Abstract

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening condition. Accurate judgement of the disease progression is essential for controlling the condition in ARDS patients. We investigated whether changes in the level of serum sRAGE/esRAGE could predict the 28-day mortality of ICU patients with ARDS. A total of 83 ARDS patients in the ICU of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University from January 2021 to June 2022 were consecutively enrolled in this study. Demographic data, primary diagnosis and comorbidities were obtained. Multiple scoring systems, real-time monitoring systems, and biological indicators were determined within 6 h of admission. The clinical parameters for survival status of the ARDS patients were identified by multivariate logistic regression. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to verify the accuracy of the prognosis of the related parameters. The admission level of sRAGE was significantly higher in the nonsurvival group than in the survival group (p < 0.05), whereas the serum esRAGE level showed the opposite trend. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that sRAGE (AUC 0.673, p < 0.05), esRAGE (AUC 0.704, p < 0.05), and ELWI (extravascular lung water index) (AUC 0.717, p < 0.05) were independent risk factors for the prognosis of ARDS. Model B (ELWI + esRAGE) could not be built as a valid linear regression model (ELWI, p = 0.079 > 0.05). Model C (esRAGE + sRAGE) was proven to have no significance because it had a predictive value similar to that of the serum levels of esRAGE (Z = 0.993, p = 0.351) or sRAGE (Z = 1.116, p = 0.265) alone. Subsequently, Model D (sRAGE + esRAGE + ELWI) showed the best 28-day mortality predictive value with a cut-off value of 0.426 (AUC 0.841; p < 0.001), and Model A (sRAGE + ELWI) had a cut-off value of 0.401 (AUC 0.820; p < 0.001), followed by sRAGE (AUC 0.704, p = 0.004), esRAGE (AUC 0.717, p = 0.002), and ELWI (AUC 0.637, p = 0.028). In addition, there was no statistically significant difference between Model A and Model D (Z = 0.966, p = 0.334). The admission level of sRAGE was higher in the nonsurvival group, while the serum esRAGE level showed the opposite trend. Model A and Model D could be used as reliable combined prediction models for predicting the 28-day mortality of ARDS patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which is characterized by acute hypoxemia, respiratory distress, and pulmonary exudative lesions, is a highly heterogeneous and complicated critical illness secondary to pneumonia, sepsis, trauma, or blood transfusion1. Globally, ARDS accounts for 10% of intensive care unit admissions and approximately 35–46% of hospital mortality2. Survivors of ARDS typically suffer long-term sequelae, including physical, cognitive, and psychological diseases, and the 3-month long-term mortality ranges from 38 to 41.2%3, bringing a great economic burden to families and society. With the lack of effective drug interventions, the accurate judgement of disease status and effective clinical management are critically important for patients with ARDS.

Currently, there are several scoring systems for the early identification of patients at risk of developing ARDS and the prediction of outcomes in ARDS patients, including the oxygenation ratio PaO2/FiO2, extravascular lung water index (ELWI), Murray lung injury score (MLIS), and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE II)4,5,6,7. Despite traditionally being considered purely prognostic indicators, both the oxygenation ratio and the oxygenation index had low sensitivity and specificity in the early diagnosis and lagged behind the actual progression of ARDS8. ELWI, as a complementary nonspecific index, was employed for the diagnosis of pulmonary oedema and to predict the progression of acute lung injury. However, pulmonary oedema can develop in multiple diseases, including neurogenic pulmonary oedema and high-altitude pulmonary oedema, in addition to ARDS5,9,10. All types of scoring systems, such as the Murray lung injury score and APACHE II, were very useful to predict the risk of mortality and to grade the severity of disease; however, these systems also led to some discrepancies in judgement because of the subjective assessment. Hence, it is of paramount importance to find biological diagnostic indicators with high specificity and sensitivity to solve this conundrum.

The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a cell-surface multiligand member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that carries out multiple biological functions in many disease models, such as diabetic complications, decreased renal function, atherosclerosis, and metabolic syndrome11,12. A growing number of studies have revealed that elevated plasma levels of cell surface RAGE (sRAGE) have been detected in an animal lung injury model when measured at baseline, which may reflect the severity of lung epithelial injury13,14. RAGE inhibition or RAGE gene knockout was found to significantly attenuate pulmonary capillary permeability and reduce inflammatory reactions in lung ischaemia‒reperfusion injury model mice15. Moreover, sRAGE could be considered a quantitative reflective index for alveolar epithelial and endothelial damage induced by the systemic inflammatory response in patients with acute lung injury (ALI)16. Despite the possible correlation between sRAGE and lung injury-related diseases, relevant clinical study data are still inadequate in patients with ARDS. On the other hand, in contrast to sRAGE, endogenous secretory RAGE (esRAGE) is a truncated form cleaved from sRAGE that lacks the transmembrane and cytoplasmic portions of the receptor17,18. esRAGE can prevent cell-bound sRAGE signalling from binding to its associated ligands by competitive inhibition, serving as a decoy that abolishes cell activation18,19. Although many studies have been performed regarding the effects of esRAGE levels on morbidity in associated conditions, including diabetes and preeclampsia, there are few reports regarding the correlation between esRAGE and ARDS in the literature.

In this prospective study, we aimed to evaluate the value of serum sRAGE and esRAGE as biomarkers reflecting disease prognosis and search for a practical prediction model in critically ill patients with ARDS.

Materials and methods

Trial registration and ethics

We confirm that the present study was performed according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This prospective study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University (No: 2020KY026) and registered at www.chictr.org.cn (number: ChiCTR2100041618). Informed consent was obtained from patients or the nearest relative prior to the study.

Setting and patients

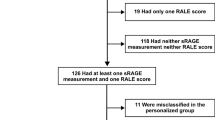

In this prospective cohort study, 120 ARDS patients were recruited from the intensive care unit (ICU) of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University from January 2021 to June 2022. Finally, a total of 83 patients with ARDS were enrolled in the study and further divided into a survival group and a nonsurvival group according to the patients’ outcomes (Fig. 1). All patients with ARDS were diagnosed according to the Berlin definition20, and the treatment followed the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute lung injury/ARDS in the Society of Critical Care Medicine, Chinese Medical Association.

The exclusion criteria of all the patients mentioned above were as follows: (1) pregnancy, (2) age < 18 years old, (3) terminal-stage nephropathy patients undergoing blood purification therapy, (4) patients with acute complications of diabetes, (5) Alzheimer’s disease, (6) amyloidosis or progression of solid tumours, and (7) readmission to the ICU.

Clinical data collection

Demographic data, including age, sex, temperature, heart rate and mean arterial pressure, were recorded when the patients were admitted to the ICU. Subsequently, all patients were subjected to continuous ECG monitoring, and then the PiCCO (pulse indicator continuous cardiac output) catheter was inserted into the femoral artery, which was used for the measurement of cardiac parameters and pulmonary oedema, such as PVPI (pulmonary vascular permeability index) and ELWI, which could be quantitatively measured through the transpulmonary thermodilution (TPTD) technique. PVPI reflected the alveolar-capillary permeability, and ELWI was used as an index of lung water content and oedema.

Next, all patients underwent standard laboratory investigations and imaging tests that included complete blood counts; blood electrolyte measurements; liver and renal function tests; analysis of electrolytes, blood gases and pH; a chest X-ray; and a CT examination.

For ventilated patients, pulmonary gas exchange and ventilatory parameters, including FiO2 (inspiratory fraction of oxygen), PaO2 (arterial partial pressure of oxygen), pulmonary compliance, Ppeak (peak inspiratory pressure), PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure) and so on, were measured when such patients were admitted to the ICU.

In addition, the clinical parameters were assessed for each patient on admission to the ICU, which mainly involved SOFA scores, APACHE II scores, MLIS scores, and severity of ARDS according to the Berlin definition. The patients were assessed and classified into three severity levels of ARDS according to the Berlin definition. The SOFA (sequential organ failure assessment) score was developed as a tool to quantitatively describe the time course of organ dysfunction21. The APACHE II (acute physiology and chronic health evaluation) score is a widely used method to describe the disease severity of patients in the ICU22. The MLIS (Murray Lung injury score) was also used to describe the disease severity of ARDS23. The main clinical outcome measure was 28-day mortality.

Sample collection and biomarker measurements

Blood samples were obtained within 6 h of admission to the ICU. The plasma was separated and then stored at − 80 °C until further processing. Previously collected and frozen serum samples were used to determine the levels of sRAGE (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and esRAGE (B-Bridge International, Sunnyvale, CA) by a commercial sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. During the ELISAs, all measurements were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sample size

Multivariable analyses, such as multiple regression, logistic regression, and factor analysis show interdependence. No exact predictions are truly feasible. Consequently, rules of thumb are often adopted that the sample size should be 5, 10, or 20 times the number of variables24. Based on the abovementioned factors, we found 8 variables, and the sample size of surviving and nonsurviving patients was defined as 80 patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 and MedCalc 20.0. Normally distributed continuous data were analysed through Student’s t test and are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Nonnormally distributed continuous data were analysed through the Mann‒Whitney U test and are presented herein as the median (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages) and were analysed using a chi-square (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the clinical parameters for survival status in ARDS patients. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to verify the accuracy of the prognosis of the related parameters. The accuracy of prognosis was determined using the area under the ROC curve (AUC; 95% confidence interval (CI) and p value < 0.05). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

The association between clinical parameters and survival status in ARDS patients

A total of 120 patients with ARDS were recruited, 83 of whom were divided into two groups, a survivor group and a nonsurvivor group, based on 28-day mortality. The clinical characteristics of the study population were recorded.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in the general clinical characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index, and basic vital signs (Table 1; all p > 0.05). There were also no significant differences between the two groups in the primary diagnosis, including trauma, pneumonia, sepsis, cardiovascular disease, pancreatitis, and others (Table 1; all p > 0.05). Moreover, there were no significant differences between the two groups in pulmonary compliance, pulmonary vascular permeability index (PVPI), or the parameters of mechanical ventilation, including Ppeak, Ppalt, PEEP, FiO2, PaO2/FiO2, and tidal volume (Table 1; all p > 0.05).

However, the survivors had a significantly lower Murray lung injury score and APACHE II and SOFA II scores (Table 1; all p < 0.05). The nonsurvivors had a significantly higher ELWI (p = 0.040), a prolonged length of stay in the ICU (p = 0.032), and a longer duration of mechanical ventilation (p = 0.021). According to the Berlin definition, 3 patients were classified as mild ARDS, and 12 and 24 were classified as moderate or severe ARDS, respectively. The survival was significantly higher in mild ARDS than in moderate or severe ARDS (p = 0.033) (Table 1).

The serum level of esRAGE was significantly higher in the survivor group than in the nonsurvivor group (p < 0.05), and the serum level of sRAGE was significantly higher in the nonsurvivor group (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Univariate and multivariate regression analyses of the clinical parameters for survival status in ARDS patients

Despite substantial differences in some clinical parameters between the survivors and nonsurvivors, it is unclear whether these differences are of clinical significance. To determine the potential prognostic factors of survival in ARDS patients, further univariate and multivariate regression analyses, which included the 9 variables relevant to the prognosis of disease progression mentioned above, were performed. Univariate analysis showed that serum levels of sRAGE and esRAGE, ELWI, MLIS, APACHE II score, severity of ARDS, and length of stay in the ICU were closely associated with ARDS (Table 2, univariate analysis). However, multivariable logistic regression analysis indicated that only the serum levels of sRAGE and esRAGE and ELWI were significant factors for prognosis in ARDS (Table 2, multivariate regression analysis).

The related parameters predicting 28-day mortality in ARDS patients

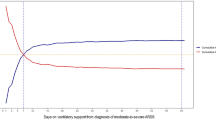

To determine the independent predictors of 28-day mortality, we assessed the predictive validity of ELWI and the serum levels of sRAGE and esRAGE by receiver operator curves (ROC). ELWI and the serum levels of sRAGE and esRAGE were independent predictors of mortality, with AUC values of 0.637, 0.704, and 0.717, respectively (Table 3; Fig. 2A; all p < 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in the AUC among the three indicators (Table 4; all p > 0.05).

Construction of the prognosis prediction model based on the pairwise combination strategy among ELWI, sRAGE, and esRAGE

Subsequently, we performed a pairwise combination strategy among ELWI, sRAGE, and esRAGE to predict 28-day mortality in ARDS patients. To determine the feasibility of the prediction model, the probability values of ELWI, sRAGE and esRAGE in different models were assessed by logistic regression analysis. In contrast with Model A (sRAGE + ELWI), Model C (sRAGE + esRAGE), and Model D (sRAGE + esRAGE + ELWI), Model B (esRAGE + ELWI) could not be developed into a valid linear regression model because the coefficient of ELWI did not show statistical significance (Table 5; p > 0.05), suggesting that Model B cannot be exploited to predict the 28-day mortality in ARDS patients (Table 5).

According to Youden’s index25, the cut-off values of Model A and Model D were 0.401 (AUC 0.820, sensitivity 76.9%, specificity 75.0%) and 0.426 (AUC 0.841, sensitivity 79.5%, specificity 75.0%), respectively, in predicting the 28-day mortality of ARDS (Table 6). The predictive value of Model A or Model D was slightly better than that of ELWI, sRAGE level, or esRAGE level alone (Tables 6 and 7, Fig. 2B,D).

At a cut-off value of 0.495, the AUC of Model C was 0.757, with a sensitivity of 66.7% and a specificity of 81.8% (Table 6). The AUC of Model C was higher than that of the sRAGE level or esRAGE level alone, but with no statistically significant difference (Tables 6 and 7 and Fig. 2C), suggesting that Model C had a predictive value similar to that of the serum levels of sRAGE and esRAGE alone, which does not have an advantage in predicting 28-day mortality compared with Model A and Model D.

Meanwhile, there was no statistically significant difference in AUC between Model A and Model D (Table 7 and Fig. 2E). The above data indicate that Model A and Model D were more powerful in predicting the outcome of ARDS than the related parameters alone.

Discussion

In this study, two biomarkers (namely, sRAGE and esRAGE) were measured in the blood to explain the associated clinical features of ARDS. The expression of esRAGE increased persistently in survivors of ARDS, and the serum sRAGE level increased persistently in nonsurvivors of ARDS. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that sRAGE/esRAGE levels and ELWI were independent risk factors for the prognosis of ARDS. Moreover, the sRAGE/esRAGE levels and ELWI alone also had a favourable predictive capability for 28-day mortality in patients with ARDS. Youden’s index analysis showed that Model A (sRAGE + ELWI) and Model D (sRAGE + esRAGE + ELWI) had a better predictive power for the prognosis of ARDS than the related parameters alone.

ARDS is a diffuse uncontrolled alveolar inflammatory disease, the hallmarks of which are alveolar damage, lung microvascular leakage, and overt noncardiogenic pulmonary oedema1,26. The inflammatory response plays an important role in the progression of ARDS, and it involves the infiltration of various immune cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes, into the lung tissues and small airways26. RAGE, as a multiligand receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily, is able to induce intracellular signalling pathways that regulate several inflammatory diseases by binding a diverse array of ligands, such as advanced glycation end products (AGEs), S100/calgranulins, HMGB1 proteins, amyloid-β peptides and the family of β-sheet fibrils27. For instance, inhibition of the HMGB1/RAGE axis by RAGE knockout reduced the activity of microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in a mouse model of stress-induced hypertension28. In limb ischaemia and reperfusion models, the inhibition of RAGE binding with HMGB1 by FPS-ZM1 significantly decreased the release of HIF-1a, NLRP3, Caspase-1, TNF-a, and IL-6 expression to mediate the inflammatory response29. Although serum sRAGE/esRAGE levels have been demonstrated to be involved in multiple inflammatory diseases, it is still unknown whether they participate in the ARDS-induced inflammatory response. This was the first study to evaluate sRAGE/esRAGE expression and its prognostic value in patients with ARDS, and we found that the plasma sRAGE level was significantly higher in the ARDS group than in the non-ARDS group, but the plasma esRAGE level was significantly lower in the ARDS group, indicating a positive correlation between the severity of ARDS and sRAGE expression, which may be reversed by esRAGE. The most reasonable explanation was probably that esRAGE, as a competitive inhibitor, bound with the same ligands and precluded cell-bound RAGE signalling, which attenuated the inflammatory-immune response. Therefore, the expression of serum esRAGE had organ-protecting and anti-inflammatory effects, and this finding has also been confirmed in the literature. For instance, the maternal serum esRAGE concentration and esRAGE/sRAGE ratio were significantly higher in patients with preeclampsia than in healthy pregnant controls30. The upregulation of esRAGE might also be part of the cell's antioxidative defences against plaque formation as a result of oxidative stress in the T2DM phenotype31. With the above consideration, we speculated that sRAGE expression increased as the disease worsened and that esRAGE expression increased as the disease improved, which was helpful for the early assessment of the prognosis in ARDS and might become an objective marker. In addition, multivariate analysis retained serum sRAGE/esRAGE levels as independent predictors of 28-day mortality in the ARDS patients in this study.

Numerous potential prognostic factors were associated with survival in patients with ARDS. Extravascular lung water (EVLW) is the generic name for the fluid within the lung but outside the vasculature, including extravasated plasma and intracellular water, which could be induced by elevated osmotic pressure and pulmonary vascular permeability. Kor et al.32 demonstrated that ELWI was a predictive marker for distinguishing ARDS-induced postoperative pulmonary oedema from cardiogenic pulmonary oedema, ultimately leading to impaired oxygenation and lung compliance. In our study, not only ELWI but also sRAGE and esRAGE had a close correlation with mortality in patients with ARDS by multivariate analysis. Furthermore, according to the statistically significant differences, ELWI, sRAGE, and esRAGE were chosen as independent predictors to establish the prediction model of 28-day mortality in ARDS patients.

Both scoring systems and real-time monitoring systems are highly sensitive but lack specificity for the progression of the disease. The biological indicators, although lacking sensitivity, had the advantage of being highly specific with the temporal requirements for protein synthesis. Theoretically, compared with any parameter alone, the pairwise combination strategy among ELWI, sRAGE, and esRAGE could significantly increase the sensitivity and specificity of predictive ability for 28-day mortality in ARDS patients. Nevertheless, Li et al.33 examined whether changes in the level of serum fibroblast growth Factor 21 (FGF21) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores could predict the 28-day mortality of ICU patients with sepsis and ARDS, and no significant difference was observed between the FGF21 and SOFA scores. Therefore, these clinical indicators had considerable variability in predicting the disease status. Similarly, our data analysis revealed that no statistically significant changes were found in predicting the mortality of ARDS in analyses of ELWI versus sRAGE, ELWI versus esRAGE, or sRAGE versus esRAGE, suggesting that ELWI, sRAGE, and esRAGE possessed a similar predictive value for disease progression in patients with ARDS.

Nevertheless, there were also relatively large heterogeneities in ELWI, sRAGE, and esRAGE, which might cause offsets and increase the risk of misjudgement in disease prediction. Thus, the combined forecasting model was established to improve the predictive power34. Interestingly, except for Model A and Model D, other combinations failed to increase the AUC for the prediction of mortality in ARDS. These negative results might be explained by the limited samples and medical intervention before ICU admission, which could bias the evaluation results. Nevertheless, we could still conclude that ELWI, sRAGE, and esRAGE were predictors of mortality in ARDS, and the combination of sRAGE and ELWI was able to increase the power of predicting the prognosis of ARDS. To date, the relationship between esRAGE level and the mortality of ARDS has not been reported elsewhere in the literature.

Moreover, the plasma sRAGE/esRAGE levels and ELWI, based on the statistical analysis results, may be used to assess prognosis in patients with ARDS alone. With the popularization of the invasive monitoring technique PiCCO, ELWI has the advantage of low cost and easy acquisition. However, during the data collection by the thermodilution technique, the accuracy of ELWI is affected by the skill level of the operator35,36, which indicates that ELWI is not a pure objective indicator. In contrast to ELWI, the plasma sRAGE/esRAGE level measurement has the potential to be an objective prognostic tool because it is an easy, objective, economical approach with minimal tissue trauma. In addition, Model A (sRAGE + ELWI) and Model D (sRAGE + esRAGE + ELWI) showed stronger predictive power than ELWI, sRAGE and esRAGE alone. From the data analysis perspective, Model A did not have a statistically superior predictive advantage over Model D. However, according to the reasonable allocation of medical resources and optimal socioeconomic benefits, Model A (sRAGE + ELWI) may serve as the preferred regimen for predicting the prognosis of ARDS.

Although strict inclusion and exclusion criteria were used, the present study still had several limitations: (1) this was a single-centre study, and the sample size was limited. An expanded sample size is needed in future studies. (2) The timing of the sample collection was limited, and the lack of dynamic inspection might also be partly attributable to detection bias. In addition, we failed to observe changes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) biomarkers, which might induce an underestimation of the value of these biomarkers. (3) Owing to the relatively small volume of blood collected and limited funds, it was impossible to detect and research all biomarkers for ARDS (such as biomarkers related to epithelial injury, endothelial injury, and other inflammatory factors). (4) The number of cases with mild ARDS was relatively small. In this regard, the assessment of mild ARDS might be biased to a certain extent. Accordingly, the generalization of our results to other ARDS patients requires some caution.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that the admission level of sRAGE was higher in nonsurviving ARDS patients, while the serum esRAGE level showed the opposite trend, and the use of the plasma sRAGE/esRAGE levels was helpful for the assessment of the prognosis in ARDS and might be an objective marker. Model A (sRAGE + ELWI) and Model D (sRAGE + esRAGE + ELWI) had stronger predictive power for predicting the 28-day mortality of ARDS. Our results are conducive to the early distinction of critical ARDS patients and the early intervention and management of ARDS.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- RAGE:

-

Receptor for advanced glycation end products

- sRAGE:

-

Elevated plasma levels of cell surface RAGE

- esRAGE:

-

Endogenous secretory RAGE

- ELWI:

-

Extravascular lung water index

- SOFA:

-

Sequential organ failure assessment

- APACHE II:

-

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

- MLIS:

-

Murray lung injury score

- PiCCO:

-

Pulse indicator continuous cardiac output

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

References

Diamond, M., Peniston, H. L., Sanghavi, D., & Mahapatra, S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. In StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) (2022).

Matthay, M. A. et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 5, 18 (2019).

Rezoagli, E., Fumagalli, R. & Bellani, G. Definition and epidemiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Transl. Med. 5, 282 (2017).

Lai, C. C. et al. The ratio of partial pressure arterial oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen 1 day after acute respiratory distress syndrome onset can predict the outcomes of involving patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e3333 (2016).

Jozwiak, M., Teboul, J. L. & Monnet, X. Extravascular lung water in critical care: Recent advances and clinical applications. Ann. Intensive Care 5, 38 (2015).

D’Negri, C. E. & De Vito, E. L. Making it possible to measure knowledge, experience and intuition in diagnosing lung injury severity: A fuzzy logic vision based on the Murray score. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 10, 70 (2010).

Sun, W. et al. A combination of the APACHE II score, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, and expired tidal volume could predict non-invasive ventilation failure in pneumonia-induced mild to moderate acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Ann. Transl. Med. 10, 407 (2022).

Karbing, D. S. et al. Variation in the PaO2/FiO2 ratio with FiO2: Mathematical and experimental description, and clinical relevance. Crit. Care 11, R118 (2007).

Lo-Cao, E., Hall, S., Parsell, R., Dandie, G. & Fahlstrom, A. Neurogenic pulmonary edema. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 45, 678e673-678e675 (2021).

Sydykov, A. et al. Pulmonary hypertension in acute and chronic high altitude maladaptation disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1692 (2021).

Alexiou, P., Chatzopoulou, M., Pegklidou, K. & Demopoulos, V. J. RAGE: A multi-ligand receptor unveiling novel insights in health and disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 17, 2232–2252 (2010).

Kalea, A. Z., Schmidt, A. M. & Hudson, B. I. Alternative splicing of RAGE: Roles in biology and disease. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 16, 2756–2770 (2011).

Negrin, L. L., Ristl, R., Halat, G., Heinz, T. & Hajdu, S. The impact of polytrauma on sRAGE levels: Evidence and statistical analysis of temporal variations. World J. Emerg. Surg. 14, 13 (2019).

Su, X., Looney, M. R., Gupta, N. & Matthay, M. A. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) is an indicator of direct lung injury in models of experimental lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 297, L1-5 (2009).

Sternberg, D. I. et al. Blockade of receptor for advanced glycation end product attenuates pulmonary reperfusion injury in mice. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 136, 1576–1585 (2008).

Jabaudon, M. et al. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products predicts impaired alveolar fluid clearance in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 192, 191–199 (2015).

Yonekura, H. et al. Novel splice variants of the receptor for advanced glycation end-products expressed in human vascular endothelial cells and pericytes, and their putative roles in diabetes-induced vascular injury. Biochem. J. 370, 1097–1109 (2003).

Raucci, A. et al. A soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound form by the sheddase a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10). FASEB J. 22, 3716–3727 (2008).

Geroldi, D., Falcone, C. & Emanuele, E. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products: From disease marker to potential therapeutic target. Curr. Med. Chem. 13, 1971–1978 (2006).

Force, A. D. T. et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin definition. JAMA 307, 2526–2533 (2012).

Vincent, J. L. et al. The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working group on sepsis-related problems of the European society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 22, 707–710 (1996).

Knaus, W. A., Draper, E. A., Wagner, D. P. & Zimmerman, J. E. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med. 13, 818–829 (1985).

Murray, J. F., Matthay, M. A., Luce, J. M. & Flick, M. R. An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 138, 720–723 (1988).

Norman, G., Monteiro, S. & Salama, S. Sample size calculations: Should the emperor’s clothes be off the peg or made to measure?. BMJ 345, e5278 (2012).

Yin, J., Mutiso, F. & Tian, L. Joint hypothesis testing of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve and the Youden index. Pharm. Stat. 20, 657–674 (2021).

Virani, A. et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome definition, causes, and pathophysiology. Crit. Care Nurs. Q 42, 344–348 (2019).

Palanissami, G. & Paul, S. F. D. RAGE and its ligands: Molecular interplay between glycation, inflammation, and hallmarks of cancer-a review. Horm. Cancer 9, 295–325 (2018).

Zhang, S. et al. HMGB1/RAGE axis mediates stress-induced RVLM neuroinflammation in mice via impairing mitophagy flux in microglia. J. Neuroinflammation 17, 15 (2020).

Mi, L. et al. HMGB1/RAGE pro-inflammatory axis promotes vascular endothelial cell apoptosis in limb ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 116, 109005 (2019).

Kwon, J. H., Kim, Y. H., Kwon, J. Y. & Park, Y. W. Clinical significance of serum sRAGE and esRAGE in women with normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. J. Perinat. Med. 39, 507–513 (2011).

Piarulli, F. et al. Role of endogenous secretory RAGE (esRAGE) in defending against plaque formation induced by oxidative stress in type 2 diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis 226, 252–257 (2013).

Kor, D. J. et al. Extravascular lung water and pulmonary vascular permeability index as markers predictive of postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome: A prospective cohort investigation. Crit. Care Med. 43, 665–673 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Does an increase in serum FGF21 level predict 28-day mortality of critical patients with sepsis and ARDS?. Respir. Res. 22, 182 (2021).

Subudhi, S. et al. Strategies to minimize heterogeneity and optimize clinical trials in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): Insights from mathematical modelling. EBioMedicine 75, 103809 (2022).

Wolf, S. et al. How to perform indexing of extravascular lung water: A validation study. Crit. Care Med. 41, 990–998 (2013).

Litton, E. & Morgan, M. The PiCCO monitor: A review. Anaesth Intensive Care 40, 393–409 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the intensive care unit staff of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University and the colleagues at this institute for their support and help.

Funding

This study was supported by the Guiding Project of Science and Technology in Nantong City, Jiangsu Province (JCZ18078), and the Special Project of Clinical Medicine at Nantong University (2019LY003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.Z, D.K.Y, L.P.W, and W.L.G designed the study. C.L.Z, X.Z, W.S.Z, Z.H.X and W.L.G acquired the data. C.L.Z, L.P.W, and W.L.G analysed the data. D.K.Y, and C.L.Z wrote the manuscript and prepared figures and tables. L.P.W and W.L.G revised the manuscript and modified the language. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Yin, D., Zhu, X. et al. Predictive value of ELWI combined with sRAGE/esRAGE levels in the prognosis of critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Sci Rep 13, 15463 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42798-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42798-4