Abstract

Using a spatiotemporal dataset of dissolved lead (dPb) from the subtropical oceans surrounding South Africa, this study quantifies the exchange of dPb between the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. Despite the absence of a major Pb source within the South Atlantic sector and the complete phase-out of leaded petroleum in Southern Africa, the ecologically important southeast Cape Basin shows an elevated surface dPb concentration (21–30 pmol kg−1). We estimated up to 90% of the measured dPb in surface waters of the Cape Basin was delivered from the Indian Ocean via the Agulhas Current (AC). Eddy dynamics and leakage at Agulhas retroflection result in an increased Pb flux from winter to summer, while a long-term (2008–2019) temporal change in dPb in the AC-derived water of Cape Basin was contemporaneous to a change in atmospheric Pb emissions from South Africa. The South African-origin atmospheric Pb, however, contributes first to the Agulhas waters in the West Indian Ocean, which is then transported to the South Atlantic, thereby regulating the dPb inventory of the Cape Basin. This indirect mechanism of Pb transfer emphasizes the importance of regulating Pb emissions from Southern Africa to protect rich fishing grounds associated with the Benguela marine ecosystem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lead (Pb) is introduced in the atmosphere through natural or anthropogenic sources1,2,3. Since the industrial revolution, the anthropogenic flux of Pb into the atmosphere has become the dominant source4,5, enhancing Pb input to the surface ocean. Therefore, modern-day dissolved Pb (dPb) concentrations in global oceans are generally higher compared to the natural oceanic background of 2.2 pmol kg−16. In oceans, Pb is not known to play any role in biological growth and is primarily scavenged and advected as it is transported to the ocean interior7,8,9. Distribution of dPb in the water column is the result of one or a combination of the following processes such as historical Pb input in the surface waters, advection of subducted water, the vertical flux of Pb by sinking particulates, and legacy Pb signatures of mixing water masses10,11. Furthermore, natural and anthropogenic Pb entering into the ocean have distinct isotopic signatures (e.g., 206Pb/207Pb). Thus, dPb and its isotopic composition are often used to understand water mass mixing7,12, atmospheric Pb transport13, and the impact of anthropogenic activities in the oceans14.

Globally, the emissions of anthropogenic Pb to the environment have decreased since the 1980s, primarily in response to the phasing out of leaded petroleum since the 1970s15. For example, the atmospheric Pb emission from Europe, a major source of Pb in the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, and Mediterranean Sea7,16,17, dropped by an estimated 90% during the 1990s18. However, contemporary Pb emissions from some developing nations (e.g., India, China) rose owing to the increased use of other Pb-emitting raw materials19,20,21. Thus, being surrounded by developing nations and despite the phasing out of leaded petroleum8,21, measured dPb in the Northeast Indian Ocean show concentrations as high as ca. 90 pmol kg−1 (based on the collection between 2010 and 2016)8,22,23.

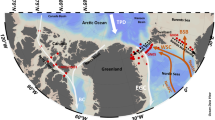

The Cape Basin, located off the west coast of South Africa (Fig. 1), is a rich and biodiverse ecosystem supporting high productivity and industrial-scale fishing grounds24. Based on the European Union limit of toxic metals including Pb, selected predatory fishes and squids from the Cape Basin (observed between 2015 and 2017) are safe for human consumption25. Nevertheless, higher Pb inputs to the region may cause intense bioaccumulation of Pb in marine species, which negatively impacts the long-term sustainability of the ecosystem. From an oceanographic perspective, the southeast Cape Basin is characterised by local circulation driven by the fast-flowing western boundary Agulhas Current (AC)26. Approximately 25% of the AC-derived water (12.2 Sv), which originates in the Pb-rich Indian ocean sector, is known to leak into the Cape Basin27. Apart from the supply along with ocean water masses, dPb in the Cape Basin could also be supplied from the erosion of Southern African continental mass and aerosols generated in Southern Africa28. Between 2007 and 2008, South Africa phased out the use of leaded petroleum29, reducing Pb input into the surrounding environment and ocean. Nevertheless, as a coal-dependent developing nation, South Africa's use of other Pb-emitting raw materials could have increased Pb emissions in recent years and their effects on ocean water, as observed in South Asian countries19,21. Therefore, in order to understand the input and variability of dPb observed in the Cape Basin, it is essential to assess the sources and internal cycling of Pb.

Source of the SST data: https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/.

Sea Surface Temperature (SST) map of the study area showing the idealised pathway of Agulhas water and associated eddies that transfer seawater from the Indian Ocean to the South Atlantic Ocean. A zoomed-out map of the study area is shown within the black square in the globe. Surface water was sampled along the transects shown by light brown lines, and the grey circles (GT9 and GT10) indicate the location of CTD stations where vertical profiles were obtained. The black vertical line is the approximate boundary between the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean.

By assessing the spatiotemporal distribution of dPb in the subtropical oceans around South Africa (Fig. 1), this research aims to identify potential sources of Pb in the Cape Basin and quantify the mixing of dPb caused by the interoceanic exchange in the upper water column. The dPb dataset was generated from samples collected from multiple oceanographic cruises between 2015 and 2019, and assessed in conjunction with previously published data28,30,31. The compiled dataset was also used to evaluate the near seasonal variation of the AC-derived water flux and associated dPb input in the Cape Basin. Based on the comparison between Pb emissions from South Africa and dPb concentrations in the Cape Basin, this study uncovers the importance of atmospheric Pb input from South Africa to the Indian Ocean-derived AC waters in influencing the dPb signature of the Atlantic waters of Cape Basin.

Result and discussion

Distribution of dPb in seawater

In the oceans surrounding South Africa (Fig. 1), dPb concentration in surface waters (< 5 m depth) ranged between 11 and 32 pmol kg−1 during August and November of 2019 (Supplementary table S1). The average dPb concentration was lower in the South Atlantic sector (average ± 1σ: 22 ± 5.8 pmol kg−1, n = 26) compared to the Indian Ocean sector (27 ± 2.8 pmol kg−1, n = 17). Within the South Atlantic sector, the elevated dPb concentrations were observed between 34 and 36.5°S, a sector within the southeast Cape Basin. Despite such spatial differences in dPb, in all post-2015 samples collected in this study, the measured dPb (Supplementary Table S1 and S2) in the southeast Cape Basin was approximately two to three times lower compared to previously published values (Sampling: 200831). That is, the concentrations of dPb at a depth of 25 m at GT10 (Lat., Long.: − 36.3, 13.3; Fig. 1), a station where dPb was also monitored in the previous voyages30,31 (see “Methods”), declined from 49 to 21 pmol kg−1 between 2008 and 2019. Despite this decadal decrease, measured dPb in the Cape Basin in 2019 (26 ± 2.5 pmol kg−1, n = 9) was still higher compared to the seawaters sampled further south between 36.5 and 40°S (14 ± 2.4 pmol kg−1, n = 8) in the South Atlantic sector (Fig. 1), suggesting additional inputs of dPb to the Cape Basin.

Air mass trajectory models suggest that in the South Atlantic sector, aerosols are primarily derived from the remote marine (Pb-depleted) air masses originating from the southwest Southern Ocean and Patagonia32,33, while the Pb-enriched anthropogenic aerosols sourced from Southern Africa are transported east to the South Indian Ocean34. The resulting Pb laden aerosols from South Africa are deposited within the AC, flowing along the east coast of South Africa. Therefore, dPb and its variability in the Cape Basin, although supporting a nearby source, may be driven primarily by AC-driven oceanic processes (section "Contribution of Agulhas Current derived Pb to the South Atlantic"), which indirectly also transfer the aerosol contribution (section "Aerosol mediated Pb in the Cape Basin").

Based on Pb isotope data, a study identified three sources of dPb in the surface water of the Cape Basin: (1) the South Atlantic surface waters where Pb-bearing aerosols from South America are deposited, (2) South African shelf sediment in the form of particulate Pb, and (3) AC-derived Indian Ocean waters28. When measured in 2015 (Supplementary Fig. S1a), there was a linear correlation between total and dissolved Pb (r2 = 0.97, p < 0.05, n = 5), suggesting suspended particulates as a potential source of dPb. However, the estimated particulate Pb fraction (%), varied from 1 to 10% of the total Pb throughout the water column (Supplementary Fig. S1b). A previous study also reported less than 2 pmol kg−1 (< 10% of the dissolved load) particulate Pb concentrations in the Cape Basin30, which suggests suspended shelf sediments to be a weak source with only a minimal dPb contribution resulting from the exchange between particulate and dissolved Pb. That is, dPb distribution in the surface water of the Cape Basin may be primarily driven by the mixing with Indian Ocean waters.

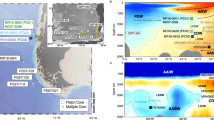

Contribution of Agulhas current derived Pb to the South Atlantic

In order to assess the mixing of water masses with variable Pb signatures, a conventional mixing diagram based on dPb and Pb isotopic composition (206Pb/207Pb vs. 1/dPb) has been used in oceanography7,35. For instance, a plot of 206Pb/207Pb and 1/dPb suggests a linear mixing of two end-members (surface water masses) in the North Atlantic7. Similarly, assuming salinity as a conservative property, the plots of salinity versus Pb concentration and Pb isotopic compositions were used to show the mixing between two intermediate water masses along the isopycnal of tropical Atlantic (GEOTRACES GA06)13. A recent study also used a similar approach to determine the mixing of dPb in the surface water masses between South China Sea and Kuroshio core36. Surface waters, as in this study region; however, are often influenced by air-sea heat exchange, evaporation, and precipitation impacting in situ properties such as temperature, salinity, and density. Therefore, to overcome the non-conservative tendencies of in situ water-mass properties, we calculated spiciness (τ), a thermophysical property of seawater that determines potential density as a function of absolute salinity (SA), conservative temperature (Tc), and pressure37 (see “Methods”). As potential density is a ‘potential property’, spiciness also possesses this potential property and is independent of the adiabatic and isohaline processes, supporting its use as an operational conservative tracer37,38,39. Based on spiciness (τ) values computed from the cruise transects, three different water masses of interest could be identified in the region (Fig. 2a). The AC waters along the east coast show the highest τ (3.99 ± 0.15) whereas the STSW waters between 36.5 and 40° S in the South Atlantic show the lowest τ (2.51 ± 0.28). In the southeast Cape Basin waters between 34 and 36.5° S, the τ values were higher (3.75 ± 0.07) compared to the rest of the South Atlantic waters, but still lower when compared to AC waters. dPb signatures also differ among these three water masses (Fig. 2b). The Cape Basin waters (26 ± 2.5 pmol kg−1) were enriched in dPb compared to the STSW (15 ± 2.4 pmol kg−1) and similar to the τ, the highest dPb concentrations were also found in the AC waters (29 ± 2.5 pmol kg−1).

Distribution of τ (a) and dPb (b) in the Subtropical oceans around South Africa in 2019. (c) The mixing diagram of dPb was made using the data presented in the a and b panels. Distribution of τ (d) and dPb concentration (e) in 2010 from published literature28,35 and the corresponding mixing diagram (f). The arrows show the idealised circulation patterns. The end members (τ and Pb) for AC (open circle) and STSW (black-filled circle) in the mixing plots were calculated from the average and standard deviation of the samples collected in different oceanic regions representing the respective water masses shown in the left panels. The bold black curve in the mixing diagram (c and f) indicates the mixing between absolute values of the two end-members. The dashed curves also indicate the mixing considering the standard deviation associated with the absolute values of the end-members (black corresponds to τ and brown corresponds 1/Pb). The dotted lines represent the contribution of AC water constructed considering both the range of τ (black) and 1/Pb (brown). The τ value for the AC in 2010 (f) was drawn based on the 2019 dataset.

In the Cape Basin, there is a lack of external source (due to the least input of atmospheric Pb) and minimum exchange between dissolved and particulate Pb that could change dPb concentration in the upper water column (section "Distribution of dPb in seawater"). Other factor that could make dPb to behave non-conservatively are the low residence time of dPb in surface seawater, riverine input to the coastal oceans, and the effect of evaporation-precipitation. Combined, all these factors have minimal quantitative impact on the dPb concentration in the study area (up to 0.02% of the measured dPb; see Supplementary Section ST1). Therefore, even though dPb is particle reactive and may behave non-conservatively in different reservoirs, it is possible to use dPb to develop the mixing diagram between two water masses (for example7,13,35,36).

In this study, the mixing diagram (τ versus 1/Pb) was constructed following the conventional mixing diagram of dPb (206Pb/207Pb versus 1/dPb) (see “Methods”). Two distinguished water masses (AC and STSW) formed the end members of the mixing diagram. Considering a variable Pb input over time and evolving dPb concentration in seawater, the proposed mixing diagram uses the dPb data of the end members and Cape Basin waters collected within the same year. The seawaters collected in 2019 shows that the surface waters (< 5 m) of Cape Basin lie on the mixing lines between the two end-member water masses (Fig. 2c). The Cape Basin waters were dominated by AC waters, accounting for 70 to 90% of the measured dPb as estimated from the mixing diagram. As a verification, a similar mixing diagram was constructed using estimated τ (based on published potential temperature: pT, practical salinity: Sp, and pressure) and previously published dPb data from the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean sectors (year of collection: 2010–201128,35; Fig. 2d–f). Due to the unavailability of pT and Sp data in the Indian Ocean sector in the observation from 201035 (Fig. 2d), we use the τ value for the year 2019 to constrain the AC end member. In the case of dPb (n = 1; Fig. 2e), the standard deviation associated with the AC in the mixing plot (Fig. 2f) was calculated from the analytical precision of dPb, which is better than 5%. The result of the second mixing diagram also indicated AC-influenced water in the Cape Basin, supplying 70 and 85% of dPb from the Indian Ocean.

For additional verification of our approach, the results were compared with the results from a conventional mixing diagram based on 201028,35 dataset of dPb and 206Pb/207Pb. Here also, the results show that the AC-influenced water in the Cape Basin was responsible for 70 to 85% of the measured dPb (Supplementary Fig. S2), consistent with the estimation using τ and dPb concentration (Fig. 2f).

The maximum depth where AC-derived water exists in the South Atlantic sector is 200 m27.Therefore, we further examined the mixing behaviour in the lower part of the surface mixed layer (SML: 25 m to mixed layer depth, MLD) of two CTD stations from the South Atlantic sector (GT9 and GT10; Fig. 1). The data-point GT9spring (SML: 25–75 m, n = 3; Supplementary Table S2) deviates from the mixing line suggesting the available water mass (STSW) had no contribution from AC waters (Fig. 2c). In contrast, GT10spring (SML: 25–45 m, n = 2) lies on the mixing line but was less dominated by the AC (45% contribution of the measured dPb) compared to the surface water (70–90% of the measured dPb). A similar fraction of AC-derived dPb was estimated at GT10 station for the water layer between the MLD and 200 m. Indeed, here as well the estimated contribution of AC-derived Pb to the Cape Basin, based on the SML (GT10) signal, was lower (45–50%) compared to that calculated from the surface water signal (70–90%). This variable response in the upper water column could simply be due to higher dPb concentration in the ACsurface than the average of ACSML samples. High dPb in AC surface waters can result from the deposition of Pb-bearing aerosols, generated in Southern Africa, that travel east34 before being deposited within the AC waters or in the source waters of AC in the Indian Ocean (see section "Aerosol mediated Pb in the Cape Basin"). The low ACSML value due to dilution on mixing with deeper waters is logical but could not be confirmed because, to the best of our knowledge, published data on vertical dPb distribution in AC (off the South African Coast) is lacking.

Seasonal variation of AC-derived Pb to the Cape Basin

On including the GT10winter(SML: 25 to 142 m, n = 5) signal on the mixing plot (Fig. 2c) we observe that the data point lies on the mixing line, but is least influenced by AC waters (ca. 30% AC-derived dPb). This indicates that there is a seasonal variation in the AC-derived dPb input in the Cape Basin. The interoceanic exchange is made possible by Agulhas leakage in the form of eddies, shedding, and filamentation that occur at the Agulhas Retroflection27 (Fig. 1). The strength of Agulhas leakage, and thus the associated chemical flux, is known to vary due to the seasonal migration of the STF and the strength of the AC itself40,41,42. Although the seasonal movements of the STF to the south in summer and to the north in winter have been reported43, we found a negligible position shift between winter (between 37.15 and 41.78° S) and spring of 2019 (between 38.90 and 41.17° S) (see “Methods”). The monthly average sea surface temperature map (MODIS-Terra SST, 11 µ daytime; https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/) shows an insignificant change in the SST at GT10 station between two sampling seasons (Supplementary Fig. S3). Thus, the observed decrease in the winter contribution of dPb to the Cape Basin is likely associated with the strength of the AC. Based on the observation from moorings across the AC, water volume transport revealed that the AC is over 25% stronger in austral summer than in winter42. Seasonal anomalies of the boundary layer transport additionally show an increasing AC-derived flow from winter to summer41,44, which would support the observed seasonal variability in the dPb flux to the Cape Basin.

To further assess the seasonality, we constructed pT versus Sp plots using available temporal data collected in the water column within the southeast Cape Basin in summer (Feb 200831 and Feb 2015), spring (Nov 201030 and Nov 2019), and winter (Aug 2019, Fig. 3). The upper water column in the Cape Basin generally comprises STSW and overlying AC-derived water during summer and spring. During summer (Feb 2008 and Feb 2015), the pT-Sp properties of the upper waters, particularly from the SML, overlapped with AC waters (Fig. 3a, c); while in other seasons, its absence is noted (Fig. 3b, d, e). More specifically, in spring (Nov 2010 and Nov 2019), the SML waters were located between the AC and STSW suggesting the moderate influence of AC water, while they fall within the error bars of STSW in winter (Aug 2019) indicating little influence of AC water. Consequently, the contribution of AC-derived water was maximum in summer, intermediate in spring, and minimum in winter, agreeing with our estimation of AC-derived Pb input to the Cape Basin.

pT and Sp properties of the water column in the Cape Basin during (a) Feb 200831, (b) Nov 201030, (c) Feb 2015, (d) Nov 2019, and (e) Aug 2019. The data points that fall close to the STSW (red circle) and AC (open diamond, error bars within the symbol) correspond to the upper water column (ca. up to 400 m depth), located inside the black circle. The pT and Sp of identified water masses in the region are given in the “Methods” section. The red oval exhibits the boundary of STSW-rich water.

The seasonality of AC-derived water and associated dPb flux, as discussed above (Figs. 2 and 3), have been confirmed using the Sea Level Anomaly (SLA). Given there is an interannual variation in the Agulhas Current leakage to the South Atlantic45, we evaluated the SLA between winter (5th august) and spring (18th November) in the year 2019, the date of sampling at GT10 (Fig. 4). The SSH anomalies show the existence of a strong anticyclonic eddy, the core of which was spatially associated with GT10 in spring. In contrast, eddy activity at GT10 during winter was weak. These observations are consistent with the increased contribution of AC-derived dPb to GT10 during spring (45%) as opposed to winter (30%).

SLA anomalies (in m) between winter (a) and spring (b), 2019. The overlaying vectors represent the geostrophic currents (in m/s). The blue dot represents the GT10 station. (Data source: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/satellite-sea-level-global?tab=form).

Decadal evolution dPb in the Cape Basin

In 2008, dPb was higher in all identified water masses compared to measurements in subsequent years (Fig. 5). Furthermore, in 2008, the average dPb in the AC-derived water mass (40 ± 6.3 pmol kg−1, n = 4) was nearly twice as high compared to the average dPb in the underlying STSW (27 ± 2.0 pmol kg−1, n = 2) with concentrations only slightly varying in deeper water masses. However, in 2010 and thereafter, the upper two water masses had comparable dPb concentrations. For instance, in 2019 (Spring), measured dPb was 20 ± 1.6 pmol kg−1 both in the STSW (n = 3) and AC (n = 4). As the Cape Basin is least influenced by AC during winter 2019 (Figs. 2 and 3), the AC-derived water was not evident in the winter of 2019.

Vertical dPb distribution over time at station GT10 in the Cape Basin. Different water masses encountered with depth are identified and their respective average dPb ± 1σ concentrations are given in brackets. Water masses were identified based on Fig. 4. Data for the years 2008 and 2010 were previously published30,31. AC water mass is not evident in 2019 due to its minimum contribution in winter (discussed in section "Seasonal variation of AC-derived Pb to the Cape Basin").

On a decadal scale, the highest variability in the southeast Cape Basin was observed in the AC-derived waters with a sharp decline in dPb (from 40 ± 6.3 to 23 ± 0.2 pmol kg−1) observed between 2008 and 2010. Given that dPb concentrations in the surface ocean are primarily contributed through wind-driven atmospheric Pb from the continents, it is reasonable to assume that the observed drop in dPb in the Cape Basin could be related to the switch from the use of leaded to unleaded petroleum in South Africa in 200829. Similarly, the marginal rise in dPb in the AC-derived water between 2015 and 2019 (Fig. 5) does not rule out the possible effect of increased use of Pb-bearing raw materials in South Africa.

Aerosol mediated Pb in the Cape Basin

Before leaded petroleum was banned in South Africa in 2008, it contributed ca. 70% to the atmospheric Pb46. The subsequent lower Pb emissions (ca. 3000 ton/year21) were reflected in the Pb content of South African aerosols sampled from the Northwest province, where Pb/Al values dropped from ca. 110 × 10–3 to 40 × 10–3 between 2006 and 201047,48,49,50,51 (Supplementary Fig. S4). That is, the decreased dPb concentration in the AC-derived water of the Cape Basin during 2008–2010 (Fig. 5) conforms to the decline in South African aerosol Pb. This would suggest that South African aerosols contribute a major fraction of Pb in the Cape Basin. However, given that the aerosols generated in Southern Africa are not transported westward to the Cape Basin (Supplementary Fig. S5), we posit that the transference of the signal is indirect. In 2019, Pb data of the aerosols collected in coastal oceans around South Africa show three times higher Pb concentrations and Pb/Al ratios on the southeast coast compared to the southwest coast52. The aerosols that accumulated airborne particles from the continent and deposited along the AC water on the east coast, display the highest levels of Pb (230 pg kg−1) and Pb/Al (8.1 × 10–3) (Supplementary Fig. S5). This, along with the dPb distribution in the Southwest Indian Ocean, which shows elevated dPb distributions close to the South African coast, confirms a considerable Pb input from South Africa to the Agulhas water along the southeast coast35.

Despite the phasing out of leaded petroleum, we observed a marginal increase between 2015 and 2019. In recent years developing nations such as South Africa and South Asian countries have increased the use of other Pb-emitting raw materials (coal, ore, unleaded petroleum)19,21. Consequently, Pb emissions have increased, but not to the same extent as when leaded petroleum was used21. While assessing the use of Pb-emitting raw materials in South Africa, we found a few instances which support increasing Pb emissions between 2015 and 2019. For example, the selected coal-fired power plants, located close to the East Coast, showed a four- to five-fold rise in particulate matter (PM) emissions because of an increased requirement for power generation53,54. Among petroleum products, the use of bitumen increased significantly as observed by the expansion of roads from 335,000 to 747,000 km between 2006 and 201755. A 30% increase in total vehicles during 2015–201756 further supports increasing Pb emissions from vehicles and roads. The impacts of these activities are corroborated by the temporal Pb/Al data of South African aerosols, which show an increase during 2015–2016 (Supplementary Fig. S4). That is, the marginal rise in AC-derived dPb in the Cape Basin between 2015 and 2019 was likely caused by the increased Pb in the South African aerosols.

The relative contribution of Pb from South African aerosols and dPb-enriched North Indian Ocean waters remains unclear due to a lack of dPb and Pb isotope data from the Southwest Indian Ocean. However, the dPb distribution in the Indian Oceans shows a difference in the dPb signature between the Southwest Indian Ocean (AC) waters, and the North and Central Indian Ocean waters (Supplementary Fig. S6). As a result, it appears that atmospheric Pb from Asia is not the primary source of Pb in the Southwest Indian Ocean. Based on the consistent temporal change in the Pb emissions from South Africa and dPb concentrations in the Cape Basin, we further posit that in the Cape Basin, a significant portion of the dPb was of atmospheric origin. However, atmospheric Pb from South Africa was first precipitated in the West Indian Ocean, then transported to the South Atlantic through the AC.

Conclusions

Dissolved Pb concentrations measured in biologically productive waters of Southeast Cape Basin are generally higher than the remaining South Atlantic sector and are a function of mixing between STSW with AC waters. Previously hypothesized exchange of dPb between SW Indian and South Atlantic Ocean via AC waters was thus quantified using a mixing diagram and dPb data measured between 2008 and 2019. From the surface to the mixed layer depth (varied from 50 to 140 m) in the Cape Basin, the water is dominated by the AC, accounting for 30 and 90% of the measured dPb with the higher-end flux contribution with the surface (< 5 m) waters. The transfer flux varied, increasing from winter to summer according to the variation in the strength of AC, which impacts the water input into the South Atlantic. By comparing the decadal scale dPb measurements (2008–2019) with Pb transport and variability in South African aerosols, it appears that South African dust is an indirect, but significant source of Pb. That is, atmospheric Pb from South Africa is first precipitated in the West Indian Ocean and is then transported to Cape Basin mediated via AC.

This study ascertains the role of AC in bringing dPb to the Cape Basin where any significant direct sources of Pb otherwise are lacking. South Africa, like other developing nations (e.g., Southeast Asian countries19), is vulnerable to increased Pb emissions in future years due to its dependence on coal energy and related economic growth. This, along with an increase in Agulhas leakage in recent decades57,58, strengthens the likelihood of future increases in the AC-derived dPb in a changing climate scenario. Thus, to protect the ecologically sensitive and commercially rich fishing grounds of Cape Basin, this study highlights the need for long-term regulation of atmospheric Pb emissions from Southern African Countries.

Methods

Sampling and analyses

In the South Atlantic sector close to the southwest coast of South Africa, surface (< 5 m depth) and deep-water samples were collected, while along the southeast coast of South Africa, only surface waters were collected. (Fig. 1). Sampling was performed on-board the R/V SA Agulhas II in January 2015 (South African National Antarctic Expedition, SANAE 54) and July–November 2019 (Southern oCean seAsonaL Experiment, SCALE) following ‘trace metal clean’ GEOTRACES sampling protocols59. Surface seawater (< 5 m) was collected using a towed-fish sampling module deployed off the side of the ship at a speed of less than 10 knots. The epoxy coated towed-fish included a PFA Teflon® nozzle to accommodate inside an acid-clean polypropylene® plastic tubing for pumping uncontaminated water directly to a Class 100 clean container lab. Water was pumped using a PTFE Teflon® diaphragm pump (Vegapumps® CE) connected to an air compressor (Lab-air® Quiet Clean Oil-free). Surface sampling was performed in winter (in the Indian Ocean sector) and spring (South Atlantic sector) (Fig. 1). The vertical profiles were sampled using clean Teflon® coated 12 l GO FLO bottles (General Oceanics) mounted on a GEOTRACES-compliant titanium CTD rosette, as described previously60,61. The vertical profiles at CTD stations GT10 and GT9 were sampled in both the winter and spring of 2019 (Fig. 1). For both surface and vertical sampling, seawater was filtered through 0.2 µm Sartobran® capsule filters and collected in 125 ml acid-cleaned low-density polyethylene (LDPE) bottles to measure the dissolved fraction of Pb. Each sample was acidified (pH ~ 1.7) by adding 250 µL 30% HCl (Merck® ultrapur). A set of unfiltered samples was separately collected in 2015, considered as the total dissolvable fraction.

Measurement of dissolved metals including dPb was performed using the established analytical setup in the TracEx laboratory, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa62. The analytical setup comprised a commercially available preconcentration unit (ESI® seaFAST S3) and a single quadrupole ICPMS (Agilent® Mass hunter 7900). Samples were analysed using either an offline setup (2015) or an online setup (2019). The measurement accuracy was determined by analysing certified (e.g., NASS7), GEOTRACES, and in-house reference seawater (Table 1). Based on the duplicate analysis of seawater samples, the analytical precision of dPb was estimated to be better than 5%. Based on the analyses of the procedural blank (1% HCl, Merck® ultrapur), the limit of detection (3 × 1σblank) was estimated to be 0.08 pmol kg-1.

The previously published dPb data30,31 of vertical profiles used in this study were sampled during the multidisciplinary MD 166 BONUSGoodHope cruise (R/V Marion Dufresne II; Feb to Mar 2008) and UK GEOTRACES GA10 cruise (RRS Discovery; Oct-Nov 2010). The published dPb data28,35 for the surface waters (< 5 m) were collected during the UK GEOTRACES GA10 cruise (RRS Discovery; Oct-Nov 2010) in the South Atlantic sector and the Malaspina 2010 Circumnavigation Expedition (R/V Hesperides; Jan-Feb 2011) in the Indian Ocean sector. For each study, trace metal clean sampling and analyses were performed. For more information, please refer to the original papers.

Estimation of spiciness

Spiciness (τ) is a function of absolute salinity (SA), conservative temperature (Tc), and pressure (p)37,38. First, the SA and CT were derived from Sp and pT, respectively.

The derivation of SA, Tc, and τ was performed in Matlab using the Gibbs SeaWater (GSW) Oceanographic Toolbox of TEOS-10 (http://www.TEOS-10.org).

Preparation of mixing diagram

The concept of mixing diagram was followed from the conventional mixing diagram of Pb using 206Pb/207Pb vs. 1/dPb7,35. The equations used to draw a mixing diagram of dPb are based on the following equations:

where f represents the fractional contribution and subscript em stands for the end-members. The isotopic mixing of Pb produces a nonlinear trend with salinity, while the mixing of dPb concentration forms a linear trend with salinity13,36. Therefore, 206Pb/207Pb vs. 1/dPb diagram produces a linear mixing trendline (Supplementary Fig. 2). In this study, we construct the mixing diagram, spiciness (τ) vs. 1/Pb, based on the following equations:

As we use 1/Pb instead of Pb, the plot of τ vs. 1/Pb produces a non-linear mixing curve between the two end-members (Fig. 2c, f).

The end-member values of dPb and τ were determined by averaging the samples collected from the regions characterizing the water mass (Fig. 2a, b, d, e). For example, the dPbAC and τAC represent the estimated values based on the samples collected along the pathway of AC on the east coast of South Africa (Table 2). The STSW variables were estimated using the samples from the south of the Cape Basin in the South Atlantic sector. Due to the unavailability of pT and Sp of the AC in 201035, we use the τAC of 2019 to draw the mixing curve in 2010 (Fig. 2f). The standard deviation associated with the dPbAC is derived based on the analytical precision of dPb (< 5%).

When we use Pb instead of using 1/Pb in the mixing diagram (τ vs. Pb), it produces linear mixing line, however, the outcome remains the same (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Identification of the frontal position

STF is a boundary that prevents subtropical surface water (STSW) from drifting further south and subantarctic surface water (SASW) from drifting further north. STF is defined by a steep rise of isohalines lines from 34.6 to 35.163,64,65. For the identification of STF during winter and spring cruises in 2019, we use the vertical distribution of salinity along the South Atlantic sectors, following approximately the GEOTRACES GIPY04 transect66.

Identification of water masses

The different water masses in the study region were identified using pT and Sp. The end member values for the water masses were selected using the published datasets67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78, compiled in Table 3. The traditional pT-Sp bidirectional plot with potential density contours was used to identify different water masses in the vertical profile (Fig. 3).

Data availability

The previously published data (pT, Sp and dissolved Pb) are available in the Geotraces Intermediate data product 201779. The SLA and geostrophic current datasets for Fig. 4 were obtained from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) ( https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/10.24381/cds.4c328c78?tab=overview). SLA is the gridded merged product of several altimeter observations: e.g., TOPEX/Poseidon, Jason—1, Jason—2, Jason—3, ERS—1, ERS—2, etc. And geostrophic velocity is a derived product from SLA observations.

References

Nriagu, J. O. Global inventory of natural and anthropogenic emissions of trace metals to the atmosphere. Nature 279, 409–411. https://doi.org/10.1038/279409a0 (1979).

Nriagu, J. O. Natural versus anthropogenic emissions of trace metals to the atmosphere. In Control and Fate of Atmospheric Trace Metals 3–13 (Springer Netherlands, 1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-2315-7_1.

Mao, J. S., Cao, J. & Graedel, T. E. Losses to the environment from the multilevel cycle of anthropogenic lead. Environ. Pollut. 157, 2670–2677 (2009).

Cloy, J. M., Farmer, J. G., Graham, M. C., MacKenzie, A. B. & Cook, G. T. Historical records of atmospheric Pb deposition in four Scottish ombrotrophic peat bogs: An isotopic comparison with other records from western Europe and Greenland. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 22, 52 (2008).

Longman, J., Ersek, V. & Veres, D. High variability between regional histories of long-term atmospheric Pb pollution. Sci. Rep. 10, 25 (2020).

Henderson, G. M. & Maier-Reimer, E. Advection and removal of 210Pb and stable Pb isotopes in the oceans: A general circulation model study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 257–272 (2002).

Noble, A. E. et al. Dynamic variability of dissolved Pb and Pb isotope composition from the US North Atlantic GEOTRACES transect. Deep Sea Res. 2 Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 116, 208–225 (2015).

Lee, J. M. et al. Impact of anthropogenic Pb and ocean circulation on the recent distribution of Pb isotopes in the Indian Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 170, 126–144 (2015).

Lee, J. M., Eltgroth, S. F., Boyle, E. A. & Adkins, J. F. The transfer of bomb radiocarbon and anthropogenic lead to the deep North Atlantic Ocean observed from a deep sea coral. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 458, 223–232 (2017).

Wu, J., Rember, R., Jin, M., Boyle, E. A. & Flegal, A. R. Isotopic evidence for the source of lead in the North Pacific abyssal water. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 4629–4638 (2010).

Boyle, E. A. et al. Lead and lead isotopes in the US GEOTRACES East Pacific zonal transect (GEOTRACES GP16). Mar. Chem. 227, 25 (2020).

Zurbrick, C. M. et al. Dissolved Pb and Pb isotopes in the North Atlantic from the GEOVIDE transect (GEOTRACES GA-01) and their decadal evolution. Biogeosci. Discuss. 2018, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2018-29 (2018).

Bridgestock, L. et al. The distribution of lead concentrations and isotope compositions in the eastern Tropical Atlantic Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 225, 36–51 (2018).

Boyle, E. A. et al. Anthropogenic lead emissions in the ocean: The evolving global experiment. Oceanography 27, 69–75 (2014).

Cullen, J. T. & McAlister, J. Biogeochemistry of lead. Its release to the environment and chemical speciation. Lead Effects Env. Health 17, 21–48 (2017).

Nicolas, E. et al. Abrupt decrease of lead concentration in the Mediterranean sea: A response to antipollution policy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 21, 2119–2122 (1994).

Wu, J. & Boyle, E. A. Lead in the western North Atlantic Ocean: Completed response to leaded gasoline phaseout. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 61, 3279–3283 (1997).

European Environment Agency. Heavy metal emissions—European Environment Agency. https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/eea32-heavy-metal-hm-emissions-1/assessment-9 (2018).

Samanta, S., Menzel Barraqueta, J. L., Das, R. & Roychoudhury, A. N. Source apportionment of the atmospheric Pb using a simulation-based inversion model: A case study from India uncovers bituminous road as the prime contributor of petroleum-derived Pb. Appl. Geochem. 136, 569 (2022).

Kumar, S. et al. Tracing dust transport from Middle-East over Delhi in March 2012 using metal and lead isotope composition. Atmos. Environ. 132, 179–187 (2016).

Lee, J. M. et al. Coral-based history of lead and lead isotopes of the surface Indian Ocean since the mid-20th century. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 398, 37–47 (2014).

Twining, B. S. et al. A nutrient limitation mosaic in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean. Deep Sea Res. 2 Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 166, 125–140 (2019).

Echegoyen, Y. et al. Recent distribution of lead in the Indian Ocean reflects the impact of regional emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 15328–15331 (2014).

Breetzke, T., Moore, L. & Celiers, L. Oceans and Coasts|155 Oceans and Coasts. https://www.dffe.gov.za/sites/default/files/reports/environmentoutlook_chapter9.pdf (2016).

Uren, R. C., Bothma, F., van der Lingen, C. D. & Bouwman, H. Differences in metal compositions and concentrations of sympatric predatory fish and squid from the South Atlantic Ocean. Afr. Zool. 55, 278–291 (2020).

Hall, C. & Lutjeharms, J. R. E. Cyclonic eddies identified in the Cape Basin of the South Atlantic Ocean. J. Mar. Syst. 85, 1–10 (2011).

Durgadoo, J. V., Rühs, S., Biastoch, A. & Böning, C. W. B. Indian Ocean sources of Agulhas leakage. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 3481–3499 (2017).

Paul, M. et al. Tracing the Agulhas leakage with lead isotopes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8515–8521 (2015).

Mathee, A. Towards the prevention of lead exposure in South Africa: Contemporary and emerging challenges. Neurotoxicology 45, 220–223 (2014).

Schlosser, C., Karstensen, J. & Woodward, E. M. S. Distribution of dissolved and leachable particulate Pb in the water column along the GEOTRACES section GA10 in the South Atlantic. Deep Sea Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 148, 132–142 (2019).

Boye, M. et al. Distributions of dissolved trace metals (Cd, Cu, Mn, Pb, Ag) in the southeastern Atlantic and the Southern Ocean. Biogeosciences 9, 3231–3246 (2012).

Chance, R., Jickells, T. D. & Baker, A. R. Atmospheric trace metal concentrations, solubility and deposition fluxes in remote marine air over the south-east Atlantic. Mar. Chem. 177, 45–56 (2015).

Baker, A. R. & Jickells, T. D. Atmospheric deposition of soluble trace elements along the Atlantic Meridional Transect (AMT). Prog. Oceanogr. 158, 41–51 (2017).

Reason, C. J. C. et al. A review of South African research in atmospheric science and physical oceanography during 2000–2005. S. Afr. J. Sci. 102, 35–45 (2006).

Pinedo-González, P., West, A. J., Tovar-Sanchez, A., Duarte, C. M. & Sañudo-Wilhelmy, S. A. Concentration and isotopic composition of dissolved Pb in surface waters of the modern global ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 235, 41–54 (2018).

Chen, M. et al. Dissolved lead (Pb) concentrations and Pb isotope ratios along the East China Sea and Kuroshio transect—evidence for isopycnal transport and particle exchange. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JC019423 (2023).

Mcdougall, T. J. & Krzysik, O. A. Spiciness. J. Mar. Res. 73, 141–152 (2015).

McDougall, T. J., Barker, P. M. & Stanley, G. J. Spice variables and their use in physical oceanography. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 126, 2 (2021).

Nagura, M. & Kouketsu, S. Spiciness anomalies in the upper South Indian Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 48, 2081–2101 (2018).

Beal, L. M., Elipot, S., Houk, A. & Leber, G. M. Capturing the transport variability of a western boundary jet: Results from the Agulhas current time-series experiment (ACT). J. Phys. Oceanogr. 45, 1302–1324 (2015).

Beal, L. M. & Elipot, S. Broadening not strengthening of the Agulhas Current since the early 1990s. Nature 540, 570–573 (2016).

Hutchinson, K., Beal, L. M., Penven, P., Ansorge, I. & Hermes, J. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans seasonal phasing of agulhas current transport tied to a baroclinic adjustment of near-field winds. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 7067–7083 (2018).

Smythe-Wright, D., Chapman, P., Duncombe-Rae, C., Shannon, L. & Boswell, S. Characteristics of the South Atlantic subtropical frontal zone between 15°W and 5°E. Deep-Sea Res. I(45), 167–192 (1998).

Biastoch, A., Reason, C. J. C., Lutjeharms, J. R. E. & Boebel, O. The importance of flow in the Mozambique Channel to seasonality in the greater Agulhas Current system. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3321–3324 (1999).

Cheng, Y., Beal, L. M., Kirtman, B. P. & Putrasahan, D. American meteorological society interannual agulhas leakage variability and its regional climate imprints. J. Clim. 31, 10105–10121 (2018).

Pacyna, J. M. & Graedel, T. E. Atmospheric emissions inventories: Status and prospects. Annu. Rev. Energy Env. 20, 265–300 (1995).

Venter, A. D. et al. Atmospheric trace metals measured at a regional background site (Welgegund) in South Africa. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 4251–4263 (2017).

Segakweng, C. K. et al. Measurement report: Size-resolved chemical characterisation of aerosols in low-income urban settlements in South Africa 2. Atmos. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2021-1026 (2022).

van-Zyl-Pieter, G. et al. Assessment of atmospheric trace metals in the western Bushveld Igneous Complex, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 110, 1–11 (2014).

Kgabi, N. A. Monitoring the Levels of Toxic Metals of Atmospheric Particulate Matter in the Rustenburg District. http://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/1504/kgabi_nnenesia.pdf;sequence=1 (2006).

Kleynhans, H. E. & Pienaar, J. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Trace Elements in Aerosols in the Vaal Triangle. http://hdl.handle.net/10394/1082 (2008).

Kangueehi, K. I. Southern African Dust Characteristics and Potential Impacts on the Surrounding Oceans (Stellenbosch University, 2021).

Morosele, I. P. & Langerman, K. E. The impacts of commissioning coal-fired power stations on air quality in South Africa: Insights from ambient monitoring stations. Clean Air J. 30, 1–11 (2020).

Zerizghi, T., Guo, Q., Zhao, C. & Okoli, C. P. Sulfur, lead, and mercury characteristics in South Africa coals and emissions from the coal-fired power plants. Environ. Earth Sci. 81, 1–15 (2022).

State of road safety report. https://www.rtmc.co.za/images/rtmc/docs/traffic_reports/calendar/Jan%20-%20Dec%202017.pdf (2017).

Department of Transport vote no. 35 annual report. https://www.transport.gov.za/documents/11623/41419/Annual_Report_201617_20170928_compressed.pdf/4fb511f8-62ad-4a70-a4d0-63dd86241fb0 (2016).

Biastoch, A., Böning, C. W., Schwarzkopf, F. U. & Lutjeharms, J. R. E. Increase in Agulhas leakage due to poleward shift of Southern Hemisphere westerlies. Nature 462, 495–498 (2009).

Rouault, M., Penven, P. & Pohl, B. Warming in the Agulhas current system since the 1980’s. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, 25 (2009).

Cutter, G. et al. Sampling and Sample-handling Protocols for GEOTRACES Cruises http://hdl.handle.net/11329/409http://dx.doi.org/10.25607/OBP-2 (2017).

Cloete, R., Loock, J. C., Mtshali, T., Fietz, S. & Roychoudhury, A. N. Winter and summer distributions of Copper, Zinc and Nickel along the International GEOTRACES Section GIPY05: Insights into deep winter mixing. Chem. Geol. 511, 342–357 (2019).

Cloete, R. et al. Winter biogeochemical cycling of dissolved and particulate cadmium in the indian sector of the Southern Ocean (GEOTRACES GIpr07 Transect). Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 1014 (2021).

Samanta, S., Cloete, R., Loock, J., Rossouw, R. & Roychoudhury, A. N. Determination of trace metal (Mn, Fe, Ni, Cu, Zn Co, Cd and Pb) concentrations in seawater using single quadrupole ICP-MS: A comparison between offline and online preconcentration setups. Minerals 11, 1289 (2021).

Deacon, G. E. R. Physical and biological zonation in the Southern Ocean. Deep Sea Res Part A Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 29, 1–15 (1982).

Orsi, H., Whitworth, T. & Nowlin, W. D. On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current Pronounced meridional gradients in surface properties separate waters of the Southern Ocean from the warmer and saltier waters of the subtropical circulations. Deacon 1933, 42 (1995).

Young-Hyang, P., Gamberoni, L. & Charriaud, E. Frontal structure, water masses, and circulation in the Crozet Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 98, 12361–12385 (1993).

Ryan-Keogh, T. SCALE Spring Trace Metal Clean CTD Rosette Data (Version 1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5906681 (2022).

Tsubouchi, T., Suga, T. & Faraday, K. H. O. S. Indian Ocean subtropical mode water: Its water characteristics and spatial distribution. Ocean Sci. Discuss. 6, 723–739 (2009).

Pardo, P. C., Pérez, F. F., Velo, A. & Gilcoto, M. Water masses distribution in the Southern Ocean: Improvement of an extended OMP (eOMP) analysis. Prog. Oceanogr. 103, 92–105 (2012).

Tomczak, M. et al. Interannual variations of water mass properties and volumes in the Southern Ocean. Ocean Sci. Discuss. 3, 199–219 (2006).

Souza, A. G. Q., de-Kerr, R. & de-Azevedo, J. L. L. On the influence of Subtropical Mode Water on the South Atlantic Ocean. J. Mar. Syst. 185, 13–24 (2018).

Weir, I. et al. Winter biogenic silica and diatom distributions in the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part I 166, 103421 (2020).

Azar, E., Piñango, A., Wallner-Kersanach, M. & Kerr, R. Source waters contribution to the tropical Atlantic central layer: New insights on the Indo-Atlantic exchanges. Deep Sea Res. Part I 168, 103450 (2021).

Brea, S. et al. Nutrient mineralization rates and ratios in the eastern South Atlantic. AGU J. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JC002051 (2004).

Jenkins, W. J., Smethie, W. M., Boyle, E. A. & Cutter, G. A. Water mass analysis for the US GEOTRACES (GA03) North Atlantic sections. Deep Sea Res. 2 Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 116, 6–20 (2015).

de Ferreira, M. L. C. & Kerr, R. Source water distribution and quantification of North Atlantic Deep Water and Antarctic Bottom Water in the Atlantic Ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 153, 66–83 (2017).

Guerrero-Feijóo, E., Nieto-Cid, M., Álvarez, M. & Álvarez-Salgado, X. A. Dissolved organic matter cycling in the confluence of the Atlantic and Indian oceans south of Africa. Deep Sea Res. Part I 83, 12–23 (2014).

Schneider, W. & Letters, L.B.-G. Argo profiling floats document Subantarctic Mode Water formation west of Drake Passage. Wiley Online Libr. 33, 16 (2006).

Carter, L., McCave, I. N., Williams, M. & Michael, J. Chapter 4 circulation and water masses of the southern ocean: A review. Dev. Earth Environ. Sci. 8, 85–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1571-9197(08)00004-9 (2008).

Schlitzer, R. et al. The GEOTRACES intermediate data product 2017. Chem. Geol. 493, 210–223 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by SANAP and CPRR Research grants (UID# 110715 and 105826) to AR from National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa. SS was funded by Subcommittee B and the Deputy Vice-Rector, Research, Stellenbosch University, and the ‘Whales and Climate Change’ research program. RC acknowledges support from the NRF Innovation Ph.D. scholarship. We thank the chief scientists of the following research programs (South African National Antarctic Expedition, SANAE 54; and Southern Ocean Seasonal Expedition, SCALE), and the captain and crew of the SA Agulhas II. We acknowledge the sampling team. Discussion with Pierrick Penven helped to develop the science. We thank editor and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. brought the scientific concept, generated data, developed the science and wrote the manuscript. R.C. generated data and reviewed the manuscript. S.P.D. provided scientific input, prepared the SLA anomalies, and reviewed the manuscript. J.C.L. generated data and reviewed the manuscript, J.L.M.B., J.O.M., J.D.B., and M.V. provided scientific input and reviewed the manuscript. A.N.R. conceived the study, provided scientific input, edited the manuscript, and funded the research program.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Samanta, S., Cloete, R., Dey, S.P. et al. Exchange of Pb from Indian to Atlantic Ocean is driven by Agulhas current and atmospheric Pb input from South Africa. Sci Rep 13, 5465 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32613-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32613-5

This article is cited by

-

Western Indian subantarctic phytoplankton blooms fertilized by iron-enriched Agulhas water

Nature Geoscience (2025)