Abstract

The creation of an explicit finite difference scheme with the express purpose of resolving initial boundary value issues with linear and semi-linear variable-order temporal fractional properties is presented in this study. The rationale behind the utilization of the Caputo derivative in this scheme stems from its known importance in fractional calculus, an area of study that has attracted significant interest in the mathematical sciences and physics. Because of its special capacity to accurately represent physical memory and inheritance, the Caputo derivative is a relevant and appropriate option for representing the fractional features present in the issues this study attempts to address. Moreover, a detailed Fourier analysis of the explicit finite difference scheme’s stability is shown, demonstrating its conditional stability. Finally, certain numerical example solutions are reviewed and MATLAB-based graphic presentations are made.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fractional calculus (FC), an extension of classical calculus that involves the integration and differentiation of fractional order, has a rich history dating back to 1695, when the concept of the semi-derivative was first discussed in correspondence between G. W. Leibniz and Marquis de L’Hospital1. Since then, notable mathematicians, including Euler, Liouville, Laplace, Riemann, Grunwald, and Letnikov, have contributed to the development of fractional operators2,3,4,5. The theory of fractional calculus has undergone rapid growth in the 19th century, with applications in various fields, such as fractional geometry, fractional differential equations, and fractional dynamics6,7,8. Today, fractional calculus finds numerous uses in contemporary engineering and research. Methods and tools of fractional calculus are employed in a wide range of fields, including rheology, viscoelasticity, acoustics, optics, chemical and statistical physics, robotics, control theory, electrical and mechanical engineering, and bioengineereing9,11,12,12. The authors of13 considered a 4D memrister system and analyzed its bifurcation, chaos and implement its circuit along with dynamical investigations. The authors of14 discussed in their book with the goal of filling the knowledge gap and giving readers a thorough and organized explanation of the key concepts and uses of fractional calculus. A bibliographic review of fractional-order control laws for robotic manipulators, robot vehicles, man-robot systems, and biologically inspired robots was presented by the authors15. The authors of16 utilized a data-driven approach, the study computes inflation expectations, the monetary policy transparency index, and associated volatility spillover effects. The analysis focuses on the optimization processes of monetary policy transparency that impact inflation and inflation expectations volatility. The most recent advancements and patterns in the use of FC in biology and biomedicine are reviewed by the writers in a paper they published. Nature frequently demonstrates that it operates according to rather basic principles, which cause complex occurrences to arise as a result. Of these, the paper discusses the characteristics of respiratory lung tissue, whose inherent solutions non-integer parametric models and non-integer differ-integral solutions-occur in the middle of FC17.

The application of fractional calculus spans various fields and has gained significant attention in recent years. In physics, fractional calculus has been used to describe anomalous diffusion processes, fractional quantum mechanics, and viscoelasticity in materials18,19. In mathematical biology, fractional calculus has been employed to model the dynamics of populations, the spread of infectious diseases, and the behavior of biological networks20,21. In finance and economics, fractional calculus has been utilized to analyze stock market volatility, option pricing, and fractional order economic models22,23. Furthermore, fractional calculus has found applications in image processing, signal processing, control systems, and many other areas. Its ability to capture memory and long-range dependence provides a powerful tool for modeling complex phenomena in diverse disciplines. In the context of fractional calculus, Caputo derivatives are commonly used24.

Various numerical methods have been proposed by several authors to solve the fractional diffusion equation. Chen et al.25, Birajdar and Dhaigude26, Zhang and Liu27, Liu et al.28, and Lin and Xu29 developed explicit finite difference schemes for solving the fractional diffusion equation, while Birajdar30 obtained stability for a highly nonlinear time fractional diffusion equation. Furthermore, Dhaigue and Birajdar31 applied the discrete Adomian decomposition method to solve various types of fractional partial differential equations. Recently, Kumar et al.32 obtained analytical solutions for fractional differential equations. Despite these advances, fractional calculus is still relatively unknown and has only recently gained widespread applications33.

Luo et al.34 proposed a method for dealing with a specific type of nonlinear fractional difference system that has variable order and fixed initial values. In another study, Luo et al.35 investigated a stochastic fractional differential equation (SFDE) with time delays, specifically stochastic Hilfer-type SHFDEs with non-Lipschitz coefficients. Using the Laplace transform and mathematical inequalities, the authors derived an implicit solution for the SHFDEs and presented an averaging principle36. Additionally, Luo et al.37 proposed the finite-time stability of stochastic fractional-order delay differential equations. Zou et al.38 also derived an averaging principle for the system using mathematical inequalities and novel assumptions. Furthermore, Huang et al.39 studied another type of SFDEs called conformable fractional stochastic differential equations (CFSDEs) that are driven by fractional Brownian motion with infinite delay. The authors used mathematical methods and a fixed-point theorem to investigate the existence of solutions and the controllability of the system.

The aim of this study is to address two significant challenges in the field of fractional differential equations. Firstly, we tackle the lack of stability analysis in many existing methods for solving such equations. To overcome this limitation, we have developed a scheme specifically tailored for variable-order time fractional initial boundary value problems. Additionally, we have conducted a comprehensive stability analysis of the explicit finite difference scheme. Secondly, our scheme is applicable to both linear and semi-linear equations. However, this paper focuses on presenting numerical results related to the application of our scheme to linear equations, an area that has received less attention compared to similar schemes applied to semi-linear equations. Linear time fractional equations offer several advantages, including easier solvability using standard numerical methods, a simpler mathematical structure, and the ability to model a broader range of physical and biological processes. In contrast, semi-linear time fractional equations are typically limited to more specific applications and present challenges in terms of well-posedness. By addressing these difficulties, our study contributes to the advancement of understanding and application of fractional differential equations. It is important to remember that among the definitions of the fractional derivative, the Caputo definition is the one that is most frequently applied. In terms of mathematics, the Caputo definition is more rigorous than the Riemann-Liouville definition for more details the readers can be found in40.

An explicit finite difference strategy for fractional-order equations may have the following possible benefits over alternative approaches to a thorough stability analysis:

Explicit stability criteria designed especially for finite difference schemes used to fractional-order equations are provided by the technique. This provides a precise guideline for assessing stability, making the evaluation process easier than with more generic stability evaluations that do not take into account the special qualities of fractional-order equations. It permits an in-depth numerical stability analysis of the considered finite difference scheme. The approach enables a tailored study with an emphasis on the finite difference scheme’s stability behavior in the setting of fractional-order equations. With this focused approach, the analysis is customized to meet the unique needs and difficulties presented by fractional-order dynamics, which could lead to more insightful and accurate findings. The method can verify if the finite difference scheme is stable by comparing it to theoretical stability bounds or established stability criteria through a thorough stability analysis. For the numerical solution derived from the scheme to be accurate and reliable, this validation phase is essential. It makes it easier to find stable areas in the finite difference scheme’s parameter space, which helps choose the right parameters to guarantee stable numerical solutions. This makes it possible to optimize and tune parameters effectively, which enhances the accuracy and performance of computations. The approach sheds light on possible drawbacks and restrictions in the use of the finite difference strategy for fractional-order equations, as well as its stability bounds. For the numerical solution approach to remain robust and to prevent numerical instabilities, it is imperative to comprehend these stability constraints. The approach makes it possible to optimize scheme parameters to improve stability while preserving computational efficiency, based on the findings of the stability study. To obtain stable and precise numerical solutions, this optimization procedure may include modifying time step sizes, spatial discretization techniques, or other numerical factors. These benefits mean that carrying out a thorough stability analysis of an explicit finite difference scheme for fractional-order equations offers important information and direction for numerical simulations, guaranteeing the accuracy, stability, and dependability of the numerical solution technique in real-world scenarios.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the development of an explicit finite difference scheme, which employs Caputo definition for the time fractional derivative, and the central difference approximation for the space derivative. Additionally, the stability of the scheme is discussed in this section. In Section 3, some examples texted for the validation of the considered scheme. Lastly, we concludes our work in Section 4.

Methodology

In this section, we discuss the explicit finite difference scheme for solving linear or semi-linear variable-order time fractional differential equations. In the end of this section, we discuss the stability of the proposed scheme.

Explicit finite difference scheme

Consider the variable-order time fractional semi-linear differential equation

where

or

The function \(f(\psi )\) is nonlinear. Without \(f(\psi )\) function, the Eq. (1) becomes linear.

Discretization

Let \([0,L_x]\) be the domain of interest, first, we discretize this domain. To do this, let us define \(x_i=ih\), where \(0\le {i}\le {M}\), \(Mh=L_x\), \(t_j=jk\), \(0\le {j} \le {N}\), \(Nk=T\), where h is the space step length and k is time step size. Suppose that \(\psi _i^j\) be the numerical approximation of \(\psi (x_i,t_j)\) and \(f_i^j({\psi _i^j})=f(x_i,t_j,\psi _i^j)\). Further, suppose that the non-linear function \(f_i^j({\psi _i^j})\) satisfies the Lipschitz condition. \(|f_i^j(\psi _i^j)-f_i^j(\bar{\psi }_i^j)|\le {L_p}|\psi _i^j-\bar{\psi }_i^j|, \ L_p\) is a non-negative Lipschitz constant.

Development of the scheme

Considering Eq. (1) in which \(\gamma (x,t)\) represents the fractional order. The fractional derivative of order \(\gamma {(x,t)}\) is defined by Coimbra in terms of Caputo and is defined as

Using forward difference formula for temporal derivative

Equivalently, the above expression can also be written as

Upon Integrating the above equation, we obtain

Using \(\Gamma {(1+\gamma )}=\gamma \Gamma {(\gamma )}\) and expanding the summation for \(l=0\), we reach at

Replace j by \(j+1\)

or

where

Discretization of non-linear function \(f(\psi )\) is given as

Using Eqs. (3) and (4), Eq. (1) takes the form

or

where

Re-arranging the terms, Eq. (1) can be written as

The comparison of the proposed method with previous techniques is given in the Table 1 below.

The following section evaluates the stability of the discrete equation scheme (5, 6, 7).

Stability analysis

The most common technique for stability analysis of the explicit finite difference scheme is the Von Neumann stability analysis, which involves linearizing the problem around a steady state and studying the eigenvalues of the resulting linear system43. It is also possible to use other stability analysis techniques such as Fourier analysis44, Lax-Richtmyer45, and Von Neumann Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) conditions46.

To evaluate the stability of the scheme, we consider \(\rho _i^j=\psi _i^j-\varphi _i^j\), where \(\varphi _i^j\) is the accurate solution at \((x_i,t_j)\) and apply the Fourier method. The discrete function \(\rho ^j(x^*_i)\) is formulated as:

In Fourier series, the function (8) can be expanded

where

Properties of the coefficient \(r_i^j\) and \(d_l^{i,j}\)

-

1.

\(r_i^j>0,\quad 0<b_l^{i,j}<d_{l-1}^{i,j}<1,\)

where \(d_l^{i,{j+1}}=b_l^{i,{j+1}}-b_l^{i,{j+1}},\quad \forall i=1,2,\ldots ,M, l=1,2,\ldots ,N.\)

-

2.

\(0<d_l^{i,j}<1,\quad \sum _{j=0}^{k-1}d_{l+1}^{i,{j+1}}=1-b_l^{i,{j+1}}.\)

It is easy to prove property (2).

Stability of the scheme

The stability of the scheme is analyzed in this section. By inserting \(\rho _i^j=u_i^j-U_i^j\) into Eqs. (5, 6)

Evaluating sum for \(l=j\), we get

Simplification yields us

Since

Substituting (11) in Eq. (10), we get

Further simplified to obtain

where

Let solution at grid points be of the form

Simplifying and re-arranging the terms

Using identity \(e^{ix}=cosx+isinx\), and re-arranging the terms

or

The following lemma provides a framework for evaluating the stability of the scheme.

Lemma

Suppose that \(\xi ^j\) be the solution of (14) and \(\forall (i,j), r_i^j\le \dfrac{1}{2\sin ^2\Big (\dfrac{\lambda h}{2}\Big )}\) then \(|\xi ^j|\le C^*|\xi ^0|,\)holds for \(j=1,2,.....,N-1.\)

Proof

Using mathematical induction.

Let \(j=0\), (14) becomes

or

where we have used the result \(d_l^{i,{j+1}}=b_{l-1}^{i,{j+1}}-b_{l}^{i,{j+1}}\).

Taking modulus on both sides

where

For \(j>0\), the Eq. (14) can be written as

Let us now assume that the given result holds for j and prove it for \(j+1\), i.e., it holds \(|\xi ^j| \le C|\xi ^0|\) and we are to show that \(|\xi ^{j+1}|\le C^*|\xi ^{0}|\). Taking modulus on both sides of (15), i.e.,

We know that, \(|\xi ^j|\le C^*|\xi ^0|\) for all \(k>1\).

Since \(\sum _{l=1}^{j-1}d_{l+1}^{i,{j+1}}=1-b_l^{i,{j+1}}<1\), because \(0<b_l^{i,{j+1}}<1.\)

where

The proof follows by induction. \(\square\)

Theorem

Explicit finite difference schemes (56) to (7) is stable under these circumstances, \(r_i^j\le \dfrac{1}{2\sin ^2\big ({\lambda h}/{2}\big )},\quad \forall (i,j)\) \(i=1,2,\ldots ,M\); \(j=0,1,\ldots ,N\).

Proof

To prove that the explicit finite difference schemes given in Eqs. (5, 6) to (7) are stable under the condition \(r_i^j \le \frac{1}{2\sin ^2\left( \frac{\lambda h}{2}\right) }\) for all (i, j), where \(i=1,2,\dots ,M\) and \(j=0,1,\dots ,N\), we can proceed as follows:

Using Eq. (10) and the given lemma, we have:

To establish stability, we need to show that \(|\rho ^j|_2\) remains bounded for all \(j=1,2,\dots ,N\), given the stability condition on the coefficients \(r_i^j\).

First, let’s define \(E^j = |\rho ^j|_2\) for convenience. Our goal is to show that \(E^j\) is bounded for all j.

Using Eq. (7) and the definition of \(|\cdot |2\) norm, we can rewrite \(E^j\) as:

Now, we can analyze the behavior of \(E^j\) in terms of \(E^{j-1}\). By substituting the expression for \(E^j\) and \(E^{j-1}\) into equation (56), we have:

Since \(|\cdot |_2\) norm is a valid norm, we have the triangle inequality:

Therefore, we can bound \(E^j\) as follows:

Thus, we have shown that \(E^j\) is bounded for all \(j=1,2,\dots ,N\).

Therefore, the explicit finite difference schemes (56) to (7) are stable under the given condition. This proves the stability of the scheme. \(\square\)

Numerical experiments

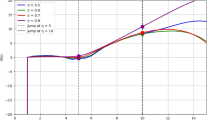

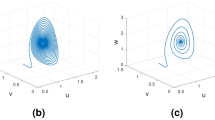

In this section, we present a numerical solution for variable-order time fractional linear initial boundary value problems using an explicit finite difference scheme. We investigate the influence of the fractional order \(\gamma\) by solving problems for different values of \(\gamma\) ranging from 0 to 1. To perform the numerical calculation, we discretize the spatial domain into \(N=10\) equal intervals, each with a step size of h. The final solution is obtained at a specified final time T and stored in a matrix for each \(\gamma\) value. Finally, to visualize the results, we plot the solution against the spatial variable x, with each line representing the solution for a different fractional order value.

All the tests are performed on a Windows 10 Pro operating system using Matlab version R2016b on a computer equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-7200U CPU running at 2.5 GHz and with 8GB of RAM.

Example I

Subject to the conditions:

Solution:

To obtain the discrete form of Eq. (16), the time fractional approximation (3) must be used for the time derivative and the central difference approximation for the space derivative.

Re-arranging the terms,

with

where \(r_i^{j+1}=\dfrac{k^{\gamma _i^{j+1}}\Gamma (2-\gamma _i^{j+1})}{h^2}.\)

The numerical solution for different values of \(\gamma\) at the final time T is depicted in 3D Fig. 1 and also for 2D Fig. 2.

Example II

Subject to the conditions:

Solution:

Using time fractional approximation (3) the (17) can be written as

Re-arranging the terms

with

where \(r_i^{j+1}=\dfrac{k^{\gamma _i^{j+1}}\Gamma (2-\gamma _i^{j+1})}{h^2}\). The numerical solution for different values of \(\gamma\) at the final time T is shown in 3D Fig. 3 and 2D Fig. 4.

Example III

Subject to the conditions:

Solution:

After simplification, (18) becomes

Applying the time fractional approximation (3) to the (18)

Re-arranging the terms,

with

where

In this research paper, we explore three examples of initial boundary value problems involving fractional partial differential equations. In Example I, we consider a problem governed by a time-fractional partial differential equation with a variable-order fractional derivative. The equation exhibits a linear and semi-linear variable-order time fractional characteristic. The Caputo derivative is employed to model physical memory and inheritance, and the problem is solved subject to specified initial and boundary conditions. Example II presents a different equation, also with a variable-order fractional derivative, but involving a different spatial derivative term. The equation includes a term that accounts for the singular behavior near the origin (at x=0) and requires additional boundary conditions at the right boundary (at x=1). Finally, in Example III, we explore a problem described by a time-fractional partial differential equation with a variable-order fractional derivative and a spatial derivative term. This example includes a non-homogeneous initial condition and satisfies zero-flux boundary conditions. By considering these three examples, we demonstrate the versatility and applicability of the explicit finite difference scheme in solving initial boundary value problems with various fractional characteristics, showcasing the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Conclusion and future work

This paper presents a novel explicit finite difference scheme specifically designed for solving initial boundary value problems with linear and semi-linear variable-order time fractional characteristics. The choice of employing the Caputo derivative in this scheme is motivated by its well-established significance in fractional calculus, enabling effective modeling of physical memory and inheritance. The thorough stability analysis using the Fourier method confirms the conditional stability of the proposed scheme. Numerical examples demonstrate the efficacy of the method, with graphical representations using MATLAB showcasing solution curves for different fractional orders. Moving forward, future research directions could include extending the scheme to more complex nonlinear problems, investigating adaptive mesh refinement techniques, exploring the application of the method to other scientific and engineering domains, and considering parallel computing techniques to enhance computational efficiency. This work contributes to the advancement of fractional partial differential equations solving methods and provides a foundation for further exploration and refinement of this approach.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications (Elsevier, 1998).

Gorenflo, R. & Mainardi, F. Fractional Calculus. Fractals and Fractional Calculus in Continuum Mechanics (Springer, 1997).

Nonnenmacher, T. F. & Metzler, R. On the Riemann-Liouville fractional calculus and some recent applications. Fractals 3(03), 557–566 (1995).

Agrawal, O. P. Formulation of Euler-Lagrange equations for fractional variational problems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 272(1), 368–379 (2002).

Haidong, Q., ur Rahman, M., Arfan, M., Salimi, M., Salahshour, S., & Ahmadian, A. Fractal-fractional dynamical system of typhoid disease including protection from infection. Eng. Comput. 1–10 (2021).

Baleanu, D., Diethelm, K., Scalas, E. & Trujillo, J. J. Fractional Calculus: Models and Numerical Methods Vol. 3 (World Scientific, 2012).

Zhang, L., ur Rahman, M., Haidong, Q. & Arfan, M. Fractal-fractional Anthroponotic Cutaneous Leishmania model study in sense of Caputo derivative. Alex. Eng. J. 61(6), 4423–4433 (2022).

Klafter, J., Lim, S. C., & Metzler, R. Fractional Dynamics: Recent Advances (2012).

Majumdar, S. et al. A study of the rheological properties of visco-elastic materials using fractional calculus. Colloids Surf., A 516, 181–189 (2017).

Sun, H. G., Zhang, Y., Baleanu, D., Chen, W. & Chen, Y. Q. A new collection of real world applications of fractional calculus in science and engineering. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 64, 213–231 (2018).

Rahman, M., Althobaiti, A., Riaz, M. B. & Al-Duais, F. S. A theoretical and numerical study on fractional order biological models with Caputo Fabrizio derivative. Fractal Fract. 6(8), 446 (2022).

Mahmood, T., Rahman, M., Arfan, M., Kayani, S.-I. & Sun, M. Mathematical study of Algae as a bio-fertilizer using fractal-fractional dynamic model. Math. Comput. Simul. 203, 207–222 (2023).

Jiang, X., Li, J., Li, B., Yin, W., Sun, L., & Chen, X. Bifurcation, chaos, and circuit realisation of a new four-dimensional memristor system. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 0 (2022).

Kochubei, Anatoly, L., Yuri, T., Vasily, E. & Petráš, I. (eds.) Handbook of Fractional Calculus with Applications. vol. 1. (de Gruyter, 2019).

Chávez-Vázquez, S., Gómez-Aguilar, J. F., Lavín-Delgado, J. E., Escobar-Jiménez, R. F. & Olivares-Peregrino, V. H. Applications of fractional operators in robotics: A review. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 104(4), 63 (2022).

He, Q., Rahman, M. & Xie, C. Information overflow between monetary policy transparency and inflation expectations using multivariate stochastic volatility models. Appl. Math. Sci. Eng. 31(1), 2253968 (2023).

Ionescu, C., Lopes, A., Copot, D., Tenreiro Machado, J. A. & Bates, J. H. T. The role of fractional calculus in modeling biological phenomena: A review. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 51, 141–159 (2017).

Chen, Z., Qiu, P., Yang, X.-J., Feng, Y. & Liu, J. A new fractional derivative model for the anomalous diffusion problem. Therm. Sci. 23(Suppl. 3), 1005–1011 (2019).

Laskin, N. Fractional quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. E 62(3), 3135 (2000).

Jafari, H., Ganji, R. M., Nkomo, N. S. & Lv, Y. P. A numerical study of fractional order population dynamics model. Results Phys. 27, 104456 (2021).

Srivastava, H. M., Saad, K. M., Gómez-Aguilar, J. F. & Almadiy, A. A. Some new mathematical models of the fractional-order system of human immune against IAV infection. Math. Biosci. Eng. 17(5), 4942–4969 (2020).

Li, B., Zhang, T. & Zhang, C. Investigation of financial bubble mathematical model under fractal-fractional Caputo derivative. FRACTALS (fractals) 31(05), 1–13 (2023).

Zhang, X., Ding, Z., Hang, J. & He, Q. How do stock price indices absorb the COVID-19 pandemic shocks?. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 60, 101672 (2022).

Almeida, R. A Caputo fractional derivative of a function with respect to another function. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 44, 460–481 (2017).

Chen, C., Liu, F. & Burrage, K. Finite difference methods and a Fourier analysis for the fractional reaction-subdiffusion equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 198(2), 754–769 (2008).

Birajdar, G. A., & Dhaigude, D. B. An implicit numerical method for semilinear fractional diffusion equation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mathematical Sciences. Chennai, India, 674–678. (2014).

Zhang, H.-M. & Liu, F. Numerical simulation of the Riesz fractional diffusion equation with a nonlinear source term. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 26(1–2), 1–14 (2008).

Liu, F., Shen, S., Anh, V. & Turner, I. Analysis of a discrete non-Markovian random walk approximation for the time fractional diffusion equation. Anziam J. 46, C488–C504 (2004).

Lin, Y. & Chuanju, X. Finite difference/spectral approximations for the time-fractional diffusion equation. J. Comput. Phys. 225(2), 1533–1552 (2007).

Birajdar, G. A. Stability of nonlinear fractional diffusion equation. Lib. Math 36, 1–12 (2016).

Dhaigude, D. B., Birajdar, G. A. & Nikam, V. R. Adomain decomposition method for fractional Benjamin-Bona-Mahony-Burger’s equations. Int. J. Appl. Math. Mech 8(12), 42–51 (2012).

Kumar, P. & Agrawal, O. P. An approximate method for numerical solution of fractional differential equations. Signal Process. 86(10), 2602–2610 (2006).

Zhang, Y., Sun, H. G., Stowell, H. H., Zayernouri, M. & Hansen, S. E. A review of applications of fractional calculus in earth system dynamics. Chaos Solitons Fract. 102, 29–46 (2017).

Luo, D., Abdeljawad, T. & Luo, Z. Ulam-Hyers stability results for a novel nonlinear Nabla Caputo fractional variable-order difference system. Turk. J. Math. 45(1), 456–470 (2021).

Luo, D., Zhu, Q. & Luo, Z. An averaging principle for stochastic fractional differential equations with time-delays. Appl. Math. Lett. 105, 106290 (2020).

Luo, D., Zhu, Q. & Luo, Z. A novel result on averaging principle of stochastic Hilfer-type fractional system involving non-Lipschitz coefficients. Appl. Math. Lett. 122, 107549 (2021).

Luo, D., Tian, M. & Zhu, Q. Some results on finite-time stability of stochastic fractional-order delay differential equations. Chaos Solitons Fract. 158, 111996 (2022).

Zou, J., Luo, D. & Li, M. The existence and averaging principle for stochastic fractional differential equations with impulses. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 46(6), 6857–6874 (2023).

Huang, J. & Luo, D. Existence and controllability for conformable fractional stochastic differential equations with infinite delay via measures of noncompactness. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci.33(1) (2023).

Abd-Elhameed, W. M. & Youssri, Y. H. Generalized Lucas polynomial sequence approach for fractional differential equations. Nonlinear Dyn. 89, 1341–1355 (2017).

Alia, A., Abbasb, M. & Akramc, T. New group iterative schemes for solving the two-dimensional anomalous fractional sub-diffusion equation. J. Math. Comp. Sci 22, 119–127 (2021).

Oderinu, R. A., Owolabi, J. A. & Taiwo, M. Approximate solutions of linear time-fractional differential equations. (2023).

Balsara, D. S. Von Neumann stability analysis of smoothed particle hydrodynamics—suggestions for optimal algorithms. J. Comput. Phys. 121(2), 357–372 (1995).

Fornasini, E. & Marchesini, G. Stability analysis of 2-D systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 27(12), 1210–1217 (1980).

Palencia, C. & Sanz-Serna, J. M. An extension of the Lax-Richtmyer theory. Numer. Math. 44, 279–283 (1984).

González García, S. Contribuciones al método de las diferencias finitas para la resolución de las ecuaciones de Maxwell en el dominio del tiempo. (1994).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thanks the referee for relevant remarks and comments which improved the final version of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.: writing original draft, methodology; S.B.: resources, formal analysis, corresponding author, conceptualization; RS: resources, review and editing, BT: writing review and editing; and MR: formal analysis, review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanwal, A., Boulaaras, S., Shafqat, R. et al. Explicit scheme for solving variable-order time-fractional initial boundary value problems. Sci Rep 14, 5396 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55943-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55943-4