Abstract

Cadmium lead bismuthate glasses in the system xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3](40 mol% ≤ x ≤ 90 mol%) were successfully prepared by melt-quenching method. The structural and elastic properties have been investigated using XRD, FTIR and ultrasonic pulse–echo techniques. The XRD patterns confirmed the amorphous nature of the samples prepared. Density and ultrasonic velocity data were used to evaluate various elastic properties. Addition of CdO gave rise to decreased density and molar volume and increased elastic moduli, micro-hardness, and Debye temperature. The FTIR analysis revealed that increasing CdO content enhances the BiO6 octahedral sites at the expense of the BiO3 and PbO4 units. This results in the formation of Pb–O–Bi(6) and Bi(3)–O–Bi(6) linkages in the glass network, which stiffen the structure and improve the elastic properties. A correlation between elastic and compositional parameters was achieved on the basis of theories and approaches in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glasses containing heavy metal oxides Bi2O3 and PbO have high refractive index and low melting point. Lead containing glasses find a lot of applications in the field of solder glasses, table wares and optical lenses. Although Bi3+ and Pb2+ ions have the same 6s2 electronic configurations, in toxicity, bismuth is much safer than lead. Bi2O3 is suitable for forming glass with high refractive index, non-toxicity and wide transmission range1. For these reasons, Bi-based glasses can be substituted for the Pb-containing glasses. Now, bismuth-contained glass systems are applied in optical and electronic devices, mechanical sensors, and reflecting windows2,3.

The structural role of Bi2O3 in glasses is complicated because it is not a classical glass former. During recent years, there has been increasing interest in the synthesis, structure and physical properties of heavy metal oxide glasses containing Bi2O3 due to their high refractive index, high infrared transparency, increased third order nonlinear optical susceptibility. Due to the high polarizability and small field strength of Bi3+ ions, a glass network of BiO3 and BiO6 structural units may be built in the presence of SiO2 and B2O34. PbO has dual role in the structure of glasses, one as a glass modifier (if Pb–O is ionic) and the other as glass former (if Pb–O is covalent)5. In a previous study4,6, it has been reported that Bi3+ ions can be present in the glass structure as three [BiO3]—or six [BiO6]-coordinated, existing separately or in the mixture. Meanwhile, Pb2+ ions can be present as three [PbO3]—or four [PbO4]—coordinated.

Cadmium is used as a barrier inside reactors to absorb neutrons and control nuclear fission7. FTIR studies of pure CdO nano-composites revealed an absorption peak around 420 cm−1, which is assigned to the Cd–O bond8. Due to their application in nonlinear optical materials, cadmium-doped glasses have attracted the attention of researchers during recent years7. Glasses from the binary CdO–B2O3 system (CdO = 50–90 mol %) were prepared by melting followed by annealing technique9. The FTIR spectra of these glasses indicated that CdO is consumed in the conversion of some BO3 groups to BO4 groups as many of alkali and alkaline earth oxides. At high CdO content, Cd2+ ions are assumed to behave as modifier besides forming CdO4 groups. Some Nd3+ doped cadmium borate glasses were prepared and characterized optically10. The absorption spectra have been analyzed on the basis of Judd–Ofelt theory. Effect of Na2O on structural and thermal properties of cadmium borate glasses has been investigated by Pavai et al.11,12. XRD and SEM results confirmed the amorphous nature of the glass samples, whereas the FTIR results indicated that the structural role played by Na2O and CdO ions preferentially get incorporated as modifier and former respectively. The influence of CdO and gamma irradiation on the IR absorption spectra of borosilicate glass was investigated12. The infrared results identified the presence of BO3, BO4, SiO4 structural units and B–O–Cd linkages in these glasses. Structure and properties of binary CdO–B2O3 and ternary xCdO·(50−x)MnO·50B2O3 glasses (0 ≤ x ≤ 50 mol%) were extensively studied13. The fraction of four coordinated boron atoms \(\left( {N_{4} } \right)\) was found to be does not change with increasing CdO content. Cadmium-doped lead borate glasses are characterized with the help of IR and Raman spectroscopy14. The conversion of three-fold to four-fold coordination of boron atoms was confirmed. On the other hand, the absence of the IR absorption band at 840/cm suggests that the CdO4 structural units do not formed in these glasses.

Elastic properties are suitable in describing the glass structure as a function of its composition and network connectivity. These properties help in assessing the mechanical strength and structure of glasses. The literature survey indicates that reports on elastic properties of glasses containing CdO are limited. In the current work, for the first time, the structural and elastic properties of cadmium lead bismuthate glasses in the system xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] (40 mol% ≤ x ≤ 90 mol%) have been investigated using XRD, FTIR and ultrasonic pulse-echo techniques. The basic building units in the glass network are identified and the structural changes induced by CdO addition were established. A study on the correlation between elastic and compositional parameters has also been carried out to obtain information regarding the local structure of these glasses.

Experimental

Sample preparation

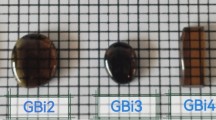

The investigated glass samples in the present study were prepared from laboratory chemicals with purity > 99%, including cadmium carbonate CdCO3 (Fluka, Germany) for CdO, lead tetroxide Pb3O4 (TECHNO FARMACHEM, India) for PbO and Bi2O3 (Fluka, Germany) was added as such. The required amount of different chemicals for producing 100 g glass melt was weighed using a single pan balance having an accuracy of ± 0.001 g. The chemical composition and code of the prepared samples are listed in Table 1. The mixture is put in a porcelain crucible and heated inside a SiC-heated furnace (Vecstar, UK) to 1050 °C for 2 h for melting. The melts were rotated at intervals of 20 min to arrive complete mixing and acceptable homogeneity. The homogeneous molten mixtures were casted into a warmed stainless-steel mold to get the required dimensions. Then the prepared samples were immediately transferred to an annealing muffle furnace regulated at 320 °C—less than the glass transition temperature—to avoid the mechanical strain developed during the quenching process. The muffle was switched off after 1 h and left to cool with the glass inside to room temperature at a rate of 30 °C/h. Finally, the prepared glass samples were polished and their surfaces were made perfectly parallel and smoothened by diamond disc and diamond powder. The samples prepared were non-hygroscopic and chemically stable. Figure 1 shows the photograph of glass samples prepared in the present work.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

The preparedglass samples were subjected to powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), using Bruker AXA diffractometer (Germany) with graphite monochromatized Cu–Kα radiation operating at 40 kV and 10 mA and scanning rate 10°/min was used for x-ray measurements. The measurements were carried out in the range 5° ≤ \(2\theta\) ≥ 80°.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) absorption measurements

FTIR technique is one of the spectroscopic techniques used to identify the basic building units in the glass network. FTIR absorption spectra of glasses prepared were recorded at room temperature in the wave number range from 400 to 1500/cm by a Fourier transform computerized IR spectrometer type FTIR 4600 JASCO Corp (Japan) using the KBr disc technique. The glasses were examined in the form of pulverized powder which was mixed with KBr with the ratio 1:100 mg glass powder to KBr, respectively. The weighed mixtures were then subjected to a pressure of 5 tons/cm2 to produce clear homogeneous discs.

Density measurement and molar volume calculation

The densities of the samples that were prepared were determined at room temperature using an analytical balance A&D company limited, model GR-200, with a repeatability of 0.1 mg, and a density determination kit based on the standard test method ASTM-D792-13. The Archimedes technique was used, with distilled water as the buoyant liquid, and the following formula was applied:

where ρw represents the density of distilled water at room temperature, while Wa and Ww represent the weights of the sample in air and distilled water, respectively. In order to assess the uncertainty associated with the density (ρ) and molar volume (Vm), three measurements were taken for each sample. The formula used to determine the uncertainty in densities and molar volume is based on the standard deviation (σ) and the number of independent observations (n). The standard uncertainty can be calculated using the following expression15: \(u = \frac{\sigma }{\sqrt n }\). Empirical densities (crystalline densities) were calculated using equation \(\rho_{C} = \sum\limits_{i} {x_{i} \,\rho_{i} }\), where \(\rho_{i}\) is the density of ith oxide component in the crystalline phase and \(x_{i}\) is its molar fraction. The molar volume deals directly with the spatial structure of the glass network. The molar volume of each glass sample was calculated with the help of the following equation:

where \(M_{i}\) is the ith component molecular weight. The volume occupied by crystalline phases in the glass network is known as empirical (crystalline) molar volume. Assuming the mixture of oxide components to be an ideal solution we also calculated the empirical molar volume for each glass composition using the relation \(V_{C} = \sum\limits_{i} {x_{i} \,M_{i} /\rho_{i} }\).

Ultrasonic measurements

The ultrasonic pulse-echo technique is a non-damaging technique that capable of determining elastic properties of glasses. The measurements of longitudinal and shear ultrasonic wave velocities in the prepared glass samples were made at room temperature and at 4 MHz frequency. The ultrasonic pulse travels through the sample bonded to the transducer and the echo is registered each time it returns to the transducer. The flaw detector (KRAUTKRAMER USM 36) was applied to measure the time interval between the pulse and its echo (or two successive echoes) (\(\Delta \,t\)). Ultrasonic velocities were determined by dividing the thickness of the sample by \(\Delta \,t\).

Elastic properties are informative because they are related to the structure of the glass network. The ultrasonic velocities and density data allow the determination of various elastic properties using the standard relations; longitudinal modulus \(L = \rho \,V_{\ell }^{{^{2} }}\), shear modulus \(S = \rho \,V_{s}^{{^{2} }}\), bulk modulus \(K = \rho \,\left( {V_{\ell }^{2} - \frac{4}{3}\,V_{s}^{2} } \right)\), Poisson’s ratio \(\mu = \frac{(L - 2\,S)}{{2(L - S)}}\), Young’s modulus \(E = 2\,S(1 + \mu_{\exp } )\), Micro-hardness \(H = \frac{S}{3}(1 - 2\mu_{\exp } )\) and Debye temperature \(\theta_{D} = \frac{h}{B}\left[ {\frac{{3\,\,N_{a} \,}}{{4\,\pi \,\,\overline{V}\,}}} \right]^{\frac{1}{3}} V_{mean}\). In these relations, \(V_{l}^{{}}\) and \(V_{s}\) are the respective longitudinal and shear ultrasonic velocities, \(N_{a}\) is Avogadro’s number, \(B\) is Boltzmann’s constant, \(h\) is Planck’s constant and \(V_{{mean}} = \left[ {\frac{1}{3}\left( {\frac{1}{{V_{\ell }^{3} }}{\text{ + }}\frac{{\text{2}}}{{{\text{V}}_{{\text{s}}}^{{\text{3}}} }}} \right)} \right]^{{^{ - } \frac{1}{3}}}\) is the mean ultrasonic velocity.

Results and discussion

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

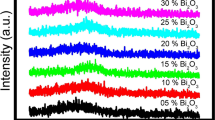

X-ray diffraction is one of the simplest techniques, which was used by researchers to establish the amorphous nature of oxide glasses16. Figure 2 depicts the X-ray diffraction patterns for Cd40, Cd70 and Cd90 glass samples. The absence of sharp Bragg peaks and presence of broad humps confirms the amorphous nature of these samples 16. The samples lack in long-range atomic periodicity in their networks.

FTIR spectral analysis

IR spectroscopy studies were used to get essential information about the arrangement of the structural units of the glass samples. Figure 3 shows the measured FTIR absorption spectra of xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO−0.5Bi2O3] glass samples under investigation. These spectra are dominated by two broad absorption bands in the range 400–550/cm and 750–1050/cm and a small but well-distinguished band centered at 717/cm. The broad band extending from 400 to 550/cm is attributed to bending vibration of Bi–O bonds in BiO6 octahedral units and symmetric bending vibration of Pb–O bonds in PbO4 tetragonal pyramids17,18. The presence of this band confirms the former role of PbO and Bi2O3 in the matrix of the studied glasses. Some author’s attributed the FTIR band at 720/cm in the ZnO modified bismuth silicate glasses19 and that at 715/cm in ternary Bi2O3–B2O3–CuO glasses20 to the symmetric stretching vibrations of Bi–O bond in BiO3 structural units. The appearance of this band in investigated glasses at 717/cm (Fig. 3) evidences the existence Bi3+ ions not only as BiO6 units but also as BiO3 units. The broad band in the wavenumber range 750–1050/cm is assigned to the vibrations of Bi–O–Bilinkages19. With increasing CdO content, the intensity of this band has been observed to increase whereas that of BiO3 units decreases. This suggests that the gradual increase in the concentration of cadmium oxide in xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO−0.5Bi2O3] glasses enhances the BiO6 octahedral sites in the glass matrix at the expense of BiO3 groups. The low frequency peak at 418/cm, which was observed in all samples is may be attributed to vibrations of Cd2+ metal cations.

Because the observed bands are very broad and asymmetric, the deconvolution process should be applied to the measured FTIR spectra to decompose each broad absorption band to deconvoluted peaks (component bands). Each peak has two characteristic parameters, which are the center (C) and the relative area (A). The center is related to some type of vibrations of a specific structural group, whereas the relative area (A) is proportional to the concentration of this structural group. Figure 4 displays the deconvoluted peaks for Cd40, Cd80 and Cd90 glass samples. The Gaussian distribution was applied in the present deconvolution. The peak centers and their corresponding assignments are shown in Table 2.

The general characteristics of the fitted FTIR absorption spectra for the investigated xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses can be summarized as follows;

-

1.

The broad band extending from 400 to 550/cm was deconvoluted to two peaks at about 428 and 476/cm, which are related to BiO6 and PbO4 units, respectively. The intensity of these peak has been observed to increase with increasing CdO.

-

2.

The broad band extending from 550 to 1100/cm was deconvoluted to four peaks at about 690, 733, 831 and 916/cm. An additional absorption peak centered at 636/cm was observed only in Cd90 sample. This may be attributed to the metal–oxygen starching of CdO. The peak centered at 620/cm has been assigned to Cd–O bonds23.

The most important condition for the formation of BiO3 structural units in the glass network is the appearance of the 830/cm band in the FTIR spectra17. In the present study, this band appears in the wave number range 831–843/cm, which proofs the coexistence of BiO6 and BiO3 units in the structure of xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses. Figure 5 shows that the relative area of BiO3- and PbO4—relating absorption bands decrease whereas that of bands characterizing BiO6 units and Pb–O–Bi(6), and Bi(3)–O–Bi(6) linkages increase with the addition CdO. This may be explained by accepting the assumption that the addition of the cadmium oxide declines the formation of BiO3 and PbO4 units in favor of the formation of BiO6 units in the glass. The presence of extra BiO6 units and formation of Pb–O–Bi(6), and Bi(3)–O–Bi(6) linkages is expected to increase the compactness of the glass structure with increasing CdO content. This reflected the glass modifier role of CdO, which results in the change in the coordination number of bismuth ions from three to six. The structure of the studied glasses is assumed to be built up by BiO3, BiO6, and PbO4 structural units. These structural units are connected to each other through Pb–O–Bi, and Bi–O–Bi linkages.

Density and molar volume

The density is one of the simplest tools used to detect changes in the glass structure26,27,28,29. Also, the molar volume can be preferably used to describe the network structure and the arrangement of the building units in glasses26,27,28,29. Table 3 summarized the physical properties of xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses under investigation. The variation of measured and empirical densities with the molar fraction of CdO is shown in Fig. 6. As clearly observed, the measured density values decrease monotonically from 7.4888 to 5.2401 g/cm3 with increasing the molar ratio of CdO from 40 to 90 mol%. This behavior is not only attributed to the lighter molar mass of CdO (128.41 g/mol) than that of Bi2O3 (465.96 g/mol) and PbO (223.20 g/mol) but also attributed to the relative changes in the density values between CdO (8.15 g/cm3), Bi2O3 (8.9 g/cm3) and PbO (9.53 g/cm3). The empirical density values also decreased, but with a slower rate, over the entire composition range studied. As a result \((\rho - \rho_{C} )\) value increases with increasing CdO content, which supports the amorphous nature of samples as confirmed from the XRD results in section “X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis”.

In the present investigation, the molar volume of xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses decreased monotonically from 34.47 to 28.63 cm3/mol with increasing CdO content from 40 to 90 mol% (Fig. 7). The empirical molar volume \(V_{C}\) behaves the same trend but with a higher rate of decrease. This indicates structure compactness with CdO addition. This parallel behavior of density and molar volume with composition was reported in the literature for numerous glasses30,31,32,33. Change in the molar volume might be ascribed to the lattice rearrangements caused by the substitution of PbO and Bi2O3 by CdO resulting in decreasing the ring size, leading to the structural closure. Thus, the decrease in molar volume with increasing CdO content can be explained in two ways as follows:

-

1.

The atomic radii of ingredient elements were changed in the order Cd (1.52 nm) < Pb (1.63 nm) < Bi (1.81 nm). Moreover, the ionic radius values were 0.119 nm for Pb2+ ion and 0.103 nm for Cd2+ and Bi3+ ions. Thus, the substitution of Pb2+ and Bi3+ ions by Cd2+ ion is expected to contracts the structure and decreased the molar volume.

-

2.

Based on FTIR data obtained, the addition of CdO declines the presence of the structural units BiO3 and PbO4 in favor of the presence of BiO6 structural units in the glass network. This results in the formation of Bi(3)–O–Bi(6) and Pb–O–Bi(6) linkages at the expense of Pb–O–Bi(3) linkages. The curves of the radial distribution function (RDF) obtained by the Fourier transformation for PbO–B2O3 glasses concluded that the well-separated peaks due to Pb–O and Pb–Pb correlations appear at about 0.23–0.25 and 0.40 nm, respectively34. Also, X-ray diffraction studies of binary Bi2O3–B2O3 glasses revealed two groups of Bi–O distances at about 0.19 and 0.25 nm35. In the light of these data, the formation of Bi(3)–O–Bi(6) and Pb–O–Bi(6) linkages at the expense of Pb–O–Bi(3) linkages in the present xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses is expected to increase the compactness of their structure and decrease the molar volume.

The increase in the difference between glass and crystalline molar volumes with increasing CdO content in the glass confirms the amorphous nature of samples.

Ultrasonic velocity and elastic properties

Changes in the glass structure due to addition of a network modifier and/or a network former can be directly reflected in ultrasonic velocities and elastic properties. Thus, the composition dependence of ultrasonic velocities and elastic moduli may yield information about the dimensionality and nature of bonding in the glass. The results of longitudinal and shear ultrasonic velocities measurements, along with the determined values of elastic moduli, micro-hardness, Debye temperature and Poison's ratio are listed in Table 4 for xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses studied. One can observe from Fig. 8 that both longitudinal and shear velocities increase linearly with the substitution of (0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3) by CdO. Also, the elastic moduli (Fig. 9) and micro-hardness (Fig. 10) are improved with the progressive addition of CdO. Generally, elastic moduli of the glass are strongly dependent on the concentration of basic structural units of the constituent oxides and types of bonds between these units. The FTIR results obtained indicated that the increase in the concentration of cadmium oxide enhances the BiO6 octahedral sites in the glass matrix at the expense of BiO3and PbO4 groups. As shown in Fig. 5, the relative areas of absorption band characterizing BiO3 and PbO4 units decrease, whereas that of BiO6 units increases. The fraction of the six coordinated bismuth atoms (or fraction of BiO6 units) was calculated from the relation \(N_{6} = A_{6} /\,(A_{3} + A_{6} )\), where \(A_{6}\) is the area under IR peaks characterizing BiO6 and \(A_{3}\) is that under IR peaks characterizing BiO3 units. The \(N_{6}\) values changed from 0.0081 in Cd40 sample to 0.1855 in Cd90 sample as shown Fig. 11. This behavior is quite similar to those of ultrasonic velocities and elastic moduli. It is well known that bulk modulus is a function of the cross-link density (coordination number of a network former cation minus 2) and number of network bonds per unit volume of the glass36. However, the BiO6, PbO4 and BiO3 structural units have a cross-link density of 4, 2 and 1, respectively. Thus, the presence of extra covalent bonds due to the formation of Pb–O–Bi(6) and Bi(3)–O–Bi(6) linkages at the expense of Pb–O–Bi(3) linkages is expected to increase the average cross-link density and number of network bonds per unit volume. This increases the rigidity and resists the deformation of glassy structure with increasing CdO content as evidenced by the increase in ultrasonic velocity, elastic moduli and micro-hardness.

Poisson's ratio plays a dominant role in exploring the degree of connectivity and cross-link density of the glass structure. It is reported that, if the solid material has Poisson’s ratio < 0.3, then it has been counted in high cross-linking density materials37. Otherwise, it is considered in low cross-linking density materials. Three-dimensional glasses (high cross-link density materials) have Poisson’s ratio values extending from 0.1 to 0.2, meanwhile, two-dimensional glasses have Poisson’s ratio values extending from 0.3 to 0.537. It can be seen from Table 3 that xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses have Poisson’s ratio values < 3.0, which suggest that these glasses have high cross-linking density. These cross-links generate covalent bonds and resisting the transverse deformation. This evidenced the presence of PbO4, BiO3 and BiO6structural units within the matrix of these glasses.

Debye temperature is an important thermal parameter in the determination of elastic properties and atomic vibrations of solids. The increasing trend of Debye temperature in xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses (Fig. 12) implies an enhancement in the compactness and rigidity with the substitution of (0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3) by CdO. This behavior is in consistent with the results of molar volume, ultrasonic velocities, elastic moduli, and micro-hardness.

Gopal et al.38 and Rajendran et al.39 suggested bulk modulus—molar volume correlation according to the equation \(K\,V_{M}^{b} = C\). In this relation \(b\) and \(C\) are two constants, their values are determined by the nature of bonding, and co-ordination polyhedral that are present in the glass structure. As shown in Fig. 13, the bulk modulus-molar volume relationship revealed an inverse proportionality for xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses. The equation of the fitted curve is given by \(K\,V_{M}^{3.21} = 5 \times 10^{6}\), with \(b = \,3.21\), \(C\, = \,5\, \times \,10^{6}\) and R2 = 0.963. A good bulk modulus-molar volume correlation was achieved in alkaline earth aluminoborate RO–Al2O3–B2O3 (R = Mg, Ca, Sr) glasses (\(b = \,1.92\) and \(C\, = \,3.7\, \times \,\left. {10^{4} } \right)\)40, TiO2-doped borate CaO–Al2O3–B2O3 glasses (\(b = \,4.38\) and \(C\, = \,8.8\, \times \,1\left. {0^{7} } \right)\)41, fluorotellurite BaF2–TeO2 glasses (\(b = \,1.05\) and \(C\, = \,1.0125\, \times \,\left. {10^{3} } \right)\)42. This dependence of \(b\) and \(C\) values on the glass network supports Gopal et al.38 and Rajendran et al.39 approaches.

Fractal bond connectivity (\(d\, = \,4\,S\,/K\)) can give information about the dimensionality of the glass structure43. This parameter testified the glass rigidity and mostly its values lie between 1 and 3. It has been found that, \(d\, = \,1\) for 1D chain structure, \(d\, = \,2\) for 2D layer network and \(d\, = \,3\) for 3D network43. The \(d\,\) values of the present xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses lie between 1.99 and 2.18, which suggests 2D structures. One way to determine the elasticity of glasses is by studying Poisson’s ratio—fractal bond connectivity correlation on the basis of Abd El-Moneim’s approach44, according to the following equation:

where A and z are two constant, their values depend strongly on the glass network44. Figure 14 shows an inverse linear proportionality between \(\mu \,\) and \(\,d\), which confirms the validity of the semi-empirical Eq. (3) for the present xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses. The equation of the fitted curve in this figure is given by \(\mu \, = 0.468 - \,\,{0}.091\,d\), with R2 = 0.994. The present glasses have A and zvalues agree very well those reported previously for different glasses, like Li2O–V2O5–B2O3 glasses (A = 0.447 and z = 0.082)45, WO3–B2O3–MgO–TeO2 glasses (A = 0.466 and z = 0.09)46, Li2O–PbO–B2O3 glasses (A = 0.469 and z = 0.091)47 and PbO–CuO–B2O3 glasses (A = 0.473 and z = 0.094) glasses48. This supports the suitability of Abd El-Moneim’s approach44 for understanding the Poisson's ratio data of glasses.

Understanding the obtained elastic moduli values of xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses is based on the Makishima–Mackenzie’s theory49,50. It is a well-known fact that closely packed structures are rigid and have high values of packing density, whereas loosely packed structures are soft and have small values of packing density49,50. According to Makishima–Mackenzie's theory49,50, elastic moduli of glasses should show a forward relations with two compositional parameters, which are the total packing density (\(C_{t} = \sum\limits_{i} {x_{i} } C_{i}\), where \(C_{i}\) is the ith oxide component packing density) and total dissociation energy per unit volume (\(G_{t} = \sum\limits_{i} {x_{i} } G_{i}\), where \(G_{i}\) is the ith oxide component dissociation energy per unit volume). The calculated \(C_{t}\) and \(G_{t}\) values for xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses are listed in Table 3. For CdO, PbO and Bi2O3 oxides, we have applied \(C_{i}\) values of 0.5204, 0.3843 and 0.4985, respectively, whereas the applied \(G_{i}\) values were 7.94, 6.05 and 7.56 kcal/cm3 respectively51. It was found that both \(C_{t}\) and \(G_{t}\) show an increase with the substitution of (0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3) mole by mole with CdO. These results agree well with the elastic moduli (Figs. 15 and 16), micro-hardness and Debye temperature results, which suggested an increase in the rigidity of the glass matrix with increasing CdO content. This confirms the applicability of Makishima–Mackenzie theory49,50 for predicting the elastic moduli of the investigated glasses.

The following equation, which correlating bulk modulus with the total packing density and Young’s modulus of ionic solid, was reported49,50:

In these equations, \(m\) and \(n\) are constants in Mie’s atomic potential-energy equation (\(\varphi (r) = - \frac{a}{{r^{m} }} + \frac{b}{{r^{n} }}\),\(a\) and \(b\) are two constants and \(r\) is the distance between cation and anion), \(\beta = {{\left( {r_{A} + r_{O} } \right)^{3} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {r_{A} + r_{O} } \right)^{3} } {\left( {y\,r_{A}^{3} + z\,r_{O}^{3} } \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {y\,r_{A}^{3} + z\,r_{O}^{3} } \right)}}\) is a factor for an oxide \(A_{y} O_{z}\) with cation ionic radius \(r_{A}\) and oxygen ionic radius \(r_{O}\). It is important to demonstrate the applicability of Eq. (4) for the present glasses. Figure 17 shows how the experimental bulk modulus varies with the quantity \(\left( {C_{t\,} E_{\exp } } \right)\). As can be seen, the \(K_{\exp }\)−\(C_{t\,} E_{\exp }\) relationship reveals a linear proportionality. The fitted curve in the figure can be represented by the following semi-empirical formula:

with R2 = 0.996 and \(\left[ {(m - n)\,m/24\pi } \right]\,\beta \,\, = 1.49\). These results show that the correlation between bulk and Young’s moduli of xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] glasses can be achieved through the total theoretical packing density.

Conclusions

Cadmium lead bismuthate glasses in the system xCdO–(1−x)[0.5PbO + 0.5Bi2O3] (40 mol% ≤ x ≤ 90 mol%) were successfully prepared and their properties are characterized using XRD, FTIR and ultrasonic pulse-echo techniques. The inclusion of CdO has linearly decreased the ultrasonic velocity, elastic moduli, micro-hardness and Debye temperature increase show a linear increase. FTIR analysis clearly suggested that CdO plays a network modifier role, whereas Bi2O3 and PbO both play the role of network formers. The presence of BiO3 and PbO4 units is declined in favor of the presence of BiO6 units as CdO content increases. This modified the structure and increased the cross-link density and rigidity of the glass. Finally, a good correlation was achieved between elastic moduli and the most significant compositional parameters, like molar volume, fractal bond connectivity, packing density and dissociation energy per unit volume.

Data availability

No data associated in the manuscript. All original data supporting figures and discussion are listed in the Tables, which are included in the manuscript.

References

Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Zheng, J., Hua, W. & Chen, G. Effects of oxidizing additives on optical properties of Bi2O3-B2O3-SiO2 glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 91, 3410 (2008).

Oprea, I. I., Hesse, H. & Betzler, K. Optical properties of bismuth borate glasses. Opt. Mater. (Amst.) 26, 235–237 (2004).

Łaczka, M., Stoch, L. & Górecki, J. Bismuth-containing glasses as materials for optoelectronics. J. Alloys Compd. 186, 279 (1992).

Zhang, Y. & Guo, T. Study on the sealing glass of lower melting point in system Li2O–ZnO–SiO2. Vacuum Electron. 2, 43–45 (2006).

Rami-Reddy, M., Bangaru-Raju, S. & Veeraiah, N. Acoustic investigations on PbO-Al2O3-B2O3 glasses doped with certain rare earth ions. Bull. Mater. Sci. 24, 63–68 (2001).

Naidu, M. D. & Ratnakaram, Y. C. Pr3+-doped strontium–aluminum–bismuth–borate glasses for laser applications. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 86, 690 (2019).

Mahmoud, K. A., Tashlykov, O. L., Sayyed, M. I. & Kavaz, E. The role of cadmium oxides in the enhancement of radiation shielding capacities for alkali borate glasses. Ceram. Int. 46, 2337 (2020).

Prakash, T., Arunkumar, T., Raj, D. S. & Jayaprakash, R. Surfactant-liaised variation in CdO nanocomposites morphology. Phys. Procedia 49, 36–43 (2013).

Azooz, M. A., Ouis, M. A. & ElBatal, H. A. Preparation and characterization of invert glasses with high CdO content. J. Non Cryst. Solids 515, 82–87 (2019).

Sharma, Y. K., Joshi, R. P. & Goyal, P. Optical band gap and physical properties of Nd3+ doped cadmium borate glasses. Am. J. Phys. Appl. 2, 162–166 (2014).

Pavai, R. E. & Dharsini, P. S. Effect of Na2O on structural and thermal properties of cadmium borate glasses. IOSR J. App. Phys. 9, 67–70 (2017).

Kaur, R., Singh, S. & Pandey, O. P. Influence of CdO and gamma irradiation on the infrared absorption spectra of borosilicate glass. J. Mol. Struct. 1049, 409–413 (2013).

Doweidar, H., El-Damrawi, G. & El-Stohy, S. Structure and properties of CdO–B2O3 and CdO–MnO–B2O3 glasses; criteria of getting the fraction of four coordinated boron atoms from infrared spectra. Phys. B Condens. Matter 525, 137–143 (2017).

Alemi, A. A., Sedghi, H., Mirmohseni, A. R. & Golsanamlu, V. Synthesis and characterization of cadmium doped lead-borate glasses. Bull. Mater. Sci. 29, 55 (2006).

Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, E. of M. D. Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (JCGM 100: 2008) (2008).

Barde, R. V. & Waghuley, S. A. Thermal and electrical properties of 60V2O5–5P2O5-(35–x)B2O3 -xCeO2(1 ≤ x ≤ 5) glasses. Bull. Mater. Sci. 38, 557–583 (2015).

Bahari, H., Aziz, S. H. A., Kamari, H. M., Yunus, W. M. M. & Adikan, F. R. M. The effect of bismuth on the structure and mechanical properties of GeO2-PbO-Bi2O3 ternary bulk glass system. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 120, 280–285 (2012).

Pascuta, P. & Culea, E. FTIR spectroscopic study of some bismuth germanate glasses containing gadolinium ions. Mater. Lett. 62, 4127 (2008).

Hooda, J., Punia, R., Kundu, R. S., Dhankhar, S. & Kishore, N. Structural and physical properties of ZnO modified bismuth silicate glasses. ISRN Spectrosc. 2012, 1–5 (2012).

Ardelean, I., Cora, S. & Rusu, D. EPR and FT-IR spectroscopic studies of Bi2O3- B2O3- CuO glasses. Phys. B Condens. Matter 403, 3682 (2008).

Shaaban, K. S., Abd-Allah, W. M. & Saddeek, Y. B. Gamma rays interactions with CdO-doped lead silicate glasses. Opt. Quant. Electron. 52, 1 (2020).

Abdel-Aziz, A. M. et al. Physical, FTIR, ultrasonic, and dielectric characteristics of calcium lead-borate glasses mixed by Nd2O3/Er2O3 rare earths: Experimental study. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 32, 19966 (2021).

Doweidar, H. & Saddeek, Y. B. FTIR and ultrasonic investigations on modified bismuth borate glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids 355, 348–354 (2009).

Tripathi, R., Dutta, A., Das, S., Kumar, A. & Sinha, T. P. Dielectric relaxation of CdO nanoparticles. Appl. Nanosci. (Switzerl.) 6, 175–181 (2016).

Bosca, M., Pop, L., Borodi, G., Pascuta, P. & Culea, E. XRD and FTIR structural investigations of erbium-doped bismuth-lead-silver glasses and glass ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 479, 582 (2009).

Algradee, M. A., Saleh, E. E., Samir, O. M., Alwany, A. B. & El-Sherbini, T. M. Physical, structural, optical, and gamma ray shielding properties of Li2O–ZnO–SiO2–P2O5 glasses doped with Nd2O3. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 128, 11 (2022).

Algradee, M. A., Alwany, A. B., Samir, O. M., Saleh, E. E. & El Sherbini, T. M. Structural, physical and optical properties of ZnO-V2O5-P2O5 glass system. J. Non Cryst. Solids 589, 1216 (2022).

Barde, R. V. & Waghuley, S. A. Transport and physical properties of V2O5-P2O5-B2O3 glasses doped with Dy2O3. J. Adv. Ceram. 2, 246 (2013).

Barde, R. V. & Waghuley, S. A. Preparation and electrical conductivity of novel vanadate borate glass system containing graphene oxide. J. Non Cryst. Solids 376, 117 (2013).

El-Egili, K. & Oraby, A. H. The structure and electrical properties of lithium borate glasses containing thallic oxide. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 8, 46 (1996).

Rao, K. J. Structural chemistry of glasses. Struct. Chem. Glass. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-043958-7.x5017-1 (2002).

Saddeek, Y. B. & Latif, L. A. E. Effect of TeO2 on the elastic moduli of sodium borate glasses. Phys. B Condens. Matter 348, 475–484 (2004).

Moustafa, E. S., Saddeek, Y. B. & Shaaban, E. R. Structural and optical properties of lithium borobismuthate glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 69, 2281–2287 (2008).

Takaishi, T., Jin, J., Uchino, T. & Yoko, T. Structural study of PbO-B2O3 glasses by X-ray diffraction and 11B MAS NMR techniques. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 83, 10 (2000).

Feller, S. A., Hannon, A. C. & Wright, A. C. Borate Glasses, Crystal & Melts (Society of glass technology, 1997).

Yao, Z. Y. et al. Structure and mechanical properties of copper-lead and copper-zinc borate glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids 435, 55–68 (2016).

Bridge, B., Patel, N. D. & Waters, D. N. On the elastic constants and structure of the pure inorganic oxide glasses. Phys. Status Solidi A 77, 655–668 (1983).

Gopal, E. S. R., Mukundan, T. S., Philip, J. & Sathish, S. Low temperature elastic behaviour of As-Sb-Se and Ge-Sb-Se glasses. Pramana 28, 471–482 (1987).

Rajendran, V., Palanivelu, N., Modak, D. K. & Chaudhuri, B. K. Ultrasonic investigation on ferroelectric BaTiO3 doped 80V2O5–20PbO oxide glasses. Phys. Status Solidi A Appl. Res. 180, 896 (2000).

Abd-El-Moneim, A., Youssof, I. M. & Abd-El-Latif, L. Structural role of RO and Al2O3 in borate glasses using an ultrasonic technique. Acta Mater. 54, 3811–3819 (2006).

Abd-El-Moneim, A. Correlations between ultrasonic and structural properties of 38·1CaO–20·9Al2O3–41B2O3+ 0 ≤ TiO2 ≤ 6· 3 glasses. Phys. Chem. Glass. 46, 267–273 (2005).

Abd El-Moneim, A. BaF2–contained tellurite glasses: Quantitative analysis and prediction of elastic properties and ultrasonic attenuation–Part I. J. Fluor. Chem. 210, 156–165 (2018).

Bogue, R. & Sladek, R. J. Elasticity and thermal expansivity of (AgI)x(AgPO3)1–x glasses. Phys. Rev. B 42, 89 (1990).

El-Moneim, A. A. Tellurite glasses: Correlations between elastic moduli and compositional parameters. Phys. Chem. Glass. Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. Part B 50, 407–417 (2009).

El-Moneim, A. A. Prediction of elastic properties in oxide glasses: Extension of Abd El-Moneim and Alfifi’s approaches to lithium borovanadate glasses. Phys. Chem. Glass. Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. Part B 60, 70–77 (2019).

El-Moneim, A. A. & El-Mallawany, R. Analysis and prediction for elastic properties of quaternary tellurite Ag2O–V2O5–MoO3–TeO2 and WO3–B2O3–MgO–TeO2 glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids 522, 119580 (2019).

El-Moneim, A. A., Eltohamy, M. & Albetran, H. M. Quantitative analysis and prediction for acoustical properties of alkali borate glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids 563, 120826 (2021).

El-Moneim, A. A., Eltohamy, M., Afifi, H., Gaafar, M. S. & Atef, A. An ultrasonic study on ternary xPbO–(45–x)CuO–55B2O3 glasses. Ceram. Int. 47, 27351–27360 (2021).

Makishima, A. & Mackenzie, J. D. Direct calculation of Young’s moidulus of glass. J. Non Cryst. Solids 12, 35–45 (1973).

Makishima, A. & Mackenzie, J. D. Calculation of bulk modulus, shear modulus and Poisson’s ratio of glass. J. Non Cryst. Solids 17, 147–157 (1975).

Inaba, S., Oda, S. & Morinaga, K. Heat capacity of oxide glasses at high temperature region. J. Non Cryst. Solids 325, 258–266 (2003).

Acknowledgements

One of the authors, Amin Abd El-Moneim, wishes to thank Professor M. S. Gaafar, National Institute for Standards, Tersa Street, El-Haram, Giza, Egypt, for his cooperation and helpful discussion of FTIR results.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.E.: investigation, software, validation, visualization, writing—review & editing. M.A.A.: conceptualization, methodology, software, writing—review & editing. H.A.H.: conceptualization, investigation, validation, formal analysis, writing—review & editing. A.M.F.: data curation, writing—original draft. R.L.E.: data curation, writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abd El-Moneim, A., Azooz, M.A., Hashem, H.A. et al. XRD, FTIR and ultrasonic investigations of cadmium lead bismuthate glasses. Sci Rep 13, 12788 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39489-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39489-5

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis Of Novel Bi2O3/ZnO Nanocomposite By Hydrothermal Method: A Sustainable Solution for Photocatalytic Malachite Green and Acid Blue 113 Dye Degradation

Chemistry Africa (2025)

-

Fabrication of rGO decorated CdO nanocomposite for enhanced performance of supercapacitor

Interactions (2025)

-

Impact of Sm3+ ions on the structure, physical, FTIR spectroscopy and mechano-radiation shielding capabilities of high dense CdO–Bi2O3–SiO2 glasses

Applied Physics A (2025)

-

Bario-Silicate Glasses Reinforced With Cadmium Oxide: Physical, Mechanical Properties and Gamma Radiation Shielding Competence

Silicon (2025)

-

Predicting Structure-Mechanical and Thermal Properties Relationships for Cadmium-Borate Glasses

Journal of Electronic Materials (2025)