Abstract

A mathematical analysis is communicated to the thermal radiation and heat absorption effects on 3D MHD Williamson nanoliquid (NFs) motion via stretching sheet. The convective heat and mass boundary conditions are taken in sheet when liquid is motion. As a novelty, the effects of thermal radiation, heat absorption and heat and mass convection are incorporated. The aim is to develop heat transfer. Williamson NFs are most important source of heat absorption, it having many significant applications in “energy generation, HT, aircraft, missiles, electronic cooling systems, gas turbines” etc. The suitable similarity transformations have been utilized for reduce basic governing P.D. E’s into coupled nonlinear system of O.D. E’s. Obtained O.D. Es are calculated by help of R–K–F (“Runge–Kutta–Fehlberg”)4th order procedure with shooting technique in MATLAB programming. We noticed that, the skin friction coefficient is more effective in Williamson liquid motion when compared with NFs motion with higher numerical values of stretching ratio parameter, Williamson liquid motion is high when compared to NFs motion for large values of magnetic field. We compared with present results into previous results for various conditions. Finally, in the present result is good invention of previous results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

New scientists have been tremendous interest for doing research in non-Newtonian liquid. Due to their broad real applications in engineering fields (“such as biological sciences, geophysics, and chemical and petroleum industries, food processing, performance of lubricants, plastic manufacture, movement of biological fluids, polymer processing, ice and magma motion”) . Property-wise non-Newtonian liquid models are “Powell-Eyring fluid, Sisko, Jeffrey fluids, Prandtl fluid, Casson fluid, and Williamson fluid models”. Out of these fluid models Williamson liquid model is attractive area for new generation. It describes the motion of shear thinning non-Newtonian liquid. Williamson fluid (“motion via stretching surface applications is copper spiralling, cod depiction, warm progressing, extrusion, and melting of high molecular weight polymers”) model is considered minimum \(\mu_{\infty }^{*}\) and maximum viscosities \(\mu_{0}^{*}\). Williamson1 developed the motion of pseudoplastic liquid and results are verified experimentally. Last few years, some of scientists2,3 develop Williamson liquid motion on 2D surface. Khan et al.4 presented Williamson nanoliquid motion via oscillating SS. The Williamson NFs via SS with variable viscosity was explored by Khan et al.5. Hashim et al.6 presents the Thermophysical features of non-Newtonian liquid motion with variable thermal conductivity. The stagnation point (SP) motion of Williamson liquid via SS was explored7,8. Some of investigators9,10 discussed the peristaltic motion of Williamson liquid. Rehman et al.11 developed numerical analysis of dual convection. The heat transfer of Williamson liquid motion via stretching cylindrical surface was explored12,13. Aziz et al.14 studied convective heat transport and volumetric entropy generation in Powell-Eyring hybrid NFs via SS. Hussain and Jamshed15 examined hybrid NFs flowing properties and thermal transport via slippy surface. Bilal et al.16 exhibited Williamson liquid motion via cylindrical surface by using Keller-Box method. Recently, some of scientists17,18,19 presented 3D liquid motion via SS. Also, some of authors20,21,22 described numerical solutions of non-Newtonian liquid motion via sheet. Some of Scientists23,24,25 explored non-Newtonian liquid motion via SS. Mishra et al.26 discussed MHD motion of power-law liquid on SS with non-uniform heat source. Jamshed et al.27 presented entropy in porous medium of Williamson NFs motion via exponentially horizontal plate. The analytical results of couple stress fluid motion via permeable sphere was created Aparna et al.28. Venkateswarlu et al.29 explored the dissipative motion of propylene-glycol and water mixture-based hybrid nanoliquid via sphere. Jamshed et al.30,31 developed Williamson NFs motion via SS.

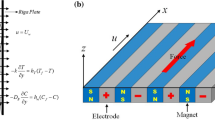

The MHD reflects dynamic activities via a stretching surface (SS). This liquid motion is electrically conducting, it established with magnetic field. The electrically conducting and heat transfer (HT) motion has many applications (“configuration orientation regarding structure of boundary layer, energy extractions in geothermal field, MHD accelerators and power generators, fluid droplets sprays and flow meters, electrostatic precipitation, polymer technology, centrifugal separation of matter from fluid, petroleum industry, magnetohydrodynamic generators, cooling systems, metallurgy, nuclear reactors, crystal growth, fluid metals and aerodynamics, accelerators, pumps, solar physics, plasma confinement, cosmology ext.”) in modern industry and engineering fields, science technology. The introduction of Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) was established by Roberts32. Jamil and Haleem33 obtained unsteady motion of fractionalized magnetohydrodynamic Jeffrey liquid via porous plate with linear slip effect. The natural convection motion of non-Newtonian liquid via different surface was focused34,35,36. The convection motion via various sheets was explored37,38,39. The MHD motion of Erying-Powell liquid via SS was discussed40,41,42. The clearance between ceramic outer ring and steel pedestal on sound radiation was discussed43. Some of authors44,45,46 presented Eyring-Powell liquid via SS. He et al.47 presented microwave imaging of 3D dielectric-magnetic penetrable objects. Tamoor et al.48 exhibited the MHD Casson liquid motion induced by stretched cylinder. MHD peristaltic transport of NFs (“copper–water”) in artery with mild stenosis for different shapes of nanoparticles is studied Devaki et al.49. Mahabaleshwar et al.50 examined the MHD Couple stress liquid due to perforated sheet via linear stretching with radiation. The MHD motion via SS was presented by51,52,53. Recently, some of investigators54,55,56 developed suction or injection for gravity modulation mixed convection in micropolar liquid via inclined sheet. The 3D MHD non-Newtonian NFs via SS was exhibited57,58,59,60. Some of the interesting and related research was studied by61,62,63. Recently64,65,66, developed MHD and convective heat transfer motion via SS. The non-Newtonian liquid motion was studied67,68,69.

The impact of thermal radiative (TR) motion has normally known as variance b/w ambient energy and thermal energy. Which is used in several fields (“biomedicine, space machinery, drilling process, cancer treatment, high temperature methods, and power generation etc. Also, several industrial processes, include nuclear reactors, power plants, gas turbines, satellites, missiles technology etc.”) of technologies. Satya Narayana et al.70 focussed the thermal radiation effect on unsteady motion via SS. Kandasamy et al.71 analysed thermal and Solutal effect on heat ad mass transfer induced due to a NFs via porous vertical plate. The mixed convection and TR on non-aligned Casson liquid via SS was discussed Mehmood et al.72 exhibited the radiative motion on 2D Casson liquid past a moving wedge. Masthanaiah et al.73 presented heat generation on cold liquid with viscous dissipation via parallel plates. The NFs motion via radiative sheet was examined74,75. Recently, some of related, interacted and motivated work presented76,77,78.

The current work numerical analysis, which is enables the young researchers to compute of convective heat and mass transfer on 3D Williamson NFs motion via SS. The effect of thermal radiation, heat absorption, MHD, convective heat and mass transfer are considered in this study. It has several applications in industrial processes, petroleum industry, nuclear reactors, power plants, molecular weight polymers, energy extractions in geothermal field, power generators, polymer technology, magnetohydrodynamic generators, cooling systems, nuclear reactors, crystal growth, biomedicine, space machinery, drilling process, cancer treatment, etc.

The main motivations of current work are:

(a) The convective heat and mass transfer boundary conditions on Williamson NFs motion, (b). The effect of heat absorption and thermal radiation is enhancement of heat transportation in Williamson NFs via SS.

(c) Particularly, numerical values of “Thermal Radiation”, “Magnetic field”, “Lewis number and Prandtl numbers” leads to minimum heat and mass transfer rate are obtained.

The present results are justified through comparison by previous study as shown Table 1 and Table 2.

(d) In future we can developed 3D non-Newtonian NFs motion via permeable stretching sheet by computational analysis.

Mathematical formulation

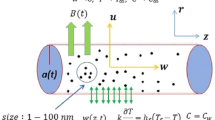

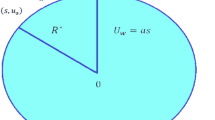

Convective heat and mass transfer on 3D magnetohydrodynamic Williamson nanoliquid motion via linear stretching surface with chemical reaction is consider. Which is assumed that stretching along \(x^{*} ,\,y^{*}\)-surface, the fluid flow direction along \(z^{*} > 0\) and flow is induced by a stretching at \(z^{*} = 0\) as displayed in Fig. 1. The non-uniform magnetic field \(M_{0}\) is taken in liquid motion direction. The stretching velocities along \(x^{*} ,\,y^{*}\)-directions as \(U_{w}^{*} = a_{1} x^{*}\) and \(V_{w}^{*} = b_{1} y^{*}\) is considered, respectively. The general equations of the Williamson liquid motion for conservative of mass, conservative of momentum is given below:

Williamson liquid model Equations are given by Ref.12,15,81,82:

The “first Rivlin-Erickson tensor” \(A_{1}\) and shear rate \(\dot{\gamma }^{*}\) is defined as below:

Consider \(\mu_{\infty }^{*} = 0\) and \(\Gamma^{*} \dot{\gamma }^{*} < 1\) thus Eq. (4) can be expressed as

Under consideration of above, the governing equations of conservative of mass, conservative of momentum, conservative of energy and concentration are formed as following Ref.12:

The boundary conditions of the present model are

The radiative heat flux \(q_{r}\) which is given by Quinn Brewster83 is given by

Neglected higher order terms we get

Differentiate above heat flux equation, we get

Substituting Eq. (14) in Eq. (4), we get below Expression

The similarity transformations as below

Using above Eq. (16), we are converting Eq. (7), (8), (9), (10) and (15) into below format

Corr. BC’s as below

The skin-friction coefficient and local Nusselt number are

While dimensionless forms of Skin friction coefficient and Nusselt number are given below:

Results and Discussions:

The transformed Eqs. (17), (18), (19) and (20) with B. C’s Eq. (21) has been solved numerically by Runge–Kutta–Fehlberg (R–K–F) 4th order algorithm along with shooting procedure. To develop the outstanding results of velocities \(\left( {f^{\prime}(\eta ),\,\,g^{\prime}(\eta )} \right)\) flows along axial and transverse directions, heat transfer \(\left( {{\text{Re}}_{x}^{ - 1/2} Nu_{x} } \right)\) rate due to related physical parameters involved in this investigation with numerical solutions are described through their plotted graphs: Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and displays tabulate values of skin friction coefficients in \(x^{*} ,\,\,y^{*}\)-directions. Throughout the study is discussed different Williamson fluid case and Newtonian case and the Prandtl number \(\left( {\Pr = 6.2} \right)\) value of water is taken in this study.

Figure 2 demonstrate that, the significant effect of \(M\)(“Magnetic field Parameter”) on \(f^{\prime}(\eta )\) (“axial direction”) in the presence of Williamson and nanoliquid motion behaviour with particular enlarge scientific values of \(M\). It is noticed, the curvature monotonically smoothly down at the point \(\eta = 0.01136\) (approximate value). Moreover, the Williamson fluid motion curve is near to the convergent area comparing nanofluid motion curvature. Finally, we decide the Williamson fluid is more significant flow more than the nanofluid flow. Physically, \(M\) is proportional to (“electrical conductivity”)\(\sigma\) and the magnetic field variation of \(M\) leads to the Lorentz force. The Lorentz force yields high resistance to transfer phenomena.

Figure 3a,b analysed that the \(N_{b}\)(“Brownian motion parameter”) on \(\theta (\eta )\), \(\phi (\eta )\) respectively. It is observed, the \(\theta (\eta )\) strictly raises with various statistical values of \(N_{b}\). Also, noticed that, the curve is monotonically increases between the region \(0 < \eta \le 0.0\,0\,3\,2\,7\,6\) and the convergent point at \(\eta = 0.0\,0\,3\,2\,7\,6\) while reverse trend shows \(\phi (\eta )\) profile for large enlarge values of \(N_{b}\). The concentration curve converges point at \(\eta = 0.0\,0\,3\,1\,7\,6\). Physically, \(N_{b}\) is interrelated to the \(D_{B}\) (“Brownian diffusion”) and \(\upsilon^{*}\) (“Kinematic viscosity”). Due to, low kinematic viscosity in motion of Williamson NFs released high temperature on SS.

Figure 4a,b predicts that the \(N_{t}\) (“Thermophoresis Parameter”) on \(\theta (\eta )\),\(\phi (\eta )\) respectively in Williamson nanofluid flow. It is detected that the both \(\theta (\eta )\), \(\phi (\eta )\) monotonically increases with \(\lambda = \alpha = \Gamma_{1} = \Gamma_{2} = Le = 0.1\), \(H = M = 0.2\), \(R_{d} = 0.5\) and \(\Pr = 6.2\). Also, recognized that the both heat and concentration curves is strictly increases between the area \(0 < \eta \le 0.0\,0\,5\,0\,8\,1\) and the exact convergent point at \(\eta = 0.0\,0\,5\,0\,8\,1\). Physically, \(N_{t}\) is proportional to thermal diffusion \(D_{T}\). The high thermal diffusivity produces more temperature and concentration of Williamson NFs motion via SS.

Figures 5a,b illustrate that the \(R_{d}\) (“Thermal Radiation parameter”) in Williamson nanofluid flow on \(\theta (\eta )\), \(\phi (\eta )\) respectively. It is observed that the both \(\theta (\eta )\), \(\phi (\eta )\) monotonically increases with \(\lambda = \alpha = \Gamma_{1} = \Gamma_{2} = Le = 0.1\), \(H = M = N_{t} = 0.2\), \(N_{b} = 0.5\) and \(\Pr = 6.2\). Also, noticed that the both heat and concentration curves is strictly increases within the region \(0 < \eta \le 0.0\,0\,5\,0\,5\,2\) and the exact convergent point at \(\eta = 0.0\,0\,5\,0\,5\,2\). Physically, \(R_{d}\) is inversely proportional to mean absorption coefficient.

Figure 6 presented that the \(Le\) (“Lewis number”) on \(\phi (\eta )\). It is clear that the concentration curve smoothly down in Williamson NFs fluid flow with various physical parameter values of \(\lambda = \alpha = \Gamma_{1} = \Gamma_{2} = 0.1\), \(H = M = N_{t} = 0.2\), \(\Pr = 6.2\) and \(R_{d} = N_{b} = 0.5\). Moreover, the curve monotonically decreases within the region \(0 < \eta \le 0.0\,0\,3\,9\,0\,5\) and convergent area at \(\eta = 0.0\,0\,3\,9\,0\,5\) approaches to zero. Physically, \(Le\) is ratio between thermal conductivity \(\alpha_{m}\) and Brownian diffusion \(D_{B}\). The high Brownian diffusion released low concentration in Williamson NFs motion via SS.

Figure 7 explained that the both \(\Pr\)(“Prandtl number”), \(H\) (“Heat source Parameter”) on \(\theta (\eta )\). It is clear that the energy layer smoothly down in Williamson NFs liquid motion for fixed enlarge values of respected physical parameters. Moreover, it is observed that the Prandtl curve converges monotonically within the region \(0 < \eta \le 0.0\,0\,1\,2\,7\,1\) at \(\theta = 8.5\) and consequently the heat absorption curvature monotonically down between regions \(0 < \eta \le 0.0\,0\,1\,9\,4\) at \(\theta = 8.5\). Physical,\(\Pr\),\(H\) are inversely proportional to the thermal conductivity, fluid density respectively.

Figure 8 demonstrate the impact of \(\Gamma_{1}\)(“Thermal Biot number”) monotonically increases on \(\theta (\eta )\) while reverse trend on \(\theta ^{\prime}(\eta )\). It is clear that, \(\theta (\eta )\) and heat transfer rate are opposite behaviour for enlarge values of \(\Gamma_{1}\). Physically, the thermal Biot number is inversely proportional to thermal conductivity \(k^{*}\). While the behaviour follows impact of \(\Gamma_{2}\)(“Concentration Biot number”) on \(\phi (\eta )\), \(\phi ^{\prime}(\eta )\) as presented in Fig. 9. Physically, \(\Gamma_{2}\) is proportional to wall mass transfer \(k_{m}^{*}\).

Figure 10 determined that the \(\lambda\) (“Williamson parameter”) on \({\text{Re}}_{x}^{1/2} C_{fx}\) with presence and absence of Williamson liquid. It is observed that the skin friction coefficient strictly raises along \(x^{*}\)-directions for ascending values of \(\lambda\). Moreover, in the presence and absence of Williamson fluid against \(M\) along \(x^{*}\) direction. Comparing the presence of \(\alpha\) in Williamson nanofluid flow is better than the absence of \(\alpha\). Physically, \(\lambda\) is proportional to square root of kinematic viscosity \(\upsilon^{*}\). Due to this the low viscosity in Williamson fluid flow generate high skin friction coefficient along \(x^{*}\)-direction.

Figure 11 illustrate that the \(\alpha\)(“Stretching Ratio Parameter”) on \({\text{Re}}_{x}^{1/2} C_{fx}\) with Williamson and nanofluid flow cases. It is clear that the skin friction coefficient monotonically declines along \(x^{*}\) direction for different ascending values of \(\alpha\). We decide, the Williamson liquid is more significant while comparing to nanoliquid motion. Physically, the kinematic viscosity is more in Williamson liquid motion. Due to this, the fluid produces more skin friction in surface.

The numerical results on \(f^{\prime\prime}(0)\) (“Velocity Gradients”) as \(\lambda = 0\) for various values of \(\alpha\) in Table 1. Also, Table 2 exhibited coefficient of skin friction with different results of \(\alpha\) for \(\lambda = 0\). The outcomes are matched with those of Wang 79, Ariel et al. 80. It is noticed that very good agreement up to eight decimal places. Tables 3 and 4 Explored the Heat and Mass Transfer rates with various numerical numbers for \(\alpha = 0\).

Conclusions

This article related to the influence of thermal radiative and heat absorption on 3D Williamson nanoliquid motion via linear stretching surface. It is analyzed numerical technique with 4th order R–K–F (“Runge–Kutta–Fehlberg”) scheme. We have noticed, the main points in present mathematical model as below:

-

The velocity of Williamson nanofluid motion is high when compared to nanofluid motion with high effect of \(M\).

-

Skinfriction coefficient (“along \(x^{*}\)-axis”) is high in absents of \(\alpha\)(“Williamson parameter”) while comparing to presence of \(\alpha\)(“Williamson parameter”) with higher statistical values of \(\lambda\).

-

Skinfriction coefficient (“along \(x^{*}\)-axis”) is high in Williamson liquid motion while comparing to nanoliquid motion with higher statistical values of \(\alpha\).

-

The temperature is high in non-newtonian nanofluid while compared with enhance statistical values.

-

The fluid velocity is higher in Williamson fluid while compared with nanofluid motion. Because of electrical conductivity.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- u1, v1, w1 :

-

Velocity components along x*, y*, z*

- \((x^{*} ,y^{*} )\) :

-

Cartesian coordinate’s

- \(A_{1}\) :

-

First Rivlin-Erickson tensor

- \(C^{*}\) :

-

Nanoparticle volume fraction

- \(C_{f}^{*}\) :

-

Skin friction coefficient

- \(C_{p}^{*}\) :

-

Specific heat

- \(D_{n}\) :

-

Thermal diffusivity

- \(D_{B}\) :

-

Brownian diffusion

- \(D_{T}\) :

-

Thermophoresis diffusion \((m^{2} \,s^{ - 1} )\)

- \(f\) :

-

Dimensionless stream function

- \(f^{^{\prime}}\) :

-

Dimensionless velocity

- \(H\) :

-

Heat absorption \(\frac{{Q_{0} }}{{a_{1} \left( {\rho^{*} C_{p} } \right)_{f} }}\)

- \(k^{*}\) :

-

Mean absorption coefficient

- \(Le\) :

-

Lewis number \(\left( { = \frac{{\alpha_{m}^{*} }}{{D_{B} }}} \right)\)

- \(M\) :

-

Magnetic parameter \(= \left( {\frac{{\sigma^{*} M_{0}^{2} }}{{\rho_{f}^{*} .a_{1} }}} \right)\)

- \(N_{b}\) :

-

Brownian motion coefficient \(= \frac{{\tau^{*} D_{B} \left( {C_{w}^{*} - C_{\infty }^{*} } \right)}}{{\alpha_{m}^{*} }}\)

- \(N_{t}\) :

-

Thermophoresis parameter \(= \frac{{\tau^{*} D_{T} (T_{w}^{*} - T_{\infty }^{*} )}}{{T_{\infty }^{*} \alpha_{m}^{*} }}\)

- \(Nu_{x}\) :

-

Nusselt number

- \(\Pr\) :

-

Prandtl number \(\left( {\upsilon /\alpha_{m} } \right)\)

- \(q_{n}\) :

-

Surface microorganism flux

- \(q_{r}\) :

-

Radiative heat flux \((W\,m^{ - 2} )\)

- \(R_{d}\) :

-

Radiation parameter \(= \frac{{16\sigma^{*} T_{\infty }^{3} }}{{3k^{*} \left( {\rho C_{p} } \right)_{f} }}\)

- \({\text{Re}}_{x}\) :

-

Reynolds number

- \(T^{*}\) :

-

Fluid temperature \((K)\)

- \(T_{w}^{*}\) :

-

Temperature of the fluid

- \(T_{\infty }^{*}\) :

-

Ambient fluid Temperature

- \(\theta\) :

-

Dimensionless temperature

- \(\phi\) :

-

Dimensionless concentration

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Williamson parameter \(\Gamma x^{*} \sqrt {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${2a_{1}^{3} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{2a_{1}^{3} } {\upsilon^{*} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${\upsilon^{*} }$}}}\)

- \(\alpha_{m}^{*}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity \(= \frac{{\mu_{0}^{*} }}{{\rho_{f}^{*} }}\)

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Stretching ratio parameter \(= {\raise0.7ex\hbox{${b_{1} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{b_{1} } {a_{1} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${a_{1} }$}}\)

- \(\sigma^{*}\) :

-

Boltzmann constant \((wm^{ - 2} K^{ - 4} )\)

- \(\mu_{\infty }^{*}\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity at infinite shear rate

- \(\upsilon^{*}\) :

-

Kinematic viscosity \(\left( {\mu_{0}^{*} /\rho_{f}^{*} } \right)\)

- \(\tau^{*}\) :

-

Parameter defined by \(\left( {\rho^{*} C_{p} } \right)\backslash \left( {\rho^{*} C_{f} } \right)\)

- \(\eta\) :

-

Similarity variable

- \(\mu_{0}\) :

-

Limiting viscosity at zero

- \(\tau\) :

-

Extra stress tensor

- \(\rho\) :

-

Fluid density \((Kg\;m^{ - 3} )\)

- \(\Gamma_{1}\) :

-

Thermal Biot Number \({\raise0.7ex\hbox{${h_{1} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{h_{1} } {k_{1}^{*} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${k_{1}^{*} }$}}\)

- \(\Gamma_{2}\) :

-

Concentration Biot Number \({\raise0.7ex\hbox{${h_{2} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{h_{2} } D}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$D$}}\)

- \(\infty\) :

-

Condition at free stream

References

Williamson, R. V. The flow of pseudoplastic materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 21, 1108 (1929).

Nadeem, S., Hussain, T. & Changhoon, L. Flow of a Williamson fluid over a stretching sheet. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 30, 619–625 (2013).

Hayat, T., Saeed, Y., Asad, S. & Alsaedi, A. Soret and dufour effects in the flow of Williamson fluid over an unsteady stretching surface with thermal radiation. Z. Naturforsch 70, 235–243 (2015).

Khan, S. U., Shehzad, S. A. & Ali, N. Interaction of magneto-nanoparticles in Williamson fluid flow over convective oscillatory moving surface. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 40, 1–12 (2018).

Khan, M., Malik, M. Y., Salahuddin, T. & Husaain, A. Heat and mass transfer of Williamson nanofluid flow yield by an inclined Lorentz force over a nonlinear stretching sheet. Results Phys. 8, 862–868 (2018).

Hamid, A. & Khan, M. Unsteady mixed convective flow of Williamson nanofluid with heat transfer in the presence of variable thermal conductivity and magnetic field. J. Mol. Liq. 260, 436–446 (2018).

Hamid, A. & Khan, M. Unsteady stagnation-point flow of Williamson fluid generated by stretching/shrinking sheet with Ohmic heating. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 126, 933–940 (2018).

Monica, M., Sucharitha, J. & KishoreKumar, C. H. Stagnation point flow of a Williamson fluid over a nonlinearly stretching sheet with thermal radiation. Am. Chem. Sci. J. 13, 1–18 (2016).

Hayat, T., Bibi, S., Rafiq, M., Alsaedi, A. & Abbasi, F. M. Effect of an inclined magnetic field on peristaltic flow of Williamson fluid in an inclined channel with convective conditions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 401, 733–745 (2016).

Ellahi, R., Riaz, A. & Nadeem, S. Three-dimensional peristaltic flow of Williamson fluid in a rectangular duct. Indian J. Phys. 87, 1275–1281 (2013).

Rehman, K. U., Khan, A. A., Malik, M. Y., Ali, U. & Naseer, M. Numerical analysis subject to double stratification and chemically reactive species on Williamson dual convection fluid flow yield by an inclined stretching cylindrical surface. Chin. J. Phys. 55, 1637–1652 (2017).

Parmar, A. Unsteady convective boundary layer flow for MHD Williamson fluid over an inclined porous stretching sheet with non-linear radiation and heat source. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 3, S859–S881 (2017).

Sharidan, S. Similiarity solutions for the unsteady boundary layer flow and heat transfer due Toa stretching sheet. Int. J. Appl. Mech. Eng. 11, 647–654 (2006).

Aziz, A., Jamshed, W., Aziz, T., Bahaidarah, H. M. S. & Rehman, K. U. Entropy analysis of powell-eyring hybrid nanofluid including effect of linear thermal radiation and viscous dissipation. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 143, 1331–1343 (2020).

Hussain, S. M. & Jamshed, W. A comparative entropy-based analysis of tangent hyperbolic hybrid nanofluid flow: Implementing finite difference method. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer 129, 105671 (2021).

Bilal, S., Rehman, K. U. & Malik, M. Y. Numerical investigation of thermally stratified Williamson fluid flow over a cylindrical surface via Keller box method. Results Phys. 7, 690–696 (2017).

Malik, M. Y., Bilal, S., Salahuddin, T. & Rehman, K. U. Three-dimensional williamson fluid flow over a linear stretching surface. Math. Sci. Lett. 6, 53–61 (2017).

Xiang, J. et al. Heat transfer performance and structural optimization of a novel micro-channel heat sink. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 35(1), 38 (2022).

Yan, A., Li, Z., Cui, J., Huang, Z., Ni, T., Girard, P. & Wen, X. LDAVPM: A latch design and algorithm-based verification protected against multiple-node-upsets in harsh radiation environments. IEEE Transact. Comput.-Aided Design of Integ. Circuits Syst., 1 (2022).

Tarakaramu, N., Satya Narayana, P. V. & Venkateswarlu, B. Numerical simulation of variable thermal conductivity on 3D flow of nanofluid over a stretching sheet. Nonlinear Eng. 9, 233–243 (2020).

Xiang, J. et al. Design and thermal performance of thermal diode based on the asymmetric flow resistance in vapor channel. Inter. J. Thermal Sci. 191, 108345–108416 (2023).

Jamshed, W. et al. Evaluating the unsteady Casson nanofluid over a stretching sheet with solar thermal radiation: An optimal case study. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 26, 101160 (2021).

Li, L., Liu, W., Wang, Y. & Zhao, Z. Mechanical performance and damage monitoring of CFRP thermoplastic laminates with an open hole repaired by 3D printed patches. Compos. Struct. 303, 116308 (2023).

Mkhatshwa, M. P., Motsa, S. S. & Sibanda, P. Numerical solution of time-dependent Emden-Fowler equations using bivariate spectral collocation method on overlapping grids. Nonlinear Eng. 9, 299–318 (2020).

Yan, A., Li, Z., Cui, J., Huang, Z., Ni, T., Girard, P. & Wen, X. Designs of two quadruple-node-upset self-recoverable latches for highly robust computing in harsh radiation environments. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, 1–13 (2022).

Mishra, S. R., Baag, S., Dash, G. C. & Ranjan Acharya, M. Numerical approach to MHD flow of power-law fluid on a stretching sheet with non-uniform heat source. Nonlinear Eng. 9, 81–93 (2020).

Jamshed, W. et al. Experimental and TDDFT materials simulation of thermal characteristics and entropy optimized of Williamson Cu-methanol and Al2O3-methanol nanofluid flowing through solar collector. Sci. Rep. 12, 18130 (2022).

Aparna, P., Padmaja, P., Pothanna, N. & RamanaMurty, J. V. Couple stress fluid flow due to slow steady oscillations of a permeable sphere. Nonlinear Eng. 9, 352–360 (2020).

Venkateswarlu, A. et al. Significance of magnetic field and chemical reaction on the natural convective flow of hybrid nanofluid by a sphere with viscous dissipation: A statistical approach. Nonlinear Eng. 10, 563–573 (2021).

Jamshed, W. et al. Computational frame work of Cattaneo-Christov heat flux effects on engine oil based Williamson hybrid nanofluids: A thermal case study. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 26, 101179 (2021).

Jamshed, W., Uma Devi, S. & SooppyNisar, K. Single phase-based study of Ag-Cu/EO Williamson hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching surface with shape factor. Phys. Scr. 96, 065202 (2021).

Roberts, P. H. Introduction to Magnetohydrodynamics (Longmans, 1967).

Jamil, M. & Haleem, A. MHD fractionalized Jeffrey fluid over an accelerated slipping porous plate. Nonlinear Eng. 9, 273–289 (2020).

Siddiqa, S. et al. Periodic magnetohydrodynamic natural convection flow of a micropolar fluid with radiation. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 111, 215–222 (2017).

Gireesha, B. J. & Sindhu, S. MHD natural convection flow of Casson fluid in an annular microchannel containing porous medium with heat generation/absorption. Nonlinear Eng. 10, 223–232 (2020).

Yan, A. et al. A novel low-cost TMR-without-voter based HIS-insensitive and MNU-tolerant latch design for aerospace applications. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 56(4), 2666–2676 (2020).

Xiao, D. et al. Wellbore cooling and heat energy utilization method for deep shale gas horizontal well drilling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 213, 118684 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Huang, Z., Wang, F., Li, J. & Wang, H. Design of bioinspired highly aligned bamboo-mimetic metamaterials with structural and functional anisotropy. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2023.3264964 (2023).

Yang, J., Fu, L., Fu, B., Deng, W. & Han, T. Third-order Padé thermoelastic constants of solid rocks. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 127(9), e2022J-e24517J (2022).

Harish Babu, D., SudheerBabu, M. & Satya Narayana, P. V. MHD mass transfer flow of an eyring-powell fluid over a stretching sheet. IOP Conf. Series Mater. Sci. Eng. 263, 1–8 (2017).

Satya Narayana, P. V., Tarakaramu, N., Akshit, S. M. & Ghori, J. P. MHD flow and heat transfer of an eyring–powell fluid over a linear stretching sheet with viscous dissipation-a numerical study. Frontiers Heat Mass Transfer 9, 1–5 (2017).

Jamshed, W., SoopyNisar, K., Punith Gowda, R. J., Naveen Kumar, R. & Prasannakumara, B. C. Radiative heat transfer of second grade nanofluid flow past a porous flat surface: A single-phase mathematical model. Phys. Scr. 96, 064006–064016 (2021).

Bai, X., Shi, H., Zhang, K., Zhang, X. & Wu, Y. Effect of the fit clearance between ceramic outer ring and steel pedestal on the sound radiation of full ceramic ball bearing system. J. Sound Vib. 529, 116967 (2022).

Chen, L. & Zhao, Y. From classical thermodynamics to phase-field method. Prog. Mater Sci. 124, 100868 (2022).

Zou, Q. et al. Thermo-induced structural transformation with synergistic optical and magnetic changes in ytterbium and erbium complexes. Chin. Chem. Lett. 32(4), 1519–1522 (2021).

Bouslimi, J., Alkathiri, A. A., Althagafi, T. M., Jamshed, W. & Eid, M. Thermal properties, flow and comparison between Cu and Ag nanoparticles suspended in sodium alginate as Sutter by nanofluids in solar collector. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 39, 102358 (2022).

He, Y., Zhang, L. & Tong, M. S. Microwave imaging of 3D dielectric-magnetic penetrable objects based on integral equation method. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAP.2023.3262299 (2023).

Tamoor, M., Waqas, M., IjazKhan, M., Alsaedi, A. & Hayat, T. Magnetohydrodynamic flow of Casson fluid over a stretching cylinder. Results Phys. 7, 498–502 (2017).

Devaki, P., Venkateswarlu, B., Srinivas, S. & Sreenadh, S. MHD Peristaltic flow of a nanofluid in a constricted artery for different shapes of nanosized particles. Nonlinear Eng. 9, 51–59 (2020).

Mahabaleshwar, U. S., Sarris, I. E., Hill, A. A., Lorenzini, G. & Pop, I. An MHD couple stress fluid due to a perforated sheet undergoing linear stretching with heat transfer. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 105, 157–167 (2017).

Ali, B., Thumma, T., Habib, D., Salamat, N. & Riaz, S. Finite element analysis on transient MHD 3D rotating flow of Maxwell and tangent hyperbolic nanofluid past a bidirectional stretching sheet with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model. Thermal Sci. Eng. Progress 28, 101089 (2022).

Tarakaramu, N., Satya Narayana, P. V., Harish Babu, D., Sarojamma, G. & Makinde, O. D. Joule heating and dissipation effects on magnetohydrodynamic couple stress nanofluid flow over a bidirectional stretching surface. Int. J. Heat Technol. 39, 205–212 (2020).

Ali, B., Siddique, I., Ahmad, H. & Askar, S., Influence of nanoparticles aggregation and Lorentz force on the dynamics of water-titanium dioxide nanoparticles on a rotating surface using finite element simulation. Sci. Rep., 13 (2023).

Venkateswarlu, B., Satya Narayana, P. V. & Tarakaramu, N. Melting and viscous dissipation effects on MHD flow over a moving surface with constant heat source. Transact. A. Razmadze Math. Inst. 172, 619–630 (2018).

Hazeri-Mahmel, N., Shekari, Y. & Tayebi, A. Three-dimensional analysis of forced convection of Newtonian and non-Newtonian nanofluids through a horizontal pipe using single- and two-phase models. Int. Comm. Heat Mass Transf. 121, 105119 (2021).

Ali, B., Shafiq, A., Siddique, I., Al-Mdallal, Q. & Jarad, F. Significance of suction/injection, gravity modulation, thermal radiation, and magnetohydrodynamic on dynamics of micropolar fluid subject to an inclined sheet via finite element approach. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 28, 101537 (2021).

Tarakaramu, N., Satya Narayana, P. V., Sivakumar, N., Harish Babu, D. & Bhagya Lakshmi, K. Convective conditions on 3D Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) non-newtonian nanofluid flow with nonlinear thermal radiation and heat absorption: A numerical analysis. J. Nanofluid 12, 448–457 (2022).

Fiza, M., Alsubie, A., Ullah H., Hamadneh, N. N., Islam, S. & Khan, I. Three-dimensional rotating flow of MHD Jeffrey fluid flow between two parallel plates with impact of hall current. Math. Prob. Eng., (2021).

Jamshed, W., Eid, M. R., Shahzad, F., Safdar, R. & Shamshuddin, M. D. Keller box analysis for thermal efficiency of magneto time-dependent nanofluid flowing in solar-powered tractor application applying nanometal shaped factor. Waves in Random and Complex Media, (2022).

Tarakaramu, N. et al. Three-dimensional non-Newtonian couple stress fluid flow over a permeable stretching surface with nonlinear thermal radiation and heat source effects. Heat Transf 51, 5348–5367 (2022).

Kim, N. & Reddy, J. N. Least-squares finite element analysis of three-dimensional natural convection of generalized Newtonian fluids. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids. 93, (2020).

Zhao, G. et al. Why the hydrothermal fluorinated method can improve photocatalytic activity of carbon nitride. Chin. Chem. Lett. 32(1), 277–281 (2021).

Ma, Z. H. et al. Alkoxy encapsulation of carbazole-based thermally activated delayed fluorescent dendrimers for highly efficient solution-processed organic light-emitting diodes. Chin. Chem. Lett. 32(2), 703–707 (2021).

Makkar, V. & Batra, P. Three-dimensional modeling of non-Newtonian nanofluid flow in presence of free stream velocity induced by stretching surface. Mater. Today Proc., 63 (2022).

Li, N. F., Lin, Q., Han, Y., Du, Z. & Xu, Y. The chain-shaped coordination polymers based on the bowl-like Ln (18) Ni (24(23.5)) clusters exhibiting favorable low-field magnetocaloric effect. Chin. Chem. Lett. 32(12), 3803–3806 (2021).

Li, P. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of hydrothermally synthesized polycrystalline Te-doped SnSe. Chin. Chem. Lett. 32(2), 811–815 (2021).

Khashi’ie, N. S. et al. Magnetohydrodynamic and viscous dissipation effects on radiative heat transfer of non-Newtonian fluid flow past a nonlinearly shrinking sheet: Reiner-Philippoff model. Alex. Eng. J. 61, 7605–7617 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Investigation of mixed convection of non-Newtonian fluid in the cooling process of lithium-ion battery with different outlet position. J. Energy Storage 46, 103621 (2022).

Sharma, B. K. & Kumawat, C. Impact of temperature dependent viscosity and thermal conductivity on MHD blood flow through a stretching surface with ohmic effect and chemical reaction. Nonlinear Eng. 10, 255–271 (2021).

Satya Narayana, P. V., Akshit, S. M., Ghori, J. P. & Venkateswarlu, B. Thermal radiation effects on an unsteady MHD nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with non-uniform heat source/sink. J. Nanofluids 8, 1–5 (2017).

Kandasamy, R., Dharmalingam, R. & Sivagnana Prabhu, K. K. Thermal and solutal stratification on MHD nanofluid flow over a porous vertical plate. Alexandria Engineering J., 1–10 (2017).

Mehmood, R., Rana, S., Akbar, N.S. & Nadeem, S. Non-aligned stagnation point flow of radiating Casson fluid over a stretching surface. Alexandria Eng. J., 1–8 (2017).

Masthanaiah, Y. et al. Impact of viscous dissipation and entropy generation on cold liquid via channel with porous medium by analytical analysis. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 47, 103059–103116 (2023).

Raju, C. S. K., Hoque, M. M. & Sivasankar, T. Radiative flow of Casson fluid over a moving wedge filled with gyrotactic microorganisms. Adv. Powder Tech. 28, 575–583 (2017).

Ali, B. et al. Significance of Lorentz and Coriolis forces on dynamics of water-based silver tiny particles via finite element simulation. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13, 101572 (2022).

Wang, F. et al. Activation energy on three-dimensional Casson nanofluid motion via stretching sheet: Implementation of Buongiorno’s model. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 100, 100886 (2023).

Uddin, M. J., Sohail, A., Anwar Beg, O., Ismail, A. l. M. Numerical solution of MHD Slip flow of a nanofluid past a radiating plate with Newtonian heating: a lie group approach. Alexandria Eng. J., 1–23 (2017).

Ali, B. et al. Significance of nanoparticle radius and gravity modulation on dynamics of nanofluid over stretched surface via finite element simulation: The case of water-based copper nanoparticles. Mathematics 11, 1266 (2023).

Wang, C. Y. The three-dimensional flow due to a stretching flat surface. Phys. Fluids. 27, 1915 (1984).

Ariel, P. D. The three-dimensional flow past a stretching sheet and the Homotopy Perturbation method. Comput. Math. Appl. 54, 920–925 (2007).

Amanulla, C. H., Nagendra, N., Subba Rao, A., Beg, O. A. & Ali, K. Numerical exploration of thermal radiation and Biot number effects on the flow of a non-Newtonian MHD Williamson fluid over a vertical convective surface. Heat Transfer-Asian Res. 1–19 (2017).

Rao, B. N., Mittal, M. L. & Nataraja, H. R. Hall effect in boundary layer flow. Acta Mech. 49, 147–151 (1983).

Brewster, M. Q. Thermal Radiative Transfer Properties (Wiley, 1972).

Acknowledgements

Research Supporting project number RSP2023R167, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Funding: This Project is founded by king Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors "Mr. Shiva Jagadeesh" contributed the frame of Methodology of problem, "Prof. M. Chenna Krishna Reddy" contributed the calculation of problem, "Dr. Hijaz Ahmad" contributed the graphics drawn and "Dr. Nainaru Tarakaramu" contributed the manuscript written and checking overall manuscript, Dr. Sameh Askar analysed Software and Dr. Sherzod Shukhratovich Abdullaev contributed language quality.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jagadeesh, S., Chenna Krishna Reddy, M., Tarakaramu, N. et al. Convective heat and mass transfer rate on 3D Williamson nanofluid flow via linear stretching sheet with thermal radiation and heat absorption. Sci Rep 13, 9889 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36836-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36836-4

This article is cited by

-

A numerical investigation of the magnetohydrodynamic hybrid nanofluid flow across a convectively heated extending sheet

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (2025)

-

Williamson Nanofluid Heat Analysis Under Power-Law Stretching in Porous Media

International Journal of Applied and Computational Mathematics (2025)

-

Implementation of finite element scheme to study thermal and mass transportation in water-based nanofluid model under quadratic thermal radiation in a disk

Mechanics of Time-Dependent Materials (2024)