Abstract

This study is devoted to the numerical assessment of the influence of helical baffle on the hydrothermal aspects and irreversibility behavior of the turbulent forced convection flow of water-CuO nanofluid (NF) inside a hairpin heat exchanger with 100 mm length, 10 mm inner tube internal diameter, and 15 mm outer diameter internal diameter. The variations of the first-law and second-law performance metrics are investigated in terms of Reynolds number (Re = 5000–10,000), volume concentration of NF (\(\varphi =0-4\mathrm{\%}\)) and baffle pitch (B = 25–100 mm). The results show that the NF Nusselt number grows with the rise of both the Re and \(\varphi\) whereas it declines with the rise of B. In addition, the outcomes depicted that the rise of both Re and \(\varphi\) results in the rise of pressure drop, while it declines with the increase of B. Moreover, it was found that the best thermal performance of NF is equal to 1.067, which belongs to the case B = 33.3 mm, \(\varphi\)=2%, and Re = 10,000. Furthermore, it was shown that irreversibilities due to fluid friction and heat transfer augment with the rise of Re while the rise of B results in the decrease of frictional irreversibilities. Finally, the outcomes revealed that with the rise of B, the heat transfer irreversibilities first intensify and then diminish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well known that the turbulent flow has a higher heat exchange rate and pumping power than the laminar flow, the former being desirable and the latter undesirable1,2,3. So, this idea came into the researchers' minds to put equipment in the path of laminar flow and create local turbulence4,5,6,7,8,9. The idea was very successful and was widely used in the industry today10,11,12. This equipment is called turbulator, and so far, various types of turbulators were introduced and their performance was studied experimentally and numerically. Also, the use of nanostructures was developed to increase the efficiency of engineering systems13,14,15,16.

Although the use of turbulators has led to an improvement in the performance of heat transfer systems, this has not prevented researchers from looking for ways to further improve the performance of these systems. One of these amazing techniques, which are originated from the low thermal conductivity of heat transfer fluids, is the use of nanofluids (NFs) instead of common heat transfer fluids17,18,19. Choi20 first made these modern fluids and called them NFs. After the introduction of NFs and their amazing thermal properties, much research was done on their performance in diverse applications such as thermal management of electronic components21,22 and photovoltaic panels23,24, nuclear applications25,26, and performance improvement of solar thermal collectors27,28,29, heat exchangers30,31,32 and car radiators33,34,35. The literature inspection shows that the performance of thermal systems with NF coolants equipped with turbulators was investigated by various researchers. Bellos et al.36 analyzed the efficacy of oil-CuO NF in a parabolic trough collector equipped with turbulators. They found that using the combination of NF and turbulator causes a 1.54% thermal efficiency improvement. Nakhchi and Esfahani37 inspected the efficacy of aqueous Cu NF inside a heated tube equipped with the perforated conical rings in a turbulent regime. It was reported that using compound NF and turbulator results in considerable heat transfer intensification. Akyurek et al.38 experimentally evaluated the forced convection flow of water-Al2O3 NF inside a horizontal tube equipped with a wire coil turbulator. They utilized two turbulators with different pitches and found that the performance metrics of a tube filled with NF without any turbulator are superior to that of the cases with turbulator. Xiong et al.39 simulated the efficacy of aqueous CuO NF flowing inside a tube having a compound turbulator. The outcomes portrayed that using turbulator elevates the rate of heat exchange between tube wall and NF. Xiong et al.40 numerically investigated the forced convection of NF through a pipe equipped with a complex-shaped turbulator. They inspected the consequence of elevating width ratio, flow rate, and pitch ratio on the performance features. It was found that the Nusselt number intensifies with boosting pitch ratio of turbulator. In a numerical investigation, Ahmed et al.41 explored the forced convection of water-Al2O3 and water-CuO NFs inside a triangular duct with a delta-winglet pair of turbulator under a turbulent flow regime. They reported the significant effect of using both NF and turbulator on the performance aspects. The design of a heat transfer system can be done both according to the first law and the second law of thermodynamics. If the first law applies, the system must have the highest overall hydrothermal performance, and if the second law applies, the system performance must have the least irreversibility. The efficacy of NF flow in turbulator-equipped thermal units has rarely been investigated from a second-law perspective42,43,44,45. Sheikholeslami et al.42 inspected the irreversibility features of turbulent flow of aqueous CuO NF inside a pipe equipped with complex turbulators. Li et al.43 simulated the NF irreversibility in a tube with helically twisted tapes. The thermal irreversibility was found to be declined with elevating the height ratio of turbulator, while the opposite was true for the frictional irreversibility. Farshad and Sheikholeslami44 analyzed the irreversibility aspects for aqueous Al2O3 NF flow in a solar collector having a twisted tape. The outcomes revealed that the irreversibility diminishes with the increase of diameter ratio. Al-Rashed et al.45 examined the influence of nanomaterial type on the irreversibility production of an NF in a heat exchanger. It was reported that the maximum irreversibility belongs to the platelet shape nanomaterials.

This numerical work aims to evaluate the features of turbulent flow of water-CuO NF through a hairpin heat exchanger equipped with helical baffles in the annulus side from both the first and second-law perspectives. The impacts of \(B\), \(Re\), and \(\varphi\) on the NF efficacy are assessed. This investigation is the first work on the consequences of using a helical baffle on the irreversibility production inside the annulus of a hairpin heat exchanger filled with NF.

Problem statement

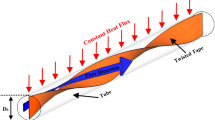

Figure 1 gives a demonstrative sketch of the geometry under investigation. It is a hairpin heat exchanger with 100 mm length, 10 mm inner tube internal diameter, and 15 mm outer diameter internal diameter. Additionally, the wall thickness for both the inner and outer tubes is 1 mm. Moreover, the considered \(B\) values are 25 mm, 33 mm, 50 mm, and 100 mm. The purpose of using this device is to cool the water-CuO NF passing through the annulus with the help of water passing through the inner tube. In both water and NF streams, time is of the essence and both streams are in a turbulent regime. Both streams enter the device at a uniform velocity and temperature and are discharged into the atmosphere and as a result, the relative pressure at the outlets is zero. Also, the exterior wall of the heat exchanger is considered insulated and the no-slip condition is utilized on the walls.

Governing equations and problem parameters

To simulate the steady, incompressible, and turbulent flow of nanofluid and water in the annulus and inner tube of the hairpin heat exchanger studied in the present study, the conservation equations of mass, momentum, and energy must be solved. These equations are as follows46,47,48:

-

Continuity equation

$$\frac{\partial \left({u}_{i}\right)}{\partial {x}_{i}}=0$$(1) -

Momentum equation

$$\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{j}}\left({u}_{j}{\rho }_{nf}{u}_{i}\right)=-\frac{\partial p}{\partial {x}_{i}}+\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{j}}\left[{\mu }_{nf}\left(\frac{\partial {u}_{i}}{\partial {x}_{j}}+\frac{\partial {u}_{j}}{\partial {x}_{i}}\right)\right]+\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{j}}\left(-{\rho }_{nf}\overline{{u }_{j}^{^{\prime}}{u}_{i}^{^{\prime}}}\right)$$(2) -

Energy equation

$$\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{i}}\left({\rho }_{nf}{Tu}_{i}\right)=\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{i}}\left[\left({\mu }_{t}/{Pr}_{t}+{\mu }_{nf}/{Pr}_{nf}\right)\frac{\partial T}{\partial {x}_{i}}\right]$$(3)where \({\mu }_{t}\) and \({\rho }_{nf}\overline{{u }_{j}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}{u}_{i}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}}\) are defined as follows;

$${\mu }_{t}={\rho }_{nf}{C}_{\mu }{k}^{2}/\varepsilon$$(4)$${\mu }_{t}\left(\frac{\partial {u}_{i}}{\partial {x}_{j}}+\frac{\partial {u}_{j}}{\partial {x}_{i}}\right)-\frac{2}{3}{\delta }_{ij}\left({\rho }_{nf}k+{\mu }_{t}\frac{\partial {u}_{k}}{\partial {x}_{k}}\right)=-{\rho }_{nf}\overline{{u }_{j}^{^{\prime}}{u}_{i}^{^{\prime}}}$$(5)The \(k\)-\(\varepsilon\) turbulence scheme is employed to establish the turbulence. To this end, two additional equations for turbulent kinetic energy (\(k\)) and the turbulent dissipation rate (\(\varepsilon\)) are added which are as follows42:

$$\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{j}}\left[\frac{\partial k}{\partial {x}_{j}}\left({\mu }_{nf}+\frac{{\mu }_{t}}{{\sigma }_{k}}\right)\right]-{\rho }_{nf}\varepsilon +{G}_{k}=\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{i}}\left({u}_{i}{\rho }_{nf}k\right)$$(6)$$\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{i}}\left({\rho }_{nf}{u}_{i}\varepsilon \right)=\frac{\partial }{\partial {x}_{j}}\left[\frac{\partial \varepsilon }{\partial {x}_{j}}\left({\mu }_{nf}+\frac{{\mu }_{t}}{{\sigma }_{\varepsilon }}\right)\right]+\frac{\varepsilon }{k}{G}_{k}{C}_{1\varepsilon }-{\rho }_{nf}\frac{{\varepsilon }^{2}}{k}{C}_{2\varepsilon }$$(7)where \({G}_{k}=-\frac{\partial {u}_{j}}{\partial {x}_{i}}{\rho }_{nf}\overline{{u }_{j}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}{u}_{i}^{\mathrm{^{\prime}}}}\), \({Pr}_{t}=0.85\); \({C}_{\mu }=0.0845\); \({\sigma }_{k}=1\); \({\sigma }_{\varepsilon }=1.3\); \({C}_{1\varepsilon }=1.42\); \({C}_{2\varepsilon }=1.68\).

The irreversible generation in forced convection flow of NF flow is due to two sources, namely fluid friction and heat exchange. Therefore, the total irreversibility is computed as47:

$$\begin{gathered} {S_{{gen}} = \underbrace {{\frac{{\mu _{{nf}} }}{{T_{0} }}\left\{ {2\left[ {\left( {\frac{{\partial u}}{{\partial x}}} \right)^{2} + \left( {\frac{{\partial v}}{{\partial y}}} \right)^{2} + \left( {\frac{{\partial w}}{{\partial z}}} \right)^{2} } \right] + \left( {\frac{{\partial u}}{{\partial y}} + \frac{{\partial v}}{{\partial x}}} \right)^{2} + \left( {\frac{{\partial u}}{{\partial z}} + \frac{{\partial w}}{{\partial x}}} \right)^{2} + \left( {\frac{{\partial w}}{{\partial y}} + \frac{{\partial v}}{{\partial z}}} \right)^{2} } \right\}}}_{{S_{{gen,f}} }}} \hfill \\ + \underbrace {{\frac{{k_{{nf}} }}{{T_{0}^{2} }} + \left[ {\left( {\frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial x}}} \right)^{2} + \left( {\frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial y}}} \right)^{2} + \left( {\frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial z}}} \right)^{2} } \right]}}_{{S_{{gen,t}} }} \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$(8)By integrating the whole computational domain, the total irreversibility can be obtained as 47:

$${S}_{tot}=\int {S}_{gen}\,dv$$(9) -

Bejan number49:

$$Be=\frac{{S}_{gen,t}}{{S}_{tot}}$$(10)The characteristic of an NF includes its thermophysical properties that establish the relationship between the base fluid and the nanoparticles. These basic relationships for the water-CuO NF are defined as follows50,51,52,53:

$${\rho }_{nf}={\rho }_{f}\left(1-\varphi \right)+{\rho }_{p}\varphi$$(11)$${\left(\rho {C}_{p}\right)}_{nf}={\left(\rho {C}_{p}\right)}_{f}\left(1-\varphi \right)+{\left(\rho {C}_{p}\right)}_{p}\varphi$$(12)$${k}_{nf}={k}_{f}\frac{{k}_{p}+2{k}_{f}+2\varphi \left({k}_{p}-{k}_{f}\right)}{{k}_{p}+2{k}_{f}-\varphi \left({k}_{p}-{k}_{f}\right)}$$(13)$${\mu }_{nf}=\left(123{\varphi }^{2}+7.3\varphi +1\right){\mu }_{f}$$(14)The heat transfer rates for hot and cold fluids are calculated as follows:

$${q}_{h}={\dot{m}}_{h}{C}_{p,h}\left({T}_{h,i}-{T}_{h,o}\right)$$(15)$${q}_{c}={\dot{m}}_{c}{C}_{p,c}\left({T}_{c,i}-{T}_{c,o}\right)$$(16) -

Average Nusselt number10:

$$Nu=\frac{h{D}_{h}}{{k}_{f}}$$(17) -

The heat transfer coefficient54,55,56:

$$h=\frac{{q}^{{{\prime\prime}}}}{{\Delta T}_{LMTD}}$$(18)

where

where

\({q}^{\prime\prime}\) is the total heat flux that the fluid receives over the entire computational domain and is calculated as follows:

The pressure drop \(\left(\Delta P\right)\) is defined as follows:

Thermal performance can be computed as:

Numerical scheme, validation, and grid independency

In the current numerical investigation, the simulations were conducted using the ANSYS Fluent 18.1 software. The governing equations were discretized using the second-order upwind technique. Besides, the SIMPLE scheme was utilized to perform the pressure–velocity coupling. The convergence metric was set to 10–657,58,59,60,61,62,63. Four different types of grids were used to make the outputs of the problem independent of the mesh. The tetrahedral mesh was used. The walls had a boundary layer mesh with a factor of 5%. The Nusselt number was used to perform the mesh study. Finally, it was found that the most appropriate mesh is the one with a 650,538 element number. To ensure the accuracy and validity of the results of the present work, the experimental findings of Wen and Ding64 and the numerical outcomes of Goktepe et al.65 for the local convection coefficient of NF flowing through a uniformly heated tube were employed. The outcomes are reported in Fig. 2. As can be observed, there is a good consistency between the outcomes, and the largest discrepancy between our results and the data from the other works (i.e. Refs.64,65) is 10%. To further validate the simulations, the average Nusselt number of NF flow inside a channel with rectangular rib (in-line) reported by Vanaki and Mohammed66 was compared with our results. As can be seen in Fig. 3, at low velocities, a good consistency is observed, and as the flow velocity elevates, the discrepancy of the results is elevated and reaches 7%.

Validation with numerical work66.

Results and discussion

The main focus of this numerical investigation is to analyze the turbulent flow of water-CuO NF inside a hairpin heat exchanger with the helical baffle on the annulus side. The effects of \(\varphi\) (0–4%), \(Re\) (5000–10,000), and \(B\) (25–100 mm) on the performance metrics are investigated. Figure 4 depicts the contour plots of NF velocity and temperature for different values of \(B\) at \(Re=5000\) and \(\varphi =4\%\). It is seen that as \(B\) augments, the NF velocity diminishes.

Figure 5 gives the consequences of elevating \(Re\) on the velocity and temperature contours of NF for \(B\)=25 mm. As is seen, intensifying the \(Re\) entails an elevation in the NF velocity and a decrement in the NF temperature.

Figure 6 gives the Nusselt number in terms of \(B\) for various \(\varphi\). The Nusselt number improves by elevating both the \(Re\) and \(\varphi\), while it declines by augmenting the \(B\). For instance, at \(Re=5000\) and \(\varphi =0\%\), elevating the \(B\) from 25 to 100 mm results in a 19.05% decrease in the Nusselt number of NF, while this amount for \(\varphi =\) 4% is 15.62%. In addition, at \(B\)=25 mm and \(\varphi =4\%\), intensification of \(Re\) from 5000 to 10,000 causes a 61.83% decline in the Nusselt number of NF. Elevating the \(Re\) entails a rise in the thickness of the velocity and thermal boundary layer, which elevates the temperature gradient and, consequently, elevates the convective heat transfer coefficient and Nusselt number. Moreover, intensification of \(\varphi\) causes augmentation in the \({k}_{nf}\) and, thereby, an augmentation in the convective heat transfer and Nusselt number. Furthermore, intensifying the baffle pitch entails a decrease in the NF velocity and, therefore, a decrease in the convective heat transfer coefficient and Nusselt number.

One of the important issues when choosing a working fluid is that the fluid performance should be examined from both the heat transfer and pressure drop (pumping power) aspects. Figure 7 gives the variations of the pressure drop of NF versus \(\varphi\) and \(B\) for different \(Re\). It is observed that the pressure drop intensifies by boosting both the \(\varphi\) and \(Re\), while it reduces by boosting the \(B\). For example, at \(Re=5000\) and \(\varphi =0\%\), boosting the \(B\) from 25 to 100 mm results in a 73.59% reduction in the pressure drop of NF, while this amount for \(\varphi =\) 4% is 73.55%. Additionally, at \(B\)=25 mm and \(\varphi =4\%\), augmentation of \(Re\) from 5000 to 10,000 results in a 232.82% decrease in the pressure drop of NF. Boosting both the \(Re\) and \(\varphi\) causes an elevation in the NF velocity and, therefore, according to Eq. (24), the pressure drop of NF elevates. On the other hand, elevating the \(B\) causes an increment in the annulus fluid path and, as a result, an elevation in the pressure drop, while the NF velocity declines by boosting the \(B\) which results in a decrease in the pressure drop of NF. According to the obtained results, it can be concluded the effect of elevated annulus flow path on the pressure drop outweighs the effect of decreased NF velocity and, therefore, the NF pressure drop reduces with an elevation in the \(B\).

The results presented so far have shown that intensifying the \(\varphi\) entails an elevated Nusselt number and pressure drop, which the first is a favorable effect and the latter is undesirable. For the final decision on the usefulness of using NF in the heat exchanger under investigation, the performance index should be examined. Figure 8 demonstrates the variations of the performance index versus \(\varphi\) and \(B\) for different \(Re\) values. The outcomes reveal that the hydrodynamic performance of the water-CuO NF in the considered heat exchanger is superior to that of the pure water in just the following four cases:

-

\(B=100\) mm, \(\varphi =4\%\) and \(Re=5000\) where \(\eta =1.029\).

-

\(B=33.3\) mm, \(\varphi =2\%\) and \(Re=10000\) where \(\eta =1.067\).

-

\(B=33.3\) mm, \(\varphi =4\%\) and \(Re=10000\) where \(\eta =1.054\).

-

\(B=100\) mm, \(\varphi =2\%\) and \(Re=10000\) where \(\eta =1.000\).

In the remainder of this section, the flow of water-CuO NF with \(\varphi =2\%\) in the considered heat exchanger is examined from the perspective of irreversibility production. Figure 9 displays the influences of \(Re\) and \(B\) on the frictional irreversibility of NF. As can be seen, the frictional irreversibility declines and rises with increasing \(B\) and \(Re\), respectively, and the \(Re\) effect on the frictional irreversibility at lower \(B\) is greater. For example, at \(Re=5000\), increasing the \(B\) from 25 to 100 mm results in a 67.84% decrease in frictional irreversibility. In addition, at \(B=100\) mm, the augmentation of \(Re\) from 5000 to 10,000 causes a 209.45% increment in the frictional irreversibility. By boosting the \(Re\) at a constant \(\varphi\) (i.e. constant Prandtl number) and \(B\), the thickness of the velocity boundary layer decreases, which results in an elevated velocity gradient and thus elevated frictional irreversibility. On the other hand, increasing the \(Re\) at a constant \(\varphi\) and \(B\), results in an elevated NF velocity and hence a decrease in the average NF temperature which results in elevated frictional irreversibility. Elevating the \(B\) results in a decrease in the flow mixing, which results in a decrease in the velocity gradient and a decrease in the NF temperature, which in turn decreases and elevates the frictional irreversibility. It can be concluded that the decreasing effect of velocity gradient on the frictional irreversibility is overcome by the increasing effect of NF temperature and, therefore, the frictional irreversibility decreases with increasing \(B\).

Figure 10 gives the changes of thermal irreversibility of NF with \(\varphi =2\%\) versus \(B\) in terms of \(Re\). It is seen that the thermal irreversibility declines with the elevation of \(Re\). For example, at \(B=100\) mm, the intensification of \(Re\) from 5000 to 10,000 causes a 52.57% decrease in thermal irreversibility. As mentioned before, the NF temperature decreases with increasing \(Re\) at a constant \(\varphi\) and \(B\), which results in elevated thermal irreversibility. Also, the augmentation of \(Re\) results in improved mixing of the flow and consequently, a decrease in the temperature gradient which ultimately results in a decrease in the thermal irreversibility. It can be said that the impact of temperature gradient on the thermal irreversibility outweighs the impact of NF temperature and therefore, the thermal irreversibility declines with the rise of \(Re\). Moreover, Fig. 10 shows that with the rise of \(B\) at a constant \(Re\) and \(\varphi\), the thermal irreversibility first elevates and then reduces. The highest thermal irreversibility occurs at \(B\)=50 mm. Boosting of \(B\) at a constant \(\varphi\) and \(Re\) reduces the flow mixing which results in the decrease of both the NF temperature and temperature gradient which respectively elevates and diminishes the rate of thermal irreversibility. Figure 10 reveals that for the \(B\) lower than 50 mm, the increasing impact of temperature outweighs the decreasing of the temperature gradient, and ultimately, the thermal irreversibility declines while the opposite is true for the \(B\) higher than 50 mm.

The results presented in Figs. 9 and 10 show that increasing the baffle pitch results in a decrease in both the thermal and frictional irreversibilities, and therefore, it can be easily deduced that increasing the \(B\) entails a declined total irreversibility. However, the influence of \(Re\) on the total irreversibility cannot be predicted because the thermal irreversibility elevates with decreasing \(Re\) and then decreases.

Conclusion

In this study, the first law and the second law of thermodynamics are employed to investigate the turbulent flow of aqueous CuO NF through a hairpin heat exchanger equipped with the helical baffle on the annulus side. The influence of \(Re\) (5000–10,000), \(\varphi\) (0–4%), and \(B\) (25–100 mm) on the performance metrics are assessed. The following results can be deduced from this simulation:

-

With the rise of \(B\) at a constant \(Re\) and \(\varphi\), the thermal irreversibility first elevates and then reduces.

-

Intensifying the \(Re\) entails an elevated NF velocity and a declined NF temperature.

-

Pressure drop intensifies by boosting both the \(\varphi\) and \(Re\), while it reduces by boosting the \(B\).

-

Frictional irreversibility declines and rises with increasing \(B\) and \(Re\), respectively.

-

\(Re\) effect on the frictional irreversibility at lower \(B\) is greater.

In future studies, the effect of using perforated and porous turbulators on the results presented in the present study will be investigated.

Change history

18 January 2023

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28023-2

Abbreviations

- \(B\) :

-

Baffle pitch (mm)

- \(Be\) :

-

Bejan number

- \({C}_{p}\) :

-

Specific heat capacity (J/kg.K)

- \({D}_{h}\) :

-

Hydraulic diameter (m)

- \(f\) :

-

Friction factor

- \(h\) :

-

Convection coefficient (W/m2.K)

- \(k\) :

-

Turbulent kinetic energy (m2/s2)

- \({k}_{f}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity of base fluid (W/m.K)

- \({k}_{nf}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity of nanofluid (W/m.K)

- \({k}_{p}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity of nanoparticles (W/m.K)

- \(L\) :

-

Length (m)

- \({\dot{m}}_{c}\) :

-

Mass flow rate of cold fluid (kg/s)

- \({\dot{m}}_{h}\) :

-

Mass flow rate of hot fluid (kg/s)

- \(Nu\) :

-

Nusselt number

- \(p\) :

-

Pressure (Pa)

- \(Pr\) :

-

Prandtl number

- \({Pr}_{t}\) :

-

Turbulent Prandtl number

- \({q}_{c}\) :

-

Heat transfer rate for cold fluid (W)

- \({q}_{h}\) :

-

Heat transfer rate for hot fluid (W)

- \({q}^{\prime\prime}\) :

-

Heat flux (W/m2)

- \({S}_{gen}\) :

-

Local entropy generation rate (W/m3.K)

- \({S}_{tot}\) :

-

Global entropy generation rate (W/K)

- \(T\) :

-

Temperature (K)

- \({u}_{i}\) :

-

Velocity (m/s)

- \({u}_{i}^{^{\prime}}\) :

-

Turbulent velocity fluctuation (m/s

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Turbulent dissipation rate (m2/s3)

- \({\rho }_{f}\) :

-

Density of base fluid (kg/m3)

- \({\rho }_{nf}\) :

-

Density of nanofluid (kg/m3)

- \({\rho }_{p}\) :

-

Density of nanoparticles (kg/m3)

- \({\mu }_{nf}\) :

-

Viscosity of nanofluid (kg/m.s)

- \({\mu }_{t}\) :

-

Turbulent viscosity (kg/m.s)

- \(\varphi\) :

-

Volume concentration of nanofluid (%)

- \(\eta\) :

-

Thermal performance indicator

References

Samadifar, M. & Toghraie, D. Numerical simulation of heat transfer enhancement in a plate-fin heat exchanger using a new type of vortex generators. Appl. Therm. Eng. 133, 671–681 (2018).

Toghraie, D. Numerical thermal analysis of water's boiling heat transfer based on a turbulent jet impingement on heated surface. Physica E 84, 454–465 (2016).

He, W. et al. Effect of twisted-tape inserts and nanofluid on flow field and heat transfer characteristics in a tube. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 110, 104440 (2020).

Moraveji, A. & Toghraie, D. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of heat transfer and fluid flow characteristics in a vortex tube by considering the various parameters. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 113, 432–443 (2017).

Bouhacina, B., Saim, R., Benzenine, H. & Oztop, H. F. Analysis of thermal and dynamic comportment of a geothermal vertical U-tube heat exchanger. Energy Build. 58, 37–43 (2013).

Bouhacina, B., Saim, R. & Oztop, H. F. Numerical investigation of a novel tube design for the geothermal borehole heat exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 79, 153–162 (2015).

Chupradit, S. et al. Use of Organic and Copper-Based Nanoparticles on the Turbulator Installment in a Shell Tube Heat Exchanger: A CFD-Based Simulation Approach by Using Nanofluids. J. Nanomater. 3250058 (2021).

Mousavi Ajarostaghi, Seyed Soheil et al., Numerical evaluation of the heat transfer enhancement in a tube with a curved conical turbulator insert, I nternational Journal of Ambient Energy, 2021.

Farhad AFSHARPANAH, NUMERICAL INVESTIGATION OF NON-UNIFORM HEAT TRANSFER ENHANCEMENT IN PARABOLIC TROUGH SOLAR COLLECTORS USING DUAL MODIFIED TWISTED-TAPE INSERTS, Year 2021, Volume 7, Issue 1, 133 - 147, 01.01.2021.

Zaboli, M., Nourbakhsh, M. & Ajarostaghi, S. S. M. Numerical evaluation of the heat transfer and fluid flow in a corrugated coil tube with lobe-shaped cross-section and two types of spiral twisted tape as swirl generator. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 147, 999–1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-020-10219-7 (2022).

Nakhchi, M. E., Hatami, M. & Rahmati, M. Effects of CuO nano powder on performance improvement and entropy production of double-pipe heat exchanger with innovative perforated turbulators. Adv. Powder Technol. 32, 3063–3074 (2021).

Nakhchi, M. E. & Rahmati, M. T. Entropy generation of turbulent Cu–water nanofluid flows inside thermal systems equipped with transverse-cut twisted turbulators. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 143, 2475–2484 (2021).

Long, X. et al. Strain rate shift for constitutive behaviour of sintered silver nanoparticles under nanoindentation. Mechanics of materials. Mech. Mater. 158, 103881 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. A Novel Aluminum-Graphite Dual-Ion Battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 6(11), 1502588 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Operation optimization of electrical-heating integrated energy system based on concentrating solar power plant hybridized with combined heat and power plant. J. Clean. Prod. 289, 125712 (2021).

Zeng, K. et al. Molecular dynamic simulation and artificial intelligence of lead ions removal from aqueous solution using magnetic-ash-graphene oxide nanocomposite. J. Mol. Liq. 118290 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. Combustion process of nanofluids consisting of oxygen molecules and aluminum nanoparticles in a copper nanochannel using molecular dynamics simulation. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 28, 101628 (2021).

Fu, C. et al. Comprehensive investigations of mixed convection of Fe–ethylene-glycol nanofluid inside an enclosure with different obstacles using lattice Boltzmann method. Scientific Reports 11(1), 1–16 (2021).

Bokov, D. et al. Nanomaterial by Sol-Gel Method: Synthesis and Application. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng 5102014 (2021).

Choi, S. U. S. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. ASME FED 231, 99–105 (1995).

Shahsavar, A., Shahmohammadi, M. & Askari, E. B. CFD simulation of the impact of tip clearance on the hydrothermal performance and entropy generation of a water-cooled pin-fin heat sink. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 126, 105400 (2021).

El-Khouly, M. M., El Bouz, M. A. & Sultan, G. I. Experimental and computational study of using nanofluid for thermal management of electronic chips. J. Energy Storage 39, 102630 (2021).

Karaaslan, I. & Menlik, T. Numerical study of a photovoltaic thermal (PV/T) system using mono and hybrid nanofluid. Sol. Energy 224, 1260–1270 (2021).

Jidhesh, P., Arjunan, T. V. & Gunasekar, N. Thermal modeling and experimental validation of semitransparent photovoltaic- thermal hybrid collector using CuO nanofluid. J. Clean. Prod. 316, 128360 (2021).

Bhowmik, P. K., Shamim, J. A., Chen, X. & Suh, K. Y. Rod bundle thermal-hydraulics experiment with water and water-Al2O3 nanofluid for small modular reactor. Ann. Nucl. Energy 150, 107870 (2021).

P.K. Bhowmik, Nanofluid Operation and Valve Engineering of Super for Small Unit Passive Enclosed Reactor, Master's thesis, Department of Nuclear Engineering, Seoul National University, Seoul, South Korea, accessed Dec. 24, 2019, http://hdl.handle.net/10371/123511.

Rubbi, F. et al. State-of-the-art review on water-based nanofluids for low temperature solar thermal collector application. Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells 230, 111220 (2021).

Hosseini, S. M. S. & Dehaj, M. S. An experimental study on energetic performance evaluation of a parabolic trough solar collector operating with Al2O3/water and GO/water nanofluids. Energy 234, 121317 (2021).

Xiong, Q. et al. State-of-the-art review of nanofluids in solar collectors: A review based on the type of the dispersed nanoparticles. J. Clean. Prod, 310, 127528 (2021).

Jassim, E. I. & Ahmed, F. Assessment of nanofluid on the performance and energy-environment interaction of Plate-Type-Heat exchanger. Thermal Sci. Eng. Progr. 25, 100988 (2021).

Shahsavar, A., Rashidi, M., Yildiz, C. & Arici, M. Natural convection and entropy generation of Ag-water nanofluid in a finned horizontal annulus: A particular focus on the impact of fin numbers. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 125, 105349 (2021).

Shahsavar, A., Jamei, M. & Karbasi, M. Experimental evaluation and development of predictive models for rheological behavior of aqueous Fe3O4 ferrofluid in the presence of an external magnetic field by introducing a novel grid optimization based-Kernel ridge regression supported by sensitivity analysis. Powder Technol. 393, 1–11 (2021).

Arora, N. & Gupta, M. An updated review on application of nanofluids in flat tubes radiators for improving cooling performance. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 134, 110242 (2020).

Kaladgi, A. R. et al. Integrated Taguchi-GRA-RSM optimization and ANN modelling of thermal performance of zinc oxide nanofluids in an automobile radiator. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 26, 101068 (2021).

Abbas, F. et al. Towards convective heat transfer optimization in aluminum tube automotive radiators: Potential assessment of novel Fe2O3-TiO2/water hybrid nanofluid. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 124, 424–436 (2021).

Bellos, E., Tzivanidis, C. & Tsimpoukis, D. Enhancing the performance of parabolic trough collectors using nanofluids and turbulators. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 91, 358–375 (2018).

Nakhchi, M. E. & Esfahani, J. A. Numerical investigation of turbulent Cu-water nanofluid in heat exchanger tube equipped with perforated conical rings. Adv. Powder Technol. 30, 1338–1347 (2019).

Akyurek, E. F., Gelis, K., Sahin, B. & Manay, E. Experimental analysis for heat transfer of nanofluid with wire coil turbulators in a concentric tube heat exchanger. Results Phys. 9, 376–389 (2018).

Xiong, Q. et al. Macroscopic simulation of nanofluid turbulent flow due to compound turbulator in a pipe. Chem. Phys. 527, 110475 (2019).

Xiong, Q. et al. Modeling of heat transfer augmentation due to complex-shaped turbulator using nanofluid. Phys. A 540, 122465 (2020).

Ahmed, H. E. et al. Turbulent heat transfer and nanofluid flow in a triangular duct with vortex generators. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 105, 495–504 (2017).

Sheikholeslami, M. et al. Simulation of turbulent flow of nanofluid due to existence of new effective turbulator involving entropy generation. J. Mol. Liquids 291, 111283 (2019).

Li, Z., Sheikholeslami, M., Jafaryar, M., Shafee, A. & Chamkha, A. J. Investigation of nanofluid entropy generation in a heat exchanger with helical twisted tapes. J. Mol. Liq. 266, 797–805 (2018).

Farshad, S. A. & Sheikholeslami, M. Nanofluid flow inside a solar collector utilizing twisted tape considering exergy and entropy analysis. Renew. Energy 141, 246–258 (2019).

Al-Rashed, A. A. A. A. et al. Entropy generation of boehmite alumina nanofluid flow through a minichannel heat exchanger considering nanoparticle shape effect. Phys. A 521, 724–736 (2019).

Shahsavar, A., Noori, S., Toghraie, D. & Barnoon, P. Free convection of non-Newtonian nanofluid flow inside an eccentric annulus from the point of view of first-law and second-law of thermodynamics. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 101(5), e202000266 (2021).

El-Shorbagy, M. A. et al. Numerical investigation of mixed convection of nanofluid flow in a trapezoidal channel with different aspect ratios in the presence of porous medium. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 25, 100977 (2021).

Barnoon, P., Toghraie, D., Mehmandoust, B., Fazilati, M. A. & Eftekhari, S. A. Comprehensive study on hydrogen production via propane steam reforming inside a reactor. Energ. Rep. 7, 929–941 (2021).

Kanti, P. K., Sharma, K. V., Minea, A. A. & Kesti, V. Experimental and computational determination of heat transfer, entropy generation and pressure drop under turbulent flow in a tube with fly ash-Cu hybrid nanofluid. Int. J. Thermal Sci. 167, 107016 (2021).

Maxwell, J. C. Treatise on electricity and magnetism (Clarendon Press, 1873).

Brinkman, H. The viscosity of concentrated suspensions and solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 20, 571–577 (1952).

Pak, B. C. & Cho, Y. L. Hydrodynamic and heat transfer study of dispersed fluids with submicron metallic oxide particles. Exp. Heat Transfer Int. J. 11, 141–170 (1998).

Xuan, Y. & Roetzel, W. Conceptions for heat transfer correlation of nanofluids. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 43, 3701–3707 (2000).

Li, Z., Shahsavar, A., Niazi, K., Al-Rashed, A. A. A. A. & Rostami, S. Numerical assessment on the hydrothermal behavior and irreversibility of MgO-Ag/water hybrid nanofluid flow through a sinusoidal hairpin heat-exchanger. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 115, 104628 (2020).

Alsarraf, J., Moradikazerouni, A., Shahsavar, A., Afrand, M. & Tran, M. D. Hydrothermal analysis of turbulent boehmite alumina nanofluid flow with different nanoparticle shapes in a minichannel heat exchanger using two-phase mixture model. Phys. A 520, 275–288 (2019).

Shahsavar, A., Rahimi, Z. & Salehipour, H. Nanoparticle shape effects on thermal-hydraulic performance of boehmite alumina nanofluid in a horizontal double-pipe minichannel heat exchanger. Heat Mass Transf. 55, 1741–1751 (2019).

Yang, S. et al. Membrane distillation technology for molecular separation: a review on the fouling, wetting and transport phenomena. J. Mol. Liq. 118115 (2021).

Chupradit, S. et al. Pin angle thermal effects on friction stir welding of AA5058 aluminum alloy: CFD simulation and experimental validation. Materials 14(24), 7565 (2021).

Ren, J. & Khayatnezhad, M. Evaluating the stormwater management model to improve urban water allocation system in drought conditions. Water Supply 21(4), 1514–1524 (2021).

Zeraati, M., Alizadeh, V., Chupradit, S., Chauhan, N. P. S. & Sargazi, G. Green synthesis and mechanism analysis of a new metal-organic framework constructed from Al (III) and 3, 4-dihydroxycinnamic acid extracted from Satureja hortensis and its anticancerous activities. J. Mol. Struct. 1250, 131712 (2022).

Qaderi, J. A brief review on the reaction mechanisms of CO2 hydrogenation into methanol. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 3(2), 33–40 (2021).

Ruhani, B. et al, Numerical simulation of the effect of battery distance and inlet and outlet length on the cooling of cylindrical lithium-ion batteries and overall performance of thermal management system. J Energy Storage 45, 103714 (2022).

Ruhani B. et al, Comprehensive Techno-Economic Analysis of a Multi-Feedstock Biorefinery Plant in Oil-Rich Country: A Case Study of Iran. Sustainability 14(2), 1017 (2022)

Wen, D. & Ding, Y. Experimental investigation into convective heat transfer of nanofluids at the entrance region under laminar flow conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 47, 5181–5188 (2004).

Göktepe, S., Atalık, K. & Ertürk, H. Comparison of single and two-phase models for nanofluid convection at the entrance uniformly heated tube. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 80, 83–92 (2014).

Vanaki, S. M. & Mohammed, H. A. Numerical study of nanofluid forced convection flow in channels using different shaped transverse ribs. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 67, 176–188 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Program for Innovative Talents in Institutions of Higher Education of Liaoning Province (LR2019060).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript."

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28023-2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Baghaei, S., Suksatan, W. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Numerical assessment of the influence of helical baffle on the hydrothermal aspects of nanofluid turbulent forced convection inside a heat exchanger. Sci Rep 12, 2245 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06049-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06049-2