Abstract

In this study, we implemented a system to classify lung opacities from frontal chest x-ray radiographs. We also proposed a training method to address the class imbalance problem presented in the dataset. We participated in the Radiological Society of America (RSNA) 2018 Pneumonia Detection Challenge and used the datasets provided by the RSNA for further research. Using convolutional neural networks, we implemented a training procedure termed batch control to manipulate the data distribution of positive and negative cases in each training batch. The batch control method regulated and stabilized the performance of the deep-learning models, allowing the adaptive sensitivity of the network models to meet the specific application. The convolutional neural network is practical for classifying lung opacities on chest x-ray radiographs. The batch control method is advantageous for sensitivity regulation and optimization for class-unbalanced datasets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung that primarily affects the small air sacs called alveoli, and it is usually caused by bacterial or viral infection. Pneumonia symptoms typically include cough with phlegm, chest pain, difficulty breathing, and fever, and the severity of symptoms can vary. Pneumonia usually manifests as an area or areas of opacity on chest radiographs (CXRs). However, pneumonia diagnosis is complicated because increased opacity on CXRs could represent several other lung conditions, such as pulmonary edema, bleeding, volume loss, and lung cancer.

In recent years, deep-learning methods based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have exhibited increasing potential and efficiency in image recognition tasks, such as robotics1, self-driving cars2,3, and medical applications4,5,6,7. For application to CXR, deep-learning models can achieve detection performance close to that of radiologists8,9. Rajpurkar et al. developed CheXNet10 by using the ChestX-ray14 dataset11, which contains 112,120 frontal-view chest x-ray images individually labeled with 14 different pathologies, including pneumonia. They estimated and compared the performance of the model and four radiologists, revealing that the model exceeded the average performance of the radiologists on the pneumonia detection task. Hwang et al. applied a deep-learning method for chest radiograph diagnosis in the emergency department8, with their results indicating that the diagnostic performance of radiology residents using CXR readings improved after radiographs were reinterpreted through the deep-learning algorithm output.

In the 2018 Radiological Society of America (RSNA) Pneumonia Detection Challenge (https://www.kaggle.com/c/rsna-pneumonia-detection-challenge), 1499 teams participated, 344 teams entered the second stage, and our team “TigerDuck” finished in 22nd place. The short competition period (August 28 to October 31, 2018) did not allow for a thorough performance assessment of this application. After the competition, we further investigated the dataset and CXR models and observed that class imbalance played a major role in the optimization of classification performance. In this study, we investigated the effect of imbalance classification in the CXR deep-learning model and proposed a batch control method (BCM) to regulate the sensitivity of deep learning–based CXR models.

Methods and materials

Datasets

The dataset used for model development and evaluation was obtained from the RSNA Pneumonia Detection Challenge and is part of the ChestX-ray14 dataset, which is publicly available from National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. The dataset consists of the class information, 25,684 frontal-view chest radiographs in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format, and the bounding box information of corresponding labels of different patients. Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of this dataset, and Fig. 1 presents five examples with class and bounding box descriptions. Figure 2 depicts the CXR images and the corresponding labels of the lung-opacity regions. All frontal chest radiographs were annotated by six board-certified radiologists. Three types of classes were identified in a total of 25,684 images, namely lung opacity (5659 images), normal (8525 images), and no lung opacity or not normal (11,500 images). We randomly selected 24,684 images to form a training set and 458 images for a testing set (lung opacity: 229 images; no lung opacity: 229 images). The data distribution is detailed in Table 1.

Images and labels corresponding to the five examples introduced in the Fig. 1.

Deep learning: semantic segmentation and UNet

In this study, we applied semantic segmentation to detect and locate the lung opacities of pneumonia in frontal CXR images (Fig. 3). Semantic segmentation refers to a process of pixel-wise classification of an image, where the boundary and location of target objects are learned pixel by pixel. The general architecture of semantic segmentation can be considered an encoder network followed by a decoder network. The encoder is generally a classification network, which extracts particular features from input images. After several encoder and decoder stages, each pixel of an input image is classified into a specific category.

In our study, the two-dimensional UNet was used for our semantic segmentation approach12. The UNet architecture consists of a contracting path to capture context on the left and an expanding path for precise localization on the right. The contracting path comprises stacks of 3 × 3 convolutional layers; each layer is followed by a rectified linear unit (ReLU function) and a 2 × 2 max-pooling operation with stride = 2 for downsampling. During the enconding stage, the number of CNN filters doubled at each downsampling stage. The expanding path contains the following: (1) an upsampling process of the feature map followed by 2 × 2 upconvolution, which halves the number of feature channels; (2) a concatenation with the corresponding feature map from the contracting path; and (3) two 3 × 3 convolutional layers followed by the ReLU function. Finally, a fully connected layer maps each component feature to the desired classes.

BCM

For machine learning methods, gradient descent is the most widely used algorithm for optimizing CNNs. A batch refers to a group of training samples used in gradient-descent optimization, and depending on the number of samples (i.e., the batch size) in each training step, the following three modes of optimization can be performed: (1) batch mode, where the batch size is equal to the sample size; (2) stochastic mode, where only one sample is used in each training step; and (3) minibatch mode, where the batch size is between the batch and stochastic mode. Batch-mode learning uses the whole training set to obtain a loss value at each training step, consuming considerable computation resources for large datasets. Therefore, minibatch mode learning is generally used for deep-learning applications.

For minibatch gradient-descent optimization, we calculated the sum of gradients with respect to the samples in the minibatch and updated the network parameters by using this cumulative gradient. In general, a minibatch is randomly sampled from the whole dataset, and thus, the distribution of data classes varies in each batch, potentially leading to stochasticity of the obtained model. In this study, we proposed a BCM to manipulate the class distribution of a batch. Using a batch size of six, we altered the number of positive and negative cases in the lung-opacity classification model. Seven schemes of BCMs were used, denoted as P100, P83, P66, P50, P33, P17, and RAND. The corresponding proportions of positive samples were 100%, 83%, 66%, 50%, 33%, 17% and 22%, respectively. For example, a P100 batch contained six positive cases that were randomly selected from the training dataset, whereas a P83 batch contained five positive cases and one negative case. A RAND batch contained six randomly selected samples.

Training, prediction, and evaluation

We trained the proposed UNet with the following parameters: optimizer, Adam; batch size, 6; batch mode, P100, P83, P66, P50, P33, P17, and RAND; loss function, cross-entropy, training steps, 60,000; and image augmentation, random image flipping, rotation angle (15° to − 15°), and contrast adjustments (0.6–1.4). We implemented the UNet structure with a TensorFlow framework (v1.8) and Python (v3.6) environment and trained the model on a personal computer with a graphics processing unit (GPU) (1080 Ti, Nvidia, Santa Clara, CA, USA). We performed eight trials for each data type combination and evaluated the performance of the models with the true-positive rate (TPR; also called sensitivity or recall), the true negative rate (TNR; also called specificity), accuracy (ACC), the false positive rate (FPR), F1-score, and the coefficient of variation of the F1-score (F1-CV).

Results

Figure 4 illustrates examples of the predicted results from the CXR test set. Figures 4a and b demonstrate positive and negative predictions, respectively. The region of lung opacity of true and predicted labels are denoted by the green and red bounding boxes, respectively. In Fig. 4a, all CXR images exhibit red boxes, indicating classification as positive cases by the UNet model. The first two cases were classified as true-positive (TP) observations, and the last two cases were identified as false positive (FP) observations. Only when the green and red boxes overlapped did we designate a TP observation. For the second case, the predicted and true findings were both positive, and the green and red boxes overlapped. Although the model also generated an FP red box (indicated by the yellow arrow), we classified this prediction as a TP case. For the fourth case, although the predicted and true findings were both positive, we defined it an FP case because the predicted region (indicated by the orange arrow) did not overlap with the true region of lung opacity.

Example results of predicted cases, including (a) true positives (TP), (b) false positives (FP), (c) true negatives (TN), and (d) false negatives (FN). The true and predicted lung-opacity regions are denoted by green and red bounding boxes, respectively. Within the definitions of this study, we considered the second example in (a) to be a TP despite one of the two predicted boxes (yellow arrow) not overlapping with the reference box. We regarded the second example in (b) as an FP. Although the CXR model correctly predicted this as positive, the predicted region, indicated by the orange arrow, does not overlap with the green box.

Table 2 lists the quantitative assessment of the CXR models obtained using the seven batch modes. From the P100 to P17 models, the number of positive cases decreased, the average TPR decreased, and the average TNR increased. The P83 model produced the highest F1-score (TPR: 0.80, TNR: 0.75, F1-score: 0.78), whereas the RAND model exhibited low performance (TPR: 0.46, TNR: 0.98, F1-score: 0.62). The F1-CV values (eight trials) of the BCM models ranged from 0.011 to 0.043, and the F1-CV of the RAND model was 0.135. The relatively low F1-CV of the BCM models suggested more stable results than those of the RAND model. In addition to the classification results, we discovered that the segmentation of the lung-opacity regions produced by the RAND model was sometimes tattered, leading to scattered localization of the predicted bounding boxes. Figure 5 presents the predicted results of four samples obtained using the BCM (upper row) and RAND (lower row) models, and Fig. 6 depicts the generated bounding boxes corresponding to Fig. 5. Scattered bounding boxes were visible in the area of true labels in the RAND results. The BCM results obtained from the same images exhibited largely intact bounding boxes. However, the prediction results of the BCM models revealed no such conditions, and the prediction areas were largely intact. The prediction results of BCM presented more complete shapes than those of the RAND model, which exhibited blurred, unclear contours with scattered pixels.

Bounding boxes generated from the batch control method and random models, corresponding to the masks in Fig. 5.

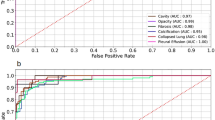

Figure 7 illustrates the TPR values plotted against those of FPR for the six BCM models; the relative trade-offs between TPR and FPR performance exhibited similarity to a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of a binary classifier system with varied thresholds for discrimination. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) provided a joint metric of the prediction performance despite classification thresholds. We linearly interpolated the six TPR–FPR pairs of the BCM models and calculated an analogous AUC value of the UNet CXR model. This value of 0.82 represented the model performance irrespective of which batch mode was chosen.

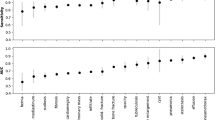

In addition to UNet, we used SegNet13 and PSPNet14 to form a semantic segmentation model. SegNet and PSPNet are widely used methods of semantic segmentation implementation. Overall, the model performance did not vary significantly across the three networks. As with the UNet results, we observed consistent TPR and TNR trends in the six batch modes (data not shown). However, the coefficient of variations in the F1-score identified differences. Figure 8 presents a comparison of the CVs of the F1-score between SegNet, UNet, and PSPNet with the seven batch modes. For the BCM models, the average F1-CV values obtained using SegNet, UNet, and PSPNet were 0.0363, 0.0236, and 0.0345, respectively. For the RAND model, the F1-CV values for the three nets were 0.095, 0.124, and 0.105, respectively. Regardless of the network structure, all BCM models exhibited prominently lower F1-CV scores than the RAND model did. Among the three networks, UNet had the lowest F1-CV values.

Discussion

Imbalanced classification refers to the unequal distribution of data categories in the training dataset of a classification model and is a prevalent problem in data-driven deep-learning models. For example, the COVID-19 outbreak spread worldwide in mere months, affecting the lives and health of countless people. At the beginning of the outbreak, the CXRs of patients with confirmed cases of COVID-19 were available, but attempts to structure a deep-learning CXR model identifying COVID-19 cases with the unbalanced dataset would impede accurate performance assessment of the obtained model. In this study, we investigated BCM as a potential solution to imbalanced classification. The main methodological concept is the regulation of CXR model sensitivity by manipulating the data distribution of the data batches used for the training procedures.

In the dataset, the ratio between positive and negative cases was unbalanced (approximately 1:4). At the beginning of this study, we implemented the UNet model and trained it using a vanilla approach; we shuffled and created random batches of the dataset, fed these batches into the UNet model, and calculated the loss function for minibatch gradient-descent optimization. However, the result obtained in the preliminary stage was unsatisfactory and unstable. We then tailored the BCM to address the class imbalance problem. The BCM manipulates the distribution of positive and negative cases in each batch. For a batch size of six, we altered the number of positive cases from six to one and the number of negative cases from zero to five in each batch to create the P100 to P17 models. The vanilla UNet approach trained with a random data distribution produced the RAND model.

Following the class balanced test set (positive: 229, negative: 229 cases) and eight trials of training procedures, the P83 model (F1: 0.78) outperformed the other six models (F1: 0.62–0.77) in terms of F1-score. The other metrics of the P83 and RAND models were TPR = 0.80, FPR = 0.25, ACC = 0.78, and F1-CV = 0.012 for P83 and TPR = 0.46, FPR = 0.02, ACC = 0.72, and F1-CV = 0.135 for RAND. The F1-score of 0.62 for the RAND (the proportion of positive samples: 22%) approach was between those of the P33 (0.72) and P17 (0.60) models. The results indicate that the F1-scores were associated with the data distribution of training batches. In the three models (P33, P17, RAND), more negative cases were used in each iteration of network optimization. We anticipated that the networks would use a greater proportion of negative samples, which tended to result in more negative predictions. The TPR and FPR values from P100 to P17 were 0.93–0.44 and 0.77 to 0.01, respectively, which validate the association between data distribution and model performance. The results of P83, P66, and P50 presented higher F1-scores (0.75–0.78) than the other model did (0.60–0.72), indicating that the CXR model performed better when more than half of the training batch comprised positive samples. We can regulate the sensitivity of the CXR models by using the BCM to meet the requirements of different clinical environments. For example, if the identification of lung opacities in patients is a primary reason for CXR examination, a P83 BCM model may be suitable.

Across the eight trials of the training–testing procedures, the F1-CV values of the BCM models ranged from 0.011 to 0.043, and those of the RAND model ranged from 0.118 to 0.135, demonstrating that the BCM produced more stable results than did the RAND method. A fixed ratio of positive and negative samples resulted in a smoother loss function and led to better convergence in the BCM models. In our study, we investigated three networks: UNet, SegNet, and PSPNet; most of their performance metrics (e.g., TPR, and FPR) were similar except for the F1-CV. The average F1-CV values of the BCM models were 0.0236 (UNet), 0.0363 (SegNet), and 0.0345 (PSPNet), suggesting that the UNet method was the most stable.

In this study, a batch size of six was used because of the random access memory limit of the GPU (11 gigabytes in the GTX 1080Ti GPU card); therefore, the data distribution of the batch was limited to six variations, P100 to P17. With more GPU RAM, we may further improve the classification performance through the precise adaption of data distributions. For example, the result of P83 (positive:negative, P:N = 5:1) exhibited the best F1-score among the BCM models. We could produce P92 (P:N = 11:1) or P90 (P:N = 9:1) models to further optimize the CXR models. Supplement Fig. 1 displays our preliminary investigations on different batch sizes (batch size = 6, 9, 12, 18) and data ratios (P33, P66, P100). We can regulate the sensitivity of the CXR models by different batch sizes. Increasing the GPU RAM and the combinations in each batch merits further investigation.

In the machine learning methods, the learning procedures are generally biased towards the majority class because the classifiers aim to reduce global loss function. Therefore, the obtained model tends to misclassify the minority class in the dataset. To deal with the class imbalance problems, there exists several approaches in the machine learning field. At the data level, resampling methods, such as over-sampling, under-sampling or SMOTE15,16,17, generate a new dataset with adjusted data distribution. At the algorithm level, advanced loss functions, such as class rectification loss18 and focal loss19, taking the data distribution into loss derivation have been shown effective in the class imbalance problems. The BCM method proposed in this study can be considered as an implementation of the over-sampling method. The BCM method adjusts the proportion of positive samples in a batch and manipulates the over-sampling ratio during the training process. Combining the BCM method with advance loss functions may produce improved performance of the CXR models. Supplement Table 1 lists our preliminary comparison of cross-entropy loss and focal loss. The results suggested that RAND models trained with focal loss prominently improved the metrics of CXR classification. Future studies are necessary to validate the efficacy of the combined methods.

We used the segmentation network UNet for the classification application. The UNet architecture was used for the implementation of an encoder–decoder network with skip connections. In the field of deep learning–based pattern recognition, image classification can be also achieved with the encoder alone, followed by a fully connected output such as VGG1620, ResNet21, or DenseNet22. In addition, object-detection networks such as Faster Region-based CNN (R-CNN)23, YOLO24, or Mask R-CNN25 can be applied to CXR classification problems. We have not implemented or evaluated the BCM with these network architectures; this drawback is a limitation of this study. Nonetheless, we expect the BCMs to be advantageous because they are all based on convolutional networks. Further investigation of this theory is warranted.

In conclusion, we presented the deep-learning method as employed in the RSNA challenge for CXR recognition. To address the class imbalance of the RSNA dataset, we developed and evaluated the BCM. The models obtained using the BCM were more stable, and the sensitivity was adjustable through the manipulation of the distribution of positive and negative cases. Therefore, BCM is a practical method of producing regulable and stable CXR models regardless of whether the training dataset is imbalanced. The rapidly increasing number of confirmed COVID-19 infections continues to exert pressure on medical care systems and exhaust medical resources. As medical science researchers, we believe that global collaborative and investigative efforts will assist in overcoming this catastrophe.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the 2018 Radiological Society of America (RSNA) Pneumonia Detection Challenge, [https://www.kaggle.com/c/rsna-pneumonia-detection-challenge].

References

Algabri, R., Choi, M. T. Deep-learning-based indoor human following of mobile robot using color feature. Sensors, 20(9) (2020).

Chen, C., Liu, B., Wan, S., Qiao, P. & Pei, Q. An edge traffic flow detection scheme based on deep learning in an intelligent transportation system. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 22(3), 1840–1852 (2021).

Kang, Y., Yin, H. & Berger, C. Test your self-driving algorithm: An overview of publicly available driving datasets and virtual testing environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 4(2), 171–185 (2019).

Ehteshami Bejnordi, B. et al. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning algorithms for detection of lymph node metastases in women with breast cancer. JAMA 318(22), 2199–2210 (2017).

Hwang, E. J. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning-based automated detection algorithm for major thoracic diseases on chest radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open. 2(3), e191095 (2019).

Park, S. H. & Han, K. Methodologic guide for evaluating clinical performance and effect of artificial intelligence technology for medical diagnosis and prediction. Radiology 286(3), 800–809 (2018).

Esteva, A. et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 25(1), 24–29 (2019).

Hwang, E. J. et al. Deep learning for chest radiograph diagnosis in the emergency department. Radiology 293(3), 573–580 (2019).

Rajpurkar, P. et al. Deep learning for chest radiograph diagnosis: A retrospective comparison of the CheXNeXt algorithm to practicing radiologists. PLoS Med. 15(11), e1002686 (2018).

Rajpurkar, P., Irvin, J., Zhu, K., et al. CheXNet: Radiologist-level pneumonia detection on chest X-rays with deep learning. (2017).

Wang, X., Peng, Y., Lu, L., et al. ChestX-Ray8: Hospital-scale chest X-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 3462–3471 (2017).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P., Brox, T. J. A. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. MICCAI. 2015;abs/1505.04597 (2015).

Badrinarayanan, V., Kendall, A. & Cipolla, R. SegNet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE T Pattern Anal. 39(12), 2481–2495 (2017).

Zhao, H., Shi, J., Qi, X., Wang, X., Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. Paper Presented at: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 21–26 July 2017, (2017).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Kegelmeyer, W. P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Drummond, C., Holte, R. C. C4. 5, class imbalance, and cost sensitivity: Why under-sampling beats over-sampling. Paper Presented at: Workshop on Learning from Imbalanced Datasets II (2003).

Maciejewski, T., Stefanowski, J. Local neighbourhood extension of SMOTE for mining imbalanced data. Paper Presented at: 2011 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Data Mining (CIDM) (2011).

Dong, Q., Gong, S. & Zhu, X. Imbalanced deep learning by minority class incremental rectification. IEEE T Pattern Anal. 41(6), 1367–1381 (2018).

Lin, T.-Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K., Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. Paper Presented at: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision2017. (2017).

Domingues, I. et al. Using deep learning techniques in medical imaging: A systematic review of applications on CT and PET. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53(6), 4093–4160 (2020).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.902016 (2016).

Iandola, F., Moskewicz, M., Karayev, S., Girshick, R., Darrell, T., Keutzer, K. Densenet: Implementing efficient convnet descriptor pyramids. arXiv preprint arXiv:14041869. (2014).

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE T Pattern Anal. 39(6), 1137–1149 (2017).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R., Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. Paper presented at: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 27–30 June 2016, (2016).

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár,P., Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 107-2314-B-011-002-MY3). We are grateful to the National Center for High-Performance Computing for their assistance and provision of their facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I. C. and T. H. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, IY., Huang, TY. Deep learning-based classification for lung opacities in chest x-ray radiographs through batch control and sensitivity regulation. Sci Rep 12, 17597 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22506-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22506-4

This article is cited by

-

CheXNet and feature pyramid network: a fusion deep learning architecture for multilabel chest X-Ray clinical diagnoses classification

The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging (2023)