Abstract

An extended (3+1)-dimensional Kadomtsev–Petviashvili–Boussinesq equation is studied in this paper to construct periodic solution, n-soliton solution and folded localized excitation. Firstly, with the help of the Hirota’s bilinear method and ansatz, some periodic solutions have been derived. Secondly, taking Burgers equation as an auxiliary function, we have obtained n-soliton solution and n-shock wave. Lastly, we present a new variable separation method for (3+1)-dimensional and higher dimensional models, and use it to derive localized excitation solutions. To be specific, we have constructed various novel structures and discussed the interaction dynamics of folded solitary waves. Compared with the other methods, the variable separation solutions obtained in this paper not only directly give the analytical form of the solution u instead of its potential \(u_y\), but also provide us a straightforward approach to construct localized excitation for higher order dimensional nonlinear partial differential equation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The history of the study of nonlinear evolution equations(NEEs) is sporadic during the past decades. In spit of the fact that physical phenomena have been carried out by the solutions of fundamental nonlinear models, there are a small group of methods can be devised to derive them. NEEs that display wave phenomena can be basically sorted out as dispersive and hyperbolic. The theory of hyperbolic partial differential equation is well formulated, whereas the theory of dispersive wave equation is not, such as the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, sine-Gordon equation, KdV equation as well as the mKdV equation. The application of the NEEs which got the most notice is in fluid dynamic. Lately, the application of the NEEs in other fields, such as water wave, quantum mechanic, crystal optic, lattice dynamic, nerve pulse propagation, active transmission line and various areas of continuum mechanic, are getting more attention and there is an urgent demand for more universal method. Therefore, to derive the analytical solution of NEEs, numerous helping methods have been put forth, such as inverse scattering transform1, Darboux transform2, Lax pair3, Lie group4, Hirota bilinear form5 as well as Bäcklund transform6. Theoretical progress of these nonlinear models depends mainly on how fast one can produce approximate and numerical solution which is sample as much of the corresponding parameter space. In most cases, numerical solution is a poor mean of sampling parameter space to extract the solution and the accuracy of the approximate solution relies on the value of the parameter, large or small. Apart from linearization, other result mainly obtained from the perturbation method.

Rogue wave7 has received considerable attentions in recent years. Oceanographers refer to it as a type of isolated, Gaussian-distributed event that occurs in the ocean more frequently than usual. “New Year Wave”8, which was discovered in the North Sea on January 1, 1995, is the most well-known rogue wave. The optical rogue wave was first detected through an experiment in 20079 and the ”Peregrine” soliton in 201010. In nature, rogue waves are common and can be found in a variety of settings, including doped fibers11,12, acoustic turbulence13, microwave transport14, nonlinear optical cavities15 and finance16. The usual property characterizing the rogue wave in different contents is the observance of great deviation of the wave height from Gaussian statistic, along with the probability density function which results in frequent emission of the giant wave. In spite of the distinctiveness of each experiment, other features can also be identified as the existence of the activity of uncorrected “grain”, which distributes in larger spatial domain unevenly. Based on the nature of the wave, grain may stem from different origins, such as the soliton in nonlinear system, packet in linear propagating wave, wave clustering in spatial domain. All of these can occur under different dynamics, as a spatial symmetry breaking, a hypercycle amplification17, a temporal delay or a transport phenomenon. On the other hand, it has been proved that rogue wave can be generated in the microwave experiment without the nonlinearity18. This implies that the nonlinearity plays the part of inducing soliton-like structure. In order to verify this hypothesis, the researchers conduct a linear optical experiment and compare the result with those from a nonlinear cavity19. The outcome indicates the rogue wave relates to the appearance of a suitable amount of inhomogeneity and granularity, independently if they are induced by a linear or nonlinear system.

In real life, most of the waves interact with others. During the interactions , plenty of localized excitation phenomena will arise. The soliton is the most basic excitation of the (1+1)-dimensional nonlinear model, such as peakon, breather, compacton, instanton, kink soliton and bell soliton. In general, there are several “variable separation” methods used to construct folded(multi-valued) waves. The first method is the “formal variable separation approach” (FVSA)20; The second method is to find derivative-dependent function separation solution21 through conditional symmetry; The third one is the so-called “multi-linear variable separation approach” (MLVSA)22. Except for that, ETM23 and projective Riccati equation method(PREM)24 are also effective in dong that. One common ground among these methods is the existence of free functions. The existence of arbitrary functions render various localized excitations, and the richness of localized excitations plays an essential role in exploring the corresponding dynamical properties of nonlinear models. Dai25 has derived exponential variable separation solution for the (2+1)-dimensional KdV equation by the two function approach and discussed the inelastic interactions between foldon and semi-foldon under suitable function selection. Besides, Dai26 has derived ten different variable separation solutions for the (2+1)-dimensional Bogoyavlenskii–Schiff model through the generalized Riccati equation mapping and improved projective Riccati equation method that link independent functions. In27, Huang analyzed three types of localized excitations: multi-lump, multi-dromion, periodic solution in terms of Hirota’s bilinear method and variable separation approach for an extended Jimbo-Miwa equation. Other (2+1)-dimensional models, for instance, asymmetric NNV equation, the Nizhnik-Novikov-Veselov system, asymmetric DS equation, a general (M+N)-component Ablowitz–Kaup–Newell–Segur system, dispersive long wave equation, Maccari system, Broer–Kaup–Kupershmidt system, long wave–short wave interaction model are considered by Lou28,29,30 and an usual expression with arbitrary functions are established. For more details about variable separation method, the readers can refer to31,32,33.

Until now, the attention is mainly focus on (2+1)-dimensional models while (3+1)-dimensional cases are rarely considered. Beyond that, the localized excitations obtained via the MLVSA needs rigorous prerequisite conditions. Taking (2+1)-dimensional case as an example

One has to convert (Eq. 1) into bilinear form at first, via the transformation \(u=c_0(\ln f)_x+u_0\) or \(u=c_0(\ln f)_{xx}+u_0\), where \(c_0\) is a constant and \(u_0\) is a function relating to x, y, t which will be determined later. Through long and tedious calculation, its potential \(u_y\) usually has the form

or

where \(c_0,a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4\) are constants and \(u_0\) might be the function with respect to x, t. If \(u_0\) is truly a function only relates to x and t, the potential \(u_y\) will win its freedom via the choosing of F, G. Briefly speaking, F[x] and G[y, t] can be defined to be any functions. However, the above conditions are too rigorous. Particularly, one has to use \(u_y\) to simulate u and this may cover the true face for what u really is. Here, we are stroke by some interesting ideas: Can we relax the constraints? Can we derive variable separation solution in a more simple way? To answer above question, we present a new variable separation solution for (3+1)-dimensional case, i.e.

where \(\lambda _i(i=1,...,4)\) are constants to be determined later, \(\digamma _1[x],\digamma _2[y],\digamma _3[z],\digamma _4[t]\) are free functions.

Next, via the ansatz and variable separation function (2), we are going to study a new (3+1)-dimensional generalized KP-Boussinesq equation

where \(u=u(x,y,z,t)\) is differentiable function in terms of temporal variable t and spatial variables x, y, z; \(u_{xz}\) is an extra item added to KP-Boussinesq equation34.

Our treatment goes as follows. In “Painlevé analysis” , we have transferred Eq. (3) into bilinear form through the logarithmic transformation. Then, with the help of the ansatz that consists of exponential and trigonometric function, periodic solutions have been obtained under specific condition. Moreover, we have plotted three typical periodic solutions in 2D and 3D. In “Periodic solution of (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq equation” , taking Burgers equation as an auxiliary function, we have derived n-soliton as well as n-shock wave for Eq. (3). The mechanism of the shock wave have been studied systemically. In “Multi-soliton and shock wave of (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq equation” , we have used the variable separation function (2) to construct folded solitary waves of Eq. (3) to verify its efficiency. Besides, we have discussed the interaction behaviours and superimposed structures of folded solitary waves. Therefore, lots of new structures have been obtained. To our knowledge, these solutions have not been reported elsewhere. “Variable separation solution of (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq equation” contains a summary. The variable separation solutions obtained here not only present the analytical form of solution u instead of its potential \(u_y\), but also provide us a distinct way to construct localized excitation for higher order dimensional nonlinear partial differential equation. Therefore, we believe the method proposed in current work will be helpful in finding localized excitation solution for other nonlinear systems.

Painlevé analysis

The integrability of some reductions to ordinary differential equations and the inverse scattering transform integrability of the soliton equation are fundamentally related, as shown by the Painlev’e property. If all of the movable singularity maifolds’ solutions are single-valued, the PDE is said to have passed the Painlev’e test. Under this sense, we follow the same manners of WTC-Kruskal algorithm in35. Assuming the solution of Eq. (3) can be expressed as Laurent series

Substitution into Eq. (3) and balancing the most dominant terms, one has

Substituting Eqs. (5), (4) into Eq. (3) yields

and a characteristic equation with one branch for resonances at \(r=-1,1,4\) and 6. Applying the Kruskal’s gauge to \(\phi (x,y,z,t)=x-\psi \), one has

where \(u_1,u_4\) is free and \(\psi =\psi (x,y,z,t)\). The compatibility condition does not hold at resonance \(j=6\) is

Briefly speaking, Eq. (3) does not pass Painlevé test, which means it is not integrable in Painlevé sense.

Periodic solution of (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq equation

In this part, we will derive periodic solution for Eq. (3) with the help of Hirota’s bilinear method. Under the transformation \(u=(\ln \phi )_{x}\), Eq. (3) becomes

where D is bilinear operator and it is defined by

A straightforward computation indicates (Eq. 6) has the following form

Assuming \(\phi \) can be written as

where \(\chi _i=p_ix+k_iy+\omega _it+l_iz(i=1,2,3,4).\) Based on anstaz (Eq. 8), diverse exact solutions can be constructed. Here, we only consider four typical cases under the condition of \(p_1=p_3=p_4=k_2=0\). Substituting Eq. (8) into Eq. (7) and zeroing all the coefficients of \(e,\sin ,\cos \), we have

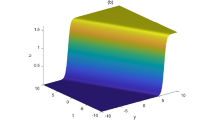

Substituting (9)–(12) and \(\chi _i=p_ix+k_iy+\omega _it+l_iz\) back to \(u=(\ln \phi )_{x}\), we can derive periodic solutions for Eq. (3). Here, by choosing appropriate parameters, we have plotted three typical periodic solutions in Fig. 1, under conditions (9) and (10). As we can see, the first periodic solution is periodic along x-axis, while the third one is periodic in each direction(both x- and t-axis). As regards the middle one, based on Fig. 1e, the period decreases while the amplitude tends to become greater along t-axis.

Three typical periodic solutions of Eq. (8) with \(y=z=0\), (a,d) condition (2.3) under \(\delta _1=\delta _4=2,\delta _2=\delta _3=1,\omega _1=2,\omega _2=3,\omega _3=1/2,k_1=k_4=1,k_3=2,p_2=3,\) (b,e) condition (2.3) under \(\delta _1=1/2,\delta _2=\delta _3=1,\delta _4=2,\omega _2=1,k_1=1,k_3=k_4=2,p_2=1,\) (c,f) condition (10) under \(\delta _1=1/2,\delta _2=\delta _3=1,\delta _4=2,\omega _2=1,k_1=1,k_3=k_4=2,p_2=1\).

Multi-soliton and shock wave of (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq equation

Starting with Burgers equation

Setting \(\mu =\mathcal {T}(\mathcal {\gamma })\), \(\gamma =px+ky+lz-\omega t\), Eq. (13) turns to

with the multi-soliton solution36

where \(x_{j,0}\) is constant, \(\omega _j=-k^2_j.\) Back to Eq. (3) with the transformation \(u(x,y,z,t)=\mathcal {R}(\gamma )\), we have

Balancing the highest order nonlinear term and partial term, we have

where \(\mathcal {J}_0,\mathcal {J}_1\) are constants. Substituting Eqs. (17) and (14) into Eq. (16) results an algebraic system

Solving above system, we have

Therefore, the n-soliton solution of Eq. (3) reads

with the constraint \(p_j^3-\omega _j \ne 0,p_j\ne 0.\)

To construct multi-soliton solutions to nonlinear evolution equations, Hirota developed a new “direct method” in 19715. The goal was to transform existing variables into new ones so that multi-soliton solutions would display particularly straightforwardly. The equations were found to be quadratic for the new dependent variables, and all derivatives showed up as Hirota’s bilinear derivatives (hence the name “Hirota bilinear form”). Although inspired by the inverse scattering transform (IST), the Hirota’s direct method does not need strong, sophisticated assumptions like the IST and applies to a wider range of equations than the IST. All of which makes Hirota’s direct method the optimal tool to understand soliton scattering for further development of soliton theory. The multi-soliton solutions obtained by the Hirota’s direct method through the Hirota bilinear form, also known as n-soliton solution, has the form

where the first \(\sum \) means a summation over all possible combinations of \(\mu _i=0,1\)(\(i=1,...,N\)). \(\sum \limits ^{(N)}_{i<j}\) means a summation over all possible pairs (i, j) chosen from \(\{1,2,...,N\}\) for \(i<j.\)

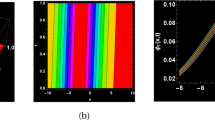

Below, we have plotted the one-, two-, three-soliton solution of Eq. (15). Figure 2 displays one, three, four divided waves, separately. Moreover, it is possible to construct any number of waves for Eq. (3) with Eq. (18) and diverse patterns of the wave can be obtained in terms of manipulating the value of \(x,p_i,\omega _1,l_1.\) For instance, Fig. 3 demonstrates one-shock wave with different values of \(x,p_1,\omega _1,l_1.\) Numerical evidence indicates that the increase of x makes the wave travel longer in t-axis and \(l_1\) influences the amplitude of the wave, the greater \(|l_1|\), the higher amplitude. For \(p_1\) and \(\omega _1\), they affect both the distance and the amplitude, but quite different effect. As shown in Fig. 3b, as \(p_1\) grows, the wave moves along the t-axis and the amplitude decreases. In Fig. 3c, as \(\omega _1\) grows, the wave moves towards the negative direction of t-axis and the amplitude decreases. Figs. 4 and 5 illustrate two- and three-shock waves with different values of \(x,p_1,p_2,\omega _1,l_1\) and \(x,p_1,p_2,p_3,\omega _1,l_1.\) These parameters function just the same as in Fig. 3.

Density profile of Eq. (15) with \(y=z=0\), (a) \(p_1=1,\omega _1=-3,x_{1,0}=1\), (b) \(p_1=p_2=1,\omega _1=-\omega _2=-5,x_{1,0}=1,x_{2,0}=2\), (c) \(p_1=p_2=p_3=1,\omega _1=-\omega _2=-5,\omega _3=2,x_{1,0}=1,x_{2,0}=2,x_{3,0}=3.\).

Sectional profile of Eq. (18) with \(m=1\),\(\mathcal {J}_0=y=z=0\), \(x_{j,0}=0\), (a) \(p_1=5,\omega _1=16,l_1=-725/5\), (b) \(\omega _1=16,l_1=-725/5,x=80\), (c) \(p_1=5,l_1=-725/5,x=80\), (d) \(p_1=5,\omega _1=16,x=80\).

Sectional profile of Eq. (18) with \(m=2\),\(\mathcal {J}_0=y=z=0\), \(x_{j,0}=0\), (a) \(p_1=5,p_2=7,\omega _1=16,\omega _2=27,l_1=-800/5,l_2=-2800/7\), (b) \(\omega _1=16,\omega _2=27,l_1=-800/5,l_2=-2800/7,x=80\), (c) \(p_1=5,p_2=7,\omega _2=28,l_1=-800/5,l_2=-2800/7,x=80\), (d) \(p_1=5,p_2=7,\omega _1=16,\omega _2=28,l_2=-2800/7,x=80\).

Sectional profile of Eq. (18) with \(m=3\),\(\mathcal {J}_0=y=z=0\), \(x_{j,0}=0\), (a) \(p_1=5,p_2=7,p_3=9,\omega _1=18,\omega _2=27,\omega _3=39,l_1=-725/5,l_2=-2760/7,l_3=-821\), (b) \(\omega _1=18,\omega _2=27,\omega _3=39,l_1=-725/5,l_2=-2760/7,l_3=-821,x=80\), (c) \(p_1=5,p_2=7,p_3=9,\omega _2=27,\omega _3=39,l_1=-725/5,l_2=-2760/7,l_3=-821,x=80\), (d) \(p_1=5,p_2=7,p_3=9,\omega _1=17,\omega _2=27,\omega _3=39,l_2=-2760/7,l_3=-821,x=80\).

Variable separation solution of (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq equation

As is address in the introduction, we have proposed a new variable separation solution

where \(\lambda _i(i=1,...,4)\) are constants to be determined later, \(\digamma _1[x],\digamma _2[y],\digamma _3[z],\digamma _4[t]\) are free functions. Next, we will use it to derive the folded localized excitation for Eq. (3). Substitution into Eq. (3), one has

where \(k_1,b_1,k_4,b_4\) are constants and \(\digamma _2,\digamma _3\) are free functions. Thus, Eq. (3) has following solution

Folded solitary wave

To establish folded localized excitations of u, it is essential using the freedom of \(\digamma _2,\digamma _3\), and set them to be suitable multi-valued functions. For example, set

where \(\varphi _i,\psi _i\) are localized excitations(\(\varphi _i(\pm \infty )=\psi _i(\pm \infty )=constant\)). One can make \(\xi \) multi-valued by taking \(\psi _i\) wisely in some regions of y. Hence, \(\digamma _2\) is M localized excitations as \(\xi |_{y\rightarrow \infty }\rightarrow \infty \) and may be multi-valued of y even if it is single-valued of \(\xi \). Actually, most of the multi-loop solutions are the special cases of Eq. (20). Based on above manner, first we choose \(\digamma _2=\textrm{sech}^2[\xi ],\digamma _3=\textrm{sech}^2[\theta ]\) and set z, y to be

where \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) are used to regulate the shape of the foldon. Below, we have plotted four types folded solitary wave in (y, z)-plane, by setting \(\alpha =-1.2,\beta =1\); \(\alpha =-2.5,\beta =0\); \(\alpha =-1.5,\beta =-1.5\); \(\alpha =-1.6,\beta =-1.6\). As we can see in Fig. 6a, b, there are two waves, one wave overlies another. While in Fig. 6c, d, two pipe-shaped solitary waves interact at (0, 0) and a peak rises at the intersection point.

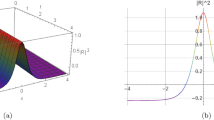

Secondly, we choose \(\digamma _2=\textrm{sech}^2[\xi ],\digamma _3=\textrm{sech}^2[\theta ]+\textrm{sech}^6[\theta ]\) and set z, y to be

where \(\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma \) are free parameters. In Fig. 7, the parameters are chosen to be \(\alpha =2,\beta =1,\gamma =-5.5\) and it shows a picture of superimposed multi-foldon. The sectional views Fig. 7b, c are plotted along y- and z-axis and demonstrate two-loop structure. Fig. 8 is plotted by choosing \(\alpha =2,\beta =1,\gamma =-10\).

Variable separation solution (19) of Eq. (3) with \(\lambda _1=\lambda _2=\lambda _3=\lambda _4=1,k_1=b_1=k_4=b_4=1\), \(\digamma _2=\textrm{sech}^2(\xi ),\digamma _3=\textrm{sech}^2(\theta )\), \(x=t=0\), (a) \(z=\xi -\textrm{tanh}[\xi ],y=\theta +\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]\), (b) \(z=\xi -2.5\textrm{tanh}[\xi ],y=\theta \), (c) \(z=\xi -1.15\textrm{tanh}[\xi ],y=\theta -1.15\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]\), (d) \(z=\xi -1.6\textrm{tanh}[\xi ],y=\theta -1.6\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]\).

Variable separation solution (19) of Eq. (3) with \(\lambda _1=\lambda _2=\lambda _3=\lambda _4=1,k_1=b_1=k_4=b_4=1\), \(\digamma _2=\textrm{sech}^2(\xi ),\digamma _3=\textrm{sech}^2(\theta )+\textrm{sech}^6(\theta )\), \(x=t=0\), \(z=\xi +2\textrm{tanh}[\xi ]+\textrm{tanh}^2[\xi ]-5.5\textrm{tanh}^3[\xi ],y=\theta +2\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]+\textrm{tanh}^2[\theta ]-5.5\textrm{tanh}^3[\theta ]\), (a) 3D plot, (b) sectional view along z-axis, (c) sectional view along y-axis.

Variable separation solution (19) of Eq. (3) with \(\lambda _1=\lambda _2=\lambda _3=\lambda _4=1,k_1=b_1=k_4=b_4=1\), \(\digamma _2=\textrm{sech}^2(\xi ),\digamma _3=\textrm{sech}^2(\theta )+\textrm{sech}^6(\theta )\), \(x=t=0\), \(z=\xi +2\textrm{tanh}[\xi ]+\textrm{tanh}^2[\xi ]-10\textrm{tanh}^3[\xi ],y=\theta +2\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]+\textrm{tanh}^2[\theta ]-10\textrm{tanh}^3[\theta ]\), (a) 3D plot, (b) sectional view along z-axis, (c) sectional view along y-axis.

In addition, we introduce a free parameter to simulate the evolution behaviour of the foldons. Here, \(\digamma _2,\digamma _3\) are set to be

where C is free parameter used to regulate the position, ranging from \(-10\) to 10. For convenience, we call it “time”. As we can see in Figs. 9 and 10, it depicts the chase-after phenomenon between one pipe-shaped foldon and two stripe foldon. Two stripe foldons move along the positive z-direction while the pipe-shaped foldon keeps still, crossing the stripe foldons. The shorter stripe foldon travels faster than the bigger one and they meet with each other at the moment \(C=0\)(see Figs. 9c, 10c). Here, they converge into a single large pipe-shaped foldon that has the maximum amplitude. The fact that Fig. 10a, e, as well as Fig 10b, d, are exactly the same image in reverse order indicates that the collision is elastic.

Evolution progress of Eq. (19) with \(\lambda _1=\lambda _2=\lambda _3=\lambda _4=1,k_1=b_1=k_4=b_4=1\), \(\digamma _2=\frac{4}{5}\textrm{sech}^2[\xi ]+\frac{1}{2}\textrm{sech}^2[\xi +C], \digamma _3=\textrm{sech}^2[\theta ]\), \(x=t=0\), \(z=\xi -1.5\textrm{tanh}[\xi ]-1.5\textrm{tanh}[\xi -C],y=\theta -2\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]\), (a) \(C=-10\), (b) \(C=-6\), (c) \(C=0\), (d) \(C=6\), (e) \(C=10\).

Corresponding sectional view of Fig. 9 at \(y=0\).

Superimposed structure of folded solitary wave

In this section we will consider superimposed structure of folded solitary wave and analyze its corresponding dynamical behaviour. Firstly, let us restrain \(\digamma _2,\digamma _3\) as

where \(\gamma ,\mu \) are free parameters, \(\theta ,\xi \) are intermediate variables, C is a constant used to control evolution. Based on above expression, the evolutional plots are shown in Fig. 11 under the parametric selection: \(C=-10,0,15\) and \(\mu =\gamma =1.5.\) It models the interaction between two folded solitary waves and each of them is double-bell-shaped. Although the sectional view along y-axis is single-bell-shaped(see Fig. 11e), it is worth noting that the sectional view along z-axis displays a more complicated multi-valued structure(see Fig. 11d) and it may maps up to five values for some values of y(see the interval near \(y=-0.5\)). As we can see, there are two double-bell-shaped foldons(one shorter and one higher) at \(C=-10\). As C increases, two foldons integrate into a much bigger one foldon. After that, it divides into two. It is noteworthy that readers can found that the sectional plots do not match 3D plots since we actually draw the anti-folded solitary waves and reverse the pictures.

Evolution progress of two foldons of Eq. (19) with \(\lambda _1=\lambda _2=\lambda _3=\lambda _4=1,k_1=b_1=k_4=b_4=1\), \(\digamma _2=-\textrm{sech}^4[\xi +0.25C]-0.5\textrm{sech}^2[\xi -0.25C], \digamma _3=-\sin [\theta ]\), \(x=t=0\), \(z=\xi -\mu \textrm{tanh}[\xi -0.5C]-\gamma \textrm{tanh}[\xi +0.5C],y=\theta +2\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]-5.3\textrm{tanh}^3[\theta ]\), (a) \(C=-10\), (b) \(C=0\), (c) \(C=15\), (d) sectional view at \(z=0,C=0\), (e) sectional view at \(y=0,C=-10,1,15\).

Moreover, we select four different combinations of \((\mu ,\gamma )\): \(\mu =0.9,\gamma =0.1\), \(\mu =\gamma =0.1\), \(\mu =\gamma =0.9\), \(\mu =\gamma =1.5\) to investigate the superimposed structures of two folded solitary waves and y is chosen to be

As shown in Fig. 12, four pictures demonstrate their interaction states at \(C=0\), and can be classified as tent-shaped structure (Fig. 12a), peak-shaped structure(Fig. 12c), loop-shaped structure(Fig. 12b, d).

Interaction of two foldons of Eq. (19) with \(\lambda _1=\lambda _2=\lambda _3=\lambda _4=1,k_1=b_1=k_4=b_4=1\), \(\digamma _2=-\textrm{sech}^4[\xi +0.25C]-0.5\textrm{sech}^2[\xi -0.25C], \digamma _3=-\textrm{sech}^2[\theta ]\), \(C=x=t=0\), \(z=\xi -\mu \textrm{tanh}[\xi -0.5C]-\gamma \textrm{tanh}[\xi +0.5C],y=\theta +2\textrm{tanh}^2[\theta ]-5.3\textrm{tanh}^3[\theta ]\) (a) \(\mu =\gamma =0.1\), (b) \(\mu =\gamma =0.9\), (c) \(\mu =0.9,\gamma =0.1\), (d) \(\mu =\gamma =1.5\).

Multi-valued structure Fig. 11d provides us an inspiration to derive other pattern. Motivated by such idea, we pay attention to 2D geometric plot in (z, u)-plane under the selections: \(\digamma _2=-\textrm{sech}^4[\xi +0.25C]-0.5\textrm{sech}^2[\xi -0.25C]\) and \(\digamma _3=1.5\sin [\theta ],y=\theta +3\textrm{sech}[\theta ]-7\textrm{sech}^3[\theta ]\); \(\digamma _3=1.5\cos [\theta ],y=\theta +3\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]-7\textrm{tanh}^3[\theta ]\); \(\digamma _3=1.5\textrm{sech}[\theta ],y=\theta +3\sin [\theta ]-7\sin ^3[\theta ]\); \(\digamma _3=1.5\textrm{sech}[\theta ],y=\theta +3\cos [\theta ]-7\cos ^3[\theta ]\); \(\digamma _3=1.5\textrm{sech}[\theta ],y=\theta +3\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]-7\textrm{tanh}^3[\theta ]\); \(\digamma _3=1.5\textrm{sech}[\theta ],y=\theta +3\textrm{sech}[\theta ]-7\textrm{sech}^3[\theta ]\). As shown in Fig. 13, six novel structures have been obtained and at least of one variable of z will map into more than one value. These graphics can be sorted out as: double-loop pattern(Fig. 13c, e), anti-twisted double-loop pattern(Fig. 13a), anti-umbrella pattern(Fig. 13b), fin-shape pattern(Fig. 13d, f).

Sectional profile with with \(\lambda _1=\lambda _2=\lambda _3=\lambda _4=1,k_1=b_1=k_4=b_4=1\), \(\digamma _2=\textrm{sech}^4[\xi +0.25C]+0.5\textrm{sech}^2[\xi -0.25C]\), \(x=t=0\), \(z=C=0\), (a) \(\digamma _3=1.5\sin [\theta ],y=\theta +3\textrm{sech}[\theta ]-7\textrm{sech}^3[\theta ]\), (b) \(\digamma _3=1.5\cos [\theta ],y=\theta +3\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]-7\textrm{tanh}^3[\theta ]\), (c) \(\digamma _3=1.5\textrm{sech}[\theta ],y=\theta +3\sin [\theta ]-7\sin ^3[\theta ]\), (d) \(\digamma _3=1.5\textrm{sech}[\theta ],y=\theta +3\cos [\theta ]-7\cos ^3[\theta ]\), (e) \(\digamma _3=1.5\textrm{sech}[\theta ],y=\theta +3\textrm{tanh}[\theta ]-7\textrm{tanh}^3[\theta ]\), (f) \(\digamma _3=1.5\textrm{sech}[\theta ],y=\theta +3\textrm{sech}[\theta ]-7\textrm{sech}^3[\theta ]\).

Summary

In this work, a new (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq equation is put forward and investigated, which describes the long wavelength water wave in hydrodynamics. Firstly, we have derived periodic solutions in terms of Hirota’s bilinear form and ansatz, under certain condition. Three typical periodic solutions have been plotted in 2D and 3D, see Fig. 1. Secondly, taking Burgers equation as an auxiliary function, we have obtained n-soliton solution as well as n-shock wave. In addition, their mechanism has been systematically discussed by exploring the function of each parameter, see Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5. Last but not least, we have offered a brand new insight into deriving multi-valued soliton from (3+1)-dimensional and higher dimensional partial differential equation, and use it to establish folded localized excitation of Eq. (3). Moreover, we have studied the superimposed structures and interaction behaviours of folded solitary waves. A lot of novel structures have been constructed, see Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13. Compared with the other methods, the variable separation solutions obtained in this paper not only directly give the analytical form of the solution u instead of its potential \(u_y\), but also provide us a straightforward approach to construct localized excitation for higher order dimensional nonlinear partial differential equation. We believe the method given in current paper will be helpful in finding soliton and localized excitation solution for other nonlinear systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, N., Xuan, Z. X. & Sun, J. Y. Triple-pole soliton solutions of the derivative nonlinear Schrödinger equation via inverse scattering transform. Appl. Math. Lett. 125, 107741 (2022).

Chanda, S., Chakravarty, S. & Guha, P. On a reduction of the generalized Darboux–Halphen system. Phys. Lett. A. 382, 455–460 (2018).

Kudryashov, N. A. Lax pairs for one of hierarchies similar to the first Painlevé hierarchy. Appl. Math. Lett. 116, 107003 (2021).

Ruzhanskya, M. & Yessirkegenov, N. A comparison principle for higher order nonlinear hypoelliptic heat operators on graded Lie groups. Nonlinear. Anal-Theor. 215, 112621 (2022).

Hirota, R. The Direct Method in Soliton Theory (Springer, 2004).

Zang, L. M. & Liu, Q. P. A super KdV equation of Kupershmidt: Bäcklund transformation, Lax pair and related discrete system. Phys. Lett. A. 422, 127794 (2022).

Peregrine, D. H. Water waves, nonlinear Schrödinger equations and their solutions. Aust. Math. Soc. Ser. B. 25, 16–43 (1983).

Walker, D. A. G., Taylor, P. H. & Taylor, R. E. The shape of large surface waves on the open sea and the Draupner new year wave. Appl. Ocean Res. 26, 73–83 (2005).

Solli, D. R., Ropers, C., Koonath, P. & Jalali, B. Optical rogue waves. Nature 450, 1054 (2007).

Kibler, B., Fatome, J., Finot, C., Millot, G. & Dias, F. The peregrine soliton in nonlinear fibre optics. Nat. Phys. 6, 790–795 (2010).

Solli, D., Ropers, C., Koonath, P. & Jalali, B. Optical rogue waves. Nature 450, 1054–1057 (2007).

Dudley, J. M., Genty, G. & Eggleton, B. J. Harnessing and control of optical rogue waves in supercontinuum generation. Opt. Exp. 16, 3644–3651 (2008).

Ganshin, A., Efimov, V., Kolmakov, G., Mezhov-Deglin, L. & Mcclintock, P. Observation of an inverse energy cascade in developed acoustic turbulence in superfluid helium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 1–4 (2008).

Hohmann, R., Kuhl, U., Stockmann, H. J., Kaplan, L. & Heller, E. J. Freak waves in the linear regime: A microwave study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 1–4 (2010).

Montina, A., Bortolozzo, U., Residori, S. & Arecchi, F. T. Non-Gaussian statistics and extreme waves in a nonlinear optical cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 173901 (2009).

Ivancevic, V. G. Adaptive-wave alternative for the Black-Scholes option pricing model. Cogn. Comput. 2, 17–30 (2010).

Eigen, M. & Schuster, P. The Hypercycle: A Principle of Natural Self-Organization (Springer, 1979).

Höhmann, R., Kuhl, U., Stöckmann, H. J., Kaplan, L. & Heller, E. J. Freak waves in the linear regime: A microwave study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 1–4 (2010).

Arecchi, F. T., Bortolozzo, U., Montina, A. & Residori, S. Granularity and inhomogeneity are the joint generators of optical rogue waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15, 153901 (2011).

Cheung, C. Y., Li, S. P. & Szeto, K. Y. Microscopic detection of spin-dependent long range interactions. Phys. Lett. A. 155, 236–240 (1991).

Zhang, S. L., Lou, S. Y. & Qu, C. Z. New variable separation approach: Application to nonlinear diffusion equations. J. Phys. A-Math. Theor. 36, 12223 (2003).

Boiti, M., Leon, J. J. P., Martina, L. & Pempinelli, F. Scattering of localized solitons in the plane. Phys. Lett. A. 132, 432–439 (1988).

Dai, C. Q. & Zhang, J. F. Novel variable separation solutions and exotic localized excitations via the ETM in nonlinear soliton systems. J. Math. Phys. 47, 043501 (2006).

Dai, C. Q. & Yu, D. G. Soliton fusion and fission phenomena in the (2+1)-dimensional variable coefficient Broer–Kaup System. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 47, 741–750 (2008).

Dai, C. Q., Wang, Y. Y., Fan, Y. & Zhang, J. F. Interactions between exotic multi-valued solitons of the (2+1)-dimensional Korteweg-de Vries equation describing shallow water wave. Appl. Math. Model. 80, 506–515 (2020).

Wang, Y. Y. & Dai, C. Q. Caution with respect to “new’’ variable separation solutions and their corresponding localized structures. Appl. Math. Model. 40, 3475–3482 (2016).

Huang, L. L. On the dynamics of localized excitation wave solutions to an extended (3+1)-dimensional Jimbo–Miwa equation. Appl. Math. Lett. 121, 107501 (2021).

Tang, X. Y., Lou, S. Y. & Zhang, Y. Localized excitations in (2+1)-dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. E. 66, 046601 (2002).

Tang, X. Y. & Lou, S. Y. Extended multilinear variable separation approach and multivalued localized excitations for some (2+1)-dimensional integrable systems. J. Math. Phys. 44, 4000–4025 (2003).

Lou, S. Y. Localized excitations of the (2+1)-dimensional sine-Gordon system. J. Phys. A. 36, 3877 (2003).

Zheng, C. L., Fang, J. P. & Chen, L. Q. New variable separation excitations of (2+1)-dimensional dispersive long-water wave system obtained by an extended mapping approach. Chaos Soliton Fract. 23, 1741–1748 (2005).

Hu, H. C. & Lou, S. Y. New interaction property of (2+1)-dimensional localized excitations from Darboux transformation. Chaos Soliton Fract. 24, 1207–1216 (2005).

Dai, C. Q., Chen, X. & Wu, S. S. Exotic localized structures based on a variable separation solution of the (2+1)-dimensional higher-order Broer–Kaup system. Nonlinear Anal.-Real. 10, 259–265 (2009).

Wazwaz, A. M. & Tantawy, S. A. E. Solving the (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq and BKP-Boussinesq equations by the simplified Hirota’s method. Nonlinear. Dyn. 88, 3017–3021 (2017).

Xu, G. Q. & Li, Z. B. PDEPtest: A package for the Painlevé test of nonlinear partial differential equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 169, 1364–1379 (2005).

Vekslera, A. & Zarmi, Y. Wave interactions and the analysis of the perturbed Burgers equation. Physica D 211, 57–73 (2005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.F.L. and C.L.S. wrote the main manuscript text and L.Y., Y.S.Y., J.Y.W., M.T.Z. prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, C., Yang, L., Yan, Y. et al. Periodic, n-soliton and variable separation solutions for an extended (3+1)-dimensional KP-Boussinesq equation. Sci Rep 13, 15826 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42845-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42845-0

This article is cited by

-

Exploring Lump Solutions, Bifurcation, Sensitivity, and Chaotic Dynamics in the Extended KP-Boussinesq Equation

Journal of Nonlinear Mathematical Physics (2025)

-

Analytical Study of the (3+1)-Dimensional Hirota-Jimbo-Miwa Equation: Exact Solutions and Localized Excitations in Optical Field

International Journal of Theoretical Physics (2025)

-

Dynamic of bifurcation, chaotic structure and multi soliton of fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation arise in plasma physics

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Data-driven solutions and parameter estimations of a family of higher-order KdV equations based on physics informed neural networks

Scientific Reports (2024)