Abstract

CO2 reforming of CH4 (CRM) is not only beneficial to environmental protection, but also valuable for industrial application. Different CeO2 supports were prepared to investigate the matching between Ni and CeO2 over Ni/CeO2 and its effect on CRM. The physicochemical properties of Ni/CeO2-C (commercial CeO2), Ni/CeO2-H (hydrothermal method) as well as Ni/CeO2-P (precipitation method) were characterized by XRD, N2 adsorption at − 196 °C, TEM, SEM–EDS, H2-TPR, NH3-TPD and XPS. Ni0 with good dispersion and CeO2 with more oxygen vacancies were obtained on Ni/CeO2-H, proving the influence on Ni/CeO2 catalysts caused by the preparation methods of CeO2. The initial conversion of both CO2 and CH4 of Ni/CeO2-H was more than five times that of Ni/CeO2-P and Ni/CeO2-C. The better matching between Ni and CeO2 on Ni/CeO2-H was the reason for its best catalytic performance in comparison with the Ni/CeO2-C and Ni/CeO2-P samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the technology breakthrough in exploiting shale gas and combustible ice, searching clean approaches to utilize the main component CH4 efficiently has received extensive attention1,2. CO2 reforming of CH4, generally short for CRM, could convert greenhouse gas CH4 and CO2 to syngas (CO + H2). CRM is of great practical significance due to the following advantages: (1) the n(H2)/n(CO) ratio of the produced syngas is about 1, which could be directly used for Fischer–Tropsch synthesis; (2) CO2 and CH4 are greenhouse gases, and the utilization of them could really improve the ecological environment; (3) CRM requires high heat input, which means CRM could be employed for energy storage and transmission medium3,4.

Noble metal catalysts, such as Rh-5, Ru-6, Pd-7 based catalysts, exhibited good catalytic activity and strong anti-coking capacity in CRM. However, they could not be applied on an industrial scale because of their limited resources. On the contrary, the cheap and abundant non-noble metal catalysts, especially Ni-based catalysts, which give catalytic activities comparable to that of noble metal-based catalysts, have been widely studied8,9,10. Unfortunately, Ni-based catalysts generally suffer from poor stability. On one hand, at the high operating temperature of endothermic CRM (700–850 °C), Ni particles aggregate easily, which may reduce the number of active sites of the catalysts and eventually weaken the catalytic capacity11. On the other hand, filamentous carbon and active carbon are produced via CH4 cracking and CO disproportionation reactions. The accumulation and growth of these carbon species gradually cover and embed the active Ni particles and ultimately result in deteriorated catalyst stability12,13. Therefore, designing efficient Ni-based catalysts with strong anti-aggregation and anti-coking competence is critical for improving their stability in CRM.

With the aim to improve the anti-agglomeration competence of Ni-based catalysts, several approaches have been adopted, including (1) adding a structure promoter to stabilize Ni particles and (2) enhancing the Ni-support interaction to prevent the movement of Ni particles. For example, the Ni particles on Ni/SBA-15 catalyst modified by 1 wt% Sn (served as the structure promoter) were smaller and not easy to aggregate than those on unmodified catalyst14; the strong interaction between Ni and Al2O3 over Ni/Al2O3 catalyst, evidenced by the formation of NiAl2O4, prevents the aggregation of Ni particles greatly15,16. As for improving the anti-coking competence of Ni-based catalysts, the following routes are proved promising. (1) Adopting Ni-based catalysts with small Ni particles, since it is well accepted that smaller Ni particles exhibit stronger anti-coking competence17,18; (2) Adjusting the basic properties of Ni-based catalysts to facilitate CO2 adsorption and accelerate reverse CO disproportionation reaction, which could help to eliminate the deposited coke by the adsorbed CO219,20. (3) Utilizing a material with strong oxygen storage capacity as support, which could serve as an oxygen reservoir for the elimination of deposited coke via oxidation reaction21,22.

Based on the research progress made by predecessors, it could be speculated that Ni/CeO2 catalyst with a large specific surface might be good for CRM, owing to (1) the Ni particles on a catalyst with a large specific surface area are generally well dispersed, and the interaction between Ni particles and CeO2 might be strong; (2) CeO2 is of basic properties23, which could facilitate CO2 adsorption and help to eliminate the deposited coke; (3) the oxidation–reduction property of CeO2 renders it as a strong oxygen reservoir24, which is ready to react with the deposited coke. Several groups have synthesized Ni/CeO2 catalysts and investigated their performance in CRM. However, controversial conclusions have been obtained. For instance, Shao et al. synthesized Ni/CeO2 via microemulsion method and reported that the as-prepared catalyst had smaller Ni particles (6–13 nm, with an average of 11 nm) and exhibited high activity in CRM25. Yahi et al. compared the catalytic performance of Ni/CeO2 prepared by auto-combustion method, sol–gel method and microemulsion method. It is discovered that, Ni/CeO2 prepared by microemulsion method (the average size of Ni particles were 11 nm) did not show any catalytic activity26. Holgado et al. got Ni/CeO2 (the size of Ni particles was in the range of 12–18 nm) by combustion method, which recorded a high activity but poor stability27. Rosen et al. synthesized Ni/CeO2 solid solution via exsolution method, which showed active and stable performance in CRM at 800 °C (The size of Ni particles was not clearly stated)28. Rodriguez et al. utilized theoretical calculation to investigate Ni/CeO2 catalyst and reported that it was a highly active catalyst for CRM even at a temperature as low as 700 K, and the strong interaction between Ni and CeO2 plays crucial roles in cleaving the C–H bond in CH429. Ganduglia-Pirovano et al. considered that Ce3+ sites and the interaction between Ni and CeO2 worked in concert to cleave the C–H bond30. Zhu et al. treated Ni and CeO2 by plasma to get clean Ni–CeO2 interface, which was regarded to be responsible for its high activity in CRM31. Therefore, the preparation method of CeO2 has a great influence on the activity of Ni/CeO2 in CRM. Many studies focus on the small size of Ni, however, sometimes, Ni/CeO2 catalysts with small size of Ni still exhibit unsatisfactory catalytic performance. The controversial conclusions might be caused by the poor matching between Ni and CeO2 supports, and it is difficult to get a generalized guidance for the rational design of efficient catalysts.

For studying the impact of the synthesis procedures of CeO2 supports on the catalytic performance of the binary oxides, the low Ni content and the introduction method of Ni were control the same, and CeO2 prepared by three different methods were used as the supports of Ni/CeO2 catalysts. The properties of three kinds of CeO2 and their supported Ni-based catalysts were characterized, and the performance of Ni/CeO2 catalysts in CRM were evaluated.

Experimental section

Catalyst preparation

Chemicals in this study were of analytical grade and used as received. CeO2-H was used to denote CeO2 prepared by hydrothermal method. It was prepared via the following procedure: 11.2 g CeCl3·7H2O and 9.4 g cetyltriethylammnonium bromide (CTAB) were firstly dissolved in 550 mL deionized water, to which 25 mL 25 wt% NH3 solution was then added drop-wisely. The slurry was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then treated at 90 °C for 30 h with reflux. After cooling down to room temperature, it was washed by deionized water and acetone to neutral. Finally, it was dried at 80 °C for 24 h and calcined in air at 700 °C (at a heating ramp of 2 °C min−1) for 5 h to obtain CeO2-H. CeO2-P was used to denote CeO2 prepared by precipitation method. It was prepared via the following procedure: 250 mL 0.2 wt% NH3 solution and 250 mL 16.0 g L−1 CeCl3 solution were added drop-wisely to another 250 mL 0.2 wt% NH3 solution under vigorous stir. The slurry was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then aged for 12 h. After centrifugation, it was washed by deionized water and acetone to neutral. Finally, it was dried at 80 °C for 24 h and calcined in air at 700 °C (at a heating ramp of 2 °C min−1) for 5 h to obtain CeO2-P.

CeO2-H, CeO2-P, together with commercial CeO2 (denoted as CeO2-C) were used as supports of Ni-based catalysts. Ni/CeO2 catalysts were prepared by loading a certain amount of Ni(NO3)2 onto the CeO2 supports using the wetness impregnation method. After impregnating for 10 h, the samples were evaporated, dried at 80 °C and calcined at 700 °C for 5 h. The as-prepared catalysts were denoted as Ni/CeO2-H, Ni/CeO2-P and Ni/CeO2-C, respectively.

Catalyst characterization

The crystalline structures of CeO2 and Ni/CeO2 catalysts were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) method on an X-Pert diffractometer equipped with graphite monochromatized Cu-Kα radiation. The specific surface areas were determined using a surface area analyzer (BEL Sorp-II mini, BEL Japan Co., Japan) with the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. Shape of the samples were observed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM-16-TS-008) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). H2-temperature programmed reduction (TPR), CO2-temperature programmed desorption (CO2-TPD) and NH3-temperature programmed desorption (NH3-TPD) profiles were carried out over Quantachrome instrument, with the temperature raising from room temperature to 900 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out on Thermo Fisher equipped with Al Kα radiation. Binding energies were calibrated by carbon (C 1s, 284.6 eV). The amount of coke deposited on the spent catalysts was characterized by Thermogravimetry (TG). The composition of the samples was determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) on a 730 Series ICP-OES by Agilent Technologies.

Catalyst evaluation

CRM reaction was conducted in a fixed-bed reactor under atmospheric pressure. A portion of 0.20 g catalyst was packed uniformly in the temperature-constant zone of a quartz tube. Before reaction, the catalysts were reduced by 20% H2/Ar at 700 °C for 1 h. Then 20.0 mL min−1 (STP) CH4 and 20.0 mL min−1 (STP) CO2 were introduced into the reactor as reactants, with WHSV of 4.3 h−1 for CH4 and 11.8 h−1 for CO2. After removing the byproduct water via an ice trap, the effluent gas was analyzed by a gas chromatography equipped with a TDX-01 column to determine the relative amounts of CH4, CO, CO2 and H2, and the flow rate of the effluent gas was measured with a flow meter.

Results and discussion

Crystalline structure of CeO2 and Ni/CeO2 catalysts

The crystalline structures of CeO2 and Ni/CeO2 catalysts were characterized by XRD, and the results were displayed in Fig. 1. The intense and sharp diffraction peaks at 28.6, 33.1, 47.5, 56.3, 59.1, 69.4, 77.0 and 79.1 in Fig. 1a were assigned to fluorite-structured CeO2 (JSPDS 34-394)32,33, indicating CeO2-H and CeO2-P were successfully synthesized. The crystalline structure of CeO2 changed little after the loading of Ni (Fig. 1b), and no obvious diffraction peaks assigned to Ni species were observed. ICP results showed that the actual Ni loading for Ni/CeO2-H (0.80 wt%), Ni/CeO2-C (0.84 wt%) and Ni/CeO2-P (0.81 wt%) was low, which may below the detection limit of XRD analysis.

Textural properties of CeO2 and Ni/CeO2 catalysts

The textual properties of CeO2 and Ni/CeO2 catalysts were obtained by N2 adsorption–desorption technique, and N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of different Ni/CeO2 based catalysts were shown in Fig. 2. The H4 hysteresis loops of Ni/CeO2-H and Ni/CeO2-P suggested the presence of mesoporous structures and the volume of mesoporous (Vmes) (Table 1) verified it. The specific surface area (SBET) was also given in Table 1, and as can be seen that after the introduction of 0.8 wt% Ni on CeO2 supports, SBET of all the three catalysts decreased slightly and Vmes remained the same.

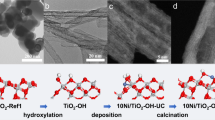

Morphologies of Ni/CeO2 catalysts

The morphologies of Ni/CeO2 catalysts were observed via TEM and SEM. Over the TEM images of three Ni/CeO2 catalysts (Fig. 3), nanoparticles assigned to CeO2 could be clearly observed. Obviously, CeO2 over Ni/CeO2-P was somewhat large, in the range of 10–40 nm (Fig. 3a); CeO2 over Ni/CeO2-H was relatively uniform and small, around 10 nm (Fig. 3b); Meanwhile, the size of CeO2 over Ni/CeO2-C was the largest, 60–100 nm (Fig. 3c). Notably, no Ni species were detected in the TEM images, inferring that Ni was well dispersed on three catalysts, and the crystallite size of CeO2 in the three catalysts barely changed before and after the introduction of Ni (Table 1), which may be related to the low Ni loading.

Furthermore, the chemical analysis of the mixed oxides by SEM and the corresponding EDS were conducted to investigate the elemental distribution and the homogeneity of the three Ni/CeO2 catalysts. As was shown in Fig. 4, Ni, O and Ce elements were uniformly distributed on Ni/CeO2-H catalyst. The same results could also be obtained for Ni/CeO2-P (Fig. S1) and Ni/CeO2-C (Fig. S2), which further proved that Ni has a good dispersion state on the three Ni/CeO2 catalysts.

Acidic-basic properties of Ni/CeO2 catalysts

Acidic properties of different Ni/CeO2 catalysts were characterized by NH3-TPD, and the results were illustrated in Fig. 5. As was shown in Fig. 5a, there was only one obvious desorption peak (150 °C) over Ni/CeO2-C corresponding to the weak acid sites. More weak (187 °C) and strong (550 °C) acid sites, especially for weak, were observed on Ni/CeO2-P. It was noting that on Ni/CeO2-H, there was a big and wide peak ranging from 130 to 900 °C, corresponds to the maximum amount of weak, medium and strong acid sites. The acid properties of different CeO2 supports were also tested and shown in Fig. 5b. There were more weak acids on CeO2-P and more medium as well as strong acid sites on CeO2-H than CeO2-C. Such differences came from different preparation methods of CeO2.

CO2-TPD experiment was performed to study the basic properties of Ni/CeO2-P, Ni/CeO2-H and Ni/CeO2-C, and the results were shown in Fig. 6 and Table 2. It could be found that two main peaks of CO2 desorption were observed at 168 °C and 620 °C over Ni/CeO2-C and the overall desorption amount was the least, proving the weak and less basic sites of Ni/CeO2-C. There were two peaks centered at 183 °C and 517 °C and an incredible amount of CO2 desorption was detected on Ni/CeO2-P, indicating a large number of weak basic sites on Ni/CeO2-P. For Ni/CeO2-H, there were four peaks corresponding to weak (173 °C), medium weak (402 °C), medium strong (622 °C) and strong (863 °C) basic sites, showing the diverse basic properties of the sample prepared by hydrothermal method. CO2 adsorption values of prepared catalysts in Table 2 demonstrated it. It should be noted that CO2 was one of the reactants, and the highest desorption temperature (863 °C) seems to mean that the binding effect between Ni/CeO2-H catalyst and CO2 was strong, which may be conducive to the CO2 reaction.

The state of Ni and CeO2 over Ni/CeO2 catalysts

H2-TPR experiment was performed to study the state of Ni and CeO2 during the reducing atmosphere, and the results were shown in Fig. 7. It could be found in Fig. 7a that there were three major peaks at the temperature of 100–600 °C, 366 °C for Ni/CeO2-C, 350 °C for Ni/CeO2-P and 319 °C for Ni/CeO2-H, respectively. It is generally accepted that the smaller the NiO particle size, the lower the hydrogen consumption temperature. Therefore, it could be inferred that the particle size of bulk NiO particles decreased in the order of Ni/CeO2-C, Ni/CeO2-P and Ni/CeO2-H. There were also two relatively small peaks on Ni/CeO2-P (239 °C) and Ni/CeO2-C (272 °C), which were attributed to surface NiO. The H2-TPR profiles of three CeO2 were depicted in Fig. 7b, and as was shown that two obvious peaks could be observed on all samples: low-temperature peak for surface shell reduction (Ce4+ to Ce3+) and high-temperature peak for bulk reduction. Comparing the two figures in Fig. 7, the shoulder peak at 476 °C on Ni/CeO2-H should be attributed to surface CeO2.

Surface structures of Ni/CeO2 catalysts

XPS was used to clarify the surface chemical environment and the valence state of elements on the reduced Ni/CeO2 catalysts, and the results were shown in Fig. 8. As shown in Fig. 8a, there were three peaks located at about 853.2, 855.1, and 860.8 eV, attributed to Ni0, Ni2+, and the satellite peak of Ni 2p3/2 on reduced Ni/CeO2-H34. In contrast, Ni0 was almost absent on Ni/CeO2-C and Ni/CeO2-P. Figure 8b showed the XPS spectra of O 1s region for different Ni/CeO2 catalysts. O 1s peaks at 528.6–529.1 eV were assigned to lattice oxygen, while peaks at 530.4–531.2 eV were assigned to oxygen vacancies. In conclusion, after reduction treatment, the most Ni0 and oxygen vacancies were obtained over Ni/CeO2-H among the three catalysts.

Catalytic performance of Ni/CeO2 catalysts in CRM

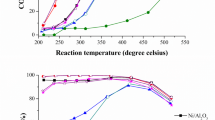

The catalytic performance of Ni/CeO2 catalysts in CRM were evaluated in a fixed bed reactor and the results were shown in Fig. 9. It was clear that Ni/CeO2-H exhibited high catalytic activity (The initial CO2 and CH4 conversions were 75% and 71%, respectively). On the contrary, the catalytic performance of Ni/CeO2-P and Ni/CeO2-C was poor (the initial CO2 and CH4 conversions were within 20%). The conversion of more than five times proved the superiority of Ni/CeO2-H. Due to the reverse water gas shift reaction, CO2 conversion was higher than CH4 conversion over all the three Ni/CeO2 catalysts. After 480 min time on stream, CO2 conversion dropped from 75 to 48% and CH4 conversion dropped from 71 to 35%. The unsatisfied stability of Ni–CeO2-H might be caused by coke. For comparison, CRM reaction of CeO2-H, CeO2-P and CeO2-C was also evaluated. The activity of three prepared bare CeO2 supports in this work was nearly inert (both CH4 and CO2 conversion were less than 3%), which indicated that Ni played a crucial role in CRM reaction, and the preparation method of CeO2 has a great influence on the matching between Ni and CeO2.

Crystalline structure of spent Ni/CeO2 catalysts

The crystalline structure of spent Ni/CeO2 catalysts was further characterized by XRD, and the results were displayed in Fig. 10. The nearly unchanged diffraction peaks between fresh and spent Ni/CeO2 catalysts revealed that the crystalline structure of CeO2 did not change during the reaction atmosphere. No obvious diffraction peaks assigned to Ni species were observed.

TG of spent Ni/CeO2 catalysts

The coking behavior of spent catalysts of Ni/CeO2-C, Ni/CeO2-P and Ni/CeO2-H was tested by TG, and the results were shown in Fig. 11. As can be seen, the similar two stages of weight change could be found over Ni/CeO2-C and Ni/CeO2-P, and the 0.3% increase in mass should be attributed to the oxidation process of Ni and the oxygen species adsorbed by oxygen vacancies of CeO2 supports in the first stage (100–425 °C). Since the catalytic activity was weak, there was almost no weight loss for Ni/CeO2-C and Ni/CeO2-P in the second stage (425–850 °C). As for Ni/CeO2-H, almost no weight change was observed during the first parts (100–382 °C), which may possibly because Ni and oxygen vacancies with catalytic activity were occupied by coke, and the 0.7% weight loss in the second stage (380–850 °C) should be corresponded to the amount of coke. The BET surface area of the spent Ni/CeO2-H (17.9 m2 g−1) proved the covering effect of coke on the catalyst.

Matching of Ni and CeO2 on Ni/CeO2 catalysts in CRM

The activation of Ni to CH4 and CeO2 to CO2 are very important for CRM reaction. On one hand, small Ni particles have a strong ability to activate the C-H bond of alkanes, while the aggregated Ni could easily induce CH4 cracking to produce coke12. Therefore, it is very important to prepare small Ni particles with high dispersion. On the other hand, basic CeO2 with more oxygen vacancies is beneficial to the chemisorption and dissociation of CO235. The results of H2-TPR (Fig. 7) and XPS (Fig. 8) manifested that small Ni and CeO2 with more oxygen vacancies were obtained on Ni/CeO2-H through hydrothermal method, and the matching of Ni and CeO2 has been effectively demonstrated by the catalytic performance (Fig. 9). What was more, CO2 dissociation and thereafter oxidation of carbon deposit can take place over low acidic catalyst system. So, Low acid catalyst system is expected to improve the stability of catalysts to a certain extent.

Conclusions

Three Ni/CeO2 catalysts were prepared by different method, and the matching between Ni and different CeO2 supports as well as their effects on CRM reaction have been well studied. The conversions of CO2 and CH4 of Ni/CeO2-P were slightly better than that of Ni/CeO2-C, and the catalytic activity of Ni/CeO2-H was more than 5 times that of Ni/CeO2-P or Ni/CeO2-C. According to the results of related characterization and evaluation, it can be concluded that the better matching of Ni and CeO2, including Ni0 with good dispersion and CeO2 with more oxygen vacancies, was the fundamental reason for improving the reaction activity of CRM. It is a remarkable fact that coke has a great influence on the stability of catalysts, and necessary experiments are still needed. This work investigated and demonstrated the advantages and differences of hydrothermal preparation of CeO2 supports and throw new light on the design of highly efficient Ni/CeO2 catalysts for CRM.

References

Löfberg, A., Kane, T., Guerrero-Caballero, J. & Jalowiecki-Duhamel, L. Chemical looping dry reforming of methane: Toward shale-gas and biogas valorization. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intens. 122, 523–529 (2017).

Martinez-Gomez, J., Nápoles-Rivera, F., Ponce-Ortega, J. M. & El-Halwagi, M. M. Optimization of the production of syngas from shale gas with economic and safety considerations. Appl. Therm. Eng. 110, 678–685 (2017).

Fan, M.-S., Abdullah, A. Z. & Bhatia, S. Catalytic technology for carbon dioxide reforming of methane to Synthesis Gas. ChemCatChem 1, 192–208 (2009).

Pakhare, D. & Spivey, J. A review of dry (CO2) reforming of methane over noble metal catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 7813–7837 (2014).

Maestri, M., Vlachos, D. G., Beretta, A., Groppi, G. & Tronconi, E. Steam and dry reforming of methane on Rh: Microkinetic analysis and hierarchy of kinetic models. J. Catal. 259, 211–222 (2008).

Ferreira-Aparicio, P., Rodriguez-Ramos, I., Anderson, J. A. & Guerrero-Ruiz, A. Mechanistic aspects of the dry reforming of methane over ruthenium catalysts. Appl. Catal. A 202, 183–196 (2000).

Barama, S., Dupeyrat-Batiot, C., Capron, M., Bordes-Richard, E. & Bakhti-Mohammedi, O. Catalytic properties of Rh, Ni, Pd and Ce supported on Al-pillared montmorillonites in dry reforming of methane. Catal. Today 141, 385–392 (2009).

Abdullah, B., Ghani, N. A. A. & Vo, D.-V.N. Recent advances in dry reforming of methane over Ni-based catalysts. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 170–185 (2017).

Wang, Y., Yao, L., Wang, S., Mao, D. & Hu, C. Low-temperature catalytic CO2 dry reforming of methane on Ni-based catalysts: A review. Fuel Process. Technol. 169, 199–206 (2018).

Zhang, G., Liu, J., Xu, Y. & Sun, Y. A review of CH4-CO2 reforming to synthesis gas over Ni-based catalysts in recent years (2010–2017). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43, 15030–15054 (2018).

Xie, T., Shi, L., Zhang, J. & Zhang, D. Immobilizing Ni nanoparticles to mesoporous silica with size and location control via a polyol-assisted route for coking- and sintering-resistant dry reforming of methane. Chem. Commun. 50, 7250–7253 (2014).

Therdthianwong, S., Siangchin, C. & Therdthianwong, A. Improvement of coke resistance of Ni/Al2O3 catalyst in CH4/CO2 reforming by ZrO2 addition. Fuel Process. Technol. 89, 160–168 (2008).

Das, S. et al. Silica-Ceria sandwiched Ni core-shell catalyst for low temperature dry reforming of biogas: Coke resistance and mechanistic insights. Appl. Catal. B 230, 220–236 (2018).

Taherian, Z., Yousefpour, M., Tajally, M. & Khoshandam, B. Catalytic performance of Samaria-promoted Ni and Co/SBA-15 catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 24811–24822 (2017).

Newnham, J., Mantri, K., Amin, M. H., Tardio, J. & Bhargava, S. K. Highly stable and active Ni-mesoporous alumina catalysts for dry reforming of methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37, 1454–1464 (2012).

Zhou, L., Li, L., Wei, N., Li, J. & Basset, J.-M. Effect of NiAl2O4 formation on Ni/Al2O3 stability during dry reforming of methane. ChemCatChem 7, 2508–2516 (2015).

Jing, J.-Y., Wei, Z.-H., Zhang, Y.-B., Bai, H.-C. & Li, W.-Y. Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over MgO-promoted Ni/SiO2 catalysts with tunable Ni particle size. Catal. Today 356, 589–596 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. CO2 reforming with methane over small-sized Ni@SiO2 catalysts with unique features of sintering-free and low carbon. Appl. Catal. B 235, 26–35 (2018).

García, V., Fernández, J. J., Ruíz, W., Mondragón, F. & Moreno, A. Effect of MgO addition on the basicity of Ni/ZrO2 and on its catalytic activity in carbon dioxide reforming of methane. Catal. Commun. 11, 240–246 (2009).

Osaki, T. Role of alkali or alkaline earth metals as additives to Co/Al2O3 in suppressing carbon formation during CO2 reforming of CH4. Kinet. Catal. 60, 818–822 (2019).

Özcan, M. D., Özcan, O., Kibar, M. E. & Akin, A. N. Preparation of Ni-CeO2/MgAl hydrotalcite-like catalyst for biogas oxidative steam reforming. J. Fac. Eng. Arch. Gazi Univ. 34, 1128–1142 (2019).

Wang, S. & Lu, G. Q. Role of CeO2 in Ni/CeO2-Al2O3 catalysts for carbon dioxide reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. B 19, 267–277 (1998).

Paunović, V., Zichittella, G., Mitchell, S., Hauert, R. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Selective methane oxybromination over nanostructured ceria catalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 291–303 (2018).

Machida, M., Kawada, T., Fujii, H. & Hinokuma, S. The role of CeO2 as a gateway for oxygen storage over CeO2-Grafted Fe2O3 composite materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 24932–24941 (2015).

Liu, C. et al. Synthesis of Ni-CeO2 nanocatalyst by the microemulsion-gas method in a rotor-stator reactor check. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intens. 130, 93–100 (2018).

Yahi, N., Menad, S. & Rodríguez-Ramos, I. Dry reforming of methane over Ni/CeO2 catalysts prepared by three different methods. Green Process. Synth. 4, 479–486 (2015).

Gonzalez-Delacruz, V. M., Ternero, F., Pereñíguez, R., Caballero, A. & Holgado, J. P. Study of nanostructured Ni/CeO2 catalysts prepared by combustion synthesis in dry reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. A 384, 1–9 (2010).

Padi, S. P. et al. Coke-free methane dry reforming over nano-sized NiO-CeO2 solid solution after exsolution. Catal. Commun. 138, 105951 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Dry reforming of methane on a highly-active Ni-CeO2 catalyst: Effects of metal-support interactions on C–H bond breaking. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 7455–7459 (2016).

Lustemberg, P. G. et al. Room-temperature activation of methane and dry re-forming with CO2 on Ni-CeO2 (111) surfaces: Effect of Ce3+ sites and metal-support interactions on C–H bond sleavage. ACS Catal. 6, 8184–8191 (2016).

Odedairo, T., Chen, J. & Zhu, Z. Metal-support interface of a novel Ni-CeO2 catalyst for dry reforming of methane. Catal. Commun. 31, 25–31 (2013).

Wang, X. et al. In situ studies of the active sites for the water gas shift reaction over Cu-CeO2 catalysts: Complex interaction between metallic copper and oxygen vacancies of ceria. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 428–434 (2006).

Ho, C., Yu, J. C., Kwong, T., Mak, A. C. & Lai, S. Morphology-controllable synthesis of mesoporous CeO2 nano- and microstructures. Chem. Mater. 17, 4514–4522 (2005).

Qin, Z., Chen, L., Chen, J., Su, T. & Ji, H. Ni/CeO2 prepared by improved polyol method for CRM with highly dispersed Ni. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 11, 1245–1264 (2021).

Cárdenas-Arenas, A., Bailón-García, E., Lozano-Castelló, D., Costa, P. D. & Bueno-López, A. Stable NiO–CeO2 nanoparticles with improved carbon resistance for methane dry reforming. J. Rare Earths 40, 57–62 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work received financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21902116).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.N.: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft. X.D.: Data curation, Writing—review & editing. X.G.: Writing—review & editing. J.W.: Formal analysis. H.L.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition. Q.Z.: Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ni, Z., Djitcheu, X., Gao, X. et al. Effect of preparation methods of CeO2 on the properties and performance of Ni/CeO2 in CO2 reforming of CH4. Sci Rep 12, 5344 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09291-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09291-w

This article is cited by

-

Basicity as a descriptor for catalyst performance: a promoter study for syngas production via autothermal reforming of methane with CO₂

Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy (2026)