Abstract

Antibiotics are resistant compounds with low biological degradation that generally cannot be removed by conventional wastewater treatment processes. The use of yolk-shell nanostructures in spinning disc photocatalytic reactor (SDPR) enhances the removal efficiency due to their high surface-to-volume ratio and increased interaction between catalyst particles and reactants. The purpose of this study is to investigate the SDPR equipped to Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell thin film nanostructure (FCZ YS) in the presence of visible light illumination in the photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin (AMX) from aqueous solutions. Stober, co-precipitation, and self-transformation methods were used for the synthesis of FCZ YS thin film nanostructure and the physical and chemical characteristics of the catalyst were analyzed by XRD, VSM,, EDX, FESEM, TEM, AFM, BET, contact angle (CA), and DRS. Then, the effect of different parameters including pH (3–11), initial concentration of AMX (10–50 mg/L), flow rate (10–25 mL/s) and rotational speed (100–400 rpm) at different times in the photocatalytic degradation of AMX were studied. The obtained results indicated that the highest degradation efficiency of 97.6% and constant reaction rate of AMX were obtained under LED visible light illumination and optimal conditions of pH = 5, initial AMX concentration of 30 mg/L, solution flow rate of 15 mL/s, rotational speed of 300 rpm and illumination time of 80 min. The durability and reusability of the nanostructure were tested, that after 5 runs had a suitable degradation rate. Considering the appropriate efficiency of amoxicillin degradation by FCZ YS nanostructure, the use of Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO thin film in SDPR is suggested in water and wastewater treatment processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pharmaceuticals, including antibiotics, are a type of micropollutant that is increasingly being found in the environment. These substances can enter the environment through various sources such as wastewater from pharmaceutical production, improper disposal of medications, runoff from agricultural fields, and other human-related activities1,2,3. The presence of pharmaceuticals in the environment is concerning due to their resistance to degradation. They have been detected in various environmental samples worldwide, including wastewater treatment plant effluents, surface water, seawater, groundwater, soils, and sediments. This persistence is closely related to their bioresistant nature, which means they are not easily broken down by natural processes. Among pharmaceutical compounds, antibiotics have received particular attention because of their potential role in the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria4. Antibiotics are extensively used in human and veterinary medicine, as well as in aquaculture, to prevent or treat microbial infections5,6. Many antibiotics have been found to be recalcitrant, meaning they resist degradation, under aerobic conditions typically found in conventional wastewater treatment plants. As a result, these antibiotics can escape largely intact into the environment. To address the issue of antibiotic pollution, non-biological methods have been employed for their treatment7,8. These methods include advanced oxidation processes, membrane separation, adsorption, coagulation, and various combinations thereof9. Researchers have conducted numerous studies in this field, and comprehensive reviews have summarized the most representative findings. Amoxicillin (AMX) is a semi-synthetic β-lactam antibiotic commonly used in human medicine to treat various diseases. It is also used in veterinary practice as a growth promoter. AMX is excreted from the body with minimal metabolism, so it is likely to be found in environmental samples rather than in the form of metabolites. It has been detected at concentrations in the µg/L range in environmental samples, including secondary treated effluents and surface water. In some cases, the concentration of AMX in antibiotic manufacturing effluents can reach the mg/L level10. Overall, the presence of pharmaceuticals, particularly antibiotics, in the environment is a significant concern due to their potential ecological and human health impacts. Efforts are being made to develop and implement effective treatment methods to minimize their release into the environment and mitigate the development of antibiotic resistance11,12.

All advanced oxidation processes are based on the production of free radicals with high oxidizing power such as hydroxyl radicals and superoxide radicals13,14. Advanced oxidation processes include photocatalytic processes, Fenton process, photofenton process and ozonation process. The use of conventional methods and techniques, such as adsorption or coagulation, transports pollutants to another phase and rarely degrades or removes them15. Other conventional methods, such as sedimentation, filtration, and membrane, have high operating costs or produce a hazardous by-product16. This has led to the rapid development of advanced oxidation processes. Because of AOP processes, instead of separating or transferring the pollutant to another phase, it directly degrades them and converts them into harmless substances such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). Therefore, this process is very important from an environmental point of view17.

Conventional photocatalysis reactors, which are carried out with powder catalysts in batch systems, suffer from slow reaction kinetics and are costly and difficult to industrialize, principally due to demands for separation equipment to cope with the powder catalyst18. In photocatalytic processes, deposited thin film catalysts have become significantly favorite to treat the need for the post-segregation phase needed with powders, howsoever this results in mass transfer limitations due to decreased concentration gradients and surface area of catalyst in the liquid solution19,20. Therefore the spinning disc reactor has been pursued as a process intensification technology for the photocatalytic degradation of pollutants in water bodies in order to prevail these problems21. In the SDR, the aforementioned limitations can be overcome by coating the catalyst on a substrate with strict adhesion, not reducing the catalyst activity and surface area22,23. The convenient light distribution within the reactor and adequate mass transfer between the pollutants and catalysts are the main design criteria in this kind of photocatalytic reactor24. These photocatalytic reactors can be established in two forms, the slurry system that the catalyst is suspended in the liquid solution, and the catalyst-immobilized system that includes the deposition of the catalyst on an appropriate substrate25. The slurry system needs catalyst segregation and recovery at the finite of the photocatalytic reaction which may increase the operational costs and reduce the mass transfer rate and system efficiency26,27. To eliminate these limitations, deposited photocatalytic reactors have been expanded by coating the catalyst onto different substrates such as glass, Teflon, ceramic, zeolite, alumina, and stainless steel22. A suitable substrate should have favorable bonding sites and surface, suitable adhesion to the catalyst, excellent photocatalytic activity, superior thermal and mechanical durability, corrosion resistance, and self-cleaning features27,28.

Photocatalytic heterogeneous innovation, which belongs to advanced oxidation processes, has emerged as a highly promising approach for the removal of organic pollutants in wastewater. It offers several advantages such as low cost, non-toxicity, low energy requirement, safety, reusability, and the ability to completely degrade organic compounds29. Among semiconductor oxides, ZnO is a widely used photocatalyst due to its easy accessibility and affordability30. Numerous studies have investigated the photocatalytic activities of ZnO in various forms, including powder and thin film, against different pollutants31,32. However, photocatalysts prepared in powder form often suffer from activity losses due to difficulties in separation from the solution medium33. To overcome these issues, the thin film structure has been employed, which enhances photocatalytic performance. Nevertheless, it has been reported that losses of photocatalyst occur on the external layer of the thin film during repeated experiments34.

Because of its natural abundance as a starting material, low cost production processing, nontoxic makeup, and reasonably good electrical and optical properties, copper oxide (CuO) has been investigated as a p-type semiconductor material with narrow band gap. In many applications, such as catalysis, photocatalysis, humidity and gas sensors, CuO with a lower band gap between 1.2 and 1.9 eV is typically used35. Due to the rapid recombination of electron–hole pairs generated by light, the CuO, however, displayed low photocatalytic activity. Effectively reducing the recombination of photogenerated electrons-holes can be achieved by binding CuO to other materials, such as ZnO or TiO236,37. Re-collection of NPs from treated water is another issue with CuO NP applications in industry, which drives up costs and taints the water that has been treated. Using magnetic photocatalysts such as Fe3O4 to solve these issues is a potential solution38. Increasingly, the morphology change of the catalyst is a significant manner to progress photocatalytic exclusivity39. It has been demonstrated that the fluorescence wavelength, quantum yields and their half-life would be modified by growing a shell of another semiconductor such as Au@TiO2, Fe3O4@Au, etc40,41. The hollow nanostructure has been enticed much heed because of its vast specific surface area and plentiful active sites of the catalyst. Alongside, light will be reflected and scattered repeatedly in the hollow internal cavity, so that to decline the propagation interval of electron–hole pairs and uttermost the usage of light41. For better progress the photocatalytic efficiency in yolk-shell nanostructure, which involves the core inside a void space cinctured by a semiconductor shell, has been expanded. This nanostructure contains the preferences of both hollow structure and core–shell structure42,43.

Spinning disc photocatalytic reactors are a type of photocatalytic reactor used for carrying out photocatalytic reactions. In these reactors, a disc is placed horizontally and rotates rapidly around its axis. A catalyst is placed on the surface of the disc, which initiates chemical reactions using sunlight or other light sources. In these reactors, catalysts (usually nanoparticles) are used as light absorbers and, upon light irradiation, they excite electrons from the valance band to conduction band. These electrons then interact with the molecules present at the reaction site and initiate chemical reactions. Spinning disc photocatalytic reactors offer several advantages, including increased catalyst-light contact area, high efficiency in pollutant removal, and uniform light distribution, making them particularly important44.

In this study, we developed and fabricated a visible-light-driven thin-film photocatalyst with a type of yolk-shell nanostructure supported by SDPR as advanced intensification system. The photocatalyst incorporated Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell nanostructure film and was designed specifically to investigate the degradation of amoxicillin (AMX), a representative antibiotic found in aqueous media. The system was equipped with blue LED lamps, which were adjustable in intensity by modifying their distance from the SDPR. This adjustment allowed for compensation of non-uniform light distribution and achieved effective light penetration depth, thereby minimizing the necessary light exposure to activate the catalyst. To deposit the visible light-activated Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell photocatalyst thin film, we utilized the spin coating technique on a spinning ceramic disc substrate. Spin coating involves the application of a liquid precursor solution onto a rotating substrate, resulting in the formation of a uniform thin film. Furthermore, we explored and optimized the effects of various factors including pH, initial AMX concentration, flow rate, and rotational speed. These factors play a crucial role in determining the efficiency of the photocatalytic degradation process. Overall, our study aimed to design and fabrication a novel yolk-shell thin film as a visible-light-driven photocatalyst. This thin film successfully facilitated the AMX degradation as a representative antibiotic in aqueous environments.

Materials and methods

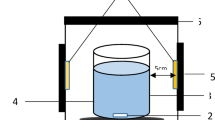

The SDPR consist of a rotating disc (disc diameter = 20 cm) to form cylindrical on which FCZ YS nanostructure catalyst is deposited. The disc was irradiated from above and the distance between light source (blue LED lamp, light intensity 13 mW/cm2) and the disc surface was kept constant in all experiments.

Chemical reagents

Copper nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO3)2.3H2O), Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2.6H2O), Ferrous chloride tetrahydrate(FeCl2∙4H2O), Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3∙6H2O), 3-Aminopropyl triethoxysilane (APTES), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), ammonium hydroxide (NH3OH, 25% w/w) and other reagents and solvents were purchased from the Merck company (Darmstadt, Germany, www.merck.de). Amoxicillin (purity 99%) was obtained from Dana pharmaceutical company, Iran. All abovementioned reagent and solutions were used without any further purification. Deionized (DI) water with a resistivity of > 18 MΩ cm was applied in all experiments.

Set up of spinning disc photocatalytic reactor

A spinning disc photocatalytic reactor (SDPR) was applied for the AMX photodecomposition in aqueous solutions as shown in Fig. S1. The operation mechanism of the spinning disc photocatalytic reactor has been described in previous articles44,45. In the SDPR, AMX degradation was performed under visible light irradiation by coating a FCZ YS thin film photocatalyst on a ceramic rotating disc. This photocatalytic reactor was equipped in a glass cylindrical encasement, an amended rotating ceramic disc with a catalyst, and blue LED lamps. The mixture of AMX solution enters the storage tank and is poured onto the disc center by a distributor. The distributor is a nozzle with five holes. Inside the reactor that disc can be rotated to range of 100–400 rpm AMX solution moves exterior through the disc edge due to centrifugal force, the liquid is sprinkled on the rotating disc and thinner solution films and very fine droplets could be formed. This system result in promoting the mass transfer coefficient and significantly declines the reactor size compared to conventional photocatalytic reactor45. The blue LED lamp is installed above the fixed encasement to supply the light source. The SDR has a control box system for alignment of the disc rotational speed, switching on/off the blue LED lamp, switching on/off the pump (air and water), motor, and mixer. Under LED visible light irradiation, the photocatalytic degradation procedure was carried out in a spinning disc reactor. The reactor was cylindrical Pyrex glass sealed with aluminum foil to remove extra light. The pollutant concentrations was quantified using UV–Vis spectrophotometer (JASCO, V 730). The pH was adjusted using pH meter type 827 pH Lab-metrohm.

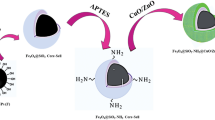

Synthesis of Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell

Synthesis of pure Fe3O4 magnetics nanoparticles

Pure Fe3O4 magnetics nanoparticles (MNPs) were synthesized through the co-precipitation method of Fe3+ and Fe2+ ions (molar ratio 2:1) in alkali solution. FeCl3∙6H2O (6.1 g) and FeCl2∙4H2O (2.35 g) were dissolved in 100 mL deionized water and kept at 90 °C for 10 min under continuous magnetic stirring and N2 atmosphere (Fig. S2). Following, NH3OH (10 mL) was added dropwise and then separated with an external magnet. The obtained Fe3O4 MNPs were rinsed with distilled water and ethanol for three times to remove impurities and then dried in the oven at 60 °C for 12 h.

Synthesis of Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell nanostructures

The Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell nanostructures (FS) were synthesized by a modified Stöber method46. Firstly, the as-prepared 1 g Fe3O4 MNPs were dispersed into a mixed solution of 100 mL of methanol and 16 mL of deionized water by ultrasonic for 30 min. Next, in a round bottom flask 2 necks, 5 mL ammonia hydroxide solution (25%) and 3 mL TEOS were added into the above mixture solution and stirred for 24 h. Then, the final products after separation by external magnet were washed with deionized water and HCl (0.1 M) for three times, and dried in an oven at 70 °C for 8 h (Fig. S3).

Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell nanostructures surface modification

A solution of the Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2 (FSN) nanostructures was prepared by mixing 2 g Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell NSs in 80 mL of methanol and stirred by ultrasonic for 15 min. Then 5.3 mL APTES was added to mixed solution and under magnetic stirrer and reflux at 65 °C for 24 h until the reaction was complete. The resultant product after separation by external magnet was dried in an oven at 70 °C for 10 h (Fig. S4).

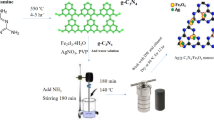

Synthesis of Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2@CuO/ZnO core–shell nanostructures

The Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2@CuO/ZnO core–shell (FSCZ) composite were synthesized using a hydrothermal process. In this three-step method, first, 1.115 g Zn(NO3)2.6H2O and 1.8 g Cu(NO3)2·3H2O were dissolved in 75 mL deionized water. Second, 0.5 g Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2 core–shell nanostructures was dissolved in 50 mL deionized water. Then, 15 mL NH3OH were added drop wise to the mixed solution of the previous two steps and kept under a magnetic stirrer for 24 h. Finally, after separation by external magnet and washing several times with distilled water and ethanol, the resulting product was dried in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h (Fig. S5).

Synthesis of Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell nanostructures

The Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell (FCZ YS) composite were synthesized using a self-transformation process (Fig. S6). Briefly, 1 g of the as-synthesized Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2@CuO/ZnO core–shell NSs were dispersed in 50 mL deionized water by ultrasonication for 15 min and then was kept at 70 °C for 48 h until the SiO2 shell is removed and to form the yolk-shell structure through a self-transformation process47. Afterward, the yolk-shell structure were collected by magnet and washed with ethanol and DI water and dried at 60 °C for 24 h thoroughly in vacuum oven.

Deposition of Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell NSs thin film on the disc

The Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell thin film was deposited on ceramic disc substrate by sol–gel spin coating method (Fig. S7). Prior to film deposition, the ceramic disc substrate was cleaned and washed thoroughly with acetone, ethanol solutions and DI water and then dried for any contamination and precipitation removal at 100 °C for 1 h. At first, 1 wt% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) in 25 mL DI water was placed in a sealed container for 3 h at 80 °C (to promote complete swelling) in ultrasonic bath to access a transparent solution. Afterward, to achieve a homogenous solution 40 g/L of as synthesized Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell NS was dissolved in 25 ml DI water. The mixture of Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell NS and PVA solutions was subjected to ultrasonication for 1 h until a homogeneous solution was obtained. The new solution obtained was used for the deposition of a ceramic disc by spin coating at a speed of 1000 rpm for 60 s. In order to reach the desired deposition, five layers were placed on the disc and dried at 60 °C for 15 min after each coating, and finally at 250 °C for 1 h in a vacuum oven.

Results and discussion

Characterization of nanostructured photocatalysts

The nanostructure photocatalysts were characterized by Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM TESCAN MIRA3 and FE-SEM Zeiss-Sigma 300), Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM, Philips EM 208S), X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV, Japan), UV–Visible Spectrophotometer (JASCO V-730, Japan), and Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM, MDK VSM, Iran). Atomic Force Microscope (AFM Nanowizard 2, JPK company, Germany), Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS S-4100 SCINCO), Contact angle (Contact angle CAG-20), and BET (BELSORP mini II, Japan).

XRD analysis

XRD patterns were prepared using a Rigaku Ultima IV apparatus with Cu Ka radiation (wavelength, l = 1.5418 Å). X-ray diffraction analysis is noticed as a favorable method in the recognition of a crystal structure and crystallographic pattern of as-prepared samples. Figure S8a–c represents the XRD patterns of Fe3O4, Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell nanostructure, and Fe3O4@SiO2@CuO/ZnO core–shell nanostructure. As illustrated in Fig. S8-a, an good agreement between the XRD pattern of Fe3O4 MNPs in the present study and those recorded in JCPDS No: 088-0315, peak list: 30.16° (220), 35.52° (311), 43.17° (400), 53.56° (422), 57.1° (511) and 62.7° (440) was found48. Impurity peak is not observed. Compared with Fig. 1a, the coating of SiO2 layer brings slight decrease in intensity to the XRD pattern of Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell (Fig. S8-b) that can be cause the existence of amorphous silica. After coating zinc oxide (ZnO) and copper oxide (CuO) grains on the surface of the Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell nanostrucure (Fig. S8-c), several new peaks appear at 2θ 31.77, 34.42, 36.25, 47,54, 56.6, 62.86 and 67.96 which can be indexed to the ZnO hexagonal wurtzite phase (JCPDS card No. 36-1451) and at 2θ 32.51, 35.45, 55.35, 38.73, 38.92, 48.76, 61.57 and 68.14 which can be indexed (110), (002), (− 111), (111), (200), (− 202), (− 113) and (220) to the monoclinic copper oxide(JCPDS card No. 005-0661), respectively.

The crystal structure of pristine disc (PD) and Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO photocatalytic film was investigated using XRD analysis (Fig. 1). The XRD pattern in Fig. 1a of the important peaks of the ceramic substrate at 2θ including zirconium with crystal planes (101), (002), (112), (211) and (213), titanium dioxide with crystal planes (400), (002), (501) and (402) and sillimanite with crystal planes (141), (320) and (324) is attributed. The peaks formed in coating the photocatalyst film on the ceramic substrate are the same as the peaks in the Fig. S8-c, which confirms the proper film of the yolk-shell structure on the ceramic substrate.

VSM analysis

VSM pattern of pure Fe3O4, Fe3O4@SiO2, Fe3O4@SiO2@CuO/ZnO core–shell and Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell nanostructure are examined in Fig. 2 at room temperature under an external magnetic field from − 10,000 to 10,000 Oersted (Oe). Magnetic saturation values of 58.92 emu/g for pure Fe3O4, 39.34 emu/g for Fe3O4@SiO2 were shown, which in both samples show paramagnetic properties for optimal separation (Fig. 2a, b)49. The decrease in the magnetic properties of Fe3O4@SiO2 in Fig. 2b compared to pure Fe3O4 can be due to the coating of the magnetic Fe3O4 core by the non-magnetic coating TEOS (SiO2) as a shell50. These results showed that Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles were significantly reduced by adding SiO2 and amino propyl groups (APTES). The reason is mainly attributed to the presence of non-magnetic materials on the surface of nanoparticles51. Also, in Fig. 2c where Fe3O4@SiO2@CuO/ZnO core–shell and Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell samples were examined, the results showed that the magnetic behavior of Fe3O4@SiO2@CuO/ZnO core–shell nanostructure decreases with the addition of CuO and ZnO to Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell was 10.77 emu/g. Although the magnetic saturation has decreased from 58.92 emu/g for Fe3O4 to 10.77 for Fe3O4@SiO2@CuO/ZnO core–shell nanostructure, but the synthesized core–shell nanostructure still maintain their magnetic properties and behavior. The saturation magnetization for Fe3O4@void@CuO-ZnO yolk-shell nanostructure is about 8.61 emu/g, which could be easily separated from the solution by making use of an external magnetic field (Fig. 2d)52,53.

FE-SEM analysis

FESEM is one of the ways to investigate the nanostructure of a material, including its appearance, surface structure, particle size, and the presence of impurities. Figure S9 shows the FESEM images and EDX of Fe3O4@SiO2 magnetic core–shell nanostructure, Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2, Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2@CuO-ZnO core–shell and Fe3O4@void@CuO-ZnO yolk-shell. All the images show that the shape of the particles is almost spherical and has nanometer dimensions. According to Fig. S9-a, the increase in particle size by 76.36 nm compared to the size of Fe3O4@SiO2 and particles modified with TEOS indicates the presence of a layer on Fe3O4 MNPs. The average particle size in the Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2 core–shell nanostructure (FSN) is 81.84 nm, which is due to the addition of an organic amine coating (APTES) on the Fe3O4@SiO2 core–shell nanostructure and for this reason, the size of the particles has become larger compared to the Fe3O4@SiO2 nanostructure (Fig. S9-c51. Also, Fig. S9-e and g show Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2@CuO-ZnO core–shell and Fe3O4@CuO-ZnO yolk-shell nanostructures. The results showed that the particle size was 103.22 nm in the core–shell structure and 81.36 nm in the yolk-shell structure. The reason for the reduction in the size of the yolk-shell structure is due to the removal of the SiO2 layer in core–shell structure.

The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) technique is indeed a convenient method for detecting elements and their weight or atomic percentages in a material. The presence of Fe, Si, and O signals in the EDX analysis indicates that Fe3O4 nanoparticles are loaded into silica (SiO2). This suggests that the Fe3O4 nanoparticles are embedded within the silica matrix (Fig. S9-b). Regarding other nanostructures, the constituent elements are known in Fig. S9d, f and h. The TEM image in Fig. S9-i depicts that CuO and ZnO particles were stoutly linked and distributed on the external surface of the shell without detriment to the yolk-shell structure.

Figure 3 shows the results of the cross-sectional and top of view FE-SEM analyses of the FCZ YS NS film on the surface of the ceramic disc. The FE-SEM images shown in Fig. 3a, was confirmed that the FCZ YS NS consists of spherical structures of 74.67 nm in average size on the disc surface. From the Fig. 3b. it has been found that the average thickness of the FCZ YS NS film was about 6 μm. Figure 3c depicts the EDX spectra for deposited thin film in the disc with quantitative elemental distribution. This result depicts that the PD-FCZ YS nanostructure film enhanced the mass transfer rate and initial adsorption of AMX, which result in the photocatalytic activity.

Optical analysis

The UV–visible diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) patterns was used to characterize the optical characteristics of the nanostructures of Fe3O4, Fe3O4@SiO2, Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2 Core–Shell and Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO Yolk-Shell film. Figure 4 depicts that the absorption peaks of the prepared nanostructures were observed within the average UV–Vis absorption terrain [5, 17]. As Fig. 4 shows, the band gap energy (Eg) for magnetic nanoparticles of Fe3O4, Fe3O4@SiO2, and Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2 are 4.7 eV, 3.65 eV and 3.57 eV, respectively. Compared to the Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2 Core–Shell sample, the Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO Yolk-Shell film sample show enhanced absorption in the visible light region (1.89 eV). The reason for this is, on the one hand, due to the increase in the concentration of CuO in the synthesized sample, because CuO is in the visible light region, and on the other hand, the size of the particles can be described according to the FESEM images38. This means that as the size of the particles decreases to nano dimensions, their energy levels change from continuous to discrete. Because in normal materials, energy band band are continuous, but in nanomaterials, these bands are discrete. The smaller the size of the nanoparticles, the larger the band gap, and the larger the size of the nanoparticles, the smaller the band gap. Energy band gap increases with decrease in size of the nanoparticles due to electron restriction at nano-size so called “quantum size effect”. Therefore, the change in the band gap is caused by the quantum size effect and the surface effect of Fe3O4, Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2 and Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell nanostructures54,55,56,57.

AFM and contact angle analysis

Figure 5 AFM 2D and 3D images of pristine disc and FCZ YS deposited on a disc substrate. The AFM images of pristine disc and FCZ yolk-shell NS films are shown in Fig. 5a, b and d, e. AFM analysis has been used to describe the roughness of the substrate and the photocatalytic film coated on the ceramic disc. As shown in the figure, the substrate of the ceramic disc shows a relatively rough surface (average roughness 18.76 nm), while the photocatalytic film shows a higher surface roughness (average roughness 38.4 nm). This increase in surface roughness can be attributed to the presence of a thin film of FCZ yolk-shell nanostructure on the surface of the ceramic disc. The rough surface of the photocatalyst observed in the AFM image was similar to that of the FESEM, indicating the growth of the FCZ yolk-shell nanostructure catalytic film on the substrate surface of the ceramic disc.

One of the important features of the surface is wettability. The Wettability behavior of a surface can be determined by the measurement of the contact angle. The hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of the immobilized surfaces by FCZ YS photocatalytic film were appraised by water contact angle measurement. The result showed that the hydrophilicity of FCZ YS photocatalytic film is satisfactory (Fig. 5c and f). However, the contact angle reduced upon the formation of FCZ YS photocatalysts film on the ceramic disc surface, enhancing the wettability of the coated disc substrate. An increase in hydrophilicity improved physical features and surface energy to reform the AMX adsorption as an initial monolayer.

BET analysis

The BET technique is a commonly used approach to describe the characteristics of porous materials with diameters ranging from 2-50 nm (meso) and 2 nm (micro)58. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms are depicted in Fig. 6. This figure displays that FSCZ CS NSs and FCZ YS NSs exhibits type IV isotherm and 3H hysteresis loop. The BET surface area of FCZ YS Ns is 62.48 m2/g, which is remarkably increased compared with 18.98 m2/g for the FSCZ CS Ns. FCZ yolk-shell nanostructure showed excellent adsorption and desorption capacity compared to the FSCZ core–shell, and according to the BET specific surface area in the FCZ yolk-shell, it was 3.29 times higher than the FSCZ core–shell nanostructure. Therefore, the number of active sites in FCZ YS Ns has been considerably enhanced and the reaction activity to deal with amoxicillin is increased considerably. The ratio of specific surface area of yolk-shell structure to core–shell (YS to CS ratio) was obtained by Li et al.59 0.95 and Shi et al.53 1.31. Table S1 shows the BET specific surface area in different core–shell and yolk-shell composites and specific surface area ratio of YS to CS. Also, the properties of porosity and specific surface area in the two mentioned structures are listed in Table S2.

Effect of parameters on photocatalytic degradation

In the process of photocatalytic degradation of AMX by FCZ YS thin film, four factors were optimized of pH, initial pollutant concentration, flow rate and disc rotation speed, respectively. Then, under optimal conditions, the effect of scavengers, mineralization (COD and TOC), reusability and durability of the thin film coated on the disc and comparing FCZ YS and FSCZ CS thin films were investigated.

Effect of pH

The pH of the solution plays an important role in the photocatalytic degradation processes of AMX, which is caused by the surface charge of the photocatalyst, the degree of ionization of AMX in the solution, and also the separation of functional groups in the photocatalyst sites. The AMX degradation efficiency is investigated in the pH range of 3–11, an initial AMX concentration of 50 mg/L, flow rate of 10 mL/s, disc rotational speed of 200 rpm and an illumination time of 90 min. The reaction under LED visible light illumination is studied using FCZ YS thin film. Figure 7 plots the degradation of AMX by photodegradation as a function of pH in the range of 3–11. The data achieved using LED visible light are depicted in the Fig. 7a for more comparison. As can be observed in Fig. 7a, the AMX degradation efficiency raises from pH 3 to pH 5, and then decreases from pH 5 to pH 11. In this research, pH 5 was distinguished as the optimum pH value, whereby the FCZ YS thin film photocatalyst has a maximum efficiency of 58.21% at pH 5. AMX and photocatalyst have different performance efficiency at different pH values due to different properties. The pH zero point charge (pHpzc) was determined using past studies60,61. As the pHpzc for the FCZ YS photocatalyst corresponds to 6.62, as observed in Fig. 7b, the photocatalyst surface is positive at pH < pHpzc and negative at pH > pHpzc. The removal efficiency decreases when the pH value goes above 5, reaching the lowest removal rate of 27.57% at pH 11. In Fig. 7b, it is shown that the surface of the yolk-shell nanostructure becomes negatively charged at pH values higher than the point of zero charge (pHzpc). This negative charge accumulation on the adsorbent's surface results in electrostatic repulsion between the catalyst and AMX. However, when the pH values are below the pHzpc, the catalyst surface carries a positive electrical charge. Since AMX is an anionic compound, there is an electrostatic attraction force between the yolk-shell nanostructure and AMX, causing AMX to degrade on the catalyst surface in an acidic environment. Therefore, pH 5 was chosen as the optimal pH value for the experiments, and all subsequent experiments were conducted at this pH value7,62.

Effect of initial AMX concentration

The effect of the initial concentration of AMX was investigated into 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg/L AMX solutions, respectively, under conditions of optimal pH = 5, flow rate of 10 mL/s, and disc rotation speed of 200 rpm during 90 min. As depicted in Fig. 8. highest AMX removal efficiency were observed at the initial concentrations of 10 mg/L (100%) and 20 mg/L (98.71%) at illumination times of 70 and 90 min, respectively. Then the degradation rate reduces with an increase in the initial AMX concentration from 20 to 50 mg/L. AMX degradation efficiency was optimized at 81.7% (30 mg/L), but it decreased gradually by enhancing the initial AMX concentration of 10 and 50 mg/L with degradation efficiency of 100–59.1%, respectively.

Higher degradation efficiency was obtained for AMX solution with lower starting concentrations. Because due to the surface area of the FCZ YS photocatalyst and the supply of oxidant due to the lower total number of AMX molecules, the degradation will be take place faster63. In the intensity of LED visible light radiation, the decrease in degradation efficiency with increasing concentration of AMX solution may be attributed to the competition between AMX molecules, the inhibition of intermediate compounds produced during the photodegradation process, and the decrease in the intensity of light reaching the surface of the FCZ YS catalyst. As Fig. 8 shows, at concentrations higher than 20 mg/L, more light was scattered by the AMX solution and fewer photons are able to reach the FCZ YS catalyst surface, which will largely result in the reduction of electron–hole pair production. As a result, the degradation efficiency decreases with increasing concentration from 20 to 50 mg/L. Since the degradation efficiency of AMX in concentrations of 10 and 20 mg/L are close to each other. Therefore, to optimize the factors of flow rate and disc rotation speed, the initial concentration of 30 mg/L was investigated. When the AMX concentration increases, more molecules are absorbed on the surface of the photocatalyst, so the need for active oxidant species such as hydroxyl radicals and superoxide increases in order to decompose this high concentration of AMX absorbed on the photocatalyst surface57,64. Also, the excess concentration absorbed on the surface of the catalyst prevents the absorption of light photons on the surface of the catalyst, as a result, the available active species are not enough to decompose the pollutant with high concentrations, and their deficiency increases with the increase of the pollutant concentration, and many organic compounds leave the reactor without being decomposed. On the other hand, light photons may be absorbed by the organic compounds adsorbed on the surface of the catalyst before they reach the surface of the photocatalyst and prevent access to the surface of the photocatalyst. In addition, during the photocatalytic oxidation process, intermediate compounds are produced that reduce the rate of mineralization or that are placed on the active sites of the catalyst surface and hinder the progress of the photocatalytic process65.

Effect of flow rate

The effect of solution flow rate on the degradation efficiency of AMX was studied under the conditions of pH = 5, initial AMX concentration of 30 mg/L, rotational speed of 200 rpm and illumination time of 90 min as the coating catalyst on the ceramic disc. The experimental results are depicted in Fig. 8. It can be seen from Fig. 8 that the degradation efficiency of AMX increases with the increasing of flow rate from 10 to 15 mL/s and then decreases from 15 to 25 mL/s. When the flow rate was 10 mL/s, the degradation efficiency was 82.4% after illumination time of 90 min. Therefore, when the flow rate increased to 25 mL/s, the degradation efficiency reached 56%. Three potential reasons are effective in reducing and increasing the flow rate. According to Fig. 9, at a flow rate of 10 mL/s, there is a possibility of breaking down the liquid film and improper distribution of the liquid flow on the disc, as a result, the mixing ability of the liquid film reduces and the decomposition efficiency decreases (at lower flow rate)66. In such cases, by increasing the flow rate from 10 to 15 mL/s, the interface between solid–liquid (the FCZ YS catalyst particles and amoxicillin molecules) increased, thus increasing the mass transfer rate and increasing the degradation efficiency (In favorable flow rate). Another reason for the decrease in degradation efficiency with the increase in flow rate from 15 to 25 mL/s can be attributed to the decrease in the residence time of amoxicillin molecules on the disc, which has reduced the exposure time of FCZ YS catalyst to light. On the other hand, with the increase in the flow rate, thicker films of liquid are formed on the disc, which has led to the reduction of the solid–liquid interface and ultimately the efficiency of degradation. Also, with the thickening of the liquid film, the depth of light penetration and the activity of the catalyst have decreased, for this reason, the degradation efficiency has decreased to 56% at the flow rate of 25 mL/s (at higher flow rate)67.

Effect of rotational speed

The rotational speed in SDR is one of the most efficient operation factors influencing the photocatalytic removal. This factor is dependent on the liquid film thickness and the mass transfer coefficients of pollutants68. The photocatalytic performance of SDR was investigated under different rotational speed (100–400 rpm) in the photodegradation of AMX as a resistant organic pollutant. The removal efficiency of AMX increases with increasing disc rotational speed and then starts to reduce when the rotational speed trespasses 300 rpm as shown in Fig. 10. Below the optimum disc rotational speed, the photodegradation efficiency of AMX is low due to the increased thickness of the liquid film on the disc surface. On the other hand, above the optimal disc rotational speed, the removal efficiency decreases due to the low retention time68,69. Increasing the disc rotational speed from 100 to 300 rpm resulted in an increased degradation efficiency of AMX. This trend can be explained by the following factors: (1) Turbulence and Mixing: Increasing the rotational speed enhances turbulence and mixing within the system. This increased agitation promotes better contact between the AMX molecules and the photocatalyst coated on the disc’s surface, leading to a higher interfacial area for chemical reactions to occur. (2) Mass Transfer Rate: The faster rotational speed facilitates a greater mass transfer rate. As a result, a thin sheared liquid film and very fine droplets form on the disc’s surface. This further increases the contact area and enhances the interaction between the AMX molecules and the photocatalyst68,69. The behavior of the liquid can be divided into two parts: before and after reaching the optimum rotational speed. Before reaching the optimum rotational speed, there is a relationship between the rotational speed and the thickness of the liquid film on the disc, where the thickness gradually decreases the rotational speed increases until it reaches an optimal thickness (at a certain speed). After surpassing the optimal rotational speed, the thickness of the liquid film decreases with increasing rotational speed, leading to a decrease in the persistence of the liquid film on the disc and consequently reducing the reaction rate. Zamani et al.45 and Mirzaei et al.70 also obtained similar results. However, it's important to note that beyond a certain point, further increments in the disc rotational speed lead to a decrease in AMX decomposition efficiency. This decrement can be attributed to the reduction in the liquid residence time on the disc. When the rotational speed becomes too high, the liquid film spends less time in contact with the photocatalyst-coated surface, limiting the opportunity for effective degradation of the AMX molecules.

Effect of photolysis and adsorption

The treatment efficiency of amoxicillin solution was evaluated by photolysis, adsorption and photocatalyst processes under optimal conditions (Fig. 11). The AMX solution was experimented without the presence of a catalyst for photolysis and without the presence of visible light for the catalyst test at 30 min. The low decomposition efficiency of AMX under LED visible light without the use of a catalyst (photolysis process) can be attributed to the lack of oxidizing species. Therefore, the effect of photolysis in the degradation of amoxicillin is negligible. The catalytic activity of the FCZ YS film without the exposure of LED visible light was weak (adsorption process) because the catalyst needs light to activate sites and generate electron-holes. But when the FCZ YS catalyst film was exposed to LED visible light (photocatalytic process), the degradation efficiency increased dramatically. The presence of light activates the electron–hole and produces free radicals and increases the degradation efficiency.

COD and TOC removal

The intermediate compounds produced by the oxidation of initial pollutants could have adverse effects on degradation efficiency due to the adsorption competition on the catalyst surface or could be higher toxicity than the original pollutant71. Hence, it is necessary to achieve the compounds mineralization value through the appraisal of chemical oxygen demand (COD) and total organic carbon (TOC) amounts. The change in COD and TOC during the photocatalytic process in the spinning disc reactor under the optimal conditions is exhibited in Fig. 12. The COD and TOC removal efficiency were 75.2% and 63.5% after 80 min of illumination time, respectively. At the primary of the reaction, a scarce removal of COD and TOC were seen due to the production of intermediates in organic forms that also encompass carbon. More decomposition arisen in the intermediate organic compound leads to a remarkable decrease in COD and TOC in the later stages. These results corroborate the undertaking eventuality of the FCZ YS film for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment.

Effect of scavengers

To explain the photocatalytic degradation mechanism of AMX under experiment optimal conditions, the major active species produced in the photodecomposition process in SDPR were considered by evaluating the reactive oxygen species. In the active species quenching experiments, various scavengers such as triethanolamine (TEA, 1mM), benzoquinone (BQ, 1mM), and isopropanol (IPA, 1 mM) were used as an inhibitor of active holes (h+), superoxide radical \(\left( { \cdot {\text{O}}_{{\text{2}}} ^{ - } } \right),\), and hydroxyl radical (·OH), respectively72. The results presented in Fig. 13 illustrate the distinct roles of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the photocatalytic degradation of AMX when FCZ YS film is used. The researchers observed significant differences in the photo degradation rate of AMX upon the addition of IPA, TEA, and BQ compared to the control (no scavengers). Importantly, the addition of these scavengers had an adverse effect on the photocatalytic activity of FCZ YS film. Based on their findings, the order of reactivity for ROS on FCZ YS photocatalysts was determined as follows: BQ > IPA > TEA > no scavengers. This implies that benzoquinone (BQ) exhibited the highest reactivity towards ROS, followed isopropyl alcohol (IPA), by triethanolamine (TEA), and finally, the absence of scavengers. Consequently, it is concluded that O2 and OH radicals and are the main active species responsible for the photo-degradation of AMX when using FCZ YS film as the photocatalyst. These findings contribute to understanding the underlying mechanisms involved in the photocatalytic degradation process and elucidate on the role of specific ROS in the removal of AMX73.

Comparison of FCZ YS and FSCZ CS films

Figure 14 demonstrate the comparison of AMX degradation between FSCZ core–shell and FCZ yolk-shell films under optimal experimental conditions. In Fig. 14, it is observed that the FCZ yolk-shell film can degrade AMX up to 97.6% within 80 min. While, FSCZ CS film presents the degradation efficiency up to 93.75% at 90 min. This value is lower than that of the FCZ yolk-shell film. The improved catalytic performance of FCZ yolk-shell film can be attributed to their unique features. The cavity or hollow space within the yolk-shell layer acts as a nanoreactor and provides sufficient space and numerous active sites on the surface of the core and the void space between the core and the shell to carry out the reaction between AMX and the catalyst74. Furthermore, another reason can be attributed to the high specific surface area in the FCZ yolk-shell nanostructure compared to the FSCZ core–shell nanostructure (See section “BET analysis”). A larger surface area of the catalyst will have a higher number of active sites for adsorbing pollutant molecules. Consequently, the degradation efficiency increases, and the reaction time for the FCZ yolk-shell is reduced compared to the FSCZ core–shell film.

Reusability and durability of FCZ YS film experiment

Reusability and durability of a photocatalyst is an important factor controlling the long time performance of every photodegradation process. That's why, a study on the reusability and durability of FCZ YS film was conducted over recycling experiments. To investigate reusability and durability after each run, the FCZ YS film was taken out of the SDR and washed with DI water, and then dried at 80 °C for 3 h by the oven. The film was reused five times under the same reaction optimum operational conditions (pH = 5, initial AMX concentration of 30 mg/L, flow rate of 15 mL/s, rotational speed of 300 rpm and illumination time of 80 min) and the result is shown in Fig. 15. The results indicated that the performance of photocatalytic film remained unchanged in consecutive experiments. The FCZ YS film depicted great durability and sustained high photocatalytic activity after 5 runs, suggesting that the immobilized FCZ YS film on the ceramic disc was very durable and exhibited high potential for reusability.

Conclusions

In this study, the prepared novel Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell catalyst were successfully deposited on the ceramic disc surface of the SDPR by the spin coating method, and applied to the photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin pollutant in aqueous environments by LED visible light irradiation. The effects of different operational parameters (disc rotational speed, flow rate, pH, initial concentration of AMX, reaction time) on the degradation efficiency of AMX solution were investigated. The highest degradation efficiency of AMX were obtained under optimal conditions of pH = 5, the initial AMX concentration of 30 mg/L, the flow rate of 15 mL/s, rotational speed of 300 rpm and irradiation time of 80 min. Ultimately, the proper reusability and excellent durability of the prepared photocatalyst film were recorded with reproducibility of the photodegradation process for five runs at optimum conditions. According to the results obtained from the SDPR system and its excellent catalytic durability, it can be used as a proposed option on a scale-up for the treatment of pharmaceutical industry wastewaters.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abbasnia, A. et al. Removal of tetracycline antibiotics by adsorption and photocatalytic-degradation processes in aqueous solutions using metal organic frameworks (MOFs): A systematic review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 145, 109959 (2022).

Khan, A. et al. Impact, disease outbreak and the eco-hazards associated with pharmaceutical residues: A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 677–688 (2022).

Mahmoudian, M. H. et al. Statistical modeling and optimization of dexamethasone adsorption from aqueous solution by Fe3O4@ NH2-MIL88B nanorods: Isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamic. Environ. Res. 236, 116773 (2023).

Dehghan, A., Zarei, A., Jaafari, J., Shams, M. & Khaneghah, A. M. Tetracycline removal from aqueous solutions using zeolitic imidazolate frameworks with different morphologies: A mathematical modeling. Chemosphere 217, 250–260 (2019).

Dimitrakopoulou, D. et al. Degradation, mineralization and antibiotic inactivation of amoxicillin by UV-A/TiO2 photocatalysis. J. Environ. Manage. 98, 168–174 (2012).

Moradi, M. et al. CuO and ZnO co-anchored on g-C3N4 nanosheets as an affordable double Z-scheme nanocomposite for photocatalytic decontamination of amoxicillin. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 285, 119838 (2021).

Al-Musawi, T. J. et al. Degradation of amoxicillin under a UV or visible light photocatalytic treatment process using Fe2O3/bentonite/TiO2: Performance, kinetic, degradation pathway, energy consumption, and toxicology studies. Optik 272, 170230 (2023).

Homem, V. & Santos, L. Degradation and removal methods of antibiotics from aqueous matrices—a review. J. Environ. Manage. 92, 2304–2347 (2011).

AlAbduljabbar, F. A. et al. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutant in wastewater by electrospun functionally modified polyacrylonitrile nanofibers membrane anchoring TiO2 nanostructured. Membranes 11, 785 (2021).

Dehghan, S., Kakavandi, B. & Kalantary, R. R. Heterogeneous sonocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using ZnO@ Fe3O4 magnetic nanocomposite: Influential factors, reusability and mechanisms. J. Mol. Liquids 264, 98–109 (2018).

Le, S., Ma, Y., He, D., Wang, X. & Guo, Y. CdS/NH4V4O10 S-scheme photocatalyst for sustainable photo-decomposition of amoxicillin. Chem. Eng. J. 426, 130354 (2021).

Elmolla, E. S. & Chaudhuri, M. Photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin, ampicillin and cloxacillin antibiotics in aqueous solution using UV/TiO2 and UV/H2O2/TiO2 photocatalysis. Desalination 252, 46–52 (2010).

Martinez, S., Delgado, M. & Jarvis, P. Removal of Herbicide Mecoprop from surface water using advanced oxidation processes (AOPS). Int. J. Environ. Res. 10(2), 291–296 (2016).

Barzegar, G. et al. Ciprofloxacin degradation by catalytic activation of monopersulfate using Mn–Fe oxides: Performance and mineralization. Water Sci. Technol. 87, 1029–1042 (2023).

Ince, N. H. Ultrasound-assisted advanced oxidation processes for water decontamination. Ultrason. Sonochem. 40, 97–103 (2018).

Babu, S. G., Ashokkumar, M. & Neppolian, B. The role of ultrasound on advanced oxidation processes. Sonochemistry 2017, 117–148 (2017).

Tijani, J. O., Fatoba, O. O., Madzivire, G. & Petrik, L. F. A review of combined advanced oxidation technologies for the removal of organic pollutants from water. Water Air Soil Pollut. 225, 1–30 (2014).

Van Gerven, T., Mul, G., Moulijn, J. & Stankiewicz, A. A review of intensification of photocatalytic processes. Chem. Eng. Process.: Process Intensif. 46, 781–789 (2007).

Boiarkina, I., Norris, S. & Patterson, D. A. The case for the photocatalytic spinning disc reactor as a process intensification technology: Comparison to an annular reactor for the degradation of methylene blue. Chem. Eng. J. 225, 752–765 (2013).

Ali, A. M., Emanuelsson, E. A. & Patterson, D. A. Photocatalysis with nanostructured zinc oxide thin films: The relationship between morphology and photocatalytic activity under oxygen limited and oxygen rich conditions and evidence for a Mars Van Krevelen mechanism. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 97, 168–181 (2010).

Boiarkina, I., Pedron, S. & Patterson, D. A. An experimental and modelling investigation of the effect of the flow regime on the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue on a thin film coated ultraviolet irradiated spinning disc reactor. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 110, 14–24 (2011).

Wood, D., Shaw, S., Cawte, T., Shanen, E. & Van Heyst, B. An overview of photocatalyst immobilization methods for air pollution remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 391, 123490 (2020).

Shan, A. Y., Ghazi, T. I. M. & Rashid, S. A. Immobilisation of titanium dioxide onto supporting materials in heterogeneous photocatalysis: A review. Appl. Catal. A: General 389, 1–8 (2010).

Berger, T., Regmi, C., Schäfer, A. & Richards, B. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dye via atomic layer deposited TiO2 on ceramic membranes in single-pass flow-through operation. J. Membrane Sci. 604, 118015 (2020).

Ola, O. & Maroto-Valer, M. M. Review of material design and reactor engineering on TiO2 photocatalysis for CO2 reduction. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C: Photochem. Rev. 24, 16–42 (2015).

Cherkasov, N., Ibhadon, A. O. & Rebrov, E. V. Novel synthesis of thick wall coatings of titania supported Bi poisoned Pd catalysts and application in selective hydrogenation of acetylene alcohols in capillary microreactors. Lab Chip 15, 1952–1960 (2015).

Zamani, S., Rahimi, M., Ghaedi, M. & Dashtian, K. WO3/Ag/ZnO S-scheme heterostructure thin film spinning disc photoreactor for intensified photodegradation of cephalexin antibiotic. Chemosphere 307, 135812 (2022).

Dong, F., Wang, Z., Li, Y., Ho, W.-K. & Lee, S. Immobilization of polymeric g-C3N4 on structured ceramic foam for efficient visible light photocatalytic air purification with real indoor illumination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 10345–10353 (2014).

Chabane, L. et al. Effects of CuO film thickness on electrical properties of CuO/ZnO and CuO/ZnS hetero-junctions. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 40, 840–847 (2015).

Kiziltaş, H., Tekin, T. & Tekin, D. Synthesis, characterization of Fe3O4@ SiO2@ ZnO composite with a core-shell structure and evaluation of its photocatalytic activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 104160 (2020).

Shivaramu, P. D. et al. Magnetic substrate supported ZnO-CuO nanocomposite as reusable photo catalyst for the degradation of organic dye. Mater. Today: Proc. 4, 12314–12320 (2017).

Dhiman, P. et al. ZnO-based heterostructures as photocatalysts for hydrogen generation and depollution: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 1–35 (2022).

Rati, Y. et al. Visible light assisted degradation of Rhodamin B by reusable S-doped ZnO thin film photocatalyst. Opt. Mater. 135, 113370 (2023).

Nouasria, F., Selloum, D., Henni, A., Tingry, S. & Hrbac, J. Improvement of the photocatalytic performance of ZnO thin films in the UV and sunlight range by Cu doping and additional coupling with Cu2O. Ceram. Int. 48, 13283–13294 (2022).

Joorabi, F. T., Kamali, M. & Sheibani, S. Effect of aqueous inorganic anions on the photocatalytic activity of CuO–Cu2O nanocomposite on MB and MO dyes degradation. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 139, 106335 (2022).

A’srai, A. I. M. & Razali, M. H. Effect of different ratio of (CuO/TiO2) Photocatalyst on their physicochemical and photocatalytic activity for Mo degradation. Int. J. Adv. Basic Appl. Sci. 3, 859 (2022).

Nga, P. T. T., Duc, N. M., Van Minh, N. & Lien, N. H. Photocatalytic degradation of oily wastewater over ZnO-CuO/rGO photocatalyst under visible light, Vietnam. J. Chem. 60, 389–397 (2022).

Taufik, A. & Saleh, R. Synthesis of iron (II, III) oxide/zinc oxide/copper (II) oxide (Fe3O4/ZnO/CuO) nanocomposites and their photosonocatalytic property for organic dye removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 491, 27–36 (2017).

Tong, H. et al. Nano-photocatalytic materials: Possibilities and challenges. Adv. Mater. 24, 229–251 (2012).

Gao, M., Zhu, L., Ong, W. L., Wang, J. & Ho, G. W. Structural design of TiO2-based photocatalyst for H 2 production and degradation applications. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5, 4703–4726 (2015).

Wang, Y., Yang, C., Chen, A., Pu, W. & Gong, J. Influence of yolk-shell Au@ TiO2 structure induced photocatalytic activity towards gaseous pollutant degradation under visible light. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 251, 57–65 (2019).

Shi, X., Lou, Z., Zhang, P., Fujitsuka, M. & Majima, T. 3D-Array of Au–TiO2 yolk–shell as plasmonic photocatalyst boosting multi-scattering with enhanced hydrogen evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 31738–31745 (2016).

Ma, M. et al. Synthesis of yolk-shell structure Fe3O4/P (MAA-MBAA)-PPy/Au/void/TiO2 magnetic microspheres as visible light active photocatalyst for degradation of organic pollutants. J. Alloys Compd. 810, 151807 (2019).

Zamani, S., Rahimi, M. R. & Ghaedi, M. Photocatalytic degradation of penicillin v Using Bi2O3/Ag/TiO2 thin film in a spinning disc photoreactor under blue LED illumination. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2022, 895 (2022).

Zamani, S., Rahimi, M. & Ghaedi, M. Spinning disc photoreactor based visible-light-driven Ag/Ag2O/TiO2 heterojunction photocatalyst film toward the degradation of amoxicillin. J. Environ. Manage. 303, 114216 (2022).

Shi, W., Lu, D., Wang, L., Teng, F. & Zhang, J. Core–shell structured Fe 3 O 4@ SiO 2@ CdS nanoparticles with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activities. RSC Adv. 5, 106038–106043 (2015).

Do, Q. C., Kim, D.-G. & Ko, S.-O. Catalytic activity enhancement of a Fe3O4@ SiO2 yolk-shell structure for oxidative degradation of acetaminophen by decoration with copper. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 1243–1253 (2018).

Rajabi, S. K., Sohrabnezhad, S. & Ghafourian, S. Fabrication of Fe3O4@ CuO core-shell from MOF based materials and its antibacterial activity. J. Solid State Chem. 244, 160–163 (2016).

Sanati, A. M., Kamari, S. & Ghorbani, F. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of cadmium adsorption from aqueous solutions by Fe3O4@ SiO2@ APTMS core–shell magnetic nanohybrid. Surfaces Interfaces 17, 100374 (2019).

Liao, J. et al. 3D core-shell Fe3O4@ SiO2@ MoS2 composites with enhanced microwave absorption performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 604, 537–549 (2021).

Ghasemzadeh, M. A., Abdollahi-Basir, M. H. & Babaei, M. Fe3O4@ SiO2–NH2 core-shell nanocomposite as an efficient and green catalyst for the multi-component synthesis of highly substituted chromeno [2, 3-b] pyridines in aqueous ethanol media. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 8, 40–49 (2015).

Yang, Y., Liu, J., Li, X., Liu, X. & Yang, Q. Organosilane-assisted transformation from core–shell to yolk–shell nanocomposites. Chem. Mater. 23, 3676–3684 (2011).

Shi, W. et al. Synthesis of yolk–shell structured Fe3O4@ void@ CdS nanoparticles: A general and effective structure design for photo-fenton reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 20831–20838 (2016).

Hui, C. et al. Core-shell Fe3O4@ SiOanoparticles synthesized with well-dispersed hydrophilic Fe 3 O 4 seeds. Nanoscale 3, 701–705 (2011).

Ekimov, A. I., Efros, A. L. & Onushchenko, A. A. Quantum size effect in semiconductor microcrystals. Solid State Commun. 56, 921–924 (1985).

Nikmah, A., Taufiq, A. & Hidayat, A. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 012046 (IOP Publishing, 2022).

Verma, M. & Haritash, A. Photocatalytic degradation of Amoxicillin in pharmaceutical wastewater: A potential tool to manage residual antibiotics. Environ. Technol. Innov. 20, 101072 (2020).

AlAbduljabbar, F. A. et al. TiO2 nanostructured coated functionally modified and composite electrospun chitosan nanofibers membrane for efficient photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutant in wastewater. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 15, 5197–5212 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Magnetic core-shell to yolk-shell structures in palladium-catalyzed suzuki-miyaura reactions: Heterogeneous versus homogeneous nature. ChemPlusChem 81, 564–573 (2016).

Abdul-Hameed, M. H. A coated of Ca/Fe layered hydroxide onto a synthesized adsorbent from (banana peels) for removal of cadmium from simulated wastewater. Caspian J. Environ. Sci. 19, 825–827 (2021).

Desai, H. B., Kumar, A. & Tanna, A. R. Structural and magnetic properties of MgFe 2 O 4 ferrite nanoparticles synthesis through auto combustion technique. Eur. Chem. Bull 10, 186–190 (2021).

Alwared, A. I., Sulaiman, F. A., Raad, H., Al-Musawi, T. J. & Mohammed, N. A. Ability of FeNi3/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposite to degrade amoxicillin in wastewater samples in solar light-driven processes. South Afr. J. Botany 153, 195–202 (2023).

Mansor, W. & Salida, W. Enhancing and Optimising the Reaction Rate of Thin Film Photocatalysts in A Photocatalytic Spinning Disc Reactor, University of Bath (2017).

Hassani, A., Khataee, A., Karaca, S., Karaca, C. & Gholami, P. Sonocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin using synthesized TiO2 nanoparticles on montmorillonite. Ultrason. Sonochem. 35, 251–262 (2017).

Kumar, J. V. et al. Construction of SnO2/g-C3N4 an effective nanocomposite for photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin and pharmaceutical effluent. Environ. Res. 209, 112809 (2022).

Boodhoo, K. V. & Al-Hengari, S. R. Micromixing characteristics in a small-scale spinning disk reactor. Chem. Eng. Technol. 35, 1229–1237 (2012).

Jafarikojour, M., Dabir, B., Sohrabi, M. & Royaee, S. J. Application of a new immobilized impinging jet stream reactor for photocatalytic degradation of phenol: Reactor evaluation and kinetic modelling. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 364, 613–624 (2018).

Lu, Y. et al. Cu2O nanocrystals/TiO2 microspheres film on a rotating disk containing long-afterglow phosphor for enhanced round-the-clock photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 224, 239–248 (2018).

Vilardi, G., Stoller, M., Verdone, N. & Di Palma, L. Production of nano Zero Valent Iron particles by means of a spinning disk reactor. Chem. Eng. Trans. 57, 751–756 (2017).

Mirzaei, M., Dabir, B., Dadvar, M. & Jafarikojour, M. Photocatalysis of phenol using a spinning disc photoreactor immobilized with TiO2 nanoparticles: Hydrodynamic modeling and reactor optimization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 1739–1749 (2017).

Li, F., Li, X., Ao, C., Lee, S. & Hou, M. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of VOCs using Ln3+–TiO2 catalysts for indoor air purification. Chemosphere 59, 787–800 (2005).

Huang, H., Xiao, K., Zhang, T., Dong, F. & Zhang, Y. Rational design on 3D hierarchical bismuth oxyiodides via in situ self-template phase transformation and phase-junction construction for optimizing photocatalysis against diverse contaminants. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 203, 879–888 (2017).

Salimi, M. et al. A new nano-photocatalyst based on Pt and Bi co-doped TiO 2 for efficient visible-light photo degradation of amoxicillin. New J. Chem. 43, 1562–1568 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Fe@ C core–shell and Fe@ C yolk–shell particles for effective removal of 4-chlorophenol. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 3988–3994 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research study was backed up by the Iran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. The authors would like to deeply acknowledge Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran for financial supports (Grant Number: 1401-1-2-22624; Ethics code: IR.IUMS.REC.1400.856).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.F.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. A.E., M.F., M.K.: investigation, methodology, writing—review& editing. M.G., M.R.R.: methodology, writing—review & editing, supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fallahizadeh, S., Gholami, M., Rahimi, M.R. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin using a spinning disc photocatalytic reactor (SDPR) with a novel Fe3O4@void@CuO/ZnO yolk-shell thin film nanostructure. Sci Rep 13, 16185 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43437-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43437-8

This article is cited by

-

Investigation on the Real Parameters of Undoped, Bismuth-doped, and Bi-Graphene-Co-Doped CuO-ZnO Mixed Oxide Thin Films for Environmental Applications

Chemistry Africa (2026)

-

Zinc-incorporated α-Bi2O3 thin films for visible-light degradation of amoxicillin: optimization, characterization, and application to pharmaceutical wastewater

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2026)

-

Degradation of amoxicillin using CoFe2O4@three-dimensional TiO2@graphene aerogels composite: kinetic, reusability, mineralization, degradation pathway, and toxicity assessment

Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy (2025)

-

Recent Advances in ZnO-Based Nanocomposites for Amoxicillin Photocatalytic Degradation and Adsorption in Wastewater: A Review

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2025)

-

Optimization of functionalized metal-doped titania for efficient photocatalytic degradation of amoxicillin: a mechanistic study

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2025)