-01059-w (2020).

Sun, Y., Zwolińska, E. & Chmielewski, A. G. Abatement technologies for high concentrations of NOx and SO2 removal from exhaust gases: a review. Crit. Rev. Env. Sci. Technol. 46, 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2015.1063334 (2016).

Busca, G., Lietti, L., Ramis, G. & Berti, F. Chemical and mechanistic aspects of the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by ammonia over oxide catalysts: a review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 18, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-3373(98)00040-X (1998).

Wang, C., Yang, S., Chang, H., Peng, Y. & Li, J. Dispersion of tungsten oxide on SCR performance of V2O5-WO3/TiO2: acidity, surface species and catalytic activity. Chem. Eng. J. 225, 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.04.005 (2013).

Chen, P. et al. Formation and effect of NH4+ intermediates in NH3–SCR over Fe-ZSM-5 zeolite catalysts. ACS Catal. 6, 7696–7700. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.6b02496 (2016).

Wang, L., Cheng, X., Wang, Z., Ma, C. & Qin, Y. Investigation on Fe-Co binary metal oxides supported on activated semi-coke for NO reduction by CO. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 201, 636–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.08.021 (2017).

Szymański, G. S., Grzybek, T. & Papp, H. Influence of nitrogen surface functionalities on the catalytic activity of activated carbon in low temperature SCR of NOx with NH3. Catal. Today 90, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2004.04.008 (2004).

Fu, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, G., Zhang, J. & Guo, Y. NO removal activity and surface characterization of activated carbon with oxidation modification. J. Energy Inst. 90, 813–823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joei.2016.06.002 (2017).

Wang, P. et al. Low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3 over an activated carbon-carbon nanotube composite material prepared by in situ method. RSC Adv. 9, 36658–36663 (2019).

Osman, A. I. Mass spectrometry study of lignocellulosic biomass combustion and pyrolysis with NOx removal. Renewable Energy 146, 484–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.06.155 (2020).

Du, X. et al. Promotional removal of HCHO from simulated flue gas over Mn–Fe oxides modified activated coke. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 232, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.03.034 (2018).

Yao, L., Yang, L., Jiang, W. & Jiang, X. Removal of SO2 from flue gas on a copper modified activated coke prepared by a novel one-step carbonization activation blending method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 15693–15700. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.9b02237 (2019).

Fang, N., Guo, J., Shu, S., Li, J. & Chu, Y. Influence of textures, oxygen-containing functional groups and metal species on SO2 and NO removal over Ce–Mn/NAC. Fuel 202, 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.04.035 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Promoting effect of Nd on the reduction of NO with NH3 over CeO2 supported by activated semi-coke: an in situ DRIFTS study. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5, 2251–2259. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CY01577K (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Low-temperature SCR of NO with NH3 over activated semi-coke composite-supported rare earth oxides. Appl. Surf. Sci. 309, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.04.112 (2014).

Guo, J. et al. Effects of preparation conditions on Mn-based activated carbon catalysts for desulfurization. New J. Chem. 39, 5997–6015. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5nj00873e (2015).

Guo, J. et al. Desulfurization activity of metal oxides blended into walnut shell based activated carbons. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 89, 1565–1575. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.4240 (2014).

Yuan, J. et al. Copper ore-modified activated coke: highly efficient and regenerable catalysts for the removal of SO2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 15731–15739. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.8b03872 (2018).

Yang, L., Jiang, W., Yao, L., Jiang, X. & Li, J. Suitability of pyrolusite as additive to activated coke for low-temperature NO removal. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 93, 690–697. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.5418 (2018).

Zhu, Y., Zhang, Y., Xiao, R., Huang, T. & Shen, K. Novel holmium-modified Fe-Mn/TiO2 catalysts with a broad temperature window and high sulfur dioxide tolerance for low-temperature SCR. Catal. Commun. 88, 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catcom.2016.09.031 (2017).

Yang, S. et al. MnOx supported on Fe–Ti spinel: A novel Mn based low temperature SCR catalyst with a high N2 selectivity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 181, 570–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.08.023 (2016).

Wang, M., Liu, H., Huang, Z. & Kang, F. Activated carbon fibers loaded with MnO2 for removing NO at room temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 256, 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2014.06.108 (2014).

Yang, L., Jiang, X., Huang, T. & Jiang, W. Physicochemical characteristics and desulfurization activity of pyrolusite-blended activated coke. Environ. Technol. 36, 2847–2854. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2015.1050070 (2015).

Fan, L., Chen, J., Guo, J., Jiang, X. & Jiang, W. Influence of manganese, iron and pyrolusite blending on the physiochemical properties and desulfurization activities of activated carbons from walnut shell. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 104, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2013.06.014 (2013).

Mu, W. et al. Novel proposition on mechanism aspects over Fe–Mn/ZSM-5 catalyst for NH3-SCR of NOx at low temperature: rate and direction of multifunctional electron-transfer-bridge and in situ DRIFTs analysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 6, 7532–7548. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CY01510G (2016).

Osman, A. I., Farrell, C., Al-Muhtaseb, A. A. H., Harrison, J. & Rooney, D. W. The production and application of carbon nanomaterials from high alkali silicate herbaceous biomass. Sci. Rep. 10, 2563. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59481-7 (2020).

Osman, A. I. et al. Upcycling brewer’s spent grain waste into activated carbon and carbon nanotubes for energy and other applications via two-stage activation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 95, 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.6220 (2020).

Teng, L.-H. & Tang, T.-D. IR study on surface chemical properties of catalytic grown carbon nanotubes and nanofibers. J. Zhejiang Univ. SC. A 9, 720–726. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.A071503 (2008).

Hu, S. & Hsieh, Y.-L. Preparation of activated carbon and silica particles from rice straw. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2, 726–734. https://doi.org/10.1021/sc5000539 (2014).

Baykal, A. et al. Acid functionalized multiwall carbon nanotube/magnetite (MWCNT)–COOH/Fe3O4 hybrid: synthesis, characterization and conductivity evaluation. J. Inorg. Organomet. P. 23, 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-013-9839-4 (2013).

Liu, Z. et al. In situ exfoliated, edge-rich, oxygen-functionalized graphene from carbon fibers for oxygen electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606207. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201606207 (2017).

Lin, Q., Li, J., Ma, L. & Hao, J. Selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 over Mn–Fe/USY under lean burn conditions. Catal. Today 151, 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2010.01.026 (2010).

Jo, Y. B. et al. NH3 selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of nitrogen oxides (NOx) over activated sewage sludge char. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 28, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-010-0283-7 (2011).

Wang, T. et al. Promotional effect of iron modification on the catalytic properties of Mn–Fe/ZSM-5 catalysts in the Fast SCR reaction. Fuel Process. Technol. 169, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2017.09.029 (2018).

Mohamed, M. J. S. & Selvakumar, N. J. E. J. O. S. R. Effect of strain in X-ray line broadening of MoSi2–10% SiC ceramic nanocomposites by williamson hall method. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 79, 82–88 (2012).

Yates, H. M., Nolan, M. G., Sheel, D. W. & Pemble, M. E. The role of nitrogen doping on the development of visible light-induced photocatalytic activity in thin TiO2 films grown on glass by chemical vapour deposition. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 179, 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2005.08.018 (2006).

Zhan, S. et al. Facile preparation of MnO2 doped Fe2O3 hollow nanofibers for low temperature SCR of NO with NH3. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 20486–20493. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA04807E (2014).

Tan, P. Active phase, catalytic activity, and induction period of Fe/zeolite material in nonoxidative aromatization of methane. J. Catal. 338, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2016.01.027 (2016).

Chen, Z. et al. Low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3 over Fe–Mn mixed-oxide catalysts containing Fe3Mn3O8 phase. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 202–212. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie201894c (2012).

Li, L. et al. Sub-10 nm rutile titanium dioxide nanoparticles for efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen production. Nat. Commun. 6, 5881. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6881 (2015).

Jiang, B., Liu, Y. & Wu, Z. Low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NO on MnOx/TiO2 prepared by different methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 162, 1249–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.06.013 (2009).

Kijlstra, W. S., Brands, D. S., Poels, E. K. & Bliek, A. Mechanism of the selective catalytic reduction of no by NH3 over MnOx/Al2O3. 1. Adsorption and desorption of the single reaction components. J. Catal. 171, 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcat.1997.1788 (1997).

Jin, R. et al. The role of cerium in the improved SO2 tolerance for NO reduction with NH3 over Mn–Ce/TiO2 catalyst at low temperature. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 148, 582–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.09.016 (2014).

Hao, Z. et al. The role of alkali metal in α-MnO2 catalyzed ammonia-selective catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 58, 6351–6356. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201901771 (2019).

He, G. et al. Polymeric vanadyl species determine the low-temperature activity of V-based catalysts for the SCR of NOx with NH3. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau4637. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4637 (2018).

García, P., Coloma, F., Salinas Martínez de Lecea, C. & Mondragón, F. Nitrogen complexes formation during NO–C reaction at low temperature in presence of O2 and H2O. Fuel Process. Technol. 77–78, 255–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-3820(02)00014-0 (2002).

Nova, I., Ciardelli, C., Tronconi, E., Chatterjee, D. & Bandl-Konrad, B. NH3-SCR of NO over a V-based catalyst: low-T redox kinetics with NH3 inhibition. Aiche J. 52, 3222–3233. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.10939 (2006).

Li, Y. et al. Low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3 over Mn2O3-doped Fe2O3 hexagonal microsheets. ACS App. Mater. Interfaces 8, 5224–5233. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b10264 (2016).

Damma, D., Ettireddy, P. R., Reddy, B. M. & Smirniotis, P. G. A review of low temperature NH3-SCR for removal of NOx. Catalysts 9, 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal9040349 (2019).

Li, G. et al. Reaction mechanism of low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of nox over Fe–Mn oxides supported on fly-ash-derived SBA-15 molecular sieves: structure–activity relationships and in Situ DRIFT analysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 20210–20231. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b03135 (2018).

Boyano, A. et al. A comparative study of V2O5/AC and V2O5/Al2O3 catalysts for the selective catalytic reduction of NO by NH3. Chem. Eng. J. 149, 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2008.10.022 (2009).

Shen, B., Chen, J., Yue, S. & Li, G. A comparative study of modified cotton biochar and activated carbon based catalysts in low temperature SCR. Fuel 156, 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2015.04.027 (2015).

Ma, Z., Yang, H., Li, Q., Zheng, J. & Zhang, X. Catalytic reduction of NO by NH3 over Fe–Cu–OX/CNTs–TiO2 composites at low temperature. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 427–428, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2012.03.028 (2012).

Chuang, K.-H., Lu, C.-Y., Wey, M.-Y. & Huang, Y.-N. NO removal by activated carbon-supported copper catalysts prepared by impregnation, polyol, and microwave heated polyol processes. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 397, 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2011.03.003 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51908383) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M653408).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. and L.Yao wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures and tables; L.Y., and W.J.J. designed and carried out the experiments; X.J. and W.J.J. discussed the related results; L.Y. obtained funding; Y.G.L. and L.Y. designed the research and discussed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Yao, L., Lai, Y. et al. Co-blending modification of activated coke using pyrolusite and titanium ore for low-temperature NOx removal. Sci Rep 10, 19455 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76592-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76592-3