Abstract

Microplastics, particles under 5 mm, pervade aquatic environments, notably in Tarragona’s coastal region (NE Iberian Peninsula), hosting a major plastic production complex. To investigate weathering and yellowness impact on plastic pellets toxicity, sea-urchin embryo tests were conducted with pellets from three locations—near the source and at increasing distances. Strikingly, distant samples showed toxicity to invertebrate early stages, contrasting with innocuous results near the production site. Follow-up experiments highlighted the significance of weathering and yellowing in elevated pellet toxicity, with more weathered and colored pellets exhibiting toxicity. This research underscores the overlooked realm of plastic leachate impact on marine organisms while proposes that prolonged exposure of plastic pellets in the environment may lead to toxicity. Despite shedding light on potential chemical sorption as a toxicity source, further investigations are imperative to comprehend weathering, yellowing, and chemical accumulation in plastic particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microplastics (MP), plastic particles or fragments smaller than 5 mm, have become widespread along the aquatic environments worldwide, posing a serious environmental problem due to their persistence, durability and toxic potential1. MPs are commonly classified as primary, intentionally produced within this size range, and secondary, derived from the degradation of larger plastics fragments, such as meso- and macro-plastics2.

Plastic pellets, typically found within primary MPs, are raw materials used to manufacture large scale plastic products, thus making them a common item found on sandy shores all over the world3,4. These items can be released into the environment during manufacturing and transport or as a result of accidental spills during marine and terrestrial shipping5. For instance, industrial pellets are listed as the main source of MPs to the marine environment in Spain6. Therefore, numerous studies have been conducted to understand their distribution in marine environments, the potential mechanical impacts on marine organisms and consequently their harmful effects on marine organisms (e.g. Ref7). Plastic materials may contain “plastic additives” used to improve their performance, such as phthalates (PAEs), organophosphate esters (OPEs) or bisphenols (BPs)8. Besides that, there is an increased interest on the accumulation of hydrophobic chemicals by the pellets. Given their large surface:volume ratio, microplastics have a high ability to absorb hydrophobic organic contaminants (HOCs) from water, effectively concentrating these substances. Also they show the potential to transfer these substances to organisms upon ingestion, although this topic is subject of debate9,10,11.

In fact, plastic pellets act as passive samplers accumulating on their surface organic pollutants present in the surrounding environment12. This aspect is particularly relevant in aquatic environment, where the amounts of environmental organic contaminants adsorbed on the plastic surface can be several orders of magnitude higher than that in the surrounding waters13. Since the first report that highlighted the presence of toxics in pellets14, several other studies have shown the incorporation of toxic compounds in plastic pellets, such as PCBs4,7,15,16,17, dioxin-like chemicals11, OCPs4,17, PAHs17 and DDTs16. Notably, the concentration of these chemicals varies between the different studies and the researched areas. The key factor driving this variability appears to be the time spent in water environment16, where pellets go through weathering and aging effects, mainly via photooxidation2. Due to weathering effect, plastic particles commonly undergo coloring of their surface, in a phenomenon known as “yellowing process”18. This color transformation potentially offers insights into the residence time in the marine environment, distinguishing aged pellets (yellowish, orange and brownish) from their pristine counterparts (white or translucent)19. It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that more white and translucent pellets will be present near the sources of plastic pellets; on the contrary, moving away from the sources, yellowish and brownish pellets will dominate20.

The level of aging, along with the degree of erosion of plastic and the chemical properties of the pollutant, influence the sorption of pollutants; a number of studies, indeed, have noted a greater accumulation of POPs or DLCs in plastic pellets that presents greater aging and coloring7,11,16,17. If the aged and colored pellets present higher concentrations of organic contaminants, then these could be transferred more effectively to the aquatic biota20. It is possible to objectively quantify the degree of yellowing and weathering of plastic particles using the Yellowness Index (YI), which is a percentage value based on the yellowing of the sample and increases according to plastic degradation17.

However, the relationship between the aging process, pollutants accumulation on plastic pellets and their toxicity to aquatic biota, is still poorly understood17; just as it is a complex challenge to trace the life history of each pellet that stranded on the beach21.

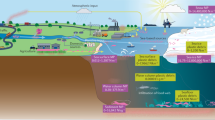

The Tarragona region (Catalunya, NE Spain) is home to one of the largest and most important petrochemical complexes in the Mediterranean. This complex, known as the Chemical Complex of Tarragona (Complejo Petroquímico de Tarragona), encompasses various facilities and plants dedicated to the production, handling and logistics of chemicals and plastics (Fig. 1). The complex is strategically located near the Port of Tarragona for easy transportation of goods. Since 2018, Good Karma Projects association (goodkarmaprojects.org) has dedicated efforts to investigate and document the issue of plastic pellet pollution in Tarragona. Initial reports from witnesses highlighted occurrences of significant pellet influxes on La Pineda Beach and surrounding beaches, particularly coinciding with stormy weather or heavy rainfall in the preceding days. Initially, the prevailing belief was that these incidents were primarily linked to losses in maritime transport or originated from distant sources. However, inspections carried out in 2020 and 2021 by volunteers from our organization, in collaboration with the Corps of Rural Agents of Catalonia, within the region’s hydrographic network, have confirmed the existence of substantial pellet concentrations in these areas. Notably, these concentrations have been identified more than a dozen kilometers inland from the beach, often situated next to the facilities responsible for the production, storage, and distribution of pellets. It is widely acknowledged that companies worldwide, engaged in the handling of plastic pellets, experience unintended chronic and persistent losses22, and in Tarragona this is no exception.

Taking this into account, the main goal of this study is to investigate whether there are variations between plastic pellets found near their source and those collected from beaches at increasing distances from the production source, displaying signs of weathering. Our objective is to test the hypothesis that greater distances from the source lead to increased weathering and a more pronounced yellowing of the pellet samples. Additionally, we conducted toxicity assessments on leachates from these environmental samples, including sub-samples categorized by their color, using the highly sensitive sea-urchin embryo test (SET).

Material and methods

Sampling

Plastic pellets were collected during the spring of 2022, at three locations with increasing distance from a local source of plastic pellets waste (Fig. 1). The samples were collected as part of the Good Karma citizen science program, aiming to identify new accumulation areas in the territory. The samples were taken as evidence of the presence of pellets in these accumulation areas from a square between 50 and 100 cm wide. The sample from the Sant Ramón stream (TR, henceforth) was taken from the side of the channel where pellets accumulate among the vegetation (41° 10′ 00.5″ N 1° 11′ 08.8″ E). In the case of La Pineda Beach (PI, henceforth), samples were collected from the large southern accumulation area of the beach (41° 03′ 58.2″ N 1° 10′ 48.0″ E), about 60 m from the shoreline. Finally, in the case of Cavalleria Beach (CA, henceforth) on the island of Menorca, samples were collected in a central area of the beach, about 20 m from the shoreline, near the dunes (40° 03′ 32.9″ N 4° 04′ 32.8″ E).

Pellets characterization

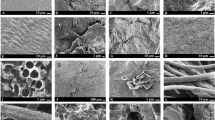

In the laboratory, plastic pellets were rinsed with distilled water to remove any attached debris. The three collected stocks were characterized according to the presence of surface cracking and their yellowness. Additional samples were sent to University of Vigo central services (CACTI) for the identification of the polymer by Fourier-Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) by using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700) equipped with a attenuated total reflectance (ATR) diamond crystal.

For each stock, a representative subsample of 35 individual plastic pellets was examined by unaided visual inspection. The examination focused on the identification of two prominent indicators of photo-oxidative stress, as delineated in the classification system proposed by Hunter et al23. Briefly, plastic pellets were assigned weathering scores as follows: a score of ‘1’ denoted the absence of both yellowing and cracking, ‘2’ indicated the presence of either yellowing or cracking, and ‘3’ signified the coexistence of yellowing and cracking.

To calculate the yellowness index, we developed a Python script for image processing using the SkImage (https://scikit-image.org/)24, Colour (https://www.colour-science.org/)25 and Scikit-learn (https://scikit-learn.org) libraries26. The complete script is available at https://github.com/flaranjeiro/Yellowing_Index_ImageAnalysis and can be applied to any jpg image file. In summary, when you upload an image to the script, all its pixels are analyzed for color. Therefore, it is important to upload pellet images with background removed by photo editors. The software then employs statistical clustering of the color values of each pixel to identify the ten most likely colors in the image, represented in the CIE XYZ color space format. Based on this data, the Yellowness Index is computed by the Colour library, following the formula outlined in the ASTM E131 method.

Additionally, and to better understand the influence of these weathering features on the leachate toxicity, subsamples were generated for both PI and CA stations based on the degree of yellowing. These subsamples included those with no yellowing (designated as PIW and CAW), some degree of yellowing (PII and CAI), and significant yellowing (PIY and CAY). The previously described classifications were also applied on these pellet subsamples. Images of the plastic pellets samples used in this work, and analyzed by the script for Yellowness Index, can be found in supplementary material (Fig. S1).

Toxicity tests

All pellet samples, as previously referred, were grounded with a CryoMill (Retsch) with the aid of liquid nitrogen and then sieved through a 250 µm metallic mesh to obtain a homogenous particle size. The leachate preparation followed standard methods specifically developed for plastic materials27. In summary, 650 mg of each sample was transferred to 65 ml glass bottles containing artificial seawater without any headspace (10 g/L). These bottles were then placed on an overhead rotator (GFL 3040) and gently rotated at 1 rpm for 24 h at a temperature of 20 °C in complete darkness. The resulting leachates were filtered through glass fiber filters (Whatman) previously cleansed with 150 ml of distilled water. Likewise, 200 ml of artificial seawater were filtered and used as control for the bioassays. To ensure optimal testing conditions, various chemical and physical parameters such as temperature, pH, salinity, and dissolved oxygen were monitored. Leachates were tested undiluted and diluted in artificial seawater to 1/3, 1/10 and 1/30.

Marine toxicity of leachates was tested using the SET bioassay according to Beiras et al28. Gametes were obtained by dissection of sexually mature sea urchins Paracentrotus lividus, collected in the outer part of the Ría de Vigo, and kept in stock at the ECIMAT (University of Vigo). Gametes viability (egg roundness and sperm motility) was assessed under the microscope and after that oocytes were transferred to a 50 ml measuring cylinder. A small volume of undiluted sperm, collected with a glass Pasteur pipette, was added to the cylinder, followed by gentle stirring with a plunger. The number of fertilized eggs, characterized by the fertilization membrane, were counted in 20 µl aliquots. Eggs with a density of 40 per ml were moved to airtight glass vials with Teflon-lined caps containing 4 ml of the treatment dilutions. In the bioassay were tested: fertilized eggs that were fixed after delivery, artificial seawater controls and dilutions of the leachates. After 48 h incubation at 20 °C in dark, samples were fixed with three drops of 30% formalin.

Statistical analysis

The maximum length of the first 35 individuals per vials was measured using Leica image analysis software; after that, the size increase was calculated subtracting the mean egg size. Acceptability criteria in controls was fertilization > 95% and pluteus size increase > 253 µm29. Control corrected size increase was fit to a probit function of the leachate dilution, and the median effective concentration (EC50) was calculated as the dilution reducing size increase by 50%.

To determine the normality of the data was used the Shapiro–Wilk test, while ANOVA and Levene’s test were conducted to test differences (p < 0.05) among treatment group means and variances, respectively. In the event of significant differences in homoscedasticity (p < 0.05), Dunnett’s post hoc test was used to compare every treatment with the control treatment (filtered artificial seawater); otherwise, Dunnett’s T3 post hoc was used. Through these tests it is possible to calculate the NOEC (No Observed Effect Concentration) and the LOEC (Low Observed Effect Concentration). Finally, toxic units (TU) were calculated as TU = 1/EC2030. IBM SPSS statistics software V25 was used to conduct statistical analyses.

Results

FTIR results of the randomly selected pellets from the sampled stations have shown a balanced composition of either polyethylene or polypropylene. Detailed analysis can be seen in supplementary material (Fig. S2). It is then fair to assume that both polymers were generally present in all samples and therefore polymer composition wouldn’t influence the obtained results.

The categorization of visual signs of weathering reveals a consistent trend of increased weathering as one moves from inland sources to the farthest point (CA). The majority of pellets are classified as either 2 (46%) or 3 (46%) at CA, in contrast to TR, where no pellets fall into the category of 3, with the majority being classified as 1 (86%) (see Fig. 2A). PI, on the other hand, predominantly consists of pellets classified as 2 (49%). Notably, when considering subsamples selected based on visual inspection, the expected trend of increased weathering from PIW and CAW to PIY and CAY is evident. However, it is important to highlight that weathering classification is consistently higher in CA subsamples compared to their corresponding PI subsamples (eg. CAY > PIY).

As for the Yellowing classification, a similar pattern emerges (see Fig. 2B). The yellowing index generally increases from TR to CA, with less pronounced differences between PI and CA. %YI is slighlty higher in CAY compared to PIY. Interestingly, even within PI subsamples, there is a slightly higher %YI in those with no yellowing and some degree of yellowing when compared to CA. This discrepancy can be attributed to the subjective nature of visually determining color, which can vary within intermediate ranges. For a comprehensive breakdown of results and colors identified through image analysis, please refer to the Supplementary Excel file.

The outcomes of the SET, conducted using the leachates, are summarized in Table 1 (you can find dose–response curves in Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). Notably, the leachate derived from the TR sample exhibited no statistically significant toxic effects across all tested concentrations. However, significant effects were observed when using undiluted leachate from the PI sample, and in the case of the CA sample, toxicity was evident in undiluted and the three times diluted leachate.

It is worth highlighting that despite the absence of toxicity in the PI leachate as a whole, subsamples taken from PI exhibited varying toxic effects. Specifically, there were no significant effects observed in the leachates from PIW. However, both PII and PIY leachates displayed significant effects on larval growth. This time, PII and PIY were found to be slightly toxic. All CA subsamples exhibited slight toxicity, with the most heavily yellowed subsample demonstrating the highest level of toxicity (TU for CAY was 1.9, compared to 1.4 and 1.5 for CAI and CAW, respectively), mirroring the trends observed in PI. More weathered pellets from Pineda beach (PIY) result now to be more toxic than less weathered pellets subsample from Cavalleria (CAW & CAI).

In the regression analysis, we converted the weathering classification from Fig. 2 into percentages, with a maximum classification of 2 corresponding to 100%. The toxicity values used in the analysis were determined by calculating the average impact on larval growth (in percentage of control) observed in the undiluted leachates. Regression analysis (Fig. 3) reveals that the observed toxicity in the leachates cannot be explained by the weathering variables examined when considering all stations or when focusing solely on CA subsamples. In contrast, when looking at the PI subsamples, weathering (p-value < 0.1) and, to a greater extent, the Yellowing Index (p-value < 0.01) appear to have an influence on toxicity. However, it’s crucial to be careful when interpreting these findings due to the limited number of observations utilized in the regression analysis.

Discussion

Plastic pellets have become a ubiquitous element of the ecosystem, been detected in numerous coastal locations worldwide7,17,20,31,32, freshwater ecosystems33,34 as well as in biota, including fish35,36,37 turtles38,39,40 and birds41,42,43. This is also the case for our study area, the Tarragona coast (Western Mediterranean), where microplastics and pellets contamination was previously reported in coastal areas44 and molluscs45.

This is a concerning issue, as plastic pellets have the potential to inflict mechanical harm on marine life by leading to complications such as intestinal blockages, reduced food consumption, and internal injuries7,46. But also, plastic pellets can both transport and absorb chemical compounds from their surroundings4,47, a process potentially influenced by the level of weathering they undergo. Some studies have reported a positive correlation between the extent of chemical contamination on the surfaces of these pellets and the degree of weathering they experience in aquatic environments11,16,17.

Understanding the issue of plastic pellet pollution in the Tarragona region, our research aims to provide fresh insights into the harmful effects of plastic pellets on the early life stages of marine invertebrates. Our proposed classifications confirm that plastic pellets exhibit increased weathering and yellowing as they travel farther from the source of pellet leakage. Comparing full samples there is an increase in weathering (Classification 2 + 3) of 500 and 640% from TR to PI and CA, respectively, while the yellowing increased 504% and 537% in the full sample of the same stations. In subsamples, yellowing increases up to 900% in comparison to those found in TR were registered (Fig. 2). This aligns with findings by De Monte et al.19, who noted that pellets left on beaches and in seawater environments for six months displayed a significant shift in color towards yellow and alterations in surface morphology. Although in our case is not possible to predict how much time pellets have been spent in the environment.

The results of SET, with the leachates of the three samples studied, show an increasing negative effect on larval growth from TR to PI and then to CA, the sample taken at the highest distance from the source which revealed to be slightly toxic. It’s important to note that PI beach is situated immediately after the riverine inflow that carries the pellets from the source to the sea, while CA is located in the Baleares Island in the midst of the Mediterranean. The hydrographic characteristics of the petrochemical complex in Tarragona designate it as a flood-prone region. Consequently, during periods of abundant rainfall, water transports particles from the soil towards the sea. Once in the sea, the pellets remain afloat on the surface, forming accumulations in proximity to their sources along the Tarragona coast. When faced with easterly or southerly winds and waves, the pellets are driven onto La Pineda Beach. Conversely, under conditions of northwesterly or westerly winds (predominant in the region), they are propelled towards the Balearic Sea. Nevertheless, and since no plastic factory is based in Balearic Islands, it’s reasonable to assume that the pellet mixture in CA includes contributions from other sources and various contaminants that may affect the overall toxicity. This could potentially account for the relatively weak correlation between the bioassay results of the sampled pellets and their weathering classifications (see Fig. 3). Nevertheless, to gain deeper insights into the influence of weathering on pellet toxicity, we took the collected samples from PI and CA and divided them into three subsamples based on the degree of pellet weathering. In the case of PI subsamples, those with no apparent weathering (PIW) exhibited no toxic effects, like what we observed in TR. However, as the level of weathering increased in the pellets, so did the negative impact on toxicity. Notably, both PII and PIY displayed slight toxicity, a phenomenon that was not observed in the assessment of the full sample. It’s worth noting that the weathering and yellowness classifications in these subsamples exhibit a strong correlation with the toxic effects of undiluted leachates (refer to Fig. 3). Likewise, the EC20 values also appear to be significantly influenced by these characteristics. As mentioned earlier, the PI sample was collected relatively close to the local source of pellet production, ensuring sample homogeneity in terms of origin. However, there exists heterogeneity in the residence time of these pellets in the environment, with those exposed for longer periods demonstrating increased toxicity. This information holds significant importance both in monitoring pellet toxicity and in managing this type of pollution. It becomes evident that even if these plastics can be considered chemically harmless at the time of production can turn toxic after an extended period in the environment. This is the case in all the CA subsamples, as they consistently displayed slight toxicity, in line with the results observed in the original CA sample. This may be attributed to the fact that, despite our attempt to categorize them into three distinct groups, all the pellets in CA had experienced a significant degree of weathering and yellowing. It’s also important to consider that this sample is likely more diverse in terms of the pellets’ sources of origin. However, even though there is no direct correlation between the toxicity of undiluted leachate and the weathering classifications (as shown in Fig. 3), both the EC50 and, notably, the EC20 demonstrate that the most weathered category is more toxic than the others.

The impact of leachates from environmental pellets on biota remains a relatively understudied and unmonitored area. Nevertheless, several studies have indicated more pronounced negative effects on embryo development when comparing beach-collected pellets to industrial polypropylene pellets in brown mussels48 or Polyethylene pellets in P. lividus larvae49. Similarly, research with the fish Pimephales promelas has shown that leachates from beached pellets are more likely to cause mortality and deformities compared to leachates from industrial polypropylene or polyethylene50. This can be justified by the fact that plastics have a high ability to absorb hydrophobic organic contaminants (HOCs) from water, effectively concentrating these substances10,11. Because of constraints related to pellet availability, we were unable to conduct chemical analyses on these samples. However, previous studies have corroborated elevated levels of toxic chemicals in weathered or aged pellets11,17.

These findings, alongside our results, suggest that pellets collected near the source and showing minimal weathering, are more likely to be less toxic when compared to pellets displaying significant signs of weathering and yellowing. The latter may have been exposed to the environment for an extended period, potentially leading to the absorption of chemicals from their surroundings. Nonetheless, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon, it will be essential to conduct additional research focused on environmental pellets and the potential toxicity of their leachates to biota. Similarly, further investigations will be necessary to scrutinize the processes of weathering and yellowing that plastic particles undergo, along with the subsequent associations between these processes and the concentration of chemical compounds.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Qu, X., Lei, S., Hengxiang, L., Mingzhong, L. & Huahong, S. Assessing the relationship between the abundance and properties of microplastics in water and in mussels. Sci. Total Environ. 621, 679–686 (2018).

Andrady, A. L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62, 1596–1605 (2011).

Fanini, L. & Bozzeda, F. Dynamics of plastic resin pellets deposition on a microtidal sandy beach: Informative variables and potential integration into Sandy beach studies. Ecol. Indic. 89, 309–316 (2018).

Pozo, K. et al. Persistent organic pollutants sorbed in plastic resin Pellet — “Nurdles” from coastal areas of central Chile. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 151, 110786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110786 (2020).

Ryan, P. The characteristics and distribution of plastic particles at the sea-surface off the southwestern Cape Province. S. Afr. Mar. Environ. Res. 25, 249–273 (1988).

Martín-Lara, M. A., Godoy, V., Quesada, L., Lozano, E. J. & Calero, M. Environmental status of marine plastic pollution in Spain. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 170, 112677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112677 (2021).

Endo, S. et al. Concentration of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in beached resin pellets: Variability among Individual particles and regional differences. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 50, 1103–1114 (2005).

Fauvelle, V. et al. Organic additive release from plastic to seawater is lower under deep-sea conditions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4426. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24738-w (2021).

Beiras, R., Tato, T. & López-Ibáñez, S. A 2-Tier standard method to test the toxicity of microplastics in marine water using Paracentrotus lividus and Acartia clausi larvae. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 38, 630–637 (2019).

Lohmann, R. Microplastics are not important for the cycling and bioaccumulation of organic pollutants in the oceans—but should microplastics be considered POPs themselves?. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 13, 460–465 (2017).

Chen, Q. Marine microplastics bound dioxin-like chemicals: Model explanation and risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 364, 82–90 (2019).

Town, R. M. & van Leeuwen, H. P. Uptake and release kinetics of organic contaminants associated with micro- and nanoplastic particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 10057–10067 (2020).

Concha-Graña, E., Moscoso-Pérez, C., López-Mahía, P. & Muniategui-Lorenzo, S. Adsorption of pesticides and personal care products on pristine and weathered microplastics in the marine environment. Comparison between bio-based and conventional plastics. Sci. Total Environ. 848, 157703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157703 (2022).

Carpenter, E. J. & Smith, K. L. Plastics on the Sargasso sea surface. Science 175, 1240–1241 (1972).

Mato, Y. et al. Plastic resin pellets as a transport medium for toxic chemicals in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 318–324 (2001).

Ogata, Y. et al. International Pellet watch: Global monitoring of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in coastal waters. 1. Initial phase data on PCBs, DDTs, and HCHs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 58, 1437–1446 (2009).

Abaroa-Pérez, B., Ortiz-Montosa, S., Hernández-Brito, J. & Vega-Moreno, D. Yellowing, weathering and degradation of marine pellets and their influence on the adsorption of chemical pollutants. Polymers 14, 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14071305 (2022).

Martí, E. et al. The colors of the ocean plastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 6594–6601 (2020).

De Monte, C. et al. An in situ experiment to evaluate the aging and degradation phenomena induced by marine environment conditions on commercial plastic granules. Polymers 14, 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14061111 (2022).

Izar, G. et al. Can the colors of beach-stranded plastic pellets in beaches provide additional information for the environmental monitoring? A case study around the Santos Port, Brazil. Int. Aquat. Res. 14, 23–40 (2022).

Ryan, P., Perold, V., Osborne, A. & Moloney, C. Consistent patterns of debris on South African beaches indicate that industrial pellets and other mesoplastic items mostly derive from local sources. Environ. Pollut. 238, 1008–1016 (2018).

Galafassi, S., Nizzetto, L. & Volta, P. Plastic sources: A survey across scientific and grey literature for their inventory and relative contribution to microplastics pollution in natural environments, with an emphasis on surface water. Sci. Total Environ. 693, 133499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.305 (2019).

Hunter, E. et al. Quantification and characterisation of pre-production pellet pollution in the Avon-Heathcote Estuary/Ihutai, Aotearoa-New Zealand. Microplastics 1, 67–84 (2022).

van der Walt, S. et al. Scikit-image: Image processing in python. PeerJ 2, e453. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.453 (2014).

Mansencal, T. et al. Colour 0.4.3. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8284953 (2022).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Almeda, R. et al. A protocol for lixiviation of micronized plastics for aquatic toxicity testing. Chemosphere 333, 138894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138894 (2023).

Beiras, R., Duran, I., Bellas, J. & Sánchez-Marín, P. Biological effects of contaminants: Paracentrotus lividus sea-urchin embryo test (SET) with marine sediment elutriates. Centro Oceanográfico de Vigo (2012).

Saco-Álvarez, L., Durán, I., Lorenzo, J. I. & Beiras, R. Methodological basis for the optimization of a marine sea-urchin embryo test (SET) for the ecological assessment of coastal water quality. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 73, 491–499 (2010).

Bellas, J., Saco-Álvarez, L., Nieto, Ó. & Beiras, R. Ecotoxicological evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using marine invertebrate embryo–larval bioassays. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 57, 493–502 (2008).

Turner, A. & Holmes, L. Occurrence, distribution and characteristics of beached plastic production pellets on the island of Malta (Central Mediterranean). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62, 377–381 (2011).

Giugliano, R. et al. Rapid identification of beached marine plastics pellets using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy: A promising tool for the quantification of coastal pollution. Sensors 22, 6910. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22186910 (2022).

Lechner, A. et al. The Danube so colourful: A Potpourri of plastic litter outnumbers fish larvae in Europe’s second largest river. Environ. Pollut. 188, 177–181 (2014).

Wang, T. et al. Coastal zone use influences the spatial distribution of microplastics in Hangzhou Bay, China. Environ. Pollut. 266, 115137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115137 (2020).

Cabansag, J., Olimberio, R. & Villanobos, Z. Microplastics in some fish species and their environs in eastern Visayas, Philippines. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 167, 112312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112312 (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Seasonal distributions of microplastics and estimation of the microplastic load ingested by wild caught fish in the east China sea. J. Hazard. Mater. 419, 126456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126456 (2021).

Justino, A. et al. The role of mesopelagic fishes as microplastics vectors across the deep-sea layers from the Southwestern Tropical Atlantic. Environ. Pollut. 300, 118988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.118988 (2022).

Choi, D., Gredzens, C. & Shaver, D. Plastic ingestion by green turtles (Chelonia mydas) over 33 years along the coast of Texas, USA. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 173, 113111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.113111 (2021).

Duncan, E. et al. Plastic pollution and small juvenile marine turtles: A potential evolutionary trap’. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 699521. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.699521 (2021).

Rodríguez, Y. et al. Litter ingestion and entanglement in green turtles: An analysis of two decades of stranding events in the NE Atlantic. Environ. Pollut. 298, 118796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.118796 (2022).

Bourne, W. R. P. & Imber, M. J. Plastic pellets collected by a prion on Gough Island, Central South Atlantic ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 13, 20–21 (1982).

Lavers, J., Hutton, I. & Bond, A. Temporal trends and interannual variation in plastic ingestion by flesh-footed shearwaters (Ardenna carneipes) using different sampling strategies. Environ. Pollut. 290, 118086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118086 (2021).

Navarro, A. et al. Microplastics ingestion and chemical pollutants in seabirds of Gran Canaria (Canary Islands, Spain). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 186, 114434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114434 (2023).

Expósito, N., Rovira, J., Sierra, J., Folch, J. & Schuhmacher, M. Microplastics levels, size, morphology and composition in marine water, sediments and sand beaches. Case study of Tarragona coast (western Mediterranean). Sci. Total Environ. 786, 147453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147453 (2021).

Expósito, N. et al. Levels of microplastics and their characteristics in molluscs from North-West Mediterranean Sea: Human intake. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 181, 113843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113843 (2022).

Carrillo, M. S. et al. Microplastic ingestion by common terns (Sterna hirundo) and their prey during the non-breeding season. Environ. Pollut. 327, 121627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121627 (2023).

Gallo, F. et al. Marine litter plastics and microplastics and their toxic chemicals components: The need for urgent preventive measures. Environ. Sci. Eur. 30, 13 (2018).

Gandara e Silva, P. P., Nobre, C. R., Resaffe, P., Pereira, C. D. S. & Gusmão, F. Leachate from microplastics impairs larval development in brown mussels. Water Res. 106, 364–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2016.10.016 (2016).

Rendell-Bhatti, F. et al. Developmental toxicity of plastic leachates on the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus. Environ. Pollut. 269, 115744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115744 (2021).

Bucci, K., Bikker, J., Stevack, K., Watson-Leung, T. & Rochman, C. Impacts to larval fathead minnows vary between preconsumer and environmental microplastics. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 41, 858–868. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5036 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the support of Patricia Rubio and Alejandro Vilas during the pellets micronization process and sea-urchin bioassays. We would also like to express our gratitude to the NGO Per La Mar Viva from Menorca Island for their assistance in the conducted samplings. Furthermore, this endeavor would not have been possible without the support of the volunteers from Good Karma Projects, to whom we also extend our thanks.

Funding

This study was supported by The RESPONSE project, founded by the “Joint Programming Initiative Healthy and Productive Seas and Oceans, “JPI Oceans” (PCI2020-112110) through the national funding agencies of Spain (Spanish National Research Agency). Pellet samples were collected during the MEDPELLETS (Status and dynamics of pellet contamination in the Western Mediterranean Sea) led by Good Karma Projects with the collaboration of Fundación Biodiversidad, under the Ministry of Transición Ecológica y Reto Demográfico, through Pleamar Program, co-financed by the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Michele Ferrari: writing–original draft, laboratory and data analysis methodological application, graphical representations, writing–review & editing. Filipe Laranjeiro: conceptualization, writing–original draft, laboratory and data analysis methodological application, graphical representations, writing–review & editing. Marta Sugrañes: sampling and samples processing, writing–review & editing writing. Jordi Oliva: writing–review & editing, funding acquisition. Ricardo Beiras: conceptualization, supervision, writing–review & editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrari, M., Laranjeiro, F., Sugrañes, M. et al. Weathering increases the acute toxicity of plastic pellets leachates to sea-urchin larvae—a case study with environmental samples. Sci Rep 14, 11784 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60886-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60886-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Understanding Microplastic Pollution in Riverbed Sediments: Special Emphasis on a Medium-Sized City in the State of São Paulo, Brazil

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2025)

-

Environmental consequences of interacting effects of changes in stratospheric ozone, ultraviolet radiation, and climate: UNEP Environmental Effects Assessment Panel, Update 2024

Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences (2025)