Abstract

An InP substrate was directly bonded on a diamond heat spreader for efficient heat dissipation. The InP surface activated by oxygen plasma and the diamond surface cleaned with an NH3/H2O2 mixture were contacted under atmospheric conditions. Subsequently, the InP/diamond specimen was annealed at 250 °C to form direct bonding. The InP and diamond substrates formed atomic bonds with a shear strength of 9.3 MPa through an amorphous intermediate layer with a thickness of 3 nm. As advanced thermal management can be provided by typical surface cleaning processes followed by low-temperature annealing, the proposed bonding method would facilitate next-generation InP devices, such as transistors for high-frequency and high-power operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electronics industry has utilized indium phosphide (InP) to engineer advanced components. Because InP has high electron velocities, low contact resistances, and large heterojunction offsets in the InGaAs/InP system, InP-based electronic devices have been used in high-frequency applications with a maximum oscillation frequency of over 1 THz1,2,3,4. In addition, communications and networking specialists have been working on THz monolithic integrated circuits (TMIC) with InP high electron mobility transistors (HEMTs) and heterojunction bipolar transistors (HBTs)5,6,7. The direct bandgap of InP is useful in photonic device applications, such as InP laser/modulator/photodetector systems for next-generation optical communications8,9,10,11. Accompanying the demand for miniaturization and high-power operation12,13,14,15,16,17, the power density of these devices has drastically increased. Consequently, InP-based electronic devices suffer from heat dissipation problems due to the low thermal conductivity of 68 W/m/K (Si: 130 W/m/K)18,19,20.

For efficient heat dissipation, semiconductor researchers have developed an integration technique for devices on a diamond heat spreader, which has the highest thermal conductivity amongst solid materials (2200 W/m/K). For example, Ksenia Nosaeva et al. transferred a diamond heat-spreading layer on the InP HBT embedded in benzocyclobutene (BCB) resin21. Andreas Beling et al. integrated InP photodiodes on a diamond sub-mount by flip-chip bonding using metal bonding layers22,23. Direct bonding of the device and diamond is ideal to mitigate thermal resistance because the thermal conductivities of these bonding materials are an order of magnitude smaller than that of diamond. In particular, there have been intensive studies regarding the direct and indirect bonding of Ga-based materials (i.e., GaN24,25,26, GaAs27,28,29,30, and InGaP31) onto diamond substrates. However, studies on the direct bonding of InP and diamond substrates are scarce.

Our research group developed and reported a direct bonding method for semiconductor substrates (i.e., Si, Ga2O3) on a diamond heat spreader32,33,34,35,36. We found that OH groups were formed on a diamond surface treated with oxidizing solutions, such as H2SO4/H2O232 and NH3/H2O2 mixtures. Moreover, the OH-terminated diamond surface forms direct bonding with the OH-terminated semiconductor substrate by thermal dehydration at approximately 200 °C. The semiconductor substrates are typically OH-terminated using plasma activation37. While studies on the bonding of InP and diamond are scarce, optoelectronics scientists have developed multifunctional devices using direct bonding techniues38,39,40 and achieved the direct bonding of oxygen-plasma-activated InP lasers and Si waveguides41,42,43,44. Consequently, the InP surface activated by the oxygen plasma can be directly bonded with the OH-terminated diamond surface. To test this hypothesis, we proposed direct bonding of InP and diamond substrates and investigated nanostructures of the InP/diamond bonding interface, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Results

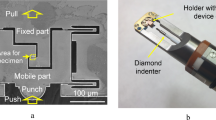

Figure 2 shows the diamond substrate bonded on the surface of the InP substrate. The bonding interface can be observed through the transparent diamond substrate. Diffused reflection due to the gaps between the substrates was observed where the surfaces were not bonded. While there were some bright spots, Fig. 2 indicates that three-quarters of the contacted area was successfully bonded. Voids with diameters of approximately 0.1 mm were formed due to particles on the substrate surface. The large unbonded regions at the corners of diamond substrates resulted from the convex diamond surface (see the supplement of34). If the environmental cleanliness and substrate flatness are improved, direct bonding will be formed at most of the contacted area. When a shear force of 9.3 MPa (84 N for 3 × 3 mm) was applied to the bonded diamond substrate, fracture at the bonding interface and cleavage along the InP (110) face were observed. In our previous studies, the bonding strength of Si/diamond36 and Ga2O3/diamond34 was fractured by the shear strength of 31.8 and 14 MPa, respectively. While the bonding interface of InP/diamond was low compared with them, the strength satisfies the die shear strength of MIL STD 883E.

Surfaces are required to be sufficiently smooth for direct bonding; the root mean square (RMS) roughness is preferably less than ~ 5 Å45. The diamond substrate used in this study had an atomically smooth surface with an RMS roughness of less than 3 Å, which was reported in our previous study36. The InP substrate surface was investigated using an atomic force microscope (AFM), as shown in Fig. 3. The RMS roughness of the InP substrate surface was initially 2.76 ± 0.3 Å. Thereafter, the surface roughness after the oxygen plasma irradiation was similar as the RMS roughness was 3.03 ± 0.3 Å; it was sufficiently smooth for bonding formation.

The surface chemical composition of the InP substrate was investigated through angle-resolved X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), as depicted in Fig. 4. The measurement depth depended on the take-off angle of the photoelectrons; the inelastic mean free path (IMFP) was calculated at approximately 1 and 4 nm for angles of 10.75° and 63.25°, respectively. Before plasma irradiation, the amounts of In–O and P–O bonds were relatively small, and organic contaminants were present on the surface. This indicated that the OH groups detected at the surface probably resulted from C–OH bonds, owing to contaminants. However, organic contaminants rarely existed, and In–O and P–O bonds were present on the plasma-activated InP surface. Thus, the OH bonds detected on the surface were possibly attributed to the In–OH, P–OH, or both groups generated on the InP substrate. Our previous study suggested that the diamond substrate cleaned with the NH3/H2O2 mixture was terminated with the C–OH groups36. Consequently, the OH groups on the InP and diamond substrates probably reacted with each other during the bonding process.

The nanostructure of the InP/diamond bonding interface was observed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM), as shown in Fig. 5. For the observation, the thickness of the InP substrate, bonded with diamond, was reduced to 10 µm by grinding. Subsequently, the ultra-thin TEM specimen was prepared using a focused ion beam (FIB). The incident angle of the electron beam was set parallel to the InP < 110 > direction. As shown in Fig. 5, the InP and diamond substrates formed atomic bonds without cracks or nanovoids. Moreover, an amorphous layer with a thickness of approximately 3 nm was observed at the bonding interface. Figure 6 depicted the compositional analysis obtained using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). The amorphous layer at the bonding interface is composed of In, P, O, and C. It is known that the InP/Si interface bonded using oxygen plasma is composed of In, P, and O44. The C atoms supposedly diffused into the oxide layer on the InP substrate formed by the oxygen plasma; the formation of the intermediate oxide layer is unavoidable in the case of the bonding under atmospheric conditions. It was assumed that the thermal conductivity of the intermediate layer was low but significantly thin compared with conventional approaches (e.g. 2–4-µm-thick metal layers21,22). Thus, it was supposed that the InP/diamond bonding technique would contribute to efficient heat dissipation from the InP electronic devices.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated the direct bonding of InP and diamond substrates to improve the heat dissipation of InP-based electronic devices. The InP substrate activated by oxygen plasma was contacted with the diamond substrate that was cleaned with a mixture of NH3, H2O2, and H2O under atmospheric conditions. Direct bonding was formed by annealing the contacted specimen at 250 °C. As both surfaces were atomically smooth after the pre-bonding treatments, the InP and diamond substrates successfully generated direct bonding with a shear strength of 9.3 MPa. The interfacial analysis revealed that they were bonded through an amorphous intermediate layer with a thickness of approximately 3 nm without cracks or nanovoids. The oxygen plasma treatment and cleaning with the NH3, H2O2, and H2O mixtures in the pre-bonding step are commonly applied substrate cleaning processes in the electronics industry. The subsequent bonding step can be realized using low-temperature annealing under atmospheric conditions. Because advanced thermal management can be achieved by simple procedures, this bonding technique would contribute to future InP devices with higher integration and power densities.

Method

In this study, commercially available InP and diamond substrates were directly bonded as received conditions, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Three-square-millimeter diamond (111) substrates with a thickness of 300 μm (from EDP Corp.) were bonded on a three-inch-diameter InP (100) wafer with a thickness of 500 μm (from Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd).

The diamond substrates were cleaned with a mixture of 10 mL of NH3 solution (28%), 10 mL of H2O2 solution (35%), and 50 mL of deionized water at 75 °C for 10 min. The diamond substrates were rinsed in deionized water and blown by nitrogen gas for drying. The InP substrates were activated with reactive ion etching equipment (QAP-1000, Bondtech). The plasma at a power of 200 W irradiated the InP surface for 30 s under an O2 pressure of 60 Pa and an O2 mass flow rate of 20 mL/min. In the contacting step, the activated InP substrate was placed on a Peltier cooler at 14 °C for approximately 30 s in our clean room (temperature: 23 °C, relative humidity: 40%), and then the diamond substrate was placed on the InP substrate. The cooling process developed condensed water molecules that are believed to promote hydrogen bond networks between the InP and diamond substrates. The contacted specimen was annealed at 250 °C for 24 h under a load of approximately 1 MPa.

The bonding quality was evaluated using a shear tester (4000Plus, Nordson DAGE). The surface roughness of the InP substrate was investigated using the AFM (L-trace, Hitachi). The surface chemical composition was studied using XPS (VG Theta Probe, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The nanostructure of the InP/diamond bonding interface was investigated using the TEM and EDX (JEM-ARM200F, JEOL).

References

Urteaga, M., Griffith, Z., Seo, M., Hacker, J. & Rodwell, M. J. W. InP HBT Technologies for THz Integrated Circuits. Proc. IEEE 105, 1051–1067 (2017).

Lai, R. et al. Sub 50 nm InP HEMT device with Fmax greater than 1 THz. In Technical Digest—International Electron Devices Meeting, IEDM 609–611 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2007.4419013.

Kim, D. H. et al. 50-nm E-mode in0.7Ga0.3As PHEMTs on 100-mm InP substrate with fmax > 1 THz. In Technical Digest—International Electron Devices Meeting, IEDM (2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2010.5703453.

Urteaga, M. et al. 130nm InP DHBTs with ft >0.52THz and fmax >1.1THz. In Device Research Conference—Conference Digest, DRC 281–282 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/DRC.2011.5994532.

Deal, W. et al. THz monolithic integrated circuits using InP high electron mobility transistors. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 1, 25–32 (2011).

Yoshida, W. et al. A terahertz capable 25 nm InP HEMT MMIC process. In CS MANTECH 2016—International Conference on Compound Semiconductor Manufacturing Technology 53–56 (2016).

Hacker, J. et al. THz MMICs based on InP HBT technology. In IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest 1126–1129 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/MWSYM.2010.5517225.

Ito, H. et al. High-speed and high-output InP-InGaAs unitraveling-carrier photodiodes. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 10, 709–727 (2004).

Lelarge, F. et al. Recent advances on InAs/InP quantum dash based semiconductor lasers and optical amplifiers operating at 1.55 μm. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 13, 111–123 (2007).

Smit, M., Williams, K. & Van Der Tol, J. Past, present, and future of InP-based photonic integration. APL Photonics 4, 050901 (2019).

Takeuchi, H. et al. Monolithic integrated coherent receiver on InP substrate. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 1, 398–400 (1989).

Wang, C., Huang, S. C., Huang, W. K. & Hsin, Y. An InP/InGaAs/InP DHBT with high power density at Ka-band. Solid State Electron. 52, 49–52 (2008).

Johnson, G. A. et al. InGaAs/InP submicron gate microwave power transistors for 20 GHz applications. 423–426 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1109/iciprm.1991.147403.

Biedenbender, M. D. et al. Submicron-gate Inp power Misfet’s with improved output power density at 18 and 20 Ghz. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 39, 1368–1375 (1991).

Doussiere, P., Shieh, C.-L., DeMars, S. & Dzurko, K. Very high power 1310 nm InP single mode distributed feed back laser diode with reduced linewidth. In Novel In-Plane Semiconductor Lasers VI (eds. Mermelstein, C. & Bour, D. P.) vol. 6485 64850G (SPIE, 2007).

Doussiere, P. High power lasers on InP substrates. In IEEE Photonic Society 24th Annual Meeting, PHO 2011 674–675 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/PHO.2011.6110729.

Ke, Q. et al. High power 1550 nm InGaAsP/InP lasers with optimized carrier injection efficiency. In ICOCN 2015—14th International Conference on Optical Communications and Networks, Proceedings (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICOCN.2015.7203677.

Pogoretskiy, V. et al. An integrated SOA-building block for an InP-membrane platform. In Optics InfoBase Conference Papers JW4A.1 (OSA - The Optical Society, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1364/IPRSN.2017.JW4A.1.

Lindberg, H., Strassner, M., Gerster, E., Bengtsson, J. & Larsson, A. Thermal management of optically pumped long-wavelength InP-based semiconductor disk lasers. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 11, 1126–1134 (2005).

Sokół, A. K. & Sarzała, R. P. Comparative analysis of thermal problems in GaAs- and InP-based 1.3-μm VECSELs. Opt. Appl. 43, 325–341 (2013).

Nosaeva, K. et al. Improved thermal management of InP transistors in transferred-substrate technology with diamond heat-spreading layer. Electron. Lett. 51, 1010–1012 (2015).

Beling, A. et al. High-power photodiodes for analog applications. IEICE Trans. Electron. E98.C, 764–768 (2015).

Xie, X., Zhou, Q., Li, K., Beling, A. & Campbell, J. 1.8 watt RF power and 60% power conversion efficiency based on photodiode flip-chip-bonded on diamond. In Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics Europe—Technical Digest JTh5B.9 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2014). https://doi.org/10.1364/cleo_at.2014.jth5b.9.

Liang, J. et al. Stability of diamond/Si bonding interface during device fabrication process. Appl. Phys. Express 12, 016501 (2018).

Cheng, Z., Mu, F., Yates, L., Suga, T. & Graham, S. Interfacial thermal conductance across room-temperature-bonded GaN/diamond interfaces for GaN-on-diamond devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 8376–8384 (2020).

Mu, F., He, R. & Suga, T. Room temperature GaN-diamond bonding for high-power GaN-on-diamond devices. Scr. Mater. 150, 148–151 (2018).

Liang, J. et al. Fabrication of high-quality GaAs/diamond heterointerface for thermal management applications. Diam. Relat. Mater. 111, 108207 (2020).

Sugino, T., Itagaki, T. & Shirafuji, J. Formation of pn junctions by bonding of GaAs layer onto diamond. Diam. Relat. Mater. 5, 714–717 (1996).

Sugino, T., Itagaki, T. & Shirafuji, J. p-diamond/n-GaAs junctions formed by direct bonding. Electron. Lett. 32, 71 (1996).

Cho, S. J. et al. Fabrication of AlGaAs/GaAs/diamond heterojunctions for diamond-collector HBTs articles you may be interested in. AIP Adv. 10, 125226 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. Room temperature direct bonding of diamond and InGaP in atmospheric air. Funct. Diam. 1, 110–116 (2021).

Matsumae, T., Kurashima, Y., Umezawa, H. & Takagi, H. Hydrophilic direct bonding of diamond (111) substrate using treatment with H2SO4/H2O2. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 59, SBBA01 (2020).

Matsumae, T., Kurashima, Y., Umezawa, H. & Takagi, H. Hydrophilic low-temperature direct bonding of diamond and Si substrates under atmospheric conditions. Scr. Mater. 175, 24–28 (2020).

Matsumae, T. et al. Low-temperature direct bonding of β -Ga2O3 and diamond substrates under atmospheric conditions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 141602–141611 (2020).

Matsumae, T., Kurashima, Y., Takagi, H., Umezawa, H. & Higurashi, E. Low-temperature direct bonding of diamond (100) substrate on Si wafer under atmospheric conditions. Scr. Mater. 191, 52–55 (2021).

Fukumoto, S. et al. Heterogeneous direct bonding of diamond and semiconductor substrates using NH3/H2O2cleaning. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 201601 (2020).

Suni, T., Henttinen, K., Suni, I. & Mäkinen, J. Effects of Plasma Activation on Hydrophilic Bonding of Si and SiO2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 149, G348 (2002).

Takigawa, R. & Asano, T. Thin-film lithium niobate-on-insulator waveguides fabricated on silicon wafer by room-temperature bonding method with silicon nanoadhesive layer. Opt. Express 26, 24413 (2018).

Takigawa, R., Kawano, H., Ikenoue, H. & Asano, T. Investigation of the interface between LiNbO3 and Si wafers bonded by laser irradiation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 56, 088002 (2017).

Kawano, H., Takigawa, R., Ikenoue, H. & Asano, T. Bonding of lithium niobate to silicon in ambient air using laser irradiation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 55, 110304 (2016).

Fang, A. W. et al. A continuous-wave hybrid AlGaInAs—silicon evanescent laser. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 18, 1143–1145 (2006).

Park, H., Fang, A. W., Kodama, S. & Bowers, J. E. Hybrid silicon evanescent laser fabricated with a silicon waveguide and III-V offset quantum wells. Opt. Express 13, 9460 (2005).

Pasquariello, D. & Hjort, K. Plasma-assisted InP-to-Si low temperature wafer bonding. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 8, 118–131 (2002).

Itawi, A., Pantzas, K., Sagnes, I., Patriarche, G. & Talneau, A. Void-free direct bonding of InP to Si: advantages of low H-content and ozone activation. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B Nanotechnol. Microelectron. Mater. Process. Meas. Phenom. 32, 021201 (2014).

Takagi, H., Maeda, R., Chung, T., Hosoda, N. & Suga, T. Effect of surface roughness on room-temperature wafer bonding by Ar beam surface activation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 37, 4197–4203 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18K18863.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. conceived, conducted and analysed the experiments, and prepared the original manuscript. R.T. conceived the experiments. Y. K., H. T., and E. H. reviewed the manuscript. T.M. and R.T. contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsumae, T., Takigawa, R., Kurashima, Y. et al. Low-temperature direct bonding of InP and diamond substrates under atmospheric conditions. Sci Rep 11, 11109 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90634-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90634-4

This article is cited by

-

Thermal management materials for 3D-stacked integrated circuits

Nature Reviews Electrical Engineering (2025)