Abstract

We explored a new artificial intelligence-assisted method to assist junior ultrasonographers in improving the diagnostic performance of uterine fibroids and further compared it with senior ultrasonographers to confirm the effectiveness and feasibility of the artificial intelligence method. In this retrospective study, we collected a total of 3870 ultrasound images from 667 patients with a mean age of 42.45 years ± 6.23 [SD] for those who received a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of uterine fibroids and 570 women with a mean age of 39.24 years ± 5.32 [SD] without uterine lesions from Shunde Hospital of Southern Medical University between 2015 and 2020. The DCNN model was trained and developed on the training dataset (2706 images) and internal validation dataset (676 images). To evaluate the performance of the model on the external validation dataset (488 images), we assessed the diagnostic performance of the DCNN with ultrasonographers possessing different levels of seniority. The DCNN model aided the junior ultrasonographers (Averaged) in diagnosing uterine fibroids with higher accuracy (94.72% vs. 86.63%, P < 0.001), sensitivity (92.82% vs. 83.21%, P = 0.001), specificity (97.05% vs. 90.80%, P = 0.009), positive predictive value (97.45% vs. 91.68%, P = 0.007), and negative predictive value (91.73% vs. 81.61%, P = 0.001) than they achieved alone. Their ability was comparable to that of senior ultrasonographers (Averaged) in terms of accuracy (94.72% vs. 95.24%, P = 0.66), sensitivity (92.82% vs. 93.66%, P = 0.73), specificity (97.05% vs. 97.16%, P = 0.79), positive predictive value (97.45% vs. 97.57%, P = 0.77), and negative predictive value (91.73% vs. 92.63%, P = 0.75). The DCNN-assisted strategy can considerably improve the uterine fibroid diagnosis performance of junior ultrasonographers to make them more comparable to senior ultrasonographers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Uterine fibroids are by far the most common type of benign tumor in women1. Since CT and MRI examinations are costly and cannot be popularized, ultrasonography is currently the first imaging method used for the clinical diagnosis of uterine fibroids, as it possesses high sensitivity and specificity. Nevertheless, the following problems still exist in ultrasound uterine fibroid diagnoses. The first problem is the confusion between subplasmic and giant fibroids and between pelvic and adnexal masses2. Second, the current lack of standardized image acquisition views and the performance differences among types of ultrasound equipment impact the accuracy of fibroid detection. In addition, the accuracy of ultrasound uterine fibroid diagnosis depends on the knowledge and experience of ultrasonographers3.

Deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) based on deep learning (DL) techniques are new computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) tools that enable the automatic capture of targeted areas after training4,5,6,7,8,9. It is well-recognized by both researchers and clinicians that DL methods are already playing a substantial role in radiology because of their powerful image feature extraction capabilities10. DL algorithms for ultrasound image formation are rapidly garnering research support and attention, quickly becoming the latest frontier in ultrasound image formation11. A large number of previous studies on DCNN models based on ultrasound images mainly focused on the diagnosis of benign and malignant masses in superficial organs, such as the thyroid gland12,13,14,15 and breasts16,17,18,19. However, the diagnosis level of junior ultrasonographers with the assistance of this model has not only reached that of senior ultrasonographers but has also shortened the required diagnosis time. Deeper organs, such as the uterus, have been less studied. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a uterine fibroid detection DCNN model based on DL algorithms.

In this study, to improve the accuracy of ultrasound diagnosis for uterine fibroids, we developed a DCNN model that automates the detection of uterine fibroids in ultrasound images and discriminates between the presence and absence of fibroids and internally and externally validated the model. We also compared the DCNN model against eight ultrasonographers with different levels of seniority and explored whether the diagnostic performance of junior ultrasonographers can be improved with the assistance of this DCNN model.

Methods

Study patients and images

In this retrospective, noninterventional, case‒controlled study, we collected ultrasound images of patients who had been diagnosed with uterine fibroids according to surgical and pathological findings and those with normal uteri. Using these ultrasound images, we developed a DCNN model to automatically detect uterine fibroids in the images and to assist junior ultrasonographers in diagnosing uterine fibroids. To protect patients’ privacy, all identifying information, such as name, sex, age, and ID, on the ultrasound images was anonymized and omitted when the data were first acquired. This retrospective study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (Shunde Hospital of Southern Medical University). Additionally, all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All of the data in the study were obtained without any conflicts of interest.

A total of 3870 ultrasound images (2020 abnormal with uterine fibroids and 1850 normal) from 667 patients (mean age: 42.45 years ± 6.23 [SD]) with a pathological diagnosis of uterine fibroids and 570 women (mean age: 39.24 years ± 5.32 [SD]) without uterine lesions were included in the analysis. The DCNN was trained and developed on 3382 ultrasound images, which were randomly divided into a training dataset (80%, including 2706 images) and an internal validation dataset (20%, including 676 images). The model performance was tested on an external validation dataset containing 488 ultrasound images (268 uterine fibroids and 220 normal uteruses). The medical record system of the hospital provided us with the patients' clinical data (such as their ages, surgery statuses, pathological findings, surgical modalities, and postoperative ultrasound review findings). The information and imaging data of the patients with uterine fibroids are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The proportion of uterine fibroids to normal uterine ultrasound images in each dataset is shown in Table 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The ultrasound images and clinical information data of patients with uterine fibroids and normal uteri were collected from Shunde Hospital of Southern Medical University between 2015 and 2020. We controlled the quality of the ultrasound images based on the associated pathological findings. The inclusion criteria for the abnormal patient group were as follows: (1) The preoperative ultrasound suggested the presence of a uterine mass; (2) no other combined uterine masses were present; (3) the ultrasound images were in black and white; and (4) the patients were diagnosed with uterine fibroids by two senior ultrasonographers (more than 10 years of clinical experience; 10 years of seniority or more). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the patient lacked ultrasound data from our institution; and (2) images showing mass locations that did not match the clinical data. Finally, a total of 3870 ultrasound images (2020 uterine fibroids and 1850 normal uteruses) were acquired in this study.

Image acquisition

All ultrasound images were acquired in.jpg format using a color Doppler ultrasound machine. The models included the APLI300 TUS-300, APLI400 TUS-400, APLI500 TUS-500, and LOGIQ S8. The operation routes were transabdominal or transvaginal, with the abdominal ultrasound probe set at 2–7 MHz and the vaginal ultrasound probe set at 5–7 MHz.

Ground truth labeling

We randomly grouped the 3382 ultrasound images (1752 uterine fibroids and 1630 normal uteri) according to a training dataset (80%, 2706/3382) and an internal validation dataset (20%, 676/3382) for model training and development. The ground truths (GTs) of the training and validation datasets were labeled with the Visual Geometry Group Image Annotator software. Ultrasonographers with more than 10 years of experience labeled the ultrasound images of uterine fibroids through each patient’s clinical information and ultrasound image reports. If data samples with excessive labeling biases were generated, the final results were voted on again by the three ultrasonographers to determine the GT results. The system automatically generated json files, which included the image and information such, as the size and location of the GTs. The flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1. Examples of the original ultrasound data and sample data produced after labeling (including the GTs) are provided in Fig. 2.

Examples of original ultrasound data and sample data after labeling. (A) Training sample of ultrasound image with two uterine fibroids. (B) Training sample of ultrasound image with one fibroid. (C) Labeled training sample of ultrasound image with two uterine fibroids. (D) Labeled training sample of an ultrasound image with only one fibroid. The yellow box shows the extent of fibroids marked by the ultrasonographers.

DCNN-based detection algorithm

In this study, we developed a two-stage DCNN model to detect uterine fibroids in ultrasound images. The network structure in this study consisted of two parts: (1) the YOLOv320 detection network used to detect lesion regions in the ultrasound images and (2) another ResNet5021 network that was used to classify the images as normal or abnormal.

YOLOv3 is a state-of-the-art object detection network that uses features from the entire input image to predict a bounding box for each region of interest. ResNet50, a unique residual module, was used to replace the original network in YOLOv3 to learn more complex feature representations from the ultrasound images of uterine fibroids. The ResNet50 backbone was pretrained on the ImageNet22 classification task and fine-tuned on our training dataset. The original ultrasound images and the bounding boxes outlined by the radiologist, which covered the entire lesion area, were used as input data for training the YOLOv3 detection network.

All training and testing procedures were developed with Paddle (version 2.0.2), CUDA (version 10.1) and Python (version 3.7)23. Four graphics processing units (GPUs, NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1080Ti) were used, and the total training time was 10 h. The Adam24 optimizer was initialized, and each mini-batch contained 12 images. The weight decay was set as 0.0005, and the momentum was set as 0.9. A summary of the layers and output sizes of the ultrasound images produced by the DCNN during training is illustrated in Supplementary Table S1 online. The outline of the DCNN for uterine fibroid detection and some uterine fibroid detection results are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively.

Outline of the DCNN for uterine fibroid detection. Schematic representation of the DCNN network architecture for uterine fibroid detection from ultrasound images. The CBL in front of each Res module acts as a downsampling. Con-cat = tensor concatenation, which expands the dimensionality of two tensors. Add: tensor summing, no dimensionality expansion. Convs Convolutional layers, CBL Minimum component in the structure of the YOLOv3 network united by the Conv + Bn + leaky-ReLU activation function. Res-Unit Residual structure, Res-X Large component in Yolov3 consisting of a CBL and X Res-Units.

Uterine fibroid detection results. (A) Target detection results of multiple uterine fibroids in a single ultrasound image. (B) Target detection results of a single uterine fibroid in a single ultrasound image. (C) Target detection results of single uterine fibroids in patients with double ultrasound images. (D) Target detection results of multiple uterine fibroids in patients with double ultrasound images. Green boxes are the GT boxes annotated by our invited radiologists, and blue boxes are the boxes predicted by the trained model. The number marked in the upper left corner is the model detection confidence score.

Reference standard

In our local institution, the role of ultrasonographers is to examine the patient and make a diagnosis using a diagnostic ultrasound machine. In our study, four junior ultrasonographers (with less than 5 years of experience) and four senior ultrasonographers (with more than 10 years of experience) were selected to participate in determining the validation dataset, and none of them had previously been involved in the examination and interpretation of the validated ultrasound images. In the experiment, all identifying information, such as name, sex, age, and ID, on the ultrasound images were anonymized and omitted to ensure double-blindness. In addition, we scheduled the 8 ultrasonographers to perform the test at the same time in different locations to ensure their relative independence and temporal consistency. Each ultrasonographer independently interpreted the ultrasound image data contained in the external validation dataset and provided results, and four junior ultrasonographers interpreted the ultrasound image data again with the assistance of the DCNN model after interpreting the ultrasound image data individually.

Statistical analysis

To compare the performance of DL methods with that of each ultrasonographer, we calculated their sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and accuracy metrics. Sensitivity was calculated as the percentage of correctly detected uterine fibroid images, and specificity was calculated as the percentage of correctly detected normal uterine images. The number of true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN) findings yielded by the described methods were determined based on the pathological result. According to the TP rate (sensitivity) versus the FP rate (1-specificity), we calculated the areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the junior ultrasonographers, the senior ultrasonographers, the DCNN model alone, and the DCNN-assisted junior ultrasonographers. Additionally, we used the pearson's chi-square test to test the difference in the interpretations of diagnosis of uterine fibroids between junior ultrasonographers and the DCNN model, senior ultrasonographers and the DCNN model, the DCNN-assisted junior ultrasonographers and senior ultrasonographers, junior ultrasonographers with and without the DCNN’s assistance, and P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference. All statistical analyses were conducted using the software SPSS 22.0.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the hospital ethics committee (Shunde Hospital of Southern Medical University). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. We confirmed that informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Results

The DCNN’s performance on the internal validation dataset

The diagnostic performance of the DCNN model was evaluated on an internal validation dataset of ultrasound images and compared with that of currently popular detection models. The intersections over union (IoUs, see Supplementary Fig. S1 online) and confidence thresholds were set to 0.5. For the internal validation dataset, the detection results of the DCNN model produced an F1 score of 0.94. We also found that the mean average precision (mAP) of the DCNN was 92.8%, and the time taken to read a single image was 162 ms (see Supplementary Table S2 online). A complete description of the image preprocessing method and the DCNN is provided in Supplementary Methods online. The same model developed with another architecture is provided in Supplementary Fig. S2 online.

The DCNN performance compared with that of senior ultrasonographers and junior ultrasonographers

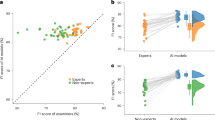

On the external validation dataset (268 uterine fibroids and 220 normal uteruses), we selected four junior ultrasonographers (with 5 years of experience or less) and four senior ultrasonographers (with more than 10 years of experience) to participate in this study. We compared the performance of the four junior ultrasonographers (Averaged), the four senior ultrasonographers (Averaged), the DCNN model and the four junior ultrasonographers (Averaged) with the DCNN-assisted in diagnosis of uterine fibroids, and the corresponding ROC graphs are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 5.

Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) show the diagnostic performance in uterine fibroids of the DCNN model, ultrasonographers with different seniority levels and junior ultrasonographers assisted by the DCNN model in the external validation dataset. The ROC curves for Junior ultrasonographers (Averaged) (blue), Senior ultrasonographers (Averaged) (orange), the DCNN model (green), and the DCNN + Junior ultrasonographers (Averaged) (red) provide corresponding AUCs of 0.87 (95% CI 0.84–0.91), 0.95 (95% CI 0.84–0.91), 0.95 (95% CI 0.92–0.97) and 0.95 (95% CI 0.93–0.97).

Comparison between the DCNN and ultrasonographers with different levels of seniority

On the external validation dataset, the DCNN model had higher accuracy (94.26% vs. 86.63%, P < 0.001), sensitivity (91.79% vs. 83.21%, P = 0.003), specificity (97.27% vs. 90.80%, P = 0.005), PPV (97.62% vs. 91.68%, P = 0.004), and NPV (90.68% vs. 81.61%, P = 0.004) than the junior ultrasonographers (Averaged). Moreover, the DCNN model had comparable accuracy (94.26% vs. 95.24%, P = 0.47), sensitivity (91.79% vs. 93.66%, P = 0.41), specificity (97.27% vs. 97.16%, P > 0.99), PPV (97.62% vs. 97.57%, P = 0.97), and NPV (90.68% vs. 92.63%, P = 0.44) to those of the senior ultrasonographers (Averaged).

Comparison of the junior ultrasonographers’ performance with and without the DCNN’s assistance

On the external validation dataset, the four junior ultrasonographers (with the assistance of the DCNN) showed substantial improvement in identifying the presence or absence of uterine fibroids. The DCNN model assisted junior ultrasonographers in diagnosing uterine fibroids with higher accuracy (94.72% vs. 86.63%, P < 0.001), sensitivity (92.82% vs. 83.21%, P = 0.001), specificity (97.05% vs. 90.80%, P = 0.009), PPV (97.45% vs. 91.68%, P = 0.007), and NPV (91.73% vs. 81.61%, P = 0.001) than they achieved alone. In terms of accuracy (94.72% vs. 95.24%, P = 0.66), sensitivity (92.82% vs. 93.66%, P = 0.73), specificity (97.05% vs. 97.16%, P = 0.79), PPV (97.45% vs. 97.57%, P = 0.77), and NPV (91.73% vs. 92.63%, P = 0.75), the DCNN-assisted junior ultrasonographers were comparable to the senior ultrasonographers (Averaged). Performance comparisons between the four junior ultrasonographers with and without the DCNN assistance are provided in Table 5.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a DCNN model for the automated detection of uterine fibroids in ultrasound images and compared this DCNN with several current and more advanced DL detection models in terms of their uterine fibroid diagnosis performance on internal and external validation datasets. With the assistance of the DCNN model, the junior ultrasonographers performed better in diagnosing uterine fibroids than they did without the model, and the resulting diagnostic performance was comparable to that of senior ultrasonographers. In addition, the DCNN model was able to simultaneously and quickly detect multiple masses of different sizes in a single image.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate a DL strategy as an aid for the diagnosis of uterine fibroids. In recent years, DL algorithms have been widely used in the field of medical image analysis25,26,27, and DCNN–based image detection methods have been commonly applied for classifying and identifying lesions28,29,30. However, no studies have been reported on the DCNNs in diagnosing uterine fibroids in ultrasound images and comparing with ultrasonographers thus far31,32,33. Even if artificial intelligence (AI) has superior performance, real world decisions should be supervised by ultrasonographers. Therefore, the most important role of an AI system is to assist junior ultrasonographers in improving the detectability of uterine fibroids.

The lack of both medical resources and senior ultrasonographers leads to poor uterine fibroid diagnostic performance and causes some patients to miss their optimal treatment opportunities2. However, the DCNN aids junior ultrasonographers in diagnosing uterine fibroids and is expected to improve this situation. The DCNN model developed in this study assisted junior ultrasonographers in diagnosing uterine fibroids in ultrasound images with higher sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy than they achieved alone. This suggests that the proposed DCNN AI model can be used to assist junior ultrasonographers in improving their diagnostic performance, thereby shortening the growth cycle of ultrasonographers.

This study has several limitations. First, this study is a single-center study, and the data may have selection bias34. In the future, multicenter studies should be conducted to improve the database required for training AI systems to improve the diagnostic capability of DCNN models. In addition, a combination of semisupervised and unsupervised network learning should be explored to reduce the data requirements of our model35,36. Second, we only trained and tested a single image of uterine fibroids instead of obtaining volume data from ultrasound images, such as CT or MRI. Selecting an image was itself influenced by the experience and skills of the performing ultrasonographers, but it does not mean that the images were purposely selected to be representative, only that there are factors that are objectively influenced. However, in real practice, ultrasonographers usually evaluate uterine fibroids using real-time ultrasound information, not an ultrasound image37. Thus, in the future, we need to study the real-time automated application of the DCNN or the DCNN with improved technology allowing the collection of ultrasound volume data, and we will gradually extend these studies to clinical work. Third, the current treatment plan for uterine fibroids is mainly based on clinical symptoms and does not rely exclusively on ultrasound diagnosis. Therefore, the DCNN model established in this study can only assist ultrasonographers in improving the diagnostic capability of uterine fibroids but not the clinical outcome of patients.

AI is unable to replace ultrasonographers by automating the diagnosis of diseases. However, as a tool for medical aid diagnosis38, it can reduce the burden of ultrasonographers in reading images. The proposed DCNN detection system can identify the presence of fibroids in ultrasound images, and it can also serve as a learning tool for junior ultrasonographers to learn to correctly differentiate uterine fibroids. In conclusion, the DCNN-assisted strategy considerably improved the uterine fibroid diagnostic performance of junior ultrasonographers. Further studies with larger sample sizes, enriched types of uterine masses, and generalized model structures are needed so that the proposed approach can be applied to other medical image analysis tasks in a quicker and more flexible manner.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Access to the data will require that investigators provide a methodologically sound protocol, demonstrate that the ethics approval has been obtained by an accredited research ethics board, apply for ethics review at the Shunde Hospital, Southern Medical University (The First People's Hospital of Shunde) and sign a data sharing agreement.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- DCNN:

-

Deep convolutional neural network

- AUC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Okolo, S. Incidence, aetiology and epidemiology of uterine fibroids. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 22, 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.04.002 (2008).

Early, H. M. et al. Pitfalls of sonographic imaging of uterine leiomyoma. Ultrasound Q. 32, 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1097/RUQ.0000000000000176 (2016).

Woźniak, A. & Woźniak, S. Ultrasonography of uterine leiomyomas. Menopause Rev. Przegląd Menopauzalny. 16, 113–117 (2017).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 42, 60–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005 (2017).

Hosny, A., Parmar, C., Quackenbush, J., Schwartz, L. H. & Aerts, H. J. W. L. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 500–510. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-018-0016-5 (2018).

Lin, L. et al. Deep learning for automated contouring of primary tumor volumes by MRI for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiology 291, 677–686. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019182012 (2019).

Kumar, A. et al. Deep feature learning for histopathological image classification of canine mammary tumors and human breast cancer. Inf. Sci. 508, 405–421 (2020).

Verma, S., & Agrawal, R. Deep neural network in medical image processing. In Handbook of Deep Learning in Biomedical Engineering. 271–292 (Academic Press, 2021).

Károly, A. I., Galambos, P., Kuti, J. & Rudas, I. J. Deep learning in robotics: Survey on model structures and training strategies. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 51, 266–279 (2020).

Hyun, D. et al. Deep learning for ultrasound image formation: CUBDL evaluation framework and open datasets. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 68, 3466–3483 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Automatic thyroid nodule recognition and diagnosis in ultrasound imaging with the YOLOv2 neural network. World J. Surg. Oncol. 17, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1558-z (2019).

Zhou, H. et al. Differential diagnosis of benign and malignant thyroid nodules using deep learning radiomics of thyroid ultrasound images. Eur. J. Radiol. 127, 108992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.108992 (2020).

Zhou, H., Wang, K. & Tian, J. Online transfer learning for differential diagnosis of benign and malignant thyroid nodules with ultrasound images. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 67, 2773–2780. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2020.2971065 (2020).

Guan, Q. et al. Deep learning based classification of ultrasound images for thyroid nodules: A large scale of pilot study. Ann. Transl. Med. 7, 137. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2019.04.34 (2019).

Fujioka, T. et al. Distinction between benign and malignant breast masses at breast ultrasound using deep learning method with convolutional neural network. Jpn. J. Radiol. 37, 466–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-019-00831-5 (2019).

Zhou, L. Q. et al. Lymph node metastasis prediction from primary breast cancer US images using deep learning. Radiology 294(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019190372 (2020).

Lin, X. et al. Ultrasound imaging for detecting metastasis to level II and III axillary lymph nodes after axillary lymph node dissection for invasive breast cancer. J. Ultrasound Med. 38, 2925–2934. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.14998 (2019).

Ciritsis, A. et al. Automatic classification of ultrasound breast lesions using a deep convolutional neural network mimicking human decision-making. Eur. Radiol. 29, 5458–5468 (2019).

Redmon, J., & Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. https:://arXiv:1804.02767 (2018).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 770–778 (2016).

Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L. J., Li, K., & Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 248–255. (IEEE, 2009).

Collobert, R., Van Der Maaten, L., & Joulin, A. Torchnet: An open-source platform for (deep) learning research. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-2016). 19–24 (2016).

Kingma, D. P., & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. https:://arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Application of deep learning neural network in pathological image classification of non-inflammatory aortic membrane degeneration. Chin. J. Pathol. 50, 620–625 (2021).

Abdel Wahab, C. et al. Diagnostic algorithm to differentiate benign atypical leiomyomas from malignant uterine sarcomas with diffusion-weighted MRI. Radiology 297, 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020191658 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Deep learning prediction of ovarian malignancy at US compared with O-RADS and expert assessment. Radiology 304, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.211367 (2022).

Lee, J. H. et al. Deep learning with ultrasonography: Automated classification of liver fibrosis using a deep convolutional neural network. Eur. Radiol. 30, 1264–1273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06407-1 (2020).

Carneiro, G. & Nascimento, J. C. Combining multiple dynamic models and deep learning architectures for tracking the left ventricle endocardium in ultrasound data. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35, 2592–2607. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2013.96 (2013).

Cho, B. J. et al. Automated classification of gastric neoplasms in endoscopic images using a convolutional neural network. Endoscopy 51, 1121–1129. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0981-6133 (2019).

Dilna, K. T., Anitha, J., Angelopoulou, A., Kapetanios, E., Chaussalet, T., & Hemanth, D. J. Classification of uterine fibroids in ultrasound images using deep learning model. In International Conference on Computational Science. 50–56 (Springer, 2022).

Suomi, V. et al. Comprehensive feature selection for classifying the treatment outcome of high-intensity ultrasound therapy in uterine fibroids. Sci. Rep. 9, 10907. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47484-y (2019).

Sundar, S. & Sumathy, S. Transfer learning approach in deep neural networks for uterine fibroid detection. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 25, 52–63 (2022).

Zhu, X., Vondrick, C., Fowlkes, C. C. & Ramanan, D. Do we need more training data?. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 119, 76–92 (2016).

Schlegl, T., Ofner, J. & Langs, G. Unsupervised pre-training across image domains improves lung tissue classification. In International MICCAI Workshop on Medical Computer Vision 82–93 (Springer, 2014).

Hofmanninger, J., & Langs, G. Mapping visual features to semantic profiles for retrieval in medical imaging. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 457–465 (2015).

Koh, J. et al. Diagnosis of thyroid nodules on ultrasonography by a deep convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 10, 15245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72270-6 (2020).

Wang, T. et al. A review on medical imaging synthesis using deep learning and its clinical applications. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 22, 11–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/acm2.13121 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Research Institute of Imaging, National Key Laboratory of Multi-Spectral Information Processing Technology, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China for their support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (No. A2020527), the Medical Research Project of Foshan Health Bureau (No. 20230068), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82172524, 81974355), the Artificial Intelligence Key Research & Development Program of Hubei Province (No. 2021BEA161).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.D. and Z.Y.: Guided the design and conduct of the project. L.L.: collected and organized the data, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the paper. T.H.: Conducted the experiments, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the paper. J.H.: Guided the project development and revised the manuscript. X.Z.: Labeled and processed the experimental images. X.C. and Q.Y.: Assisted in collecting the data. Z.W., W.W., J.Z., S.L., H.W. and Y.X. assisted in conducting the experiments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huo, T., Li, L., Chen, X. et al. Artificial intelligence-aided method to detect uterine fibroids in ultrasound images: a retrospective study. Sci Rep 13, 3714 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26771-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26771-1

This article is cited by

-

Artificial intelligence driven based diagnostics with combined surgical and non-surgical management of uterine fibroids: a narrative review

Middle East Fertility Society Journal (2025)

-

The ethics of using artificial intelligence in scientific research: new guidance needed for a new tool

AI and Ethics (2025)

-

Deep learning based uterine fibroid detection in ultrasound images

BMC Medical Imaging (2024)

-

Comparison of uterine myometrial thickness at the site of myomectomy scar after surgery using laparoscopic and laparotomy methods

Journal of Robotic Surgery (2024)

-

Role of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Image Analysis: A Review of Current Trends and Future Directions

Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering (2024)