Abstract

The excessive release of greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide (CO2) pollution, has resulted in significant environmental problems all over the world. CO2 capture technologies offer a very effective means of combating global warming, climate change, and promoting sustainable economic growth. In this work, UiO-66-NH2 was synthesized by the novel sonochemical method in only one hour. This material was characterized through PXRD, FT-IR, FE-SEM, EDX, BET, and TGA methods. The CO2 capture potential of the presented material was investigated through the analysis of gas isotherms under varying pressure conditions, encompassing both low and high-pressure regions. Remarkably, this adsorbent manifested a notable augmentation in CO2 adsorption capacity (3.2 mmol/g), achieving an approximate enhancement of 0.9 mmol/g, when compared to conventional solvothermal techniques (2.3 mmol/g) at 25 °C and 1 bar. To accurately represent the experimental findings, three isotherm, and kinetic models were used to fit the experimental data in which the Langmuir model and the Elovich model exhibited the best fit with R2 values of 0.999 and 0.981, respectively. Isosteric heat evaluation showed values higher than 80 kJ/mol which indicates chemisorption between the adsorbent surface and the adsorbate. Furthermore, the selectivity of the adsorbent was examined using the Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST), which showed a high value of 202 towards CO2 adsorption under simulated flue gas conditions. To evaluate the durability and performance of the material over consecutive adsorption–desorption processes, cyclic tests were conducted. Interestingly, these tests demonstrated only 0.6 mmol/g capacity decrease for sonochemical UiO-66-NH2 throughout 8 consecutive cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anthropogenic CO2 emissions are closely linked to society's energy consumption and how it is provided. Global warming is primarily caused by the widespread emission of greenhouse gases and the high concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere caused by the use of fossil fuels1. Emissions of greenhouse gases have increased significantly in recent years2,3,4. Climate scientists have warned that greenhouse gas emissions are at an all-time high, resulting in unprecedented levels of global warming5,6,7,8. Since pre-industrial times, the global average temperature has increased by roughly 1.1 °C. The global temperature is projected to rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2050 over pre-industrial levels9,10. In the coming decades, climate change may lead to unprecedented natural disasters on Earth. Global efforts have been made to reduce atmospheric CO2 concentrations to meet this challenge11,12,13. Due to an increased awareness of the link between atmospheric CO2 concentrations and global warming, research activities related to CO2 capture, storage, and utilization (CSU) have increased worldwide14,15. The most common methods for absorbing CO2 are chemical absorption by amine compounds, physical absorption by solid adsorbents, and membrane separation by diffusion16,17,18. Each of these methods has its advantages and disadvantages. Despite its simplicity and wide application, chemical absorption using amine compounds has several disadvantages, including high solvent consumption, a high energy requirement, and corrosion problems19,20,21. In contrast, membrane separation can significantly reduce energy consumption for CO2 absorption, but its high cost poses serious limitations22,23. Despite this, it appears that solid compounds are the most promising method for absorbing CO224,25. In order to achieve this goal, activated carbon26,27, carbon molecular sieves (CMS)28,29, polymers, aluminophosphates (AlPOs)30,31, aluminosilicate zeolites32,33, covalent-organic frameworks (COFs)34,35, and recently, an entirely new class of porous materials, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)36,37,38 have been widely considered as alternative technologies.

MOFs are porous materials comprising metal-inorganic nodes, called secondary building units (SBUs), and connected by rigid organic linkers. In the past two decades, research in MOFs has significantly broadened the range of applications for these porous and crystalline materials due to their exceptional storage, separation, and catalytic properties39,40,41,42,43. Having a unique and tunable structure, with precise control over pore size, shape, and functionality, these materials are highly promising for a variety of applications. The high surface area of MOFs allows for a high degree of gas and molecule adsorption. As a result of this property, MOFs are particularly suitable for gas storage, separation, and purification, as well as for catalysis, drug delivery, and sensing applications44,45,46,47. Research is currently focused on the development of new MOFs with improved properties, the exploration of their potential applications, and the advancement of their practical implementation in real-life environments. Different methods can be used to synthesize MOFs, including solvothermal, hydrothermal, microwave, mechanochemical, sonochemical, and electrochemical synthesis48,49,50,51,52. The choice of the method will depend on the specific properties of the MOF to be synthesized and its intended application. Each of these methods has its advantages and disadvantages. A powerful technique for synthesizing MOFs is sonochemical synthesis53,54. In this method, high-frequency ultrasonic waves are used to induce cavitation and tiny bubbles in the solution containing the metal and organic precursors. A high temperature and pressure are generated when these bubbles collapse, resulting in the formation of MOF crystals. In comparison with other conventional methods, sonochemical synthesis can produce MOFs in a relatively short period. Ultrasonic waves can accelerate the nucleation and growth of MOFs, resulting in a faster synthesis process. Furthermore, sonochemical synthesis can produce MOFs with a narrow size distribution, which is critical for a variety of applications. In addition to its high purity and crystallinity, sonochemical synthesis can produce MOFs of high purity. Using ultrasonic waves to generate high-energy conditions can facilitate the formation of well-defined MOF structures with minimal impurities. As a whole, sonochemical synthesis is a promising method for rapid, efficient, and high-quality synthesis of MOFs, making it a valuable tool for the development of new MOFs and their applications55,56,57,58.

In this study, a new sonochemical synthesis of UiO-66-NH2 has been performed using ZrCl4, 2-aminoterephthalic acid, and N, N-dimethylformamide, and the effect of particle morphology and size on gas adsorption of CO2 has been examined. Additionally, isothermic heat analysis and evaluation of different isotherm models have been performed to evaluate the adsorption performance. Using the Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST), the selectivity of the sonochemically synthesized UiO-66-NH2 under conditions mimicking flue gas compositions has been quantified. Last but not least, cyclic performance experiments were conducted over a series of 8 repeated cycles to verify the durability and consistency of the adsorbent.

Experimental section

Material

Commercially available reagent grade chemicals were used without further purification. Zirconium (IV) chloride (ZrCl4, ≥ 99.5%), 2-amino terephthalic acid (NH2-BDC, ≥ 99.0%), and N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich Co. Ltd. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%), and absolute methanol (MeOH) were purchased by Merck Company. Deionized water (> 18 MΩ cm) was used throughout the whole experiment.

Material characterization

FT-IR spectra were obtained from Shimadzu S 8400 infrared spectrophotometers using KBr pellets with a resolution of 4 cm−1 between 4000 and 400 cm−1. An ultrasonic generator (Elma-Hans Schmidbauer GmbH & Co.KG; D-78224 Singen, Germany), operating at 60 Hz with a maximum power output of 550 W, was used for the ultrasonic irradiation. FE-SEM, and EDX elemental mapping were conducted using the Zeiss Sigma 300 equipment. TEM was carried out by Philips EM 208S. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) perusals were accomplished by STOE-STADV X-ray diffractometer with copper irradiance (Cu Kα, λ = 0.154 nm emission, 40 kV/40 mA current, and 3°/min scanning rate). N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of the synthesized samples were investigated by the BET technique (Microtrac Bel Corp Belsorp mini II). Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted by STA 504 equipment from room temperature to 700 °C in air with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1.

Material preparation

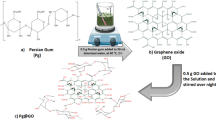

The sonochemical synthesis of the UiO-66-NH2 is such that the first 125.84 mg (0.54 mmol) of ZrCl4 was added to 5 mL of DMF, and then 1 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid was surcharged into the hybrid system to become clear under ultrasound waves. Then 135.86 mg (0.75 mmol) of 2-amino terephthalic acid was dissolved in 10 mL of DMF and appended to the prepared ZrCl4 solution. The following synthesis of the UiO-66-NH2 was carried out with ultrasonic equipment at 80 °C and atmospheric pressure for 60 min with fixed concentrations of chemical materials (Scheme 1). After centrifuging at 8000 rpm for 10 min, sediments were collected and washed three times with fresh DMF. By immersing the samples in MeOH, the DMF molecules trapped within the pores of the framework were removed by solvent exchange. The MeOH exchange process was repeated three times over three days with the solvent being refreshed every 24 h. Thereafter, UiO-66-NH2 was activated overnight under a static vacuum (50–100 mTorr) at a temperature of 100 °C.

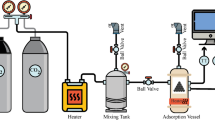

Experimental equipment

The adsorption isotherm is measured by releasing pure gases, such as CO2 or N2, from a gas storage cylinder (purity level of 99.99%). Subsequently, these gases undergo a heating process facilitated by their passage through an electric heater. Upon exiting the heater, the gases are introduced into a mixing tank, with temperature and pressure being uniform within the tank. The processed gas is then conveyed to the reactor, where it interfaces with the adsorbent material. To monitor and regulate the operational parameters, the reactor incorporates pressure and temperature sensors. The sensors facilitate the continuous measurement of gas pressure and temperature, with the acquired data being transmitted to a controlling mechanism. Through the manipulation of the heating output, the controller effectively sustains the reactor temperature at a predetermined set point. Simultaneously, a computer device logs the pressure and temperature data on a per-second basis, ensuring a comprehensive record of the process. The equations detailing the computational framework utilized for the quantification of adsorption capacity are specified as Eq. (S1–S5)59.

The precision of the fitted models concerning the empirical data was assessed through the utilization of the correlation coefficient error (R2). This metric signifies the proportion of variations observed in the reliant variable, specifically the variance within the mean. The presented equation is expressed in the subsequent manner60:

Results and discussion

Adsorbent characterization

FESEM was used to investigate the morphology and particle size of UiO-66-NH2 synthesized by the sonochemical method. The FESEM images in Fig. 1a–f show regularly shaped particles with a diameter of less than 100 nm, which is much smaller than the diameter of UiO-66-NH2 synthesized via solvothermal strategy. The UiO-66-NH2 synthesized by the sonochemical method exhibits symmetrical crystals with a sphere-shaped morphology, while UiO-66-NH2 also showed the same shape, but with larger crystals. Through the use of TEM, the exact size and morphology of the synthesized UiO-66-NH2 nanoparticles were determined. As shown in Fig. 1g, UiO-66-NH2 formed dense spherical crystals with an average size of less than 100 nm. Also, the EDX analysis of compounds showed peaks related to the Zr, C, N, and O elements Fig. 1h. Both MOFs synthesized in this study have similar crystal morphologies and EDX to those described in the literature61.

FT-IR spectra of the synthesized UiO-66-NH2 are presented in Fig. 2. In the FT-IR spectra of UiO-66-NH2 simulated (black) and synthesized by sonochemical (red) methods, the bands associated with the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of carboxylate group (COO−), in the aromatic amine group, N–H bending vibrations and C–N stretching vibrations were observed at 1568, 1629, 1386, and 1251 cm−1, respectively, which are consistent with those reported in the type of literature examined61.

The PXRD patterns of UiO-66-NH2 simulated, and the as-synthesized UiO-66-NH2 by sonochemical method, are given in Fig. 3. The characteristic peaks of the as-synthesized UiO-66-NH2, which are shown in the figure matched well with the XRD patterns previously reported (CCDC No. 889529)61,62. Sharp peaks in the XRD patterns of the sample indicate a high degree of crystallinity. The results indicate that as-synthesized UiO-66-NH2 by the sonochemical method was well prepared, and its structure is impurity-free.

PXRD patterns of the UiO-66-NH2 simulated (CCDC No. 889529)34, and the as-synthesized UiO-66-NH2 by sonochemical method.

The surface area (BET method) and pore diameter (BJH method) of UiO-66-NH2 synthesized by the sonochemical method are shown in Fig. 4. It can be observed that the structures of each sample featured the type I isotherm which has a hysteresis that indicates the presence of micropores in the material63. The BET surface area of UiO-66-NH2 synthesized by the solvothermal method was 876 m2/g with a pore volume of 0.38 cm3/g64 while the BET surface area of the UiO-66-NH2 synthesized by the sonochemical method was obtained at 993.1 m2/g with a pore volume of 0.14 cm3/g. The results showed that in the sonochemical synthesis method, not only was it synthesized in a short time (1 h) and with the easier UiO-66-NH2 method, but the surface area showed a significant increase. This advantage is very important in MOF synthesis because it optimizes the surface area. Also, the larger the surface area of the sample, the better gas adsorption occurs.

As shown in Fig. 5, TGA measurements were conducted in an air atmosphere from 40 to 750 °C to determine the thermal stability of UIO-66-NH2. The sample loses approximately 9.93% of its weight at 20–131 °C due to moisture. It has been found that weight loss is approximately 6.89 and 42.43% when the temperature is raised further, up to 275 °C and 590 °C, respectively.

UiO-66-NH2 has a chemical formula of ZrO(H2O)1/3C8H3NH2O4, according to the literature65.

The TGA results approximate the theoretical weight loss rate (%) of UiO-66-NH2 thermal decomposition according to Eq. (2).

Assessment of CO2/N2 adsorption

Experimental gas adsorption measurements

Adsorption isotherm represents a crucial curve that explains the process governing how a substance moves from porous materials or fluid environments to a solid surface at a constant temperature, either being held onto or released66,67. Adsorption equilibrium occurs when the amount of substance attached to the solid reaches a balance with the amount remaining in the solution. This equilibrium is achieved when the substance-containing phase has been in contact with the solid material for a sufficient time, resulting in a dynamic balance between the substance's concentration in the bulk solution and at the solid–fluid interface68,69. In this section, the adsorption capacity efficacy of UiO-66-NH2 MOF, fabricated using an innovative sonochemical procedure, is compared with that of the conventional solvothermal method through empirical analysis. The assessment encompasses two distinct adsorbents, conducted at a temperature of 25 °C, 50 °C, and varying pressures, to elucidate their respective isotherm characteristics. In this context, two separate pressure ranges were employed to evaluate the capacity of the adsorbents under both low and high-pressure conditions.

The adsorption capacity for CO2 of UiO-66-NH2 MOF, synthesized utilizing the sonochemical method, demonstrates a noteworthy enhancement in comparison to the conventionally synthesized UiO-66-NH2 MOF through the solvothermal approach. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the conventional UiO-66-NH2 exhibits a CO2 capacity of 2.32 mmol/g, while the sonochemically derived UiO-66-NH2 showcases an adsorption capacity of 3.2 mmol/g at 1 bar and 25 °C. This augmentation can be attributed to the higher surface area and smaller particle sizes inherent in the latter material70. The amplified surface area offers a greater number of adsorption sites available for gas molecules to interact with the surface. Consequently, this results in an elevated adsorption capacity, even under conditions of low pressure. Under elevated pressures, owing to the greater surface area afforded by the sonochemically synthesized UiO-66-NH2, it was foreseeable that this particular adsorbent would demonstrate an augmented capacity for CO2 gas molecules, as discernible from the findings presented in Fig. S1. The conventional UiO-66-NH2 registers a CO2 adsorption capacity of 14.72 mmol/g, whereas the sonochemical counterpart, UiO-66-NH2, showcases a capacity of 18.05 mmol/g under conditions of 20 bar and 25 °C. The noteworthy improvement in CO2 adsorption capacity demonstrated here enhances the promise of the novel sonochemical method employed in this study.

Isotherm modeling

Isotherm relationship is expressed mathematically, which plays a significant role in modeling, analyzing, designing, and practicing adsorption systems. This relationship is commonly visualized by graphing the amount of substance on the solid surface against the remaining concentration in the solution71. The physical and chemical properties of the system, along with the underlying thermodynamic assumptions, offer insights into the mechanism of adsorption, the characteristics of the surface, and how strongly the solid material attracts the substance72.

The Langmuir adsorption isotherm was initially formulated to elucidate gas-to-solid phase adsorption phenomena; subsequently, its applicability extended to encompass solid–liquid interfaces. The degree of surface coverage is expressed in terms of fractional coverage and is contingent upon the concentration of the adsorbate. The mathematical derivation is predicated upon the inherent conceptual simplicity of the underlying mechanisms, in conjunction with several presumptions: (1) uniform homogeneity across the surface, indicating energetically homogeneous sites; (2) adsorption transpires as a monomolecular layer process, with each site exclusively accommodating a solitary adsorbate molecule; (3) absence of lateral interactions among adsorbed molecules; and (4) the reversibility of the adsorption process73 (Eq. 3).

The Freundlich isotherm possesses the capacity to delineate non-ideal, multilayer, and reversible adsorption transpiring at a heterogeneous surface. This isotherm additionally postulates the existence of diverse binding energies among the adsorption sites. The energy distribution encompassing adsorptive sites, as delineated within the framework of the Freundlich isotherm, manifests as a spectrum of varying binding energies, rather than a uniform energy distribution. This distribution adheres to an exponential-type function, closely approximating the complexities of actual adsorption scenarios74 (Eq. 4).

The Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm represents an empirical framework originally devised to elucidate the adsorption behavior of subcritical vapors onto micropore solids through a pore-filling mechanism. Typically, it finds application in characterizing adsorption processes involving a Gaussian energy distribution on heterogeneous surfaces75 (Eqs. 5, 6).

The variables qe and qm denote the equilibrium quantity and the maximum capacity of adsorption for CO2 and N2 gases (expressed in mmol/g). The parameter Pe represents the pressure prevailing during the equilibrium state (measured in bar). The Freundlich model is characterized by the constants KF (mmol/g.bar^1/n) and n, while the Langmuir model is defined by the constant KL. Within the Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) model, the symbol β signifies a model-specific constant (quantified in mol2/J), while the term ω pertains to the Polanyi potential (measured in J/mol) and E (kJ/mol) represents the average energy of sorption when it moves from the bulk solution to the solid surface76. The graphical depiction of the pertinent fitting models can be observed in Fig. S2, within the context of a stable temperature environment set at 25 °C.

Fitting values of isotherm models with their respective R2 values at 25 °C are reported in Table 1. Drawing from an assessment of the average coefficients of determination (R2) obtained from diverse isotherm models, it becomes evident that the Langmuir model exhibits a higher degree of precision when compared to alternative models. This alignment with existing scholarly literature is noteworthy, as the preponderance of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) predominantly rely upon the Langmuir isotherm model to illuminate their behavioral characteristics77. Based on the content expounded within this section, it can be compellingly inferred that the phenomenon of monolayer adsorption onto the surface of MOFs is indeed transpiring. Furthermore, a notable consequence of this study's findings pertains to the discernment of an absence of lateral interactions among the adsorbed species. Moreover, it is intimated that the suitability to reversibility inherent in this adsorption process surmounts the comparably intricate dynamics intrinsic to alternative adsorption mechanisms78.

Adsorption kinetic evaluation

The rate of adsorption is additionally regulated by adsorption kinetics, playing a pivotal role in dictating the temporal extent essential for achieving adsorption equilibrium. Kinetic models offer insights into the trajectories of adsorption and the potential mechanisms at play. This data holds significance in the advancement of the process and the design of the adsorption system79.

The pseudo-first-order model operates under the premise that the rate of change of solute adsorption over time is directly correlated to the disparity between saturation concentrations and the quantity of solid adsorption as time progresses. This principle is generally valid during the initial phases of an adsorption procedure (Eq. (7))80.

The theoretical framework of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model rests upon the supposition that the governing factor in the rate of adsorption is the process of chemical sorption or chemisorption. This model offers projections encompassing the entirety of adsorption dynamics. In this scenario, the pace of adsorption is determined by the capacity for adsorption, rather than being influenced by the concentration of the adsorbate (Eq. 8)81.

The elovich kinetic model finds frequent application in the interpretation of adsorption kinetics and effectively characterizes second-order kinetics, under the premise that the surface exhibits energetic heterogeneity (Eq. 9)82.

Here, qt, K1, and K2 denote the adsorption capacity, the rate constant for the pseudo-first-order model, and the rate constant for the pseudo-second-order model, respectively. Within the framework of the Elovich model, the parameter "α" signifies the initial rate of adsorption (mg/g.min), while the parameter "β" represents the constant associated with the desorption process (g/mg).

Based on the observations presented in Table 2 and the correlation coefficient (R2) values associated with the kinetic models, the Elovich model may be selected as the most suitable model. Drawing from the parameters derived via the Elovich kinetic model, it becomes evident that the initial adsorption rate stands impressively at 22.72 mg/g∙min. This particular value carries significance within the CO2 capture domain due to its substantial nature. Simultaneously, the desorption constant, fixed at 2.408 g/mg, emerges as notably high. This elevated desorption constant introduces a challenge when it comes to facilitating the desorption process—a less favorable aspect for integrating energy in industrial processes. Higher desorption constants contribute to a more complicated desorption phase, making it tougher to release adsorbed molecules smoothly. This poses a hitch in terms of energy efficiency and overall integration of industrial operations. On the other side, lower values of this parameter indicate that the adsorbent material isn't very inclined to hold onto adsorbate molecules. This might seem advantageous for facilitating desorption, but it could also affect the effectiveness of the adsorption process itself. The kinetic models employed in this study and their corresponding fittings are illustrated in Fig. 7.

Isosteric heat of adsorption

In the realm of thermodynamic attributes, a preeminent parameter employed to assess the extent of interaction between CO2 molecules and the surfaces of adsorbents pertains to the isosteric heat of adsorption. This parameter plays a pivotal role in the formulation and advancement of gas separation methodologies of notable industrial significance, such as pressure-swing adsorption (PSA) and temperature-swing adsorption (TSA)83. This bears substantial significance in the realm of industrial gas separation processes. The significance of the isosteric heat of adsorption (Qst) magnitude lies in its ability to delineate the interplay between the adsorbent and the adsorbate species. This metric serves as a descriptor for the robustness of the adsorption phenomenon, with an escalated Qst denoting a more pronounced interaction between the adsorbed substance and the adsorbing material. Notably, an elevated Qst value corresponds to intensified bonding between the adsorbate and the adsorbent, albeit accompanied by a concomitant escalation in regeneration expenses. The quantification of the isosteric heat of adsorption finds its mathematical expression in the Clausius–Clapeyron equation as follows84:

Herein, Qst represents the isosteric heat of adsorption at a constant level of adsorbed quantity denoted as n [mmol/g], while R stands for the universal gas constant [J/mol⋅K]. As depicted in Fig. 8, the initial heat of adsorption registers a value exceeding 80 kJ/mol, serving as an indicative marker of chemisorption events transpiring at the surface of the Metal–Organic Framework (MOF)85. This notable energy association between the adsorbate and the adsorbent comes from the presence of amine functional groups inherent within the structural framework of UiO-66-NH2. As the dynamic process of adsorption advances at the interface, the isosteric heat experiences a proportionate decline, primarily attributed to the progressive occupation of adsorption sites and the concomitant reduction in available surface domains for the adhesion of adsorbate entities. This phenomenon is intricately intertwined with the evolving interplay between the adsorbent surface and the adsorbate molecules. Additionally, the low isosteric heat value for nitrogen adsorption aligns with the low adsorption amount observed. This could be due to nitrogen molecules having weak electrostatic interactions with the adsorbent surface.

IAST-based selectivity

Upon its initial inception by Myers and Prausnitz86, the IAST methodology was conceived. This theoretical framework mandates the availability of distinct single-component isotherms corresponding to each gas species. This prerequisite facilitates the prognostication of both selectivity and adsorption behaviors for every constituent present within a mixture comprising the aforementioned gas species. In scenarios featuring a binary mixture, a set of four equations (Eq. S6–S9) necessitates resolution in order to derive values for \({P}_{B}^{*}\) and \({P}_{C}^{*}\). The successful resolution of this equation set is imperative for attaining a comprehensive grasp of the compositional attributes characterizing the system87.

In the present section, an assessment of selectivity was conducted through the utilization of Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST) calculations. These calculations were performed under the representative gas composition of flue gases, comprised of 15% CO2 and 85% N288 As delineated in Fig. 9, the sonochemical variant of UiO-66-NH2 demonstrates a notable preference for CO2, particularly observable at an operating pressure of 1 bar. The discernible and quantifiable escalation in the degree of selectivity, conspicuously coincident with a progressively augmented operational pressure, can be expounded upon in the context of an expanded reservoir of CO2 molecules, thereby affording an increased propensity for intricate and selective interactions with the functional amine groups. This intriguing phenomenon, which inherently governs the distinctive predilection for CO2 adsorption, finds its theoretical foundation in the underlying non-reactive attributes inherent to N2 molecules, compelling them to exhibit limited affinity for engagement with the said amine groups89, The selective molecular dynamics underscored by this intriguing behavior can be further rationalized by invoking the broader intermolecular forces at play. Specifically, the notable exclusion of N2 molecules from active participation in adsorptive processes can be attributed to the distinct electronic and steric attributes inherent to these molecules, rendering them less inclined to form robust and chemically meaningful interactions with the amine functionalities. This, in turn, perpetuates the prevailing selectivity bias towards CO2. In this intricate molecular interplay, the intricate framework of attractive and repulsive forces governing the interactions between nitrogen species comes into play. The intrinsic repulsive forces operative between nitrogen molecules provide an additional facet to the observed selectivity enhancement. The repulsion that manifests when nitrogen molecules approach each other discourages their aggregation, further segregating them from the more favored CO2 molecules that are amenable to productive interaction with the functional groups90.

Adsorption mechanism

The principal mechanism governing the adsorption of CO2 and N2 molecules onto UiO-66-NH2 involves their chemisorption onto the amine functional groups located on the surface. In the context of this chemical reaction, the amine species (RNH2) undergoes a reaction with carbon dioxide (CO2), resulting in the generation of an amine carbamate substance (RNHCOO−)91. In the context of physisorption, benzene rings exhibit resonance structures that produce a state of delocalized electron density within the ring structure92. This phenomenon leads to the accumulation of heightened negative charges at the center of the benzene rings, thereby giving rise to an elevated field gradient. In our scenario, where both adsorbates possess different quadrupole moments, the comprehensive interaction between a homogeneous electric field and the quadrupole yielded zero. Nevertheless, a significant interaction proceeds between the quadrupole and the gradient of the electric field. Consequently, the electrostatic interaction provokes the adsorption of CO2 molecules by the benzene rings, with certain N2 molecules adsorbed onto the peripheral regions of these benzene rings. All this information is visually depicted in Scheme 2, wherein the black boxes exemplify the phenomenon of chemisorption, the blue box signifies the electrostatic interaction of CO2 molecules situated at the center of benzene rings, and the green box illustrates the adsorption of N2 molecules on the outer peripheries of the benzene rings.

Cyclic stability of adsorbent

The assessment of an adsorbent's stability and regenerability holds significant importance in the evaluation of its appropriateness for CO2 capture procedures1. In order to gauge the reusability of sonochemical UiO-66-NH2, a sequence comprising 8 adsorption cycles was executed under conditions of 25 °C and 1 bar. After this, the adsorbents underwent recycling via exposure to a vacuum oven at a temperature of 150 °C for a duration of 8 h. The findings, depicted in Fig. S3, underscore the remarkable stability exhibited by sonochemical UiO-66-NH2 throughout the span of the eight cycles compared to solvothermal UiO-66-NH2. The cyclic examinations reveal a negligible reduction in CO2 capacity for the adsorbents, indicating a mere 0.6 mmol/g decline for sonochemical UiO-66-NH2 and 0.58 mmol/g decrease for solvothermal UiO-66-NH2. This great stability can be ascribed to the presence of amine groups that are grafted in the structure, in conjunction with the small particle dimensions. This observation underscores the prowess of sonochemical UiO-66-NH2 as a highly promising contender for the CO2 capture process, given its capacity to sustain a noteworthy level of CO2 adsorption even after undergoing 8 consecutive cycles. In sum, the exceptional stability and regenerability demonstrated by the adsorbent, combined with its elevated CO2 capacity and much shorter synthesis time, establish it as a propitious choice for applications in CO2 capture.

Conclusions

Through experimental adsorption measurements, our investigation reveals a marked enhancement in CO2 adsorption exhibited by sonochemical UiO-66-NH2, in comparison to its solvothermal UiO-66-NH2 counterpart. This augmentation can be attributed to the increased surface area and smaller particle sizes characteristic of the sonochemically synthesized material. Employing isotherm modeling techniques, our analysis identifies the Langmuir isotherm as the optimal fit for the empirical data. This alignment suggests monolayer adsorption behavior, underscoring the prevalent influence of chemisorption phenomena. The application of kinetic modeling analysis yielded the Elovich model as the most appropriate fitting function, thereby emphasizing the significance of the chemisorption phenomenon. The isosteric heat analysis manifests substantial energies associated with the interaction between the adsorbent's surface and CO2 molecules. This observation provides further corroboration for the occurrence of chemical reactions involving the amine groups and CO2 gas. Utilizing the Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory (IAST), we quantify the selectivity of the adsorbent and ascertain its notable affinity for CO2 under flue gas conditions, primarily attributable to the presence of amine functional groups. Additionally, an evaluation of the cyclic performance of the adsorbent underscores its viability over successive operational cycles. Specifically, the sonochemical UiO-66-NH2 material exhibits satisfactory stability over 8 cycles, albeit with a reduction in capacity linked to the gradual degradation of the amine groups and their interaction with CO2 molecules. In conclusion, the sonochemical synthesis route for UiO-66-NH2, characterized by augmented surface area and smaller particle sizes achievable within a concise one-hour period, produces a substantial elevation in CO2 adsorption capacity. Moreover, the material demonstrates pronounced selectivity for CO2 under flue gas conditions, ascribed to the strategic integration of amine functional groups. These findings collectively highlight the promising attributes of sonochemical UiO-66-NH2 as a potential candidate for advanced CO2 capture applications.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Adsorption capacity calculation equations, IAST calculation equations, CO2 adsorption capacity at high pressures, Isotherm model fitting plots, cyclic performance of adsorbent. This material is available free of charge from http://pubs.acs.org.

References

Bahmanzadegan, F., Pordsari, M. A. & Ghaemi, A. Improving the efficiency of 4A-zeolite synthesized from kaolin by amine functionalization for CO2 capture. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 12533 (2023).

Usman, M. et al. How do financial development, energy consumption, natural resources, and globalization affect Arctic countries’ economic growth and environmental quality? An advanced panel data simulation. Energy 241, 122515 (2022).

Hu, X. E. et al. A review of N-functionalized solid adsorbents for post-combustion CO2 capture. Appl. Energy 260, 114244 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Low-cost DETA impregnation of acid-activated sepiolite for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 353, 940–948 (2018).

Holechek, J. L. et al. A global assessment: can renewable energy replace fossil fuels by 2050?. Sustainability 14(8), 4792 (2022).

Saleh, T. A. Nanomaterials and hybrid nanocomposites for CO2 capture and utilization: Environmental and energy sustainability. RSC advances 12(37), 23869–23888 (2022).

Gillett, N. P. et al. Constraining human contributions to observed warming since the pre-industrial period. Nat. Clim. Change 11(3), 207–212 (2021).

Zhang, G. et al. Low-price MnO2 loaded sepiolite for Cd2+ capture. Adsorption 25, 1271–1283 (2019).

Zhao, G. et al. Energy system transformations and carbon emission mitigation for China to achieve global 2 C climate target. J. Environ. Manag. 292, 112721 (2021).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 °C. Science 365(6459), eaaw6974 (2019).

Raganati, F., Miccio, F. & Ammendola, P. Adsorption of carbon dioxide for post-combustion capture: A review. Energy Fuels 35(16), 12845–12868 (2021).

Kandy, M. M. Carbon-based photocatalysts for enhanced photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to solar fuels. Sustain. Energy Fuels 4(2), 469–484 (2020).

Yamada, H. Amine-based capture of CO2 for utilization and storage. Polym. J. 53(1), 93–102 (2021).

Chatterjee, S. & Huang, K.-W. Unrealistic energy and materials requirement for direct air capture in deep mitigation pathways. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 3287 (2020).

Pandey, A. et al. Experimental investigation on the effect of reservoir conditions on stability and rheology of carbon dioxide foams of nonionic surfactant and polymer: Implications of carbon geo-storage. Energy 235, 121445 (2021).

Zahedi, R., Ayazi, M. & Aslani, A. Comparison of amine adsorbents and strong hydroxides soluble for direct air CO2 capture by life cycle assessment method. Environ. Technol. Innov. 28, 102854 (2022).

Ochedi, F. O. et al. Carbon dioxide capture using liquid absorption methods: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 19, 77–109 (2021).

Pashaei, H., Mashhadimoslem, H. & Ghaemi, A. Modeling, and optimization of CO2 mass transfer flux into Pz-KOH-CO2 system using RSM and ANN. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 4011 (2023).

Gautam, A. & Mondal, M. K. Review of recent trends and various techniques for CO2 capture: Special emphasis on biphasic amine solvents. Fuel 334, 126616 (2023).

Sang Sefidi, V. & Luis, P. Advanced amino acid-based technologies for CO2 capture: A review. Indus. Eng. Chem. Res. 58(44), 20181–20194 (2019).

Hu, X. et al. Low-cost novel silica@ polyacrylamide composites: Fabrication, characterization, and adsorption behavior for cadmium ion in aqueous solution. Adsorption 26, 1051–1062 (2020).

Kim, S. et al. Gas–liquid membrane contactors for carbon dioxide separation: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 411, 128468 (2021).

Odunlami, O. et al. Advanced techniques for the capturing and separation of CO2—A review. Results Eng. 15, 100512 (2022).

Keshavarz, L. et al. A comprehensive review on the application of aerogels in CO2-adsorption: Materials and characterization. Chem. Eng. J. 412, 128604 (2021).

Zheng, J. et al. Carbon dioxide sequestration via gas hydrates: A potential pathway toward decarbonization. Energy Fuels 34(9), 10529–10546 (2020).

Gopalan, J., Buthiyappan, A. & Raman, A. A. A. Insight into metal-impregnated biomass-based activated carbon for enhanced carbon dioxide adsorption: A review. J. Indus. Eng. Chem. 113, 72–95 (2022).

Serafin, J. & Cruz, O. F. Jr. Promising activated carbons derived from common oak leaves and their application in CO2 storage. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10(3), 107642 (2022).

Ghaemi, A., Dehnavi, M.K. & Khoshraftar, Z. Exploring artificial neural network approach and RSM modeling in the prediction of CO2 capture using carbon molecular sieves. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 7, 00310 (2023).

Mukti, N. I. F. et al. Efficacy of modified carbon molecular sieve with iron oxides or choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvent for the separation of CO2/CH4. RSC Adv. 13(33), 23158–23168 (2023).

Anbealagan, L. et al. Mixed matrix membranes incorporated with zeolite AlPO-18 for CO2/CH4 separation. In Materials Today: Proceedings (2023).

Imtiaz, A. et al. ZIF-filler incorporated mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) for efficient gas separation: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 108541 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Achieving highly selective CO2 adsorption on SAPO-35 zeolites by template-modulating the framework silicon content. Chem. Sci. 13(19), 5687–5692 (2022).

Secci, F. et al. On the role of the nature and density of acid sites on mesostructured aluminosilicates dehydration catalysts for dimethyl ether production from CO2. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11(3), 110018 (2023).

Lyu, H. et al. Covalent organic frameworks for carbon dioxide capture from air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144(28), 12989–12995 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Covalent organic frameworks for CO2 capture: From laboratory curiosity to industry implementation. Chem. Soc. Rev. (2023).

Li, L. et al. Review on applications of metal–organic frameworks for CO2 capture and the performance enhancement mechanisms. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 162, 112441 (2022).

Gaikwad, S. & Han, S. Shaping metal-organic framework (MOF) with activated carbon and silica powder materials for CO2 capture. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11(2), 109593 (2023).

Esfahani, H.J., Shahhosseini, S. & Ghaemi, A. Improved Structure of Zr-BTC Metal-Organic Framework Using NH2 to Enhance CO2 Adsorption Performance. (2023).

Zhai, X., Cui, Z. & Shen, W. Mechanism, structural design, modulation and applications of aggregation-induced emission-based metal-organic framework. Inorgan. Chem. Commun. 5, 110038 (2022).

Zou, Y. H. et al. Porous metal–organic framework liquids for enhanced CO2 adsorption and catalytic conversion. Angew. Chem. 133(38), 21083–21088 (2021).

Ghanbari, T., Abnisa, F. & Daud, W. M. A. W. A review on the production of metal-organic frameworks (MOF) for CO2 adsorption. Sci. Total Environ. 707, 135090 (2020).

Ramezanalizadeh, H. & Manteghi, F. Synthesis of a novel MOF/CuWO4 heterostructure for efficient photocatalytic degradation and removal of water pollutants. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 2655–2666 (2018).

Ramezanalizadeh, H. & Manteghi, F. Mixed cobalt/nickel metal–organic framework, an efficient catalyst for one-pot synthesis of substituted imidazoles. Monatsh. Chem.-Chem. Mon. 148, 347–355 (2017).

Shahini, M. et al. Recent innovations in synthesis/characterization of advanced nanoporous metal-organic frameworks (MOFs); Current/future trends with a focus on the smart anti-corrosion features. Mater. Chem. Phys. 276, 125420 (2022).

Mallakpour, S., Nikkhoo, E. & Hussain, C. M. Application of MOF materials as drug delivery systems for cancer therapy and dermal treatment. Coord. Chem. Rev. 451, 214262 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Tin-based metal-organic framework catalysts for high-efficiency electrocatalytic CO2 conversion into formate. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 626, 836–847 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Exfoliation of metal-organic framework nanosheets using surface acoustic waves. Ultrason. Sonochem. 83, 105943 (2022).

Huang, C.-W. et al. Metal–organic frameworks: Preparation and applications in highly efficient heterogeneous photocatalysis. Sustain. Energy Fuels 4(2), 504–521 (2020).

Moharramnejad, M. et al. MOF as nanoscale drug delivery devices: Synthesis and recent progress in biomedical applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 3, 104285 (2023).

Kaur, H. et al. Metal-organic framework-based materials for wastewater treatment: Superior adsorbent materials for the removal of hazardous pollutants. ACS omega 8(10), 9004–9030 (2023).

Issaka, E. et al. Zinc imidazolate metal–organic frameworks-8-encapsulated enzymes/nano enzymes for biocatalytic and biomedical applications. Catal. Lett. 153(7), 2083–2106 (2023).

Ramezanalizadeh, H., Zakeri, F. & Manteghi, F. Immobilization of BaWO4 nanostructures on a MOF-199-NH2: An efficient separable photocatalyst for the degradation of organic dyes. Optik 174, 776–786 (2018).

Taghipour, A. et al. Ultrasonically synthesized MOFs for modification of polymeric membranes: A critical review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 12, 106202 (2022).

Tahir, M. et al. MOF-based composites with engineering aspects and morphological developments for photocatalytic CO2 reduction and hydrogen production: A comprehensive review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4, 109408 (2023).

Vaitsis, C., Sourkouni, G. & Argirusis, C. Sonochemical synthesis of MOFs. In Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications 223–244 (Elsevier, 2020).

Lin, G. et al. A systematic review of metal organic frameworks materials for heavy metal removal: Synthesis, applications and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 460, 141710 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Sonochemical preparation of inorganic nanoparticles and nanocomposites for drug release—A review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60(28), 10011–10032 (2021).

Korayem, A. K., Ghamami, S. & Bahrami, Z. Fractal properties and morphological investigation of nano-amiodarone using image processing. Signal Image Video Process. 13(2), 281–287 (2019).

RamezanipourPenchah, H., Ghaemi, A. & Ganadzadeh Gilani, H. Benzene-based hyper-cross-linked polymer with enhanced adsorption capacity for CO2 capture. Energy Fuels 33(12), 12578–12586 (2019).

Mashhadimoslem, H. et al. Adsorption equilibrium, thermodynamic, and kinetic study of O2/N2/CO2 on functionalized granular activated carbon. ACS Omega 7(22), 18409–18426 (2022).

Fang, Y. et al. Highly selective visible-light photocatalytic benzene hydroxylation to phenol using a new heterogeneous photocatalyst UiO-66-NH 2-SA-V. Catal. Lett. 149, 2408–2414 (2019).

Jung, H. et al. Characterization of the zirconium metal-organic framework (MOF) UiO-66-NH2 for the decomposition of nerve agents in solid-state conditions using phosphorus-31 solid state-magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (31P SS-MAS NMR) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Anal. Lett. 54(3), 468–480 (2021).

Zhao, F. et al. In-situ growth of UiO-66-NH2 onto polyacrylamide-grafted nonwoven fabric for highly efficient Pb (II) removal. Appl. Surf. Sci. 527, 146862 (2020).

Luu, C. L. et al. Synthesis, characterization and adsorption ability of UiO-66-NH2. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 6(2), 025004 (2015).

Valenzano, L. et al. Disclosing the complex structure of UiO-66 metal organic framework: A synergic combination of experiment and theory. Chem. Mater. 23(7), 1700–1718 (2011).

Limousin, G. et al. Sorption isotherms: A review on physical bases, modeling and measurement. Appl. Geochem. 22(2), 249–275 (2007).

Allen, S., Mckay, G. & Porter, J. F. Adsorption isotherm models for basic dye adsorption by peat in single and binary component systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 280(2), 322–333 (2004).

Kumar, K. V. & Sivanesan, S. Sorption isotherm for safranin onto rice husk: Comparison of linear and non-linear methods. Dyes Pigments 72(1), 130–133 (2007).

Ghiaci, M. et al. Equilibrium isotherm studies for the sorption of benzene, toluene, and phenol onto organo-zeolites and as-synthesized MCM-41. Sep. Purif. Technol. 40(3), 217–229 (2004).

Al-Degs, Y. S. et al. Effect of surface area, micropores, secondary micropores, and mesopores volumes of activated carbons on reactive dyes adsorption from solution. Sep. Sci. Technol. 39(1), 97–111 (2005).

Ncibi, M. C. Applicability of some statistical tools to predict optimum adsorption isotherm after linear and non-linear regression analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 153(1–2), 207–212 (2008).

Bulut, E., Özacar, M. & Şengil, İA. Adsorption of malachite green onto bentonite: Equilibrium and kinetic studies and process design. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 115(3), 234–246 (2008).

Ghosal, P. S. & Gupta, A. K. Determination of thermodynamic parameters from Langmuir isotherm constant-revisited. J. Mol. Liq. 225, 137–146 (2017).

Skopp, J. Derivation of the Freundlich adsorption isotherm from kinetics. J. Chem. Educ. 86(11), 1341 (2009).

Hu, Q. & Zhang, Z. Application of Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model at the solid/solution interface: A theoretical analysis. J. Mol. Liq. 277, 646–648 (2019).

Taheri, F. S., Ghaemi, A. & Maleki, A. High efficiency and eco-friendly TEPA-functionalized adsorbent with enhanced porosity for CO2 capture. Energy Fuels 33(11), 11465–11476 (2019).

Huang, A., Wan, L. & Caro, J. Microwave-assisted synthesis of well-shaped UiO-66-NH2 with high CO2 adsorption capacity. Mater. Res. Bull. 98, 308–313 (2018).

Do, D.D. Adsorption Analysis: Equilibria and Kinetics (With CD Containing Computer MATLAB Programs). Vol. 2. (World Scientific, 1998).

Masoumi, H., Ghaemi, A. & Gilani, H. G. Synthesis of polystyrene-based hyper-cross-linked polymers for Cd (II) ions removal from aqueous solutions: Experimental and RSM modeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 125923 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Experimental and kinetic analysis of H2O on HgO removal by sorbent traps in oxy-combustion atmosphere. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60(33), 12200–12209 (2021).

Taheri, F. S. et al. High CO2 adsorption on amine-functionalized improved mesoporous silica nanotube as an eco-friendly nanocomposite. Energy Fuels 33(6), 5384–5397 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Kinetics and mechanism study of mercury adsorption by activated carbon in wet oxy-fuel conditions. Energy Fuels 33(2), 1344–1353 (2019).

Raganati, F., Chirone, R. & Ammendola, P. CO2 capture by temperature swing adsorption: Working capacity as affected by temperature and CO2 partial pressure. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59(8), 3593–3605 (2020).

Abdulsalam, J. et al. Equilibria and isosteric heat of adsorption of methane on activated carbons derived from South African coal discards. ACS Omega 5(50), 32530–32539 (2020).

Ammendola, P., Raganati, F. & Chirone, R. CO2 adsorption on a fine activated carbon in a sound assisted fluidized bed: Thermodynamics and kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 322, 302–313 (2017).

Myers, A. L. & Prausnitz, J. M. Thermodynamics of mixed-gas adsorption. AIChE J. 11(1), 121–127 (1965).

Ismail, M. et al. Ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) of carbon dioxide and methane adsorption using magnesium gallate metal-organic framework (Mg-gallate). Molecules 28(7), 3016 (2023).

Yan, H. et al. A green synthesis strategy for low-cost multi-porous solid CO2 adsorbent using blast furnace slag. Fuel 329, 125380 (2022).

Chen, C., Kim, J. & Ahn, W.-S. CO2 capture by amine-functionalized nanoporous materials: A review. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 31, 1919–1934 (2014).

Darunte, L. A. et al. CO2 capture via adsorption in amine-functionalized sorbents. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 12, 82–90 (2016).

Said, R. B. et al. A unified approach to CO2–amine reaction mechanisms. ACS Omega 5(40), 26125–26133 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Global aromaticity in macrocyclic polyradicaloids: Huckel’s rule or baird’s rule?. Acc. Chem. Res. 52(8), 2309–2321 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes out to the Iran University of Science and Technology (IUST) for providing us with some facilities and materials. In this study, no specific grants were received from public, commercial, or non-profit funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Sofware, Conceived and designed the experiments, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing-review & editing. F.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing-review & editing. M.A.P.: Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing-review & editing. F.M.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Conceived and designed the experiments, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, and Writing-original draft. A.T.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Conceived and designed the experiments, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing-review & editing. A.G.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Conceived and designed the experiments, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, and Writing-original draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kazemi, A., Moghadaskhou, F., Pordsari, M.A. et al. Enhanced CO2 capture potential of UiO-66-NH2 synthesized by sonochemical method: experimental findings and performance evaluation. Sci Rep 13, 19891 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47221-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47221-6

This article is cited by

-

PSYMOF: computational workflow enabling systematic post-synthesis modification of metal-organic frameworks

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

MOF UiO-66 and its composites: design strategies and applications in drug and antibiotic removal

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2025)

-

Electrochemical Sensing of Quinoline and Pyridine Utilizing Reusable Graphene-Zirconium Metal-Organic Framework Hybrids on Glassy Carbon Electrodes

Chemistry Africa (2025)

-

A multi-functional composite nanocatalyst for the synthesis of biologically active pyrazolopyranopyrimidines: Multifaceted antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities

Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials (2025)

-

Recovery of Au(III) from electronic waste using solid phase extraction based on a magnetic nanobiocomposite, OCBs@Fe3O4@UiO-66-SH

Microchimica Acta (2025)