Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis has been suggested for patients who underwent total join arthroplasty (TJA). However, the morbidity of surgical site complications (SSC) and periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) has not been well evaluated. We aimed to evaluate the impact of VTE prophylaxis on the risk of early postoperative SSC and PJI in a Taiwanese population. We retrospectively reviewed 7511 patients who underwent primary TJA performed by a single surgeon from 2010 through 2019. We evaluated the rates of SSC and PJI in the early postoperative period (30-day, 90-day) as well as 1-year reoperations. Multivariate regression analysis was used to identify possible risk factors associated with SSC and PJI, including age, sex, WHO classification of weight status, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), rheumatoid arthritis(RA), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), history of VTE, presence of varicose veins, total knee or hip arthroplasty procedure, unilateral or bilateral procedure, or receiving VTE prophylaxis or blood transfusion. The overall 90-day rates of SSC and PJI were 1.1% (N = 80) and 0.2% (N = 16). VTE prophylaxis was a risk factor for 90-day readmission for SSC (aOR: 1.753, 95% CI 1.081–2.842), 90-day readmission for PJI (aOR: 3.267, 95% CI 1.026–10.402) and all 90-day PJI events (aOR: 3.222, 95% CI 1.200–8.656). Other risk factors included DM, underweight, obesity, bilateral TJA procedure, younger age, male sex and RA. Pharmacological thromboprophylaxis appears to be a modifiable risk factor for SSC and PJI in the early postoperative period. The increased infection risk should be carefully weighed in patients who received pharmacological VTE prophylaxis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative venous thromboembolism (VTE) is one of the most serious complications following total joint arthroplasty (TJA), including total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA)1. The symptomatic VTE rate in the early postoperative period might be as high as 4.3%1. Therefore, pharmacological VTE prophylaxis with warfarin, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), factor Xa inhibitors (fondaparinux, apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban), or aspirin has been suggested in several guidelines1,2. Because of the lower rates of VTE in Asian population3,4,5, pharmacological VTE prophylaxis would be administered for Asian patients undergoing TJA procedures based on VTE and bleeding risk6,7. For patients who had history of VTE, varicose veins, congestive heart failure, thromboembolic stroke, family history of VTE, underwent a simultaneous bilateral TJA procedure or a prolonged procedure (> 2 h), the VTE risk was considered elevated6. Factors associated with increased bleeding risk included advanced age, active cancer with or without metastasis, liver or renal failure, thrombocytopenia, hemophilia and other bleeding disorders6. For patients without elevated VTE risk, mechanical prophylaxis alone without the need for pharmacological prophylaxis was recommended from the Asia–Pacific VTE Consensus Group6,7. The risk of VTE and risk of bleeding were the two main factors used to justify the prophylaxis strategy6. However, other adverse events associated with pharmacological VTE prophylaxis should also be considered, such as surgical site complications (SSC) and periprosthetic joint infection (PJI), which have not been well evaluated. Pharmacological VTE prophylaxis has been shown to increase the risk of wound drainage. However, the risk of subsequent wound infection was not uniformly observed across all TJA procedures7,8,9.

There were only a few comparative studies that have evaluated the risk of SSC and PJI associated with VTE prophylaxis10,11,12. More evidence is required to evaluate the overall incidence and risk of infection associate with VTE prophylaxis. Therefore, we conducted this single-surgeon case series from a tertiary referral hospital over a 10-year study period in a Taiwanese population. The aim of this study was to evaluate the risk factors for SSC and PJI events in the early postoperative period. We hypothesized that VTE prophylaxis was a risk factor for early SSC and PJI events and thus these events should be given careful consideration when making treatment decisions.

Materials and methods

Data collection

We conducted this retrospective, single-surgeon case series in Taipei Veterans General Hospital (TVGH), a tertiary referral hospital in Taipei, Taiwan. The Institutional Review Board of TVGH approved this study. Because of the retrospective design of this observational study, the TVGH Institutional Review Board has approved our request to waive the documentation of the inform consent. We obtained medical records and images from TVGH Orthopaedic database between January 2010 and December 2019. Patients who had undergone unilateral or simultaneous bilateral primary TJA, including TKA or THA during this study period were included. We screened for patients that were eligible for analysis using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance procedure codes: “PCS-64169B, TKA” and “PCS-64162B, THA”. Indications for primary TKA procedures included primary or secondary knee osteoarthritis (ICD-10-CM code: M17), spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SONK, ICD-10-CM code: M90.55, M90.56), rheumatoid arthritis of knee joint (RA, ICD-10-CM code: M05.76, M05.86, M06.86, M06.9). Indications for primary THA procedures for primary or secondary hip osteoarthritis (ICD-10-CM code M16), osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH, ICD-10-CM code: M87.05, M87.15, M87.25, M87.35, M87.85) and RA of hip joint (ICD-10-CM code: M05.75, M05.85, M06.85, M08.45, M08.85, M08.95). We excluded patients that (1) underwent primary TJA following resection of musculoskeletal tumors; (2) underwent primary TJA for acute acetabular or proximal femur fractures; (3) were allergic to LMWH or aspirin; (4) had bleeding disorders (e.g. hemophilia); (5) had Child–Pugh class B or C cirrhosis; (6) had active or a history of knee or hip infection.

Three authors (WLC, FYP and SWT) reviewed all medical records. We recorded age, sex, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), history of smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), presence of varicose vein, type of procedure (TKA or THA), unilateral or bilateral procedure, receipt of VTE prophylaxis or transfusion, length of stay (LOS) and in-hospital mortality.

Protocol for thromboprophylaxis of venous thromboembolism

During January 2010 to December 2017, the indications for VTE prophylaxis included BMI ≥ 30 (kg/m2), presence of varicose veins, or a history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). However, in December 2017, a patient underwent simultaneous bilateral TKA who did not meet the criteria of VTE prophylaxis mentioned above but developed PE during the perioperative period. Therefore, simultaneous bilateral TKA or THA was added as an indication for VTE prophylaxis from January 2018.

The thromboprophylaxis protocol consisted of an injection of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH, Enoxaparin, Clexane, 2000 IU, 0.2 cc) at the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) immediately after surgery and every day until post-operative day (POD) 3. On POD 4, LMWH was switched to low-dose aspirin (Bokey®, 100 mg) for 2 weeks. If the patient was diagnosed with a DVT based on clinical symptoms and positive ultrasonography, low-dose aspirin would then be given for a total of 5 weeks.

Surgical technique and post-operative care

All procedures were performed by a single fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeon (WMC) under spinal or general anesthesia. All the TKA procedures were performed through a minimally invasive mid-vastus approach13. The TKA components were fixed with cement. A tourniquet and a close-suction drain were used in every TKA procedure. The types of the TKA prostheses included Nexgen (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA), NRG (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA) and Triathlon (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA). All the THA procedures were performed through a minimally invasive trans-gluteal approach14. All the THA components were cementless. A close-suction drain was used in every THA procedure. The only type of THA prosthesis was the Trident cup (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA) and SecurFit femoral stem (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA). For patients who received a TKA procedure, a single-dose, intra-articular tranexamic acid was given after wound closure. For patients who underwent a THA procedure, a single-dose, intravenous tranexamic acid was given immediately before incision.

Intravenous prophylactic antibiotics were administered for 24 h after the TJA procedure unless there was evidence of any infection. All patients started rehabilitation and ambulation on POD 1. We routinely checked hemoglobin level on POD 1. If the hemoglobin level was < 9.0 g/dL or between 9.0–10.0 g/dL with symptoms of anemia, including malaise, dizziness, hypotension or tachycardia, we would transfuse the patients with 1–2 units of packed red blood cells.

Outcome domains

We aimed to evaluate the incidence of SSC and PJI at different time points. SSC was defined as hematoma, seroma, delayed wound healing, or superficial wound infection that required systemic antibiotics or a surgical debridement procedure. PJI is a more severe type of infection involving the bone and prosthesis surface that required extensive debridement or removal of the prosthesis. The outcome domains included 30-day and 90-day readmission for SSC or PJI, 90-day SSC or PJI events, and 1-year reoperation for SSC or PJI. The 30-day and 90-day readmission included a hospital readmission or a return visit to the emergency department. The all 90-day SSC or PJI events included readmissions and events that were identified and treated at the outpatient follow-up visits.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses for this study were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were performed for all available data. The Chi-square test was used for comparing discrete variable. When one or more of the cells in the contingency table had an expected frequency of less than 5, we performed the Fisher’s exact test. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine risk factors for SSC and PJI, including age, sex, WHO classification of weight status15, smoking, DM, RA, CCI, history of VTE, presence of varicose veins, TKA or THA procedure, unilateral or bilateral procedure, or receiving VTE prophylaxis or blood transfusion. The backward variable selection method was employed to choose the optimal model, with the significance test for a risk factor entering and remaining at the significance level of 0.05. The results were expressed as an odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethical committee of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. Because of the retrospective design of this observational study, the TVGH Institutional Review Board has approved our request to waive the documentation of the inform consent. The study was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Outcome

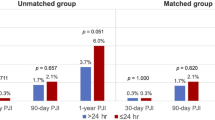

A total of 7511 patients who had undergone a TJA procedure were included for analysis. The rates of 90-day symptomatic VTE events in patients who received pharmacological thromboprophylaxis and those did not were 0.20% (N = 4) and 0.52% (N = 29), respectively. The patient demographics have been shown in Table 1. The overall rates of 30-day readmission for SSC and PJI were 0.8% (N = 58) and 0.1% (N = 9), respectively. The overall rates of 90-day readmission for SSC and PJI were 0.9% (N = 71) and 0.2% (N = 12), respectively. The overall incidence of SSC and PJI within 90 days after the TJA procedure were 1.1% (N = 80) and 0.2% (N = 16), respectively. The overall 1-year reoperation rates for SSC and PJI were 0.1% (N = 11) and 0.4% (N = 29), respectively. The rates of SSC and PJI stratified by the administration of VTE prophylaxis are shown in Table 2. The rates of 30-day (1.1% vs. 0.6%, p = 0.041), 90-day readmission for SSC (1.4% vs. 0.8%, p = 0.011) and the overall incidence of SSC (1.5% vs. 0.9%, p = 0.039) and PJI (0.4% vs. 0.1%, p = 0.037) within 90 days after the TJA procedure were higher in patients who received pharmacological thromboprophylaxis, compared with those who did not (Table 2).

Risk factors for SSC

DM was a risk factor for 30-day (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 2.135; 95% CI 1.246–3.658) and 90-day (aOR: 1.673; 95% CI 1.010–2.773) readmission for SSC. The administration of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (aOR: 1.753; 95% CI 1.081–2.842) was associated with increased risk of 90-day readmission for SSC. Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) patients had an increased risk of SSC events within 90 days after the TJA procedure (aOR: 1.803; 95% CI 1.135–2.863). None of the factors recorded in this study were associated with an increased risk of 1-year reoperation for SSC (Table 3). The results of the univariate and multivariate analysis of all the registered variables were shown in Tables S1–8.

Risk factor for PJI

Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, aOR: 11.692; 95% CI 1.417–96.482) and simultaneous bilateral TJA procedure (aOR: 4.882; 95% CI 1.295–18.400) were associated with an increased risk of 30-day readmission for PJI. The administration of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis was a risk factor for 90-day readmission for PJI (aOR: 3.267; 95% CI 1.026–10.402) as well as having a PJI event within postoperative 90 days (aOR: 3.222; 95% CI 1.200–8.656). Male patients were at an increased risk of 90-day PJI events (aOR: 3.568; 95% CI 1.328–9.583) and 1-year reoperation for PJI (aOR: 2.738; 95% CI 1.308–5.731). Younger age was a risk factor for 90-day readmission for PJI (aOR: 0.959; 95% CI 0.920–0.999), while RA (aOR: 5.048; 95% CI 1.501–16.974) was another risk factor for 1-year reoperation for PJI (Table 3). The results of the univariate and multivariate analysis of all the registered variables were shown in Tables S1–8.

Discussion

The most important finding of this study was that VTE prophylaxis with a combination of LMWH and aspirin was a major risk factor for SSC and PJI in the early postoperative period. Other factors included DM, obesity, underweight, simultaneous bilateral procedures, younger age, male sex, and RA.

Risk of VTE and bleeding are two major factors to consider when choosing a thromboprophylaxis strategy6. However, risk of infection associated with pharmacological VTE prophylaxis was another important issue that has not been well evaluated. Pharmacological VTE prophylaxis might lead to (1) postoperative hematoma, which acts as a nidus for bacteria to settle, and (2) prolonged wound drainage, which increases wound tension, bypasses the natural barrier of the skin, increases risk of wound dehiscence and provides a retrograde pathway for pathogens8,11,16, but whether the pharmacological agents for prophylaxis would increase the risk of infection following TJA procedures was inconsistent7. The rates of SSC were generally higher in studies with routine pharmacological VTE prophylaxis than those studies in which pharmacological VTE prophylaxis were not routinely administered (0.4–13.3% vs. 1.5–3.6%)17,18,19,20. The rates of PJI were similar between studies with or without routine pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (0.4–1.5% vs. 0.48–1.63%)17,18,19,20. However, the design of these studies were case series lacked a control group. There were only a few studies that compared the risk of infection between patients who received pharmacological prophylaxis and those did not10,11. Parvizi et al.11 and Sachs et al.10 have concluded that the use of low-dose warfarin was associated with a higher risk of wound healing problems or infection, especially in patients who had a mean international normalized ratio greater than 1.511. A meta-analysis by Hughes et al.21 reported similar findings, that the use of warfarin for thromboprophylaxis was associated with a higher risk of SSC and PJI, compared with aspirin. The risk of SSC and PJI were not different between the aspirin and LMWH group21. Runner et al.22 evaluated the complications of 22,072 patients who received different pharmacological agents for thromboprophylaxis. The rates of infection were higher (1.9% vs. 1.3%, p = 0.001) in patients who received more aggressive prophylaxis strategies (e.g., LMWH, warfarin, rivaroxaban, fondaparinux, or others) than the less aggressive strategies (e.g., aspirin or mechanical devices). In this study, despite the fact that a daily dose of LMWH for 3 days and then transitioning to low-dose aspirin for 2 to 5 weeks was considered a less aggressive strategy10,11,21,22, we still observed the association between pharmacological prophylaxis and early postoperative infection events. The postoperative 30 and 90 days were two common time points to evaluate the early postoperative complications, including SSC and PJI23,24,25. Notably, pharmacological thromboprophylaxis was associated with multiple outcome domains in the early postoperative period, including 90-day readmission for SSC, PJI, and all 90-day PJI events. To interpret these results, we might consider pharmacological thromboprophylaxis to have an impact on early postoperative infections rather than to emphasize the effect on a specific form of infection at a certain point of time (e.g., pharmacological thromboprophylaxis as a risk factor for 90-day but not 30-day readmission for PJI).

We have identified several risk factors for SSC and PJI other than VTE prophylaxis, including DM, obesity, underweight, simultaneous bilateral TJA procedure, younger age, male sex and RA. DM is associated with immune system alterations, including impaired leukocyte function, impaired release of inflammatory cytokines in response to infection stimuli26 and enhancing the formation of biofilm27. In our study, DM patients had a 1.6–2.0 times higher risk of SSC than non-DM patients, which was consistent with findings from other studies28,29. Notably, the risk was even higher in patients who had morning hyperglycemia30 and poorly controlled hemoglobin A1c values31, indicating that the risk of SSC in DM patients would still be modifiable. In our study, both obesity and underweight were associated with a higher risk of infection events. Obesity might lead to negative effects on the functions of immune effector cells and the expression of immunomodulatory factors32, poor perfusion and tissue oxygenation33, increased tension on wound edges and dehiscence and impaired tissue penetration of antibiotics34. The poor nutritional and immunocompromised status in the underweight patient might also lead to an increased risk of PJI35. The relationship between BMI and risk of infection was not linear; either a high or a low BMI might be associated with increased infection risk35. We have noted simultaneous bilateral TJA to be a risk factor for PJI, which was consistent with several large-scale studies36,37. However, regarding the risk of infection events, the choice between a staged or simultaneous bilateral TJA procedure remains controversial38,39. Younger age was another risk factor for PJI, which is consistent with the findings from several large-scale studies40,41. Higher activity level, greater number of loading cycles on the implant and increased wear, and prior surgery before TJA might increase the infection risk41,42. We found an association between male sex and PJI, which was also observed in several other studies, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear17,19. The poor nutritional and immunocompromised status of RA patients might lead to an increased risk of PJI18,40, which was consistent with the results of this study. Because of the more liberal criteria for blood transfusion in our study, the overall transfusion rate was high (35.0%). Allogeneic blood transfusion has been reported to be associated with SSC or PJI, possibly due to transfusion-induced immunomodulation43. However, blood transfusion was not a risk factor for SSC or PJI in the univariate or multivariate regression analysis (Tables S1–8).

There were several limitations of this study. First, the study period was 10 years, possible modifications of the perioperative care protocol and surgical techniques could have an impact on the rates of SSI and PJI events. Second, compared with several large-scale studies17,18,19,20, our rates of SSC (1.1%, N = 80) and PJI (0.2%, N = 16) in the early postoperative period were low. Despite the relatively large sample size of this study (N = 7511), the number of SSC and PJI events were small. Third, we evaluated that thromboprophylaxis with a combination of LMWH and low-dose aspirin might be associated with early postoperative SSC and PJI events, but the results of this study might not be generalizable to other medications for thromboprophylaxis. Fourth, this single-surgeon study design could impact the generalizability of the results. Fifth, we should recognize the inherent limitations of the retrospective study design.

Conclusion

Pharmacological thromboprophylaxis appears to be a modifiable risk factor for SSC and PJI in the early postoperative period. In addition to the risk of VTE and bleeding, the increased infection risk should also be carefully evaluated in patients who receive pharmacological VTE prophylaxis.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and available upon request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- DVT:

-

Deep vein thrombosis

- LMWH:

-

Low molecular weight heparin

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- ONFH:

-

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head

- PACU:

-

Post-anesthesia care unit

- PE:

-

Pulmonary embolism

- PJI:

-

Periprosthetic joint infection

- POD:

-

Post-operative day

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SONK:

-

Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee

- SSC:

-

Surgical site complications

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

- TJA:

-

Total join arthroplasty

- TKA:

-

Total knee arthroplasty

- VTE:

-

Venous thromboembolism

References

Falck-Ytter, Y. et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 141(2 Suppl), e278S-e325S (2012).

Mont, M. A. & Jacobs, J. J. AAOS clinical practice guideline: Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 19(12), 777–778 (2011).

Yhim, H. Y., Lee, J., Lee, J. Y., Lee, J. O. & Bang, S. M. Pharmacological thromboprophylaxis and its impact on venous thromboembolism following total knee and hip arthroplasty in Korea: A nationwide population-based study. PLoS ONE 12(5), e0178214 (2017).

Lee, W. S., Kim, K. I., Lee, H. J., Kyung, H. S. & Seo, S. S. The incidence of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis after knee arthroplasty in Asians remains low: A meta-analysis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 471(5), 1523–1532 (2013).

Wu, P. K., Chen, C. F., Chung, L. H., Liu, C. L. & Chen, W. M. Population-based epidemiology of postoperative venous thromboembolism in Taiwanese patients receiving hip or knee arthroplasty without pharmacological thromboprophylaxis. Thromb. Res. 133(5), 719–724 (2014).

Ngarmukos, S. et al. Asia-Pacific venous thromboembolism consensus in knee and hip arthroplasty and hip fracture surgery: Part 1. Diagnosis and risk factors. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 33(1), 18 (2021).

Thiengwittayaporn, S. et al. Asia-Pacific venous thromboembolism consensus in knee and hip arthroplasty and hip fracture surgery: Part 3. Pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 33(1), 24 (2021).

Patel, V. P. et al. Factors associated with prolonged wound drainage after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 89(1), 33–38 (2007).

Agaba, P., Kildow, B. J., Dhotar, H., Seyler, T. M. & Bolognesi, M. Comparison of postoperative complications after total hip arthroplasty among patients receiving aspirin, enoxaparin, warfarin, and factor Xa inhibitors. J. Orthop. 14(4), 537–543 (2017).

Sachs, R. A., Smith, J. H., Kuney, M. & Paxton, L. Does anticoagulation do more harm than good?: A comparison of patients treated without prophylaxis and patients treated with low-dose warfarin after total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 18(4), 389–395 (2003).

Parvizi, J. et al. Does “excessive” anticoagulation predispose to periprosthetic infection?. J. Arthroplasty. 22(6 Suppl 2), 24–28 (2007).

Kim, S. M., Moon, Y. W., Lim, S. J., Kim, D. W. & Park, Y. S. Effect of oral factor Xa inhibitor and low-molecular-weight heparin on surgical complications following total hip arthroplasty. Thromb. Haemost. 115(3), 600–607 (2016).

Cheng, Y. C. et al. Analysis of learning curve of minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty: A single surgeon’s experience with 4017 cases over a 9-year period. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 82(7), 576–583 (2019).

Tsai, S. W. et al. Modified anterolateral approach in minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int. 25(3), 245–250 (2015).

World Health Organization. BMI classification. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi. (Accessed 13 Jan 2022).

Almeida, R. P., Mokete, L., Sikhauli, N., Sekeitto, A. R. & Pietrzak, J. The draining surgical wound post total hip and knee arthroplasty: What are my options? A narrative review. EFORT Open Rev. 6(10), 872–880 (2021).

MAC. Risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection following primary total hip arthroplasty: A 15-year, population-based cohort study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 102(6), 503–509 (2020).

Bozic, K. J. et al. Patient-related risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection and postoperative mortality following total hip arthroplasty in Medicare patients. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 94(9), 794–800 (2012).

Hinarejos, P. et al. The use of erythromycin and colistin-loaded cement in total knee arthroplasty does not reduce the incidence of infection: A prospective randomized study in 3000 knees. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 95(9), 769–774 (2013).

Sezgin, E. A., W-Dahl, A., Lidgren, L. & Robertsson, O. Weight and height separated provide better understanding than BMI on the risk of revision after total knee arthroplasty: Report of 107,228 primary total knee arthroplasties from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 2009–2017. Acta Orthop. 91(1), 94–97 (2020).

Hughes, L. D. et al. Comparison of surgical site infection risk between warfarin, LMWH, and aspirin for venous thromboprophylaxis in TKA or THA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JBJS Rev. 8(12), e20 (2020).

Runner, R. P., Gottschalk, M. B., Staley, C. A., Pour, A. E. & Roberson, J. R. Utilization patterns, efficacy, and complications of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis strategies in primary hip and knee arthroplasty as reported by American Board of Orthopedic Surgery part II candidates. J. Arthroplasty. 34(4), 729–734 (2019).

Park, K. J., Chapleau, J., Sullivan, T. C., Clyburn, T. A. & Incavo, S. J. 2021 Chitranjan S. Ranawat Award: Intraosseous vancomycin reduces periprosthetic joint infection in primary total knee arthroplasty at 90-day follow-up. Bone Joint J. 103-B(6 Supple A), 13–17 (2021).

Mahajan, S. M. et al. Risk factors for readmissions after total joint replacement: A meta-analysis. JBJS Rev. 9(6), e20 (2021).

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI). https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf. (Accessed 24 Apr 2022).

Mor, A. et al. Rates of community-based antibiotic prescriptions and hospital-treated infections in individuals with and without type 2 diabetes: A Danish nationwide cohort study, 2004–2012. Clin Infect Dis. 63(4), 501–511 (2016).

Seneviratne, C. J., Yip, J. W., Chang, J. W., Zhang, C. F. & Samaranayake, L. P. Effect of culture media and nutrients on biofilm growth kinetics of laboratory and clinical strains of Enterococcus faecalis. Arch. Oral Biol. 58(10), 1327–1334 (2013).

Song, K. H. et al. Differences in the risk factors for surgical site infection between total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty in the Korean Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (KONIS). Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 33(11), 1086–1093 (2012).

Qin, W., Huang, X., Yang, H. & Shen, M. The influence of diabetes mellitus on patients undergoing primary total lower extremity arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 6661691 (2020).

Mraovic, B., Suh, D., Jacovides, C. & Parvizi, J. Perioperative hyperglycemia and postoperative infection after lower limb arthroplasty. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 5(2), 412–418 (2011).

Cancienne, J. M., Werner, B. C. & Browne, J. A. Is there a threshold value of hemoglobin A1c that predicts risk of infection following primary total hip arthroplasty?. J. Arthroplasty. 32(9S), S236–S240 (2017).

Jasinski-Bergner, S., Radetzki, A. L., Jahn, J., Wohlrab, D. & Kielstein, H. Impact of the body mass index on perioperative immunological disturbances in patients with hip and knee arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 12(1), 58 (2017).

Fujii, T. et al. Thickness of subcutaneous fat as a strong risk factor for wound infections in elective colorectal surgery: Impact of prediction using preoperative CT. Dig. Surg. 27(4), 331–335 (2010).

Toma, O. et al. Pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of cefoxitin in obesity: Implications for risk of surgical site infection. Anesth. Analg. 113(4), 730–737 (2011).

Berbari, E. F. et al. The Mayo prosthetic joint infection risk score: Implication for surgical site infection reporting and risk stratification. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 33(8), 774–781 (2012).

Panula, V. J. et al. Risk factors for prosthetic joint infections following total hip arthroplasty based on 33,337 hips in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register from 2014 to 2018. Acta Orthop. 92(6), 665–672 (2021).

Pulido, L., Ghanem, E., Joshi, A., Purtill, J. J. & Parvizi, J. Periprosthetic joint infection: The incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 466(7), 1710–1715 (2008).

Makaram, N. S., Roberts, S. B. & Macpherson, G. J. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty is associated with shorter length of stay but increased mortality compared with staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Arthroplasty. 36(6), 2227–2238 (2021).

Huang, L. et al. Comparison of mortality and complications between bilateral simultaneous and staged total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 98(39), e16774 (2019).

Resende, V. A. C. et al. Higher age, female gender, osteoarthritis and blood transfusion protect against periprosthetic joint infection in total hip or knee arthroplasties: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 29(1), 8–43 (2021).

Malinzak, R. A. et al. Morbidly obese, diabetic, younger, and unilateral joint arthroplasty patients have elevated total joint arthroplasty infection rates. J. Arthroplasty. 24(6 Suppl), 84–88 (2009).

Meehan, J. P., Danielsen, B., Kim, S. H., Jamali, A. A. & White, R. H. Younger age is associated with a higher risk of early periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic mechanical failure after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. Am. 96(7), 529–535 (2014).

Taneja, A. et al. Association between allogeneic blood transfusion and wound infection after total hip or knee arthroplasty: A retrospective case-control study. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 4(2), 99–105 (2019).

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F-Y.P., W-L.C. and S-W.T. were responsible for conception and design, publication screening, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, and drafting and revising the manuscript. F-Y.P. and W-L.C. prepared the initial analysis and tables. P-K.W., C-F.C., P-K.W. and W-M.C. were responsible for reviewing and revising the manuscript. All authors were involved with interpretation of the data. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pai, FY., Chang, WL., Tsai, SW. et al. Pharmacological thromboprophylaxis as a risk factor for early periprosthetic joint infection following primary total joint arthroplasty. Sci Rep 12, 10579 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14749-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14749-y

This article is cited by

-

Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index as an effective tool for the choice between simultaneous or staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty

Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery (2024)

-

The impact of Charlson Comorbidity Index on surgical complications and reoperations following simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty

Scientific Reports (2023)