Abstract

In this paper, efficient analysis of the plane wave scattering by periodic arrays of magnetically-biased graphene strips (PAMGS) is performed using the semi-numerical, semi-analytical method of lines (MoL). In MoL, all but one independent variable is discretized to reduce a system of partial differential equations to a system of ordinary differential equations. Since the solution in one coordinate direction is obtained analytically, this method is time effective with a fast convergence rate. In the case of a multi-layered PAMGS, the governing equations of the problem are discretized concerning periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) in the transverse direction. The reflection coefficient transformation approach is then used to obtain an analytical solution in the longitudinal direction. Here, magnetically-biased graphene strips are modeled as conductive strips with a tensor surface conductivity which is electromagnetically characterized with tensor graphene boundary condition (TGBC). The reflectance and transmittance of different multi-layered PAMGS are carefully obtained and compared with those of other methods reported in the literature. Very good accordance between the results is observed which confirms the accuracy and efficiency of the proposed method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graphene, as a 2D material with hexagonal honeycomb lattice, has remarkable mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties such as astonishing strength and stiffness, optical transparency, high electronic mobility, and tunable surface conductivity1,2,3,4. The tunability of its surface conductivity by an applying electric or magnetic field bias is the main advantage of graphene over metals, which leads to the design of tunable devices including tunable THz absorbers5,6, graphene frequency selective surface with tunable polarization rotation characteristics7, etc. Moreover, the magnetically-biased graphene has anisotropic surface conductivity and shows non-reciprocal gyrotropy at microwave and optical frequencies8, which makes it a good candidate for designing nonreciprocal components9 and achieving enhanced Faraday rotation10.

To model the electromagnetic characteristics of graphene various methods have been implemented numerically. The graphene has been characterized using a circuit model through the partial element equivalent circuit (PEEC) method by Coa et al.11. The discontinuous Galerkin time domain (DGTD) method for the analysis of magnetically-biased graphene is reported by Li et al.12. The finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method13 and the MoL14 are also reported for modelling magnetized graphene. Besides, magnetically biased graphene sheets are analyzed analytically by Heydari et al.15.

Alternatively, graphene-based periodic structures (GPS) with fascinating properties like perfect absorption of light in a specific range of frequency16,17 take advantage of the unique electromagnetic properties of graphene. The GPSs with numerous applications including THz absorbers18, THz filter19, and graphene-based frequency selective surfaces20, to name a few, have been reported in the literature. As a result, a fast and accurate method for the efficient analysis of GPSs is in need.

The study of electromagnetic waves interaction with periodic arrays of graphene has attracted great attention to the researchers recently. Different numerical methods, including the method of moments (MoM)21, finite-difference time-domain (FDTD)22, integral equations (IE)23, and Fourier modal method (FMM)24,25,26 have been reported for the diffraction analysis of GPSs in the absence of magnetic field bias while less effort has been made in case of magnetically-biased GPSs20,27.

In this paper, the semi-numerical, semi-analytical MoL has been provided for the efficient analysis of the plane wave scattering by PAMGS. In this method, we use of PBCs to take the periodicity of the PAMGS into account. Hence, the fields and the derivatives are to be discretized with finite differences according to the PBCs. Besides, the constitutive parameters of the cross section as well as the surface conductivity of graphene strips are discretized. In those parts of the cross-section where there is no graphene, the conductivity value is zero. Hence, there is no need to introduce approximate boundary condition at the interface of two adjacent layers where graphene exists as done by Khoozani et. al27.

Moreover, unlike fully numerical methods, the solution of the problem in one coordinate direction is obtained analytically in MoL which means there is no need to use absorbing boundary condition (ABC) such as perfectly matched layers (PML) in this direction. Besides, the analytical nature of the method saves a lot of computing time compared to fully numerical methods. The reflection coefficient transformation approach is introduced to obtain an analytical solution in this direction. In this approach, the structure under the study is divided into homogeneous layers and the known reflection coefficient in the last layer is transformed through layers and interfaces to obtain the reflectance. Having known the reflection coefficient in each layer, the transmission coefficient is obtained by transforming the fields in the opposite direction.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: First, we present a brief description of the graphene properties. Then, we continue with the basic formulation of the problem. In this section, the MoL is introduced concisely. Afterwards, the plane wave incidence on a PAMGS for the two special cases of normal and oblique incidence is investigated. The reflection and transmission coefficients of a multi-layered PAMGS are obtained in the next subsection. Next, the numerical results of different PAMGSs obtained using the proposed method are presented.

Graphene conductivity model

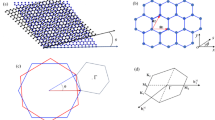

Consider a graphene sheet in the xy plane with a magnetic field bias \(B=B_0{\hat{z}}\) as shown in Fig. 1a. As the result of its gapless electronic band structure and one-atom thickness, graphene can be treated as semiconductors28,29 characterizing with an anisotropic surface conductivity to be obtained through a quantum mechanical analysis using Kubo formulation8,30,31. However, in the case of magnetic field bias, there exists an excitonic energy gap which is opened due to the interaction of electrons with the magnetic field that can be significant at low temperature. At high temperature, the carrier density increases and consequently the screening effect enhances. Hence, the gap disappears and the graphene sheet’s electronic band structure remains gapless32.

The anisotropic nature of graphene’s conductivity can be interpreted by the electron motion in the xy plane under an electric field as shown in Fig. 1b8. For the case \({\mathbf{E} }=E_y{\hat{y}}\), the electric force \(F_e\) will be in the \(-{\hat{y}}\) direction. The acceleration of the electron in \(-{\hat{y}}\) direction causes a Lorentz force \(F_m\) in \({\hat{x}}\) direction. Consequently, the combination of these two forces results in two current components in \(-{\hat{x}}\) and \({\hat{y}}\) directions. The case of \({\mathbf{E }}=E_x{\hat{x}}\) can be treated similarly in which the two current components are produced in \({\hat{x}}\) and \({\hat{y}}\) directions. Thus, the relation between the resultant surface currents and tangential electric fields is described as follows8

in which \(\sigma _{xx}=\sigma _{yy}=\sigma _L\) and \(\sigma _{xy}=-\sigma _{yx}=\sigma _T\) are the longitudinal (parallel to the electric field) and transversal (perpendicular to the electric field) components consisting of two parts modeling the intraband and interband electron transitions. However, in THz regime where \(\hbar \omega <2 \mu _c\), the intraband transition is dominant8,27. Here, the optical properties of graphene are similar to those of Drude-type materials and as the result the quantum mechanical closed form expressions for \(\sigma _L\) and \(\sigma _T\) reduce to the classic Drude model as follows8,27,33

with

where \(\hbar\) is the reduced Plancks constant, e is the electron charge, \(\mu _c\) is the chemical potential, \(\tau\) is relaxation time, \(\omega _c=eB_0v_F^2/\mu _c\) is the cyclotron frequency, \(v_F=10^6 m/s\) is the Fermi velocity, \(n_s\) is the carrier density, and T is the Kelvin temperature.

Alternatively, since the graphene sheet is modeled with a tensor surface conductivity, it can be electromagnetically treated as an special impedance boundary condition at the interface of adjacent layers called tensor graphene boundary condition (TGBC). The TGBCs are given by

in which \({\hat{n}}\) is the unit vector normal to the interface pointing from media 2 to media 1, \((\vec {E}_1, \vec {H}_1)\) and \((\vec {E}_2, \vec {H}_2)\) are the electric and magnetic fields in media 1 and 2, respectively.

These boundary conditions are then used in the next subsections to derive the reflection coefficient transformation formula through interfaces. Note that a time dependence of \(e^{j\omega t}\) is assumed throughout this paper.

Formulation of the problem

Consider a PAMGS with graphene strips of width \(W_g\) and period length of D as shown in Fig. 2a in which the graphene strips are assumed to be infinitely long in the y-direction.

Despite graphene sheets with gapless electronic band structures, one-dimensional graphene strips with finite width have been proposed to obtain tunable band gaps where the energy gap is controlled by the strip width28,29. Besides, unlike infinite graphene sheets, graphene strips have non-uniform carrier density \(n_s\) which means that the electrons near the edges of the strips experience different forces in compare to those in the middle of the strips. As the result, two different modes can be supported by the graphene strips namely edge modes and bulk modes with high localization near the edges and in the middle of the strips, respectively33. For chemically doped graphene, the net charge is zero. Here, the edge effects are confined to a strip width in order of the dopant’s Wigner-Seitz radius. Hence, for wide enough strips these edge effects can be neglected and the graphene strips can be modeled with the same conductivity parameters as those of an infinite sheet33.

The method of lines

To start the analysis of a PAMGS and to consider its periodicity in x-direction, we normalize the electromagnetic fields with respect to the phase as follows:

in which \(\psi _{0i}(x,y,z)\) is the non-normalized electromagnetic field component, \(k_x\) is the propagation constant of the incident wave vector in x-direction and \(\psi _i(x,y,z)\) is either \(\textit{E}_i\) or \(\textit{H}_i\) with \(i=x, y, z\). These functions are periodic in the x-direction with period D.

Now we substitute Eq. (5) into Maxwell’s curl equations, which results in

in which \({\bar{i}}=k_0i\) and \({\tilde{H}}_i=\eta _0H_i\) where \(k_0=\omega \sqrt{\mu _0 \epsilon _0}\) and \(\eta _0=\sqrt{\mu _0/\epsilon _0}\) are the free space wave number and wave impedance, respectively. Also, \(D_{{\bar{y}}}=\partial /\partial {\bar{y}}\) and \(D_{{\bar{x}}}=jk_{{\bar{x}}}+e^{jk_{{\bar{x}}}{\bar{x}}}\partial /\partial {\bar{x}}\) with \(k_{{\bar{x}}}=k_x/k_0\).

Next, we eliminate the longitudinal field components \(E_z\) and \({\tilde{H}}_z\) in Eqs. (6) and (7) to obtain generalized transmission line (GTL) equations as follows34

In this step, we discretize the fields and the derivatives in Eqs. (8) and (9) using finite differences. To this end, consider the unit cell of the PAMGS as shown in Fig. 2b with period length of D and \(N_x\) discretization lines within the period. To start, the periodic functions of Eq. (5) are discretized as follows

in which the \({\mathbf{S} }_e\) and \({\mathbf{S }}_h\) are diagonal matrices of size \(N_x\times N_x\) whose elements are \(e^{jk_{{\bar{x}}}ih_{{\bar{x}}}}\) and \(e^{jk_{{\bar{x}}}(i+0.5)h_{{\bar{x}}}}\) for \(i=1:N_x\), respectively. The discretized quantities are displayed in bold. Accordingly, the discretize field components of \({\mathbf{E }}_y\) and \({\mathbf{H }}_y\) are saved in column vectors of size \(N_x\times 1\). Then, the phased normalized derivatives in the discretized domain are obtained as34

with

in which \(s=e^{j\frac{k_xh_x}{2}}\). Hence, \({\mathbf{D} }_{{\bar{x}}}^e={\mathbf{D }}_{{\bar{x}}}{\mathbf{E }}_y\) and \({\mathbf{D} }_{{\bar{x}}}^h={\mathbf{D} }_{{\bar{x}}}{\mathbf{H }}_y\) are constructed according to Eq. (11).

Besides, since there is no variation in the y-direction we put \({\mathbf{D }}_{{\bar{y}}}=[0]_{N_x\times N_x}\) in Eqs. (8) and (9). As the result, the discretized GTL equations are obtained as follows:

where \({\mathbf{I} }\) is an identity matrix of \(N_x\).

Using the definition \({\mathbf{E }}=[{\mathbf{E }}_y \quad {\mathbf{E }}_x]^t\) and \({\tilde{\mathbf{H }}}=[-\tilde{\mathbf{H }}_x \quad \tilde{\mathbf{H }}_y]^t\) where the superscript t refers to the matrix transpose, the solution to Eqs. (13) and (14) are given by34

in which \({\mathbf{T }}_E\) is a square matrix whose columns are the eigenvectors of matrix \({\mathbf{Q }}_E={\mathbf{R }}_E{\mathbf{R} }_H\). The corresponding eigenvalues of \({\mathbf{Q} }_E\) form the diagonal matrix of \(\varvec{\Gamma ^2}\). Furthermore, it is proved that34

where \(\varvec{\beta }^2=\varvec{-\Gamma }^2\). Besides, \((\bar{{\mathbf{E }}}_f,\bar{{\mathbf{E} }}_b)\) and \((\bar{{\mathbf{H }}}_f,\bar{{\mathbf{H }}}_b)\) are forward and backward amplitudes of propagating electric and magnetic fields eigenmodes, respectively.

Plane wave incidence

According to Maxwell’s curl equations \(\bigtriangledown \times \vec {E}=-j\omega \mu _0 \vec {H}\) and \(\bigtriangledown \times \vec {H}=j\omega \varepsilon _0 \vec {E}\), for a plane wave with \(\vec {E}=\vec {E}_0e^{-j(k_x{\hat{x}}+k_z{\hat{z}})}\) and \(\vec {H}=\vec {H}_0e^{-j(k_x{\hat{x}}+k_z{\hat{z}})}\), the relation between transverse components of the electric and magnetic fields is given by

where the subscript t refers to transverse components. In what follows, we investigate two special cases of normal and oblique incidence on a PAMGS using MoL.

Normal incidence

According to Fig. 3a, for the case of normal incidence we put \(k_x=0\) in Eqs. (13) and (14) and compute the corresponding \({\mathbf{T }}_E\), \({\mathbf{T }}_H\) and \(\varvec{\Gamma }\) in the two half spaces. Next, we define incident, reflected and transmitted electric and magnetic fields as follows:

By definition

To obtain the unknown reflection and transmission coefficients of the PAMGS, the TGBCs at the interface of layers 1 and 2 must be applied. The discretized form of Eq. (4) reads as

where \({\mathbf{A} }\) is a matrix of size \(N_x\times N_x\) defined by

in which \({\mathbf{I }}_g\) and \({\mathbf{Z} }_{Ng}\) are identity and zero matrices of size \(N_g\) and \((0.5(N_x-N_g))\), respectively where \(N_g\) is the number of discretization lines on graphene strip. Moreover, according to Fig. 2b, \({\mathbf{E} }_y\) and \(\mathbf{E }_x\) are discretized in different positions hence adding or subtracting them directly to obtain \(\tilde{\mathbf{H }}_x\) or \(\tilde{\mathbf{H }}_y\) is not allowed. As the result, the interpolation matrices \(\mathbf{M }_1\) and \(\mathbf{M }_2\) are introduced35 to obtain the field components in the correct position. Using the same definition for \(\mathbf{E }\) and \(\tilde{\mathbf{H }}\) as those of Eqs. (15) and (16), we rewrite Eq. (22) as follows

Substituting \(\mathbf{E }_1=\mathbf{E }^{inc}+\mathbf{E }^{ref}\) and \(\mathbf{E }_2=\mathbf{E }^{tran}\) as well as \(\mathbf{H }_1=\mathbf{H }^{inc}+\mathbf{H }^{ref}\) and \(\mathbf{H }_2=\mathbf{H }^{tran}\) according to Eq. (20) in Eq. (24) and considering that \(\mathbf{E }^{ref}=\mathbf{r }\mathbf{E }^{inc}\), we have

Furthermore, according to Eq. (18) for the case of normal incidence where \(k_z=k_0\) we have

where \(i=1,2\) and the forward and backward magnetic fields are normalized to free space wave impedance \(\eta _0\). Substituting Eq. (26) into Eq. (25), the reflection and transmission coefficients are obtained as

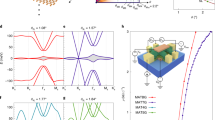

For \(W_g=D\), the PAMGS shown in Fig. 3a reduces to an infinite graphene sheet at the interface of two infinite layers. In this case the reflection and transmission coefficients can be obtained analytically8. Figure 4a compares the obtained Co- and Cross-polarized reflection and transmission coefficients of a free standing infinite graphene sheet using MoL and analytical formulation. Besides, in order to examine the accuracy of the proposed method we calculated the relative error between our proposed method and those of analytical formulations for two cases of co- and cross-polarized transmittance as shown in Fig. 4b. The analytical results have been assumed as the reference in calculating this relative error. According to this figure, there is an excellent agreement between both sets of the results.

(a) Comparison of reflection and transmission coefficients of a free standing infinite graphene sheet obtained using both MoL (solid curves) and analytical formulation (dashed lines) for \(\mu _c=0.5\) eV, \(B_0=0.5\) T, \(\tau =0.1\) ps and \(T=300\) K, (b) Relative error between the MoL results and analytical formulations in the calculation of Co- and Cross-polarized transmission coefficients.

Oblique incidence

For the case of oblique incidence, the two particular cases of TE(H) and TM(E) polarized waves are investigated simultaneously. According to Fig. 3b, we put \(k_z=k_0cos(\theta _i)\) with \(i=1,2\) in Eqs. (18) and (19) which leads to

where

with

Taking Eqs. (29) to (31) into account and following the same procedure as done in the previous case, the reflection and transmission coefficients with very small modification compared to normal incidence are obtained as follows

where

It is worth mentioning that since the effect of the radiation angle \((\theta _1)\) on reflectance and transmittance is considered analytically through Eqs. (29) to (31), there is no need to recalculate the eigenvector matrices \((\mathbf{T }_{Ei}, \mathbf{T }_{Hi})\) in case of oblique incidence. The reflection and transmission coefficients of a free standing infinite graphene sheet under oblique incidence with \(\theta _1=30^\circ\) are obtained using Eqs. (32) and (33) and compared with those of analytical solutions as shown in Fig. 5a. Again, we computed the relative error between our results and those of analytical formulations with analytical results being the reference as shown in Fig. 5b. This figure confirms the accuracy of our proposed method.

(a) Comparison of reflection and transmission coefficients of a free standing infinite graphene sheet obtained using both MoL (solid curves) and analytical formulation (dashed lines) for \(\mu _c=0.5\) eV, \(B_0=0.5\) T, \(\tau =0.1\) ps and \(T=300\) K at oblique incidence, (b) Relative error between the MoL results and analytical formulations in the calculation of TE and TM transmission coefficients.

Multilayer PAMGS

In the analysis of a multilayer PAMGS as shown in Fig. 6, we use the reflection coefficient transformation approach to obtain the reflection and transmission coefficients of the whole periodic structure. In this approach the output reflection coefficient \((\mathbf{r }_{out})\) is assumed to be known and is to be transformed through layers and interfaces to obtain the input reflection coefficient \((\mathbf{r }_{in})\).

By definition

where i is the number of layer. On the other hand, \(\bar{\mathbf{E }}_{f}(z)=e^{-\varvec{\Gamma }{\bar{z}}}\bar{\mathbf{E }}_{f}(0)\) and \(\bar{\mathbf{E }}_b(z)=e^{\varvec{\Gamma }{\bar{z}}}\bar{\mathbf{E }}_b(0)\). Hence, according to Eq. (36) the reflection coefficient is transformed through the layers by

For \(i=N\) we have \(\mathbf{r }_{(i+1)^-}=\mathbf{r }_{out}\) which is set to zero in case of a semi-infinite layer. To calculate the reflection coefficient transformation formula through interfaces, the TGBCs have to be applied as follows

Now we substitute Eq. (29) into Eq. (38) and rearrange the formulas to obtain \(\mathbf{r }_{i^-}\) as a function of \(\mathbf{r }_{i^+}\) as follows

with

Using the extracted recursive formulas for \(i=N:1\), the reflection coefficient of the multilayer PAMGS as \(\mathbf{r }_{in}=\mathbf{r }_{1^-}\) is obtained.

To obtain the transmission coefficient of the structure we should transform the fields in the opposite direction from the input to the output as follows

By definition

Hence,

Having known the reflection and transmission coefficients in each layer as well as \(\bar{\mathbf{E }}_{fin}\) the complete solution of the structure is attainable.

In short, we considered graphene as an especial impedance boundary condition at the interface of two adjacent layers due to its 2D structure and computed the reflection coefficient transformation formula through the interfaces, accordingly. Other 2D materials including Group-IV monoelemental honeycomb materials and binary compounds of group III-V elements can be treated similarly provided that we can model them as an appropriate boundary condition.

Numerical results of different PAMGSs

To validate the proposed method, the numerical results for two different PAMGSs are obtained and compared with those of other methods. As the first example, the Faraday rotation effect achieved by a PAMGS as shown in Fig. 7a is investigated using MoL and compared with Fourier-Floquet plane wave expansion method36. Then, a multilayer PAMGS as a tunable THz absorber shown in Fig. 7b is analyzed. In this case, the obtained results are compared with those of the circuit model theory method. In both cases, the two sets of the results are in good accordance.

Faraday rotation

The PAMGS shown in Fig. 7a is illuminated with a x-directed wave at normal incidence. In presence of a magnetic field bias, the direction of the transmitted electric field is deviated from that of the incident wave by angle \(\theta _F\) called as Faraday rotation angle. By definition36

where \(t_{cross}=t_{yx}\) and \(t_{co}=t_{xx}\) are the transmission coefficients in y- and x-direction due to an x-directed incident wave, respectively.

On the other hand, the transmission efficiency is defined by36

in which \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are the refractive indices of incident and transmitted regions, respectively.

The Faraday rotation angle and the transmission efficiency of the structure shown in Fig. 7a with \(D=2W_g=1 \mu m\) and \(\varepsilon _r=4\) as a function of frequency are obtained using MoL and compared with those of Ref.36 and a commercial software as shown in Fig. 8a,b, respectively. In order to compare our numerical results with those obtained from commercial software, the structure shown in Fig. 7a is simulated using High Frequency Structural Simulator (HFSS) with its modal solution solver. It is worth mentioning that for this structure the number of discretization lines is set to \(N_x=50\) for the MoL results to be converged. Moreover, to match the HFSS results to that of MoL, maximum Delta S is set to 0.0005 and took more than 40 minutes to run on an Intel Core i7 8700K CPU, 32 GB RAM desktop computer while the MoL took less than 4 seconds on the same computer. As it is seen the three sets of results agree very well. According to Fig. 8a,b the minimum transmittance occurs where the \(\theta _F\) changes sign.

Comparison of (a) Faraday rotation angle and (b) transmission efficiency of the structure under study obtained using MoL (solid lines), those of Fourier-Floquet plane wave expansion method (dashed lines) and HFSS commercial software (dot lines) at different magnetic fields bias for \(\mu _c=0.2\) eV, \(\tau =0.1\) ps and \(T=300\) K.

Moreover, to investigate the effect of the chemical potential on reflectance and transmittance, the co- and cross-polarized reflectance and transmittance for different \(\mu _c\) are obtained and shown in Fig. 9a,b, respectively. The resonance frequency of the PAMGS is blue-shifted as \(\mu _c\) increases.

Tunable THz absorber

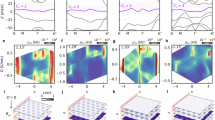

The next example deals with a tunable THz absorber reported made of a multilayer PAMGS as shown in Fig.7b6. This absorber is composed of a perfect electric conductor (PEC), a continuous graphene sheet (CGS), and the periodic array of graphene strips (PAGS). The PEC, CGS and PAGS are separated with an intermediate dielectric layer. The PEC is used to suppress the transmission and increase the absorption.

To evaluate the efficiency and accuracy of the proposed MoL in analyzing this absorber with \(D=23.6 \mu m\), \(W_g=18.28 \mu m\), \(d_1=300 \mu m\), \(d_2=0.3 \mu m\) and \(\varepsilon _r=2.34\), the absorption of the structure as a function of frequency is obtained and compared with those of circuit model theory approach reported in literature6 as shown in Fig. 10. The graphene sheet and strips are assumed to be isotropic (\(B_0=0\)) and the structure is illuminated by an x-directed wave with normal incidence. As illustrated in Fig. 10, the obtained results using MoL agree very well with those of circuit model theory approach.

Absorption spectra of the tunable THz absorber of Fig.7b for \(\mu _{c(CGS)}=0.25\) eV, \(\mu _{c(PAGS)}=0.125\) eV, \(\tau =0.1\) ps and \(T=300\) K.

Next, the effect of incident angle on absorption for both TE and TM polarizations is investigated. As shown in Fig. 11a,b, increasing the incident angle causes a blue shift in absorption peaks. Besides, the absorption of the structure for both TE and TM polarizations are almost the same. As the result, this absorber can be referred to as a polarization independent absorber6.

Absorption spectra of the tunable THz absorber of Fig.7b with oblique (a) TM and (b) TE polarized incident wave obtained by MoL for \(\mu _{c(CGS)}=0.25\) eV, \(\mu _{c(PAGS)}=0.125\) eV, \(\tau =0.1\) ps and \(T=300\) K.

Conclusion

In summary, we used the semi-numerical, semi-analytical method of lines (MoL) for the efficient analysis of the plane wave scattering in the most general case of oblique incidence for both TE and TM polarizations by multilayer periodic arrays of magnetically biased graphene strips (PAMGS). First, we discretized the governing equations in transverse directions concerning the periodic boundary condition using finite differences. Then, the reflection coefficient transformation approach was used to obtain the reflectance and transmittance of the multilayer structure analytically. Since the graphene parameters are discretized with finite differences in transverse directions, we set the surface conductivity to zero where graphene is absent. Hence, there is no need to introduce approximate boundary condition to model graphene. On the other hand, due to the semi-analytical nature of the method, there is no demand for the use of absorbing boundary conditions in the longitudinal direction unlike fully numerical methods. These advantages have made MoL a powerful computational tool for analyzing multi-layered graphene-based periodic structures. To validate the proposed method, numerical results for different PAMGSs are obtained using the proposed method and compared with those obtained by other methods reported in the literature. In all cases, the two sets of the results agree very well, which confirms the validity of the method. Analyzing 3D graphene-based periodic structures with 2D periodicity will be the subject of our future work.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Novoselov, K. .S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Novoselov, K. .S. et al. Two-dimensional gas of massless dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 438, 197–200 (2005).

Geim, A. K. Graphene: status and prospects. Science 324, 1530–1534 (2009).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. In Nanoscience and technology: a collection of reviews from nature journals, 11–19 (World Scientific, 2010).

Chen, D., Yang, J., Zhang, J., Huang, J. & Zhang, Z. Section 1tunable broadband terahertz absorbers based on multiple layers of graphene ribbons. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–8 (2017).

Biabanifard, M. & Abrishamian, M. S. Multi-band circuit model of tunable thz absorber based on graphene sheet and ribbons. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 95, 256–263 (2018).

Li, X., Lin, L., Wu, L.-S., Yin, W.-Y. & Mao, J.-F. A bandpass graphene frequency selective surface with tunable polarization rotation for thz applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 65, 662–672 (2016).

Sounas, D. L. & Caloz, C. Gyrotropy and nonreciprocity of graphene for microwave applications. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 60, 901–914 (2012).

Chamanara, N., Sounas, D. & Caloz, C. Non-reciprocal magnetoplasmon graphene coupler. Opt. Express 21, 11248–11256 (2013).

Liang, Y., Xiang, Y. & Dai, X. Enhancement of graphene faraday rotation in the one-dimensional topological photonic crystals. Opt. Express 28, 24560–24567 (2020).

Cao, Y. S., Jiang, L. J. & Ruehli, A. E. An equivalent circuit model for graphene-based terahertz antenna using the peec method. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 64, 1385–1393 (2016).

Li, P. & Jiang, L. J. Modeling of magnetized graphene from microwave to thz range by dgtd with a scalar rbc and an ade. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 63, 4458–4467 (2015).

Wang, X.-H., Yin, W.-Y. & Chen, Z. Matrix exponential fdtd modeling of magnetized graphene sheet. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 12, 1129–1132 (2013).

Mehrdadian, A., Ardakani, H. H. & Forooraghi, K. Analysis of two dimensional graphene-based multilayered structures using the extended method of lines. IEEE Access 6, 31503–31515 (2018).

Heydari, M. B. & Samiei, M. H. V. An analytical study of magneto-plasmons in anisotropic multi-layer structures containing magnetically biased graphene sheets. Plasmonics 1–16 (2020).

Kumar, P., Lakhtakia, A. & Jain, P. K. Graphene pixel-based polarization-insensitive metasurface for almost perfect and wideband terahertz absorption. JOSA B 36, F84–F88 (2019).

Lee, S., Tran, T. Q., Heo, H., Kim, M. & Kim, S. A proposal of a perfect graphene absorber with enhanced design and fabrication tolerance. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 (2017).

Xiao, B., Gu, M. & Xiao, S. Broadband, wide-angle and tunable terahertz absorber based on cross-shaped graphene arrays. Appl. Opt. 56, 5458–5462 (2017).

Nasari, H. & Abrishamian, M. S. All-optical tunable notch filter by use of kerr nonlinearity in the graphene microribbon array. JOSA B 31, 1691–1697 (2014).

Guo, Y., Zhang, T., Yin, W.-Y. & Wang, X.-H. Improved hybrid fdtd method for studying tunable graphene frequency-selective surfaces (gfss) for thz-wave applications. IEEE Tran. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 5, 358–367 (2015).

Fallahi, A. & Perruisseau-Carrier, J. Design of tunable biperiodic graphene metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. B 86, 195408 (2012).

Wu, S., Sun, Y., Chi, M. & Chen, X. Extraordinary optical transmission through periodic drude-like graphene sheets using fdtd algorithms and its unconditionally stable approximate crank-nicolson implementation. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–16 (2020).

Shapoval, O. V., Gomez-Diaz, J. S., Perruisseau-Carrier, J., Mosig, J. R. & Nosich, A. I. Integral equation analysis of plane wave scattering by coplanar graphene-strip gratings in the thz range. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 3, 666–674 (2013).

Khavasi, A. Fast convergent fourier modal method for the analysis of periodic arrays of graphene ribbons. Opt. Lett. 38, 3009–3012 (2013).

Nekuee, S. A. H., Khavasi, A. & Akbari, M. Fourier modal method formulation for fast analysis of two-dimensional periodic arrays of graphene. JOSA B 31, 987–993 (2014).

Hwang, R.-B. Highly improved convergence approach incorporating edge conditions for scattering analysis of graphene gratings. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–10 (2020).

Khoozani, P. K., Maddahali, M., Shahabadi, M. & Bakhtafrouz, A. Analysis of magnetically biased graphene-based periodic structures using a transmission-line formulation. JOSA B 33, 2566–2576 (2016).

Chung, H., Lee, M., Chang, C. & Lin, M.-F. Exploration of edge-dependent optical selection rules for graphene nanoribbons. Opt. Express 19, 23350–23363 (2011).

Chung, H.-C., Chang, C.-P., Lin, C.-Y. & Lin, M.-F. Electronic and optical properties of graphene nanoribbons in external fields. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 7573–7616 (2016).

Gusynin, V., Sharapov, S. & Carbotte, J. On the universal ac optical background in graphene. New J. Phys. 11, 095013 (2009).

Gusynin, V., Sharapov, S. & Carbotte, J. Magneto-optical conductivity in graphene. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 19, 026222 (2006).

Hanson, G. W. Dyadic green’s functions for an anisotropic, non-local model of biased graphene. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 56, 747–757 (2008).

Sounas, D. L. & Caloz, C. Edge surface modes in magnetically biased chemically doped graphene strips. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 231902 (2011).

Pregla, R. Analysis of electromagnetic fields and waves: the method of lines Vol. 21 (Wiley, 2008).

Mehrdadian, A. & Forooraghi, K. Analysis of graphene-based multilayered three-dimensional structures by the extended method of lines. IEEE Access 6, 20937–20949 (2018).

Tymchenko, M., Nikitin, A. Y. & Martin-Moreno, L. Faraday rotation due to excitation of magnetoplasmons in graphene microribbons. ACS Nano 7, 9780–9787 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z.B. conceived the idea, carried out the numerical simulations and wrote the first draft of manuscript text. K.F. and Z.A. discussed the proposed method and simulation results, as well as improved the manuscript presentation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ziaee Bideskan, M., Forooraghi, K. & Atlasbaf, Z. Method of lines for analysis of plane wave scattering by periodic arrays of magnetically-biased graphene strips. Sci Rep 11, 7588 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86882-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86882-z