Abstract

Low planting density and irrational nitrogen (N) fertilization are two common practices in conventional cropping of smallholder maize production in Huanghuaihai region of China. A 2-year field experiment was carried out to study the effects of N application and planting density on maize phenology, dry matter accumulation, profit, yield, N uptake and efficiency indices. The experiments included three N application levels (120 kg ha−1, N1; 180 kg ha−1, N2; 240 kg ha−1, N3) and three planting densities (60,000 plants ha−1, D1; 75,000 plants ha−1, D2; 90,000 plants ha−1, D3). Increasing N input and planting density delayed the physiological maturity and enhanced dry matter accumulation. Comparing with the traditional N3 level, grain yield and profit were kept stable at N2 level and decreased at N1 level, partial factor productivity of applied N (PFPN) and nitrogen efficiency ratio (NER) were increased with the decreasing of N level. Comparing with the traditional D1 density, grain yield, profit and PFPN were increased at D2 density and then kept stable at D3 density, NER was kept stable at D2 density and then decreased at D3 density. Based on the predicted maximum profit, the optimal combinations of N application and planting density were 199 kg ha−1 and 81,081 plants ha−1 in 2017, and 205 kg ha−1 and 84,782 plants ha−1 in 2018. The two optimal combinations had an increase of 17.6% for grain yield, 39.8% for PEPN, 3.6% for NRE than the traditional N3D1 treatment. Therefore, an appropriate combination of increased planting density with reduced N application could enhance profit and nitrogen use of summer maize in Huanghuaihai region of China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 2020 World Population Data Sheet indicates that world population is expected to increase from 7.8 billion in 2020 to 9.9 billion by 2050. This is likely to drastically increase food demand over the coming decades. As a staple crop in the world, maize cultivation is essential for yield improvement to meet the increasing food demand.

An evaluation of long-term studies has shown that 40 to 60% of crop yield can be attributed to fertilizer inputs1,2. Nitrogen (N) fertilizer is one of the most vital inputs in maize production3. Increasing N application rate is an effective way of obtaining high yield4,5. However, excessive fertilization often leads to not only low N use efficiency but also serious threats to environment and human health3,6. Besides N fertilizer, increasing planting density is a way for increasing grain yield, as it improved the ability of the crop canopy to capture water, nutrients and light7,8. However, crowded maize plants under high planting density, will result in resource competition between plants and consequently lead to a yield reduction per plant9. Therefore, optimal N input and planting density are critical for maize production.

Optimal planting density for high yield should be associated with an appropriate N application10,11. In super high-yield maize experiments, an appropriate increase of planting density and a reasonable reduction of N application can not only achieve high maize yield but also raise the N utilization efficiency in Northwest China12. In China, Huanghuaihai region is one major maize planting area, with planting area and the production occupying 34.7% and 36.8% of the whole China13, respectively. In this region, some problems exist with the traditional management practices of smallholder farming, such as low planting density and irrational N fertilizer14,15. Therefore, agricultural strategy that aims to obtain high profit and resource efficiency by means of optimizing planting density and N application rate is on demand. In this study, we hypothesized that, in Huanghuaihai region of China, high yield, high N use efficiency, and high economic return could be obtained by increasing planting density and optimizing N application rate. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to (1) determine the impacts of N application rate and planting density on maize phenology, dry matter, yield, profit, and N use; and (2) to determine the combination of planting density and N application rate which maximize the profit and N use based on smallholder farming in Huanghuaihai region in China.

Results

Days to tasseling, silking and physiological maturity

As shown in Table 1, planting density had significant effects on days to tasselling and silking in 2017, and both N rate and planting density had significant effects on days to tasselling, silking and physiological maturity in 2018 (Table 1). The decreasing N rate delayed the days to tasselling and silking, while shortened the days to physiological maturity especially in 2018. The significantly shortest period to tasseling (47.5 days) and silking (50.0 days) while longest period to physiological maturity (102.7 days) under N3 treatment were recorded according to 2 years’ data. With increasing planting density, days to tasseling, silking and physiological maturity were delayed. The significantly longest period to tasseling (48.4 days), silking (51.2 days) and physiological maturity (102.9 days) under D3 treatment were recorded over two years.

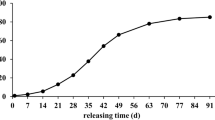

Dry matter accumulation

With the increase of either N rate or planting density, dry matter accumulation at 12-leaf stage, silking stage and physiological maturity stage were increased (Fig. 1). Compared to traditional N3 treatment, dry matter accumulation under N1 treatment showed a 11.6%, 12.2%, and 9.4% decrease in these three stages over 2 years. Compared to traditional D1 treatment, dry matter accumulation under D3 treatment showed a 16.8%, 28.4%, and 13.8% increase in these three stages over 2 years. The maximal dry matter accumulation was obtained with N3 × D3 treatment.

Dry matter accumulation of 12 leaf stage, silking stage and maturity stage in 2017 (left) and 2018 (right). The three N rates are 120 (N1), 180 (N2), and 240 (N3) kg ha−1. The three planting density levels are 60,000 (D1), 75,000 (D2), and 90,000 plants ha−1 (D3). Symbols represent means ± standard error. Vertical bars indicate standard error. Different letters within the same stage are significantly different at the 0.05 probability level.

Maize yield and profit

N rate had significant effects on 1000-grain weight, grain yield and profit and didn’t have significant effects on ear number and grains per ear, and planting density had significant effects on all these five indices (Table 2). Increasing N rate caused 1000-grain weight, grain yield and profit increases with the peak showing at N2 treatment and remained stable at traditional N3 treatment. After averaging the effects of planting density, compared to N1 treatment, traditional N3 treatment increased 1000-grain weight, grain yield and profit by 2.6%, 5.3% and 2.7%, respectively. Increasing planting density resulted in an increased ear number, a decreased grains per ear and 1000-grain weight, an increased initially and then stable yield and profit. After averaging the effects of N rate, ear number, grains per ear, 1000-grain weight, grain yield and profit of D3 treatment were 39.2%, − 8.7%, − 7.2%, 16.6% and 16.2% higher than the traditional D1 treatment, respectively. According to the 2 years’ results, the greatest grain yield and profit was easily obtained for the combination of N2 or N3 and D2 or D3.

N uptake and N efficiency indices

Significant effects were observed from N rate and planting density on total N uptake, PFPN and NER. As N rate increased, the total N uptake was increased, while PFPN and NER were decreased. Traditional N3 treatment led to the maximal total N uptake and the minimal in PFPN and NER at all planting densities. Planting density had a different effect on these three indices. With the increased planting density, the total N uptake was increased, while PFPN was increased at D2 treatment and then kept stable at D3 treatment, NRE was kept stable at D2 treatment and then decreased at D3 treatment. Based on the 2 years’ results, the high PFPN and NER were obtained at the combination of low N application and suitable planting density.

Optimizing N application rate and planting density

To determine the optimal N application rate and planting density for profit, the relationships between N application and planting density and the profit was analysed (Fig. 2). The response surfaces that demonstrating the combined effect of N application and planting density on the profit were convex. Namely, with the increased N application and planting density, the profit was firstly increased, then reached a peak value, and finally decreased.

Quadratic polynomial trend surface fitting of profit, N application rate, and planting density. x was set as N application rate, y was set as planting density, and z was set as profit to show the effects of N application rate and planting density on the profits of 2017 (up) and 2018 (middle) and 2 years’ mean (down).

According to the second-order polynomials in Table 3, the predicted maximum profit was 3012 $ ha−1 (199 kg ha−1 and 81,081 plants ha−1) in 2017 and 2774 $ ha−1 (205 kg ha−1 and 84,782 plants ha−1) in 2018. Based on the above combination of N rate and planting density, the grain yield (MaxProfit GY), PFPN (MaxProfit PFPN) and NER (MaxProfit NER) were 12.1 t ha−1, 60.9 kg kg−1 and 41.1% in 2017, 11.3 t ha−1, 54.7 kg kg−1 and 38.6% in 2018. Compared to the traditional N3D1 treatment, MaxProfit GY, MaxProfit PFPN and MaxProfit NER were increased by 17.6%, 39.8% and 3.6% in these 2 years, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, the plants at high planting density took longer time to tasseling, silking, and physiological maturity than the plants at low planting density. This indicated that dense planting may have slowed down plant development owing to more competition between plants16. A similar result was reported in earlier studies as dense population induced lengthening of the time to phenological characteristics17,18,19. In this study, increase in N input induced the advance in days to tasseling and silking. It may be due to quick growth under high nitrogen level. However, the plants took more time to physiological maturity with the increasing rate of N application. Namely, increasing N rate delayed the reproductive growth period of maize. It could be because the plants with more N application were remained green for longer period, which caused longer maturity period. The result was consistent with that of Shresth et al.18. The longer maturity period under high N and planting density conditions could be conducive to the increase of grain yield.

In our study, high N input or high planting density enhances the dry matter accumulation and grain yield. There was a significant positive correlation between the dry matter and the grain yield20. Furthermore, grain yield was extremely affected by the assimilate allocation balance between vegetative and reproductive organs11,21,22. The longer reproductive growth period and more photosynthates availability with high N application induced the greater assimilates allocation to the seeds during grain filling, which improved grains per ear and grain weight. Increased plant density induced leaf senescence of lower leaf and then decreased the biomass accumulation, resulting in a lower yield per plant23. Also, greater inter-plant competition for light, water and nutrients with excessive planting density increased ear tip-barrenness which decreased grains per ear and grain weight. Yield improvement in response to higher density might be owing to maximize light interception during the vital period for grain set24. At the same time, the increased ear number per ha resulted from excessive density might offset the decrease of grains per ear and grain weight. These can be the reasons for the stable yield between D3 treatment and D2 treatment. Under high planting density, a moderate decrease of leaf source through leaf removal enhanced photosynthetic performance and improved the post-silking dry matter accumulation and harvest index, and thus the grain yield25,26. This indicates that grain yield at high density could achieve further improvement through optimal management practices. In this study, N3D3 obtained 16.1% higher grain yield than the traditional N3D1, a great yield increase of summer maize in smallholder fields in Huanghuaihai region of China.

According to the former results20,27,28, the dry matter was the driving force of the enhanced N uptake. In this study, the increases both N application rate and planting density improve the dry matter accumulation, which causes a high N absorption and assimilation level. Therefore, the increased N input or planting density maintained a high N uptake. In this study, PFPN and NER decreased with increased N rate. This is similar to the results of previous studies12,15. PFPN and NER were found to have a different change with planting density, and the medium D2 density had higher PFPN and NER than the low D1 density and high D3 density. This indicates that extremely high planting density is not helpful for the increase of PFPN and NER. This result is consistent with that of Zhang et al.12 and can possibly be explained by the fact that excessive planting density results in a non-significant yield increase because of competition between plants and much more total N uptake.

Nutrient competition, mainly with respect to N, can be intensified by the increased planting density. In this study, a significant interaction between N application and planting density (Tables 2, 4) is observed. Therefore, it should be possible to optimize N application and planting density to regulate a trade-off between the three yield components (ear number, grains per ear and 1000-grain weight) to achieve high profit and N use. According to the two years’ results in this study, when the predicted maximal profit of 2890 dollar ha−1 was achieved, N application rate and planting density were 201 kg ha−1 and 82,680 plants ha−1, respectively. The yield, PFPN and NER under this condition were higher than the traditional N3D1 treatment. Therefore, reduced N application rate and increased planting density improved not only the profit but also grain yield, PFPN and NER for smallholder farming in Huanghuaihai region. Also, this study provides an important reference for determining the optimal combination of N application rate and planting density to obtain the highest profit under certain ecological conditions.

Conclusions

Maize profit and nitrogen use were affected by N application and planting density. Compared to traditional practices, the combination of 37.8% increase in planting density and 16.3% reduction in N application achieved the maximal profit. Under this optimal combination, increases of 17.6% for grain yield, 39.8% for PEPN, 3.6% for NRE were achieved than the traditional practices. Therefore, an appropriate increase of planting density and a reasonable reduction of N application can enhance profit, increase grain yield, reduce fertilizer input, and enhance nitrogen use of summer maize in Huanghuaihai region of China.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

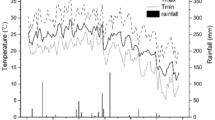

Field experiments were conducted in 2017 and 2018, in Haiyang County (36° 78′ N, 121°16′ E), Shandong Province, China. The soil was classified as Fluvo-aquic soil. The site was characterized by fine-textured clay loam and well drained. The previously grown crop was wheat in 2017 and 2018. The nutrient status in the top 0–20 cm arable soil layer before seeding consisted of 21.84 g kg−1 organic matter (Walkley and Black method), 1.08 g kg−1 total N (Kjeldahl method), 41.74 mg kg−1 available P (Olsen method), 111.64 mg kg−1 available K (Dirks-Scheffer method). Soil pH was 5.44 as determined by acidity meter. The contents of sand, silt and clay were 470, 290, 240 g kg−1, respectively. Particle-size was analyzed using the hydrometer method after organic matter oxidation29. Precipitation and air temperature were measured by an automatic weather station (Fig. 3).

Experimental design and field management

The field experimental treatments were arranged in a split plot design with three replications. According to our survey and the present study15,30,31, traditional nitrogen rate and planting density in smallholder fields in Huanghuaihai region in China were about 240 kg ha−1 and 60,000 plants ha−1, respectively. Based on these, the main plots were assigned to three N application rates (N1: 120 kg ha−1; N2: 180 kg ha−1 and N3: 240 kg ha−1), and subplots were designed to three planting densities (D1: 60,000 plants ha−1; D2: 75,000 plants ha−1 and D3: 90,000 plants ha−1). Every plot comprised of ten rows, 0.6 m spacing between rows and 8 m long. The plants in the rows were spaced at 0.278, 0.222, and 0.185 m, corresponding to 60,000, 75,000, and 90,000 plants ha−1, respectively. For the three N treatments, one half of the assigned amount, 60, 90, and 120 kg ha−1 (urea, N 46%) was applied as a basal fertilizer before sowing and the other half was applied at jointing stage. For all treatments, 80 kg phosphate (superphosphate, P2O5 12%) and 160 kg potassium (potassium sulfate, K2O 50%) fertilizers were applied as a basal fertilizer.

Zhengdan 958, a widely released maize hybrid in Huanghuaihai region in China, was used. Zhengdan 958 was the offspring of inbred Zheng 58 and Chang 7-2 (deposition number 20000009), which are approved in China. In this study, the seeds of Zhengdan 958 were provided by Beijing Denong Seed Technology Co. Ltd. Experimental research and field studies on plants complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. Seeds were sown by hand, width two seeds per hole, on 22 June 2017 and 30 June 2018, respectively. The maize plants were thinned to one plant per hole to keep the designed densities one week after emergence. Crop management was the same as the local maize field. Maize was harvested on 9 October 2017 and 15 October 2018.

Sampling and measurements

The dates on which about 75% plants were at tasseling stage and silking stage were recorded. Physiological maturity was judged by the appearance of seed black layer. Days to tasseling, silking and physiological maturity were counted as the days from emergence date to tasseling date, silking date and physiological maturity date, respectively.

At 12-leaf, silking and physiological maturity, five whole plants were sampled to dry to a constant weight and determine dry matter. At physiological maturity, maize ears were collected from the middle two rows per plot to measure grain number per ear and 1000-grain weight. Finally, maize ears were harvested from central area of 14.4 m2 per plot to measure ear number and grain yield. Profit was estimated using the following equation according to the method of Han et al.20.

where the average price of maize grain, urea N, and maize seed in 2017 and 2018 was 269 $ t−1, 0.651 $ (kg urea-N)−1, and 1.5 $ (1000-seed)−1, respectively.

The whole plant of physiological maturity was divided to stalks, leaves, cob, and grain. The samples were dried, weighed, ground and digested with H2SO4–H2O2. N concentration was measured with the semi-micro Kjedahl method32. N uptake was estimated by multiplying the N concentration by the dry weight. PFPN and NER were calculated as follows.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using DPS 7.05. Analysis of variance was conducted to evaluate the effects of N rate and planting density on the response variables. Means were compared using LSD test and differences were regarded as significance at P < 0.05. The trend surface simulation was analyzed using SPSS 19.0. Graphs were plotted using Matlab R2018a and OriginPro 9.0.

References

Stewart, W. M., Dibb, D. W., Johnston, A. E. & Smyth, T. J. The contribution of commercial fertilizer nutrients to food production. Agron. J. 97, 1–6 (2005).

Stewart, W. M. & Roberts, T. L. Food security and the role of fertilizer in supporting it. Procedia Eng. 46, 76–82 (2012).

Ahmed, M., Rauf, M., Mukhtar, Z. & Saeed, N. A. Excessive use of nitrogenous fertilizers: An unawareness causing serious threats to environment and human health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 26983–26987 (2017).

Davies, B., Coulter, J. A. & Pagliari, P. H. Timing and rate of nitrogen fertilization influence maize yield and nitrogen use efficiency. PLoS ONE 15(5), e0233674 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Improving grain yield and protein concentration of maize (Zea mays L.) simultaneously by appropriate hybrid selection and nitrogen management. Field Crops Res. 249, 107754 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Factors affecting nitrogen use efficiency and grain yield of summer maize on smallholder farms in the North China Plain. Sustainability 10, 363 (2018).

Gou, L., Xue, J., Qi, B., Ma, B. & Zhang, W. Morphological variation of maize cultivars in response to elevated plant densities. Agron. J. 109, 1444–1453 (2017).

Yang, Y. et al. Improving maize grain yield by matching maize growth and solar radiation. Sci. Rep. 9, 3635 (2019).

Zhai, L. C., Xie, R. Z., Ming, B., Li, S. K. & Ma, D. L. Evaluation and analysis of intraspecific competition in maize: A case study on plant density experiment. J. Integr. Agric. 17, 2235–2244 (2018).

Wei, S., Wang, X., Zhu, Q., Jiang, D. & Dong, S. Optimising yield and resource utilisation of summer maize under the conditions of increasing density and reducing nitrogen fertilization. Sci. Nat. 104, 86 (2017).

Wei, S., Wang, X., Li, G., Jiang, D. & Dong, S. Maize canopy apparent photosynthesis and 13C-photosynthate reallocation in response to different density and N rate combinations. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1113 (2019).

Zhang, G. et al. Optimizing planting density to improve nitrogen use of super high-yield maize. Agron. J. 112, 1–12 (2020).

Hou, P. et al. How to increase maize production without extra nitrogen input. Resour. Conserv. Recyc. 160, 104913 (2020).

Zhou, B. et al. Integrated agronomic practice increases maize grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency under various soil fertility conditions. Crop J. 7, 527–538 (2019).

Jin, L. et al. Effects of integrated agronomic management practices on yield and nitrogen efficiency of summer maize in North China. Field Crops Res. 134, 30–35 (2012).

Hamidi, A. & Nasab, A. The effect of various plant density and nitrogen use levels on phenology of two medium-maturity corn (Zea mays L.) hybrids. Iran. J. Agric. Sci. 32(4), 857–874 (2001).

Amanullah, Khattak, R. A. & Khalil, S. K. Plant density and nitrogen effects on maize phenology and grain yield. J. Plant Nutr. 32, 246–260 (2009).

Shrestha, J., Yadav, D. N., Amgain, L. P. & Sharma, J. P. Effects of nitrogen and plant density on maize (Zea mays L.) phenology and grain yield. Curr. Agric. Res. 6(2), 175–182 (2018).

Zhang, M. et al. How plant density affects maize spike differentiation, kernel set, and grain yield formation in Northeast China? J. Integr. Agric. 17(8), 1745–1757 (2018).

Han, K., Yin, F. & Liu, P. Planting density and N application rate balance maize agronomic and environmental effect. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 117, 337–349 (2020).

Ciampitti, I. A. & Vyn, T. J. A comprehensive study of plant density consequences on nitrogen uptake dynamics of maize plants from vegetative to reproductive stage. Field Crops Res. 121, 2–18 (2011).

Yan, P. et al. Interaction between plant density and nitrogen management strategy in improving maize grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency on the North China Plain. J. Agric. Sci. 154, 978–988 (2015).

Li, R., Liu, P., Dong, S., Zhang, J. & Zhao, B. Increased maize plant population induced leaf senescence, suppressed root growth, nitrogen uptake, and grain yield. Agron. J. 111(4), 1581–1591 (2019).

Andrade, F. H., Calviño, P., Cirilo, A. & Barbieri, P. Yield responses to narrow rows depend on increased radiation interception. Agron. J. 94, 975–980 (2002).

Liu, T. et al. Optimum leaf removal increases canopy apparent photosynthesis, 13C-photosynthate distribution and grain yield of maize crops grown at high density. Field Crops Res. 170, 32–39 (2015).

Cao, Y. J., Wang, L. C., Gu, W. R., Wang, Y. J. & Zhang, J. H. Increasing photosynthetic performance and post-silking N uptake by moderate decreasing leaf source of maize under high planting density. J. Integr. Agric. 20, 494–510 (2021).

Shi, D. et al. Increased plant density and reduced N rate lead to more grain yield and higher resource utilization in summer maize. J. Integr. Agric. 15(11), 2515–2528 (2016).

Qiang, S. et al. Maize yield, rainwater and nitrogen use efficiency as affected by maize genotypes and nitrogen rates on the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manage. 213, 996–1003 (2019).

Sheldrick, B. H. & Wang, C. Particle size distribution. In Soil Sampling and Methods of Soil Analysis (ed. Carter, M. R.) 499–511 (Lewis, 1993).

Du, X., Wang, Z., Lei, W. & Kong, L. Increased planting density combined with reduced nitrogen rate to achieve high yield in maize. Sci. Rep. 11, 358 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. The effects of one-off fertilization of summer maize in Huanghuaihai region. Sci. Agric. Sin. 51(20), 3909–3919 (2018).

Monteith, J. L. & Unsworth, M. H. Principles of Environmental Physics 2nd edn. (Eaward Arnold, 1990).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0300306) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671621) and Shandong Program for Improved Varieties of Agriculture (2021LZGC022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Y.Z. and J.Z.Y. designed the experiment. H.Y.Z., C.R.Z., P.S. & G.H.X. performed the experiments. H.Y.Z., C.R.Z., X.W.J. and J.Z.Y. analyzed the data and performed the statistical analyses. H.Y.Z. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhang, C., Sun, P. et al. Optimizing planting density and nitrogen application to enhance profit and nitrogen use of summer maize in Huanghuaihai region of China. Sci Rep 12, 2704 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06059-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06059-0