Abstract

Host (base) fluids are unable to deliver efficient heating and cooling processes in industrial applications due to their limited heat transfer rates. Nanofluids, owing to their distinctive and adaptable thermo-physical characteristics, find a widespread range of practical applications in various disciplines of nanotechnology and heat transfer equipment. The novel effect of this study is to determine the effects of mixed convection, and activation energy on 3D Sutterby nanofluid across a bi-directional extended surface under the impact of thermophoresis diffusion and convective heat dissipation. The flow equations are simplified in terms of partial differential equations (PDEs) and altered to non-dimensional ODEs by implementing classical scaling invariants. Numerical results have been obtained via the bvp4c approach. The physical insights of crucial and relevant parameters on flow and energy profiles are analysed through plotted visuals. Some factors have multiple solutions due to shrinking sheets. So stability analysis has been adapted to analyses stable solutions. Graphical representations demonstrate the reliability and accuracy of the numerical algorithm across a variety of pertinent parameters and conditions. A comparison between existing results and previously published data shows a high degree of compatibility between the two datasets. The present study extensively explored a multitude of practical applications across a diverse spectrum of fields, including but not limited to gas turbine technology, power generation, glass manufacturing, polymer production, wire coating, chemical production, heat exchangers, geothermal engineering, and food processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In contrast to Newtonian fluids, which exhibit consistent viscosity regardless of shear stress, non-Newtonian fluids (NNFs) are distinguished by their viscosity varying due to shear stress. A prominent example of a NNF is the Maxwell fluid, extensively utilized for modeling the rheological characteristics of complex fluids like polymer, delays, and suspensions1. Rendering to this theoretical framework, a NNF comprises elastic as well as viscous module. The academic has exhibited significant concentration in comprehending the behaviour of NNFs, as they find applications through a broad variety of domains, comprising genetic solutions and engineering processes. The term NF flow pertains to the motion of a fluid containing deferred nano-molecules, which occurs as a response to an external pressure gradient. The inclusion of nanoparticles can lead to substantial modifications in the fluid's characteristics, such as viscosity and thermal conductivity, ultimately giving rise to complex and frequently non-conventional fluid behavior2. Buongiorno’s model3 has served as a foundational framework for the examination of heat transmission improvements in NFs. Within this context, it has been established that thermophoresis and random diffusion play pivotal roles, among other influencing factors. Prasad et al.4 have exemplified the behavior of radiative nanomaterial flow underneath the inspiration of the Lorentz force. Tian et al.5 have explored the thermal analysis of convectively heated MHD nanoliquid flow. Hayat et al.6 have shed light on the thermal transmission effects in convective HNFF, with a specific focus on the impact of radiation. Ahmad et al.7 have delved into the study of heat transmission in Maxwell nanomaterial flow exposed to a rotating porous medium. Meanwhile, Khan et al.8 have contributed insights into the entropy aspects of Carreau nanomaterial flow. Chu et al.9 have described results on the thermal properties of nanofluids incorporating viscoelastic materials, providing valuable insights into the field of thermal determination in such materials. Adnan et al.10 have documented their investigation into the Riga surface flow as a means of evaluating the thermal freeze valuation of NFs. Ibrahim et al.11 have established links related to neural networks in the context of NF-related model. Akbar and Khan12 have presented their work on the flow of ciliated nanofluids, taking into account the effects of viscoelastic heating. Khan et al.13 have provided insights into the multiple diffusion impact of NFs in the context of flat plate channel. In a related study, Khan et al.14 have utilized finite element method (FEM) simulations to deduce information regarding the interaction of nanoparticles in a Y-shaped obstacle. Sharma et al.15 have directed their research towards assessing entropy generation within Couette nanofluid flow. Additionally, Sharma et al.16 have observed the impact of heat and entropy generations on channel flows.

Non-Newtonian fluids are frequently favored over viscous fluids in a variety of technological and industrial contexts. These fluids, owing to their diverse characteristics, cannot be adequately characterized by a single model relationship between shear stress and shear rate. Consequently, scientists have developed numerous constitutive models tailored for non-Newtonian fluids. Sutterby17 introduced the constitutive equations for the non-Newtonian Sutterby fluid, which are applied in various fields such as polymer engineering, electronic cooling systems, and compact heat exchangers. Several studies pertaining to the Sutterby fluid have been documented in the scientific literature. Hayat et al.18 conducted a study on the peristaltic flow of the Sutterby fluid in a curved channel with consideration for radiation effects. Their research revealed that, for larger curvature parameters, the velocity distribution becomes symmetrical about the central line. Nawaz19 explored the behavior of hybrid nanoparticles within a Sutterby liquid and applied the Galerkin finite element method to obtain numerical solutions. Song et al.20 conducted an extensive analysis of bioconvection flow in a Sutterby nanoliquid under melting conditions. Their investigation revealed a significant enhancement in velocity distribution at higher Marangoni numbers. Mughanam and Almaneea21 undertook a numerical investigation of Sutterby nanofluid, and their results supported the use of tri-nanofluid for optimising heat transfer processes. Azam et al.22 reported on the bio-convection effects of Sutterby nanofluid, taking into consideration activation energy and microorganisms. They observed an increase in the microorganism population with a rise in the Peclet number. Azam23 introduced a model for Sutterby nanofluid that incorporates aspects of bioconvection and chemical reactions in an axisymmetric flow framework. The research indicated amplification in the microorganism population associated with higher Peclet numbers. Nadeem et al.24 presented a numerical assessment of Sutterby nanoliquid flow through a pipe, demonstrating an increase in fluid hotness in the presence of greater Eckert numbers. Asfour and Ibrahim25 employed magneto Sutterby nano liquid, incorporating a modified version of Darcy's law, and utilized a combination of dual-step difference transparent and finite approach to obtain solutions. Nadeem et al.26 conducted a theoretical investigation of Sutterby nano liquid, accounting for the influence of thermal slip, and obtained numerical solutions using the bvp4c function. Recent research by Du et al.27, Fan et al.28, and Qu et al.29 has explored diverse uses of liquids in the incidence of various nanoparticles. In recent times, numerous academics have dedicated their efforts to addressing heat transfer issues and surface density considerations in the context of both metallic and non-metallic materials. These investigations have encompassed topics such as hydrate-bearing sediments within a granulated thermodynamic structure30, the characterization of heat as well as pressure-dependent pore microstructures31, strain and distortion examination coupled with temperature fields32, the transportation of colloids within 2D absorptive media33, the study of pressure pulsations in centrifugal pumps34, and the analysis of energy moderation in warm electrons over their interaction with optical properties35. Furthermore, a substantial body of valuable work concerning fluid flow modeling is referenced in36,37,38,39,40. Akbar et al.41 investigated the 3D magnetized flow of viscous fluid with thermal radiation under the influence of viscous dissipations. Li et al.42 discussed the buoyancy effect on 3D MHD hybrid nanofluid with slip effect. Nazir et al.43 reported the thermal characteristics of Carreau fluid with hall forces using FE-method. Similarly, Imran et al.44 reported the Ellis fluid over flexible framework with entropu generation. Liu et al.45 gave numerical results for hybrid nanofluid over vertical channel with sorect influence.

The novel effect of this study is to explore the influences of mixed convection, and activation energy on 3D Sutterby nanofluid across a bi-directional extended surface under the impact of thermophoresis diffusion and convective heat dissipation. The flow equations are simplified in terms of PDEs and improved to non-dimensional ODEs by implementing classical scaling invariants. Numerical results have been obtained via the bvp4c approach. The physical insights of crucial and relevant parameters on flow and energy profiles are analyzed through plotted visuals. Some factors have multiple solutions due to shrinking sheets. So stability analysis has been adapted to analyses stable solutions. Graphical representations demonstrate the reliability and accuracy of the numerical algorithm across a variety of pertinent parameters and conditions. A comparison between existing results and previously published data shows a high degree of compatibility between the two datasets. The present study extensively explored a multitude of practical applications across a diverse spectrum of fields, including but not limited to gas turbine technology, power generation, glass manufacturing, polymer production, wire coating, biochemical engineering, heat exchangers, geothermal production, and food processing.

Model description

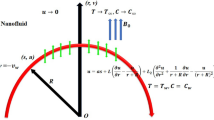

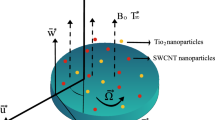

The present flow problem comprises the steady-state incompressible flow of Sutterby nanomaterials with a fixed density across a bi-directional stretchable surface along the xy-direction underneath the inspiration of viscous dissipation and variable thermal conductivity. The model incorporates the mass conservation relation, momentum and energy conservation expressions, and concentration equations. The mathematical framework considers the Arrhenius activation energy effect, mixed convection implications, and the effect of chemical processes occurring during fluid flow. The Buongiorno nanofluid model is designed to incorporate both thermophoresis and Brownian motion. Moreover, it is presumed that the host fluid is laminar and that the tiny materials are in a thermal stability state with the host fluid. The extended sheet is positioned at \(z^{*} = 0\), and the fluid flow is induced by the bi-directional surface movement. The sheet is stretched along \(x\)- and \(y\)-axis with velocity \(U_{w} = \lambda_{1} ax^{*}\) and \(V_{w} = by^{*}\), respectively, where \(a \, and \, b\) are constant with inverse time dimensions. Also it is assumed that \(T_{w}^{*} ({\text{surface temperature}})\) > \(T_{\infty }^{*} ({\text{ambient temperature}})\).Similarly,\(C_{w}^{*} ({\text{concentration}})\) > \(C_{\infty }^{*} ({\text{ambient concentration}})\). Figure 1a is provided to facilitate the clear understanding of this communication.

For Sutterby nanofluid model17 the stress tensor \({\varvec{\tau}}\) is achieved and formulated through the following expression:

With viscosity19

here \(\beta\) represents the material's time constant, \(n\) stands for power law index, and \(\mu_{0}\) denotes the viscosity at zero shear rate. Substituting Eq. (2) into Eq. (1), we obtain:

For Sutterby fluid model the shear rate \(\overline{\gamma }\) is formulated as

In the context of 3D, incompressible, and steady nanofluid flow, the basic flow equations are19:

Here are the basis expressions that describe the Sutterby nanofluid flow problem, comprising nonlinear resulting expressions categorized into mass conservation, momentum, energy, and concentration expressions are stated as17,19:

where \(a^{*}\) shows thermal diffusivity, \(D_{{T^{*} }}\) thermophoretic diffusion coefficient, \(K_{1}\) Boltzmann constant, \(\beta_{{T^{*} }}\) thermal expansion coefficient, \(C_{p}\) specific heat, \(\nu\) viscosity, \(Ea\) Arrhenius energy factor, \(g\) gravitational force and \(D_{B}\) Brownian effect. Consequently, the boundary conditions pertaining to the geometry of the problem are presented underneath42:

In mathematics, it is an extensive exercise to streamline a set of PDEs through the application of similarity transformations. This method entails the introduction of new variables connected to the initial variables by means of a scaling factor. Consequently, the subsequent transformations are frequently employed19:

With the assistance of Eq. (12) and ensuring compliance with the continuity Eq. (6), the resulting highly nonlinear expressions can be formulated as follows:

Moreover, the appropriate boundary conditions are expressed as follows:

Non-dimensional parameters

It is looked over that the nonlinear system stated earlier is predominantly measured and controlled by the following non-dimensional data involved in Eqs. (13)–(17) are simulated and enumerated beneath:

\(\left( {\lambda = \frac{{\beta_{{T^{*} }} g\left( {T_{w}^{*} - T_{\infty }^{*} } \right)}}{{a^{2} x^{*} }}} \right)\) mixed convection parameter, \(\left( {\beta_{1} = \beta^{2} ax^{*} \sqrt {\frac{a}{\nu }} } \right)\) Sutterby fluid parameter, \(\left( {E = \frac{Ea}{{T_{\infty }^{*} K_{1} }}} \right)\) activation energy parameter, \(\left( {\beta_{2} = \beta^{2} ay^{*} \sqrt {\frac{a}{\nu }} } \right)\) Sutterby fluid parameter, \(\left( {Nb = \frac{{\tau^{*} D_{B} \left( {C_{w}^{*} - C_{\infty }^{*} } \right)}}{\nu }} \right)\) Brownian behavior particles \(\left( {Ec = \frac{{\left( {ax^{*} } \right)^{2} }}{{C_{p} \left( {T_{w}^{*} - T_{\infty }^{*} } \right)}}} \right)\) Eckert number, \(\left( {Nt = \frac{{\tau^{*} D_{{T^{*} }} \left( {T_{w}^{*} - T_{\infty }^{*} } \right)}}{{\nu T_{\infty }^{*} }}} \right)\) thermophoresis parameter, \(\left( {\Pr = \frac{\upsilon }{{a^{*} }}} \right)\) Prandtl number, \(\left( {\alpha = \frac{{\beta_{{C^{*} }} \left( {C_{w}^{*} - C_{\infty }^{*} } \right)}}{{\beta_{{T^{*} }} \left( {T_{w}^{*} - T_{\infty }^{*} } \right)}}} \right)\) buoyancy parameter, \(\left( {\gamma = \frac{a}{b}} \right)\) ratio of stretching rates, \(\left( {\delta = \frac{{T_{w}^{*} - T_{\infty }^{*} }}{{T_{\infty }^{*} }}} \right)\) temperature difference parameter, \(\left( {Sc = \frac{\nu }{{D_{B} }}} \right)\) Schmidt number.

Quantities of engineering concern

In the context of the present analysis, the essential physical quantities of interest, which include the surface friction factor in both the directions, as well as wall-related heat and mass flow rates.

The skin force coefficient in the x*-direction is represented as \(Cf_{{x^{*} }}\) and can be defined as follows:

The determination of \(\tau_{{x^{*} z^{*} }}\), which denotes the respective wall stress in the x*-direction for nanofluid, is established through the following relation:

The following dimensionless expression is obtained by inserting Eq. (19) into Eq. (18):

here, \({\text{Re}}_{x} = {{x^{*} U_{w} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{x^{*} U_{w} } \nu }} \right. \kern-0pt} \nu }\) represents the Reynolds number in the x*-direction.

The correlation for the drag force in the y*-direction, denoted as \(Cf_{{y^{*} }}\), is as follows:

the shear stress in the y*-direction, denoted as \(\tau_{{y^{*} z^{*} }}\), is expressed as follows:

By incorporating Eq. (22) into Eq. (21), it uncovers the ensuing dimensionless form in the normal direction:

here \({\text{Re}}_{y} = {{y^{*} V_{w} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{y^{*} V_{w} } \nu }} \right. \kern-0pt} \nu }\) represents the Reynolds number in the y*-direction.

The expression for \(Nu_{{x^{*} }}\), which symbolizes wall heat transfer, can be formulated in the following manner:

The heat transfers at the wall, represented as \(q_{{w^{*} }}\), computed as follows:

By substituting Eqs. (25) to (24), we obtain the following result:

The representation of wall mass transfer, indicated by \(Sh_{{x^{*} }}\), can be described as follows:

The wall mass flux, denoted as \(q_{m}\), is defined as follows:

Substituting Eq. (28) within Eq. (29) yields.

Stability analysis

The resulting nonlinear differential equations are elucidated numerically via the bvp4c scheme along with the shooting technique. Some parameters exhibit duality, so stability scrutiny is implemented for the present study. Dual solutions occur due to suction and injection. For this purpose, it is significant to find a stability analysis of the problem that is both stable and physically feasible. The procedure adopted for stability purposes is the same as discussed by Merkin46 and Weidman et al.47. The time-dependent flow characteristics (1)–(6) are given below

To find the stability of the solutions, the following transformations are introduced to transform the system to unsteady ODEs as explained by Marken46 and Wiedman et al.47.

Equation (20) in Eqs. (16)–(19), we get

Moreover, the appropriate boundary conditions are expressed as follows:

Using the following expression, the stability solutions are inquired for the steady movement \(u_{0} (\eta ) = J_{0} (\eta ) \, , \, u_{1} (\eta ) = H_{0} (\eta ) \, , \, g_{0} (\eta ) = I_{0} (\eta ),{\text{ and }}h_{0} (\eta ) = F_{0} (\eta )\) that fulfills the far-field boundary conditions as reported by Merkin46 and Wiedman et al.47.

Unknown parameters, \(\gamma\) is the smallest eigenvalues.

In view of (40), Eqs. (35)–(39) become

The boundary conditions are

The steady state linear eigenvalues problem of Eq. (41)–(44) is given below

with

Computational strategy and validation

Nevertheless, numerous semi-analytical and numerical techniques are utilizing to explore nonlinearity within the flow problems. Yet, it is significant to note here that the bvp4c method stands out as a more efficient approach. The combination of the shooting technique with this method proves to be a robust approach for ordinary differential equations solutions. The concise bvp4c method effectively handles boundary value problems with precision and efficiency. bvp4c strategy has been widely applied in commercial software such as MATLAB programing platform19. The computational strategy utilized in the shooting method entails transforming the given boundary value problem (BVP) stated in Eqs. (13)–(17) into an initial value problem (IVP). This modified IVP can subsequently be cracked out utilizing the bvp4c technique. Figure 1b presents the flowchart detailing the proposed methodology. Furthermore, we taken a step size of \(\Delta \eta = 0.001\) to calculate the numerical solution with \(\eta_{\max } = 8\), and the convergence criteria is set up to sixth decimal place. The findings demonstrate that selecting \(\eta_{\max } = 8\) satisfies the effect of the boundary layer appropriately. In this approach, variables are assigned based on the order of each equation to convert nonlinear ODEs into first-order linear ODEs. The relevant variables for this purpose are as monitors:

The aforementioned variables are incorporated into Eqs. (13)–(17). The bvp4c method is applied to simplify the graded equations as outlined below:

In line with the following initial conditions:

Furthermore, to enhance the study and facilitate learning of the bvp4c numerical method, a flowchart is depicted via Fig. 1b.

After establishing the mathematical model for incompressible Sutterby nanofluid flow, which takes into consideration the impact of viscous flow features, the next step involves developing a computational algorithm to solve these governing equations. Before initiating any simulations, it is essential to verify the precision of the code. This section's objective is to delineate the authentication of the adopted method and to compare the results acquired with those already recorded in the existing literature. The accuracy and trustworthiness of the existing nonlinear computations are confirmed through a comparison of its solutions with the prior research conducted by Ariel48. Figure 2a,b demonstrates a remarkable alignment between the results obtained in this study and the data documented in earlier literature.

(a, b) A comparative analysis between the current findings and previously published data48.

Dual solutions and analysis

Nanofluids offer a reliable means to enhance the heat transfer rate of conventional fluids. However, simply dispersing nanoparticles within a fluid is not enough to achieve this. Limitations exist within the chemical and thermophysical characteristics of the fluid, and nanofluids are employed to bridge this gap. Furthermore, a specialized thermophysical relationship between viscosity and thermal conductivity is employed in this study to significantly improve the conduction performance of the fluids. The model problem under consideration involves a stretching/shrinking surface, where turbulence reduction is critical for stability. To address this, a magnetic field is introduced into the flow field. The flow pattern is considered to be steady. The solution to the proposed problem is computed using bvp4c techniques, and its validity has been established through a review of existing literature. Notably, this section focuses on the primary concern of the flow field and thermal analysis, with the model parameters playing a pivotal role in achieving this goal.

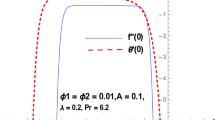

Due to stretching and shrinking sheet, dual solutions occur for some physical parameters. Therefore, the stability analysis is implemented as discussed in “Stability analysis” section. The linearized Eqs. (46)–(50) are numerically solved using the bvp4c approach. The graphical illustration of the multiple solutions is provided in Fig. 3. The smallest positive eigenvalues demonstrate a stable, while the negative eigenvalues report unreliable solutions for the suction parameter, as reported by Merkin46 and Wiedman et al.47. The common point that combines the first and second branches is known as the critical point i.e., \(\beta_{c} = 0.2225\) as shown in Fig. 3. The stability analysis is significantly implemented to analyses the stable branch when multiple branches occur.

Figures 4 and 5 represent the impact of \(a\) and \(Ec\) on the Local Skin Friction (LSF) and Local Nusselt Number (LNN) regarding \(\gamma\) and \(Nt\), respectively. Dual exploration has been explored for \(a\) and. The solid line reports the first branch while the dashed line identifies the second solutions. The critical quantities for \(a = 0.0, 0.8,\) and \(1.4\) are \(\gamma_{c1} = 0.5454\), \(\gamma_{c2} = 0.5035\), and \(\gamma_{c3} = 0.1716\), respectively. It is interesting to note here that the LSF enhances for the growing values of \(a\) in the first solution while declining in the second solution, as publicized in Fig. 4. Furthermore, the heat rate drops in the first as well as second solutions as the quantities of \(Ec\) are increased as depicted in Fig. 5. The corresponding critical values for \(Ec\) = 0.2, 0.5 and 1.0 are \(Ec_{c1} = 0.5454\), \(Ec_{c2} = 0.5035\), and \(Ec_{c3} = 0.1716\), respectively. The relations between \(\gamma\) and stretching/shrinking sheet factor \(\lambda_{1}\) on the LSF and LNN is reported in Figs. 6 and 7, correspondingly. It is investigated that the LSF enhances with the growing magnitudes of \(\gamma\) and \(\lambda_{1}\) while reverse effect is observed for LNN. In Fig. 6 it is significant to note that dual expression occurs in the second branch. In the range \(- 3 \le \lambda_{1} < 2\), decline behavior is observed for the LNN while in the range \(2 \le \lambda_{1} \le 3\) increasing behavior is reported. Additionally, the impact of \(\beta_{1}\) on the LSF and LNN is displayed in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively ragrading stretching/shrinking parameter \(\lambda_{1}\) and Prandtl number \(Pr\). It is interesting to note here that as the \(\beta_{1}\) is increased, the profiles of \(f^{\prime \prime } \left( 0 \right)\) decelerated while the profile \(- \theta^{\prime } \left( 0 \right)\) is increased in the first branch, which gives admirable settlement with the outcomes described by Waini et al.49. This analysis shows a 3.8% increase in heat rate as \(\beta_{1}\) enhanced. This analysis proved that when \(\beta_{1}\) is enhanced, the thermal efficiency of the host fluid enhances. Also, it is reported that as the wedge surface moves at \(\lambda_{1} = 1.0\), the LSF become zero i.e., \(f^{\prime \prime } \left( 0 \right) = 0,\) due to no FDF on the wedge heating sheet convectively.

Figure 10a,b exhibits the flow nature of the velocities \(u_{0}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\;and\;u_{1}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) profiles for the Sutterby fluid parameter \(\beta_{1}\). It is discerned that the both fluid profiles display opposite behavior when the \(\beta_{1}\) is raised. Actually, the elevating data of \(\beta_{1}\) diminishes the internal resistance of the fluid layers and resultantly, fluid velocity distribution \(u_{0}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) grows and \(u_{1}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) profile drops. The contribution convection fluid factor \(\lambda\) via \(u_{0}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\;and\;u_{1}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) is estimated through Fig. 11a,b. Clearly, it is measured that greater exalting estimation of convection parameter \(\lambda = 0.0, \, 0.5, \, 1.0, \, 1.5\) enhances the fluid velocity \(u_{0}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) however an inverse trend in the fluid velocity \(u_{1}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) profile is witnessed. Physically, such scenario is noticed for the increasing positive data of \(\lambda\) correspond to assisting flow which improve velocity field \(u_{0}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\). It is important to pointed out that the fluid convection factor \(\lambda\) classifies as forced convection flow for \(\lambda = 0\) and free convection observed in case of larger estimation of convection parameter i.e. \(\lambda = \infty\). Furthermore, in case of the convection factor \(\lambda\) is greater than zero, it indicates flow assisting flow, whereas when \(\lambda\) is less than zero, it implies flow opposing flow. Aftermath of incrementing data of ratio of stretching rates parameter \(\gamma = 0.2, \, 0.4, \, 0.6,{ 0}.8\) is interpreted through Fig. 12a,b. The behavior velocity \(u_{1}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) is augmented due to increasing values of \(\gamma\) parameter while an opposite tendency in flow field of nanofluid \(u_{0}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) is anticipated in these outlines. In reality, higher estimation of \(\gamma\) attribute in the acceleration of extension rate in the y − direction. Consequently, the flow rate profile \(u_{1}^{\prime } \left( \eta \right)\) augmented in y − direction.

The outcomes of \(Ec \, and \, Nb\) parameters via the thermal field \(g_{0} \left( \eta \right)\) is sketched through Fig. 13a,b. It is apparent that the profile and respective thermal layer are incremented with greater amplification of the parameter. Physically, magnifying enhances the internal kinetic energy fluid nanoparticles. Thus, the fluid temperatureswell up. Figure 13b illuminates the aftermath of the particles diffusion factor on heat gradient. As anticipated, increases. Physically, increment inparameter accelerate the diffusion rate inside the fluid particles, and at this stage, particles acceleration and its impact against the fluid play a significant role regarding the heat transmission mechanism. As expected, raise inincreases the disordered movement of fluid particles. Therefore, the kinetic energy of the entire fluid uplifts and ultimatelyincreases. Figure 14a,b explains variations in subject to. As estimated, temperature profile uplifts through higher estimation of thermophoresis. Physically, thermophoresis force swells when thermophoresis is augmented. In such scenario the exalting behavior of thermophoretic force helps to enhance the disorder movement of liquid particles by hotter region towards colder region. Thus, increase. Impact of on thermal field curves is exposed in Fig. 14b. As witnessed, a reduction behavior in noticed against the expending estimation of the number. According to the physical insight of, the increasing Pr is a reciprocal impact to the thermal diffusivity of the liquid. Therefore, expanding nature of number uplift the diffusivity. Thus, both temperature and thermal boundary layer distribution reduces.

The aftermath of Eckert number and Brownian diffusion on concentration is probed through Fig. 15a,b. It is reported that the concentration of nanoparticle is marked down for the higher rating of parameter highlighted through Fig. 15a. Figure 15b interfaces the impacton fluid distribution. Clearly, it is mentioned that escalating data of aggrandizes the distribution nanoparticles concentration. Physically, expanding nature of uplifts the diffusion process and disordered movement by which nanoparticles move with diverse direction with random particles movements due to the Brownian effect. Subsequently, concentration profile and corresponding thickness of the fluid layer falls. The characteristics of and on are observed through Fig. 16a,b. It is evaluated that concentration is directly influenced by the higher estimation of the thermophoresis force parameter. Physically, uplifting data of increases the count of nanoparticle due to which molecules move from hotter to cooler surfaces. As a result, increases outlined via Fig. 16a, whereas differing behaviors via greater estimations of values is witnessed in Fig. 16b. Figure 17a–c explains the variations in regarding to swelling values of activation energy, Schmidt number, and chemical reaction factors. As estimated, the fluid concentration profile is enlarged due to the expanding supplement of energy parameter shown through Fig. 17a. The impressions of are sketched in Fig. 17b. Here, it is looked over that the greater approximation of σ replicates in the reduction of distribution. The reason for such scenario is that expending values of implies larger destruction due to the chemical process which dissolves liquefies liquid species efficiently. Thus, reduces. Figure 17c explains Schmidt number effect against . Actually, Schmidt number and mass diffusivity are inversely related. Hence, higherowns a reduction in concentration outline. Physically, mass diffusion declines when Schmidt number uplifts. Consequently, decreases. Streamlines are plotted for two different values of \(\beta_{1} = 2\) and \(\beta_{1} = 4\) as shown in Fig. 18. For different values of \(M\) streamlines are declined. The isothermal flow for the given model is explored in Fig. 19 using different values of radiation factor. It is revealed that as the value of \(R_{d}\) increases from \(Nt\) = \(0.2\) to \(Nt\) = \(1.2\), the isothermal flow enhances.

Closing remarks

The novel aspect of present analysis is that, it scrutinizes the incompressible steady flow of 3D Sutterby nanofluid across a bidirectional extended surface, including the influences of activation energy, mixed convection, viscous dissipation, and chemical reaction. Effects of thermophoresis diffusion and Brownian movement motion is deliberated in the model problem. The modeled resulting nonlinear PDEs are diminished into a dimensionless system of ODEs using resemblance replacements. Subsequently, the obtained set of differential equations is resolved statistically49,50,51,52,53. The findings of this study yield several conclusions as follows:

-

Dual exploration has been explored for \(a\) and . The critical quantities for \(a = 0.0, 0.8,\) and \(1.4\) are \(\gamma_{c1} = 0.5454\), \(\gamma_{c2} = 0.5035\), and \(\gamma_{c3} = 0.1716\), respectively.

-

The corresponding critical values for \(Ec\) = 0.2, 0.5 and 1.0 are \(Ec_{c1} = 0.5454\), \(Ec_{c2} = 0.5035\), and \(Ec_{c3} = 0.1716\), respectively.

-

It is interesting to note here that the LSF enhances for the growing quantities of \(a\) in the first solution while declining in the second solution.

-

The heat rate reductions in the first and second solutions is reported as the quantities of \(Ec\) are increased.

-

As notice the fluid velocity along x-direction increases for greater estimation of Sutterby fluid and mixed convection parameters while opposite trend noticed for y-direction flow stream.

-

The energy profile increased by uplifting the magnitude of Eckert number, Brownian, and thermophoresis parameters but decreases by enhancing the values of Prandtl number.

-

The concentration outline decremented with expanding nature of Brownian parameter, and Eckert number, while increases by increasing thermophoresis diffusion parameter and Arrhenius energy parameter.

This study can be improved by adding the slip effect for hybrid nanofluid with stability analysis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Stickel, J. J. & Powell, R. L. Fluid mechanics and rheology of dense suspensions. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 37, 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fluid.36.050802.122132 (2005).

Eastman, J. A., Choi, S. U. S., Li, S., Yu, W. & Thompson, L. J. Anomalously increased effective thermal conductivities of ethylene glycol-based nanofluids containing copper nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 718–720. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1341218 (2001).

Buongiorno, J. Convective transport in nanofluids. J. Heat Transf. 128, 240–250 (2006).

Prasad, P. D., Kumar, R. K. & Varma, S. V. K. Heat and mass transfer analysis for the MHD flow of nanofluid with radiation absorption. Ain Shams Eng. J. 9, 801–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2016.04.016 (2018).

Tian, X. Y., Li, B. W. & Hu, Z. M. Convective stagnation point flow of a MHD non-Newtonian nanofluid towards a stretching plate. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 127, 768–780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.07.033 (2018).

Hayat, T., Qayyum, S., Imtiaz, M. & Alsaedi, A. Comparative study of silver and copper water nanofluids with mixed convection and nonlinear thermal radiation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 102, 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2016.06.059 (2016).

Ahmed, J., Khan, M. & Ahmad, L. Stagnation point flow of Maxwell nanofluid over a permeable rotating disk with heat source/sink. J. Mol. Liq. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2019.04.130 (2019).

Khan, M. I., Kumar, A., Hayat, T., Waqas, M. & Singh, R. Entropy generation in flow of Carreau nanofluid. J. Mol. Liq. 278, 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.12.109 (2019).

Chu, Y. M. et al. Cattaneo-Christov double diffusions (CCDD) in entropy optimized magnetized second grade nanofluid with variable thermal conductivity and mass diffusivity. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9(6), 13977–13987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.09.101 (2020).

Adnan, Zaidi, S. Z. A., Khan, U., Ahmed, N., Mohyud-Din, S. T., Chu, Y.-M., Khan, I. & Nisar, K. S. Impacts of freezing temperature based thermal conductivity on the heat transfer gradient in nanofluids: Applications for a curved Riga surface. Molecules 25(9), 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25092152 (2020).

Ibrahim, M., Saeed, T., Algehyne, E. A., Khan, M. & Chu, Y.-M. the effects of L-shaped heat source in a quarter-tube enclosure filled with MHD nanofluid on heat transfer and irreversibilities, using LBM: Numerical data, optimization using neural network algorithm (ANN). J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 144, 2435–2448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-021-10594-9 (2021).

Akbar, N. S. & Khan, Z. H. Influence of magnetic field for metachoronical beating of cilia for nanofluid with Newtonian heating. J. Magn. Magn Mater. 381(1), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2014.12.086 (2015).

Khan, Z. H., Khan, W. A. & Pop, I. Triple diffusive free convection along a horizontal plate in porous media saturated by a nanofluid with convective boundary condition. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 66, 603–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.07.074 (2013).

Khan, Z. H., Khan, W. A., Hamid, M. & Hongtao, L. Finite element analysis of hybrid nanofluid flow and heat transfer in a split lid-driven square cavity with Yshaped obstacle. Phys. Fluids 32, 093609. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0021638 (2020).

Sharma, T., Sharma, P. & Kumar, N. Entropy generation in thermal radiative oscillatory MHD Couette flow in the influence of heat source. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1849(1), 12023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1849/1/012023 (2021).

Sharma, T., Sharma, P. & Kumar, N. Analysis of entropy generation due to MHD natural convective flow in an inclined channel in the presence of magnetic field and heat source effects. BioNanoScience 9, 660–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-019-00632-0 (2019).

Sutterby, J. L. Laminar converging flow of dilute polymer solutions in conical sections, II. Trans. Soc. Rheol. 9(2), 227–241 (1965).

Hayat, T., Alsaadi, F., Rafiq, M. & Ahmad, B. On effects of thermal radiation and radial magnetic field for peristalsis of sutterby liquid in a curved channel with wall properties. Chin. J. Phys. 55(5), 2005–2024 (2017).

Nawaz, M. Role of hybrid nanoparticles in thermal performance of Sutterby fluid, the ethylene glycol. Phys. Stat. Mech. Appl. 537, 122447 (2020).

Song, Y. Q. et al. Bioconvection analysis for Sutterby nanofluid over an axially stretched cylinder with melting heat transfer and variable thermal features: A Marangoni and solutal model. Alex. Eng. J. 60(5), 4663–4675 (2021).

Mughanam, T. A. & Almaneea, A. Numerical study on thermal efficiencies in mono, hybrid and tri-nano Sutterby fluids. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 138, 106348 (2022).

Azam, M., Mabood, F. & Khan, M. Bioconvection and activation energy dynamisms on radiative sutterby melting nanomaterial with gyrotactic microorganism. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 30, 101749 (2022).

Azam, M. Bioconvection and nonlinear thermal extrusion in development of chemically reactive Sutterby nano-material due to gyrotactic microorganisms. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 130, 105820 (2022).

Abbas, N., Shatanawi, W., Hasan, F. & Shatanawi, T. A. M. Numerical analysis of Darcy resistant Sutterby nanofluid flow with effect of radiation and chemical reaction over stretching cylinder: Induced magnetic field. AIMS Math. 8(5), 11202–11220 (2023).

Asfour, H. A. H. & Ibrahim, M. G. Numerical simulations and shear stress behavioral for electro-osmotic blood flow of magneto Sutterby nanofluid with modified Darcy’s law. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 37, 101599 (2023).

Abbas, N., Shatanawi, W., Shatanawi, T. A. M. & Hasan, F. Theoretical analysis of induced MHD Sutterby fluid flow with variable thermal conductivity and thermal slip over a stretching cylinder. AIMS Math. 8(5), 10146–10159 (2023).

Du, S. et al. Auger scattering dynamic of photo-excited hot carriers in nano-graphite film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121(18), 181104 (2022).

Fan, X. et al. Reversible switching of interlayer exchange coupling through atomically thin VO2 via electronic state modulation. Matter 2(6), 1582–1593 (2020).

Qu, M. et al. Laboratory study and field application of amphiphilic molybdenum disulfide nanosheets for enhanced oil recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 208, 109695 (2022).

Bai, B., Zhou, R., Yang, G., Zou, W. & Yuan, W. The constitutive behavior and dissociation effect of hydrate-bearing sediment within a granular thermodynamic framework. Ocean Eng. 268, 113408 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. Temperature and pressure-dependent pore microstructures using static and dynamic moduli and their correlation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 55, 4073–4092 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. Elastoplastic analytical solution for the stress and deformation of the surrounding rock in cold region tunnels considering the influence of the temperature field. Int. J. GeoMech. 22(8), 4022118 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Fan, D., Cao, S., Lu, W. & Yang, F. Visualization of biochar colloids transport and retention in two-dimensional porous media. J. Hydrol. 619, 129266 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Analysis of surface pressure pulsation characteristics of centrifugal pump magnetic liquid sealing film. Front. Energy Res. 10, 937299 (2022).

Du, S. et al. Competition pathways of energy relaxation of hot electrons through coupling with optical, surface, and acoustic phonons. J. Phys. Chem. C 127(4), 1929–1936 (2023).

Li, S., Khan, M. I., Alzahrani, F. & Eldin, S. M. Heat and mass transport analysis in radiative time dependent flow in the presence of Ohmic heating and chemical reaction, viscous dissipation: an entropy modeling. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 42, 102722 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Analysis of the Thomson and Troian velocity slip for the flow of ternary nanofluid past a stretching sheet. Sci. Rep. 13, 2340 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Numerical bio-convective assessment for rate type nanofluid influenced by Nield thermal constraints and distinct slip features. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 44, 102821 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Effects of activation energy and chemical reaction on unsteady MHD dissipative Darcy–Forcheimer squeezed flow of Casson fluid over horizontal channel. Sci. Rep. 13, 2666 (2023).

Shahsavar, A., Yari, O. & Askari, I. B. The entropy generation analysis of forward and backward laminar water flow in a plate-pin-fin heatsink considering three different splitters. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.105026 (2020).

Akbar, S. & Sohail, M. Three dimensional MHD viscous flow under the influence of thermal radiation and viscous dissipation. Int. J. Emerg. Multidiscip. Math. 1(3), 106–117 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Influence of buoyancy and viscous dissipation effects on 3D magneto hydrodynamic viscous hybrid nano fluid (MgO−TiO2) under slip conditions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 49, 103281 (2023).

Nazir, U. et al. Applications of variable thermal properties in Carreau material with ion slip and Hall forces towards cone using a non-Fourier approach via FE-method and mesh-free study. Front. Mater. 9, 1054138 (2022).

Imran, N., Javed, M., Sohail, M., Qayyum, M. & Mehmood, K. R. Multi-objective study using entropy generation for Ellis fluid with slip conditions in a flexible channel. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 37(27), 2350316 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Numerical investigation of thermal enhancement using MoS2–Ag/C2H6O2 in Prandtl fluid with Soret and Dufour effects across a vertical sheet. AIP Adv. 13(7), 075112 (2023).

Merkin, J. H. Mixed convection boundary layer flow on a vertical surface in a saturated porous medium. J. Eng. Math. 14, 301–313 (1980).

Weidman, P. D., Kubitschek, D. G. & Davis, A. M. J. The effect of transpiration on self-similar boundary layer flow over moving surfaces. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 44, 730–737 (2006).

Ariel, P. D. The three-dimensional flow past a stretching sheet and the homotopy perturbation method. Comput. Math. Appl. 54, 920–925 (2007).

Khan, Z., Rasheed, H. U. & Tlili, I. Runge–Kutta 4th-order method analysis for viscoelastic Oldroyd 8-constant fluid used as coating material for wire with temperature dependent viscosity. Sci. Rep. 8, 14504. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32068-z (2018).

Islam, S., Rasheed, H. U., Nisar, K. S., Alshehri, N. A. & Zakarya, M. Numerical simulation of heat mass transfer effects on MHD flow of Williamson nanofluid by a stretching surface with thermal conductivity and variable thickness. Coatings 11(6), 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11060684 (2021).

S. Rehman, Zeeshan, H. U. Rasheed, S. Islam.Visualization of multiple slip effects on the hydromagnetic Casson nanofluid past a nonlinear extended permeable surface: a numerical approach, Waves in Random and Complex Media, 2022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2022.2051772

Rasheed, H. U. et al. Implementation of shooting technique for Buongiorno nanofluid model driven by a continuous permeable surface. Heat Transfer. 52, 3119–3134. https://doi.org/10.1002/htj.22819 (2023).

Zeeshan, Ahammad, N. A., Shah, N. A., Chung, J. D., Attaullah & Rasheed, H. U. Analysis of error and stability of nanofluid over horizontal channel with heat/mass transfer and nonlinear thermal conductivity. Mathematics 11, 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11030690 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project (number PNURSP2023R183), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors thank the support from the Deanship of Scientific Research, the Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant No. 5315).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Y., Z.Z. wrote the main manuscript and reviewed it, A.S.A., A.H.G. validated the problem and revised for the grammatical mistakes and Z.Z., R.S. confirmed the code and implemented the stability analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yasmin, H., Zeeshan, Z., Alshehry, A.S. et al. A theoretical stability of mixed convection 3D Sutterby nanofluid flow due to bidirectional stretching surface. Sci Rep 13, 22400 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49798-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49798-4

This article is cited by

-

Heat and mass transfer analysis for thermally radiative Sutterby fluid along a stretching cylinder with Cattaneo–Christov heat flux theory

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (2025)

-

Modeling nanomaterial transport with chemical reaction and thermal radiation effects using intelligent learning techniques

Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry (2025)