Abstract

Out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization, especially for medical setups, is a key challenge in modern machine learning which has only recently received much attention. We investigate how different convolutional pre-trained models perform on OOD test data—that is data from domains that have not been seen during training—on histopathology repositories attributed to different trial sites. Different trial site repositories, pre-trained models, and image transformations are examined as specific aspects of pre-trained models. A comparison is also performed among models trained entirely from scratch (i.e., without pre-training) and models already pre-trained. The OOD performance of pre-trained models on natural images, i.e., (1) vanilla pre-trained ImageNet, (2) semi-supervised learning (SSL), and (3) semi-weakly-supervised learning (SWSL) models pre-trained on IG-1B-Targeted are examined in this study. In addition, the performance of a histopathology model (i.e., KimiaNet) trained on the most comprehensive histopathology dataset, i.e., TCGA, has also been studied. Although the performance of SSL and SWSL pre-trained models are conducive to better OOD performance in comparison to the vanilla ImageNet pre-trained model, the histopathology pre-trained model is still the best in overall. In terms of top-1 accuracy, we demonstrate that diversifying the images in the training using reasonable image transformations is effective to avoid learning shortcuts when the distribution shift is significant. In addition, XAI techniques—which aim to achieve high-quality human-understandable explanations of AI decisions—are leveraged for further investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With artificial neural networks, model weights can be fitted to data to generate high-precision outputs, but generalization to unseen data remains challenging. These types of challenges can be addressed under different terminologies in the literature. Some works state that unsatisfactory out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization stems from learning shortcuts1,2,3 or biases4,5,6. Some other works focus on OOD generalization from a rather different perspective stating that existing domain shift between source and target domains is the reason behind a low OOD performance7,8,9.

We can summarize different nomenclatures describing generalization issues as follows:

-

Bias

Definition: Inherent or acquired prejudice or favoritism toward an entity or group of entities known as bias, or unfairness10.

Example: Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) determines whether an offender is likely to commit another crime after being sentenced. COMPAS is used by judges to decide whether to release an offender or keep him or her in prison. The software was found to be biased against African-Americans after an investigation10.

Outcome: Inducing the generalization issue on unseen data.

-

Shortcuts

Definition: A shortcut is a decision rule that performs well on independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) test data but fails on OOD test data, resulting in a mismatch between what is intended and what has been learned1.

Example: There is a tendency for cows in unexpected environments (such as beaches instead of grasslands) to be misclassified since the background can be just as significant for recognition as the cow itself11.

Outcome: Inducing the generalization issue on unseen data.

-

Domain/distribution shift

Definition: In the context of transfer learning any differences between the source and target domain data is known as domain shift.

Example: Differences in images due to sampling bias, differences in image content or view angle, or differences in image characteristics such as brightness, noise or color12.

Outcome: Inducing the generalization issue on unseen data.

In histopathology, Hägele et al13 categorized 3 different types of biases in histopathology setups as below:

-

Dataset bias

For example, only a small portion of each image is correlated with its class label. For instance, a small central region of each image represents the class label and the remaining parts are irrelevant. In this scenario, the deep network cannot generalize to test images in which subjects do not necessarily lie at the center.

-

Label bias

Biases that are by chance correlated with class labels. If an image of a particular class has a unique red spot for instance, it may end up in a deep network that does not generalize to test images lacking this defect.

-

Sampling bias

The absence of certain critical tissue textures, such as necrosis, in the training, can lead to performance degradation in deep networks when testing them on not-seen textures.

Although they have coined their own nomenclature for biases, but all their types of biases are commonly known as shortcuts in the machine learning community which can result in a deep network with a low OOD while proper in-distribution performance. In addition to categorizing different types of biases in histopathology setups, they have demonstrated the effectiveness of explainable AI techniques to visualize the biases13.

Overall, it is critical to ensure a reliable deployment of deep models in real-life environments if there is a distribution shift, evident in differences between source and target data. For example, differences in acquisition pipelines between trial sites, or over time, may introduce a domain shift in digital pathology due to subtle and perhaps visually not apparent differences among WSIs.

A deeper understanding of distribution shift and its consequences is required to harness the significant potential offered by deep learning in histopathology. Actions need to be taken to ensure that a model’s predictions can be trusted when new data is introduced. Although correctly modeling and responding to data not seen during training is indeed a difficult problem, a few methods have recently been proposed to improve OOD generalization.

Multi-domain learning regimes (domain generalization and domain adaptation) leverage specialized training methods for OOD generalization. These types of techniques are mainly categorized into (1) simulating OOD data during training14,15,16, (2) learning invariant representations17, and (3) creating adversarial data acquisition scenarios18.

Even though domain generalization is a relatively well-studied field19, some works have cast doubt on the effectiveness of existing methods20,21. For example, Wiles et al.22 focused on three types of shifts in distributions, (1) spurious correlations, (2) low-data drifts, and (3) unseen shifts. Although their results were more mixed than conclusive, they suggested that simple techniques such as data augmentation and pre-training are “often" effective. They also demonstrated that domain generalization algorithms are effective for certain datasets and distribution shifts. They showed that the best approach cannot be selected a priori, and results differ over different datasets and attributes, demonstrating the need to further improve the algorithmic robustness in real-world settings. Therefore, it would be reasonable to ask whether domain generalization has progressed over a standard Expectation Risk Minimization (ERM) algorithm22. While those results are discouraging, there are yet other works demonstrating that machine learning models can be generalized across datasets with different distributions22,23. For instance, some works advocate that pre-training on large datasets is effective for OOD generalization22,24.

This paper presents a systematic investigation of pre-trained models for OOD generalization. Extensive experiments are conducted on different types of pre-trained models (trained with either natural images or histopathology images) with leave-one-hospital-out cross-validation. It means each of the WSI repositories associated with each hospital is held out in turn, and then the pre-trained models are fine-tuned using the remaining WSI repositories for the underlying task. To enable higher OOD generalization, our study focuses not on achieving state-of-the-art results on a benchmark dataset, but rather on a better understanding of how pre-trained models ensure proper OOD generalization. The results of this research should provide new insights into bridging the in-distribution and OOD gap for future research endeavors. Our contribution is three-fold:

-

1.

In the context of OOD generalization, we show that even though pre-training on large datasets is critical (Semi-Weakly Supervised Learning (SWSL)25 and Semi-Supervised Learning (SSL)25 versus vanilla ImageNet26 pre-trained model), the nature of the pre-trained model is crucial as well (KimiaNet27 vs. SWSL25 and SSL25). A lack of one of these components may degrade OOD generalization according to our experiments.

-

2.

With fixed-policy augmentations, OOD generalization can be improved by relying less on shortcuts and focusing more on semantically interpretable features. There is, however, a risk of complicating the deep network training as well. In other words, fixed-policy augmentation can be a friend or a foe. It all depends on the OOD test data and we may not assume a fixed-policy augmentation a priori that works for all conditions.

-

3.

There are cases in which improving in-distribution performance may deteriorate OOD performance, showing that in-distribution performance may not be a reliable indicator of OOD performance necessarily.

In the following, we introduce different types of pre-trained models that have been investigated in this study.

Vanilla pre-trained models using ImageNet

The pre-training paradigm is dominant in computer vision because many vision tasks are related, and it makes sense that a model trained on one dataset would help with another. As a result, the vanilla ImageNet pre-trained models, i.e., supervised learning on ImageNet1K dataset, have been dominating model training for various computer vision tasks28,29,30,31. Although mainly successful, some reports cast a shadow over the usefulness of vanilla ImageNet pre-trained models. For instance, Shen et al.32 demonstrated that vanilla ImageNet pre-training fails when we consider a much different task such as Microsoft COCO object detection33. Furthermore, using strong regularization, Ghiasi et al.34 found that a model trained with random initialization outperforms the ImageNet pre-trained model in COCO object detection. Thus, it seems one should not rely heavily on vanilla pre-trained models.

SSL and SWSL pre-trained models

The common sense in the AI community is that a more diverse dataset for pre-training would lead to better OOD generalization. Moreover, there have been some strong pieces of evidence that pre-trained models on more diverse datasets achieve better OOD generalization in real-life distribution shifts24,35. For instance, there are some types of pre-trained models25 that have shown better performance than vanilla ImageNet pre-trained models in terms of OOD and in-distribution top-1 accuracy levels (the one with the highest probability). Among these, two promising approaches have been introduced: (1) SSL25 pre-trained models, i.e., pre-training on a subset of the unlabeled YFCC100M public image dataset36 and fine-tuned with the ImageNet1K training dataset, (2) SWSL25 pre-trained models, i.e., training on 940 million public images with 1.5 K hashtags and 1000 ImageNet1K synsets, followed by fine-tuning on ImageNet1K. Therefore, in this study, we investigate these types of pre-trained models to see how they perform in presence of distribution shift across different histopathology image repositories.

KimiaNet pre-trained model

It is worth testing a deep model that has been pre-trained for histopathology. Compared to models trained with natural images, one might expect better performance from such networks. KimiaNet27 is a pre-trained model which has borrowed the DenseNet topology37 and has been trained on the most diverse, multi-organ public image repository, namely The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset. The details of the pre-trained models in this study has been reported in Table 1.

Experimental setup and methods

In most cases, the datasets for studying OOD performance on histopathology setups come from TCGA16,38,39. Given that KimiaNet27 has already been trained on all WSIs on TCGA data, we may not define the OOD test set from that dataset. Hence, our options are further narrowed down to other datasets. CAMELYON17 is a proper option because it contains data from various hospitals. In the following section, we describe the data and models used in our study, followed by the setup of the experiments.

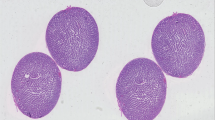

CAMELYON17 dataset

The CAMELYON17 dataset40 contains 1000 WSIs collected from five medical centers. These WSIs have not only spurious variations in stain colors41 but also variations in morphology and tumor staging across the trial sites42,43 (see Fig. 1). A total of 500 WSIs were used for training in the CAMELYON17 challenge, and the remaining 500 WSIs were used for testing. The training dataset of CAMELYON17 consists of 318 negative WSIs and 182 WSIs with metastases. Since only 50 WSIs of all the slides contained pixel-level annotations, only these 50 slides were sampled for tumor and non-tumor cells. Samples of non-tumor cells from the remaining slides might introduce some more variations; however, they are not likely to have any significant effect on the results9. Tumor areas often cover only a minor fraction of the slide area, contributing to a substantial patch-level imbalance. To address this imbalance issue, we applied a patch sampling strategy similar to that in44. Specifically, we sample the same number of tumor/normal patches on each slide with a uniform distribution of patches. Finally, for each hospital, we ended up with approximately 3000 patches, half of which are tumors and half non-tumors.

OOD hospital and data chunks

In this study, for each hospital, i.e., Hexternal, using leave-one-hospital-out, the backbone is only trained using the images of remaining hospitals, i.e., Hinternal. The Hinternal is then split into training, validation, and in-distribution test set with 70, 10, and 20% chunks, respectively. The accuracy on the Hexternal or OOD top-1 accuracy and in-distribution top-1 accuracy are calculated during the training at each epoch.

Different scenarios for the training data

Here, we propose different scenarios for fine-tuning or training the models in our experiments. To this aim, three different scenarios for the training are assessed according to Fig. 2 as follows:

A sample training batch for different scenarios. Note that the patches in scenario 1 train sets did not undergo any augmentation. As it can be seen, among identity, HED jitter, color jitter, and Gaussian blurring transformations with uniform distribution (p = 0.25), in scenario 2, one transformation is picked for each image in the batch. In scenario 3, the correct label (0: non-tumor, 1: tumor) of each image is overlaid on the image itself.

Scenario 1: The training images, i.e., Hinternal, are fed to the network without any changes.

Scenario 2: Several types of distortions in histopathology setups (see Fig. 2) are simulated and randomly (uniformly) applied to Hinternal, before inputting these images to the deep network. These transformations are as follows:

-

HED jitter45 randomly perturbs the HED color space value on an RGB histopathology image. Firstly, the hematoxylin and eosin color channels are separated by a color deconvolution method46. Following that, the hematoxylin, eosin, and Diaminobenzidine (DAB) stains are perturbed independently. In the end, the resulting stains are transformed into regular RGB color space. These perturbations are expected to make the model stain invariant.

-

Color jitter directly perturbs the image attributes including brightness, contrast, and saturation to increase image diversity so that the model is more robust to variations in color.

-

Gaussian blurring adds some blurring using a Gaussian kernel with a specific radius.

-

Identity does not make any changes to the input images.

Scenario 3: A digit (0: non-tumor and 1: tumor) corresponding to the label of images are overlaid on the top left corner of each image according to Fig. 2. We kept aside this experiment for the later sections when the shortcut learning is discussed.

Training the pre-trained models

The vanilla ImageNet pre-trained model as well as SSL25 and SWSL25 pre-trained models, all on the ResNet18 backbone47, have been used and assessed. In addition to pre-trained models on natural images, the KimiaNet pre-trained model27, which is a domain-specific (histopathology) model, has also been assessed.

For all the experiments, according to48,49, the total batch size was 32, and base learning rate was set to 0.01 for the training-from-scratch cases, and 0.001 for the pre-training cases along with step-LR schedule of 7 steps and γ = 0.1. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer, a frequently used optimizer in the literature50, was used for the training with the weight decay value of 1e − 4.

Results and discussion

During the experiments, it was observed that the in-distribution test accuracy was increasing almost smoothly during the training, while the OOD top-1 accuracy did not follow the same pattern. The underlying reason behind oscillating OOD top-1 accuracy across the epochs is that most likely during the training, a combination of both semantic and non-semantic features are learned. The non-semantic (or hospital-specific) features would counter-intuitively degrade the generalization of the OOD test data. In what follows, we compare different types of pre-trained models in terms of OOD performance.

OOD performance of the pre-trained models

From scratch versus pre-trained

The first observation was that pre-trained models outperform training from scratch on average by far. According to Table 2, the difference between training from scratch and pre-training is significant. One might conclude that using any types of reasonably pre-trained model is better than training from scratch when it comes to OOD generalization. This finding has already been reported in49.

For the training-from-scratch cases, according to Table 2, scenario 2 underperforms scenario 1 in most cases. For the pre-trained models, according to Table 2, scenario 2 outperformed scenario 1 when the hold-out dataset was hospitals 2, 3, or 5. In other words, by starting from proper initial weights (pre-trained), adding complications (augmentation/diversification) to training would result in a more generalized model. In contrast, if the deep network does not start with a proper initial weight (training from scratch), adding complexity to training would confuse it and cause it to deviate from learning meaningful and semantic features.

Vanilla versus SSL and SWSL

In Table 2, the maximum performance on each hold-out hospital has been highlighted. Neither training from scratch nor the vanilla pre-trained model has been highlighted in none of the cases. It can be observed that SSL25 and SWSL25 pre-trained models are decent alternatives for the vanilla pre-trained model. This can be justified since these two pre-trained models, i.e., SSL25 and SWSL25, have been pre-trained on a larger and more representative dataset enabling them to preserve more generic features. There have been some experiments in which training with scenario 2 has degraded OOD performance, for example, when hospital 2 was the hold-out set. Considering that this hospital has a smaller number of images than other hospitals (≈ 2000 to ≈ 3000), it may be suggested that image diversification/augmentation lowers performance as it increases the risk of complicating training of the deep network.

KimiaNet

Table 3 summarizes the result of the KimiaNet for (1) linear probing51 (which freezes the feature extractor and trains only the classification head), and for (2) fine-tuning (all the model parameters are updated). As apparent from Table 3, the results of the fine-tuning outperformed linear probing. The average results in hospitals 2, 3, and 5 are lower and more variable in comparison to hospitals 1 and 4. Training using scenario 2 has outperformed scenario 1 when the hold-out trial site was hospitals 1, 3, and 5.

Considering both Tables 2 and 3, KimiaNet outperformed all the other pre-trained models at least for three of five external validations. Hence, the domain-specific (histopathology) pre-trained model is conducive to better OOD generalization. Although linear probing, in both scenario 1 and scenario 2 cases, has outperformed training from scratch, it has underperformed all the fine-tuning cases regardless of the utilized pre-trained model.

Hospitals 3 and 5 OOD versus in-distribution performance

The variation in accuracy and performance in Tables 2 and 3 between pre-trained models and training-from-scratch for hold-out hospitals from training-from-scratch shows that deep networks perform the least among the other holdout hospitals when hospitals 2, 3 and 5 are the hold-out hospitals. Hospital 2 in comparison to the other hospitals has a lower amount of patches (≈ 2000 vs. ≈ 3000) so the variability of results and lower performance when it is used as the hold-out OOD hospital is justifiable. However, there is a need to investigate hospitals 3 and 5 since their variability can indicate that these two medical centers are likely to have a disproportionate distribution shift from others. The OOD versus in-distribution accuracies has been plotted according to Fig. 3.

Better OOD performance is preferred when it comes to real-world applications. Among different pre-trained models, we can see that when the hold-out set was hospital 5, KimiaNet outperformed other pre-trained models in terms of OOD performance. SWSL25, vanilla, and SSL25 pre-trained models secured the next places when training using scenario 2 is considered. However, in scenario 1 KimiaNet secured the first rank, and SWSL, SSL, and vanilla pre-trained models came after respectively.

Another observation was that training using scenario 2 improves OOD performance better than scenario 1 while worsen in-distribution performance for all types of pre-trained models. In other words, the transformations used in scenario 2 are effective in improving OOD performance while they caused degrading the in-distribution performance. This implies that in-distribution accuracy cannot be an indicator of OOD performance necessarily. For instance, the KimiaNet in scenario 2 has the worst in-distribution performance while the best OOD performance. It is also a noteworthy point that KimiaNet in scenario 1, when the hold-out hospital was hospital 3, has the best in-distribution and OOD performance while scenario 2 boosted the OOD performance at the cost of degrading in-distribution performance. This is the case for shortcut learning since the shortcuts, based on our general understanding, make satisfactory in-distribution performance while degrading OOD performance. Hence, we further study this case using XAI techniques to shed light on possible shortcuts.

Uncovering shortcut learning

Neural networks (or any machine learning algorithm) generally implement decision rules that define a relationship between input and output, e.g., assigning a category to each input image in classification tasks. Relying on shortcuts, the network performs well on training and in-distribution tests but not on OOD tests, indicating a mismatch between intended and learned solutions1.

Shortcut v.s. bias

In machine learning, bias is any kind of favoritism toward an entity52. Favoritism can be directed toward a specific race, or it can be directed toward particular data from a specific hospital, or even some data with specific characteristics. These types of favoritism may/may not lead to shortcut learning. It may be assumed that a bias exists when just the images from a single specific trial site are included in the training of the deep network. As a result, we would train a biased deep network that could/could not perform decently on OOD test images. The diversity of the images in that trial site determines the outcome. We may encounter a generalization issue if the images from a particular trial site are not diverse enough. Using scenario 3, we simulate a scenario in which the training images contain meaningful digits indicating their true labels. We may bias our results in favor of images with overlaid labels in this manner. While this bias results in satisfactory results when tested on images with overlaid labels, it causes the deep network to ignore the remaining contexts of the images, i.e., become biased towards the overlaid labels. In overall, all shortcuts can be termed as a bias but not all biases can be assumed as shortcuts necessarily. In other words, among all types of biases, those that end up with high in-distribution performance and low OOD performance are referred to as biases.

For all the experiments in this section, we used KimiaNet27 with the same hyperparameters that we already used in former sections, with hospital 3 as the hold-out set.

Scenario 3

As experimental shortcuts, one can overlay the true labels on the training images. When the deep network is trained using scenario 3, it may use this opportunity during training, and most likely some decision rules are learned based on this shortcut opportunity. This type of shortcut are termed as label bias in the literature13. The network will not take into account the intended and general features of the tissue context but rather the overlaid label digit. When an image without an overlaid label is tested after training, since the network has not learned meaningful decision rules, it will just output the overlaid category.

GradCAM53 was used to provide some explainability such that providing heatmaps containing the salient areas relevant to the classification. According to Figs. 4 and 5, the GradCAM heatmaps show that scenario 3 caused the deep network to focus on the overlaid label and failed to pay attention to the tissue morphology.

KimiaNet trained using Scenario 3 when tested with a tumorous OOD patch with different class labels overlaid and their corresponding GradCAM heatmaps. (left) When false label (0: non-tumor) has been overlaid on the image. According to the class prediction of the network, the network has thoroughly paid attention to the overlaid digit and misclassified the image with its misleading shortcut. (right) When the true label (1: tumor) has been overlaid. The network, by focusing on the shortcut, classified the patch with a high degree of certitude.

KimiaNet trained using Scenario 3 when tested with a healthy (non-tumor) OOD patch with different class labels overlaid and their corresponding GradCAM heatmaps. (left) When true label (0: non-tumor) has been overlaid on the image. The network, by relying on the shortcut, classified the patch with confidence. (right) When the false label (1: tumor) has been overlaid. According to the class prediction of the network, the network has thoroughly paid attention to the overlaid digit and misclassified the image with its misleading shortcut.

In other words, the extreme case of a shortcut which can be the overlaid label of the image takes precedence over any other content of the image in these cases. The deep network in these cases, similar to a digit recognizer, can only make a decision based on the digit overlaid on the image. When the overlaid class label is missed or misleading the deep network cannot provide satisfactory results.

We also tested the KimiaNet trained using scenario 3 with images without class labels overlaid. The result was the deep network randomly generated class labels and similar to flipping a coin, the accuracy was ≈ 50%.

Scenario 1 and 2

We trained KimiaNet by holding out the hospital 3 images and using both scenarios 1 and 2.

An OOD tumorous patch from hospital 3 with pathologist pixel-level annotation for the tumorous area is shown in Fig. 6i–ii. The model trained using scenario 2, correctly classified the image as tumorous and Fig. 6iii shows its salient tumorous area. While The model trained using scenario 1 misclassified the patch as healthy, the explainability heatmap for salient healthy areas is shown in Fig. 6iv. Although some tumorous areas are missed in the explainability heatmap (Fig. 6iii), the activated areas correlate well with the expert annotation whereas lymphocyte areas have not been activated. In contrast, the model trained using scenario 1 misclassified the patch as healthy; Fig. 6iv shows its heatmap for salient healthy regions. Although this heatmap is highly correlated with the healthy area (according to Fig. 6ii) but some tumorous regions erroneously have been activated as well. These regions may be attributed to shortcut opportunities that have been eliminated using the transformations of scenario 2.

The result of training using scenario 1 and scenario 2: (i) an OOD tumorous patch (from hospital 3) with different anatomical structures, Ⓣ: Tumor cells, Ⓛ: Lymphocyte, Ⓔ: Erythrocyte. (ii) Expert annotation for tumorous regions. (iii) GradCAM heatmap for the model trained using scenario 2 which correctly classified the patch, (iv) GradCAM heatmap for the model trained using scenario 1 which misclassified the patch as a healthy patch.

Figure 7i shows a patch containing healthy tissue. The trained network using scenario 1, erroneously classified this image as tumorous while the model trained by scenario 2 correctly classified it as healthy. Figure 7ii and iii show heatmaps for salient tumorous and healthy areas for scenario 1 and scenario 2, respectively. As it can be seen, the shortcut-trained model, or the model trained using scenario 1, has correlated fibrous tissues with the tumorous region. While in the model trained using scenario 2 salient healthy areas are mostly immune cells and adipocytes. Thus, it can be observed that training using scenario 2 defocused the deep network on non-semantic features (induced by spurious variations in stain colors or differences in morphology and tumor staging across hospitals/trial sites) rather than what we intend to, that is the semantics of tumorous or healthy patterns.

(i) an OOD healthy patch with different anatomical structures, Ⓘ: Immune cells, Ⓐ: Adipocyte, Ⓕ: Fibrous tissue, Ⓔ: Erythrocyte. (ii) GradCAM heatmap for the model trained using scenario 1 which misclassified the patch as a healthy patch. (iii) GradCAM heatmap for the model trained using scenario 2 which correctly classified the patch.

Different pre-training: paying attention to different image aspects

Pre-training on a related task vs. ImageNet

While pre-training on natural images, such as vanilla, SSL, and SWSL pre-trained weights, has been dominant for many computer vision tasks, there is evidence to suggest that domain-specific pre-trained weights may be more effective for certain tasks54,55. Accordingly, it is likely that a pre-trained model on a comprehensive histopathology task, e.g., cancer subtyping on TCGA, would perform better than ImageNet pre-training for a histopathology downstream task, i.e., tumorous vs. non-tumorous breast tissues on CAMELYON. This is perhaps because histopathology images have unique characteristics, such as variation in cell structures and tissue patterns, that may not be well represented in ImageNet, which is a dataset of natural images. Through pre-training on TCGA, the model would have learned more relevant features and patterns for better performance on histopathology downstream tasks.

Moreover, KimiaNet has been trained on all the common cancer types from various hospitals such as Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) and National Cancer Institute Urologic Oncology Branch (NCI), as well as others. Through Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) with the labels being cancer subtypes, the trained representations can be considered hospital-invariant to some extent. The variation among hospitals can indeed act as a form of data augmentation that can indirectly help improving the generalization of the KimiaNet. As a result, pre-training on TCGA can end up overlooking some irrelevant hospital-specific aspects of the images way better than pre-training on ImageNet. To support this hypothesis, heatmaps produced by XAI techniques were utilized in the following manner.

Heatmaps of the initial layers

The heatmaps generated by XAI techniques, especially GradCAM in this study, for the initial layers tend to highlight low-level features such as edges and corners in comparison to deeper layers which are more abstract and high-levels. These initial layers are usually left unchanged when fine-tuning a well-suited pre-trained model for the problem at hand, as they have already learned to detect “useful” features that are likely relevant to the new downstream task56. Accordingly, a crucial aspect of determining whether pre-trained weights are well-suited for downstream tasks is to assess whether fine-tuning induces significant changes to the initial layers. In this study, we investigated this issue by analyzing GradCAM heatmaps of the image shown in Fig. 8 for the first layer of each pre-trained model before and after fine-tuning (Fig. 9). Our results indicate that the initial layer responses of KimiaNet remain consistent after fine-tuning on an OOD healthy patch belonging to hospital 3, suggesting that the features captured by this pre-trained model are well-suited for the downstream task. However, for the other pre-trained models, changes in initial layer responses were observed, with the random weight model displaying the most dramatic changes. These findings suggest that careful consideration should be given to the choice of pre-trained weights for downstream tasks.

Conclusions

Although a fixed-policy diversification of images, similar to scenario 2 in this study, may lead to OOD generalization improvement, that is not necessarily the case. We showed that in some cases the data diversification, counter-intuitively, leads to poor OOD and in-distribution performance due to complicating the training of the deep networks. Hence, it is not always possible to a priori assume a policy that fits all scenarios unless the target test data and its distribution are available/known. A good example is the learnable augmentation policies57 using Cycle-Generative Adversarial Networks (Cycle-GANs)58 which is utilized for adapting the target data to source data for improving the OOD generalization. However, in this study, we assumed that there is no access to the target data during the training.

Although there are some works claiming that pre-training is not sufficiently effective, this paper showed that the use of pre-training in computer vision should not be dismissed. We have demonstrated that the newly released pre-trained vision models (SWSL, and SSL) do improve performance in many scenarios as other works have already shown that49. Additionally, we showed that KimiaNet which is a histopathology-tailored pre-trained model can outperform pre-trained models tailored toward natural images by far when the distribution shift is significant and the domain of study is histopathology.

We utilized XAI techniques to provide explanations and interpretations for certain conclusions. We presented empirical evidence that data diversification could enhance OOD performance by eliminating shortcuts, and investigated how the suitability of various pre-trained models affects the activation maps of the initial layers in deep networks.

Although some of these conclusions may be obvious, this paper presented a thorough examination of various histopathology trial site repositories, pre-trained models, and image transformations. Moreover, the paper could serve as a reference for practitioners who are not acquainted with the prevailing ideas in the field. It seems it is a common practice among the computational pathology community is to utilize ImageNet pre-trained models for their histopathology downstream tasks.

Limitations

Although our study extensively examined the performance of various pre-trained models on OOD test data in histopathology repositories, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, the study only applied ERM on different pre-trained models and did not explore other approaches such as domain adaptation and domain generalization that may offer better generalization on OOD data. Secondly, while XAI techniques were employed for interpreting the results, the explanations generated were not thoroughly analyzed. A more comprehensive investigation of these explanations could provide deeper insights into the causes of the distribution shift in histopathology domains.

Furthermore, our study only considered a limited set of pre-trained models, including vanilla ImageNet, SSL, SWSL, and KimiaNet pre-trained models. There are many other pre-trained models designed for different tasks. Therefore, the results may not be generalized to all pre-trained models.

Data availability

The dataset CAMELYON17 analysed during the current study is available in the Grand Challenge repository: https://camelyon17.grand-challenge.org/.

References

Geirhos, R. et al. Shortcut learning in deep neural networks. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 665–673 (2020).

Luo, X. et al. Rectifying the shortcut learning of background for few-shot learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 13073–13085 (2021).

Robinson, J. et al. Can contrastive learning avoid shortcut solutions?. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 4974–4986 (2021).

Tommasi, T., Patricia, N., Caputo, B. & Tuytelaars, T. A deeper look at dataset bias. In Domain Adaptation in Computer Vision Applications 37–55 (Springer, 2017).

Shimron, E., Tamir, J. I., Wang, K. & Lustig, M. Implicit data crimes: Machine learning bias arising from misuse of public data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2117203119 (2022).

Dehkharghanian, T. et al. Biased data, biased AI: Deep networks predict the acquisition site of tcga images (2021).

Stacke, K., Eilertsen, G., Unger, J. & Lundström, C. A closer look at domain shift for deep learning in histopathology. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.11575 (2019).

Luo, Y., Zheng, L., Guan, T., Yu, J. & Yang, Y. Taking a closer look at domain shift: Category-level adversaries for semantics consistent domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2507–2516 (2019).

Stacke, K., Eilertsen, G., Unger, J. & Lundström, C. Measuring domain shift for deep learning in histopathology. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 25, 325–336 (2020).

Mehrabi, N., Morstatter, F., Saxena, N., Lerman, K. & Galstyan, A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 54, 1–35 (2021).

Beery, S., Van Horn, G. & Perona, P. Recognition in terra incognita. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 456–473 (2018).

Kouw, W. M. & Loog, M. A review of domain adaptation without target labels. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 43, 766–785 (2019).

Hägele, M. et al. Resolving challenges in deep learning-based analyses of histopathological images using explanation methods. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–12 (2020).

Li, D., Yang, Y., Song, Y.-Z. & Hospedales, T. Learning to generalize: Meta-learning for domain generalization. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 32 (2018).

Dou, Q., Coelho de Castro, D., Kamnitsas, K. & Glocker, B. Domain generalization via model-agnostic learning of semantic features. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 32 (2019).

Sikaroudi, M., Rahnamayan, S. & Tizhoosh, H. R. Hospital-agnostic image representation learning in digital pathology. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.02404 (2022).

Arjovsky, M., Bottou, L., Gulrajani, I. & Lopez-Paz, D. Invariant risk minimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.02893 (2019).

Volpi, R. et al. Generalizing to unseen domains via adversarial data augmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1805.12018 (2018).

Zhou, K., Liu, Z., Qiao, Y., Xiang, T. & Loy, C. C. Domain generalization: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3195549 (2022).

Gulrajani, I. & Lopez-Paz, D. In search of lost domain generalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.01434 (2020).

Schott, L. et al. Visual representation learning does not generalize strongly within the same domain. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.08221 (2021).

Wiles, O. et al. A fine-grained analysis on distribution shift. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.11328 (2021).

Radford, A. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International Conference on Machine Learning 8748–8763 (PMLR, 2021).

Taori, R. et al. Measuring robustness to natural distribution shifts in image classification. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 18583–18599 (2020).

Yalniz, I. Z., Jégou, H., Chen, K., Paluri, M. & Mahajan, D. Billion-scale semi-supervised learning for image classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.00546 (2019).

Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 248–255 (IEEE, 2009).

Riasatian, A. et al. Fine-tuning and training of densenet for histopathology image representation using tcga diagnostic slides. Med. Image Anal. 70, 102032 (2021).

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 580–587 (2014).

Donahue, J. et al. Decaf: A deep convolutional activation feature for generic visual recognition. In International Conference on Machine Learning 647–655 (PMLR, 2014).

Long, J., Shelhamer, E. & Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 3431–3440 (2015).

Chen, L.-C., Papandreou, G., Kokkinos, I., Murphy, K. & Yuille, A. L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 40, 834–848 (2017).

Shen, Z. et al. Object detection from scratch with deep supervision. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 42, 398–412 (2019).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In European Conference on Computer Vision 740–755 (Springer, 2014).

Ghiasi, G., Lin, T.-Y. & Le, Q. V. Dropblock: A regularization method for convolutional networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 31, 100. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1810.12890 (2018).

Hendrycks, D. et al. The many faces of robustness: A critical analysis of out-of-distribution generalization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 8340–8349 (2021).

Thomee, B. et al. Yfcc100m: The new data in multimedia research. Commun. ACM 59, 64–73 (2016).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4700–4708 (2017).

Loya, H., Poduval, P., Anand, D., Kumar, N. & Sethi, A. Uncertainty estimation in cancer survival prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.08573 (2020).

Levy-Jurgenson, A., Tekpli, X., Kristensen, V. N. & Yakhini, Z. Spatial transcriptomics inferred from pathology whole-slide images links tumor heterogeneity to survival in breast and lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–11 (2020).

Bandi, P. et al. From detection of individual metastases to classification of lymph node status at the patient level: The camelyon17 challenge. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 550–560 (2018).

Tellez, D. et al. Quantifying the effects of data augmentation and stain color normalization in convolutional neural networks for computational pathology. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101544 (2019).

Bandera, E. V., Maskarinec, G., Romieu, I. & John, E. M. Racial and ethnic disparities in the impact of obesity on breast cancer risk and survival: A global perspective. Adv. Nutr. 6, 803–819 (2015).

Litjens, G. et al. 1399 H&E-stained sentinel lymph node sections of breast cancer patients: the CAMELYON dataset. GigaScience 7, giy065 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Detecting cancer metastases on gigapixel pathology images. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.02442 (2017).

Tellez, D. et al. Whole-slide mitosis detection in h&e breast histology using phh3 as a reference to train distilled stain-invariant convolutional networks. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37, 2126–2136 (2018).

Ruifrok, A. C. et al. Quantification of histochemical staining by color deconvolution. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 23, 291–299 (2001).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778 (2016).

Li, Y., Wei, C. & Ma, T. Towards explaining the regularization effect of initial large learning rate in training neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1907.04595 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. An empirical study of pre-trained vision models on out-of-distribution generalization. In NeurIPS 2021 Workshop on Distribution Shifts: Connecting Methods and Applications (2021).

Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.04747 (2016).

Kumar, A., Raghunathan, A., Jones, R., Ma, T. & Liang, P. Fine-tuning can distort pretrained features and underperform out-of-distribution. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.10054 (2022).

Hellström, T., Dignum, V. & Bensch, S. Bias in machine learning–what is it good for?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.00686 (2020).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 618–626 (2017).

Kornblith, S., Shlens, J. & Le, Q. V. Do better imagenet models transfer better?. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2661–2671 (2019).

Tajbakhsh, N. et al. Convolutional neural networks for medical image analysis: Full training or fine tuning?. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35, 1299–1312 (2016).

Huh, M., Agrawal, P. & Efros, A. A. What makes imagenet good for transfer learning?. arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.08614 (2016).

Hoffman, J. et al. Cycada: Cycle-consistent adversarial domain adaptation. In International Conference on Machine Learning 1989–1998 (Pmlr, 2018).

Zhu, J.-Y., Park, T., Isola, P. & Efros, A. A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2223–2232 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This project (ORF-RE Gigapixel Identification-Tizhoosh) is funded by an Ontario Research Fund Research Excellence grant (ORF-RE Gigapixel Identification).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. came up with the idea, carried out the experiments, and wrote the first draft of the paper. M.H. helped with designing the experimental setup. R.G. was involved in annotating the images and contributing to the paper from a medical perspective. S.R. and H.R.T. were involved in the discussions of the approach and provided critical feedback on the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.R. Tizhoosh is a co-founder of and has shares in Parapixel Diagnostics Inc. Other authors declare no Competing Financial or Non-Financial Interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sikaroudi, M., Hosseini, M., Gonzalez, R. et al. Generalization of vision pre-trained models for histopathology. Sci Rep 13, 6065 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33348-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33348-z

This article is cited by

-

Detection, localization, and staging of breast cancer lymph node metastasis in digital pathology whole slide images using selective neighborhood attention-based deep learning

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Out-of-distribution generalization for segmentation of lymph node metastasis in breast cancer

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Leveraging immuno-fluorescence data to reduce pathologist annotation requirements in lung tumor segmentation using deep learning

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Biased data, biased AI: deep networks predict the acquisition site of TCGA images

Diagnostic Pathology (2023)