Abstract

A series of Aux/TiO2 nanoparticles (NPs) with different gold loadings (x = 0.1–1.0 wt%) was synthesized by the photodeposition and then employed as photocatalysts to recover precious component from the industrial gold-cyanide plating wastewater. Effects of Au loading, catalyst dosage and types of hole scavenger on the photocatalytic gold recovery were investigated under ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) light irradiation at room temperature. It was found that different Au loadings tuned the light absorption capacity of the synthesized photocatalysts and enhanced the photocatalytic activity in comparison with the bare TiO2 NPs. The addition of CH3OH, C2H5OH, C3H8O, and Na2S2O3 as a hole scavenger significantly promoted the photocatalytic activity of the gold recovery, while the H2O2 did not. Among different hole scavengers employed in this work, the CH3OH exhibited the highest capability to promote the photocatalytic gold recovery. In summary, the Au0.5/TiO2 NPs exhibited the best photocatalytic activity to completely recover gold ions within 30 min at the catalyst dosage of 0.5 g/L, light intensity of 3.20 mW/cm2 in the presence of 20 vol% CH3OH as hole scavenger. The photocatalytic activity slightly decreased after the 5th cycle of recovery process, indicating its high reusability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to a fast development of communication and informative technology in our country together with the launch of 5G technology, and also the increasing demand of electronic devices, it is expected that the printed circuit board manufacturing industry will continuously grow during 2021–20231. To prepare the surfaces of electrical contacts and the wire bonding pads of semiconductor devices, the gold plating is widely carried out due to the excellent properties of metallic gold including high electrical conductivity, high reliability, and high corrosion resistance2,3. Through the gold deposition is effectively formed on the nickel-phosphorous (Ni–P) coating deposited on copper (Cu) surface, the plating solution is generally unstable due to the presence of reductant. Thus, the potassium dicyanoaurate (K[Au(CN)]2) is usually used as the gold precursor because of its high stability and capability to form an excellent gold film2,4,5,6. Therefore, the wastewater generated from this process contains high content of gold-cyanide complexes as well as the chemicals used in the surface preparation process. Discharging of precious metal such as gold is an economic loss. Thus, this wastewater is conducted to recover gold by electrolysis and ion exchange process6. However, both processes are expensive and require precise control. Therefore, many processes have been developed and applied to recover gold from the gold-containing wastewater such as electrochemical process7,8,9,10, solvent extraction11,12, and adsorption13,14,15.

Another promising process that can be used to recover gold from the gold-cyanide plating wastewater is the photocatalytic process because of its environmentally friendly, ease of operation and control and able to operate at ambient condition with low operating cost16,17. This process does not require the external supplied electricity and electrodes like an electrochemical process, not require specific extractant like a solvent extraction and not require high surface containing adsorbents like the adsorption. This process can be taken place in the presence of irradiated light, that has the photon energy equal or greater than its band gap energy (Eg)18,19. Then, an electron (e−) is excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), leaving a positive hole (h+) (reaction (R1)). In the presence of gold-cyanide complexes, the deposition of metallic gold on the photocatalyst surface will occur simultaneously with the release of free cyanide ions 6 as expressed by reactions (R2) and (R3). The gold recovery rate from the [Au(CN)2]− is generally sluggish due to its low reduction potential (− 0.57 V/NHE)6. Therefore, many strategies have been carried out to recover gold from the gold-cyanide containing solution via the use of different photocatalysts as well as different operating conditions.

Recently, it was reported that the TiO2/GrSiO2 exhibited the photocatalytic activity to remove gold ions from gold-cyanide plating solutions higher than the bare TiO26. The release of free cyanide ions from the stable metal cyanocomplexes can be achieved by an increase in the availability of cyanide for the subsequent oxidation treatment. The presence of hole scavenger such as methanol (CH3OH) can promote the deposition of metallic Au NPs on the surface of utilized photocatalysts. The use of ZnS can induce the reduction of the gold-cyanide complexes as well as the reverse oxidation of gold NPs via the photogenerated holes at VB20. Approximately 38% of gold was recovered within 120 min via the use of Na2SO3 as the hole scavenger. The ZnO photocatalyst exhibited a high selectivity to recover gold ions from the potassium gold-cyanide wastewater due to its appropriate VB position21. The crystalline quality of the ZnO nanopowder affected positively the efficiency of gold recovery. A complete gold recovery can be achieved with 30 min in the presence of 10 vol% CH3OH. The interaction between the rGO and TiO2 in the rGO/TiO2 composite can alleviate the rate of electron–hole (e−–h+) recombination and enhance the charge transfer between RGO and TiO2 structure, thus promoting the photocatalytic gold recovery from the gold-cyanide complex solution 22. Based on mentioned above, it can be noted the photocatalytic activity of gold recovery depeneds upon various parameters, particularly the photocatalyst type, band position and hole scavenger.

In this work, a series of Aux/TiO2 was synthesized via the photodeposition using the commercial TiO2 as based material. Effects of gold loading on morphology and optical property of the obatined Aux/TiO2 NPs as well as the photocatalytic acitivity for gold recovery from the industrial plating wastwater were explored. The optimum hole scavenger type and catalyst dosage were also determined.

Methods

Property of utilized gold-cyanide plating wastewater

The utilized gold-cyanide plating wastewater was generously offered from the circuit board industry located in Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Thailand. This solution has a light-green clear color with the pH of 8.4–9.2. It contains high concentration of Au ions (10–15 mg/L) and a trace quantity of Cu, Ni, potassium (K), zinc (Zn) of less than 0.06, 0.46, 202.85 and 2.17 mg/L, respectively.

Photocatalyst preparation and characterization

Gold nanoparticles at different contents (0.1–1.0 wt%) were deposited on the surface of commercial TiO2 (99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) by the photodeposition using the chloroauric acid (99.9% HAuCl4·3H2O; Sigma-Aldrich) as the chemical precursor. Briefly, approximately 1.2 g of TiO2 (99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) were dispersed in the 300 mL of 5 mg/L HAuCl4 solution in a double wall cylindrical glass reactor. The pH of the HAuCl4 solution was adjusted to 10 by 0.5 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH; Sigma-Aldrich). The glass reactor was then put on the hotplate stirrer (MSH-300, Biosan) and placed centrally in the UV-protected box. The external cold water was supplied to the jacket of the glass reactor and circulated for the whole experimental time to control the operating temperature (~ 30 °C). A solid–liquid mixture was constantly stirred at the rate of 400 rpm in the absence of light for 30 min to allow a good adsorption of gold ions on the surface of TiO2 NPs. Afterward, a high-pressure mercury lamp (400 W; RUV 533 BC, Holland) was turned on to generate the UV–visible light at the wavelength of 100–600 nm. The incident light intensity at the reactor was kept constantly at around 3.20 mW/cm2. When a complete photodeposition was achieved (~ 1 h), the solid NPs was first separated from a solid–liquid mixture by centrifugal at 11,000 rpm (Eppendorf, 5804R) and washed thoroughly with deionized (DI) water. The ready-to-use Au0.1/TiO2 NPs was obtained after drying at 80 °C for 3 h. The similar procedure was carried out to prepare Au0.3/TiO2, Au0.5/TiO2 and Au1.0/TiO2 via the use of HAuCl4 solution at gold ion concentrations of 15, 25 and 50 mg/L, respectively.

The morphology and optical property of all synthesized Aux/TiO2 NPs as well as the TiO2 were characterized as following. XRD patterns were taken on a Bruker D2 Phaser diffractometer using Cu Kα X-ray). The anatase fraction and average crystallite size of all photocatalyst NPs were computed via Spurr and Myers equation (Eq. 1) and Debye–Scherrer equation (Eq. 2), respectively23.

where xA is the anatase weight fraction, IA is the relative reflection intensities of anatase and IR is the relative reflection intensities of rutile.

where D is the average crystallite size (nm), λ is the wavelength of the X-ray radiation (0.154178 nm), β is the full width at half maximum intensity of the peak and θ is the diffraction angle.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was carried out via a JSM-IT500HR and equipped with a JED-2300 energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrometer at landing voltage of 15.0 kV and magnification × 3000. The content of metallic Au NPs on TiO2 was examined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, PerkinElmer, NexION 2000) using hydrochloric acid (37% HCl, Merck) and nitric acid (68% HNO3, BDH) at volume ratio of 3:1 as extractant. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was taken via a JEM-3100F with an accelerating voltage of 300 kV. XPS data were harvested from Axis Supra+ (Kratos, UK) with a Delay Line detector (DLD) and a monochromatic Al Kα (hν = 1,486.6 eV) source. The spectra were calibrated with the C1s peak of adventitious carbon at binding energy of 284.8 eV to minimize the error of binding energies within the range of ± 0.1 eV. The UPS mode of this analysis allowed to estimate the value of Fermi edge energy (Ef) and cutoff edge energy (Ec), which can be used to compute the photocatalytic work function (Φ) as well as the valence band energy (Ev) and conduction band energy (Ec) according to Eqs. (3)–(5)24,25,26.

where Φ is the work function of photocatalysts, hv is the excitation source which equals to 21.2 eV for helium (He), Ef is the Fermi edge energy, Ec is the cutoff edge energy, EV is the valence band energy, EC is the conduction band energy, Ea is the electron affinity of TiO2 NPs (3.9 eV27) and Eg is the band gap energy obtained from UV–Vis analysis and Tauc’s plot.

N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms were detected using a Multipoint Surface Area Analyzer (Tristar II3020, Micromeritics) via the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. The photoluminescence (PL) data were taken on a Perkin-Elmer LS-55 Luminescence Spectrometer in air at ambient temperature with a 290 nm cut-off filter. The PL signals were collected in the range of 350–550 nm using a standard photomultiplier. UV–Vis absorption spectra were monitored over the wavelength range of 200−800 nm via a Cary300 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent).

Photocatalytic activity of Aux/TiO2 for gold recovery

The experimental set up for testing the photocatalytic activity of the synthesized Aux/TiO2 NPs for gold recovery from gold-cyanide plating wastewater was similar to the previous section. That is, approximately 0.6 g of respective Aux/TiO2 was dispersed in 300 mL of gold-cyanide plating wastewater in the presence of selected hole scavengers including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, BDH Laboratory), sodium thiosulphate (Na2S2O3, KemAus), methanol (CH3OH, QReC), ethanol (C2H5OH, QReC), n-propanol (n-C3H8O, KemAus), i-propanol (i-C3H8O, QReC) and glycerol (C3H8O3, KemAus). The solid–liquid mixture was stirred constantly at 300 rpm in dark environment for 30 min to allow a thoroughly dispersion and adsorption of gold complex species on the photocatalyst surface. Then, the system was irradiated by UV–Vis light (100–600 nm) generated by a high-pressure mercury lamp (400 W; RUV 533 BC, Holland). The light intensity was fixed over the whole experimental period at 3.20 mW/cm2. The temperature of the reactor was controlled at 28–30 °C by the water circulation at the reactor jacket using the circulating pump (PMD-0311, Sanso, Japan). As the reaction proceeded, approximately 5 mL of solution was taken at particular time and subjected to centrifuge at 11,000 rpm (5804R, Eppendorf) to separate the solid NPs from solution. The remining concentration of gold ions in solution at particular time was measured by flame atomic absorption spectrometry (Flame-AAS, Analyst 200 + flas 400; Perkin-Elmer). The reduction rate of gold ions from the gold-cyanide plating wastewater was fitted via the Langmuir–Hinshelwood model according to Eq. (6)28.

where C0 is the initial gold ion concentration (mg/L), C is the gold ion concentration at particular time (mg/L), t is the reaction time (min) and k is the first-order reaction rate constant (min−1).

Results and discussion

Morphology and optical property of synthesized Aux/TiO2

To shed some light on the crystallite structure of all Aux/TiO2 photocatalysts, the XRD analysis was first carried out. As depicted in Fig. 1, the XRD pattern of the original TiO2 NPs exhibited the characteristic peaks of anatase at 2θ of 25.3°, 37.8°, 48.0°, 53.9°, 55.1° and 62.7°, relating to the crystal plane of (101), (004), (200), (105), (221) and (204), respectively (JCPDS file no. 21-1272). Besides, it showed the principal characteristic peaks of rutile phase at 2θ of 27.4°, 36.0°, and 41.2°, relating to the crystal plane of (110), (101), and (111), respectively, (JCPDS file no. 21-1276). No characteristic peaks of Au NPs were observed, probably due to the low content and the high dispersion of Au. The anatase/rutile (A/R) ratio of all Aux/TiO2 NPs estimated from the Spurr and Myers equation (Eq. 1) were around 0.83–0.87. Also, the average crystallite size of TiO2 in anatase (A(101)) and rutile (R(110)) phases computed from Debye–Scherrer equation (Eq. 2) were around 21 and 30 nm, respectively. Both A/R ratio and crystallite size of TiO2 deviated very slightly from the original TiO2 NPs, suggesting that the deposition of Au NPs via the utilized procedure did not change the main characteristic of the parental TiO2 NPs.

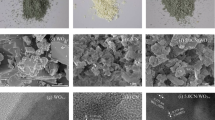

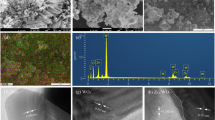

The presence of deposited Au NPs on the surface TiO2 was then explored via the SEM–EDX analysis. As displayed in Fig. 2, a uniform distribution of Au NPs was observed for all loadings. The amount of deposited gold examined by both SEM–EDX and ICP was closed to the preset content as summarized in Table 1. The average particle size of deposited Au NPs was then examined using a high-resolution TEM analysis. As clearly shown in Fig. 3, all HRTEM images showed a clear feature of both TiO2 and Au NPs. The TiO2 NPs exhibited a spherical shape of anatase crystallites (~ 21 nm) and also an angular shape of rutile crystallites (~ 30 nm). The Au NPs exhibited a pseudo-spherical shape with average particle size in the range of 5.8–8.0 nm (Table 1). According to the particle size distribution, it seems to be that the size of Au NPs was largely dependent on the Au loading at low values. That is, the size of Au NPs increased from 5.78 to 7.95 nm as the increase of gold loadings from 0.1 to 0.5 wt% and slightly increased from 7.95 to 8.01 nm as the increase of gold loadings from 0.5 to 1.0 wt%. The size variation of Au NPs on the surface of TiO2 might responsible for the optical property as well as the photocatalytic activity of the Aux/TiO2 photocatalysts.

To probe the presence of chemical elements as well as the oxidation state of gold on the surface of TiO2, the XPS analysis was carried out. As demonstrated in Fig. 4a, the survey XPS showed the intensive peaks of Ti2p and O1s of Ti and O species at binding energy of around 458.3 and 530.2 eV, respectively. The high resolution XPS spectra of Ti2p components in the parental TiO2 structure exhibited two symmetric spectra at binding energy of 458.3 and 464.1 eV (Fig. 4b), corresponding to the spin-orbital doublet of the Ti2p3/2 and Ti2p1/2 components29,30, which indicates the presence of Ti4+ species in TiO2 NPs31. The Ti2p XPS spectra of Aux/TiO2 NPs also revealed the symmetric spectra of Ti2p3/2 and Ti2p1/2 components without any shifting of binding energy compared with those of parental TiO2 NPs. This suggested that the addition of Au NPs on the surface of TiO2 by the photodeposition cannot enhance the formation of the disorder and/or defective structure of TiO2. The Au4f XPS spectra of all Aux/TiO2 NPs showed the core-level electrons at binding energy of ~ 82.9 and ~ 86.5 eV, respectively (Fig. 4c), assigning to the Au4f7/2 and Au4f5/2 of metallic gold 32,33. The intensity of core-level features increased linearity as the increasing gold loading. The Au4f spectra of gold ions were not detected, suggesting that the original gold ions in gold chloride precursor were completely reduced to metallic gold via the photodeposition.

Regardless the textural property of all synthesized samples, the N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of all synthesized Aux/TiO2 NPs together with the parental TiO2 NPs were examined and displayed in Fig. 5. All synthesized samples exhibited the Type IV adsorption/desorption isotherm according to the classification of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). The presence of the H4-hysteresis loop was also observed for all samples, indicating the formation of the slit-like porous structures34. The variation of adsorbed quantity as a function of pore width during 1.48–14.76 nm was also shown as the inset of Fig. 5. Within this pore width range, all Aux/TiO2 NPs exhibited a larger adsorbed quantity than the parental TiO2 NPs. Quantitatively, the BET surface area and total pore volume of all Aux/TiO2 were summarized in Table 1. The Au1.0/TiO2 exhibited the BET surface area slightly higher than that of other Aux/TiO2 NPs as well as the parental TiO2, probably due to its well dispersion on the surface of TiO226,35, which can enhance a high adsorption capacity.

The qualitative recombination rate of e−–h+ pairs was then determined using the photoluminescence (PL) spectrometer. An intense peak of PL signal indicates a high recombination rate of e−–h+ pair. From the plot, the TiO2 NPs revealed three highly broad PL emission peaks, centered at 422.5, 484.0 and 528.0 nm (Fig. 6), indicating a fast e−–h+ recombination. A high-energy spectrum at 422.5 nm is associated from the band edge excitation of TiO2, other spectra are attributed to the electron transition by the state of oxygen vacancies and/or defective structure36,37. All Aux/TiO2 NPs showed lower intense PL spectra than those of TiO2 NPs, indicating that the presence of Au NPs can suppress the rate of e−–h+ recombination. Among all Aux/TiO2 NPs, the intensity of PL spectra decreased as the increase of gold loading (inset of Fig. 6). This can be explained in terms of the charge separation at Schottky junction and the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) phenomenon of Au NPs38. High deposited gold may function as the electron sink, allowing the migration and movement of electrons from the surface to the bulk which consequently promote the e−–h+ separation as well as suppress the e−–h+ recombination39.

To further explore the optical property of all synthesized samples, the light absorption capacity of all synthesized Aux/TiO2 NPs as well as the parental TiO2 was then analyzed. As illustrated in Fig. 7a, the parental TiO2 NPs exhibited a strong absorbance during the ultraviolet (UV) light regime (λ < 400 nm) due to its visible light inertness in nature. All Aux/TiO2 NPs exhibited strong absorption spectrum in the visible light region (λ > 400 nm) with the broad absorption features ~ 540–570 nm, assigning to the LSPR behavior of deposited Au NPs33. The intensity of LSPR peaks increased as the increase of nominal gold loading up to 0.5 wt% and dropped slightly afterward (inset of Fig. 7a). A high light absorption might enhance the harvesting of incident light and also promote the photocatalytic activity. Slight red-shift in the plasmon position was observed with the increased nominal gold loading due to the size increase of Au NPs40. Tauc plots or plots of (αhν)1/n versus photon energy (E) computed from the UV–Vis absorption spectra (Fig. 7a) are shown in Fig. 7b. The Eg of each sample can be obtained by extrapolation the linear portion of this plot to intercept the x-axis. As summarized in Table 1, the Eg energy of TiO2 decreased importantly from 3.35 to 3.22 eV with addition of Au NPs.

Figure 8a illustrates the intensity-kinetic energy plots of commercial TiO2 and all synthesized Aux/TiO2 NPs. Values of Ef and Ec taken respectively from the x-axis interception at high- and low binding energies of this plot are summarized in Table 1. Both obtained energy values were then used to compute the Φ as well as the EV and EC according to Eqs. (3)–(5). It was obtained that the Φ of TiO2, Au0.1/TiO2, Au0.3/TiO2, Au0.5/TiO2 and Au1.0/TiO2 NPs could be determined to be 6.38, 6.23, 6.20, 6.14 and 6.25 eV, respectively. Figure 8b represents the briefly sketch of band position of all synthesized Aux/TiO2 and commercial TiO2 NPs. It is noteworthy that both synthesized Aux/TiO2 and the parental TiO2 NPs had a more negative conduction band level than the reduction potential of [Au(CN)2]−, indicating their ability to act as the photocatalyst for gold reduction from the gold-cyanide plating wastewater.

Photocatalytic activity of Aux/TiO2 for gold recovery

Effect of Au loading on TiO2 NPs

The effect of gold content (0.1–1.0 wt%) deposited on the surface of TiO2 was first explored for the photocatalytic gold recovery from the gold-cyanide plating wastewater at the photocatalyst dosage of 2 g/L and light intensity of 3.20 mW/cm2 in the absence of hole scavenger. As shown in Fig. 9, the concentrations of gold ions did not change at particular time in the presence of TiO2 NPs, while it decreased significantly in the presence of Aux/TiO2 NPs. Among all Aux/TiO2 samples, the Au0.5/TiO2 NPs can achieve a high reduction of gold ions from the plating wastewater. This indicated that the Au0.5/TiO2 exhibited the highest photocatalytic activity for gold recovery from the plating wastewater. Its apparent rate constant estimated from the Langmuir–Hinshelwood model (Eq. 6) was found to be at 0.0190 min−1, which was higher than those of TiO2, Au0.1/TiO2, Au0.3/TiO2, and Au1.0/TiO2 for 38.8, 2.1, 1.4 and 1.6-fold, respectively.

Taking into account the morphology and optical property of all photocatalysts, it can be seen that the variation trend of the photocatalytic activity of all photocatalysts did not correlate with the content or size of deposited gold NPs, height of PL spectra as well as the total pore volume (Table 1). However, it slightly changed corresponding to the variation of the Eg and height of LSPR peak. That is, the Au0.5/TiO2 NPs exhibited the lowest Eg of 3.22 eV and the highest height of LSPR peak and also depicted the highest photocatalytic gold recovery from the gold-cyanide plating wastewater. Interestingly, although the Au1.0/TiO2 NPs showed the lowest PL spectra, comparable Eg to Au0.3/TiO2 and comparable LSPR peak height to Au0.5/TiO2, it showed lower the photocatalytic activity for gold recovery than both Au0.3/TiO2 and Au0.5/TiO2 NPs. This might be due to its high deposited gold content that allowed a freely transfer of excited electron along the bulk phase of gold structure and thus in turn slowdown the photocatalytic activity due to their function as an electron sink39. Another possible reason might be due to the synergetic effect of electron transfer between the anatase, rutile and metallic gold33. That is, a high gold content can randomly deposit on the anatase–rutile interface and also on the isolated anatase or rutile crystallite. The former gave the positive effect to the photocatalytic of Aux/TiO2 NPs, while the latter gave the negative effect33. A high gold content probably induced a high proportion of Au/rutile, which consequently suppressed the photocatalytic activity of Aux/TiO2 NPs. Besides, a high gold loading might form the shadowing behavior, thus preventing the absorption of incident light of the photocatalyst NPs33,41.

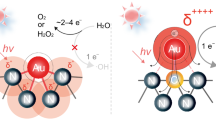

Effect of hole scavengers

Since the photocatalytic recovery of gold from gold-cyanide plating wastewater is impelled by the photogenerated e−, a rapid recombination of photogenerated h+ and e− may suppress the photocatalytic activity. To extend the lifetime of e−–h+ pairs, the removal of photogenerated h+ from the photocatalyst was carried out by introduction of sacrificial hole scavengers to the plating wastewater. In this part, three types of hole scavengers including H2O2, Na2S2O3 and CH3OH were first employed at identical quantity of 20 vol%. The variations of gold recovery via Au0.5/TiO2 photocatalyst at dosage of 2 g/L and light intensity of 3.20 mW/cm2 in the presence of different hole scavengers were depicted in Fig. 10. The addition of H2O2 did not promote the photocatalytic gold recovery via the utilized photocatalyst, while the addition of Na2S2O3 and CH3OH encouraged the photocatalytic rate of gold recovery. The apparent rate constants of the system using Na2S2O3 and CH3OH were 0.0688 min−1 and 0.1332 min−1 which were higher than that in the absence of hole scavenger of 3.6- and 7.0-fold, respectively.

The different photocatalytic activity of each hole scavenger might be attributed to the formation of different ionic species when the hole scavengers reacted with the photogenerated hole42. That is, the active form of hole scavenger in the presence of H2O2 was the OH−, which is coming from the reaction of H2O2 via the incident light or the photogenerated e− according to reactions (R4)–(R6)43,44. Based on these reactions, the use of H2O2 as the hole scavenger consumes the photogenerated e− competitively with the photocatalytic reduction of gold ions to metallic Au NPs, which may suppress the photocatalytic gold recovery of Aux/TiO2 NPs. Besides, the lack of photocatalytic gold recovery in the presence of H2O2 might be originated from its fast decomposition to H2O and O2, which can be experimentally observed immediately after the addition of this hole scavenger. A low photocatalytic activity in the presence of H2O2 as the hole scavenger was also observed for the H2 production via the TiO2 nanotubes45.

Via the Na2S2O3, the thiosulphate ions ((S2O3)2−) can react with the photogenerated h+ at the VB position to form (S4O6)2− according to reaction (R7)46. For comparison, when CH3OH reacted with the photogenerated holes in the Au0.5/TiO2 NPs, the methoxy radicals (CH3O·) may form according to reaction (R8)37,42. These generated radicals can effectively supply electrons to the catalyst surface due to its low standard reduction potential (reaction (R9))47,48, thus promoting the reduction of the adsorbed gold-cyanide species.

The effect of alcohol types including CH3OH, C2H5OH, n-C3H8O, i-C3H8O and C3H8O3 on the photocatalytic gold recovery via Au0.5/TiO2 photocatalyst was further explored at identical quantity of 20 vol% using the photocatalyst dosage of 2 g/L and light intensity of 3.20 mW/cm2. As shown in Fig. 11, the positive effect of hole scavenger on the photocatalytic gold recovery can be ranked as the order of CH3OH > C3H8O > C2H5OH > n-C3H8O > i-C3H8O. This is probably due to the effect of their different oxidation potentials. That is, the driving force of hole scavenging is dictated by the oxidation potential of the hole scavenger molecules45. The chemicals with low oxidation potential thermodynamically exhibits a rapid hole scavenging and vice versa37,45. Based on the obtained results, this fact is mostly conformed for the CH3OH (0.016 V/NHE), C2H5OH (0.084 V/NHE), n-C3H8O (0.100 V/NHE) and i-C3H8O (0.105 V/NHE)37, except the C3H8O (0.004 V/NHE). Although CH3OH has the oxidation potential four times higher than that of C3H8O8, it exhibited a higher positive effect on the photocatalytic gold recovery. This might be due to the electron dissemination of the generated CH3O· radicals according to reaction (R9), which then reduce the adsorbed gold-cyanide species to metallic Au NPs. Interestingly, the system with i-C3H8O exhibited an extremely low gold reduction during the first 90 min although its oxidation potential is slightly lower than that of n-C3H8O. This might be attributed the effect of the molecular steric hindrance of this branched alcohol. That is, a high quantity of i-C3H8O at the early reaction period may obstruct each other to react with the photogenerated h+, thus lower the photocatalytic activity. However, as the time proceeded, part of this alcohol was consumed. Therefore, the photocatalytic activity increased due to the lessening of the steric hindrance effect. Based on the obtained results and literature6,37,42,49, the mechanism of photocatalytic gold recovery from the gold-cyanide plating wastewater on the Au/TiO2 NPs in the presence of CH3OH was roughly sketched as illustrated in Fig. 12.

Effect of catalyst dosage

The effect of photocatalyst dosage (0.5–2.0 g/L) on the photocatalytic gold recovery was then examined at light intensity of 3.20 mW/cm2 in the presence of 20 vol% CH3OH. As displayed in Fig. 13, approximately 93% of gold ions was recovered within 15 min via the use of 0.5 g/L of Au0.5/TiO2 NPs, while greater than 98% was recovered via the same photocatalyst at the dosage of 1.0–2.0 g/L at the same time. A low photocatalytic activity to recover gold at low photocatalyst dosage might be due to the limitation of active site to proceed the photoreaction. Nevertheless, too high photocatalyst dosage also exhibited a low photocatalytic activity due to the light scattering effect as described by Beer-Lambert Law and also the light attenuation due to the self-shading behavior50,51. Thus, it can be noted that the optimum dosage of Au0.5/TiO2 NPs for the photocatalytic gold recovery from the spent gold-cyanide plating wastewater was 1.0 g/L.

Table 2 summarizes the comparative photocatalytic gold recovery from the gold-cyanide containing solution between this work and previous works. It is worth noting that the Au0.5/TiO2 photocatalyst synthesized in this work was on par with other previous works. It exhibited a higher photocatalytic activity than TiO252, TiO2/GrSiO26 and ZnS20 and comparable activity with ZnO21. With respect to rGO/TiO2, it is difficult to conclude that which photocatalyst type is better between rGO/TiO2 and Au0.5/TiO2 due to their high different initial gold ions concentration (~ 13.7-fold).

Figure 14 displays the variation of repetitive gold recovery from the gold-cyanide plating wastewater via the Au0.5/TiO2 photocatalyst at loading of 1.0 g/L and light intensity of 3.20 mW/cm2 in the presence of 20 vol% CH3OH as the hole scavenger. After each photocatalytic experiment, the utilized photocatalyst was washed delicately with DI water and dried in air at 80 °C for 3 h and then subjected to the next photocatalytic run. It can be seen that a fast decrease of gold ions was observed for all repetitive runs, indicating a high resuability of the synthesized Au/TiO2 NPs. The normalized concentration of remianing gold ions were around 0.02, 0.021, 0.027, 0.043 and 0.061 after the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th run, respectively. The purple color of the fresh Au0.5/TiO2 NPs intensified with the increasing repetive runs, due to the increasing deposited Au NPs on photocatalyst surface33,53.

The crystallite structure of Au0.5/TiO2 NPs after all repetitive experiments was also analyzed as shown in Fig. 15. The XRD pattern of the Au0.5/TiO2 NPs after the 1st, 3rd and 5th run were still demonstrated the main characteristic peaks of anatase- and rutile phase as described above. Besides, they exhibited the diffraction peaks of Au NPs at 2θ of 38.2, 44.4°, 64.6° and 77.6°, respectively corresponding to the face-centered cubic (FCC) structure of Au NPs at crystal plans of (111), (200), (220) and (311) (JCPDS No. 002-1095). More intense peak height was observed after a high repetitive run. By SEM–EDX analysis, the gold contents on the Au0.5/TiO2 after the 1st, 3rd and 5th run were around 2.18, 4.56 and 7.53 wt%, respectively. Despite the repetitive runs of gold recovery, an intensely uniform dispersion of Au NPs on the TiO2 surface was observed as illustrated in Fig. 16.

As proposed by Grieken et al.6, the deposited Au NPs can be separated from the TiO2 based material by the selective dissolution via (i) the aqua regia to leach metallic Au NPs, yielding the tetrachloroauric acid (HAuCl4) or (ii) hydrofluoric acid (HF) to leach the based catalyst, getting a brown gold power. To achieve the objective related to the gold recovery from industrial gold-cyanide plating wastewater, the selective dissolution of deposited Au NPs from the TiO2 was carried out using aqua regia as the extractant. By ICP analysis, the obtained solution contained gold ions of around 57, 140 and 224 mg/L, which were related to 2.19, 5.14 and 7.96 wt% Au on TiO2 after the 1st, 3rd and 5th run, respectively, consistent with those analyzed by SEM–EDX.

Conclusion

A set of Aux/TiO2 NPs with different Au loadings was prepared via the photodeposition for photocatalytic gold recovery from industrial gold-cyanide plating wastewater. The deposited Au NPs in the investigated range of 0.1–1.0 wt% exhibited the insignificant effect on the A/R ratio, crystalline size of TiO2, surface area, but it affected importantly the size of deposited Au NPs as well as the light absorption capacity. Among all synthesized photocatalysts, the Au0.5/TiO2 NPs exhibited the best photocatalytic activity to recover gold from the industrial gold-cyanide plating wastewater. The addition of Na2S2O3 and C1-C3 alcohol as the hole scavengers promoted the photocatalytic gold recovery over the Au0.5/TiO2 NPs, while the H2O2 did not. Among all employed alcohols, the CH3OH exhibited the highest efficiency to promote the photocatalytic gold recovery. A complete recovery of gold ions can be achieved within 30 min at the photocatalyst dosage of 0.5 g/L, light intensity of 3.20 mW/cm2 in the presence of 20 vol% CH3OH as hole scavenger. The synthesized Au0.5/TiO2 NPs exhibited higher photocatalytic activity for gold recovery from the gold-cyanide containing solution than some photocatalysts in literature6,20,52. A very slight decrease of the photocatalytic gold recovery was observed after the 5th run, indicating its high reusability and high ability to accumulate the metallic Au NPs on its surface. The separation of deposited Au NPs from the used Au/TiO2 photocatalyst can be carried out by the selective dissolution using the chemical extractant. Besides, the repetitively used Au/TiO2 NPs are possibly used as the photocatalysts for other photocatalytic application such as H2 production26,53,54,55,56, but more characterizations and photocatalytic activity tests are required.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Yongpisanphob, W. Industry Outlook 2021–2023: Electronics. (Krungsri Research 2021).

Kato, M. & Okinaka, Y. Some recent developments in non-cyanide gold plating for electronics applications. Gold Bull. 37(1), 37–44 (2004).

Kunarti, E. S., Roto, R., Nuryono, N., Santosa, S. J. & Fajri, M. L. Photocatalytic reduction of AuCl4− by Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanoparticles. Glob. NEST J. 22, 119–125 (2020).

Sharma, R., Kaneriya, R., Patel, S., Bindal, A. & Pargaien, K. Microwave integrated circuits fabrication on alumina substrate using pattern up direct electroless nickel and immersion Au plating and study of its properties. Microelectron. Eng. 108, 45–49 (2013).

Vorobyova, T., Poznyak, S., Rimskaya, A. & Vrublevskaya, O. Electroless gold plating from a hypophosphite-dicyanoaurate bath. Surf. Coat. Technol. 176, 327–336 (2004).

van Grieken, R., Aguado, J., López-Muñoz, M.-J. & Marugán, J. Photocatalytic gold recovery from spent cyanide plating bath solutions. Gold Bull. 38, 180–187 (2005).

Spitzer, M. & Bertazzoli, R. Selective electrochemical recovery of gold and silver from cyanide aqueous effluents using titanium and vitreous carbon cathodes. Hydrometallurgy 74, 233–242 (2004).

Yap, C. & Mohamed, N. An electrogenerative process for the recovery of gold from cyanide solutions. Chemosphere 67, 1502–1510 (2007).

Figueroa, G. et al. Recovery of gold and silver and removal of copper, zinc and lead ions in pregnant and barren cyanide solutions. Mater. Sci. 6, 171 (2015).

Yap, C. Y. & Mohamed, N. Electrogenerative gold recovery from cyanide solutions using a flow-through cell with activated reticulated vitreous carbon. Chemosphere 73, 685–691 (2008).

Aunnankat, K. et al. Application of solubility data on a hollow fiber supported liquid membrane system for the extraction of gold (I) cyanide from electronic industrial wastewater. Chem. Eng. Commun. 209, 1–10 (2022).

Song, Y. et al. Recycling of residual valuable metals in cyanide-leached gold wastewater using the N263-TBP system. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 106774 (2021).

Rakhila, Y. et al. Adsorption recovery of Ag (I) and Au (III) from an electronics industry wastewater on a clay mineral composite. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 26, 673–680 (2019).

Ok, Y. S. & Jeon, C. Selective adsorption of the gold–cyanide complex from waste rinse water using Dowex 21K XLT resin. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 20, 1308–1312 (2014).

Song, Y., Lei, S., Zhou, J. & Tian, Y. Removal of heavy metals and cyanide from gold mine waste-water by adsorption and electric adsorption. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 91, 2539–2544 (2016).

Jalalah, M., Faisal, M., Bouzid, H., Ismail, A. A. & Al-Sayari, S. A. Dielectric and photocatalytic properties of sulfur doped TiO2 nanoparticles prepared by ball milling. Mater. Res. Bull. 48, 3351–3356 (2013).

Fajrina, N. & Tahir, M. A critical review in strategies to improve photocatalytic water splitting towards hydrogen production. Inter. J. Hydrog. Energy 44, 540–577 (2019).

Zhang, F. et al. Recent advances and applications of semiconductor photocatalytic technology. Appl. Sci. 9, 2489 (2019).

Patsoura, A., Kondarides, D. I. & Verykios, X. E. Enhancement of photoinduced hydrogen production from irradiated Pt/TiO2 suspensions with simultaneous degradation of azo-dyes. Appl. Catal. B 64, 171–179 (2006).

Stroyuk, A., Raevskaya, A., Korzhak, A. & Kuchmii, S. Zinc sulfide nanoparticles: Spectral properties and photocatalytic activity in metals reduction reactions. J. Nanopart. Res. 9, 1027–1039 (2007).

Park, S. et al. Photoreaction of gold ions from potassium gold cyanide wastewater using solution-combusted ZnO nanopowders. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 30, 177–180 (2010).

Albiter, E. et al. Enhancing free cyanide photocatalytic oxidation by rGO/TiO2 P25 composites. Materials 15, 5284 (2022).

Khataee, A., Aleboyeh, H. & Aleboyeh, A. Crystallite phase-controlled preparation, characterisation and photocatalytic properties of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J. Exp. Nanosci. 4(2), 121–137 (2009).

Park, Y., Choong, V., Gao, Y., Hsieh, B. R. & Tang, C. W. Work function of indium tin oxide transparent conductor measured by photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 68, 2699–2701 (1996).

Zeng, S., Jia, F., Yang, B. & Song, S. In-situ reduction of gold thiosulfate complex on molybdenum disulfide nanosheets for a highly-efficient recovery of gold from thiosulfate solutions. Hydrometallurgy 195, 105369 (2020).

Kunthakudee, N., Puangpetch, T., Ramakul, P., Serivalsatit, K. & Hunsom, M. Light-assisted synthesis of Au/TiO2 nanoparticles for H2 production by photocatalytic water splitting. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 23570–23582 (2022).

Ratanatawanate, C., Tao, Y. & Balkus, K. J. Jr. Photocatalytic activity of PbS quantum dot/TiO2 nanotube composites. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 10755–10760 (2009).

Martins, P. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of Au/TiO2 nanoparticles against ciprofloxacin. Catalysts 10(2), 234 (2020).

Jedsukontorn, T., Saito, N. & Hunsom, M. Photocatalytic behavior of metal-decorated TiO2 and their catalytic activity for transformation of glycerol to value added compounds. Mol. Catal. 432, 160–171 (2017).

Kunthakudee, N., Puangpetch, T., Ramakul, P. & Hunsom, M. Photocatalytic recovery of gold from a non-cyanide gold plating solution as Au nanoparticle-decorated semiconductors. ACS Omega 7, 7683–7695 (2022).

Jedsukontorn, T., Ueno, T., Saito, N. & Hunsom, M. Narrowing band gap energy of defective black TiO2 fabricated by solution plasma process and its photocatalytic activity on glycerol transformation. J. Alloys Compd. 757, 188–199 (2018).

Lignier, P., Comotti, M., Schüth, F., Rousset, J.-L. & Caps, V. Effect of the titania morphology on the Au/TiO2-catalyzed aerobic epoxidation of stilbene. Catal. Today 141, 355–360 (2009).

Jovic, V. et al. Effect of gold loading and TiO2 support composition on the activity of Au/TiO2 photocatalysts for H2 production from ethanol–water mixtures. J. Catal. 305, 307–317 (2013).

Xiang, Q., Yu, J. & Jaroniec, M. Enhanced photocatalytic H2-production activity of graphene-modified titania nanosheets. Nanoscale 3, 3670–3678 (2011).

Shu, Y. et al. A principle for highly active metal oxide catalysts via NaCl-based solid solution. Chem 6(7), 1723–1741 (2020).

Selvam, K. & Swaminathan, M. Nano N-TiO2 mediated selective photocatalytic synthesis of quinaldines from nitrobenzenes. RSC Adv. 2, 2848–2855 (2012).

Al-Azri, Z. H. et al. The roles of metal co-catalysts and reaction media in photocatalytic hydrogen production: Performance evaluation of M/TiO2 photocatalysts (M= Pd, Pt, Au) in different alcohol–water mixtures. J. Catal. 329, 355–367 (2015).

Feng, C. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of Au/TiO2 nanofibers by precisely manipulating the dosage of uniform-sized Au nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. A 123, 1–9 (2017).

Al-Azri, Z., AlOufi, M., Chan, A., Waterhouse, G. & Idriss, H. Metal particle size effects on the photocatalytic hydrogen ion reduction. ACS Catal. 9, 3946–3958 (2019).

Marchal, C. et al. Activation of solid grinding-derived Au/TiO2 photocatalysts for solar H2 production from water-methanol mixtures with low alcohol content. J. Catal. 352, 22–34 (2017).

Zhang, X., Chen, Y. L., Liu, R.-S. & Tsai, D. P. Plasmonic photocatalysis. Rep. Prog. Phys. 76, 046401 (2013).

Mureithi, A. W., Sun, Y., Mani, T., Howell, A. R. & Zhao, J. Impact of hole scavengers on photocatalytic reduction of nitrobenzene using cadmium sulfide quantum dots. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100889 (2022).

Machulek Jr, A. et al. In Organic Pollutants-Monitoring, Risk and Treatment, Vol. 1 141–166 (InTech London, UK, 2013).

Xin, X. et al. Sulfadimethoxine photodegradation in UV-C/H2O2 system: Reaction kinetics, degradation pathways, and toxicity. J. Water Process Eng. 36, 101293 (2020).

Denisov, N., Yoo, J. & Schmuki, P. Effect of different hole scavengers on the photoelectrochemical properties and photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance of pristine and Pt-decorated TiO2 nanotubes. Electrochim. Acta 319, 61–71 (2019).

Asiri, A. M. et al. Enhanced visible light photodegradation of water pollutants over N-, S-doped titanium dioxide and n-titanium dioxide in the presence of inorganic anions. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 18, 155–163 (2014).

Wu, W. et al. Mechanistic insight into the photocatalytic hydrogenation of 4-nitroaniline over band-gap-tunable CdS photocatalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 19422–19426 (2013).

Jung, B. et al. Photocatalytic reduction of chlorate in aqueous TiO2 suspension with hole scavenger under simulated solar light. Emerg. Mater. 4, 435–446 (2021).

Lee, Y. et al. Photodeposited metal-semiconductor nanocomposites and their applications. J. Mater. 4, 83–94 (2018).

Wang, X., Shih, K. & Li, X. Photocatalytic hydrogen generation from water under visible light using core/shell nano-catalysts. Water Sci. Technol. 61(9), 2303–2308 (2010).

Kisch, H. & Bahnemann, D. Vol. 6 (ed The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters) 1907–1910 (ACS Publications, 2015).

Serpone, N. et al. Photochemical reduction of gold (III) on semiconductor dispersions of TiO2 in the presence of CN− ions: Disposal of CN− by treatment with hydrogen peroxide. J. Photochem. 36, 373–388 (1987).

Dosado, A. G., Chen, W.-T., Chan, A., Sun-Waterhouse, D. & Waterhouse, G. I. Novel Au/TiO2 photocatalysts for hydrogen production in alcohol–water mixtures based on hydrogen titanate nanotube precursors. J. Catal. 330, 238–254 (2015).

Jiménez-Calvo, P., Caps, V., Ghazzal, M. N., Colbeau-Justin, C. & Keller, V. Au/TiO2 (P25)-gC3N4 composites with low gC3N4 content enhance TiO2 sensitization for remarkable H2 production from water under visible-light irradiation. Nano Energy 75, 104888 (2020).

Balsamo, S. A., Sciré, S., Condorelli, M. & Fiorenza, R. Photocatalytic H2 Production on Au/TiO2: Effect of Au photodeposition on different TiO2 crystalline phases. J 5, 92–104 (2022).

Martínez, L. et al. Preparation and photocatalytic activity of Au/TiO2 lyogels for hydrogen production. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2, 2284–2295 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The research work is supported by the Mahidol University for postdoctoral fellowship program (Grant no. MU-PD_2021_10). The author would like to thank the Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Mahidol University for facilities and equipment support. The author also thanks the Mahidol University Frontier Research Facility (MU-FRF) for instrument support and the MU-FRF scientists, Nawapol Udpuay, Dr. Suwilai Chaveanghong and Bancha Panyacharoen for their kind assistance in XRD operation, and Ms.Tiyanun Jurkvon for her kind assistance in the ICP-MS operation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K. and M.H. designed the project, conceived the experiment, N.K. conducted the experiment, P.R. and K.S. supported equipment, N.K. and M.H. analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kunthakudee, N., Ramakul, P., Serivalsatit, K. et al. Photosynthesis of Au/TiO2 nanoparticles for photocatalytic gold recovery from industrial gold-cyanide plating wastewater. Sci Rep 12, 21956 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24290-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24290-7

This article is cited by

-

Rapid organic contaminants removal by Mg-/Fe-based magnetic nanosheets synthesized using the molten salt method

Journal of Analytical Science and Technology (2025)

-

Comprehensive Study on the Recovery of Gold and Copper from Cinder Washing Solution Through Precipitation-Filtration Processes

Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration (2024)

-

Highly efficient ZnO/WO3 nanocomposites towards photocatalytic gold recovery from industrial cyanide-based gold plating wastewater

Scientific Reports (2023)