Abstract

The body fluid status in acute stroke is a crucial determinant in early stroke recovery but a real-time method to monitor body fluid status is not available. This study aims to evaluate the relationship between salivary conductivity and body fluid status during the period of intravenous fluid hydration. Between June 2020 to August 2022, patients presenting with clinical signs of stroke at the emergency department were enrolled. Salivary conductivities were measured before and 3 h after intravenous hydration. Patients were considered responsive if their salivary conductivities at 3 h decreased by more than 20% compared to their baseline values. Stroke severity was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, and early neurological improvement was defined as a decrease of ≥ 2 points within 72 h of admission. Among 108 recruited patients, there were 35 of stroke mimics, 6 of transient ischemic attack and 67 of acute ischemic stroke. Salivary conductivity was significantly decreased after hydration in all patients (9008 versus 8118 µs/cm, p = 0.030). Among patients with acute ischemic stroke, the responsive group, showed a higher rate of early neurological improvement within 3 days compared to the non-responsive group (37% versus 10%, p = 0.009). In a multivariate logistic regression model, a decrease in salivary conductivity of 20% or more was found to be an independent factor associated with early neurological improvement (odds ratio 5.42, 95% confidence interval 1.31–22.5, p = 0.020). Real-time salivary conductivity might be a potential indicator of hydration status of the patient with acute ischemic stroke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and complex disability worldwide, which can lead to serious financial issues for patients and their families1,2. Appropriate treatment of ischemic stroke is essential for reducing mortality and morbidity3. Restoration of the hemodynamic compromise and maintenance of the collateral flow are critical in the acute stage of ischemic stroke4. The hydration status at the time of stroke has been recognized as an important determinant in early stroke recovery5. Reduced intravascular volume upon ischemic stroke has been associated with in-hospital complications, disability, and mortality6. Dehydration is common at the time of stroke due to underlying diseases and swallowing dysfunction7, and may lead to a reduction of cerebral perfusion and reduce the possibility of early stroke recovery8. Current guidelines recommend intravenous fluid supplementation for all patients with ischemic stroke especially when they are dehydrated9.

However, the definition of dehydration is imprecise, and recommendations for hydration therapy are scarce10. In addition, there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of ‘dehydration’ or “inadequate fluid status” in acute stroke patients11,12. Despite availability of bedside assessment of hydration status, its application in acute stroke treatment remains uncertain. Clinically, several blood and urine biomarkers are used to evaluate dehydration, including serum osmolality, urine-specific gravity and osmolality, and serum blood urine nitrogen to creatine ratio11. Although these tests are widely performed, the minimally invasive procedures can become burdensome, especially when repeated within a short period of time. Although urine specimens are non-invasive to collect, urine voiding may not be readily available, especially in dehydrated patient. Moreover, these biomarkers may not fully represent the real-time fluid status and cerebral perfusion13,14. The diagnosis of dehydration, or more accurately, a volume-contracted state, at the time of stroke is challenging as there are currently no consensus diagnostic criteria.

To address these limitations, we developed a portable device for measuring salivary conductivity, which is highly associated with fluid status15,16. This allows for a non-invasive and real-time evaluation of fluid status, and the intensity of hydration treatment may be adjusted in real-time to improve clinical outcomes after acute stroke. Therefore, the purpose of this pilot study was to evaluate the relationship between fluid status and the early clinical response using real-time salivary conductivity in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

This longitudinal observational study was conducted in compliance with the guiding principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (202001388A3C501). Prior to the study, all subjects provided written informed consent.

Study subjects

From September 2020 to May 2021, we screened 214 patients who presented with stroke symptoms at the emergency department of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Chiayi, Taiwan. Out of these, 106 patients were excluded from the study as 52 patients refused to participate, and 54 patients did not complete saliva sampling before hydration upon arriving the ER. Among the remaining 108 eligible patients, 67 patients were diagnosed with acute ischemic stroke, as evidenced by visible ischemic lesions on the subsequent MRI scans, while the other 35 patients were classified as stroke mimics and 6 patients were classified as transient ischemic attack (TIA) (Fig. 1).

Experimental procedures

We explained the experimental design to all patients at the beginning of the study, which included instructions on the collection of saliva, as well as hematological and biochemical examinations. The hydration protocol involved administering a consistent amount of fluids to the patients upon their arrival in the emergency department, at a continuous infusion rate of 80 cm3 per hour. Hydration was provided to all patients unless contraindications were present, such as heart failure or end-stage renal artery disease. Data collection took place at three distinct time points: at the onset of the study, after 3-h period of hydration with normal saline, and 3 days later. There were no restrictions placed on their physical activity following admission.

Salivary collection and analysis

We collected sublingual saliva from the floor of the mouth using a cotton swab and placed it into a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. The salivary sample was centrifugated at 3500 rpm for 5 min and then diluted fivefold with ultrapure water. Salivary conductivity was analyzed using a developed portable monitor equipped with a disposable printed-circuit board electrode. Real-time data on salivary conductivity were immediately recorded (Fig. 2).

Salivary collection and analysis protocol. Salivary conductivity is measured using a printed-circuit board. (A) Collect saliva smoothly with a cotton swab. (B) Place salivary sample in an Eppendorf tube after collection. (C) Centrifuge the salivary sample at 3500 rpm for 5 min. (D) Dilute the salivary sample fivefold with ultrapure water after centrifugation. (E) Analyze salivary conductivity using a developed portable bio-device equipped with a disposable printed-circuit board electrode. (F) Record real-time data of salivary conductivity immediately.

Clinical evaluation of severity of stroke and clinical outcome

In this study, stroke severity was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), and early neurological improvement (ENI) was defined as a decrease of ≥ 2 points on the NIHSS within 72 h of admission. However, patients experiencing fluctuating neurological deficits due to concurrent infections, medications or poorly managed blood sugar levels were not included. The modified Rankin Scale was evaluated at 3 months post-stroke. During hydration therapy, patients were categorized as responsive if their salivary conductivities at 3 h showed a decrease of over 20% from the baseline values.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to examine the normalization of continuous variables. Independent-sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables between the two groups, as appropriate, whereas chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables. Univariate binary logistic regression analysis was performed to compare the frequency of potential factors associated with clinical outcomes. To control for confounding factors, a Forward conditional multivariate binary logistic regression analysis was conducted on variables that showed significance on univariate analysis. The criterion for significance to reject the null hypothesis was a 95% confidence interval. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25 for MAC (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) as used for statistical analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocols of these studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (202001388A3C501). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Results

In this study, 108 patients with clinically suspected stroke in the emergency department were recruited, including 35 of stroke mimics, 6 of TIA and 67 of acute ischemic stroke. We analyzed demographic data from two groups: patients with stroke mimics and those with acute ischemic stroke and TIA (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 69.2 ± 12.6 years. Patients with acute ischemic stroke or TIA were older (71.1 vs. 66.0; p = 0.044) compared to those with stroke mimics. There was no significant difference between the two groups in salivary conductivity at arrival and underlying diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, and chronic kidney disease. Laboratory data of serum glucose and estimated glomerular filtration rate were not significantly different between two groups. The salivary conductivities measured before and 3 h after hydration therapy were higher in patients with acute ischemic stroke and TIA than in those of stroke mimics, but the difference did not reach a statistical significance (9171 vs. 8666 µs/cm, p = 0.535; 8404 vs. 7512 µs/cm, p = 0.330). Compared to the baseline status, salivary conductivity decreased significantly after hydration (9008 vs. 8118 µs/cm, p = 0.030) (Fig. 3). The decreasing trends were observed in both subgroups of stroke mimics (8666 vs. 7512 µs/cm, p = 0.130) and acute ischemic stroke/TIA (9171 versus 8404 µs/cm, p = 0.102) (Fig. 3).

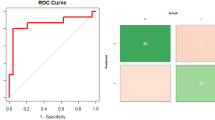

Table 2 shows a total of 67 patients with acute ischemic stroke, of whom 27 were classified as responsive to hydration therapy. Patients with serum osmolarity ≥ 300 mOsm/kgH2O had a higher salivary conductivity before hydration therapy than those with serum osmolarity < 300 mOsm/kgH2O (10,454 vs. 8426 µs/cm, p = 0.037). Compared to the non-responsive group, the responsive group had a higher salivary conductivity at arrival (10,738 vs. 8263 µs/cm; p = 0.007) and a higher rate of ENI within 3 days (37% vs. 10%, p = 0.009). The univariate logistic regression model showed that a decrease in salivary conductivity of ≥ 20%, a more severe NIHSS score and lower blood urea nitrogen were associated with ENI (Table 3). In the multivariate logistic regression model, a decrease in salivary conductivity of ≥ 20% and more severe NIHSS score were found to be an independent factor associated with ENI [odds ratio(OR) 5.42, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.31–22.5, p = 0.020; OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04–1.39, p = 0.016] (Table 3).

Discussion

Our pilot study revealed that salivary conductivity was correlated with fluid status in both ischemic stroke and stroke mimics, suggesting real-time changes of fluid status after intravenous hydration. The response of salivary conductivity was also related to ENI in patients of mild to moderate ischemic stroke. These preliminary results may shed light on real-time monitoring during fluid supplementation in acute ischemic stroke, and further studies are warrant to examine these findings.

Dehydration has been reported as an independent predictor of poor functional outcomes and high admission cost in acute ischemic stroke17,18,19. In a systematic research review by Bahouth et al., hydration status at the time of stroke was recognized as an important determinant in early stroke recovery. In this study, patients with higher osmolarity also had higher salivary conductivity upon arrival, and patients in the hydration-responsive group had higher initial salivary conductivity. These findings may suggest that salivary conductivity may reflect real-time fluid status and accurately detect dehydrated status. However, further studies with large sample sizes are needed to confirm these findings and determine their clinical usefulness.

Intravascular volume depletion is a common occurrence in acute stroke and may exacerbate cerebral blood flow7. Isotonic saline without dextrose is the preferred agent for intravascular fluid repletion and maintenance fluid therapy20. According Lin et al.21, dehydration is an independent predictor of early deterioration after acute ischemic stroke and rehydration can improve outcomes. Another study revealed that urine-specific gravity-based hydration might be a useful method for improving functional outcomes in non-hydrated patients with acute ischemic stroke at admission22. In a Phase III Trial, that the observed benefits of hydration therapy were prominent in patients with mild stroke, as supported by the findings from unpublished randomized controlled trial conducted by Lin et al.23. In our study, patients with acute ischemic stroke who responded to hydration therapy also had a higher chance of ENI, highlighting the importance of adequate hydration for patients with inadequate fluid status. However, patients without a decrease in salivary conductivity may also have inadequate hydration rather than non-dehydration initially.

In patients with acute ischemic stroke, we observed that salivary conductivity measured 3 h after fluid infusion was higher in non-responsive patients compared to the salivary conductivity recorded upon their arrival at the hospital. This could be due to the small amount of intravenous fluid supplementation, which may not be sufficient to correct dehydration caused by inadequate fluid intake related to stroke-related dysphagia or excessive loss of body fluids from the surface. Additionally, the delayed response of salivary conductivity to changes in bodily fluids might contribute to this phenomenon. Furthermore, with prolonged observation, a consistent decrease in salivary conductivity becomes evident, indicating that patients who receive consistent hydration exhibit a salivary conductivity response. Further studies are needed to clarify the association between fluid status and changes in salivary conductivity.

Many parameters have been used to evaluate fluid status in patients with various clinical conditions. Serum osmolality has been shown in several studies to accurately identify hydration state and is sensitive to changes in the dehydration state10,24. However, serum osmolality has a long turnover time and is invasive, making it difficult to reflect real-time hydration status25,26. Urine-specific gravity and urine osmolality are also very sensitive to changes in hydration status, but they lag behind body fluid turnover and are only moderately correlated with serum osmolality during acute dehydration27,28,29. Previous studies have shown that salivary conductivity is a rapid, real-time, and easy-to-administer screening tool for evaluating fluid status15,16. In addition, the saliva test method is simple and non-invasive, allowing for repeated measurements to monitor the fluid status during the period of hydration therapy in acute ischemic stroke.

There were several limitations in the present study. Firstly, the sample size was small, limiting the ability to fully explore the correlation between salivary conductivity and clinical significance in stroke patients. Due to the limited sample size, it is not possible in this study to further categorize the collected samples using TOAST stroke classification for additional meaningful classification and subsequent statistical analysis. Second, salivary conductivity may be influenced by age-related degeneration in the salivary glands30,31. Thirdly, there is a lack of reference ranges and identification of possible confounders for salivary conductivity. Fourthly, salivary conductivity indeed varies in response to changes in fluid status and other medical conditions. Various factors, such as age, impaired salivary functions due to conditions like Sjogren’s syndrome or post-radiation therapy status, serum glucose levels, medications, and endocrine disorders, can influence salivary secretion and conductivity. Impact of these confounding factors may potentially affect level of salivary conductivity. Despite these challenges, the study maintained its focus on observing variations in salivary conductivity following hydration and investigating their association with the clinical response. However, further well-designed prospective studies are warranted to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

Real-time salivary conductivity might be a potential indicator of hydration status of the patients with acute ischemic stroke. Dehydration status may be associated with early neurologic improvement in patients with acute ischemic stroke. This portable monitor device can offer a novel and helpful parameter for the clinical evaluation of hydration status.

Data availability

The datasets during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hsieh, F. I. & Chiou, H. Y. Stroke: Morbidity, risk factors, and care in Taiwan. J. Stroke 16, 59–64 (2014).

Mendelson, S. J. & Prabhakaran, S. Diagnosis and management of transient ischemic attack and acute ischemic stroke: A review. JAMA 325, 1088–1098 (2021).

Lauritano, E. C., Sepe, F. N., Mascolo, M. C., Boverio, R. & Ruiz, L. Diagnosis and acute treatment of ischemic stroke. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials https://doi.org/10.2174/1574887117666220617103114 (2022).

Chien, A. & Vinuela, F. Analyzing circle of Willis blood flow in ischemic stroke patients through 3D stroke arterial flow estimation. Interv. Neuroradiol. 23, 427–432 (2017).

Bahouth, M. N., Gottesman, R. F. & Szanton, S. L. Primary “dehydration” and acute stroke: A systematic research review. J. Neurol. 265, 2167–2181 (2018).

Eizenberg, Y., Grossman, E., Tanne, D. & Koton, S. Admission hydration status and ischemic stroke outcome-experience from a national registry of hospitalized stroke patients. J. Clin. Med. 10, 3292–3299 (2021).

Rodriguez, G. J. et al. The hydration influence on the risk of stroke (THIRST) study. Neurocrit. Care 10, 187–194 (2009).

Tsai, Y. H. et al. Effects of dehydration on brain perfusion and infarct core after acute middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats: Evidence from high-field magnetic resonance imaging. Front. Neurol. 9, 786–790 (2018).

Jauch, E. C. et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 44, 870–947 (2013).

Armstrong, L. E. Assessing hydration status: The elusive gold standard. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 26, 575S-584S (2007).

Lacey, J. et al. A multidisciplinary consensus on dehydration: Definitions, diagnostic methods and clinical implications. Ann. Med. 51, 232–251 (2019).

Kavouras, S. A. Assessing hydration status. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 5, 519–524 (2002).

Perrier, E. T. Shifting focus: From hydration for performance to hydration for health. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 70(Suppl 1), 4–12 (2017).

Murkin, J. M. Retrograde cerebral perfusion: Is the brain really being perfused?. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 12, 249–251 (1998).

Lu, Y. P. et al. A portable system to monitor saliva conductivity for dehydration diagnosis and kidney healthcare. Sci. Rep. 9, 14771–14779 (2019).

Chen, C. H. et al. A portable biodevice to monitor salivary conductivity for the rapid assessment of fluid status. J. Pers. Med. 11, 577–587 (2021).

Liu, C. H. et al. Dehydration is an independent predictor of discharge outcome and admission cost in acute ischaemic stroke. Eur. J. Neurol. 21, 1184–1191 (2014).

Bhalla, A. et al. Influence of raised plasma osmolality on clinical outcome after acute stroke. Stroke 31, 2043–2048 (2000).

Kelly, J. et al. Dehydration and venous thromboembolism after acute stroke. QJM 97, 293–296 (2004).

Burns, J. D., Green, D. M., Metivier, K. & DeFusco, C. Intensive care management of acute ischemic stroke. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 30, 713–744 (2012).

Lin, L. C. et al. Urine specific gravity as a predictor of early neurological deterioration in acute ischemic stroke. Med. Hypotheses 77, 11–14 (2011).

Lin, L. C. et al. Do initially non-dehydrated patients with acute ischemic stroke need fluid supplement?. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 91, 10–15 (2021).

Lin, L. C. A phase III trial of BUN/Cr-based hydration therapy to reduce stroke-in-evolution and improve short-term functional outcomes for dehydrated patients with acute ischemic stroke. ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT02099383.

Kanbay, M. et al. Antidiuretic hormone and serum osmolarity physiology and related outcomes: What is old, what is new, and what is unknown?. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 104, 5406–5420 (2019).

Moon, S. Y., Lee, H. S., Park, M. S., Kim, I. S. & Lee, S. M. Evaluation of the Barricor tube in 28 routine chemical tests and its impact on turnaround time in an outpatient clinic. Ann. Lab. Med. 41, 277–284 (2021).

Shirreffs, S. M., Sawka, M. N. & Stone, M. Water and electrolyte needs for football training and match-play. J. Sports Sci. 24, 699–707 (2006).

Dias, F. C., Boilesen, S. N., Tahan, S., Melli, L. C. & Morais, M. B. Prevalence of voluntary dehydration according to urine osmolarity in elementary school students in the metropolitan region of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 74, 903–907 (2019).

Bar-David, Y., Urkin, J. & Kozminsky, E. The effect of voluntary dehydration on cognitive functions of elementary school children. Acta Paediatr. 94, 1667–1673 (2005).

Armstrong, L. E., Kavouras, S. A., Walsh, N. P. & Roberts, W. O. Diagnosing dehydration? Blend evidence with clinical observations. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 19, 434–438 (2016).

Toan, N. K. & Ahn, S. G. Aging-related metabolic dysfunction in the salivary gland: A review of the literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5835–5848 (2021).

Lamster, I. B., Asadourian, L., Del Carmen, T. & Friedman, P. K. The aging mouth: Differentiating normal aging from disease. Periodontology 2016(72), 96–107 (2000).

Funding

Supported by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital research grants (CMRPG6J0441, CORPG6K0163 and CORPG6N0241).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and the main idea of the work. C.-H.C. and Y.-C.H. drafted the main text, figures, and tables. A.-T.L. and J.-T.Y. supervised the work and provided the comments and additional scientific information. Y.-H.T. and L.-C.L. also reviewed and revised the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, CH., Lee, AT., Yang, JT. et al. An observational study on salivary conductivity for fluid status assessment and clinical relevance in acute ischemic stroke during intravenous fluid hydration. Sci Rep 13, 22460 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49957-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49957-7