Abstract

Chronic gastritis (CG) and osteoporosis (OP) are common and occult diseases in the elderly and the relationship of these two diseases have been increasingly exposed. We aimed to explore the clinical characteristics and shared mechanisms of CG patients combined with OP. In the cross-sectional study, all participants were selected from BEYOND study. The CG patients were included and classified into two groups, namely OP group and non-OP group. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression methods were used to evaluate the influencing factors. Furthermore, CG and OP-related genes were obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the GEO2R tool and the Venny platform. Protein–protein interaction information was obtained by inputting the intersection targets into the STRING database. The PPI network was constructed by Cytoscape v3.6.0 software again, and the key genes were screened out according to the degree value. Gene function enrichment of DEGs was performed by Webgestalt online tool. One hundred and thirty CG patients were finally included in this study. Univariate correlation analysis showed that age, gender, BMI and coffee were the potential influencing factors for the comorbidity (P < 0.05). Multivariate Logistic regression model found that smoking history, serum PTH and serum β-CTX were positively correlated with OP in CG patients, while serum P1NP and eating fruit had an negative relationship with OP in CG patients. In studies of the shared mechanisms, a total of 76 intersection genes were identified between CG and OP, including CD163, CD14, CCR1, CYBB, CXCL10, SIGLEC1, LILRB2, IGSF6, MS4A6A and CCL8 as the core genes. The biological processes closely related to the occurrence and development of CG and OP mainly involved Ferroptosis, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, Legionellosis and Chemokine signaling pathway. Our study firstly identified the possible associated factors with OP in the patients with CG, and mined the core genes and related pathways that could be used as biomarkers or potential therapeutic targets to reveal the shared mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic gastritis (CG) and osteoporosis (OP) are common and occult diseases in the elderly. According to the data of recent epidemiological studies, there has been a decrease in the proportion of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis with an increase in the contribution of other etiological factors1. The international survey in 2003–2012 found that the prevalence of CG based on endoscopic diagnosis was close to 90%2. Meanwhile, OP is a systemic skeletal disease affecting affect up to 50% of postmenopausal women and 20% of men older than 50 years, with high health and economic burden worldwide3. With the progress of OP, osteocalcin will continuously lose and the patients will experience pain and spinal deformation. Moreover, severe osteoporotic fractures may occur; some patients have decreased muscle volume and strength, and are prone to falls, leading to an increased risk of fractures and a decline in quality of life.

In recent years, the relationship between CG and OP has received more attention and has been increasingly exposed4. Many patients with CG will experience a significant reduction in bone density throughout the body. Some hormone substances secreted by secretory cells of gastric mucosa can regulate bone calcium, which are closely related to the occurrence of OP5. The occurrence of CG is mainly due to Helicobacter pylori infection, diet, lifestyle, and so on6,7,8,9. The risk factors of OP are mainly concentrated in age, diet, and lifestyle, and OP could be caused by some diseases such as gastrointestinal diseases, endocrine diseases, etc.10,11. It is a pity that there are few researches to explore the relationship of these two diseases and the related risk factors.

The shared mechanisms of CG and OP are not very clear at present, which would further hamper our investigation of the comorbidity of these two diseases. In any gastrointestinal disease, the response of low circulating leptin to weight loss may be an important factor in reducing bone mass4. It is also found that intestinal microorganisms are closely related to the regulation of intestinal permeability and bone health12. Consequently, the identified core genes may become a new research focus, and the obtained molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways contribute to the study of the relationship between CG and OP13.

In this study, we implemented the cross-sectional study in 10 communities in Beijing, China14. We aimed to analyze the clinical characteristics and associated factors for patients with CG complicated with OP. And we enriched the signaling pathways common to both by mining the shared novel genes of CG and OP, revealing their shared mechanisms. To the best of our knowledge, this might be the first study to analyze the clinical characteristics and explore the shared gene signatures between CG and OP through a cross-sectional study and using a systems biology approach.

Materials and methods

Cross-sectional studies

Study design

All participants were selected from 1540 community residents who completed past medical history inquiries and physical examinations in Chaoyang and Fengtai districts of Beijing, China from November 2017 to July 201814. In the survey, we collected the general information of 1540 community residents, current diseases, bone mineral density, diet, drug use, biological indicators and other relevant data information. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained for all material from each participant. This study had been registered on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry already. (Website: http://www.chictr.org.cn) (Registration Number: ChiCTR-SOC-17013090).

Diagnostic criteria

CG patients were determined by clinical diagnosis reports and patient self-report, regardless of the different types of CG15. The diagnostic criteria of OP patients referred to the recommendation of the World Health Organization (WHO), namely, taking into account the T value of bone mineral density: T value > − 2.5 SD was non-OP; T value ≤ − 2.5 SD was OP16 (Fig. 1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged from 45 to 80 years; (2) the subjects lived locally lasting for more than 5 years; (3) have clinical diagnosis report and patient self-report diagnosed as CG; (4) the population with complete clinical and laboratory information including BMD, bone metabolic markers.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) the participants who had missing important information; (2) having digestive tract tumors and diseases that affect bone metabolism or calcium absorption, such as diabetes and thyroid diseases, hematological diseases, leukemia, myeloma, systemic lupus erythematosus and kidney diseases; (3) Patients who received drugs or treatments that may affect the study within the first three months of the study, such as glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants.

Information acquisition

The study focuses on information collection in three aspects: population characteristics (age, gender, BMI, drinking and smoking), serum biochemical markers (β-CTX, PTH, ALP, P1NP), diet types (fruits, milk, yogurt and coffee).

Bone mineral density

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry device (Hologic, WI, USA) was used to assess the value of BMD (g/cm2). The anteroposterior L1-L4 and left proximal femur including the femoral neck and the total hip BMD were detected, and the T and Z values of each site were recorded. According to the WHO criteria, the OP and non-OP populations were identified based on bone densitometry.

Bone metabolism index detection

Fasting blood samples of the participants were collected from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. in the sitting position. The measurements were conducted through an automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay system (Roche, Cobas E601, Germany). Additionally, the blood samples were centrifuged to get serum and stored at minus 80 centigrade. As a professional third-party testing organization, Guangzhou KingMed Diagnostics Limited Liability Company was responsible for collecting and testing blood samples.

Data collection

All the data, including demographics, clinical characteristics, potential influencing factors, laboratory test and BMD results, were checked by the two independent researchers.

Studies of shared mechanisms

Access to disease genes

Microarrays related to CG and OP were acquired from the GEO database (update time: April 10, 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene). The keywords “chronic gastritis”, “osteoporosis”, and only those genes from “Homo sapiens” were used as the research targets, analyzed, and discussed in this paper. The gene expression profiling data of CG gastric epithelial tissues were obtained under accession number GSE60427, containing 15 patients with CG and 7 healthy controls, whose level was GPL17077; Gene expression profiling data of peripheral blood of OP, number GSE56116, containing 10 OP patients and 3 healthy controls, whose platform was used as GPL4133.

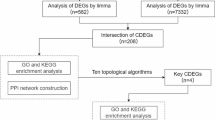

Analysis and selection of DEGs

GEO2R (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/) is an intelligent online analysis tool that can integrate and analyze two datasets under the same experimental conditions, or split any GEO data17. In this study, GEO2R tool was used to analyze the genes between CG and OP. The genes that adjusted the P < 0.05 and |log2FC|(Fold Change) > 1 were considered as DEGs. After obtaining the differentially expressed genes, online Venn analysis tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) was used to obtain DEGs intersection and specific DEGs shared by CG and OP.

Protein–protein interaction analysis

To identify the relationships among the intersection targets, we used the STRING database (https://string-db.org/). According to the comprehensive analysis of the topological parameters “closeness,” “betweenness,” and “degree”18,19. Subsequently, 10 core genes were further screened out by the cytoHubba plug-in of Cytoscape v3.6.0 software20,21,22.

GO (gene ontology) functional enrichment and KEGG signaling pathways analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) is a commonly used bioinformatics tool, which can provide relevant information according to the defined characteristics, including comprehensive information on gene function of a single genome product. GO enrichment analysis can explain gene functions from three aspects: molecular function (MF), biological process (BP) and cellular component (CC). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) is a database that systematically analyzes the metabolic pathways and functions of gene products in cells. In this study, GO and KEGG analyses were performed using WebGestalt (http://www.webgestalt.org/)23,24.

Statistical analysis

The classification variable was expressed as frequency and percentage (%). The χ2 test or Fisher exact test or Bonferroni’s method was used to compare the categorical variables between the two groups. Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze continuous variables. In addition, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the clinical characteristics of the OP and non-OP groups. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to explore the risk factors of CG complicated with OP. All the analysis was carried out with IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 software. Bidirectional alpha less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Wangjing Hospital, Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (NO. WJEC-KT-2017-020-P001) and registered on the platform of China Clinical Trial Registry (NO. ChiCTR-SOC-17013090).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

Cross-sectional studies

Participants characteristics

A total of 130 CG patients were included in this study. According to whether CG patients combined with OP, the subjects were divided into OP group (48 cases) and non-OP group (82 cases). Compared with the non-OP group, the patients of OP group were older, including 5 males (10.4%) and 43 females (89.6%) in the OP group, 26 males (31.7%) and 56 females (68.3%) in the non-OP group, and the BMI of patients in OP group was lower than that of the non-OP group. There were significant differences in age (P = 0.04), gender (P = 0.01), and BMI (P = 0.03) between OP and non-OP patients. In addition, there was no statistically significant difference in drinking and smoking history (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Comparison of biochemical markers

There was no significant difference in β-CTX, PTH, ALP, and P1NP between OP and non-OP patients (Table 2).

Comparison of diet types

In terms of diet types, coffee had a significant difference between OP and non-OP patients, while fruits, milk or yogurt had no significant difference between OP and non-OP patients (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for influencing factors

Age, gender, and BMI were taken as covariates for classification, and their correlations were taken as independent variables for Logistic regression equation analysis. Resulting that age, gender, BMI, serum PTH, serum β-CTX, serum P1NP and fruit were all related factors for CG combined with OP (Table 4, Fig. 4). Ultimately, smoking history, serum PTH and serum β-CTX were positively correlated with OP in CG patients, while serum P1NP and eating fruit had an obviously negative relationship with OP in CG patients.

Studies of comorbid mechanisms

Disease genes of OP and CG

P < 0.05 and |log2FC|(Fold Change) > 1 were as criteria for defining differential genes. Through GEO2R analysis, we found 1803 CG DEGs and 691 OP DEGs. Then, the DEGs of CG and OP were analyzed via the Venn platform, and a total of 75 DEGs were obtained. These are presented in Fig. 5A and Table 5.

PPI network construction and core gene screening

A total of 10 core genes were obtained by a 12-parameter correlation analysis of 75 intersection genes with cytoHubba. Having thus obtained the PPI data, we imported these data into Cytoscape to plot the PPI network. These are presented in Fig. 5B–D and Table 6.

GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathways enrichment analysis

The results of GO enrichment analysis consist of biological processes (BP), cell components (CC), and molecular functions (MF). To further study the biological function of key targets, an enrichment analysis of KEGG pathway was carried out. Meanwhile, the top 10 signaling pathways of key targets, including Ferroptosis, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, Pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, Legionellosis, Chemokine signaling pathway, Cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway, Acute myeloid leukemia, RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway, Phagosome, and Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (Fig. 5E–G).

Discussion

CG and OP are highly prevalent diseases around the world. A previous study showed that OP could be caused by gastrointestinal diseases, endocrine diseases, etc.10,11. With the progressive increase in the prevalence of CG and OP, it is necessary to explore the clinical characteristics and mechanism in these 2 diseases and discover the associated factors and early potential targets to prevent disease development25,26.

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection seemed to be one of the most important factors that may increase the risk of CG patients complicated with OP. A Japanese research of 230 male patients aged 50–60 years found that HP infection increased the risk of low bone mass by 1.83 times and atrophic gastritis increased the risk of low bone mass by 2.22 times. Therefore, HP infection and atrophic gastritis were considered as high-risk factors for OP27. However, the relationship between HP infection and OP is also controversial. Through a cross-sectional study of 85 female patients, Brazilian researchers found that HP-associated gastritis and autoimmune gastritis were not risk factors for abnormal bone mass28. Iranian researchers included 967 elderly people over 60 years old. The results also showed that HP infection was not significantly associated with bone mineral density change29. The prevalence of CG increases with age30. This is mainly related to the increase in Hp infection rate with age, and atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and “aging” are also related to a certain extent. In our study, CG patients with OP were older than those without OP. In addition, the high risk of elderly patients with OP may be attributed to their overall poor health, bone loss accelerated and an increase in the number of complications.

In addition, our study found that there were gender differences in patients with CG complicated with OP. Marked gender differences in the disease have been confirmed in other observational studies reporting the total incidence of autoimmune gastritis in the population is 2%, in which the incidence of elderly women is as high as 4% to 5%, and there is no race or region specificity31.

Poor lifestyle is a commonly associated factor for the occurrence of CG patients complicated with OP, including dietary preferences and drink types. A retrospective study conducted in Shanghai, China found that eating spicy food and eating fast food were risk factors for the progress of chronic atrophic gastritis7 A longitudinal study of 2682 cases in the Taiwan region of China also confirmed that the T score of bone mineral density in people with medium and high intake of coffee was higher, so it was inferred that coffee intake was negatively correlated with the risk of osteoporosis32. Moreover, smoking can lead to many health problems. Cigarettes contain many chemical components, which have great harm to the human body, especially when they are burned. One component of cigarettes is cadmium, and smoking is the main source of cadmium exposure for smokers33. Recent studies have shown that even low levels of exposure to cadmium increase the risk of osteoporosis and fractures34,35. This is consistent with our findings. We found that long-term smoking in CG patients is prone to OP, but our study found that coffee is not statistically significant, which may be related to our small sample size. However, in this study, poor eating habits are also common risk factors for OP in CG patients. Various trace nutrients in fruits are conducive to reducing the risk of chronic diseases36. Fruit intake was positively correlated with bone mineral density and negatively correlated with fracture risk11,37,38,39. In this study, the daily diet survey of the CG population found that CG patients who did not guarantee daily intake of fruits had a higher risk of OP.

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) can finely regulate bone synthesis and catabolism, and play an important role in the differentiation, maturation and apoptosis of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. PTH can up-regulate the expression of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) through parathyroid hormone receptor signaling pathway, thereby inducing bone resorption40. Studies have shown that PTH has dual effects on bone formation and bone resorption. The biological effect of PTH depends on its dose. Under the action of continuous high-dose PTH, osteoclast activity exceeds osteoblasts, resulting in bone loss greater than bone formation. Intermittent low-dose PTH promotes bone metabolism, and bone formation is greater than bone resorption, which can play a role in promoting bone formation41. Recent studies have reported that PTH can stimulate gastrin secretion and affect the absorption of Ca and P42,43,44,45, inducing OP, which was in line with our study. The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) Working Group on the Standardization of Bone Markers recommended type β-I collagen carboxy-terminal peptide (β-CTX) and type I procollagen amino-terminal peptide (P1NP) as bone turnover markers (BTMs). β-CTX is a type I collagen degradation product. When the osteoclast activity increases, a large number of type I collagen degradation will occur, resulting in an increase in the level of β-CTX. Therefore, the bone formation and bone absorption in postmenopausal women are uncoupled, and the serum β-CTX level increases46. PINP is produced in the process of type I collagen synthesis. The content of PINP in serum reflects the ability of osteoblasts to synthesize bone collagen, and can be used to monitor the vitality of osteoblasts and bone formation. Many studies have confirmed that among numerous bone metabolism indicators, PINP has high specificity and sensitivity in predicting the occurrence of osteoporosis, evaluating bone mass, and monitoring the efficacy of anti-osteoporosis47. Chen et al. found that PINP was the best predictor of BMD increase after treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis48. It was also found that the serum PINP levels in both male and female patients with osteoporosis were significantly lower than those in the normal group, and were positively correlated with BMD of the femoral neck, indicating that the osteoblast function in patients with osteoporosis decreased, the synthesis of collagen decreased, and bone formation decreased49. Our study also yielded the same results. CG people have with higher PTH and serum β-CTX, as well as lower serum P1NP have a higher risk of OP.

In studies of shared mechanisms, a total of 75 intersection genes were obtained and topologically analyzed by bioinformatic analysis of the two microarrays containing CG gastric epithelial tissues expression microarray GSE60427 and OP serum gene expression microarray GSE56116 from the GEO database, and the results indicated that CD163, CD14, CCR1, CYBB, CXCL10, SIGLEC1, LILRB2, IGSF6, MS4A6A, and CCL8 might be key targets for the treatment of CG with OP. Related studies have found that CD163 and CD14 are increased in H. pylori infection, especially in patients with peptic ulcers. CD163 and CD14 are positively associated with the severity of H. pylori infection and CD163 was also positively correlated with fracture50,51. Soluble CD14(sCD14), a proinflammatory cytokine, is primarily derived from macrophages/monocytes that can differentiate into osteoclasts, and sCD14 is an inflammatory marker associated with osteoclasts52. Gastritis and gastric tumorigenesis are associated with upregulation of CCR153. Related studies have shown that overexpression of CCR1 will increase the number of osteoclasts and osteoclast size54. CYBB is highly expressed in gastric cancer, and CYBB was identified as potential biomarkers in gastric cancer55. CG people produced higher levels of CXCL10 than healthy people56. Studies have found that CXCL10 is closely related to osteoclasts, and its downregulation can inhibit osteoclastogenesis57. SIGLEC1 provides vital pro-anabolic support to osteoblasts during both bone homeostasis and repair58. Correlative studies confirmed that LILRB2 is expressed on cultured osteoclast precursor cells derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and may inhibit osteoclast development59. IGSF6 has strong links to CG as a positional and functional candidate for susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)60. Relevant studies also found that MS4A6A was closely related to esophageal cancer and ovarian cancer and was its biomarker61, so we speculated that it also had a close correlation with the occurrence of CG and OP. CCL8 expressed and upregulated in spinal neurons after colonic inflammation, are involved in the maintenance of visceral hyperalgesia via the activation of spinal ERK62. And CCL8 is abundant in synovium and is associated with erosion of cartilage63.

Our results revealed that Ferroptosis, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, and so on were the major signaling pathways shared by CG and OP. Ni et al. found that Ferroptosis can attenuate gastric cancer cell stemness64. Ferroptosis has a close relationship with both osteoclasts and osteoblasts65. Studies have reported that disorders of iron metabolism, including iron deficiency and iron overload, can lead to osteoporosis66,67. Song et al. found that FA complementation group D2 (FANCD2) suppresses erastin-induced ferroptosis in bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), and FANCD2 reduces iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis68. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are innate immune cell receptors. Helicobacter pylori infection can stimulate innate immune response through toll-like receptor (TLR) and nuclear factor-κB activation induces the COX-2/PGE2 pathway, which leads to gastritis and gastric cancer69. And osteoblasts express TLR2, activation of TLR2 in RANKL stimulates bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) resulting in inhibition of osteoclast differentiation and formation70. Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative bacterium belonging to the epsilon-proteobacteria class, H. pylori inhabits the stomach of half of the human population worldwide, and infected individuals suffer from chronic gastritis71. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota can contribute to the development and progression of osteoporosis by regulating body immunity, hormone levels, as well as bone metabolism, and is an important cause of osteoporosis in elderly women72. Legionella species are a large collection of environmental Gram-negative bacteria that have evolved the capacity to replicate to high numbers in a range of eukaryotic cells. This trait enables some Legionella to be pathogenic to humans, particularly when the individual is immunocompromised73. However, there are few studies on Legionella on CG and OP. H pylori promoted gastric epithelial cell senescence in vitro and in vivo in a manner that depended on C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) signaling, and inhibition of CXCR2 signaling is suggested as a potential preventive therapy for targeting H pylori-induced atrophic gastritis74.

The major strength of this report lies in practical value for the management of patients with CG complicated with OP and provides some references for future researches. We are further optimizing our questionnaire and program, and want to further collect national population data, in order to provide better evidence. In studies of shared mechanisms, the cross parts of the disease genes network of CG and OP obtained in this study are the most notable genes, which is also a breakthrough point in the relationship between CG and OP. At the same time, it can also provide a more reliable path and potential targets for drugs to intervene in two interrelated diseases simultaneously. However, due to the limitation of screening conditions, only the main genes, targets and signaling pathways can be analyzed, which makes the results limited to a certain extent. Secondly, the integration of different genes depends on the development of bioinformatics technologies. The integrity and accuracy of the disease database directly determine the reliability of the integrated information. Therefore, further validations and supports of experiments in vivo and in vitro are necessary for follow-up researches.

Despite the importance of the aforementioned findings, the current study, however, has some limitations. Firstly, the diagnosis of CG is only dependent, and the diagnosis results of pathology and gastroscopy are not tracked, and we have not classified the CG population. Secondly, the scope of this study is limited to Beijing, so that the relatively small sample size might influence the interpretation of our findings. Finally, many details are still not considered fully, such as the study of comorbidities in Traditional Chinese Medicine syndrome75,76. So more associated factors of the two diseases still need to be further explored (Supplementary Information).

Conclusion

Our study reveals that age, gender, BMI, smoking history, PTH, β-CTX, P1NP and intake of fruit may be relevant risk factors for CG and OP, and uncovers the potential shared mechanism of CG and OP by identifying core genes that could be used as biomarkers or as potential therapeutic targets and related pathways through data mining.

Data availability

All data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

Livzan, M. A., Mozgovoi, S. I., Gaus, O. V., Bordin, D. S. & Kononov, A. V. Diagnostic principles for chronic gastritis associated with duodenogastric reflux. Diagnostics (Basel) 13, 186 (2023).

Jiang, J. X. et al. Downward trend in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infections and corresponding frequent upper gastrointestinal diseases profile changes in Southeastern China between 2003 and 2012. Springerplus 5, 1601 (2016).

Cummings, S. R. & Melton, L. J. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359, 1761–1767 (2002).

Bernstein, C. N. & Leslie, W. D. The pathophysiology of bone disease in gastrointestinal disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 857–864 (2003).

Persson, P., Håkanson, R., Axelson, J. & Sundler, F. Gastrin releases a blood calcium-lowering peptide from the acid-producing part of the rat stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86, 2834–2838 (1989).

Jacob, L., Hadji, P. & Kostev, K. The use of proton pump inhibitors is positively associated with osteoporosis in postmenopausal women in Germany. Climacteric 19, 478–481 (2016).

Chooi, E. Y. et al. Chronic atrophic gastritis is a progressive disease: Analysis of medical reports from Shanghai (1985–2009). Singap. Med. J. 53, 318–324 (2012).

Krantz, E., Trimpou, P. & Landin-Wilhelmsen, K. Effect of growth hormone treatment on fractures and quality of life in postmenopausal osteoporosis: A 10-year follow-up study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, 3251–3259 (2015).

Zeng, F. F. et al. Dietary patterns and the risk of hip fractures in elderly Chinese: A matched case-control study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, 2347–2355 (2013).

Benetou, V. et al. Mediterranean diet and incidence of hip fractures in a European cohort. Osteoporos. Int. 24, 1587–1598 (2013).

Xie, H. L. et al. Greater intake of fruit and vegetables is associated with a lower risk of osteoporotic hip fractures in elderly Chinese: A 1:1 matched case-control study. Osteoporos. Int. 24, 2827–2836 (2013).

Schepper, J. D. et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri prevents postantibiotic bone loss by reducing intestinal dysbiosis and preventing barrier disruption. J. Bone Miner. Res. 34, 681–698 (2019).

Lai, X. et al. Editorial: Network pharmacology and traditional medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 1194 (2020).

Sun, M. et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for community-based osteoporosis and associated fractures in Beijing: Study protocol for a cross-sectional and prospective study. Front. Med (Lausanne) 7, 544697 (2020).

Fang, J. Y. et al. Chinese consensus on chronic gastritis (2017, Shanghai). J. Dig. Dis. 19, 182–203 (2018).

Kanis, J. A., Melton, L. J. 3rd., Christiansen, C., Johnston, C. C. & Khaltaev, N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 9, 1137–1141 (1994).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Tan, A., Huang, H., Zhang, P. & Li, S. Network-based cancer precision medicine: A new emerging paradigm. Cancer Lett. 458, 39–45 (2019).

Zuo, J. et al. Integrating network pharmacology and metabolomics study on anti-rheumatic mechanisms and antagonistic effects against methotrexate-induced toxicity of Qing-Luo-Yin. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 1472 (2018).

Lei, Y. et al. A deep-learning framework for multi-level peptide-protein interaction prediction. Nat. Commun. 12, 5465 (2021).

Cline, M. S. et al. Integration of biological networks and gene expression data using Cytoscape. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2366–2382 (2007).

Clough, E. & Barrett, T. The gene expression omnibus database. Methods Mol. Biol. 1418, 93–110 (2016).

Liao, Y., Wang, J., Jaehnig, E. J., Shi, Z. & Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2019: Gene set analysis toolkit with revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W199–W205 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kim, H. W. et al. Atrophic gastritis: A related factor for osteoporosis in elderly women. PLoS One 9, e101852 (2014).

Aasarød, K. M. et al. Impaired skeletal health in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 51, 774–781 (2016).

Mizuno, S. et al. Serologically determined gastric mucosal condition is a predictive factor for osteoporosis in japanese men. Dig. Dis. Sci. 60, 2063–2069 (2015).

Kakehasi, A. M., Rodrigues, C. B., Carvalho, A. V. & Barbosa, A. J. Chronic gastritis and bone mineral density in women. Dig. Dis. Sci. 54, 819–824 (2009).

Fotouk-Kiai, M. et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection (HP) and bone mineral density (BMD) in elderly people. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 6, 62–66 (2015).

Sipponen, P. & Maaroos, H. I. Chronic gastritis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 50, 657–667 (2015).

Toh, B. H. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune gastritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 13, 459–462 (2014).

Chang, H. C. et al. Does coffee drinking have beneficial effects on bone health of Taiwanese adults? A longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 18, 1273 (2018).

Perlman, G. D., Berman, L., Leann, K. & Bing, L. Agency for toxic substances and disease registry brownfields/land-reuse site tool. J. Environ. Health 75, 30–34 (2012).

Åkesson, A. et al. Non-renal effects and the risk assessment of environmental cadmium exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 431–438 (2014).

Sommar, J. N. et al. Hip fracture risk and cadmium in erythrocytes: A nested case-control study with prospectively collected samples. Calcif. Tissue Int. 94, 183–190 (2014).

Liu, R. H. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Adv. Nutr. 4, 384S-392S (2013).

Sugiura, M. et al. Bone mineral density in post-menopausal female subjects is associated with serum antioxidant carotenoids. Osteoporos. Int. 19, 211–219 (2008).

Prynne, C. J. et al. Fruit and vegetable intakes and bone mineral status: A cross sectional study in 5 age and sex cohorts. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83, 1420–1428 (2006).

McGartland, C. P. et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and bone mineral density: The Northern Ireland Young Hearts Project. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80, 1019–1023 (2004).

Ben-awadh, A. N. et al. Parathyroid hormone receptor signaling induces bone resorption in the adult skeleton by directly regulating the RANKL gene in osteocytes. Endocrinology 155, 2797–2809 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Comparison of parathyroid hormone (1–34) and elcatonin in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: An 18-month randomized, multicenter controlled trial in China. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 126, 457–463 (2013).

Case, R. M. Calcium and gastrointestinal secretion. Digestion 8, 269–288 (1973).

Zaniewski, M., Jordan, P. H. Jr., Yip, B., Thornby, J. I. & Mallette, L. E. Serum gastrin level is increased by chronic hypercalcemia of parathyroid or nonparathyroid origin. Arch. Intern. Med. 146, 478–482 (1986).

Malagelada, J. R., Holtermuller, K. H., Sizemore, G. W. & Go, V. L. The influence of hypercalcemia on basal and cholecystokinin-stimulated pancreatic, gallbladder, and gastric functions in man. Gastroenterology 71, 405–408 (1976).

Wilson, S. D., Singh, R. B. & Kalkhoff, R. K. Does hyperparathyroidism cause hypergastrinemia?. Surgery 80, 231–237 (1976).

Li, M. et al. Chinese bone turnover marker study: Reference ranges for C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen and procollagen I N-terminal peptide by age and gender. PLoS One 9, e103841 (2014).

Krege, J. H., Lane, N. E., Harris, J. M. & Miller, P. D. PINP as a biological response marker during teriparatide treatment for osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 25, 2159–2171 (2014).

Chen, P. et al. Early changes in biochemical markers of bone formation predict BMD response to teriparatide in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 962–970 (2005).

Zhang, M. et al. 1084cases of female TRACP, CTX-1, BALP, BGP, calcium and phosphorus metabolism index and BMD correlation. Chin. J. Osteoporos. 19, 902–906 (2013).

Liu, M. et al. The distinct impact of TAM infiltration on the prognosis of patients with cardia and non-cardia gastric cancer and its association with H. pylori infection. Front. Oncol. 11, 737061 (2021).

Jaitly, V. et al. M2 macrophages in crystal storing histiocytosis associated with plasma cell myeloma. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 49, 666–670 (2019).

Bethel, M. et al. Soluble CD14 and fracture risk. Osteoporos. Int. 27, 1755–1763 (2016).

Deutsch, A. J. et al. Chemokine receptors in gastric MALT lymphoma: Loss of CXCR4 and upregulation of CXCR7 is associated with progression to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Mod. Pathol. 26, 182–194 (2013).

Liang, Z. et al. Curcumin inhibits the migration of osteoclast precursors and osteoclastogenesis by repressing CCL3 production. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 20, 234 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Identification and validation of CYBB, CD86, and C3AR1 as the key genes related to macrophage infiltration of gastric cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 756085 (2021).

Ji, R. et al. miR-374 mediates the malignant transformation of gastric cancer-associated mesenchymal stem cells in an experimental rat model. Oncol. Rep. 38, 1473–1481 (2017).

Dong, Y. et al. Inhibition of PRMT5 suppresses osteoclast differentiation and partially protects against ovariectomy-induced bone loss through downregulation of CXCL10 and RSAD2. Cell. Signal. 34, 55–65 (2017).

Batoon, L. et al. CD169+ macrophages are critical for osteoblast maintenance and promote intramembranous and endochondral ossification during bone repair. Biomaterials 196, 51–66 (2019).

Mori, Y. et al. Inhibitory immunoglobulin-like receptors LILRB and PIR-B negatively regulate osteoclast development. J. Immunol. 181, 4742–4751 (2008).

King, K. et al. Genetic variation in the IGSF6 gene and lack of association with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 30, 187–190 (2003).

Pan, X., Chen, Y. & Gao, S. Four genes relevant to pathological grade and prognosis in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biomark. 29, 169–178 (2020).

Lu, Y., Jiang, B. C., Cao, D. L., Zhao, L. X. & Zhang, Y. L. Chemokine CCL8 and its receptor CCR5 in the spinal cord are involved in visceral pain induced by experimental colitis in mice. Brain. Res. Bull. 135, 170–178 (2017).

Raghu, H. et al. CCL2/CCR2, but not CCL5/CCR5, mediates monocyte recruitment, inflammation and cartilage destruction in osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 914–922 (2017).

Ni, H. et al. MiR-375 reduces the stemness of gastric cancer cells through triggering ferroptosis. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 12, 325 (2021).

Liu, P. et al. Ferroptosis: A new regulatory mechanism in osteoporosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2634431 (2022).

Che, J. et al. The effect of abnormal iron metabolism on osteoporosis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 195, 353–365 (2020).

Cheng, Q. et al. Postmenopausal iron overload exacerbated bone loss by promoting the degradation of type I collagen. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 1345193 (2017).

Song, X. et al. FANCD2 protects against bone marrow injury from ferroptosis. Biochem. Biophys Res. Commun. 480, 443–449 (2016).

Echizen, K., Hirose, O., Maeda, Y. & Oshima, M. Inflammation in gastric cancer: Interplay of the COX-2/prostaglandin E2 and Toll-like receptor/MyD88 pathways. Cancer Sci. 107, 391–397 (2016).

Kassem, A., Lindholm, C. & Lerner, U. H. Toll-like receptor 2 stimulation of osteoblasts mediates Staphylococcus aureus induced bone resorption and osteoclastogenesis through enhanced RANKL. PLoS One 11, e0156708 (2016).

Tejada-Arranz, A. & De-Reuse, H. Riboregulation in the major gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Front. Microbiol. 12, 712804 (2021).

Nath, A. et al. Biological activities of lactose-based prebiotics and symbiosis with probiotics on controlling osteoporosis, blood-lipid and glucose levels. Medicina 54, 98 (2018).

Newton, H. J., Hartland, E. L. & Machner, M. P. Editorial: Biology and pathogenesis of Legionella. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 328 (2018).

Cai, Q. et al. Inflammation-associated senescence promotes helicobacter pylori-induced atrophic gastritis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 857–880 (2021).

Li, S. et al. Symptom combinations associated with outcome and therapeutic effects in a cohort of cases with SARS. Am. J. Chin. Med. 34, 937–947 (2006).

Su, S. B., Lu, A., Li, S. & Jia, W. Evidence-based ZHENG: A traditional Chinese medicine syndrome. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 246538 (2012).

Acknowledgements

All the authors would extend their gratitude to the subjects who contributed to this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Clinical Research Project of State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Grant number: JDZX2015076), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (Grant number: ZZ13-YQ-039, ZZ13-024-7).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: X.W., L.Z. and A.X.; Methodology: T.H., X.W. and Y.Z.; Clinical investigation and formal analysis: T.H., K.S., M.C., B.Q., X.Q., B.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation: T.H.; Writing—review and editing: A.X., Y.Z., X.W. and L.Z.; Funding acquisition: X.W. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, T., Zhang, Y., Qi, B. et al. Clinical features and shared mechanisms of chronic gastritis and osteoporosis. Sci Rep 13, 4991 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31541-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31541-8