Abstract

Soil-transmitted Helminth (STH) infections have been found associated with people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) but little is known about the overall burden of STH coinfection in HIV patients. We aimed to assess the burden of STH infections among HIV patients. Relevant databases were systematically searched for studies reporting the prevalence of soil-transmitted helminthic pathogens in HIV patients. Pooled estimates of each helminthic infection were calculated. The odds ratio was also determined as a measure of the association between STH infection and the HIV status of the patients. Sixty-one studies were finally included in the meta-analysis, consisting of 16,203 human subjects from all over the world. The prevalence of Ascaris lumbricoides infection in HIV patients was found to be 8% (95% CI 0.06, 0.09), the prevalence of Trichuris trichiura infection in HIV patients was found to be 5% (95% CI 0.04, 0.06), the prevalence of hookworm infection in HIV patients was found to be 5% (95% CI 0.04, 0.06), and prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in HIV patients was found to be 5% (95% CI 0.04, 0.05). Countries from Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America & Caribbean and Asia were identified with the highest burden of STH-HIV coinfection. Our analysis indicated that people living with HIV have a higher chance of developing Strongyloides stercoralis infections and decreased odds of developing hookworm infections. Our findings suggest a moderate level of prevalence of STH infections among people living with HIV. The endemicity of STH infections and HIV status both are partially responsible for the burden of STH-HIV coinfections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil-transmitted helminth infections affect nearly 1.5 billion people living in low- and middle-income countries1. These infections are caused by four different pathogens, Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Hookworm, and Strongyloides stercoralis2. Infection with STH is often associated with diarrhoea, anaemia, malnutrition, and stunted growth among children causing substantial morbidity and mortality3,4. A. lumbricoides infection occurs by ingestion of embryonated eggs through contaminated, food, water, and soil. The larvae migrate via the liver and lung, ultimately establishing in the small intestine. The female produces eggs that are passed into the faeces. Symptoms like abdominal stress, diarrhoea, weight loss, and weakness appear only in individuals with a heavy parasitic load. Cognitive impairment in children is often associated with Ascaris infection in endemic areas5,6. The ingested eggs of T. trichiura hatch in the small intestine releasing the larvae which establish as adult worms in the colon. Most individuals with low parasite burden are asymptomatic but those with heavy parasite burden, particularly children can show symptoms of abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea, and rectal prolapse7. Hookworm takes residence in the small intestine attaching itself to the intestinal wall and feeding on the host blood. Blood loss at the attachment site results in iron deficiency anaemia and low haemoglobin levels8. The larvae of S. stercoralis enters via skin penetration and individuals migrate through body tissues, eventually settling in the small intestine where adult female produces eggs. These eggs hatch in the last part of the bowel and they are excreted with faeces. Some of these larvae can autoinfect the host via penetration of perianal skin causing long-term infection of the host. Chronic infections with S. stercoralis are associated with gastrointestinal symptoms—diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and distension, respiratory symptoms—asthma and dyspnoea, skin associated symptoms—itching and urticaria9,10. Socioeconomic status, sanitation, and personal hygiene are common risk factors responsible for the acquisition of STH infections11. The geographical regions of the world, most affected by STHs, are also affected by HIV infections. Currently, 38.4 million people are affected by HIV globally and 650,000 people died from HIV-related causes in 202112. Infection with HIV results in weakened immunity leading to the acquisition of several opportunistic and non-opportunistic pathogens exacerbating the illness13,14. Diarrhoea among HIV patients is often the result of infection with STH pathogens.

Interaction between STHs and their human host might influence susceptibility toward other pathogens. Many reports have suggested that helminth infection contributes to compromised protective immunity against Plasmodium and Mycobacterium15. Despite the high prevalence of STH and HIV infections, the effect of STH infections on HIV acquisition and transmission, disease progression, and management remain inconclusive. It is possible that STH infection contributes to increased susceptibility to HIV infection either directly through an immunological mechanism or indirectly via causing malnutrition16. It has been observed that coinfection with STHs among people living with HIV contributes to exacerbating HIV infection by impairing TH1 immunity which is necessary for clearing the viral load17,18,19. Studies on the effects of deworming, however, present conflicting results. In some reports, it has been observed that deworming did not affect the severity of HIV infection20,21. Others show a reduction in viral load after deworming and a delay in disease progression22,23,24. Infection with both pathogens simultaneously affects the general health and well-being of the patient and timely interventions among the affected population are required for the control of infection. STH infections could be a potential risk factor for HIV acquisition and disease progression and deworming may be a helpful intervention. With a continued focus on the control of HIV and renewed efforts towards the elimination of NTDs as outlined in Sustainable Development Goals, it is crucial to understand the co-prevalence and geographical distribution of STHs and HIV. The goal of the present study is to analyse the global burden of STH infections among HIV patients by systematically reviewing and analysing the literature available on the topic.

Methods

Search strategy

The systematic review was carried out based on PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis) guidelines. Two authors, KA and NS searched PubMed and Web of Science without including a time frame in the literature search up to October 2021 to retrieve studies reporting the prevalence of HIV and any of the STH. The following keywords were used: “HIV” or “AIDS” AND “Helminth” or “Ascaris” or “Whipworm” or “Hookworm” or “Trichuris” or “Necator” or “Ancylostoma” or “Strongyloides” or “Threadworm.” All the studies were transferred to the Zotero citation manager. Initially, the duplicates were removed by the inbuilt feature of Zotero and later by manually screening the remaining studies.

Selection criteria

We searched without any bar on the nature and geographical origin of the studies. Preliminary screening was done based on a review of the title and abstract of the studies. The full text of potentially relevant studies was further screened for data on the prevalence of HIV and STH coinfection. Studies reporting the number or percentage of STHs among HIV patients were considered eligible for data extraction.

Study selection

The quality of the studies included in the final meta-analysis was assessed using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) criteria. The meta-analysis included studies with a rating of 7 or higher. KA carried out the quality assessment which was further verified by NS and FD. All the authors discussed and arrived at a consensus in case of any disagreements.

Data extraction

The data was carefully extracted from the eligible studies and verified by multiple authors to avoid any discrepancies. KA and NS extracted the data while AK, OP, AP, and FD independently verified the extracted data The extracted data included the following information: author, year, study design, location, sample size, helminth prevalence (number or percentage), and diagnostic test for both HIV and the STH pathogens identified.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was done using Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.4. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020. For the determination of pooled prevalence from multiple studies, the random effects model was employed and it was calculated with a 95% confidence interval. Heterogeneity among studies was calculated using Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics, with I2 > 50% considered as significant heterogeneity25. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the source of heterogeneity, stratified by geographical location. Funnel plots were generated to evaluate publication bias.

Results

Initial searches yielded 1567 unique studies out of which the full text of 266 studies was assessed for eligibility. The study selection process was based on PRISMA guidelines (Fig. 1, Supp. Fig. 1). After excluding irrelevant studies and applying the JBI checklist, 61 studies were included in the final systematic review and meta-analysis (Supp. Table 1)26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86. Eleven of the included papers were rated 9 stars i.e., they fulfilled all the criteria mentioned in the JBI checklist, 31 papers were rated 8, and 19 papers were rated 7. Thirteen papers were excluded from the study as they were rated < 7 (supp. Tables 2–3). Thirteen countries from Sub-Saharan Africa (Nigeria, Ethiopia, Mozambique, South Africa, Malawi, Tanzania, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Kenya, Zambia, Uganda, Cameroon, and the Republic of Congo) Three countries from Latin America & Caribbean region (Cuba, Brazil, and Venezuela), seven countries from Asia (Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, India, China, Nepal, and Iran) two countries from Europe and North America (Ireland and the United States of America) reported the prevalence of coinfection with STHs in HIV infected patients (Supp. Table 3). Twenty-four studies reported all four parasites coinfecting HIV-positive patients, 17 studies reported at least three, 9 studies reported at least two, and 11 studies reported a single parasite coinfection associated with HIV-positive patients. The most common method for the diagnosis of HIV infection was ELISA, while all except one study used microscopy as the diagnostic method for parasite detection. Out of 61 studies, fifty-six were carried out after the year 2000 and the earliest reported study was from 1992.

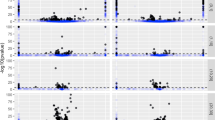

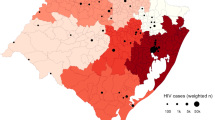

Forty-eight out of 61 selected studies showed the prevalence of HIV/A. lumbricoides coinfection. The estimated pooled prevalence of A. lumbricoides infection was found to be 8% (95% CI 0.06, 0.09) overall, 8% (95% CI 0.06, 0.09) in Sub-Saharan Africa, 6% (95% CI 0.02, 0.09) in Latin America & Caribbean and 11% (95% CI 0.05, 0.16) in Asia (Fig. 2). Thirty-three out of 61 selected studies showed the prevalence of HIV/T. trichiura coinfection. The estimated pooled prevalence was found to be 5% (95% CI 0.04, 0.06) overall, 5% (95% CI 0.04, 0.07) in Sub-Saharan Africa, 5% (95% CI 0, 0.1) in Latin America & Caribbean and 3% (95% CI 0.01, 0.06) in Asia (Fig. 3). Forty-three out of 61 studies showed the prevalence of HIV/ Hookworm coinfection. The estimated pooled prevalence was found to be 5% (95% CI 0.04, 0.06) overall, 5% (95% CI 0.04, 0.06) in Sub-Saharan Africa, 5% (95% CI − 0.01, 0.12) in Latin America & Caribbean and 5% (95% CI 0.02, 0.07) in Asia (Fig. 4). Fifty out of 61 studies showed the prevalence of HIV/S. stercoralis coinfection. The estimated pooled prevalence was found to be 5% (95%CI 0.04, 0.05) overall, 5% (95% CI 0.04, 0.05) in Sub-Saharan Africa, 8% (95% CI 0.02, 0.14) in Latin America & Caribbean, 3% (95% CI 0.01, 0.06) in Asia and 13% (95% CI − 0.09, 0.36) in Europe and North America (Fig. 5). Tanzania, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, and Uganda from Sub-Saharan Africa, India from Asia, and an immigrant sample group in the USA from North America are the only populations that showed a prevalence of 10% or higher for STH infections in people living with HIV (supp. Figs. 2–26, Supp. Table 2). In general, the number of studies reported from Sub-Saharan Africa was more in numbers as compared to Latin America & Caribbean, Asia and Europe, and North America. We did not find any studies from the Middle East and North African region. There was an implication of publication bias as indicated by asymmetrical funnel plots (supp. Figs. 27–30).

We calculated the odds ratio to determine the correlation between HIV infection status and STH infection. The odds did not differ significantly for HIV-positive patients and either A. lumbricoides [OR 0.89 (95% CI 0.73, 1.09)] or T. trichuris coinfections [OR 0.96 (95% CI 0.65, 1.43)] (Supp. Figs. 31–32). HIV infections were associated with decreased odds of hookworm coinfections [OR 0.59 (95% CI 0.38, 0.92)] while HIV infections were associated with more than two-fold increased odds of developing S. stercoralis infections [OR 2.71 (95% CI 1.47, 5.00)] (Supp. Figs. 33–34). A map showing the prevalence of STH infections among HIV patients indicated 0–48% prevalence across 26 countries (Fig. 6).

Discussion

People living with HIV are at a higher risk of developing enteric infections either due to shared epidemiology or dysregulated immunity. These infections hurt the condition of HIV patients contributing to HIV-associated morbidity. Many individual studies have been carried out reporting the prevalence of STH infections among people living with HIV, yet a comprehensive overview of their prevalence has not been analysed. This is the first systematic review to assess the prevalence of the four most important STHs among people living with HIV. After applying the JBI criteria, only 61 studies became eligible for our review. Our analysis indicated a moderate level of prevalence of the four STH pathogens among people living with HIV. Microscopy of stool samples was uniformly used, except in two studies, for the identification of STH infections indicating current infections. A. lumbricoides which is the predominant helminthic infection globally showed the highest prevalence among HIV patients, with Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia showing maximum prevalence which is similar to other reports where the global prevalence was estimated to be 11.01%5. The prevalence among endemic regions as assessed in past studies and our data indicate that HIV infection does not necessarily makes patients more vulnerable to roundworm infection. It is rather associated with the endemicity than the immune status of the patient. Similarly, T. trichiura prevalence also confirms earlier findings with a 15.3% prevalence reported in Asia alone7. Apart from A. lumbricoides all the other three STH indicated an overall prevalence of 5% with a modest difference across population groups. Two studies conducted on immigrants from STH-endemic countries showed a pooled prevalence of 13% of S. stercoralis infections among HIV patients. As HIV infection is associated with impaired immunity which contributes to the development of several opportunistic infections, we determined the odds ratio of developing STH infections among HIV patients. Our analysis indicated that there was no significant association between HIV status and A. lumbricoides and T. trichiura coinfection indicating that infection with both these pathogens is independent of the HIV status of the patients and most likely the result of shared epidemiology. However, we did find a significant association between HIV status and hookworm infection indicating people living with HIV have a decreased risk of developing hookworm infection. These results are consistent with previously published reports where HIV infection was associated with lower hookworm infection rates20,87. This inverse relation between HIV and hookworm in previous studies and our results can be explained by HIV-induced enteropathy that damages the gastrointestinal tract and possibly creates an inhospitable environment for hookworm survival88,89. It was only in the case of S. stercoralis infection that we observed increased odds associated with HIV status. People living with HIV are more than twice likely to develop S. stercoralis infection which is in line with previously published reports about the prevalence and severity of this pathogen in immunosuppressed patients90,91. However, HIV-induced immunosuppression does not lead to disseminated disease or hyperinfection in the case of S. stercoralis infection possibly due to an increase in Th2 cytokines and indirect larval development that reduces the possibility of autoinfection.92,93 Majority of the studies considered in the final analysis were carried out on diverse age groups and both genders consequently gender or age subgroup analysis was not carried out. A few studies reported more than 50% prevalence of STH infection among HIV patients. Both studies by Roka et al. from Guinea, Dwivedi et al. from India, and Mariam et al. from Ethiopia, indicated a preponderance of environmental factors, geographical distribution, and behavioral patterns rather than HIV status as the reason for high prevalence.

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. The review protocol was not registered in International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) as it was overloaded with pandemic related systematic reviews at the time and it would have delayed the registration and review of our protocol94,95. Several potentially relevant studies were identified through a systematic search of the databases but the full text of many of them was not available increasing the possibility of missing out on important data sets. Included data were from 26 countries and mostly concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America & Caribbean, and Asia. Two of the studies reported from Europe and North America tested immigrant populations without any information about their countries of origin and one of them found a very high prevalence of S. stercoralis infection underlining the need for increased attention on such population groups. Many countries and regions remain underrepresented emphasising the need for more robust surveillance of HIV-associated STH infections among people living in these countries. There was not enough data to analyse the correlation of altered CD4+ T cell numbers with the severity of STH or HIV infections, which would have provided evidence for the influence of these infections on each other. Significant heterogeneity was observed which is expected in global prevalence studies across different periods and geographical locations96,97.

Despite the limitations of the present study, it establishes the prevalence of STH infection among HIV patients with a clear link between HIV status and hookworm and S. stercoralis infection and makes the case for deworming as an intervention in STH endemic regions. Future studies are required to assess the long-term impact of STH and HIV coinfection on disease severity, progression, and prognosis.

Conclusion

This is the first study that comprehensively analyses the prevalence of the four most prevalent STH infections among HIV patients showing a moderate level of prevalence. We found that HIV status is associated with increased chances of acquiring S. stercoralis infection and decreased chances of acquiring hookworm infections. People living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America & Caribbean, Asia, and immigrant communities are at a higher risk of developing STH infections. Routine surveillance of HIV-infected people for STH infections should be carried out and provided therapeutic support for the treatment of these infections to improve the health and quality of their life.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

WHO, Soil-transmitted helminth infections, Fact sheet 2022. Soil-transmitted helminth infections. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections. Accessed on August 2nd, 2022

Jourdan, P. M., Lamberton, P. H., Fenwick, A. & Addiss, D. G. Soil-transmitted helminth infections. Lancet 391(10117), 252–265 (2018).

Campbell, S. J. et al. Investigations into the association between soil-transmitted helminth infections, haemoglobin and child development indices in Manufahi District. Timor-Leste. Parasit. Vectors. 10(1), 1–5 (2017).

Soares Magalhães, R. J. & Clements, A. C. Mapping the risk of anaemia in preschool-age children: The contribution of malnutrition, malaria, and helminth infections in West Africa. PLoS Med. 8(6), e1000438 (2011).

Holland, C. et al. Global prevalence of Ascaris infection in humans (2010–2021): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 11(1), 113 (2022).

Else, K. J. et al. Whipworm and roundworm infections. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 6(1), 44 (2020).

Badri, M. et al. The prevalence of human trichuriasis in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol. Res. 121(1), 1 (2022).

Zibaei, M. et al. Insights into hookworm prevalence in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 114(3), 141–154 (2020).

Eslahi, A. V. et al. Global prevalence and epidemiology of Strongyloides stercoralis in dogs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit. Vectors 15(1), 1–3 (2022).

Tamarozzi, F. et al. Morbidity associated with chronic Strongyloides stercoralis infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 100(6), 1305 (2019).

Rahimi, B. A. et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of soil-transmitted helminth infections in Kandahar, Afghanistan. BMC Infect. Dis. 22(1), 1–9 (2022).

WHO, HIV, Fact sheet 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids Accessed on August 2nd, 2022.

Walson, J. L. et al. Prevalence and correlates of helminth co-infection in Kenyan HIV-1 infected adults. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4(3), e644 (2010).

Rubaihayo, J. et al. Frequency and distribution patterns of opportunistic infections associated with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. BMC. Res. Notes 9(1), 1–6 (2016).

Simon, G. G. Impacts of neglected tropical disease on incidence and progression of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria: Scientific links. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 1(42), 54–57 (2016).

Gerns, H. L., Sangaré, L. R. & Walson, J. L. Integration of Deworming into HIV Care and Treatment: A Neglected Opportunity. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6(7), e1738 (2012).

Mulu, A. et al. Effect of deworming on Th2 immune response during HIV-helminths co-infection. J. Transl. Med. 13(1), 1–8 (2015).

Modjarrad, K. & Vermund, S. H. Effect of treating co-infections on HIV-1 viral load: A systematic review. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 10(7), 455–463 (2010).

Abossie, A. & Petros, B. Deworming and the immune status of HIV positive pre-antiretroviral therapy individuals in Arba Minch, Chencha and Gidole hospitals, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 8(1), 1–8 (2015).

Brown, M. et al. Helminth infection is not associated with faster progression of HIV disease in coinfected adults in Uganda. J. Infect. Dis. 190(10), 1869–1879 (2004).

Walson, J. et al. Empiric deworming to delay HIV disease progression in adults with HIV who are ineligible for initiation of antiretroviral treatment (the HEAT study): A multi-site, randomised trial. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 12(12), 925–932 (2012).

Walson, J. L., Herrin, B. R. & John‐Stewart, G. Deworming helminth co‐infected individuals for delaying HIV disease progression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3 (2009).

Wolday, D. et al. Treatment of intestinal worms is associated with decreased HIV plasma viral load. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 31(1), 56–62 (2002).

Webb, E. L. et al. The effect of anthelminthic treatment during pregnancy on HIV plasma viral load; Results from a randomised, double blinded, placebo-controlled trial in Uganda. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 60(3), 307 (2012).

Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. & Altman, D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327(7414), 557–560 (2003).

Abaver, D. T., Nwobegahay, J. M., Goon, D. T., Iweriebor, B. C. & Anye, D. N. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among HIV/AIDS patients from two health institutions in Abuja, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 11, 24–27 (2011).

Akinbo, F. O., Okaka, C. E. & Omoregie, R. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in relation to CD4 counts and anaemia among HIV-infected patients in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. Tanzan J. Health Res. 13(1), 8–13 (2011).

Amoo, J. K. et al. Prevalence of enteric parasitic infections among people living with HIV in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 30, 66 (2018).

Babatunde, S. K., Salami, A. K., Fabiyi, J. P., Agbede, O. O. & Desalu, O. O. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation in HIV seropositive and seronegative patients in Ilorin, Nigeria. Ann. Afr. Med. 9(3), 123–128 (2010).

Ojurongbe, O. et al. Cryptosporidium and other enteric parasitic infections in HIV-seropositive individuals with and without diarrhoea in Osogbo, Nigeria. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 68(2), 75–78 (2011).

Oyedeji, O. A. et al. Intestinal parasitoses in HIV infected children in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 9(11), SC01–SC05 (2015).

Sanyaolu, A. O., Oyibo, W. A., Fagbenro-Beyioku, A. F., Gbadegeshin, A. H. & Iriemenam, N. C. Comparative study of entero-parasitic infections among HIV sero-positive and sero-negative patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Acta Trop. 120(3), 268–272 (2011).

Udeh, E. O., Obiezue, R. N. N., Okafor, F. C., Ikele, C. B., Okoye, I. C. & Otuu, C.A. Gastrointestinal parasitic infections and immunological status of HIV/AIDS coinfected individuals in Nigeria. Ann. Glob. Health 85(1), 99 (2019).

Adamu, H. & Petros, B. Intestinal protozoan infections among HIV positive persons with and without antiretroviral treatment (ART) in selected ART centers in Adama, Afar and Dire-Dawa, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 23(2), 133–140 (2009).

Alemayehu, E. et al. Intestinal parasitic infections among HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy attending Debretabor General Hospital, Northern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 12, 647–655 (2020).

Assefa, S., Erko, B., Medhin, G., Assefa, Z. & Shimelis, T. Intestinal parasitic infections in relation to HIV/AIDS status, Diarrhea and CD4 T-cell count. BMC Infect. Dis. 18(9), 155 (2009).

Eshetu, T. et al. Intestinal parasitosis and their associated factors among people living with HIV at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest-Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 27(4), 411–420 (2017).

Fekadu, S., Taye, K., Teshome, W. & Asnake, S. Prevalence of parasitic infections in HIV-positive patients in Southern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 7(11), 868–872 (2013).

Gedle, D. et al. Intestinal parasitic infections and its association with undernutrition and CD4 T cell levels among HIV/AIDS patients on HAART in Butajira, Ethiopia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. [Internet]. 15, 36 (2017).

Getaneh, A., Medhin, G. & Shimelis, T. Cryptosporidium and strongyloides stercoralis infections among people with and without HIV infection and efficiency of diagnostic methods for Strongyloides in Yirgalem Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. BMC. Res. Notes 1(3), 90 (2010).

Hailegebriel, T., Petros, B. & Endeshaw, T. Evaluation of parasitological methods for the detection of strongyloides stercoralis among individuals in selected health institutions in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 27(5), 515–522 (2017).

Hailemariam, G. et al. Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS and HIV seronegative individuals in a Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 57(2), 41–43 (2004).

Mengist, H. M., Taye, B. & Tsegaye, A. Intestinal parasitosis in relation to CD4+T cells levels and anemia among HAART initiated and HAART naive pediatric HIV patients in a model ART Center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 10(2), 0117715 (2015).

Moges, F. et al. Infection with HIV and intestinal parasites among street dwellers in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 59(6), 400–403 (2006).

Tadesse, A. & Kassu, A. Intestinal parasite isolates in aids patients with chronic Diarrhea in Gondar Teaching Hospital, North West Ethiopia. Ethiop. Med. J. 43(2), 93–96 (2005).

Teklemariam, Z., Abate, D., Mitiku, H. & Dessie, Y. Prevalence of Intestinal parasitic infection among HIV positive persons who are naive and on antiretroviral treatment in Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia. Int. Sch. Res. Notices 2013, 324329 (2013).

Mariam, Z. T., Abebe, G. & Mulu, A. Opportunistic and other intestinal parasitic infections in AIDS patients, HIV seropositive healthy carriers and HIV seronegative individuals in Southwest Ethiopia. East Afr. J. Public Health 5(3), 169–173 (2008).

Zeynudin, A., Hemalatha, K. & Kannan, S. Prevalence of opportunistic intestinal parasitic infection among HIV infected patients who are taking antiretroviral treatment at Jimma Health Center, Jimma, Ethiopia. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 17(4), 513–516 (2013).

Cerveja, B. Z. et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among HIV infected and HIV uninfected patients treated at the 1° De Maio Health Centre in Maputo, Mozambique. EC Microbiol. 9(6), 231–240 (2017).

Adeleke, O. A., Yogeswaran, P. & Wright, G. Intestinal helminth infections amongst HIV-infected adults in Mthatha General Hospital, South Africa. Afr. J. Primary Health Care Fam. Med. 7(1), 910 (2015).

Hosseinipour, M. C. et al. HIV and parasitic infection and the effect of treatment among adult outpatients in Malawi. J. Infect. Dis. 9, 1278–1282 (2007).

Dowling, J. J. et al. Are intestinal helminths a risk factor for non-typhoidal salmonella bacteraemia in adults in Africa who are seropositive for HIV? A case-control study. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 96(2), 203–208 (2002).

Idindili, B. et al. HIV and parasitic co-infections among patients seeking care at health facilities in Tanzania. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 13(4), 75–85 (2011).

Mwambete, K. D., Justin-Temu, M. & Peter, S. Prevalence and management of intestinal helminthiasis among HIV-infected patients at Muhimbili National Hospital. J. Int. Assoc. Phys. AIDS Care 9(3), 150–156 (2002).

Lebbad, M. et al. Intestinal parasites in HIV-2 associated AIDS cases with chronic diarrhoea in Guinea-Bissau. Acta Trop. 1, 45–49 (2001).

Roka, M., Goñi, P., Rubio, E. & Clavel, A. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in HIV-positive patients on the island of Bioko, Equatorial Guinea: Its relation to sanitary conditions and socioeconomic factors. Sci. Total Environ. 15(432), 404–411 (2012).

Roka, M., Goni, P., Rubio, E. & Clavel, A. Intestinal parasites in HIV-seropositive patients in the continental region of equatorial Guinea: Its relation with socio-demographic, health and immune systems factors. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 107(8), 502–510 (2013).

Arndt, M. B. et al. Impact of helminth diagnostic test performance on estimation of risk factors and outcomes in HIV-positive adults. PLoS ONE 8(12), e81915 (2013).

Kipyegen, C. K., Shivairo, R. S. & Odhiambo, R. O. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among HIV Patients in Baringo, Kenya. Pan Afr. Med. J. 13, 37 (2012).

Walson, J. L. et al. Prevalence and correlates of helminth co-infection in Kenyan HIV-1 infected adults. Plos Negl. Trop. Dis. 4(3), e644 (2010).

Chintu, C. et al. Intestinal parasites in HIV-seropositive Zambian children with diarrhoea. J. Trop. Pediatr. 41(3), 149–152 (1995).

Modjarrad, K. et al. Prevalence and predictors of intestinal helminth infections among human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected adults in an urban African setting. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 73(4), 777–782 (2005).

Morawski, B. M. et al. Hookworm infection is associated with decreased CD4+ T cell counts in HIV-infected adult Ugandans. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11(5), 0005634 (2017).

Nkenfou, C. N., Nana, C. T. & Payne, V. K. Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV infected and non-infected patients in a low HIV prevalence region, West-Cameroon. PLoS ONE 8(2), e57914 (2013).

Vouking, M. Z., Enoka, P., Tamo, C. V. & Tadenfok, C. N. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among HIV patients at the Yaoundé Central Hospital, Cameroon. Pan Afr. Med. J. 18, 136 (2014).

Wumba, R. et al. Intestinal parasites infections in hospitalized aids patients in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Parasite 17(4), 321–328 (2010).

Escobedo, A. A. & Nunez, F. A. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in Cuban acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients. Acta Trop. 72(1), 125–130 (1999).

Amancio, F. A. M., Pascotto, V. M., Souza, L. R., Calvi, S. A. & Pereira, P. C. M. Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS patients: Epidemiological, nutritional and immunological aspects. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 18, 225–235 (2012).

Cardoso, L. V. et al. Entericparasites in HIV-1/AIDS-infected patients from a Northwestern Sao Paulo reference unit in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 44(6), 665–669 (2011).

Cimerman, S., Cimerman, B. & Lewi, D. S. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Brazil. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 3(4), 203–206 (1999).

Feitosa, G., Bandeira, A. C., Sampaio, D. P., Badaró, R. & Brites, C. High prevalence of giardiasis and stronglyloidiasis among HIV-infected patients in Bahia, Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Braz. Soc. Infect. Dis. 5(6), 339–344 (2001).

Blatt, M., Jucelene, & Cantos, G. A. Evaluation of techniques for the diagnosis of strongyloides stercoralis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive and HIV negative individuals in the City of Itajaí, Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Braz. Soc. Infect. Dis. 7(6), 402–408 (2003).

Bachur, R. et al. Enteric parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS patients before and after the highly active antiretroviral therapy. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 12(2), 115–122 (2008).

Arenas-Pinto, A. et al. Association between parasitic intestinal infections and acute or chronic diarrhoea in HIV-infected patients in Caracas, Venezuela. Int. J. STD AIDS 14(7), 487–492 (2003).

Chacin-Bonilla, L., Guanipa, N., Cano, G., Raleigh, X. & Quijada, L. Cryptosporidiosis among patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Zulia State, Venezuela. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 47(5), 582–586 (1992).

Paboriboune, P. et al. Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV-infected patients, Lao People’s Democratic Republic. PLoS ONE 9(3), e91452 (2014).

Manatsathit, S. et al. Causes of chronic diarrhea in patients with AIDS in Thailand: A prospective clinical and microbiological study. J. Gastroenterol. 31(4), 533–537 (1996).

Wiwanitkit, V. Intestinal parasitic infections in Thai HIV-infected patients with different immunity status. BMC Gastroenterol. 1, 3 (2001).

Asma, I., Johari, S., Sim, B. L. H. & Lim, Y. A. L. How common is intestinal parasitism in HIV-infected patients in Malaysia?. Trop. Biomed. 28(2), 400–410 (2011).

Dwivedi, K. K. et al. Enteric opportunistic parasites among HIV infected individuals: Associated risk factors and immune status. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 60(2–3), 76–81 (2007).

Janagond, A. B., Sasikala, G., Agatha, D., Ravinder, T. & Thenmozhivalli, P. R. Enteric parasitic infections in relation to diarrhoea in HIV infected individuals with CD4 T cell counts <1000 cells/Μl in Chennai, India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR. 7(10), 2160–2162 (2013).

Tian, L. G. et al. Co-infection of HIV and intestinal parasites in rural area of China. Parasites Vectors 13, 5 (2012).

Tiwari, B. R., Ghimire, P., Malla, S., Sharma, B. & Karki, S. Intestinal parasitic infection among the HIV-infected patients in Nepal. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 7(7), 550–555 (2013).

Zali, M. R. et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic pathogens among HIV-positive individuals in Iran. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 57(6), 268–270 (2004).

Sadlier, C. M., Brown, A., Lambert, J. S., Sheehan, G. & Mallon, P. W. G. Seroprevalence of schistosomiasis and strongyloides infection in HIV-infected patients from endemic areas attending a European Infectious Diseases Clinic. Aids Res. Ther. 8, 10 (2013).

Nabha, L. et al. Prevalence of strongyloides stercoralis in an urban US AIDS cohort. Pathog. Global Health 106(4), 238–244 (2012).

Woodburn, P. W. et al. Risk factors for helminth, malaria, and HIV infection in pregnancy in Entebbe, Uganda. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3(6), e473 (2009).

Brenchley, J. M. & Douek, D. C. HIV infection and the gastrointestinal immune system. Mucosal Immunol. 1(1), 23–30 (2008).

Brown, M., Mawa, P. A., Kaleebu, P. & Elliott, A. M. Helminths and HIV infection: Epidemiological observations on immunological hypotheses. Parasite Immunol. 28(11), 613–623 (2006).

Ahmadpour, E. et al. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients and related risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 66(6), 2233–2243 (2019).

Henriquez‐Camacho, C. A. et al. Ivermectin versus benzimidazoles for treating strongyloides infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016(1), CD007745 (2016).

Schär, F. et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: Global distribution and risk factors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7(7), e2288 (2013).

Viney, M. E. et al. Why does HIV infection not lead to disseminated strongyloidiasis?. J. Infect. Dis. 190(12), 2175–2180 (2004).

Dotto, L. et al. The mass production of systematic reviews about COVID-19: An analysis of PROSPERO records. J. Evid. Based Med. 14(1), 56–64 (2021).

Beresford, L., Walker, R. & Stewart, L. Extent and nature of duplication in PROSPERO using COVID-19-related registrations: A retrospective investigation and survey. BMJ Open 12(12), e061862 (2022).

Wang, Z. D. et al. Prevalence and burden of Toxoplasma gondii infection in HIV-infected people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 4(4), e177–e188 (2017).

Kwatra, G. et al. Prevalence of maternal colonisation with group B streptococcus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. Infect. Dis 16(9), 1076–1084 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.A. and N.S. conceived of the study concept and design. K.A. and N.S. did the literature searches, and analysed the data. K.A., A.K., O.D., A.P., F.D. and N.S. extracted the data and reviewed the manuscript. K.A. and N.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akanksha, K., Kumari, A., Dutta, O. et al. Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infections in HIV patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 13, 11055 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38030-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38030-y

This article is cited by

-

Wastewater-based epidemiological study on helminth egg detection in untreated sewage sludge from Brazilian regions with unequal income

Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2025)

-

Strongyloidiasis

Nature Reviews Disease Primers (2024)