Abstract

Carbonatites host some unique ore deposits, especially REE, and fractional crystallization might be a potentially powerful mechanism for control enrichment of carbonatitic magmas by these metals to economically significant levels. At present, data on distribution coefficients of REE during fractional crystallization of carbonatitic melts at volcanic conditions are extremely scarce. Here we present an experimental study of REE partitioning between carbonatitic melts and calcite in the system CaCO3-Na2CO3 with varying amounts of P2O5, F, Cl, SiO2, SO3 at 650–900 °C and 100 MPa using cold-seal pressure vessels and LA-ICP-MS. The presence of phosphorus in the system generally increases the distribution coefficients but its effect decreases with increasing concentration. The temperature factor is high: at 770–900 °C DREE ≥ 1, while at lower temperatures DREE become below unity. Silicon also promotes the fractionation of REE into calcite, while sulfur contributes to retention of REE in the melt. Our results imply that calcite may impose significant control upon REE fractionation at the early stages of crystallization of carbonatitic magmas and might be a closest proxy for monitoring the REE content in initial melt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbonatites are rare carbonate-dominated magmatic rocks that, in some cases, host economically significant deposits of REE and Nb, which are important for modern high-tech and “green” industry. More than 527 carbonatite occurrences have been recorded in the world so far1. However, only about 30 mineralized carbonatites host economic resources of REE2,3. The scientific and practical interest in carbonatites is great, but the processes of carbonatite formation and ore-grade enrichments of REE and Nb are far from being fully understood. Researchers identify the following mechanisms of carbonatite formation: (1) primary origin of carbonatitic magmas by partial melting of a carbonated mantle source4–15; (2) derivative origin from an homogeneous alkaline silicate magma by silicate-carbonate liquid immiscibility16,17; (3) derivative origin by extensive fractional crystallization of a carbonated silicate parental liquid18,19; (4) melting of oceanic sediments and material of the subducting plate, sublithospheric mantle and upper plate20,21.

Identification of exact processes responsible for the formation of carbonatitic magmas is hampered by widespread Na–K metasomatism (fenitization) associated with carbonatites, which manifests the loss of alkalis and volatiles from their parental magmas22. In addition, many (if not most) intrusive carbonatites are cumulates, dominated by calcite or dolomite, differing in composition from their parental magma23 and often affected by extensive textural and chemical re-equilibration after emplacement24.

As seen from experiments14,25,26,27, direct smelting from the mantle source and silicate-carbonate immiscibility are unable to provide concentration of REE to economically significant levels. Immiscibility experiments in various silicate–carbonate systems have demonstrated that Pb, Nb, Th, U and most of the REE preferentially partition into the silicate liquid, whereas Sr, Ba and F partition into the conjugate liquid carbonate phase25,26,28. This pattern of element partitioning is inconsistent with a high content of primary LREE- and HFSE-rich minerals in carbonatites: fluorapatite, fluorcarbonates, monazite, pyrochlore, etc. Thus, another evolutionary mechanism is needed for the enrichment of carbonatitic magmas in REE and HFSE, and fractional crystallization might be powerful driver for it.

The majority of experimental estimates of partition coefficients for REE have been obtained for main rock-forming minerals (olivine, pyroxene, garnet, amphibole and biotite), and some accessory minerals (such as rutile, apatite, perovskite, and baddeleyite) at P–T conditions of the upper mantle27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Experimental constraints on REE partitioning in carbonatitic magmas at crustal pressures are sparse. Because of low crystallization temperature and low viscosity of carbonatitic magmas, fractional crystallization can proceed in them up to shallow depths and control the distribution of REE and HFSE, leading to the formation of a deposit or a barren carbonatite body. Therefore, it is important to assess the effect of fractional crystallization at crustal conditions and to identify the influencing factors.

Carbonate minerals are the principal constituents of intrusive carbonatites: their content ranges from 50 modal %, which is accepted as a nominal threshold for this rock type40, to well over 90% in some varieties interpreted as cumulates23. Considering the high propensity of calcite to various postmagmatic changes, plasticity and recrystallization, observed trace element contents may be far from the original magmatic pattern. Hence, experimental modelling of trace element distribution between calcite and carbonatite melt at magmatic conditions is important.

Additional ligands such as F−, OH−, Cl−, SO42− and PO43− are likely to have strong effects upon the REE partitioning. In our previous work41 we carried out a pilot series of experiments to obtain distribution coefficients for REE and HFSE between calcite, fluorite and nominally dry carbonatitic melts in synthetic compositions with CaO at 37–54 wt.%, Na2O 7–24 wt.%, F 5–9 wt.%, P2O5 between 0 and 9.5 wt.% at 650–900 °C and 100 MPa. The distribution coefficients for individual REE in calcite in that study did not exceed 0.1 and in fluorite they were below 0.25. Total REE concentrations in calcites were at about 500–700 ppm. Such concentrations are normal for primary igneous calcites in carbonatites42. However, there are described primary igneous calcites with REE contents at 1400–2000 ppm (e.g., the Aley complex, Canada42). This study is aimed at a more detailed assessment of the effects of melt composition, and especially the concentrations of P2O5, SiO2 and SO3 components on the REE distribution between calcite and melt at 900–650 °C and 100 Mpa (Table 1).

Results

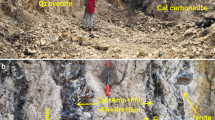

Carbonatitic melts in all the experiments quenched as aggregates of fine-grained dendritic crystals with abundant fluid bubbles probably dominated by CO2 (Fig. 1, 2; Tables 2, 3). In phosphate-bearing samples, quenched melt is full of needle-shaped crystals of quench Ca-phosphate, presumably apatite (Figs. 1a, Fig. 2a–c). In experiments with SiO2 fine crystals of wollastonite and Zr-Hf-silicate (zircon-hafnon) are also formed (Fig. 2d; Table 2). Oxides of HFSE and REE in all samples form aggregates of fine crystals with complex composition (baddeleyite, perovskite-lueshite solid solutions and crystals of pyrochlore supergroup) (Fig. 2a–c). The crystals are few microns in size and are not suitable for representative analyzes by microprobe or LA-ICP-MS. Rounded, irregularly shaped, drop-like fluorite crystals are formed in samples with high content of F (Fig. 2a; Table 2).

Calcite has various morphology: rhombohedral or prismatic (Fig. 1a, 2a), amorphous (Fig. 1b), needle-like (Fig. 1d,f) and tabular rounded crystals (laths) up to 250 µm in most experiments (Figs. 1c,e, 2c), which are typical for early generations of calcite in carbonatites43. The amount of calcite crystals in some samples is so high that they form a crystal mush at the bottom of the samples (Fig. 1c,e). Calcite major element composition is close to stoichiometric (Table 3).

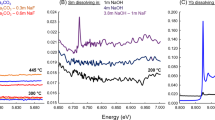

Trace element composition of the run products presented in Table 4. Partition coefficients were calculated according to the Nernst formula as mass ratios of element content in a crystalline phase to its content in the melt: DElement = CCrystal/CMelt (Table 5). DSr is > 1 for all samples (Fig. 3). In all experiments DSr >> DREE, except NCPSi mixtures. Almost all DREE plots show a positive Eu and Y anomalies. In general, the slope of the DREE plots is positive, with the exception of NCPSi samples.

DREE of calcites, published in our previous work41, are close to zero: 0.02–0.04 in NCF samples and 0.04–0.1 in sample with NCFP-6. In experiments with the NCFP mixtures, presented in this work, the averages of DREE are much higher: 0.1–0.2 and 0.52–1.39 (Fig. 3a). The averages of DREE in NCP samples vary in 0.55–1.4, but taking into account the analytical uncertainty for each individual element, it is almost the same (Fig. 3b). In experiments at highest temperatures the highest DREE are observed for both mixtures.

NCPSi samples demonstrate highest DREE with large variations (Fig. 3c). #7 NCPSi-1 sample demonstrates the highest DREE among them, while DREE of #10 NCPSi-2 and #12 NCPSi-3 is almost equal. This is probably directly related to the content of SiO2 and P2O5 in the samples.

The graphs of DREE of NCPS samples are almost flat, with a slight positive slope. The average DLREE in #5 NCPS-1 vary in 1.2–1.7 with strong Eu anomaly, while the coefficients of other elements are about 1.2 and almost equal with #11 NCPS-2.

Discussion

Factors influencing the partitioning of REE into calcite in carbonatite systems

As seen from natural carbonatite samples, the early generations of calcites are characterized by increased content of cations, which size doesn’t allow stoichiometrically replace Ca2+ at crustal conditions: Mg, Sr, Ba are most abundant among them43,44. Sometimes it leads to formation of Ca-Ba-Sr “protocarbonates”, which are unstable and decay into calcite and baritocalcite in the form of a solid solution. Consequently, elevated temperatures favor the entry of cations, whose size precludes their unlimited substitution for Ca2+. Along with these cations, REE may also enter the structure of calcite, which is also noted in natural samples: for example, the positive correlation between Ba, Pb, and LREE in early calcites of the Aley complex (Canada)42,43. The strong effect of temperature is confirmed by our experiments: in most experiments DREE > 1 at high temperatures (900–820 °C), while it is about unity or less at lower temperatures41.

As follows from a comparison with our previous experiments41, the presence of small amounts of phosphorus may be another positive and key factor for the fractionation of REE into calcite in carbonatite systems with high Na2O content. The presence SiO2 in small amounts in the system may be another powerful driver for incorporating DREE into calcite. Sulfur, on the contrary, may promotes the dissolution (retention) of REE in the melt. However, to evaluate the total effect of these and other parameters (such as F, Cl) additional experiments are required.

Calcite as a monitor of REE

Our data show that, under the combination of some factors at the magmatic stage of evolution of carbonatite magma, calcite can retain a significant gross budget of REE and may be a closest proxy for estimation of initial REE content in the melt. For example, at high temperatures, in local areas of a carbonatite body, or when there is a lack of material for fractionation of early traditional mineral concentrators of a large amount of REE (such as apatite, monazite, etc.) even at low concentration of REE in the melt.

High susceptibility of calcite to postmagmatic changes, plasticity and recrystallization creates the possibility of releasing from calcite large bulk amounts of REE, Sr and Ba and their subsequent redeposition as a result of interaction with later melts or solutions or as a result of metamorphism. According to various estimates42,43, such processes can occur at shallow depths already at temperatures of 400–600 and even 730 °C, which can lead to active loss of REE by calcite, overprinting his textures, and transfer and redeposition of REE far from it due to weakening of the carbonatite body by porous fluids. These events can also be aggravated by recrystallization of calcite during plastic deformation under a stress conditions.

Patterns of such phenomena occur, for example, in calcites from Afrikanda and Murun carbonatites (Russia) and Bearpaw Mts (USA)43: diffusion-induced zoning in primary calcite involving a decrease in Mn, Sr , Ba and REE along grain boundaries and fractures; the Sr and REE released from calcite are precipitated interstitially as strontianite, baritocalcite, Ba-Sr-Ca-carbonates, barite, burbankite and ancylite.

Methods

Experimental mixtures were composed of reagent-grade CaCO3, Na2CO3, Ca3(PO4)2, CaF2, Na2Si2O5 and Na2SO4 and doped with mixtures of trace elements: Zr, Hf, Nb, Ta, Ti, Sr, W, Mo (HFSE mixture) and all REE, including Sr and Y (REE mixture) (Table 1). Both mixtures of trace elements were composed of equal weight proportions of reagent-grade CeF2, SrCO3 and pure oxides of other individual elements. Pure reagents were dried at 180 °C overnight, mixed under acetone in agate mortar and dried again. The mixtures of NCFP type are direct analogues of our mixtures, used in previous work41. About 45–55 mg starting mixtures were put in gold capsules and sealed by arc-welding in the flow of Ar.

Experiments were performed at pressure of 100 MPa and temperature range of 650–900 °C in rapid-quench cold-seal pressure vessels at the German Research Centre for Geosciences (GFZ Potsdam). The temperature range is close to the parameters for nature cooling systems of carbonatitic melts. A detailed description of this type of the vessels described in45. The autoclaves at GFZ Potsdam are made of the Ni–Cr alloy Vakumelt ATS 290-G (ThyssenKrupp AG). Oxygen fugacity was not controlled, but believed to have been close to that of the Ni–NiO equilibrium, buffered by oxidation reactions of water, used as pressure medium, and the Ni–Cr alloy of the autoclave. Temperature measured by external Ni–CrNi thermocouple, calibrated against the melting temperature of gold. Temperature measurements are corrected for a temperature gradient inside the autoclaves, which was measured using a second inner thermocouple during the initial calibration of the vessels. The external thermocouple has an uncertainty of approximately ± 1 °C, and the total uncertainty of temperature measurements, including the uncertainties due to the temperature gradients, is estimated to be ± 5 °C. Pressure is measured by transducers, and results were checked against a pressure gauge. The transducers and gauge are factory calibrated and have an accuracy of better than ± 0.1 MPa. Run times varied from 20 to 141 h. In experiments with decreasing temperature, the temperature lowered gradually, with decrease of 5–7 °C in every 1–1.5 h. Samples were kept for at least 10 h at the final temperature before quenching. The quenching of the experimental samples in such apparatus is isobaric and less than a second.

After the experiments, samples were mounted in epoxy resin and polished with diamond polishing pastes without water to avoid dissolution of alkalis. Major components of the run products were analyzed using Cameca SX-50 and SX-100 electron microprobes in the GFZ Potsdam and energy-dispersive spectrometry (EDS) in combination with back-scattered electron imaging (BSE) using a MIRA 3 LMU SEM (TESCAN Ltd.) equipped with an INCA Energy 450 XMax 80 microanalysis system (Oxford Instruments Ltd.) in the Analytical Center for multi-elemental and isotope research SB RAS (Novosibirsk, Russia).

Microprobe analyses were performed in WDS mode with a 10 nA beam current and accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Counting time for F (analyzed with TAP crystal) was 40 s. For all other elements it was set to 20 s on peak and 10 s on background. These parameters are benign to avoid any damage to carbonates or melt. The following synthetic and natural standards were used for the calibration: wollastonite (Ca), albite and jadeite (Na), apatite (P), LiF (F). Quenched melts were analyzed with a defocused beam (beam diameter of 20–40 µm). At least five point analyses were performed on each phase to obtain statistically representative averages.

For EDS analyses the samples were coated with a 25 µm conductive carbon coating. EDS analyses were made at low vacuum of 60–80 Pa, an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, a probe current of 1 nA, and accumulation time of 20 s. The simple compounds and metals were used as reference samples for most of the elements: SiO2 (Si-Kα and O-Kα), diopside (Ca-Kα), albite (Na-Kα), Ca2P2O7 (P-Kα), BaF2 (F-Kα), pyrite (S-Kα), SrF2 (Sr-Kα) and various (LREE)PO4 (LREE-Lα). Correction for matrix effects was made by the XPP algorithm, implemented in the software of the microanalysis system. Metallic Co served for quantitative optimization (normalization to probe current and energy calibration of the spectrometer).

Trace elements were measured by LA-ICP-QQQ-MS applying a Geolas Compex Pro 193 nm excimer laser coupled to a Thermo iCAP TQ mass spectrometer in the GFZ Potsdam. Analytical conditions comprised a spot size of 24 µm, repetition rate of 8 Hz, and laser energy density of 5 J cm−2. NIST SRM 610 was used as external standard and Ca as derived from EPMA as internal standard. BCR-2G was analyzed as the validation material known-unknown for accuracy control and its trace element concentrations are in agreement with published reference datavalues at < 10% 2σ RSD. Each analysis comprised 20 s background, 40 s ablation and 20 s wash-out. Data was processed using the trace elements IS data reduction scheme46 in iolite 3.6347.

Experimental experience gained with carbonatite systems under these conditions by us and by other researchers shows that the chosen duration of experiments is sufficient to achieve equilibrium in experiments with synthetic carbonatites due to the high rate of kinetic processes in them, especially with small experimental samples. Moreover, most of the duration of the experiments (from tens of hours to days) took place at the final temperature of the experiments to achieve equilibrium before quenching. During the subsequent analysis of the samples both by scanning microscopy and LA-ICP-MS, we did not find any zoning in the content of either the main components or rare elements in the center and on the periphery of the crystal phases.

References

Woolley, A.R. Kjarsgaard, B.A. Carbonatite occurrences of the world: map and database. Geol. Surv. of Canada. 28 pages (1 sheet), 1 CD-ROM, https://doi.org/10.4095/225115 (2008).

Verplanck, P. L., Mariano, A. N. & Mariano, A. Rare earth ore geology of carbonatites. In Rare Earth and Critical Elements in Ore Deposits (eds Verplanck, P. L. & Hitzman, M. W.) 5–32 (Society of Economic Geologists, Littleton, 2016).

Woolley, A. R. & Kjarsgaard, B. A. Paragentic types of carbonatite as indicated by the diversity and relative abundances of associated silica rocks: evidence from a global database. Can. Mineral. 46, 741–752 (2008).

Wyllie, P. J. & Huang, W. L. Carbonation and melting reactions in the system CaO–MgO–SiO2–CO2 at mantle pressures with geophysical and petrological applitations. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 54, 79–107 (2008).

Wallace, M. E. & Green, D. H. An experimental determination of primary carbonatite magma composition. Nature 335, 343–346 (1988).

Falloon, T. J. & Green, D. H. The solidus of carbonated, fertile peridotite. Earth Planet. Sci. Let. 94, 364–370 (1989).

Falloon, T. J. & Green, D. H. The solidus of carbonated fertile peridotite under fluid-saturated conditions. Geology 18, 195–199 (1990).

Dalton, J. A. & Presnall, D. C. Carbonatitic melts along the solidus of model lherzolite in the system CaO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–CO2 from 3 to 7 GPa. Contrib. Min. Petr. 131, 123–135 (1998).

Dalton, J. A. & Presnall, D. C. The continuum of primary carbonatitic-kimberlitic melt compositions in equilibrium with lherzolite: data from the system CaO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–CO2 at 6 GPa. J. Petrol. 39, 1953–1964 (1998).

Gudfinnsson, G. H. & Presnall, D. C. Continuous gradation among primary carbonatitic, kimberlitic, melilititic, basaltic, picritic, and komatiitic melts in equilibrium with garnet lherzolite at 3–8 GPa. J. Petrol. 46, 1645–1659 (2005).

Dasgupta, R. & Hirschmann, M. M. Melting in the Earth’s deep upper mantle caused by carbon dioxide. Nature 440, 659–662 (2006).

Dasgupta, R. & Hirschmann, M. M. Effect of variable carbonate concentration on the solidus of mantle peridotite. Am. Min. 92, 370–379 (2007).

Brey, G. P., Bulatov, V. K., Girnis, A. V. & Lahaye, Y. Experimental melting of carbonated peridotite at 6–10 GPa. J. Petrol. 49, 797–821 (2008).

Foley, S. F. et al. The composition of near-solidus melts of peridotite in the presence of CO2 and H2O between 40 and 60 kbar. Lithos 112, 274–283 (2009).

Brey, G. P., Bulatov, V. K. & Girnis, A. V. Melting of K-rich carbonated peridotite at 6–10 GPa and the stability of K-phases in the upper mantle. Chem. Geol. 281, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.12.019 (2011).

Kjarsgaard, B.A., Hamilton, D.L. The genesis of carbonatites by immiscibility. In Carbonatites: Genesis and Evolution. London. 388–404 (1989).

Lee, W. & Wyllie, P. J. Experimental data bearing on liquid immiscibility, crystal fractionation and the origin of calciocarbonatites and natrocarbonatites. Int. Geol. Rev. 36, 797–819 (1994).

Otto, J. W. & Wyllie, P. J. Relationship between silicate melts and carbonate-precipitating melts in CaO–MgO–SiO2–CO2–H2O at 2 kbar. Miner. Petrol. 48, 343–365 (1993).

Veksler, I. V., Nielsen, T. F. D. & Sokolov, S. V. Mineralogy of crystallized melt inclusions from Gardiner and Kovdor ultramafic alkaline complexes: Implications for carbonatite genesis. J. Petrol. 39, 2015–2031 (1998).

Hou, Z. Q. et al. The Himalayan collision zone carbonatites in western Sichuan, SW China: Petrogenesis, mantle source and tectonic implication. Earth Planet Sci Lett 244, 234–250 (2006).

Hou, Z., Liu, Y., Tian, S., Yang, Z. & Xie, Y. Formation of carbonatite-related giant rare-earth-element deposits by the recycling of marine sediments. Sci. Rep. 5, 10231 (2015).

Le Bas, M. J. Diversification of carbonatite. In Carbonatites: Genesis and Evolution (ed. Bell, K.) 428–445 (Unwin Hyman, 1989).

Xu, C. et al. Flat rare earth element patterns as an indicator of cumulate processes in the Lesser Qinling carbonatites, China. Lithos 95, 267–278 (2007).

Chakhmouradian, A. R., Mumin, A. H., Demeny, A. & Elliott, B. Postorogenic carbonatites at Eden Lake, Trans-Hudson Orogen (northern Manitoba, Canada). Lithos 103, 503–526 (2008).

Veksler, I. V., Petibon, C., Jenner, G., Dorfman, A. M. & Dingwell, D. B. Trace element partitioning in immiscible silicate and carbonate liquid systems: An initial experimental study using a centrifuge autoclave. J. Petrol. 39, 2095–2104 (1998).

Veksler, I. V. et al. Partitioning of elements between silicate melt and immiscible fluoride, chloride, carbonate, phosphate and sulfate melts with implications to the origin of natrocarbonatite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 79, 20–40 (2012).

Dasgupta, R., Hirschmann, M. M., McDonough, W. F., Spiegelman, M. & Withers, A. C. Trace element partitioning between garnet lherzolite and carbonatite at 6.6 and 8.6 GPa with applications to the geochemistry of the mantle and of mantle-derived melts. Chem. Geol. 262, 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.02.004 (2009).

Jones, J. H., Walker, D., Picket, D. A., Murrel, M. T. & Beate, P. Experimental investigations of the partitioning of Nb, Mo, Ba, Ce, Pb, Ra, Th, Pa and U between immiscible carbonate and silicate liquids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 59, 1307–1320 (1995).

Prowatke, S. & Klemme, S. Rare earth element partitioning between titanite and silicate melts: Henry’s law revisited. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 70, 4997–5012 (2006).

Blundy, J. & Dalton, J. Experimental comparison of trace element partitioning between clinopyroxene and melt in carbonate and silicate systems, and implications for mantle metasomatism. Contrib. Min. Petrol. 139, 356–371 (2000).

Ryabchikov, I. D., Orlova, G. P., Senin, V. G. & Trubkin, N. V. Partitioning of rare earth elements between phosphate-rich carbonatite melts and mantle peridotites. Mineral. Petrol. 49, 1–12 (1993).

Girnis, A. V., Bulatov, V. K., Brey, G. P., Gerdes, A. & Höfer, H. E. Trace element partitioning between mantle minerals and silico-carbonate melts at 6–12 GPa and applications to mantle metasomatism and kimberlite genesis. Lithos 160–161, 183–200 (2013).

Klemme, S., van der Laan, S. R., Foley, S. F. & Günther, D. Experimentally determined trace and minor element partitioning between clinopyroxene and carbonatite melt under upper mantle conditions. Earth Planet. Sci. Let. 133, 439–448 (1995).

Gaetani, G. A., Kent, A. J. R., Grove, T. L., Hutcheon, I. D. & Stolper, E. M. Mineral/melt partitioning of trace elements during hydrous peridotite partial melting. Contrib. Min. Petrol. 145, 391–405 (2003).

Green, T. H., Adam, J. & Sie, S. H. Trace element partitioning between silicate minerals and carbonatite at 25 kbar and application to mantle metasomatism. Min. Petrol. 46, 179–184 (1992).

Green, T. H. Experimental studies of trace-element partitioning applicable to igneous petrogenesis m Sedona 16 years later. Chem. Geol. 117, 1–36 (1994).

Sweeney, R. J., Prozesky, V. & Przybylowicz, W. Selected trace and minor element partitioning between peridotite minerals and carbonatite melts at 18–46 kbar pressure. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 59, 3671–3683 (1995).

Hammouda, T., Moine, B. N., Devidal, J. L. & Vincent, C. Trace element partitioning during partial melting of carbonated eclogites. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 174, 60–69 (2009).

Hammouda, T., Chantel, J. & Devidal, J. L. Apatite solubility in carbonatitic liquids and trace element partitioning between apatite and carbonatite at high pressure. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 74, 7220–7235 (2010).

Le Maitre, R.W. Igneous rocks: a classification and glossary of terms: recommendations of international union of geological sciences sub-commission on the systematics of igneous rocks. Cam. Un. Pr. 236 (2002).

Chebotarev, D. A., Veksler, I. V., Wohlgemuth-Ueberwasser, C., Doroshkevich, A. G. & Koch-Müller, M. Experimental study of trace element distribution between calcite, fluorite and carbonatitic melt in the system CaCO3+CaF2+Na2CO3±Ca3(PO4)2 at 100 MPa. Contrib. Min. Petrol. 174, 4 (2019).

Chakhmouradian, A. R., Reguir, E. P. & Couëslan, C. Calcite and dolomite in intrusive carbonatites II. Trace-element variations. Min. Petrol. 110, 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00710-015-0392-4 (2016).

Chakhmouradian, A. R., Reguir, E. P. & Zaitsev, A. N. Calcite and dolomite in intrusive carbonatites I. Textural variations. Min. Petrol. 110, 333–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00710-015-0390-6 (2016).

Saito, A. et al. Incorporation of incompatible strontium and barium ions into calcite (CaCO3) through amorphous calcium carbonate. Minerals 10, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/min10030270 (2020).

Matthews, W., Linnen, R. L. & Guo, Q. A filler-rod technique for controlling redox conditions in cold-seal pressure vessels. Am. Min. 88, 701–707 (2003).

Woodhead, J., Hellstrom, J., Hergt, J., Greig, A. & Maas, R. Isotopic and elemental imaging of geological materials by laser ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma mass spectrometry. J. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 31, 331–343 (2007).

Paton, C., Hellstrom, J., Paul, B., Woodhead, J. & Hergt, J. Iolite: Freeware for the visualisation and processing of mass spectrometric data. J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1ja10172b (2011).

Acknowledgements

Experiments were carried out on equipment in GFZ during visits, supported by a grant of Russian Science Foundation (19-17-00013). Microprobe and scanning electron microscopy analyses were done on state assignment of IGM SB RAS (0330-2019-0002). LA-ICP-MS analyses were done with the support of National Nature Foundation of Science of China (91962102).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A.C. developed the idea of the paper, conducted the experiments, collected and interpreted the analytical data, wrote and designed the original manuscript; C.W.-U. collected the analytical data and reviewed the original manuscript; T.H. provided support in collecting the analytical data and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chebotarev, D.A., Wohlgemuth-Ueberwasser, C. & Hou, T. Partitioning of REE between calcite and carbonatitic melt containing P, S, Si at 650–900 °C and 100 MPa. Sci Rep 12, 3320 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07330-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07330-0

This article is cited by

-

Formation of giant carbonatite rare earth deposits controlled by deep-seated magma chambers

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Age and geochemistry of carbonatites and associated silicate rocks in Sarnu-Dandali alkaline complex, Deccan Large Igneous Province: Evidence for melt immiscibility and plume-lithosphere interaction

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology (2026)

-

The effect of fluorine in the genesis of carbonatite-hosted rare earth element and niobium deposits

Science China Earth Sciences (2026)

-

Reaction-driven magmatic crystallisation at the Maoniuping carbonatite

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Trace-element partitioning between gregoryite, nyerereite, and natrocarbonatite melt: implications for natrocarbonatite evolution

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology (2023)