Abstract

We report strong second-harmonic generation (SHG) from 2H polytype of multilayer Tin diselenide (SnSe2) for fundamental excitation close to the indirect band-edge in the absence of excitonic resonances. Comparison of SHG and Raman spectra from exfoliated SnSe2 flakes of different polytypes shows strong (negligible) SHG and Raman Eg mode at 109 cm−1 (119 cm−1), consistent with 2H (1T) polytypes. The difference between the A1g–Eg Raman peak positions is found to exhibit significant thickness dependent for the 1T form, which is found to be absent for the 2H form. The observed thickness dependence of SHG with rapid oscillations in signal strength for small changes in flake thickness are in good agreement with a nonlinear wave propagation model considering nonlinear polarization with alternating sign from each monolayer. The nonlinear optical susceptibility extracted from SHG signal comparison with standard quartz samples for 1040 nm excitation is found to be more than 4-times higher than that at 1550 nm. This enhanced nonlinear response at 1040 nm is attributed to the enhanced nonlinear optical response for fundamental excitation close to the indirect band-edge. We also study SHG from heterostructures of monolayer MoS2/multilayer SnSe2 which allows us to unambiguously compare the nonlinear optical response of SnSe2 with MoS2. We find the SHG signal and any interference effect in the overlap region to be dominated by the SnSe2 layer for the excitation wavelengths considered. The comparison of SHG from SnSe2 and MoS2 underscores that the choice of the 2D material for a particular nonlinear optical application is contextual on the wavelength range of interest and its optical properties at those wavelengths. The present works further highlights the usefulness of near band-edge enhancement of nonlinear processes in emerging 2D materials towards realizing useful nanophotonic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two dimensional (2D) materials with their novel opto-electronic properties continue to garner a lot of interest in the field of nonlinear optics1,2. Monolayer and multilayer 2D materials exhibit strong nonlinear optical response owing to their highly ordered crystalline structure, interesting layer number, polarization dependence3, and offer the possibility of incorporating electrical tunability4,5. These properties have led to 2D materials being proposed for use as ultra-thin active photonic devices for wavelength conversion, saturable absorption, optical limiting, optical modulation, parametric down-conversion etc.1 Second-harmonic generation (SHG) is one such nonlinear wavelength-conversion process in which high intensity laser illumination at the fundamental excitation is up-converted to twice the input frequency. Many of the transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) exhibit extraordinary SHG response due to their layer number dependent non-centrosymmetry3,6,7. The nonlinear optical response from TMDCs are strongly enhanced near their excitonic resonances4,5. The nonlinear optical response is also expected to be enhanced close to direct or indirect band-edges due to the fundamental excitation being close to real states with increased density-of-states near the band-edge8,9. Such band-edge enhancement of nonlinear optical processes has been reported previously in bulk semiconductors10,11, but not reported for 2D materials, too the best of our knowledge. In this paper we report strong SHG from 2H polytype multilayer Tin diselenide (SnSe2) for fundamental excitation in the vicinity of the indirect band-edge.

SnSe2 is a group IV-VI metal dichalcogenide with a hexagonal lattice structure12. Layered SnSe2 is known to exist in both 1T and 2H polytype forms with D3d and D3h symmetry respectively13,14. The crystals with D3d and D3h symmetry exhibits layer number independent centrosymmetry, and odd-layer non-centrosymmetry respectively. The indirect and direct energy bandgaps of SnSe2 are in the range of 1.07–1.59 eV and 1.84–2.04 eV respectively, depending on the layer number9. Multi-layer SnSe2 with layer number greater than ten exhibits indirect bandgap close to the bulk form (~ 1.07 eV)8. There are no excitonic resonance features observed in either monolayer or multilayer form, leading to band-to-band transitions being the dominant optical process. In the context of nonlinear optical studies, saturable absorption using multilayer SnSe2 for nanosecond and sub-picosecond optical pulse generation has been reported previously15,16,17. We have previously reported multi-photon photoluminescence enhancement in monolayer-MoS2/multilayer-SnSe2 heterostructures due to a resonant energy transfer mechanism between the strongly absorbing multilayer SnSe2 and the light emitting monolayer MoS218. We have also studied thickness dependent forward and backward generated third-harmonic generation from multilayer SnSe219.

For studying the nonlinear optical properties of 2D materials, nonlinear optical microscopy has been a particularly useful tool. This has been applied to identify crystal structure20, grain boundaries21, sample inhomogeneity22, and twist-angle between artificial stacked layers23. In the present work, we make use of SHG microscopy to acquire spatio-spectral maps of multilayer SnSe2 flakes and its heterostructures to determine the thickness, polarization, and excitation wavelength dependence of the SHG signal. First, we compare the SHG signal strength and Raman spectra from samples of different polytypes of SnSe2 and observe strong (negligible) SHG combined with Eg Raman mode observed at 109 cm−1 (119 cm−1). These observations correlate well with the properties of 2H and 1T polytypes of SnSe2. The difference between the A1g–Eg Raman peak positions is found to exhibit strong thickness dependent for the 1T form, which is absent for the 2H form. We observe rapid oscillations in SHG signal with small changes in flake thickness combined with a gradual decrease in the SHG signal with increased thickness. The thickness dependent SHG agrees well with a nonlinear-wave propagation model considering layered medium with alternating signs for the nonlinear optical susceptibility of the individual monolayers. Comparative SHG measurements with quartz is used to extract the nonlinear optical susceptibility. The second-order nonlinear optical susceptibility at 1040 nm (1.19 eV) excitation is found to be more than 4-times higher than that at 1550 nm (0.8 eV) excitation for SnSe2, which has an indirect band gap in the range of 1.07–1.59 eV. This is attributed to the enhancement of SHG for fundamental excitation in close vicinity of the indirect band-edge. SHG images of heterostructures of monolayer MoS2/ multilayer SnSe2 are used to compare the SHG signal strengths and understand SHG interference in the overlap region. The SHG signal from the multilayer SnSe2 considered here is ~ 34 times stronger than monolayer MoS2 for 1040 nm excitation. This is observed despite considering monolayer MoS2 having a direct bandgap at 1.9 eV18, which is expected to give the strongest SHG signal for layered MoS2. The present work underscores the usefulness of near band-edge enhancement of nonlinear optical processes in emerging 2D materials, such as SnSe2 with potential applications in realizing ultra-thin nonlinear optical devices.

Results and discussion

Comparison between two common polytypes of SnSe2

First, we perform SHG measurements and Raman spectroscopy on SnSe2 flakes (12 samples in total) from two different sources, as described in the “Methods” section below. We observe clear clustering of the samples into two groups based on the SHG signal strength, which is found to correlate well with the observed Raman peak positions and its thickness dependence. This clustering is found to be consistent with the 1T and 2H polytypes of SnSe2. Figure 1 shows a representative comparison of the optical, atomic force microscopy (AFM), SHG images and Raman spectroscopy measurement acquired for multilayer SnSe2 with the two distinct polytypes. The optical (Fig. 1a, b) and AFM (Fig. 1c, d) images of the two samples show very similar color contrast and thickness profiles. The SHG images (Fig. 1e, f) however show signal strengths which are different by almost an order of magnitude. The observed difference in SHG signal strength between the two samples is consistent with the centrosymmetric 1T polytype exhibiting negligible SHG in comparison to the non-centrosymmetric 2H polytype exhibiting strong SHG for odd number of layers. This observation is further corroborated by Raman spectroscopy measurements. Raman scattering is known to be sensitive to material phase and has been used for identifying different polytypes in TMDCs24,25. Raman spectra acquired for both thin and thick regions of the two samples are shown in Fig. 1g. The in-plane (Eg) Raman mode for the two samples are located at ~ 109 cm−1 and ~ 119 cm−1 respectively. This is consistent with previous reports of Raman spectra from 2H and 1T polytypes of SnSe214,26. The out-of-plane (A1g) Raman mode is obtained at ~ 186 cm−1 for both polytypes with slight blueshift with increasing thickness. The thickness dependence of the Raman peak separation between the A1g and Eg modes, shown in Fig. 1h also exhibits clear difference between the two samples. The error bar in the AFM thickness measurement of each data point considers the variation of thickness over an area of 0.4 × 0.4 µm2 with a pixel resolution of 80 nm. For the 1T polytype, the A1g–Eg peak separation is found to decrease with increasing layer thickness (blue shaded area in Fig. 1h). This is consistent with the previous report of Raman spectroscopy on SnSe2 nanoflakes14. The 2H polytype however shows negligible thickness dependence of A1g–Eg separation (orange shaded area in Fig. 1h). This observation for the 2H polytype has not been reported previously, to the best of our knowledge.

Optical images of: (a) 1T, (b) 2H polytype of SnSe2. AFM images of: (c) 1T, (d) 2H polytypes of SnSe2. SHG images of: (e) 1T, (f) 2H polytypes of SnSe2. Scale bar for all images is 5 μm (g) Raman spectra of 1T (blue solid curves) and 2H (orange solid curves) sample, the dashed black line indicates the Raman peak positions of the Eg and A1g Raman modes. (h) Thickness dependent A1g–Eg Raman peak separation for SnSe2, 1T (blue solid circles) and 2H (orange solid circles). (Created in MATLAB v9.6, R2019a, https://in.mathworks.com/).

Recent reports have also shown that SnSe2 can transform to Tin monoselenide (SnSe) due to thermal annealing27. SnSe is known to also exhibit strong SHG28. The observed Raman peak positions obtained from the sample after the SHG studies are consistent with that of SnSe2 and shows that the sample does not undergo stoichiometric conversion to SnSe. In the rest of the experimental study presented in this paper, we focus only on 2H SnSe2 due to the strong SHG signals obtained for this polytype.

Thickness dependent SHG from 2H SnSe2

A summary of images obtained from four different multilayer 2H SnSe2 samples (labeled sample 1, 2, 3 and 4) is shown in Fig. 2. The sample preparation technique is described in the “Methods” section. Optical images obtained using reflectance microscopy are shown in Fig. 2a–d with the observed color contrast corresponding to the thickness dependence of the reflected light. AFM images of the same samples are shown in Fig. 2e–h. From AFM measurements, the thickness of the samples are in the range of 5–40 nm. We could not obtain monolayer or few layer SnSe2 samples in this study. SHG microscopy images of the samples are shown in Fig. 2i–l. The nonlinear optical microscopy system used for acquiring the SHG images is described in “Methods” section. The SHG images shown are acquired with fundamental excitation at 1040 nm, linearly polarized and parallel to the armchair axis of the SnSe2 flake (the armchair axis is indicated by the double-sided arrow in the SHG images). Qualitative inspection of the SHG images shows that the SHG signal is found to be highest for the thinner regions. We also observe rapid changes in the SHG signal for small changes in the flake thickness. This is clearly seen from the line scans included as insets in the SHG and AFM images. Such rapid variation in the SHG signal strength points to strong layer number dependence of the nonlinear signal. Figure 3a shows the quadratic functional form of SHG signal as a function of fundamental excitation power for sample 1. The slope of the log–log power dependent SHG signal plot is obtained as 2.1 ± 0.02, confirming the second-order nature of the generated nonlinear optical signal. Figure 3b shows the polarization dependent SHG from sample 1 obtained by rotating the sample from 0° to 360° for linearly polarized fundamental excitation with parallel and perpendicular analyzer orientations relative to the incident light polarization. The six-fold symmetry of the SHG signal in the polar plot can be attributed to the underlying hexagonal lattice system of 2H SnSe2 with D3h symmetry3.

Summary of images acquired for four different 2H SnSe2 samples using different imaging modalities. (a–d) optical reflectance images, (e–h) AFM image and (i–l) SHG image with incident light polarized along the arm-chair axis. Each line-scan shown in the inset of AFM and SHG image are along the white dashed line marked in the images with arrow points the direction of the line-scan. Scale bar shown in all images is 5 μm. The double-headed arrows shown in the SHG Images correspond to the incident polarization direction. (Created in MATLAB v9.6, R2019a, https://in.mathworks.com/).

(a) Power dependence of SHG measurement. Filled circles correspond to experimental data and solid line corresponds to the linear fit of the log–log plot. The extracted slope is shown in the legend. (b) Polarization-dependent SHG measurement as a function of incident polarization direction. \({\phi }_{o}\) refers to the initial offset between the armchair direction and the laboratory axes. Blue and orange filled circles correspond to experimental data for parallel and perpendicular polarization relative to the analyzer orientation. Solid curves correspond to theoretical fit to the experimental data points. (Created in MATLAB v9.6, R2019a, https://in.mathworks.com/).

To understand the observed thickness dependence of SHG for 2H polytype of SnSe2 we utilize a nonlinear wave propagation model across the layered medium. The nonlinear wave propagation model implemented in COMSOL Multiphysics software29 is described in the “Methods” section. SnSe2 possess a large refractive index (close to 3)12,30 at the wavelengths of interest in this work, resulting in the SHG process being strongly influenced by Fabry–Perot effects in addition to the expected dependence on phase mismatch and optical absorption19,31,32. The nonlinear wave-propagation model inherently considers these effects when solving for the field profiles and detected nonlinear signal. Figure 4a, b show the schematic cross-sectional views of the layered material above a silicon dioxide layer on a silicon substrate for the two different nonlinear optical susceptibility models considered here. Figure 4a shows the bulk nonlinear optical susceptibility model with the SnSe2 layer having uniform second-order nonlinear optical susceptibility of \({\chi }_{b}^{\left(2\right)}\) across its thickness. Figure 4b shows the alternating layer model consisting of each monolayer of SnSe2 with alternating signs for the nonlinear optical susceptibility. This closely models the D3h crystal symmetry with alternating signs of nonlinear polarization from adjacent monolayers3,33. The sheet nonlinear optical susceptibility, \({\chi }_{s}^{\left(2\right)}\) for the monolayer is given as: \(\frac{{\chi }_{b}^{\left(2\right)}}{{L}_{eff}}\), with monolayer thickness Leff = 0.65 nm. Figure 4c, d shows the simulated field profiles and nonlinear polarization obtained by solving for the nonlinear wave propagation equation for the two different models for a fixed SnSe2 layer thickness of ~ 8.45 nm (13-layers). Both the fundamental and SHG fields are shown with each region demarcated by vertical dotted lines and appropriate labels. The fundamental fields, as depicted by the solid blue line remain identical for both the models as this depends only on the linear optical properties of the 2D material. The solid orange lines represent the absolute value of the SHG nonlinear polarization. The SHG field shown by the dashed blue curve is however found to be lower for the alternating layer model (shown in Fig. 4d) when compared to the bulk model (shown in Fig. 4c). This is expected due to the approximate cancellation of the second-harmonic sheet dipoles resulting in SHG signal from effectively a single layer in the case of odd number of SnSe2 layers. In contrast, for the bulk model the SHG field is found to be significantly higher across the entire SnSe2 layer. Figure 4e, f show a comparison of the simulated SHG obtained at the detector plane with the experimentally obtained thickness-dependent SHG signal. The experimentally obtained thickness dependent SHG data from all the four samples shown in Fig. 2 are combined in this plot. The rapid oscillations in SHG signal combined with the gradual decrease with thickness are found to be in very good agreement with the alternating sign nonlinear susceptibility model (shown in Fig. 4f). In contrast, the simulated SHG signal for the bulk model peaks for a film thickness of ~ 10–15 nm and decreases slowly under the combined influence of phase mismatch and optical absorption (shown in Fig. 4e). This thickness-dependent SHG for the bulk model does not agree with the experimental data. The observed rapid variation in SHG signal for small changes in flake thickness, the good agreement with the alternating sign nonlinear susceptibility model, the measured six-fold polarization dependence of the SHG signal and observed spectral position of Eg Raman mode provides strong evidence for the observation of SHG from the 2H polytype of SnSe2 in this study with D3h (D3d) symmetry for odd (even) numbered layer.

Comparison of thickness-dependent SHG experiments with nonlinear wave propagation simulations for multilayer SnSe2. Schematic cross-section view of the: (a) bulk nonlinearity model, and (b) alternating nonlinear layer model. (c, d) Simulation results showing the fundamental field profiles (solid blue curves), SHG field profiles (dashed blue curves) and nonlinear polarization (solid red curves). (e, f) Comparison of the experimental (solid colored circles) and simulated (solid blue curves) SHG signals for the two different nonlinearity models considered here. A zoomed-in view of this plot is shown as an inset. (Created in MATLAB v9.6, R2019a, https://in.mathworks.com/).

We also consider the possibility of interfacial break in symmetry contributing to the observed SHG signal from SnSe2, as observed in other centrosymmetric materials34,35. For pristine, dangling bond free surfaces achievable with mechanical exfoliated Van der Waal layered materials, the interfacial break in symmetry is in general not observed36. Furthermore, the interfacial model cannot explain the observed rapid oscillations in the SHG signal for small thickness variations as the SHG signal would exist irrespective of the layer number. SHG emission is also observed from distorted 1-T′ layered materials, such as Rhenium disulfide (ReS2) which otherwise exhibit centrosymmetry in the absence of lattice distortion37. There is however anisotropic polarization dependent SHG observed in the SHG emission due to lattice distortions. Given the symmetric sixfold polar plots obtained for SnSe2 as shown in Fig. 3b, lattice distortion can clearly be ruled out as the cause of SHG signal.

Extracting second order nonlinear optical susceptibility of 2H SnSe2

Next, the wavelength dependence of the SHG signal and calculating the second order nonlinear susceptibility from SnSe2 are investigated. Figure 5a, b shows the SHG images acquired from sample 3 at 1040 nm and 1550 nm fundamental excitation wavelengths. The SHG signal obtained for 1040 nm excitation is found to be ~ 175.5 times higher than that for 1550 nm excitation, when scaled to the same intensity levels and detector response. This enhanced SHG signal strength is attributed to the stronger nonlinear optical response for 1040 nm fundamental excitation wavelength. We also extract the second-order nonlinear susceptibility, χ(2) at these two wavelengths by comparing the SHG signal from SnSe2 with a standard Z-cut quartz window. The procedure followed to extract the nonlinear optical susceptibility is described in the “Methods” section. Figure 5c, d shows a comparison of the SHG signals and extracted χ(2) for the two excitation wavelengths and fixed SnSe2 layer thickness of ~ 7.1 nm (11-layers). The SHG signal from quartz is found to be ~ 5.8 and ~ 32 times higher than that of SnSe2 for 1040 nm and 1550 nm excitation respectively. Nonetheless, the χ(2) values are found to be 32 and 7.5 times higher for SnSe2 when compared to quartz. In comparison to quartz, the nonlinear optical susceptibility for SnSe2 is higher even though the SHG signal strength is weaker due to the reduced interaction length over which SHG is generated for SnSe2. We also extend the χ(2) coefficient calculation for varying SnSe2 thickness for the two excitation wavelengths in Fig. 5e to test the robustness of the χ(2) calculation procedure. The observed variations in the χ(2) value are mainly attributed to the error in AFM measurements leading to inaccuracies in the SnSe2 layer thickness considered in the calculation. The average χ(2) values extracted for SnSe2 are 19 ± 2 pm/V and 4.5 ± 0.9 pm/V for 1040 nm and 1550 nm excitations respectively. The SHG signal strength and second-order nonlinear optical susceptibility for 1040 nm excitation are higher than that at 1550 nm excitation. This is attributed to the near band-edge excitation at 1040 nm, which is expected to enhance the nonlinear optical response from SnSe2, in similar lines to previous observations in direct and in-direct bandgap semiconductors10,11. The use of a fixed center wavelength fiber laser at 1040 nm in this study prevented the tuning of the excitation wavelength around the indirect band-edge of SnSe2 to obtain the nonlinear optical susceptibility spectrum.

Wavelength dependent SHG from multilayer SnSe2. SHG images acquired at (a) 1040 nm, and (b) 1550 nm excitation wavelengths. The scale bar corresponds to 5 μm. Bar-charts comparing SHG signal (blue) and extracted nonlinear optical susceptibility (orange) for Quartz and SnSe2 for (c) 1040 nm, and (d) 1550 nm excitation wavelengths. (e) Thickness dependent nonlinear optical susceptibility for 1040 nm (orange) and 1550 nm (blue) excitation wavelength. The dashed lines indicate the average value. (Created in MATLAB v9.6, R2019a, https://in.mathworks.com/).

SHG from monolayer-MoS2/ multilayer-SnSe2 heterostructure

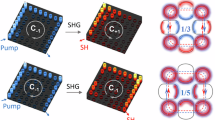

The nonlinear optical susceptibility values extracted here are comparable to previously reported values from other popular TMDC based layered materials1,3. However, large variations are observed in the nonlinear optical signal strength and susceptibility values reported previously1. Here, we perform SHG microscopy and polarization studies on artificially stacked heterostructures of monolayer MoS2 transferred on multilayer SnSe2, with the objective of comparing the relative SHG signal strength of SnSe2 with MoS2 in one sample and also understand SHG interference effects38 in the overlap region. The method followed for preparing the heterostructure is discussed in the “Methods” section. Figure 6a, b shows the optical and AFM images of the MoS2/SnSe2 heterostructures studied here. The green and white boundaries in Fig. 6a delineate the MoS2 and SnSe2 layers respectively. Figure 6c, d show the SHG images of the heterostructure acquired for 1040 nm and 1550 nm excitation wavelength. The SHG signal from SnSe2 is found to be ~ 34 and 3.4 times higher than MoS2 for 1040 nm and 1550 nm excitation wavelengths respectively. This is observed despite considering monolayer MoS2, which is expected to result in the highest SHG signal for layered MoS23. The large SHG signal observed for multilayer SnSe2 when compared to MoS2 for 1040 nm excitation is attributed to the near-indirect band-edge excitation of SnSe2, with both fundamental (1040 nm/1.19 eV) and second harmonic wavelength (520 nm/2.38 eV) lies much far away from the excitonic resonance features in the case of MoS2 monolayer with a direct band gap at 1.9 eV. We also perform polarization dependent SHG studies on the MoS2/SnSe2 heterostructures to obtain the orientation dependence of SHG signal from individual layers. Figure 6e, f shows polar plots corresponding to the polarization dependence of SHG signal with the sample rotated from 0° to 180° with the incident light linearly polarized and aligned parallel to the analyzer direction. The polar plots show the SHG signal obtained from SnSe2, MoS2, and the overlap regions. The polar plots show the expected six-fold symmetric pattern when considering the full 0°–360° polarization angle. This agrees with the expected SHG polarization dependence for material with D3h symmetry, such as SnSe2 and MoS2. The SHG images at 1040 nm and 1550 nm excitation wavelength are rotated by 60° and are equivalent in terms of the armchair orientation relative to the incident polarization direction due to the six-fold symmetry. The arm-chair axes of MoS2 and SnSe2 layers are found to be aligned very close to each other during the layer transfer, as evident from the overlap of the six-lobe polar plots for the individual layers. The SHG signal from the overlap junction region is determined by the interference of the SHG generated from the individual layers and the relative phase between the individual second-order nonlinear polarization. The SHG signal from MoS2 being weaker than SnSe2 at 1040 nm excitation results in weak interference between the SHG generated between the two layers. The overlap junction region is found to show reduced SHG signal for 1040 nm excitation due to the absorption of the generated SHG at 520 nm by the MoS2 overlayer. In contrast, the overlap junction region shows enhanced SHG signal for 1550 nm excitation, which is attributed to stronger interference due to comparable SHG signals for the individual layers and negligible reabsorption in the MoS2 layer. Previous reports have shown enhanced photoluminescence18 and Raman scattering39 from the overlap region of MoS2/SnSe2 heterostructures. This is attributed to a resonant energy transfer mechanism between the SnSe2 layer and the MoS2 layer. In the context of parametric nonlinear optical processes such as SHG, we do not expect to observe enhancement in the overlap region due to resonant energy transfer processes. This is due to the instantaneous nature of the parametric nonlinear process such as SHG, resulting in negligible enhancement due to the more slower energy transfer mechanisms.

SHG from monolayer (1L) MoS2/multilayer SnSe2 heterostructure. (a) Optical brightfield image of the heterostructure with green and white dashed boundaries delineate the boundary of MoS2 and SnSe2 respectively. (b) AFM image of the heterostructure. SHG images acquired for (c) 1040 nm, and (d) 1550 nm excitation wavelengths. The scale bar in the images corresponds to 5 μm. Polarization dependent SHG polar plots shown for (e) 1040 nm and (f) 1550 nm excitation wavelengths. The polar plots corresponding to MoS2 region (blue curve), SnSe2 region (orange curve) and overlap junction region (green curves) are shown. The experimental data and six-fold fit are shown by filled circles and solid curves respectively. (Created in MATLAB v9.6, R2019a, https://in.mathworks.com/).

Conclusions

We report, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, SHG from multilayer 2H polytype of SnSe2 and observe strong second-order nonlinear optical response for fundamental excitation in the vicinity of the indirect band-edge. Comparison between the SHG and Raman spectra for two different polytypes of SnSe2 shows strong(negligible) SHG combined with characteristic Eg Raman modes at 109 cm−1(119 cm−1) for the 2H(1T) polytypes. The Raman peak position difference between the A1g–Eg modes also shows clear thickness dependence for the 1T form, which is absent for the 2H form. We observe rapid variations in the SHG signal for small changes in flake thickness and characteristic six-fold symmetric polarization dependence of SHG. The thickness dependence of SHG signal is found to be in good agreement with a nonlinear wave propagation model considering multiple monolayers of alternating signs for the nonlinear susceptibility. The nonlinear optical susceptibility of SnSe2 is found to be more than four times higher for 1040 nm when compared to 1550 nm excitation. This is attributed to the strong nonlinear optical response close to the indirect band-edge of SnSe2. We also acquire SHG images from monolayer MoS2/ multilayer SnSe2 sample to unambiguously compare the relative SHG signal strengths and understand the interference effect in the overlap region. We find that the SHG signal and hence the interference signal in the overlap region is dominated by the SnSe2 layer for the wavelengths under consideration. The present work shows that emerging 2D materials such as SnSe2 exhibit strong nonlinear optical response close to its band-edge even in the absence of excitonic resonances with nonlinear optical properties comparable to other popular 2D materials. The near-band edge enhancement of nonlinear optical response from such emerging 2D materials can potentially open the spectral range over which 2D materials can find applications as ultrathin nonlinear photonic devices. There is interest in realizing active photonic functionalities using 2D materials away from strong resonance features40,41. Having quantitative knowledge of the nonlinear optical properties close to and far away from band-edge or resonances as presented here is essential in evaluating the usefulness of these materials.

Methods

Sample preparation and characterization

Multilayer SnSe2 (from 2D Semiconductor, USA and HQ graphene, Netherlands) samples are prepared using dry transfer method in which Scotch tape is used to exfoliate the flakes of SnSe2 onto the Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate. Suitable flake with varying thickness is identified and transferred by stamping the PDMS onto silicon substrate with 285 nm silicon dioxide layer. MoS2/SnSe2 heterostructure samples are prepared by first identifying uniform thickness SnSe2 layer with thickness of ~ 8 nm. Monolayer MoS2 is then transferred on top of the SnSe2 layer, partly covering the SnSe2 region. The final sample consists of monolayer MoS2/ multilayer SnSe2 junction region along with separate regions of monolayer-MoS2 and SnSe2 only for SHG studies. Photoluminescence (PL) measurement performed on the MoS2 layer showed PL peak position at ~ 1.9 eV, confirming monolayer MoS2 (not shown here)18.

Optical reflectance microscopy of the transferred flakes is performed using an inverted microscope, Olympus IX73. AFM imaging is performed using Park AFM NX20 system in non-contact mode. Raman spectroscopy is performed using Renishaw Raman spectrometer. All measurements are taken over a scanning range of 100–500 cm−1 with 532 nm excitation focused using a 100 × objective lens. The incident optical power at the sample is kept as low as 80 μW to avoid any heating effects on the sample.

Nonlinear microscopy system

For the SHG measurement on the 2D materials, we use a conventional nonlinear optical microscopy setup19. This system consists of a femtosecond pump laser source (Fidelity HP) at 1040 nm wavelength with pulse width of 140 fs, and repetition rate of 80 MHz. The power and the polarization of the input laser source are controlled using half-wave plate and polarizer. A portion of the pump laser source is used to pump an optical parametric oscillator (Levante-IR) tuned to generate signal at 1550 nm wavelength with pulse width of ~ 200 fs pulse width and repetition rate of 80 MHz. The SnSe2 sample is fixed at the center of the rotational mount placed over an XY motorized stage on an Olympus inverted microscope. The input laser source is focused on the sample using a 20x/0.75 NA Olympus objective. The average input power on the sample at 1040 nm and 1550 nm excitation wavelength are measured to be 3.6 mW and 8.6 mW respectively. The measured illumination at the back aperture of the objective is around 42% and 100% for 1040 nm and 1550 nm excitation wavelength leads to a spot size of 3.64 µm and 2.52 µm, corresponding to a peak input optical intensity of 3.08 GW/cm2 and 10.74 GW/cm2, respectively. The backward emitted SHG signal is collected using the same objective and separated from the excitation laser using dichroic beam-splitter. The SHG signal is further spectrally isolated using a series of bandpass (520 ± 20 nm for 1040 nm excitation and 785 ± 40 nm for 1550 nm excitation) and short pass filters (890 nm cut-off) and detected using a photomultiplier tube (PMT). The set of bandpass and short-pass filters ensured effective rejection of the fundamental excitation with ~ 150 dB extinction, thus ensuring detection of only the SHG signal. SHG images are obtained by scanning the incident laser beam using a pair of galvo-scanning mirrors and mapping the PMT signal. The use of a fixed fiber laser source at 1040 nm center wavelength prevented scanning the fundamental excitation wavelength. For SHG polarization studies, the 2D material sample mounted on a rotary mount is rotated from 0° to 360° in 5° steps. The parallel and perpendicular oriented SHG signals are detected by using an analyzer in front of the PMT. The parallel and perpendicular SHG components refer to the analyzer oriented parallel and perpendicular to the incident linear polarization directions respectively.

Nonlinear wave propagation simulation

The evolution of the nonlinear optical signal in the SnSe2 samples and its radiation to the far-field is described using the inhomogeneous wave equation under the slowly varying amplitude approximation. This nonlinear wave propagation equation for the second harmonic field (\({\mathrm{E}}_{2}\)) can be expressed as8:

Here, the second order nonlinear polarization at the SHG wavelength, \({{\mathrm{P}}_{2}}^{\left(2\right)}\) is given as: \({{\mathrm{P}}_{2\mathrm{i}}}^{\left(2\right)}={\upepsilon }_{\mathrm{o}}{\upchi }_{\mathrm{ijk}}^{(2)} {\mathrm{E}}_{1\mathrm{j}}{\mathrm{E}}_{1\mathrm{k}}\) is the source term for the SHG process which depends on the mixing of the fundamental input electric field components (\({E}_{1j}{E}_{1k}\)). The nonzero elements, \({\upchi }_{\mathrm{ijk}}^{(2)}\) for a crystal with D3h symmetry are given as ijk \(\equiv\) yyy = − yxx = − xxy = − xyx3,7 with x, y, z corresponding to the crystal coordinate system. The x and y axis refer to the zig–zag and arm-chair directions. The nonlinear wave propagation equation is solved using the wave optics module in COMSOL using the direct finite element method (FEM) solver in frequency domain29. The input fundamental excitation considered here is a focused Gaussian beam within the first solver. The spot radius and peak electric field are calculated and fed into the COMSOL model using the objective lens numerical aperture, incident average power and femtosecond laser specifications used in the experiments. The nonlinear polarization is defined only in the SnSe2 region as given by the equation above. This acts as the source for SHG emission for the second solver to solve for the second harmonic field. The propagating SHG field is collected at a monitor plane to calculate the overall SHG signal.

SHG polarization studies

The six-fold polarization dependent SHG plot obtained for crystals with D3h symmetry can be theoretically fitted with the SHG signal dependence with polarization angle given as: I||= I0 sin2(3θ + 3Φo) and I⊥ = I0 cos2(3θ + 3Φo) for parallel and perpendicular orientations respectively3. Here, θ refers to the rotation angle of the crystal axis with respect to the lab coordinates and Φo refers to the initial offset of the crystal axis with respect to the lab coordinates. For the nonlinear wave simulation, we simulated for I|| assuming θ = Φo = 0, considering the maximum SHG signal orientation along the arm-chair axis in order to explain the thickness dependence SHG and extract the nonlinear optical susceptibility. Thus, \({\chi }^{\left(2\right)}\) specified without subscripts refers to the \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}\) component.

Extracting the second order nonlinear optical susceptibility

To extract the second order nonlinear susceptibility of SnSe2, we first calculate the backward SHG emission from a Z-cut quartz sample with input gaussian beam focused within the thick quartz sample. Here, the non-resonant nonlinear susceptibility of quartz is taken as: \({\chi }_{quartz}^{\left(2\right)}\) = 0.6 pm/V and is considered approximately constant across the different excitation wavelengths considered8. The backward SHG emission from the SnSe2 layer is simulated using the alternating layer model as described in the “Results and Discussion” section for a range of values of nonlinear susceptibility (1–100 pm/V in a steps of 2 pm/V) for the same set of input source parameters as used for quartz SHG simulation. The backward simulated SHG ratio is obtained by taking a ratio of SHG emission from SnSe2 to quartz. The effective nonlinear susceptibility of SnSe2 is then extracted by comparing the simulated SHG ratio with the experimental SHG ratio. For all the simulation, the complex refractive index spectrum for SnSe2 is obtained from ref.30.

References

Autere, A. et al. Nonlinear optics with 2D layered materials. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705963. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201705963 (2018).

You, J. W., Bongu, S. R., Bao, Q. & Panoiu, N. C. Nonlinear optical properties and applications of 2D materials: Theoretical and experimental aspects. Nanophotonics 8, 63–97. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2018-0106 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Probing symmetry properties of few-layer MoS2 and h-BN by optical second-harmonic generation. Nano Lett. 13, 3329–3333. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl401561r (2013).

Seyler, K. L. et al. Electrical control of second-harmonic generation in a WSe2 monolayer transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 407–411. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.73 (2015).

Klein, J. et al. Electric-field switchable second-harmonic generation in bilayer MoS2 by inversion symmetry breaking. Nano Lett. 17, 392–398 (2017).

Malard, L. M., Alencar, T. V., Barboza, A. P. M., Mak, K. F. & De Paula, A. M. Observation of intense second harmonic generation from MoS2 atomic crystals. Phys. Rev. B 87, 201401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.161403 (2013).

Kumar, N. et al. Second harmonic microscopy of monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 161403. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.161403 (2013).

Boyd, R.W. Nonlinear Optics. Academic Press. ISBN: 9780123694706 (2020).

Gonzalez, J. M. & Oleynik, I. I. Layer-dependent properties of SnS2 and SnSe2 two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. B 94, 125443. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.94.125443 (2015).

Luppi, E., Hübener, H. & Véniard, V. Ab initio second-order nonlinear optics in solids: Second-harmonic generation spectroscopy from time-dependent density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 82, 235201. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.82.235201 (2010).

Shoji, I., Kondo, T., Kitamoto, A., Shirane, M. & Ito, R. Absolute scale of second-order nonlinear-optical coefficients. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 14, 2268–2294. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.14.002268 (1997).

Evans, B. L. & Hazelwood, R. A. Optical and electrical properties of SnSe2. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2, 1507. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/2/11/304 (1969).

Saito, R., Tatsumi, Y., Huang, S., Ling, X. & Dresselhaus, M. S. Raman spectroscopy of transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 353002. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/28/35/353002 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Synthesis and surface-enhanced Raman scattering of ultrathin SnSe2 nanoflakes by chemical vapor deposition. Nanomaterials 8, 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8070515 (2018).

Yu, P. et al. Fast photoresponse from 1T tin diselenide atomic layers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201503789 (2016).

Liu, J. S. et al. SnSe2 nanosheets for sub-picosecond harmonic mode-locked pulse generation. Small 15(38), 1902811. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201902811 (2019).

Cheng, C., Li, Z., Dong, N., Wang, J. & Chen, F. Tin diselenide as a new saturable absorber for generation of laser pulses at 1μm. Opt. Express 25, 6132–6140. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.25.006132 (2017).

Dandu, M. et al. Strong single-and two-photon luminescence enhancement by nonradiative energy transfer across layered heterostructure. ACS Nano 13, 4795–4803. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b01553 (2019).

Biswas, R. et al. Third-harmonic generation in multilayer Tin diselenide under the influence of Fabry–Perot interference effects. Opt. Express 27, 28855–28865. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.27.028855 (2019).

Rosa, H. G. et al. Characterization of the second-and third-harmonic optical susceptibilities of atomically thin tungsten diselenide. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28374-1 (2018).

Fan, X., Siris, R., Hartwig, O., Duesberg, G. S. & Niklaus, F. Rapid and large-area visualization of grain boundaries in MoS2 on SiO2 using vapor hydrofluoric acid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 34049–34057. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c06910 (2020).

Psilodimitrakopoulos, S. et al. Ultrahigh-resolution nonlinear optical imaging of the armchair orientation in 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Light Sci. Appl. 7, 18005–18005. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2018.5 (2018).

Psilodimitrakopoulos, S. et al. Twist angle mapping in layered WS2 by polarization-resolved second harmonic generation. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50534-0 (2019).

Attanayake, N. H. et al. Effect of intercalated metals on the electrocatalytic activity of 1T-MoS2 for the hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00865 (2017).

Wang, M. et al. Nonlinear optical imaging, precise layer thinning, and phase engineering in MoTe2 with femtosecond laser. ACS Nano 14, 11169–11177. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c02649 (2020).

Smith, A. J., Meek, P. E. & Liang, W. Y. Raman scattering studies of SnS2 and SnSe2. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 10, 1321. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3719/10/8/035 (1977).

Tian, Z. et al. Lateral heterostructures formed by thermally converting n-type SnSe2 to p-type SnSe. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 12831–12838. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b01235 (2018).

Panday, S. R. & Fregoso, B. M. Strong second harmonic generation in two-dimensional ferroelectric IV-monochalcogenides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 43LT01. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/aa8bfc (2017).

COMSOL Multiphysics® v. 5.6. COMSOL AB, Stockholm, Sweden. https://www.comsol.co.in/.

El-Nahass, M. M. Optical properties of tin diselenide films. J. Mater. Sci. 27, 6597–6604. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01165942 (1992).

Kudryavtsev, A. V., Lavrov, S. D., Shestakova, A. P., Kulyuk, L. L. & Mishina, E. D. Second harmonic generation in nanoscale films of transition metal dichalcogenide: Accounting for multipath interference. AIP Adv. 6, 095306. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4962764 (2016).

Youngblood, N., Peng, R., Nemilentsau, A., Low, T. & Li, M. Layer-tunable third-harmonic generation in multilayer black phosphorus. ACS Photonics 4, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00639 (2017).

Zhao, M. et al. Atomically phase-matched second-harmonic generation in a 2D crystal. Light Sci. Appl. 5, e16131–e16131. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2016.131 (2016).

Murzina, T. V., Maydykovskiy, A. I., Gavrilenko, A. V. & Gavrilenko, V. I. Optical second harmonic generation in semiconductor nanostructures. Phys. Res. Int. 2012, 836430. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/836430 (2012).

Daum, W. Optical studies of Si/SiO2 interfaces by second-harmonic generation spectroscopy of silicon interband transitions. Appl. Phys. A 87, 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-007-3913-0 (2007).

Higashitarumizu, N. et al. Purely in-plane ferroelectricity in monolayer SnS at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16291-9 (2020).

Song, Y. et al. Extraordinary second harmonic generation in ReS2 atomic crystals. ACS Photonics 5, 3485–3491. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00685 (2018).

Hsu, W. T. et al. Second harmonic generation from artificially stacked transition metal dichalcogenide twisted bilayers. ACS Nano 8, 2951–2958. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn500228r (2014).

Dandu, M., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T., Sood, A. K. & Majumdar, K. Spectrally tunable, large Raman enhancement from nonradiative energy transfer in the van der Waals heterostructure. ACS Photonics 7, 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.9b01648 (2020).

Datta, I. et al. Low-loss composite photonic platform based on 2D semiconductor monolayers. Nat. Photonics 14, 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-020-0590-4 (2020).

Singh, A. et al. Refractive uses of layered and two-dimensional materials for integrated photonics. ACS Photonics 7, 3270–3285. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.0c00915 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from DST Quantum Technologies program (QUST) and MeitY funding for the Center for Excellence in Quantum Technologies at IISc. AFM imaging was carried out at Micro and Nano Characterization Facility (MNCF), IISc Bengaluru.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B. and V.R. proposed the experiments to be performed. R.B. and A.P. performed the nonlinear optical microscopy experiments. M.D. and S.D. prepared the samples used in this study and performed Raman spectroscopy measurements. S.M. and J.D. performed the A.F.M. imaging. R.B. wrote the initial draft. All the authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biswas, R., Dandu, M., Prosad, A. et al. Strong near band-edge excited second-harmonic generation from multilayer 2H Tin diselenide. Sci Rep 11, 15017 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94612-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94612-8

This article is cited by

-

Thickness-Dependent Electrical and Optoelectrical Properties of SnSe2 Field-Effect Transistors

Electronic Materials Letters (2025)