Abstract

Gastric motility is coordinated by bioelectrical slow-wave activity, and abnormal electrical dysrhythmias have been associated with nausea and vomiting. Studies have often been conducted under general anaesthesia, while the impact of general anaesthesia on slow-wave activity has not been studied. Clinical studies have shown that propofol anaesthesia reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) compared with isoflurane, while the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. In this study, we investigated the effects of two anaesthetic drugs, intravenous (IV) propofol and volatile isoflurane, on slow-wave activity. In vivo experiments were performed in female weaner pigs (n = 24). Zolazepam and tiletamine were used to induce general anaesthesia, which was maintained using either IV propofol (n = 12) or isoflurane (n = 12). High-resolution electrical mapping of slow-wave activity was performed. Slow-wave dysrhythmias occurred less often in the propofol group, both in the duration of the recorded period that was dysrhythmic (propofol 14 ± 26%, isoflurane 43 ± 39%, P = 0.043 (Mann–Whitney U test)), and in a case-by-case basis (propofol 3/12, isoflurane 8/12, P = 0.015 (Chi-squared test)). Slow-wave amplitude was similar, while velocity and frequency were higher in the propofol group than the isoflurane group (P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test)). This study presents a potential physiological biomarker linked to recent observations of reduced PONV with IV propofol. The results suggest that propofol is a more suitable anaesthetic for studying slow-wave patterns in vivo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric motility is coordinated, in part, by underlying electrical activity known as slow waves. In the normal stomach, slow waves initiate from a dominant pacemaker site located on the upper corpus on the greater curvature and propagate distally to the terminal antrum1,2. Abnormal ‘dysrhythmic’ slow-wave activity has been implicated in several motility disorders, including gastroparesis3, and chronic nausea and vomiting4,5, fuelling clinical and research interest in these dysrhythmias6,7.

In the past two decades, technological advancement has provided high-resolution mapping of gastrointestinal (GI) slow-wave activity8. Recording and analysis of slow-wave activity, particularly in high-resolution4,9, offers a diagnostic biomarker for GI dysfunction where new biomarkers are critically needed6,10. Slow-wave mapping also underpins the development of potential treatments to modulate slow-wave abnormalities, such as gastric ablation11,12, and pacing13,14.

Invasive high-resolution gastric mapping is typically performed in the anaesthetised state. Despite this, the influence of anaesthetic agents on slow-wave activity, and the possibility of anaesthesia-induced dysrhythmias, remain uncertain. Preliminary studies have shown that gastric and intestinal slow waves show impaired activity following isoflurane anaesthesia15,16,17. In addition, anaesthesia with isoflurane resulted in decreased gastric myoelectric signal power compared to the awake state16. A comparison of gaseous isoflurane and intraperitoneal injection of thiobutabarbital in a rodent model showed that isoflurane resulted in reduced motility18. However, the effects of alternative intravenous (IV) agents on gastric slow waves, such as propofol, have not been evaluated.

Clinical studies have shown that IV propofol reduces the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) compared with isoflurane anaesthesia19,20. As a result, and due to potential immunosuppression advantages21, a shift has been advocated for anaesthesia choices towards total IV anaesthesia (TIVA) using propofol and away from using volatile anaesthetics like isoflurane. However, the physiological mechanisms underlying the reduction of PONV associated with propofol anaesthesia have yet to be established21. Since slow-wave dysrhythmias have been associated with nausea and vomiting4,6,7, it may be hypothesised that anaesthesia-induced dysrhythmias could be a contributing factor to post-surgical dysmotility.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of two widely-used anaesthetic drugs (propofol and isoflurane) on slow-wave activity and compare their impact on gastric slow-wave activity.

Results

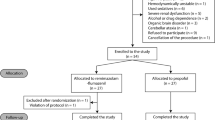

This study comprised a total of 24 animals, with a mean weight of 34.8 ± 4.1 kg. The dataset comprised a total of 200 min of high-resolution electrical mapping, with a mean duration of 8.3 ± 3.0 min per experiment (propofol group 8.1 ± 2.5 min, isoflurane group 8.5 ± 3.6 min, P = 0.407).

Occurrence of Slow-Wave Dysrhythmias

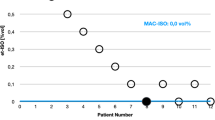

The overall occurrence of dysrhythmias in the propofol group was significantly lower than that of the isoflurane group (propofol: 14 ± 26% of the total recorded duration, median = 0, Q1 = 0, Q3 = 8%; isoflurane: 43 ± 39% of the total recorded duration, median = 33%, Q1 = 0, Q3 = 73%; P = 0.043 (Mann–Whitney U test)).

For cases anaesthetised with propofol, 75% (9/12) demonstrated consistently normal antegrade slow-wave propagation (Table 1, Fig. 1i). The other 25% of cases (3/12) demonstrated dysrhythmic activity for at least a portion of the recording period (Fig. 1ii).

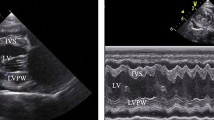

Representative high-resolution slow-wave mapping results of: i. Normal antegrade propagation in a female pig anaesthetised with intravenous (IV) propofol; ii. Dysrhythmic propagation in a female pig anaesthetised with IV propofol. (A,F) Position of the flexible-printed-circuit (FPC) electrode array on the stomach. (B,G) Electrograms from the 8 electrode positions labelled in (C,H), with slow-wave activation times (AT) marked as red dots. (C,H) Isochronal AT map of slow-wave propagation. Each colour band indicates the area of slow-wave propagation per 1 s from red (early) to blue (late). (D,I) Velocity map of the same slow wave, showing the speed (colour spectrum) and direction (arrows) of the wave at each point on the array. (E,J) Amplitude map of the same wave.

In contrast, consistent normal antegrade slow-wave propagation was observed in 33% (4/12) of cases anaesthetised with isoflurane (Table 1, Fig. 2i). The other 67% of cases (8/12) demonstrated dysrhythmic activity for at least a portion of the recording period (Fig. 2ii) (propofol: 3/12 cases demonstrated dysrhythmic activity; isoflurane: 8/12 cases demonstrated dysrhythmic activity; P = 0.015 (Chi-squared test)).

Representative high-resolution slow-wave mapping results of: i. Normal antegrade propagation in a female pig anaesthetised with volatile isoflurane; ii. Dysrhythmic propagation in a female pig anaesthetised with volatile isoflurane. (A,F) Position of the flexible-printed-circuit (FPC) electrode array on the stomach. (B,G) Electrograms from the 8 electrode positions labelled in (C,H), with slow-wave activation times (AT) marked as red dots. (C,H) Isochronal AT map of slow-wave propagation. Each colour band indicates the area of slow-wave propagation per 1 s from red (early) to blue (late). (D,I) Velocity map of the same slow wave, showing the speed (colour spectrum) and direction (arrows) of the wave at each point on the array. (E,J) Amplitude map of the same wave.

Slow-wave Characteristics

Slow-wave amplitude was similar in the propofol and isoflurane groups (propofol: 2.0 ± 0.6 mV vs isoflurane: 1.7 ± 0.5 mV; P = 0.339 (Mann–Whitney U test)) (Fig. 3A). Slow-wave velocity was significantly higher in the propofol group compared to the isoflurane group (propofol: 6.8 ± 1.2 mm/s vs isoflurane: 5.7 ± 0.8 mm/s; P = 0.008 (Student’s t-test)) (Fig. 3B). Slow-wave frequency was also significantly higher in the propofol group compared with the isoflurane group (propofol: 4.4 ± 0.3 cpm vs isoflurane: 3.0 ± 0.8 cpm; P < 0.001 (Student’s t-test)) (Fig. 3C).

Slow-wave characteristics from the in vivo stomach in female pigs anaesthetised by volatile isoflurane (n = 12) versus intravenous (IV) propofol (n = 12). (A) Slow-wave amplitude was similar between isoflurane and propofol. (B) Slow-wave velocity was higher with propofol compared to isoflurane. (C) Slow-wave frequency was also higher with propofol compared to isoflurane. **denotes statistical significance of P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of anaesthetic agents on gastric slow-wave activity. Slow-wave activity in cases anaesthetised with propofol showed significantly less dysrhythmic activity compared to cases anaesthetised with isoflurane (dysrhythmic occurrence of 14 ± 26% vs 43 ± 39%, respectively). In addition, slow-wave activity had significantly higher frequency in the propofol group with lower standard deviation, suggesting increased stability of slow-wave activity with propofol. These results provide a potential physiological biomarker that may help to explain clinical observations of decreased PONV with propofol.

PONV is a common problem encountered in patients following administration of general anaesthesia19,20,22. Traditionally, general anaesthesia is induced and maintained by a combination of volatile and IV agents. However, there is now a trend towards TIVA, supported by findings that TIVA results in reduced rates of PONV, along with other benefits including faster emergence from anaesthesia and reduced incidence of post-operative delirium in elderly patients23,24,25. The mechanisms underlying the observed reduction in PONV remain unclear. Our present study now introduces high-resolution gastric mapping techniques to assess the impact of volatile versus IV anaesthesia. We identified a reduction in gastric electrical dysrhythmias in pigs anaesthetised with propofol compared to isoflurane. The exact mechanisms underlying the increase of dysrhythmia with isoflurane are currently unknown. Potential mechanisms include suppression of ICC entrainment, suppressed vagal activity26, and/or changes to splanchnic blood flow and oxygenation27,28, but future studies are required to identify the underlying mechanisms. Pigs are a common and validated model for gastric physiology8, and gastric electrical dysrhythmias have been associated with nausea and vomiting in humans4,6,29. The findings from this present study introduce gastric dysrhythmias as a physiological biomarker that is consistent with clinical observations of the reduction in PONV incidence following the use of TIVA, therefore providing preliminary evidence that further supports a shift towards TIVA in general anaesthesia.

Our results of reduced dysrhythmias and less variable slow-wave frequency under propofol suggest that propofol is a better anaesthetic option for recording and studying normal rhythmic slow-wave activity. This finding may be particularly relevant for future applications aiming to use slow-wave recordings in human patients for diagnostic and treatment purposes30. However, the higher frequency of slow waves under propofol, compared to EGG results in the porcine model, suggest that propofol may also have an impact on frequency of slow waves31. The reduced incidence of dysrhythmia with propofol is beneficial because inducing dysrhythmia with the anaesthetic agent could impact the diagnostic outcome and subsequently negatively impact potential treatments to eliminate dysrhythmias, such as gastric ablation or gastric pacing11,13. On the contrary, a higher incidence of dysrhythmia when using isoflurane offers a potentially valuable tool for investigators wanting to study abnormal slow-wave activity in research applications, for example, when investigating the feasibility and efficacy of new techniques for detecting or eliminating dysrhythmias29. Our results of dysrhythmia occurrence, frequency, amplitude, and velocity under isoflurane agree with previous studies in the porcine model11,31. In addition, a study using computed-tomography (CT) imaging in a rodent model has shown that isoflurane anaesthesia decreased gastric emptying compared to the non-anaesthetised state32, aligning with our findings of decreased slow-wave frequency with isoflurane.

This study was limited to relatively short-duration recordings of intraoperative slow-wave activity. It has previously been observed that slow-wave stability deteriorates under prolonged anaesthesia by isoflurane33, and we anecdotally observed that slow-wave frequency remained more consistent under propofol, including late in the recording periods34. However, this observation requires verification. To date, human gastric-mapping studies have shown relatively normal gastric slow-wave activity in healthy controls, however most of these studies were performed immediately after induction and laparotomy4,29. Future studies of longer duration recordings, including in the post-operative period, are necessary to understand the full impact of anaesthetic agents during and after surgery. In addition, the slow-wave recording methods in this study were surgically invasive. While these direct-contact measurements enabled accurate dysrhythmia detection, measuring the slow-wave activity of the stomach with less invasive methods, such as body surface29 and/or endoscopic mapping35,36, with accompanying continuous measurement of nausea severity6, would enable the evaluation of gastric slow wave rhythms without surgical intervention. Such approaches would enable the translation of these methods to patients, where the potential role and clinical impact of anaesthesia and dysrhythmias in PONV and post-surgical dysmotility can be investigated.

Methods

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Auckland Animal Ethics Committee (AEC3090 and AEC8158), and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

All experiments were performed in vivo on female crossbreed weaner pigs fasted overnight. All animals were subjected to general anaesthesia with zolazepam and tiletamine (0.1 ml/kg, Zoletil, Virbac, NZ). The first group of animals (propofol group, n = 12) was maintained under anaesthesia with IV propofol (Diprivan 2%, 0.2–0.4 mg/kg/min, AstraZeneca, UK), and the second group of animals (isoflurane group, n = 12) were maintained under anaesthesia with gaseous isoflurane (2.5–5% with an oxygen flow of 400 mL/min within a closed-circuit anaesthetic system).

Vital signs, including heart rate, blood pressure, and rectal temperature, were monitored and maintained within the normal range. A midline laparotomy (10 cm) was performed, and the gastric serosal surface was exposed to enable high-resolution mapping. The subjects of the propofol group were also part of a separate recovery study34, and subjects of the isoflurane group were part of separate acute studies11,12,37. Recordings were consistently performed at the beginning of the initial surgical period in both cohorts prior to any intervention and surgical methods were consistent, except that the propofol group received prophylactic antibiotics by injection immediately prior to the surgery (200 mg/ml, 5 mg/kg, Ceftiofur, Zoetis, NZ). At the conclusion of the experiments, the animals were euthanised with a lethal bolus injection of sodium pentobarbital while still under anaesthesia.

High-resolution mapping

Intraoperative high-resolution electrical mapping was performed using validated flexible-printed-circuit (FPC) electrode arrays (256 electrodes, 16 × 16 array, 4 mm spacing; FlexiMap, NZ)8,9. The FPC array was gently positioned over the corpus and overlain with warm (37 °C) saline-soaked gauze to maintain moisture and gentle pressure of the electrodes onto the serosa. The wound edges were approximated with surgical clamps.

Electrophysiological signal acquisition and analysis

Bioelectrical signals were acquired at 512 Hz using a passive recording system (ActiveTwo, BioSemi, Netherlands). Signal processing and analysis was performed in the Gastrointestinal Electrical Mapping Suite (FlexiMap, Auckland, NZ)38. Data were first down-sampled to 30 Hz before baseline drift was estimated and removed using a Gaussian moving median filter. A Savitzky-Golay filter (‘low-pass’, ~ 2 Hz) was then applied to reduce high-frequency noise39. Slow-wave activation times (AT) were marked and clustered38. Slow-wave propagation was visualised using isochronal AT maps showing the area of propagation per unit of time (Fig. 1)38. Slow-wave amplitude, velocity, and frequency were calculated and mapped.

The occurrence of dysrhythmic activity was calculated as the duration of dysrhythmic activity (e.g., ectopic pacemakers, retrograde propagation, colliding wave fronts, conduction blocks, or electrical quiescence)4,29 divided by the total recorded duration. Each classification of normal versus dysrhythmic activity was subsequently verified by at least three other experienced investigators.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were presented as median, quartiles (Q1 and Q3) and mean ± standard deviation. A normality test (Shapiro–Wilk test) was performed on quantitative data. Based on the result of the normality test, statistical differences were compared using paired Student’s t-test for data that follow a normal distribution, and Mann–Whitney U test for data for data that does not follow a normal distribution. Statistical differences in a case-by-case basis were compared using Chi-squared test. The significance threshold was P < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hirst, G. D. S. An additional role for ICC in the control of gastrointestinal motility?. J. Physiol. 537(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0001k.x (2001).

Huizinga, J. D. & Lammers, W. J. E. P. Gut peristalsis is governed by a multitude of cooperating mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 296(1), G1–G8. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.90380.2008 (2008).

O’Grady, G. et al. Abnormal initiation and conduction of slow-wave activity in gastroparesis, defined by high-resolution electrical mapping. Gastroenterology 143(3), 589-598.e3. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.036 (2012).

Angeli, T. R. et al. Loss of interstitial cells of cajal and patterns of gastric dysrhythmia in patients with chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology 149(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.003 (2015).

Carson, D. A. et al. Abnormalities on electrogastrography in nausea and vomiting syndromes: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and comparison to other gastric disorders. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-07026-x (2021).

Gharibans, A. A. et al. Gastric dysfunction in patients with chronic nausea and vomiting syndromes defined by a noninvasive gastric mapping device. Sci. Transl. Med. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCITRANSLMED.ABQ3544 (2022).

Koch, K. L. Gastric dysrhythmias: A potential objective measure of nausea. Exp. Brain Res. 232(8), 2553–2561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-014-4007-9 (2014).

O’Grady, G. et al. Methods for high-resolution electrical mapping in the gastrointestinal tract. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 12, 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1109/RBME.2018.2867555 (2018).

Du, P. et al. High-resolution mapping of in vivo gastrointestinal slow wave activity using flexible printed circuit board electrodes: Methodology and validation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 37(4), 839–846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-009-9654-9 (2009).

Camilleri, M. & Chedid, V. Actionable biomarkers: The key to resolving disorders of gastrointestinal function. Gut 69(10), 1730–1737. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320325 (2020).

Aghababaie, Z. et al. Targeted ablation of gastric pacemaker sites to modulate patterns of bioelectrical slow wave activation and propagation in an anesthetized pig model. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 322(4), G431–G445. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00332.2021 (2022).

Aghababaie, Z. et al. Gastric ablation as a novel technique for modulating electrical conduction in the in vivo stomach. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 320(4), G573–G585. https://doi.org/10.1152/AJPGI.00448.2020 (2021).

McCallum, R. W. et al. Gastric pacing improves emptying and symptoms in patients with gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 114(3), 456–461 (1998).

Alighaleh, S. et al. A novel gastric pacing device to modulate slow waves and assessment by high-resolution mapping. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 66(10), 2823–2830. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2019.2896624 (2019).

Hou, X., Yin, J., Liu, J., Pasricha, P. J. & Chen, J. D. Z. In vivo gastric and intestinal slow waves in W/Wv mice. Dig Dis Sci. 50(7), 1335–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-005-2783-6 (2005).

Tomaselli, L., Sciullo, M., Fulton, S., et al. Anesthesia suppressed gastric myoelectric power in the ferret. biorxiv.org. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.23.529745

Cheng, W., Chow, B. & Tam, P. K. H. Electrogastrographic changes in children who undergo day-surgery anesthesia. J. Pediatr. Surg. 34(9), 1336–1338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3468(99)90006-4 (1999).

Ailiani, A. C. et al. Quantifying the effects of inactin vs Isoflurane anesthesia on gastrointestinal motility in rats using dynamic magnetic resonance imaging and spatio-temporal maps. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 26(10), 1477–1486. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12410 (2014).

Gecaj-Gashi, A. et al. Propofol vs. isoflurane anesthesia-incidence of PONV in patients at maxillofacial surgery. Adv. Med. Sci. 55(2), 308–312. https://doi.org/10.2478/V10039-010-0033-4 (2010).

Vari, A. et al. Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) after thyroid surgery: A prospective, randomized study comparing totally intravenous versus inhalational anesthetics. Am. Surg. 76(3), 325–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/000313481007600317 (2010).

Kim, R. Effects of surgery and anesthetic choice on immunosuppression and cancer recurrence. J. Transl. Med. 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12967-018-1389-7 (2018).

Schraag, S. et al. Propofol vs. inhalational agents to maintain general anaesthesia in ambulatory and in-patient surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12871-018-0632-3 (2018).

Cai, Y. et al. Association between the apolipoprotein E4 and postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing intravenous anesthesia and inhalation anesthesia. Anesthesiology 116(1), 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0B013E31823DA7A2 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Impact of inhalational versus intravenous anaesthesia on early delirium and long-term survival in elderly patients after cancer surgery: Study protocol of a multicentre, open-label, and randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 7(11), e018607. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2017-018607 (2017).

Apfel, C. C. et al. Volatile anaesthetics may be the main cause of early but not delayed postoperative vomiting: A randomized controlled trial of factorial design. Br. J. Anaesth. 88(5), 659–668. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/88.5.659 (2002).

Toader, E., Cividjian, A. & Quintin, L. Isoflurane suppresses central cardiac parasympathetic activity in rats: A pilot study. Minerva Anestesiol. 77(2), 142–146 (2011).

Aneman, A. et al. Splanchnic and renal sympathetic activity in relation to hemodynamics during isoflurane administration in pigs. Anesth. Analg. 80(1), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-199501000-00023 (1995).

Noldge, G. F. E. et al. Differences in effects of isoflurane and enflurane on splanchnic oxygenation and hepatic metabolism in the pig. Anesth. Analg. 71(3), 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199009000-00008 (1990).

O’Grady, G., Gharibans, A. A., Du, P. & Huizinga, J. D. The gastric conduction system in health and disease: A translational review. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 321(5), G527–G542. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00065.2021 (2021).

Han, X. & Zhu, H. Endoscopic mucosal electrodes: New directions for recording and regulating gastric myoelectric activity. Front. Surg. https://doi.org/10.3389/FSURG.2022.1035723 (2022).

Tachecí, I. et al. The effect of general anaesthesia on gastric myoelectric activity in experimental pigs. BMC Gastroenterol. 13(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-13-48/TABLES/1 (2013).

Gómez-Lado, N. et al. Gastrointestinal tracking and gastric emptying of coated capsules in rats with or without sedation using CT imaging. Pharmaceutics 12(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/PHARMACEUTICS12010081 (2020).

Chan, C. H. A. et al. Localized gastric distension disrupts slow-wave entrainment leading to temporary ectopic propagation: A high-resolution electrical mapping study. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 321(6), G656–G667. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00219.2021 (2021).

Aghababaie, Z. et al. Localized bioelectrical conduction block from radiofrequency gastric ablation persists after healing: Safety and feasibility in a recovery model. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 323(6), G640. https://doi.org/10.1152/AJPGI.00116.2022 (2022).

Coleski, R. & Hasler, W. L. Directed endoscopic mucosal mapping of normal and dysrhythmic gastric slow waves in healthy humans. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 16(5), 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00542.x (2004).

Angeli, T. R. et al. High-resolution electrical mapping of porcine gastric slow-wave propagation from the mucosal surface. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 29(5), e13010. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13010 (2017).

Matthee, A., Aghababaie, Z., Sands, G.B., Angeli-Gordon, T.R. The Effect of Power-Control and Irrigation Settings on Lesion Size during Radio-Frequency Ablation of Gastric Tissue. in Proc Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc EMBS. (2022) ;2022-July:5004–5007. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC48229.2022.9871022

Yassi, R. et al. The gastrointestinal electrical mapping suite (GEMS): Software for analyzing and visualizing high-resolution (multi-electrode) recordings in spatiotemporal detail. BMC Gastroenterol. 12(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-12-60 (2012).

Paskaranandavadivel, N., O’Grady, G., Du, P. & Cheng, L. K. Comparison of filtering methods for extracellular gastric slow wave recordings. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 25(1), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12012 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Vernon Jensen Unit, University of Auckland, for their assistance with the animal care, and Dr. Andre Eto Modesto and Dr. Sean Seo at the Department of Surgery, University of Auckland, for their assistance with the recovery surgical procedures.

Funding

These studies and/or authors were funded by grants from the New Zealand Health Research Council, Marsden Fund administered by the Royal Society Te Apārangi, and the Healthy Digestion platform of the New Zealand National Science Challenge on High-Value Nutrition. TH-HW was supported by the Douglas Goodfellow Medical Research Fellowship from the Auckland Medical Research Foundation. TRA-G was supported by a Rutherford Discovery Fellowship from the Royal Society Te Apārangi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: Z.A., T.H.-H.W., G.O.G., T.R.A.-G.. Data collection: Z.A., T.H.-H.W., L.A.N., G.O.G., T.R.A.-G. Data analysis: Z.A. Data interpretation: All authors. Drafting of manuscript: Z.A., T.R.A.-G. Critical review of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No commercial financial support was received for any material presented in this paper. GOG and LKC hold intellectual property on gastrointestinal electrophysiology. LKC, NP, and TRA-G are shareholders in FlexiMap Ltd. GOG is a Director and shareholder in the Insides Company and Alimetry Ltd. All authors have read the journal's authorship agreement and policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aghababaie, Z., Wang, T.HH., Nisbet, L.A. et al. Anaesthesia by intravenous propofol reduces the incidence of intra-operative gastric electrical slow-wave dysrhythmias compared to isoflurane. Sci Rep 13, 11824 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38612-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38612-w