Abstract

Periodontitis gradually damages the hard and soft tissues surrounding the tooth, leading to tooth loss. In recent years, the use of biomaterials in periodontitis treatment has expanded, including gels, nanoparticles, microparticles, fibers, and membranes. Among these, membranes have more clinical applications. Due to the ability of the piezoelectric material to regenerate damaged tissues, the aim of this study was to create piezoelectric composite membranes. To achieve this, Barium titanate powder (BaTiO3 powder)—a piezoelectric substance—was synthesized using the hydrothermal method and analyzed with X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). Four types of membranes were fabricated using solvent casting method: three composite membranes with chitosan matrix and BaTiO3 fillers (at 3%, 6%, and 9% weight), and one chitosan membrane without BaTiO3. The microstructure of the membrane surfaces, agglomeration of BaTiO3 in membranes, and hydrophilicity, antibacterial, and electrical properties of the membrane were also investigated. The results indicated that membranes containing 3 and 6% BaTiO3 had suitable surface structure for the periodontitis treatment. Agglomeration of BaTiO3 particles was higher in the membrane containing 9% BaTiO3. The large amount of BaTiO3 improved the antibacterial properties of the membranes. Additionally, the membranes containing BaTiO3 had high electrical properties, especially those with 3% and 6% BaTiO3. Therefore, composite membranes containing BaTiO3, especially membranes containing 6% BaTiO3, are more favorable options than those without BaTiO3 for periodontitis treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Periodontitis is the sixth chronic disease that affects more than 743 million people worldwide1. The periodontium consisting of gingiva, periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone that mechanically supports the teeth and plays an important role in transmitting the mechanical forces generated during chewing2. Periodontal disease is a bacterial infection resulting due to a complex interaction between microorganisms found in dental plaque and host immune response. The disease is characterized by inflammation and progressive destruction of periodontium components3. Among all bacteria, anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria play a more important role in forming periodontitis3. Gingivitis is an earliest stage of periodontal disease and can be prevented with thorough plaque removal and maintenance of effective oral hygiene4. The disease if left untreated leads to periodontitis with alveolar bone destruction and tooth loss4,5. There are many researches which showed that there is a special link between periodontitis and some systemic diseases1,6,7.

Today, among synthetic biomaterials, synthetic membranes known as GTR (Guided tissue regeneration) barrier membranes have found wide clinical use for periodontitis treatment8,9,10,11. These membranes are broadly divided into three generations12. The third-generation membranes are more useful than the first- and second-generation membranes for the treatment of periodontitis. These are biodegradable membranes which prevent unwanted cell penetration to the damaged site and contain antibacterial drugs, growth factor and or bioactive fillers12. Due to some limitations related to membranes containing drugs (large dose requirement)13 and growth factors (short half-life, large dose requirement, and high cost)14, it seems that the use of biodegradable membranes containing bioactive fillers are more useful and economical. Natural collagen polymers are one of the most common materials used in the fabrication of GTR membranes. The disadvantages of these polymers are the fast degradation rate and weak mechanical strength15. Aliphatic thermoplastic polymers such as PLA (polylactic acid), PGA (polyglycolic acid), and their copolymers are the most common synthetic degradable polymers. The disadvantages of these polymers are lack of cell adhesion and flexibility5, and the acid accumulation during the degradation of these polymers may significantly reduce the pH of the damaged site and lead to a chronic inflammatory response11.

Chitosan application in bone tissue engineering has increased due to the similarity of chitosan structure with the bone extracellular matrix structure and its promising biological properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, degradation products non-toxicity, and antimicrobial properties5. Unlike synthetic polymeric biomaterials such as PLA, which remains rigid in the aqueous environment, chitosan is flexible in the aqueous environment. The membrane flexibility is useful during the membrane placement in the damaged site, and it makes the membrane to be implanted optimally5,15. Also, chitosan has a good affinity with human periodontal ligament cells and facilitates osteoblasts adhesion and proliferation, which are responsible for new bone formation5.

In previous studies, bioactive fillers such as natural hydroxyapatite fillers extracted from chicken femur5, synthetic hydroxyapatite16,17, bioactive glasses4,15, multilayer carbon nanotubes18 and beta-tricalcium phosphate19 have been used in the composition of GTR composite membranes. The main purpose of using these fillers in membrane composition has been to improve the ability of apatite formation on the membrane surfaces. But apart from improving the ability of apatite formation, improving the cell activities on the membrane surface (adhesion and proliferation of periodontium’s cells) also increases the efficiency of the membrane in periodontitis treatment5. Hence, in the chemical composition of GTR membrane, we need some kind of fillers that simultaneously increase the ability of apatite formation and the adhesion and proliferation of periodontium’s cells on the membrane surface. Generated electrical pulses of piezoelectric scaffolds improve specific cellular activities such as cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation20. Electrical effects including piezoelectricity, pyroelectricity, and dielectricity play an important role in bone regeneration21. BaTiO3 has interesting ferroelectric, piezoelectric, pyroelectric properties with high dielectric constant22, and bioactivity20. It has also shown antibacterial activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria23,24.

Considering the favorable properties mentioned about chitosan and BaTiO3, the aim of our study is to fabricate suitable composite membranes with chitosan matrix and BaTiO3 fillers use for the treatment of periodontitis.

Materials and methods

Materials

In this research, Titanium oxide (TiO2, Loba Chemie, 25nm), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Merck), Barium hydroxide (Ba(OH)2, Merck), 1- Decanethiol (As a surfactant, Aldrich), Chitosan powder (medium molecular weight, 190–310 KDa, 75–85% deacetylated, Aldrich), Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Nanomer Biomaterials Institute), Acetic acid (Aldrich), Mueller–Hinton agar (QUELAB), and Normal saline (Iranian Parenteral and Pharmaceutical Company) were used.

Synthesis of BaTiO3 powder

BaTiO3 powder was synthesized using the hydrothermal method25. First, a solution containing 0.240 g (0.0030 mol) TiO2 in 21 mL distilled water and a solution containing 0.945 g (0.0055 mol) Ba(OH)2 in 21 mL distilled water were prepared. While stirring both solutions in 2 separate beakers, one of the solutions was added drop by drop to the other solution to form a new solution. A solution containing 1.200 g NaOH (0.0300 mol) in 21 mL distilled water was prepared and added drop by drop to the new solution while stirring. Finally 450 µL 1-decanethiol was added to the new solution until the final solution is prepared (It should be noted that the stirring process in all stages was accomplished by ultrasonic bath for 15 min). The final solution was transferred to the autoclave and the autoclave was placed inside the oven under 180 °C for 2 h. After 2 h, the product inside the autoclave was washed five times with distilled water, and dried at room temperature. To achieve the final product, the dried powder was placed in the furnace at 800 °C for 2 h25.

Membrane preparation

Four membranes with chitosan matrix and BaTiO3 fillers (with weight percentages of 0, 3, 6, and 9) were fabricated by solvent casting method. For fabricating a chitosan membrane without BaTiO3, First, 0.5 g chitosan was poured into a beaker containing 25 mL diluted acetic acid (24.5 mL distilled water plus 0.5 mL pure acetic acid), and the mixture was stirred (500 rpm) by a magnetic stirrer at room temperature for 5 h until chitosan powder is completely dissolved. Then, the solution containing chitosan was poured into a petri dish (with a diameter of 10 cm) and placed in an oven at 40 °C for 48 h to remove the solvent from the petri dish. In order to neutralize the membrane inside the petri dish, NaOH solution (7 g NaOH in 100 mL distilled water) was placed inside the petri dish for 15 min. After removing the NaOH solution, the membrane was separated from the Petri dish and washed 5 times with distilled water. Finally, the membrane was placed in an incubator at 37 °C for drying. For fabricating composite membranes containing BaTiO3, 0.015 g (3 wt %), 0.030 g (6 wt %), and 0.045 g (9 wt %) BaTiO3 were poured into three separate beakers containing 24.5 mL distilled water and were ultrasonicated (by an Ultrasonic Homogenizer, FAPAN 1200UT) for 5 min. Next, 0.5 mL of acetic acid was added to each beaker. Then, 0.485 g, 0.470 g, and 0.455 g chitosan powder were added to the beakers containing 0.015 g, 0.030 g, and 0.045 g BaTiO3, respectively, and the materials inside the beakers were stirred (500 rpm) with the magnetic stirrer at room temperature for 5h until chitosan powder is completely dissolved. The contents of 3 beakers were poured into 3 separate Petri dishes and placed in the oven at 40 °C for 48 h to remove the solvent from the Petri dishes. The steps of neutralization, washing, and drying of these membranes were accomplished in the same way as the chitosan membrane without BaTiO35.

After fabricating the membranes, membranes containing 0, 3, 6, and 9 wt. % BaTiO3 were coded as C/0B, C/3B, C/6B and C/9B, respectively. Figure 1a and b show the fabrication method of membranes containing BaTiO3 and the weight percentages of the membranes ‘constituents, respectively.

Membranes in the final stage of their fabrication (when they are separated from the Petri dish) will have two surfaces with different characteristics. A surface of the membrane that is in contact with the air (SCA surface) will be rougher than the other surface of the membrane that is in contact with the petri dish (SCP surface)5.

Phase identification in the synthesized powder and the membranes surfaces

X-ray diffractometer (Philips Netherlands Company with Cukα radiation, wavelength 1.54 A°) was used for phase analysis of the synthesized powder and the SCA surfaces of the membranes26.

Imaging of the synthesized powder and the membranes surfaces

After the gold coating on the powder, a field emission electron microscope (FESEM, TESCAN MIRA-3) was used to capture an image of the powder. Samples with dimensions of 1 × 1 cm2 were prepared from the fabricated membranes and gold coating was applied on the SCA and SCP surfaces of the membranes. Then, the SCA and SCP surfaces were imaged by the field emission electron microscope, and the distribution of barium, titanium and oxygen elements on the SCA surfaces of membranes was surveyed by mapping system15.

Prepared circular samples of membranes with 1cm diameter were placed on an opaque black surface and their surfaces were photographed by a digital camera. Then, the circular samples surfaces were imaged by a digital microscope (with the same magnification for all samples). Figure 2 illustrates imaging method of membranes surfaces by the digital microscope27.

Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy for membranes

Membranes with dimensions of 1 × 5 cm2 were prepared. Then, the wavelength-absorbance curves of the membranes were obtained by a visible-ultraviolet spectrometer (Shimadzu UV-1800, the wavelength range: 200–800 nm)28.

Hydrophilicity assay for membranes

Membranes hydrophilicity was evaluated by the sessile drop method. In order to perform this test, membranes with dimensions of 1 × 1 cm2 were prepared (5 samples from each membrane) and both surfaces of the membranes (SCA and SCP surfaces) were positioned 3 mm away from the tip of a Hamilton syringe filled with 5 µL of PBS drop. Then, PBS drops were placed on the membrane surfaces, and images of the drops were captured using a digital camera. This procedure was repeated five times for each surface of C/0B, C/3B, C/6B and C/9B membranes. Finally, ImageJ software was used to measure the contact angle of the PBS drops on the membrane surfaces29.

Antibacterial assay for membranes (agar diffusion method)

In this test, Escherichia coli bacteria (an anaerobic Gram-negative bacterium) was used23,30. To prepare the bacterial medium, first, 4 to 5 colonies of pure-young standard strain of Escherichia coli bacterium were transferred to normal saline solution and the bacteria concentration in normal saline solution was standardized using a 0.5 McFarland standard. Next, 10 µL of bacterial suspension (containing 1.5 × 108 bacteria) was lawn-cultured on a plate containing Mueller–Hinton agar using a sterile swab, and the plate was placed at room temperature for 10 min to absorb its moisture. Then, C/0B, C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes were punched in a circle shape (diameter 6 mm) and sterilized by a UV device. The membranes finally were placed on the plate surface and the plate was placed upside down for 24 h at 37 °C inside the incubator. After 24 h, the zone of inhibition around the membranes were measured by using vernier calliper in mm and photographed by a digital camera31.

Electrical test for membranes

Samples with dimensions of 1 × 1 cm2 were prepared from C/0B, C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes. The samples were individually placed on the anvil of holder connected to the LCR Meter (KEYSIGHT, E4980AL) (see Fig. 3). Then 4 µL of PBS solution was poured on the membrane surfaces and the holder rod was placed on the PBS drop. After 1 min, the electrical parameters of each membrane, including electrical conductivity (G) and electrical capacity (C) were recorded by the LCR Meter device at different frequencies (f: 102–103 Hz). The dielectric constant (ε∘) and intrinsic conductivity (\(\sigma \)) of the membranes were calculated by following formulas:

In these formulas, ɛ˳, A, and d are the vacuum permeability constant, the effective area of the membrane (area of the membrane that is in contact with the cross section of the holder rod), and the membrane thickness, respectively32.

Results and discussion

The structure and purity of the synthesized powder

Figure 4a shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of the synthesized powder. The nature of the powder diffraction pattern was investigated using High Score Plus software. According to software search, individual peaks at angles of 22.3°, 31.7°, 39°, 45.2°, 45.5°, 51.1°, 56.4°, 66°, 70.7° and 75.3° are related to crystal planes of (100), (101), (111), (002), (200), (201), (211), (202), (212) and (301) of tetragonal BaTiO3, respectively. The appearance of two separate peaks belonging to the crystal planes of (002) and (200) at the position of 2θ ~ 45° indicates the formation of tetragonal BaTiO333,34. Also, according to software search, other peaks appearing in this pattern are related to barium carbonate and titanium dioxide. One of the common impurities in the BaTiO3 nanostructure preparation (by different methods) is the presence of barium carbonate, which is not removed from the final product even after washing and purification35. Figure 4b and c show FESEM images of the synthesized BaTiO3 powder. Using ImageJ software, the average size of BaTiO3 particles in Fig. 4c was estimated to be approximately 120 nm.

Investigating the microstructure of membrane surfaces

Figure 5 shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of the SCA surfaces of C/0B, C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes. By comparing Figs. 4a and 5, it can be observed that there are some peaks related to BaTiO3 powder in the membranes containing BaTiO3 (especially the most intense peak at the angle of 31.7°). In C/6B and C/9B membranes, the peaks related to BaTiO3 are more visible, which is due to the high amount of BaTiO3 in their SCA surfaces. Also, a peak is observed in all membranes at angle of 20° which is related to chitosan36,37. By comparing Figs. 4a and 5, the removal of barium carbonate impurity peaks in the membranes containing BaTiO3 seems certain. The removal of these peaks was predictable because in the early stages of membrane fabrication, a mixture of acetic acid and distilled water (24.5 mL plus 0.5 mL acetic acid) was used to dissolve chitosan, and barium carbonate can be dissolved even in diluted acetic acid38.

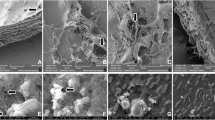

Figure 6 shows FESEM images of the SCA and SCP surfaces in C/0B, C/3B, C/6B and C/9B membranes. In this figure the presence of BaTiO3 particles on the SCA surfaces of membranes containing BaTiO3 is evident, and the amount of BaTiO3 on the SCA surfaces of C/3B, C/6B and C/9B membranes have increased, respectively. Also, there is not much difference between the SCA and SCP surfaces of C/0B membrane and both surfaces are smooth, while the SCA and SCP surfaces of membranes containing BaTiO3 (C/3B, C/6B and C/9B) are rough and smooth, respectively. Hence, it can be concluded that C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes can be more suitable options for periodontitis treatment than C/0B membrane. Because the smooth surfaces of these membranes will be in contact with the gingival tissues, these surfaces prevent the proliferation and penetration of fibroblasts and epithelial cells into the damaged site (these cells inhibit periodontium formation). The rough surfaces of these membranes will be in contact with the damaged site so that these surfaces increase adhesion and proliferation of periodontium's cells that are responsible of periodontium repair5.

In general, the properties of composite membrane depend on the type, amount, and particle size of fillers. It also depends on distribution of fillers in the polymer matrix and the agglomeration of fillers39. Thus, all these factors together determine the properties of the composite membrane.

The distribution of BaTiO3 particles in the composite membranes (C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes) can be evaluated by the distribution of the BaTiO3 constituent elements on the SCA surfaces of the membranes. Figure 7 presents the distribution of barium, titanium, and oxygen elements on the SCA surfaces of composite membranes by elemental mapping. It is possible to evaluate the distribution of BaTiO3 particles in the membranes by the distribution of titanium and barium elements in these membranes, whereas it is not possible to evaluate the distribution of BaTiO3 particles in the membranes by distribution of oxygen elements in the membranes because both chitosan (as the membranes matrix) and BaTiO3 (as the membranes filler) contain oxygen elements. In fact, due to the high oxygen element congestion on the SCA surfaces of the membranes, no difference is observed in the amount of oxygen element congestion on the SCA surfaces of C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes. However, the congestion of titanium and barium elements in the C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes have increased, respectively. The higher congestion of titanium and barium elements on the SCA surface of the C/9B membrane indicates the higher congestion of BaTiO3 particles in C/9B membrane, which can increase the agglomeration rate of BaTiO3 particles in this membrane.

In general, Figs. 6 and 7 demonstrate that the C/9B membrane has more filler congestion than the C/3B and C/6B membranes, which increases the high agglomeration possibility of fillers in the C/9B membrane. Filler agglomeration is one of the basic and controversial problems in the nanocomposites structure, which causes their properties reduction4,40. For example, in nanocomposite membranes, increasing the agglomeration of fillers can cause a decrease in mechanical properties4, dielectric properties22, hydrophilicity, and cell adhesion26.

Figure 8a and c respectively shows the absorbance–wavelength curves of the membranes and the microscopic images of membrane surfaces (by the digital microscope), which were used for investigating the agglomeration of BaTiO3 particles prepared in this work (see Fig. 8b). It has been reported that increasing the filler agglomeration in composite films causes noise formation in the absorbance–wavelength or transmission-wavelength curves of the films41. Figure 8a also shows noise creation in a region of the absorbance–wavelength curve of the C/9B membrane (wavelength between 400 and 200 nm). Increasing the filler agglomeration has a great effect on reducing the transparency of the composite membrane42. In nanocomposite membranes, the increase in the filler agglomeration causes an increase in light scattering, which consequences can the reduction of membrane transparency and the foggy area formation (haze) on the membrane surfaces43. Figure 8c also shows the foggy area formation on the C/9B membrane surface. Thus, according to our results, Fig. 8a and c estimate high agglomeration of BaTiO3 fillers in the C/9B membrane.

Investigating the membrane’s hydrophilicity

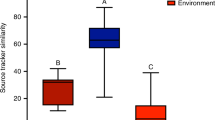

Figure 9a and b show graph of the contact angle and PBS drops morphology on SCA and SCP surfaces, respectively. In each of the C/0B, C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes, the SCA surface is more hydrophilic than the SCP surface. This phenomenon is clearly observed in C/6B and C/3B membranes. But in C/9B and C/0B membranes, a difference of hydrophilicity between the SCA and SCP surfaces is very low. Hence, C/6B and C/3B membranes are more suitable than C/9B and C/0B membranes for periodontitis treatment because more hydrophilic surfaces of these membranes promote the proliferation of periodontium cells in to the damaged site and less hydrophilic surfaces prevents the penetration of fibroblasts in to the damaged site4,15.

Investigating the membrane’s antibacterial properties

Figure 10 shows the zone of inhibition around the membranes by using agar diffusion method. After 24 h of placing the membranes in the bacterial medium, the diameter of the bacterial inhibition zone in C/0B, C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes increased to 6.4 mm, 6.6 mm, 8 mm, and 8.4 mm, respectively. Studies have shown that the antibacterial properties of BaTiO3 particles are directly related to the concentration of these particles23,24. Hence, it seems that the increase of BaTiO3 in the membranes causes an increase in the bacterial inhibition zone. In general, BaTiO3 in small amount (3 wt %) and chitosan polymer have a very small effect in improving the antibacterial properties of the membranes. While BaTiO3 in large amounts (6 and 9 wt %) has a relatively large effect on improving the antibacterial properties of the membranes.

Investigating the membrane’s electrical properties

Figure 11 indicates that the electrical ability of membranes containing BaTiO3, especially C/3B and C/6B membranes, is more suitable than that of C/0B membrane for periodontium repair. When the membranes are placed on the damaged periodontium and then the alternating electric current applied to the damaged region, the dielectric constant and the intrinsic conductivity of the membranes will play important roles in the periodontium repair44. High intrinsic conductivity of the membranes enhances adhesion and proliferation of periodontium's cells that are responsible for periodontium repair45,46, while the high dielectric constant of the membranes promotes the ability of apatite formation on the membranes surfaces that is useful for repairing the bony component of periodontium47,48.

Figure 11a and b show the curves of dielectric constant and intrinsic conductivity of C/0B, C/3B, C/6B, and C/9B membranes in the frequency range of 102–103 Hz, respectively. At any frequency, the dielectric constant and intrinsic conductivity of the membranes containing BaTiO3, especially C/3B and C/6B membranes, are more than those of the membranes without BaTiO3 (C/0B). Also, at any frequency, the dielectric constant and intrinsic conductivity of the C/9B membrane are less than those of the C/3B and C/6B membranes, which is probably due to the high agglomeration of BaTiO3 particles in C/9B membrane22.

Conclusion

In this study, the powder of BaTiO3 nanoparticles is successfully synthesized by hydrothermal method. Using the solvent casting method, it is possible to fabricate suitable chitosan membranes containing 0, 3, 6, and 9 wt % BaTiO3.

In our study, XRD analysis indicates that the chemical composition of the composite membranes containing BaTiO3 does not contain barium carbonate impurity, which usually present in the BaTiO3 powder. The membranes containing 3 and 6% BaTiO3 have a rough surface with high hydrophilicity and a smooth surface with low hydrophilicity, making them superior for use in periodontitis treatment because the rough surface with high hydrophilicity can be in contact with the damaged periodontium, promoting adhesion and proliferation of periodontium’s cells, leading to faster repair of the damaged tissue. The smooth surface with low hydrophilicity can be in contact with the gingival tissue and prevent unwanted cell penetration to the damaged site. The composite membrane containing 9% BaTiO3 has a high particle congestion rate, which increases the agglomeration of BaTiO3 particles in the membrane. The large amount of BaTiO3 improves the antibacterial properties of the membranes. Furthermore, the electrical ability of membranes containing BaTiO3, especially those containing 3% and 6% BaTiO3, is more than that of membranes without BaTiO3 which plays an important role periodontium repair.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that composite membranes containing BaTiO3, especially membranes containing 6% BaTiO3, are more suitable for periodontitis treatment than chitosan membranes without BaTiO3.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Rajeshwari, H. R. et al. Local drug delivery systems in the management of periodontitis: A scientific review. J. Control Release 307, 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.06.038 (2019).

Vaquette, C. et al. Tissue engineered constructs for periodontal regeneration: Current status and future perspectives. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 7, 1800457. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201800457 (2018).

Jain, N. et al. Recent approaches for the treatment of periodontitis. Drug Discov. Today 13, 932–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2008.07.010 (2008).

Dehnavi, S. S., Mehdikhani, M., Rafienia, M. & Bonakdar, S. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of polycaprolactone/PEG/bioactive glass nanopowders nanocomposite membranes for GTR/GBR applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 90, 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2018.04.065 (2018).

Bee, S. L. & Hamid, Z. A. Characterization of chicken bone waste-derived hydroxyapatite and its functionality on chitosan membrane for guided bone regeneration. Compos. B Eng. 163, 562–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.01.036 (2019).

Chen, S., Hao, Y., Cui, W., Chang, J. & Zhou, Y. Biodegradable electrospun PLLA/chitosan membrane as guided tissue regeneration membrane for treating periodontitis. J. Mater. Sci. 48, 6567–6577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-013-7453-z (2013).

Gao, X. et al. Fabrication of antioxidative and antibacterial surface coatings with metformin-loaded self-assembled multilayers for periodontal regeneration in diabetes mellitus patients. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 18668–18683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-021-06533-6 (2021).

Liang, Y., Luan, X. & Liu, X. Recent advances in periodontal regeneration: A biomaterial perspective. Bioact. Mater. 5, 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.02.012 (2020).

Bottino, M. C., Thomas, V. & Janowski, G. M. A novel spatially designed and functionally graded electrospun membrane for periodontal regeneration. Acta Biomater. 7, 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.019 (2011).

Florjanski, W. et al. Modifications of polymeric membranes used in guided tissue and bone regeneration. Polymers 11, 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11050782 (2019).

Gümüşderelioğlu, M., Sunal, E., Tolga Demirtaş, T. & Kiremitçi, A. S. Chitosan-based double-faced barrier membrane coated with functional nanostructures and loaded with BMP-6. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 31, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-019-6331-x (2020).

Sam, G. & Pillai, B. R. Evolution of barrier membranes in periodontal regeneration-“are the third generation membranes really here?”. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 8, ZE14–ZE17. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/9957.5272 (2014).

Han, U., Seo, Y. & Hong, J. Effect of pH on the structure and drug release profiles of layer-by-layer assembled films containing polyelectrolyte, micelles, and graphene oxide. Sci. Rep. 6, 24158. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24158 (2016).

O’brien, F. J. Biomaterials & scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Today 14, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1369-7021(11)70058-X (2011).

Mota, J. et al. Chitosan/bioactive glass nanoparticle composite membranes for periodontal regeneration. Acta Biomater. 8, 4173–4180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2012.06.040 (2012).

Yang, F., Both, S. K., Yang, X., Walboomers, X. F. & Jansen, J. A. Development of an electrospun nano-apatite/PCL composite membrane for GTR/GBR application. Acta Biomater. 5, 3295–3304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2009.05.023 (2009).

Liao, S. et al. The degradation of the three layered nano-carbonated hydroxyapatite/collagen/PLGA composite membrane in vitro. Dent. Mater. 23, 1120–1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2006.06.045 (2007).

Yang, J. et al. Growth of apatite on chitosan-multiwall carbon nanotube composite membranes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 255, 8551–8555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2009.06.013 (2009).

Kuo, S. M. et al. Guided tissue regeneration with use of β-TCP/chitosan composite membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 112, 3127–3134. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.29664 (2009).

Ahmadi, N., Kharaziha, M. & Labbaf, S. (BaCa) TiO3 nanopowder: Synthesis and their electrical and biological characteristics. Mater. Chem. Phys. 226, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.12.081 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Electroactive BaTiO3 nanoparticle-functionalized fibrous scaffolds enhance osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 12, 4007–4018. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S135605 (2017).

Phan, T. T. et al. Enhancement of polarization property of silane-modified BaTiO3 nanoparticles and its effect in increasing dielectric property of epoxy/BaTiO3 nanocomposites. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Dev. 1, 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsamd.2016.04.005 (2016).

Raja, S. et al. Synthesis, characterization and remedial aspect of BaTiO3 nanoparticles against bacteria. Nanomed. Nanobiol. 2, 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1166/nmb.2015.1014 (2015).

Boschetto, F. et al. Bacteriostatic behavior of PLA-BaTiO3 composite fibers synthesized by centrifugal spinning and subjected to aging test. Molecules 26, 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26102918 (2021).

Zhu, X. et al. BaTiO3 nanocrystals: Hydrothermal synthesis and structural characterization. J. Cryst. Growth 283, 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2005.05.080 (2005).

Prokhorov, E. et al. Chitosan-BaTiO3 nanostructured piezopolymer for tissue engineering. Colloids Surf. B 196, 111296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111296 (2020).

De Santis, F. & Pantani, R. Optical properties of polypropylene upon recycling. Sci. World J. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/354093 (2013).

Sirviö, J. A. & Visanko, M. Highly transparent nanocomposites based on poly (vinyl alcohol) and sulfated UV-absorbing wood nanofibers. Biomacromolecules 20, 2413–2420. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.9b00427 (2019).

Yuan, Y., Hays, M. P., Hardwidge, P. R. & Kim, J. Surface characteristics influencing bacterial adhesion to polymeric substrates. RSC Adv. 7, 14254–14261. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA01571B (2017).

Mizerska, U. et al. Bacterial cell killing properties of silver-loaded polysiloxane microspheres. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 7125–7137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-018-2084-z (2018).

Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion susceptibility test protocol. ASM 15, 55–63 (2009).

Rahman, P. M., Mujeeb, V. A., Muraleedharan, K. & Thomas, S. K. Chitosan/nano ZnO composite films: Enhanced mechanical, antimicrobial and dielectric properties. Arab. J. Chem. 11, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.09.008 (2018).

Shah, J. & Kotnala, R. K. Induced magnetism and magnetoelectric coupling in ferroelectric BaTiO3 by Cr-doping synthesized by a facile chemical route. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 8601–8608. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3TA11845B (2013).

Sasirekha, N., Rajesh, B. & Chen, Y. W. Hydrothermal synthesis of barium titanate: Effect of titania precursor and calcination temperature on phase transition. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 47, 1868–1875. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie070986m (2008).

Ansaree, M. J. & Upadhyay, S. Thermal analysis of formation of nano-crystalline BaTiO3 using Ba (NO3)2 and TiO2. Process. Appl. Ceram. 9, 181–185. https://doi.org/10.2298/PAC1504181A (2015).

Llanos, J. H., de Oliveira Vercik, L. C. & Vercik, A. Physical properties of chitosan films obtained after neutralization of polycation by slow drip method. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 6, 276–291. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbnb.2015.64026 (2015).

Takara, E. A., Marchese, J. & Ochoa, N. A. NaOH treatment of chitosan films: Impact on macromolecular structure and film properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 132, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.05.077 (2015).

Krieger, R. Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology: Principles and Agents (Academic press, 2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-426260-7.X5000-9.

Poyraz, B., Eren, Ş & Subaşl, S. Filler type and particle distribution effect on some properties of polymer composites. Celal Bayar Univ. J. Sci. 17, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.18466/cbayarfbe.787883 (2021).

Hammani, S., Barhoum, A. & Bechelany, M. Fabrication of PMMA/ZnO nanocomposite: Effect of high nanoparticles loading on the optical and thermal properties. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 1911–1921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-1654-9 (2018).

Oh, M., Yoon, Y., Jang, E. & Moon, D. Study of dielectric and thermal conductivity characteristics of polyimide composite. Mater. Sci. Appl. 10, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.4236/msa.2019.103016 (2019).

Wildner, W. & Drummer, D. Nanofiller materials for transparent polymer composites: Influences on the properties and on the transparency—A review. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 32, 1547–1565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892705718797157 (2019).

Cho, H. et al. Surface modification of ZrO2 nanoparticles with TEOS to prepare transparent ZrO2@ SiO2-PDMS nanocomposite films with adjustable refractive indices. Nanomaterials 12, 2328. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12142328 (2022).

Chen, C., Bai, X., Ding, Y. & Lee, I. S. Electrical stimulation as a novel tool for regulating cell behavior in tissue engineering. Biomater. Res. 23, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40824-019-0176-8 (2019).

Gopinathan, J. et al. Synergistic effect of electrical conductivity and biomolecules on human meniscal cell attachment, growth, and proliferation in poly-ε-caprolactone nanocomposite scaffolds. Biomed. Mater. 12, 065001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-605X/aa7f7b (2017).

Saberi, A., Jabbari, F., Zarrintaj, P., Saeb, M. R. & Mozafari, M. Electrically conductive materials: Opportunities and challenges in tissue engineering. Biomolecules 9, 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9090448 (2019).

Dang, Z. M. et al. Potential bioelectroactive bone regeneration polymer nanocomposites with high dielectric permittivity. Adv. Eng. Mater. 11, B144–B147. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.200900085 (2009).

Hwang, K. S. et al. Effect of poling conditions on growth of calcium phosphate crystal in ferroelectric BaTiO3 ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 13, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013671526975 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili (UMA) and Isfahan University of Technology (IUT) for using of their laboratory equipment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H. designing the study and writing the manuscript. M.A. supervision, editing the manuscript. Y.A.-K. supervision and editing the manuscript. N.A. supervision. H.S. counseling.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Houshyar, A., Ahmadian, M., Azizian-Kalandaragh, Y. et al. Fabrication and properties evaluation of chitosan/BaTiO3 composite membranes for the periodontitis treatment. Sci Rep 14, 1022 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50929-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50929-0

This article is cited by

-

Comprehensive evaluation and characterization of antimicrobial based packaging film

Journal of Food Science and Technology (2025)

-

Stimuli-responsive materials in oral diseases: a review

Clinical Oral Investigations (2024)