Abstract

The Silurian–Devonian transition played a crucial role in the development of early terrestrial ecosystems due to the rapid diversification of early vascular plants. However, records of Pridolian plants in western Gondwana are scarce, limited to outcrops located in southern Bolivia. In this contribution, an association of fossil plants housed in the Rinconada Formation is presented. This association corresponds to primitive fossil flora with reproductive structures and sterile axes linked to basal tracheophytes. The fossil assemblage is composed of Aberlemnia caledonica, Caia langii Cooksonia cf. cambrensis, C. paranensis, C. cf. pertoni, Hostinella sp, Cf. Isidrophyton sp, Salopella marcensis, Steganoteca striata, two morphotypes of doubtful taxonomy, and graptolites colonies. The association between flora remains and graptolites, represents a parautochthonous assemblage in an inner marine platform, dominated by gravity flows. This record has paleophytogeographic importance indicating the extension of the northwest Gondwana-southern Laurusia unit to more southern areas of Gondwana. This expansion would have been favored by the post-glacial climatic improvement of the Late Silurian, together with a great radiation capacity and environmental flexibility of the flora. Furthermore, the biochron is extended of three taxa (A. caledonica, C. paranensis and Cf. Isidrophyton sp) first known from the Lochkovian, to the Pridoli.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The settlement on the continent by the early land plants would have taken place during the Early Paleozoic This is based on the first appearance of cryptospores and trilete spores from early embryophytes, and the first record of spore-bearing fertile structures during the Darriwilian-Hirnantian1,2,3,4

Late Silurian and Early Devonian are critical times for primitive land plants radiation5,6,7,8. The fossil record of this time is scarce and restricted to paleotropical environments9. However, in recent decades numerous records of land plants in Gondwana high paleolatitudes have been released10,11,12,13,14,15.

Late Silurian phytogeography is crucial for understanding the global diversity and palaeoecology of early land plants, and also, may yield information concerning the palaeogeography and palaeoclimate of this interval. In addition, the study of late Silurian phytogeography may elucidate the pathway of land-plant radiation during the Silurian-Devonian boundary.

The fossil record of early tracheophytes of Pridolian age is abundant and well known in lower paleolatitudes16 and17 presented an excellent summary on the distribution of Silurian flora, with specimens found in China18, United States19, Canada19,20, Czech Republic21,22,23,24 United Kingdom25,26,27,28, Poland29, Ukraine30, Libya10, Kazakhstan16,31,32, and Australia33,34. In South America, a probable Pridolian age flora was found in Bolivia, nevertheless there are no index faunas to give a more accurate age12. However, megafloras of this age have not been reported in Argentina until now.

This contribution presents the first record of basal tracheophytes of early Pridolian age from Argentina, in the Rinconada Formation, Eastern Precordillera, San Juan province. The fossil assemblage is dated due to the presence of the Skalograptus parultimus Zone in the bearing strata35. This finding makes it possible to discuss the phytogeographic proposals for early tracheophytes and extend their scope to southwestern areas of Gondwana during the late Silurian.

Silurian phytogeography

The distribution of primitive floras has been a matter of interest, particularly during the Late Silurian period. This is because it is during this time interval that the configuration leading to the Devonian and upper Paleozoic floras is set36.

In recent years, several authors have conducted studies on Silurian phytogeography, combining macrofossil and palynological data with statistical analysis36, and cites therein]. Raymond16 grouped the distribution of early land plants during the Late Silurian into four phytogeographic units for the Pridoli: South Laurussian-North West Gondwana (SL-NG); North Laurussian (NL); Kazakhstan (K); and East Gondwanian (EG). The authors used land plant macrofossils to represent the taxa in each paleophytogeographic zone. The SL-NG unit is characterised by the prevalence of rhyniophytas and rhyniophytoides, which are found in a temperate climatic zone. The NL unit is distinguished by the preponderance of basal licophytes, which are situated in the vicinity of the paleoequatorial zone. The K unit is characterised by zosterophylls and rhyniophyte genera, which were established in a subtropical zone15. The EG unit is situated close to the paleoequator and is characterised by zosterophylls and basal lycopsids16. The authors conclude that phytogeographic differentiation is related to climate and palaeogeographic isolation.

Wellman7 established a database integrating palynological (principally trilete spores) and megafossil evidence. For the complete Silurian series, they delineated the following palaeogeographical localities: southwestwestern Gondwana; Peri-Gondwanan terranes; Avalonia; Arabian Plate; Laurentia; Eastern Gondwana; Baltica; South China Plate and Northern Gondwana. It was concluded that there was a tendency for phytogeographical differentiation from the Llandovery to the Pridoli between Gondwanan and North American/Baltic localities. Furthermore, Wellman7 highlighted the differences between analysis based on spores and those based on plant megafossils. In a recent study, Capel36 conducted an analysis of Silurian-Devonian plant genera across major palaeogeographical regions, integrating multivariate statistical analysis [for detailed methodology, see36]. Their findings revealed that Laurussian diversity patterns align with global trends, whereas regions like Gondwana and South China exhibited notable underrepresentation, potentially influencing interpretations. With regard to the Late Silurian period, the authors were able to ascertain that the South Laurussia-West Gondwana regions, which were dominated by rhyniophytoids, could be correlated with cooler climatic conditions. In contrast, the equatorial to mid-latitude zones were characterised by the presence of zosterophylls, which were linked with more warm to hot climatic conditions.

Silurian flora in Argentina

The presence of primitive flora in Argentina is well known in Devonian successions37,38,39,40. However, the record of Silurian vascular plants is scarce, limited to outcrops in Northwestern Argentina13. This flora was found in the upper levels of the Lipeón Formation, exposed in the Subandinas Range of Salta Province. The authors recognized a low-diversity association consisting mainly of fragmentary plant remains, isolated sporangia, and better preserved remains assigned to Hostinella sp., Cooksonia sp., and cf. Tarrantia. Aris13 supported a Ludlovian age for this paleoflora due the presence of Andinodesma sp. cf. A radicostata. However, this chronological assignment is conflictive given: (1) the taxon is not found in the flora-bearing beds; (2) Andinodesma presents an extensive biochron, also recorded in Devonian (Lochkovian) successions; (3) the taxon is not accompanied by other guide taxa that allow delimiting the beds carrying the flora to the Ludlow.

The Lipeón Formation outcrops to the north into Bolivian territory and takes the name of Kirusillas Formation41. In the latter, Morel et al.11 reported the first early tracheophytes with reproductive structures in South America. The authors recognized axes with isotomic branching that culminate in terminal sporangia, assigned to Cooksonia cf. caledonica42. Subsequently, Edwards et al.12 reported in the Lipeón Formation typical sterile axes of the genus Hostinella, non-rhyniophytoid axes with variable diameters probably belonging to algae, axes with dichotomous branching that culminate in terminal sporangia similar to Cooksonia. cf. caledonica, and isolated sporangia with forms assignable to cf. Tarrantia, cf. Cooksonia cambrensis, cf. Cooksonia hemisphaerica and C. pertoni.

In contrast, the Silurian microflora record in Argentina is well known. In the Precordillera, the Tucunuco Group43 has been extensively studied44,45,46,47. This group includes the La Chilca and Los Espejos formations43, which make up two transgressive–regressive siliciclastic sequences. These units are carriers of palynomorphs between the upper Hirnantian-lower Lochkovian interval, and recognize the Silurian-Devonian boundary in this succession46.

The presence of Pridolian palynomorphs in the Precordillera has been the subject of doubt over the years. Rubinstein49, proposed a Ludlow-Pridoli? age for the top of the Los Espejos Formation. However, this age was later discarded by44, suggesting that reliable palynological data to suggest Pridolian ages are absent.

More recently, García-Muro et al.48,50 reveals for the Los Espejos Formation the biozones LP (Synorisporites libycus-Lophozonotriletes poecilomorphus), RS (Chelinospora reticulata-Chelinospora sanpetrensis), and Subzone H (Chelinospora hemiesferica), originally recognized by51 in the upper Silurian of Spain. These biozones would indicate a Ludlovian-early Pridolian age50. In addition, the authors reported the existence of the TS Biozone (Synorisporites tripapillatus-Apiculiretusispora spicula)52, indicating an early Pridolian-Lochkovian age.

Paleogeographically, the marine phytoplankton of the La Chilca and Los Espejos formations show a cosmopolitan distribution, sharing species with Avalonia, Baltica, Laurentia, Armorica, and other Gondwanian regions47,53; while the terrestrial palynomorphs from the Los Espejos Formation show affinities with Gondwanian regions like Brazil and North Africa47,54.

In Northwestern Argentina, in the Zenta Range, two assemblages of Pridolian palynomorphs were reported by55 and56 for the Lipeón and Baritú formations. The first unit is bearer of an association, made up of acritarchs: Crassiangulina variacornuta; chitinozoans: Ancyrochitina fragilis, Angochitina sinica, Angochitina cf. filosa, Eisenachitina cf. bohemica, Margachitina cf. saretensis; chlorophytes: Quadrisporites variabilis, Quadrisporites granulatus cf. blanca; spores: Ambitisporites avitus, Amicosporites sp.; prasinophytes: Duvernaysphaera55,56. This association suggests an Aeronian (middle Llandovery) to a Pridolian-Lochkovian age55. The second association, first assigned to the Lipeón Formation55 and then to the Baritú Formation56, is made up of acritarchs: Crassiangulina variacornuta, Diexalophasis denticulate, Goniosphaeridium cf. uncinatum, Leiofusa banderillae, Onondagaella asymmetrica, Synsphaeridium sp, Verhyachium brave, Verhyachium downier; chitinozoans: Angochitina chlupaci, Angoschitina sinica, Conochitina papchycephala, Desmochitina sphaerica, Eisenachitina cf. bohemica; chlorophytes: Quadrisporites variabilis; criptospores: Dyadospora murusattenuata; spores: Cheilotetras sp., Imperfectotriletes sp.55,56.

Recently, Césari et al.57 described the first record of Silurian palynomorphs in the Famatina System, Villacorta Formation, La Rioja Province. The palynological assemblage is composed of terrestrial miospores (e.g. Artemopyra radiata, Cheilotetras caledonica, Dyadospora murusdensa, Gneudnaspora (Laevolancis) chibrikovae, Imperfectotriletes vavrdovae, Pseudodyadospora petasus, Rimosotetras problematica, Tetrahedraletes grayae, T. medinensis, Ambitisporites avitus/dilutus, Ambitisporites cf. A. eslae, Apiculiretusispora cf. Apiculiretusispora asperata, Apiculiretusispora sp., cf. Brochotriletes sp., Emphanisporites protophanus, Scylaspora scripta and S. vetusta) and nematophyte remains (Cosmochlaina). The biochronostratigraphic range of the species allowed the authors to propose a Wenlockian-Ludlovian age for the Villacorta Formation.

Geological settings

The Rinconada Formation is a sedimentary succession of 550 m thick35 that outcrops on the eastern margin of the Argentine Precordillera, in the Villicum, Chica de Zonda, and Pedernal ranges (Fig. 1). Lithologically, it is characterised by a sedimentary mélange, composed of blocks of various sizes, mainly of limestones, black shales, quartzites, and conglomerates, surrounded by a clastic matrix formed by conglomerate lenses, sandstones, and shales that shows a strong synsedimentary deformation. The base of the unit varies depending on the geographical location: in the Villicum Range it is overlying the Don Braulio Formation in an erosive unconformity58, in the Chica de Zonda Range, it rests unconformably over the Ordovician limestones of the San Juan Formation59, and finally, in the Pedernal Range, it covered the possible Don Braulio Formation60. Regarding its upper contact, it is generally covered by Neopaleozoic or Quaternary deposits in all localities (Jejenes and Loma de Las Tapias formations, or piedmont deposits).

Map of the distribution of the Rinconada Formation at the Chica de Zonda Range showing its geographical distribution, the upper and lower contacts and the distribution of the olistoliths. Red star shows the place where samples were collected. Satellite images were obtained using the free software SAS.Planet v.221122.10312 Nightly, source Bing Maps. QGIS 3.30.0-'s-Hertogenbosch was used for image processing and the layout of the geological features. The final assembly of the figure was carried out using the free software Inkscape v.1.3.2.

The relevant area is located in the eastern margin of the Chica de Zonda Range, San Juan, Argentina (Fig. 1). The section is 550 m thick with a lower fault contact, which runs in a N–S direction, while its top is covered by Quaternary sediments (Fig. 2). The fossiliferous level is located 350 m from the base, lodged in the matrix that is superimposed on a calcareous olistolith (Fig. 2).

Age of the Rinconada formation

The age of the Rinconada Formation is controversial given the sedimentary complexity of the mélange. The age data obtained over the years come mainly from the fossiliferous content collected both from the olistoliths and from the matrix. Several authors have contributed to the resolution of this problem, but there is still no consensus in the geological community. The paleontological content of the Rinconada formation is made up mainly of marine invertebrates, from the matrix and olistoliths. In particular, specimens of brachiopods, graptolites, plants and conodonts, have been described in the matrix of the unit, assigning a Wenlockian to early Devonian age35,59,61,62,63. On the other hand, fauna described from the olistoliths reported a Lower Ordovician (or older) to lower Silurian (Llandovery) age59,64,65.

Material and methods

The paleofloristic assemblage comes from the top of the Rinconada Formation at the homonymous section (Fig. 1). The fossil plants are preserved in a green sandstone, accompanied by colonies of graptolites of early Pridolian age (Fig. 2)35. The paleofloristic specimens occur as carbonaceous impression-compression. The specimens were observed with a binocular stereo microscope Leica S9D and photographed with a Leica Flexcam C1 camera. In cases requiring mechanical preparation, needles and a microjack-type pneumatic hammer were used. The descriptions were made using the criteria of66,67,68,69. The paleobiogeographic distribution of the Rinconada Formation fossil assemblage was modelled using the methodology proposed by16. All of the specimens are housed in the collection of the “Instituto y Museo de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de San Juan” under the acronym PBSJ.

Results

Systematic paleobotanical

Embryophyta Endlicher 1836, emend. Lewis and McCourt 2004.

Polysporangiophyta Kenrick and Crane, 1997.

Genus: Aberlemnia Gonez and Gerrienne, 2010.

Type Species: Aberlemnia caledonica (Edwards) Gonez and Gerrienne, 2010.

Aberlemnia caledonica (Fig. 3a–c).

(a–c) Aberlemnia caledonica. (a) Specimen PBSJ-1770. (c) Specimen PBSJ-1771. (b) detail drawing of (a) showing the last section of the subtending axe and the sporangium-axis concave junction (yellow arrow). (d, e) Cooksonia paranensis. (d) Specimen PBSJ-1766 showing the compression. (e) Drawing of (d), showing the sporangium-axis junction (red arrow) and the sporangial chamber (yellow arrow). (f–h) Cooksonia cf. pertoni. (f–g) specimens PBSJ1767 and PBSJ-1768 showing a coalified trumpet-shape sporangium. (h) Drawing of (g), showing the sporangial chamber (red arrow) and the operculum (yellow arrow). (i, j) Cooksonia cf. cambrensis. (i) specimen PBSJ-1769 showing the junction sporangium-axis (red arrow). (j) Drawing of the specimen PBSJ-1769 reconstructing the missing section of the sporangium (dotted line). Scale bars: 1 mm.

Description: The specimens consist of isolated carbonaceous compression of the sporangia and the proximal part of the sporangia axes. The axes are on average 0.94 mm wide, widening towards the sporangium base. The sporangia are oval to reniform in front view, bilaterally symmetrical. The sporangia has a mean width of 2.1 mm and 1.75 mm in height. The sporangium-axis junction is marked by a concave-downward line between the two structures. Nevertheless, this feature is well preserved in only one specimen.

Repository: PBSJ 1770–1771.

Remarks:70 excluded Cooksonia caledonica from the genus Cooksonia and erected the genus Aberlemnia, naming the type species of the genus A. caledonica based on the number of sporangium per axis, the sporangium bearing axes widening just before the sporangium-axis junction, a well-defined concave downward curve in the sporangium-axis junction, the shape in the front view of the sporangium (oval, circular or reniform), sporangia formed by two valves attached in their proximal part, and a dehiscence line that meets the sporangium outline at the axis-sporangium junction. Although the Rinconada Formation specimen is a single sporangium with the last part of the axis preserved, most of the characters outlined for the genus Aberlemnia were recognized. In addition, the general morphology and measurements of the Rinconada Formation specimen are consistent with the description of the species A. caledonica (Edwards)70. That is why we decided to name our material Amberlemnia caledonica.

Genus: Cooksonia (Lang, emend. Gonez & Gerrienne, 2010).

Type Species: Cooksonia pertoni Gonez & Gerrienne, 2010.

Cooksonia paranensis (Fig. 3d,e).

Repository: PBSJ 1766.

Description: The specimen comprises one coalified compression composed of a sporangia-bearing axe with an apical sporangium. The complete specimen is 6.55 mm in length, the axis is smooth, 5.35 mm in length and 0.7 mm wide, widening upward, marking the axis-sporangium transition progressive. The sporangium is partially preserved, cup-shaped in outline and measures 4.37 mm wide and 1.97 mm in height. The apical part of the sporangium is concave, because of the absence of the operculum.

Remarks: The general characteristics of the Rinconada Formation specimen matches most of the species Cooksonia paranensis71. Compared with C. pertoni, the transition between the axis and the sporangium is clear-cut in the type species while in C. paranensis this transition is more gradual. The sporangium in C. pertoni varies from shallowly funnel-shaped to discoidal, in C. paranensis, the sporangium is cup-shape. Compared with Aberlemnia caledonica described above, the sporangium of C. paranensis is cup-shape, in A. caledonica, sporangium ranges from sub-circular, oval to reniform shape. In addition, sporangium of C. paranensis is considerably larger than A. caledonica sporangium. This comparison also includes Cooksonia cf. caledonica from the Silurian of Bolivia12 that would be identified as A. caledonica by70. Habgood et al.72 described a new species of Cooksonia named C. banskii, from the Lower Devonian of Welsh. This specimen was later transferred to the species Concavatheca banskii by73. Concavatheca banskii comprises a single sporangium on smooth axes, nevertheless, there is a significant difference in size from the Rinconada Formation specimen. The specimen here described and compared, has morphological similarities with C. pertoni, C. paranensis and C. banskii. From these, the gradual transition between the sporangium and the subtending axes, as well as the cup-shaped of the sporangium are reminiscent of C. paranensis and C. banskii. Gess and Prestianni9 point out that the main difference between Concavatheca banskii and Cooksonia paranensis is related to preservation, which is allowed by the nomenclatural code (Art. 11.1, Shenzhen Code). Until the connection between the two is clarified and given that our samples are preserved as impression-compressions, here we name the material from La Rinconada as Cooksonia paranensis.

Cooksonia pertoni (Lang, emend. Gonez & Gerrienne, 2010).

Cooksonia cf. pertoni (Fig. 3f–h).

Repository: PBSJ 1767–1768.

Description: The specimens comprise two isolated sporangia and the last section of the axis-sporangium junction, all preserved as lateral compressions. The axis is 0.38 mm wide and 1.14 mm in length, and the junction axis-sporangium is transitional, with the axis widening upwards. The sporangia are trumpet-shaped, 1.77 mm wide, and 1.25 mm in length. Both specimens have a distal flattening towards the lateral top of the sporangia.

Remarks: Most of the characters named by70 for the sporangia of Cooksonia pertoni are present in the specimens from the Rinconada Formation. Despite the incomplete nature of the Rinconada specimens, we could compare our specimen sporangia with most of the genus Cooksonia. Sporangia of C. cambrensis and C. hemisphaerica do not have a trumpet-shaped form. In C. crassiparietilis, the shape of the sporangia is bivalve. C. paranensis has cup or bowl shape sporangia and a more gradual transition sporangium-axes than C. pertoni. Other species of the genus Cooksonia, such as C. banski were transferred to the genus Concavatheca73, because of the type of preservation so is not considered in this comparison. C. bohemica, comprises one sporangium with lousy preservation and is not taken into account for comparison. Also, C. caledonica, recently transferred to the genus Aberlemnia was not taken into account because the sporangia characters differ from the genus Cooksonia70. Nevertheless, we decide to name our materials C. cf pertoni because of the incomplete preservation of the two specimens. A most accurate nomination will be precise when more complete specimens are collected.

Cooksonia cambrensis (Lang, emend. Gonez & Gerrienne, 2010).

Cooksonia cf. cambrensis (Fig. 3i,j).

Repository: PBSJ 1769.

Description: The specimen consists of an isolated coalified compression constituted by the last section of a narrow axe and a sporangium in apical position. The complete structure is 2.00 mm in length. The axe is 0.29 mm wide, widening upwards near the junction sporangium-axes. The sporangium-axes contact is narrow, abrupt, and well marked by a black line, probably due to a thick walled-cell zone. The sporangium is more or less circular in outline, measuring 1.02 mm wide, and 0.74 mm high.

Remarks: The specimen from the Rinconada Formation displays the majority of the characters elected by25 to characterize Cooksonia cambrensis, such as the circular sporangium shape and a narrow sporangium-axis junction. However, due to the fragmentary nature of Rinconada Formation specimen, some features, like the type of branching and the circular outline of the sporangium, were not preserved. In light of the incomplete specimen described herein, we propose that the most appropriate designation for our specimen would be Cooksonia cf cambrensis. A more accurate nomination will be precise when more complete specimens are collected. Our specimen differs with C. banskii and C. hemisphaerica in the sporangium-axis junction, being transitional in both species and narrow and abrupt in C. cambrensis and Rinconada’s plant. Also, while C. cf. cambrensis sporangium outline is circular, C. banskii bears a sunken U-shape sporangial cavity, and C. hemisphaerica sporangium outline is globose. C. pertoni differs with having a flat-sided trumpet shape sporangium and a gradual transition between the axis and the sporangium. Sporangia preserved in C. paranensis71 (plate or bowl shaped with flat apical surface), C. bohemica24 (ranging from reniform to elliptical) and C. crassiparietilis70,74 (reniform, bivalvate, with a thick distal dehiscence line) allow to discard the assignment of Rinconada specimen to these species.

Genus: Salopella Edwards and Richardson, 1974.

Type species: Salopella allenii Edwards and Richardson, 1974.

Salopella marcensis (Fig. 4a,b).

(a, b) Salopella marcensis. a, coalified compression of specimen PBSJ-1763. (b) Detail of sporangia. (c–e) Steganotheca striata. (c) General aspect of specimen PBSJ-1765. (d) Detail of the top of the sporangia. (e) drawing of d showing the apical plateu broken (yellow arrow) and two possible striations (red arrow). (f) Isidrophyton sp. coalified impression of specimen PBSJ-1772 with two terminal sporangia (yellow arrow). Scale bars: 1 mm.

Repository: PBSJ 1763.

Description: Plant fragment with at least one dichotomy. The principal axe is at least 2.88 mm high, and the secondary axe is 2.92 mm high with two elongated terminal sporangia. Sporangia are elliptic, parallel-sided, isotomously branched, with blunt apices, 0.50 mm wide and 1.40 mm height. The sporangia are attached only at the base. The angle between sporangia is 30°.

Remarks: This specimen is assigned to Salopella marcensis67 on the base of dichotomously branched axes, which terminate in two large fusiform sporangia. The Rinconada specimen has only one angle preserved between the first and the second order axes of 90°, as reported by73. In comparison, S. allenii differs from the new material in its sporangial greater size and smaller branching angle. S. xinjiangensis from the Pridoli of northwest China is poorly known75. Several species of Salopella-type have been described from the upper Silurian-Lower Devonian from central Victoria, Australia. S. australis has one sporangium per daughter axe. In the Rinconada specimen, there are two sporangia per daughter axe. Also, S. australis sporangia size is five times longer and three times wider than Rinconada materials. Compared to S. caespitosa, the size of axes and sporangia are greater than S. marcensis; also the secondary dichotomy that leads to the sporangia is longer in S. caespitosa. Adittionally, the sporangia of S. caespitosa has a constriction near the apical part that is not present in S. marcensis. S. ladiae has branching angles acute (15°-50°) whereas S. marcensis has branching angles between 35°-90°. Furthermore, sporangia in S. ladiae are both height and wider than S. marcensis.

Genus Steganotheca.

Type species: Steganoteca striata Edwards, 1970.

Steganoteca striata (Fig. 4c–e).

Repository: PBSJ 1765.

Description: The unique specimen is preserved as a coalified compression. The whole structure comprises the last part of the subtending axe and a terminal sporangium. The complete structure measures 9.83 mm in length. The axe is parallel sided with a central black line, probably due to a thick walled-cell zone. The axe has a constant width (0.37 mm), widening upwards near the sporangium-axe junction. The sporangium measures 6.00 mm in length and gets wider (0.75 mm base; 1.19 middle; 1.20 mm top) towards the apex near the sporangium tip. The transition between the sporangium and the subtending axe is smooth. The tip of the sporangium is truncated and topped by a lens-shaped apical plateau. This structure measures 1.62 mm length and 0.25 mm width.

Remarks: The specimen from the Rinconada Formation displays most of the characteristics of the species Steganotheca striata, such as mug-shape sporangia characterized by a smooth axe-sporangia junction, sporangia longer than wide, and sporangia truncated to the apex by a lens-shaped plateau. However42, and66 described an oblique striation on the sporangia surface; this is the only character not preserved in Riconada’s Formation specimen, probably due to taphonomic bias. Despite the lack of striation, we consider that the similarities are sufficient to name the Rinconada Formation specimen as Steganotheca striata.

Isidrophyton Edwards et al., (2001).

Cf. Isidrophyton sp. (Fig. 4f).

Repository: PBSJ 1772.

Description: The single specimen consists of a coalifed, incomplete compression of 6.21 mm. The specimen comprises a main axis of 0.37 mm wide and a possible ramification near the sporangia. The principal axe ends in two short secondary axes, isotomously branching 0.16 mm wide with two terminal sporangia. The sporangia are in pairs, ellipsoidal 0.42 mm wide and 0.35 mm length, and the angle between the two sporangia is 80°.

Remarks: Isidrophyton is a monospecific genus described for the Lower Devonian of Villavicencio Formation37, defined by having a principal axis that branches isotomously with a single ellipsoidal sporangium in each branch immediately above the dichotomy, features shared by the Rinconada Formation specimen. On the other hand, our specimen lacks the fusiform longitudinally structures that cover the axes and is considerably smaller both in vegetative and reproductive traits than the type species I. iñiguezii, thus we prefer to name the Rinconada Formation specimen as Cf. Isidrophyton sp., hoping to find more complete specimens for a correct taxonomic approach. Our specimen can be compared also with Cooksonia, Fozzia and Renalia. In Cooksonia (Lang, enmend Gonez and Gerrienne, 2010), the sporangia are trumpet-shaped, while in Isidrophyton sp. are elliptical. Fozzia minuta76, a monospecific taxon from the Emsian of Belgium, has lateral appendages along the axes, both vegetative and fertile. The fertile ones bear a pair of sporangia, semi-circular, semi-oval or fusiform in outline. Isidrophyton sp differs from F. minuta in the shape and size of the sporangia and the lack of lateral appendages. Renalia hueberi77 from the Lower Devonian of Battery Point Formation is a plant characterized by lateral dichotomous branches terminated in rounded to reniform sporangia. The fertile branches bear 1 to 4 sporangia and are scattered may be similar to Cf. Isidrophyton, although they differ in the position and number of sporangia.

Genus: Caia Fanning et al. (1990).

Type species: Caia langii Fanning et al. (1990).

Caia langi (Fig. 5a–c).

(a–c) Caia langi. (a) General aspect of the specimen PBSJ-1773 showing the isotomously bifurcation (yellow arrow). (b) Detail of the sporangium. (c) Drawing of (b), showing the sporangium and four conical emergencies at the apex (yellow arrows). (d) Hostinella sp. specimen PBSJ-1764, notice the isostomously branching axes (yellow arrow). (e, f) Morphotype A. (e), coalified compression of specimen PBSJ-1775. (f) Drawing of (e), showing the two sporangial-shaped structures (yellow arrows). (g, h) Morphotype B. (g), coalified compression of specimen PBSJ-1774. h, drawing of g, showing the bifurcation (red arrow) and the conical emergence at the apex of the sporangium (yellow arrow).

Repository: PBSJ 1773.

Description: The only specimen recovered comprises an incomplete coalified compression. The complete specimen is 7.35 mm long. It is composed of a principal axis 0.37 mm wide and bifurcates isotomously once. The axis has smooth and parallel sides. At the bifurcation, the axis increases its width and becomes two secondary axes. One of the secondary axes bears the coalified compression of a sporangium. There is a slight thickening at the base of the subtending axis and the sporangium. The sporangium is elongated, 2–3 times longer than wider, 0.54 mm wide and 1.51 mm long, with parallel sides. At the apex of the sporangium, there are four conical emergencies. Two emergencies are well preserved. The emergences have decurrent bases and are 0.11 mm wide and 0.14 mm long, all concentrated in the apex of the sporangium.

Remarks: The specimen from the Rinconada Formation presents most of the characters defined by26 for the monospecific genera Caia, such as smooth isotomously branching axes with terminal bifurcating sporangia, longer than wide, bearing conical emergences, as well as the dimensions of the Welsh specimens. Nevertheless, at the Rinconada Formation, only one specimen was preserved with one sporangium after the bifurcation of the subtending axes. In addition, the diagnosis of C. langii includes spore characters; in our specimen, we could not recover any spores, nevertheless we name the specimen as C. langii. In addition, several Silurian-Devonian genera bear sporangia with emergences. Compared with Pertonella27, its sporangia are plate-shaped and tranvesally disposed; in the Rinconada specimen, the sporangium is elongated. Also, Pertonella has two emergences, while in Caia langii, there are four emergences. Dutoita78 might have ornamented sporangia with emergences; nevertheless, better specimens are needed to compare. Horneophyton has sporangia that are considerably larger than our specimen79; it also shows four to five lobes with a columella inside the sporangia, a feature absent in the Rinconada Formation specimen. Eocooksonia sphaerica80 from the Pridoli of China has a border covering the central part of the sporangia, formed by a variable number of emergencies (from four to eight), but the general shape of the sporangia is spherical, while in C. cf langii the sporangium is elongated, and there is no distinction between the central region and the outlier region with emergencies that show E. spaherica. In the same outcrops of the Rinconada Formation, we described another sporangium with emergences on the apical side named Morphotype B. Compared with C. langii, Morphotype B sporangium has a conical shape and is smaller than C. langii.

Genus: Hostinella sp. Barrande ex Stur (1882).

Hostinella sp. (Fig. 5d).

Repository: PBSJ 1764.

Description: Specimens consist of incomplete carbonised compressions of smooth sterile axes. Some specimens bifurcate once, while others are just one single axe. Branching is isotomous, widening just before the branching point, and the branching angle varies from 40° to 95°. Principal axes are 0.64 mm wide and 9.80 mm long on average; nevertheless, the longest specimen recorded is 18.24 mm.

Remarks: Smooth isotomously branching axes are conventionally named Hostinella12. Coalified preserved axes like the Rinconada Formation specimens have no evidence of cellular preservation and thus may derive either from non-vascular plants or tracheophytes12. Gerrienne et al.71 proposed that naked axes could be assigned to the genus Tarrantia67 based on proximity; however, Tarrantia comprises axes as well as reproductive structures67. Considering this, solitary axes recovered from the Rinconada Formation are included in the genus Hostinella.

Morphotype A (Fig. 5e,f).

Repository: PBSJ 1775.

Description: The specimen consists of a small fragment with a principal axis of 0.53 mm width and 1.48 mm height. The principal axe bifurcates isotomously, finishing at the top in two sporangial-shaped structures. These structures are elliptical, 0.43 mm wide and 0.86 mm long, forming an angle between them of 28°.

Remarks: The specimen from the Rinconada Formation is fragmentary and lacks particular characters for proper taxonomic identification. The sporangial-shaped structures are identified as reproductive structures based on their apical position and elliptical shape. There are several examples of upper Silurian-Lower Devonian elongate sporangia with similar proportions12,26,66,67, none of which are similar enough to the Rinconada Formation specimen; a detailed comparison of such incomplete material is premature, so this specimen should remain unnamed.

Morphotype B (Fig. 5g,h).

Repository: PBSJ 1774.

Description: The single specimen consists of an incomplete coalified compression. The specimen is 4.00 mm long. The principal axis is 0.44 mm wide; it bifurcates at the top isotomously into two secondary axes of 0.24 mm wide each. One of the secondary axes ends in a sporangium, and the other is unclear. The sporangium in lateral view has a conical shape. It is 1.00 mm long and 0.50 mm wide; nevertheless, the transition between the secondary axe and the sporangium is smooth and not precise, as is the limit between both structures. The apical end of the sporangium is broad and has four minor emergencies. The emergencies are sharp at the apex, with decurrent bases 0.23 mm high and 0.15 mm wide.

Remarks: The Rinconada Formation specimen has several characteristics that fit numerous early plant descriptions. Nevertheless, the unique characteristics, such as the sporangium emergencies, are not typical for Silurian-Devonian floras. Compared to Pertonella27, the Rinconada specimen is considerably smaller, both in axis width and sporangium size; also, the emergences in Pertonella sporangia are two, rounded, and with a truncated top71. Gerrienne et al.71 also suggest that Pertonella from the Devonian of Brazil might have the same emergencies in the axes. This feature was not observed in the Rinconada specimen. The genus Dutoitia78 probably has ornamented axes and sporangia; however, illustrations are not very clear. Horneophyton sporangia are considerably larger than our specimen79, it also shows. four to five lobes, with a columella inside the sporangia, a feature absent in the Rinconada Formation specimen. Caia26 sporangia have a variable number of emergencies at the distal third of the sporangia. These emergencies are three to seven in number and have a blunt apex and decurrent bases. These characteristics are not present in our specimen. Recently, Xue et al.80 described Eocooksonia sphaerica from the Pridoli of China, with a border covering the central part of the sporangia, formed by a variable number of emergencies. E. spahaerica emergences are four to eight in number and more prominent on average than Rinconada Formation specimen emergences. The presence of emergencies in sporangia is a critical generic character in early land plants; nevertheless, the Rinconada Formation specimen is incomplete and only one in number. Despite the differences with the taxa mentioned above, we prefer to keep our specimen unnamed until more complete specimens are discovered.

Taphonomic features of the fossil assemblage

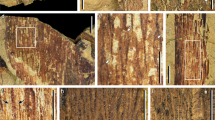

Flora remains were found in massive tabular sandstone strata with limited boundaries, grading up to narrow thin sandstone and shale beds, close to olistholite bodies (Fig. 6a–c). The plant specimens are abundant, with moderate state of preservation, mostly fragmentary. Isolated sporangia, connected to axes are randomly disposed all over the bedding planes. The taphonomic features analysis includes: degree of packing and relative orientation of the fossil assemblage, degree of fragmentation of the fossil plant remains, the presence of trace fossils (type) and the relative size of mica81.

(a) General view of the Rinconada Formation outcrops, showing the matrix (red arrow) and the olistoliths (white arrows). (b) Detail of (a), showing the bearing fossil strata (yellow scheme) and the olistolith over the matrix (red arrow). (c) Detail of synsedimentary deformation (red arrow). (d) orientation of the fossil plants (yellow arrows). (e–f) Skalograptus parultimus found in the same strata of the fossil plants. (g) Detail of the degree of fragmentation of the plant fossil assemblage and mica size (yellow arrows). (h) Trace fossils found in the same facies of the fossil plant strata, classified as Gordia isp. (i) Interpretation of the process that preserved together plants fossil and graptolites.

Regarding the paleofloristic assemblage of the Rinconada Formation, the fossil plant assemblage is densely to loosely packed with no relative orientation (Fig. 6d). The degree of fragmentation is partial, considering that the vast majority of the plant remains have connections between reproductive structures and subtending axes, and a certain amount of Hostinella sp. has several degrees of dichotomies (Fig. 6g). Samples display only horizontal trace fossils of the type classified as Gordia isp., and finally the size of mica regarding the fossiliferous planes is under 0.50 mm (Fig. 6g,h).

Considering the taphonomic features recognized above, the plant fossil assemblage was subjected to a lower sedimentation rate. The presence of horizontal trace fossils indicates low energy environmental conditions82. In addition, the trace fossils identified as Gordia isp. are interpreted as feeding or trace borrows which is a sign of higher concentration of organic material (plants) with a low sedimentation rate83,84,85,86,87. Finally, the fine grain size of mica (0.18–0.29 µm in average) found in the same facies, represents normal marine deposition in low energy environmental conditions81,88.

On the other hand, the graptolites are scarce and mainly present in two different astogenetic states: juvenile specimens (majority), with sicula and development of three to five thecae at most; and mature specimens (minority), which lack a proximal end preserved (Fig. 6e,f). It is worth mentioning that some juvenile colonies show a broken or not completely preserved sicula. As well as the associated plant remains, the graptolites are arranged randomly.

The mentioned juvenile-graptolite dominance might suggest a stressfull paleoenvironmental conditions, which would generally impede that the colonies reach mature astogenetic states. These faunal features in the graptolite assemblages, together with the sinsedimentary features of the host strata, allow to interpret the sedimentary deposition related to flows of fine grain materials coming in hyperpynic currents from the continent89. These flows would be loaded with flora remains and would trap planktonic organisms with subsequent deposition by decantation of the suspended load (Fig. 6i).

The fossil association between graptolites and plants remains preserved in the Rinconada Formation, represents a parautochthonous fossil assemblage [sensu90,91]. In a paleogeographic context, the gathering between graptolites and plant remains was relatively close to the source area, allowing the interpretation of the paleogeographic distribution of both fossil groups and the southward dispersion of Late Silurian floras. Furthermore, the lack of preferential orientation of the fossil plant could be the result of transportation mechanisms by suspension along the water surface81,92.

The Rinconada Formation is characterised by complex sedimentary features. According to93 the sedimentary paleoenvironment of the Rinconada Formation mélange corresponds to an inner marine platform, dominated by gravity flows in variable slope zones of the basin. The taphonomic features of the fossil association points to an inner marine platform, not far from the coast, where organic particles could decant in a relatively serene paleoenvironment dominated by gravity flows.

The fossil assemblage of the Rinconada Formation (plants and graptolites) is preserved in massive fine sandstone with no preferential orientation, partially fragmented and loosely packed. The sedimentary mechanisms that produce such arrangement are extrabasinal turbidity currents associated with lofting89. This process allows the direct transfer of organic matter (mainly plant remains) and sediments from the continent to inner basin shelves, mixing in the case of Rinconada Formation matrix, marine and continental fossils in the same facies.

Discussion and conclusions

The Pridolian flora of the Rinconada Formation is characterised by a low diversity association of Eutracheophytes. Taxa such as Aberlemnia (ex Cooksonia) caledonica, Cooksonia pertoni, and Hostinella. sp, have been reported in northern areas as Bolivia and Northwest of Argentina (NOA)11,12,13,70. The discovery of this flora in the Rinconada Formation and their similarity with the Bolivian and the Anglo Welsh Basin assemblage makes it possible to extend the geographical scope towards more southern areas of the phytogeographic unit of South Laurrusian-Northwest Gondwana16 (Fig. 7).

Paleogeographic reconstruction of the continents during the interval Ludlow-Pridoli. Map showing the distribution during, Ludlow (red star) and Pridoli (blue star), fossil assemblages and the Rinconada Formation fossil plants strata. NL = North Laurussian unit; K = Kazakhstan unit; NEG = Northeast Gondwana unit; SL-NWG = South Laurassia-Northwest Gondwana unit. Modified from97 and15.

The presence of A. caledonica and C. paranensis in the Pridolian beds of the Rinconada Formation, extends the biochron of these two taxa to the Pridoli, as well as the genus Cf. Isidrophyton, first described for the Lower Devonian of the Villavicencio Formation (Table 1). Considering that the brazilian taxa has now a Pridolian age, this (Table 1) triggers the question: How rhyniophytoids assemblages from South Laurrusian-Northwest Gondwana share so many genera when climatic conditions were different and both regions were separated by the Rheic Ocean?

The Ludlow-Pridoli interval is characterised by periods of global cooling denoted by variations in the carbon cycle, a positive excursion of δO18 and a fall in sea level15,94. This time interval of cold climate is known as the Middle Ludfordian Glaciation94. According to15, the fall in sea level result of the glacial event would have reconfigured the coastlines, leaving a narrower Rheic Ocean between Southern Laurassia and Northwest Gondwana. These conditions provided new emerging areas that would favour the dispersion of spores and would have functioned as suitable substrate (“soils”) with new reserves of nutrients, favouring the spreading habitats, and the consequently expansion of early land plants. As previously suggested by8, it is thought that early land plants were free-sporing homosporus that relied on wind and water for the distribution of spores. It is believed that adaptation as a small size, huge number of isospores, and the presence of resistant sporopollenin walls, allowed them to disperse through freshwater and near-shore environments, providing suitable conditions for dispersion and consequently preservation.

Furthermore, the facies of Rinconada Formation fossil assemblage are interpreted as an inner marine platform93, as well as the Lipeón Formation facies are interpreted as marginal marine environments95. Compared with the Pridolian fossil record of South Laurassia17,73, most of the plant fossil assemblages occur in coastal marine deposits. This could explain the distribution of Pridolian flora between South Laurasia and Northwest Gondwana across the Rheic Ocean and the paleophytogeography assemblage between these two regions16. The configuration of the different paleophytogeographic zones proposed by16 regarding the Rinconada Formation fossil assemblage is coincident with recent phytogeographic proposals for the Late Silurian. The configuration between South America and Avalonia, as proposed by8, during the Pridoli, is coincident with the distribution proposed here for the Rinconada Formation megafossil plants. Furthermore, the hypothesis of36 suggests that South Laurussia and West Gondwana are clustered together due to the presence of rhyniophytoids, which are also present in specimens from the Rinconada Formation, demonstrating the similarities between these regions.

The diversification of the flora during the regressive events would have been accentuated during the Pridoli, where a rapid climate change occurs from the cold conditions of the Ludfordian to super-greenhouse conditions96. The warm temperatures have favored the expansion and diversification of early land plants, denoted by an increase in the diversity of trilete spores producers15. Probably, the flora content of the Rinconada Formation results from the expansion towards the southernmost areas during the Pridolian, resulting from the progressive increase of the temperatures in extreme green-house conditions conforming part of the Initial Plant Diversification and Dispersal Event14. This paleoclimatic event, together with a wide dispersal capacity of the flora might have allowed it to populate these areas according to16.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript article.

References

Wellman, C. H., Osterloff, P. L. & Mohiuddin, U. Fragments of the earliest land plants. Nature 425, 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01884 (2003).

Rubinstein, C. V., Gerrienne, P., de la Puente, G. S., Astini, R. A. & Steemans, P. Early middle ordovician evidence for land plants in Argentina (eastern Gondwana). New Phytologist 188, 365–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03433.x (2010).

Salamon, M. A. et al. Putative late ordovician land plants. New Phytologist 218, 1305–1309. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15091 (2018).

Xu, H., Wang, K., Huang, Z., Tang, P., Wang, Y., Liu, B., & Yan, W. The earliest vascular land plants from the Upper Ordovician of China (2022).

Kenrick, P. & Crane, P. R. The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature 389, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/37918 (1997).

Steemans, P. et al. Origin and radiation of the earliest vascular land plants. Science 324(5925), 353–353 (2009).

Wellman, C. H. The classic lower devonian plant-bearing deposits of northern New Brunswick, eastern Canada: dispersed spore taxonomy and biostratigraphy. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 249, 24–49 (2018).

Wellman, C. H., Steemans, P. & Vecoli, M. Chapter 29 Palaeophytogeography of Ordovician–Silurian land plants. Geol. Soc. Lond. Memoirs 38(1), 461–476 (2013).

Gess, R. W. & Prestianni, C. An early Devonian flora from the Baviaanskloof formation (Table Mountain Group) of South Africa. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 11859 (2021).

Daber, R. Cooksonia-one of the most ancient psilophytes-widely distributed, but rare. Botanique (Nagpur) 2, 35–40 (1971).

Morel, E., Edwards, D. & Rodriguez, M. I. The first record of Cooksonia from South Americain Silurian rocks of Bolivia. Geol. Mag. 132, 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800021506 (1995).

Edwards, D., Morel, E. M., Paredes, F., Ganuza, D. G. & Zúñiga, A. Plant assemblages from the Silurian of southern Bolivia and their palaeogeographic significance. Bot. J. Linnean Soc. 135, 229–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2001.tb01093.x (2001).

Aris, M. et al. Primer registro de plantas silúricas en Argentina. Formación Lipeón, Área río Condado-río Los Toldos, Sierras Subandinas Occidentales (Provincia de Salta). Acta Geológica 23, 70–77 (2011).

Kraft, P., Pšenička, J., Sakala, J. & Frýda, J. Initial plant diversification and dispersal event in upper Silurian of the Prague Basin. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 514, 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.09.034 (2019).

Pšenička, J. et al. Dynamics of silurian plants as response to climate changes. Life 11, 906. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11090906 (2021).

Raymond, A., Gensel, P. & Stein, W. E. Phytogeography of late silurian macrofloras. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 142, 165–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2006.02.005 (2006).

Edwards, D. & Wellman, C. Embryophytes on land: The Ordovician to Lochkovian (lower Devonian) record. In Plants Invade the Land (eds Gensel, P. & Edwards, D.) 3–28 (Columbia University Press, 2001). https://doi.org/10.7312/gens11160-003.

Chong-Yang, C., Ya-Wei, D. & Edwards, D. New observations on a Pridoli plant assemblage from north Xinjiang, northwest China, with comments on its evolutionary and palaeogeographical significance. Geol. Mag. 130, 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800009821 (1993).

Edwards, D., Banks, H. P., Ciurca, S. J. & Laub, R. S. New Silurian cooksonias from dolostones of north-eastern North America. Bot. J. Linnean Soc. 146, 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2004.00332.x (2004).

Kotyk, M. Late Silurian and early Devonian fossil plants of Bathurst Island, arctic Canada (Master Thesis). University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada, p. 157 (1998).

Obrhel, J. Die Flora der Pridoli-Schichten (Budnany-Stufe) des Mittelböhmischen Silurs. Geologie 2, 83–97 (1962).

Schweitzer, H. J. Die Unterdevonflora des Rheinlandes. Palaeontographica B189, 1–138 (1983).

Kraft, P. & Kvaček, Z. Where the lycophytes come from? A piece of the story from the Silurian of peri-Gondwana. Gondwana Res. 45, 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2017.02.001 (2017).

Libertín, M., Kvaček, J., Bek, J. & McLoughlin, S. The early land plant Cooksonia bohemica from the Pridoli, late Silurian, Barrandian area, the Czech Republic, Central Europe. Hist. Biol. 35(12), 2504–2514 (2023).

Edwards, D. The early history of vascular plants based on late Silurian and early Devonian floras of the British Isles. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 8(1), 405–410 (1979).

Fanning, U., Edwards, D. & Richardson, J. B. Further evidence for diversity in late Silurian land vegetation. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 147, 725–728. https://doi.org/10.1144/gsjgs.147.4.0725 (1990).

Fanning, U., Edwards, D. & Richardson, J. B. A new rhyniophytoid from the late Silurian of the Welsh Borderland. Neues Jahrbuch Geologie Paläontologie Abh 183, 37–47 (1991).

Rogerson, C., Edwards, D. & Axe, L. A new embryophyte from the Upper Silurian of Shropshire, England. Studies in Palaeozoic Palaeontology and Biostratigraphy in Honour of Charles Hepworth Holland. Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 67, 233–249 (2002).

Bodzioch, A., Kozlowski, W. & Poplawska, A. A. Cooksonia-type flora from the Upper Silurian of the Holy Cross Mountains, Poland. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48, 653–656 (2003).

Ishchenko, T. The late Silurian flora of Podolia 1–80 (Institute of Geological Science, Academy of Science of the Ukrainian SSR, Kiev, 1975).

Senkevich, M. New Devonian psilophytes from Kazachstan. Esheg Vses Paleontol Obschestva 21, 288–298 (1975).

Senkevich, M. Fossil plants in the Tokrau horizon of the Upper Silurian. In The Tokrau Horizon of the Upper Silurian Series: Balkhash Segment (eds Nikitin, I. F. & Bandaletoc, S. M.) 236 (Alma-Ata, 1986).

Garratt, M. & Rickards, R. Pridoli (Silurian) graptolites in association with Baragwanathia (Lycophytina). Bull. Geol. Soc. Denmark 35, 135–139 (1987).

McSweeney, F. R., Shimeta, J. & Buckeridge, J. S. J. S. Two new genera of early Tracheophyta (Zosterophyllaceae) from the upper Silurian-Lower Devonian of Victoria, Australia. Alcheringa Austral. J. Palaeontol. 44, 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/03115518.2020.1744725 (2020).

Lopez, F. E. et al. First record of Pridolian graptolites from South America: Biostratigraphic and paleogeographic remarks. Gondwana Res. 119, 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gr.2023.03.026 (2023).

Capel, E. et al. The effect of geological biases on our perception of early land plant radiation. Palaeontology 66(2), e12644 (2023).

Edwards, D., Morel, E., Poiré, D. G. & Cingolani, C. A. Land plants in the Devonian Villavicencio formation, Mendoza Province, Argentina. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 116, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-6667(01)00059-8 (2001).

Cingolani, C. A., Berry, C. M., Morel, E. & Tomezzoli, R. Middle Devonian lycopsids from high southern palaeolatitudes of Gondwana (Argentina). Geol. Mag. 139, 641–649. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756802006957 (2002).

Arnol, J. A., Uriz, N. J., Cingolani, C. A., Abre, P. & Basei, M. A. S. Provenance evolution of the San Juan Precordillera Silurian-Devonian basin (Argentina): Linking with other depocentres in Cuyania terrane. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 115, 103766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103766 (2022).

Arnol, J. A. & Coturel, E. P. Early Devonian paleogeographic evolution of SW Gondwana (Precordillera Argentina). How can the record of plants help us?. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 114, 103680 (2022).

Ahlfeld, F. & Branisa, L. Geología de Bolivia 245 (Instituto Boliviano Petroleo, 1960).

Edwards, D. Fertile rhyniophytina from the lower Devonian of Britain. Palaeontology 13, 451–461 (1970).

Cuerda, A. Monograptus leintwardinensis var, incipiens Wood en el Silúrico de la Precordillera. Ameghiniana 4, 171–177 (1965).

Rubinstein, C. V. & García-Muro, V. J. Fitoplancton Marino de Pared Orgánica y Mioesporas Silúricos de la Formación los Espejos, en el Perfil del Río de las Chacritas, Precordillera de San Juan, Argentina. Ameghiniana 48, 618–641. https://doi.org/10.5710/AMGH.v48i4(491) (2011).

Rubinstein, C. V. & García Muro, V. J. Silurian to early Devonian organic-walled phytoplankton and miospores from Argentina: Biostratigraphy and diversity trends. Geol. J. 48, 270–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/gj.1327 (2013).

García-Muro, V. J. & Rubinstein, C. V. New biostratigraphic proposal for the lower Palaeozoic Tucunuco Group (San Juan Precordillera, Argentina) based on marine and terrestrial palynomorphs. Ameghiniana 52, 265–285. https://doi.org/10.5710/AMGH.14.12.2014.2813 (2015).

García Muro, V. J., Rubinstein, C. V., Rustán, J. J. & Steemans, P. Palynomorphs from the Devonian Talacasto and Punta Negra formations, Argentinean Precordillera: New biostratigraphic approach. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 86, 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2018.06.009 (2018).

García-Muro, V. J., Rubinstein, C. V. & Steemans, P. Palynological record of the Silurian/Devonian boundary in the Argentine Precordillera, western Gondwana. Neues Jahrbuch Geologie Paläontologie. Abh 274, 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1127/njgpa/2014/0438 (2014).

Rubinstein, C. V. Acritarchs from the upper Silurian of Argentina: Their relationship with Gondwana. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 8, 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-9811(94)00045-4 (1995).

García-Muro, V. J., Rubinstein, C. V. & Steemans, P. Upper Silurian miospores from the Precordillera Basin, Argentina: Biostratigraphic, paleoenvironmental, and paleogeographic implications. Geol. Mag. 151(3), 1–19 (2013).

Richardson, J., Rodriguez, R. & Sutherland, S. Palynological zonation of Mid-Palaeozoic sequences from the Cantabrian Mountains, NW Spain, implications for inter-regional and interfacies correlation of the Ludford/Přídolí and Silurian/Devonian boundaries, and plant dispersal patterns. Bull. Natl. Hist. Museum Geol. 57, 115–162 (2001).

Richardson, J. & McGregor, D. Silurian and Devonian spore zones of the Old Red Sandstone continent and adjacent regions. Memoirs Geol. Surv. Can. 364, 1–78 (1986).

García Muro, V. J., Rubinstein, C. V. & Martínez, M. A. Palynology and palynofacies analysis of a Silurian (Llandovery-Wenlock) marine succession from the Precordillera of western Argentina: Palaeobiogeographical and palaeoenvironmental significance. Mar. Micropaleontol. 126, 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marmicro.2016.06.002 (2016).

Rubinstein, C. & Steemans, P. Miospore assemblages from the Silurian-Devonian boundary, in borehole A1–61, Ghadamis Basin, Libya. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 118, 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-6667(01)00124-5 (2002).

di Pasquo, M., Vergel, M., Noetinger, S., Aráoz, L. & Aceñolaza, G. Estudios palinoestratigráficos del Paleozoico en Abra Límite, Sierra de Zenta, Provincia de Jujuy, Argentina. 18º Congreso Geológico Argentino, Actas, 1470–1471. Neuquén (2011).

Araoz, L., Noetinger, S., Vergel, M. & Di Pasquo, M. Bioestratigrafía, paleogeografía y paleoecología del Paleozoico de Sierra de Zenta, Cordillera Oriental Argentina. Serie Correlación Geológica 32, 43–64 (2016).

Césari, S. N. et al. The first upper Silurian land-derived palynological assemblage from South America: Depositional environment and stratigraphic significance. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 559, 109970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109970 (2020).

Peralta, S. & Carter, C. Don Braulio formation (late Ashgillian-early Llandoverian, San Juan Precordillera, Argentina): stratigraphic remarks and paleoenvironmental significance. Acta-Universitatis Carolinae Geologica 1–2, 225–228 (1999).

Peralta, S. Graptolitos del Llandoveriano inferior en el Paleozoico inferior clástico en el pie oriental de la sierra de Villicum, Precordillera Oriental. I Jornadas Sobre Geología de Precordillera, Actas 1, 59–66, San Juan, Argentina (1986).

Mestre, A. & Heredia, S. E. Paleozoico Inferior del borde oriental de la Sierra de Pedernal – Cienaguita, Precordillera Oriental. Serie Correlación Geológica 30, 5–12 (2014).

Amos, A. & Boucot, A. A revision of the brachiopod family Leptocoeliidae. Palaeontological Association, 440–461 (1963).

Benedetto, J. & Franciosi, M. Braquiópodos silúricos de las formaciones Tambolar y Rinconada en la Precordillera de San Juan, Argentina. Ameghiniana 35, 115–132 (1998).

Voldman, G. G., Alonso, J. L., Banchig, A. L. & Albanesi, G. L. Silurian conodonts from the Rinconada formation, Argentine Precordillera. Ameghiniana 54, 390–404. https://doi.org/10.5710/AMGH.20.12.2016.3039 (2017).

Voldman, G. G. et al. Tips on the SW-Gondwana margin: Ordovician conodont-graptolite biostratigraphy of allochthonous blocks in the Rinconada mélange, Argentine Precordillera. Andean Geol. 45, 399. https://doi.org/10.5027/andgeoV45n3-3095 (2018).

Lopez, F.E., et al. Olistoliths of the Gualcamayo formation (Middle Ordovician) embedded in the Silurian-lower Devonian Rinconada formation, Eastern Precordillera, Argentina: Paleontological, stratigraphic, and basin-model implications. Latin Am. J. Sedimentol. Basin Anal. https://lajsba.sedimentologia.org.ar/index.php/lajsba/article/view/239 (In press).

Edwards, D. & Rogerson, E. C. W. New records of fertile rhyniophytina from the late Silurian of Wales. Geol. Mag. 116, 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800042503 (1979).

Fanning, U., Edwards, D. & Richardson, J. B. A diverse assemblage of early land plants from the lower Devonian of the Welsh Borderland. Bot. J. Linnean Soc. 109, 161–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.1992.tb00264.x (1992).

Gonez, P. & Gerrienne, P. A new definition and a lectotypification of the genus Cooksonia Lang 1937. Int. J. Plant Sci. 171(2), 199–215 (2010).

Gonez, P., Huu, H. N., Hoa, P. T., Clément, G. & Janvier, P. The oldest flora of the South China Block, and the stratigraphic bearings of the plant remains from the Ngoc Vung Series, northern Vietnam. J. Asian Earth Sci. 43(1), 51–63 (2012).

Gonez, P. & Gerrienne, P. Aberlemnia caledonica gen. et comb. nov., a new name for Cooksonia caledonica Edwards 1970. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 163(1–2), 64–72 (2010).

Gerrienne, P., Bergamaschi, S., Pereira, E., Rodrigues, M.-A.C. & Steemans, P. An early Devonian flora, including Cooksonia, from the Paraná Basin (Brazil). Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 116, 19–38 (2001).

Habgood, K. S., Edwards, D. & Axe, L. New perspectives on Cooksonia from the lower Devonian of the Welsh Borderland. Bot. J. Linnean Soc. 139, 339–359. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1095-8339.2002.00073.x (2002).

Morris, J. L., Edwards, D., Richardson, J. B., Axe, L. & Davies, K. L. Further insights into trilete spore producers from the early Devonian (Lochkovian) of the Welsh Borderland, UK. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 185, 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2012.08.001 (2012).

Yurina, A. L. Devonian flora of central Kazakhstan. Materiely po geologii Shentral’nogo Kazakhstana 8, 1–208 (1969).

Yawei, D. & Zhehua, S. Devonian plants of Xinjiang. Palaeontological Atlas of Northwestern China 561–594 (1983).

Gerrienne, P. The Emsian plants from Fooz-Wépion (Belgium). III. Foozia minuta gen. et spec. nov., a new taxon with probable cladoxylalean affinities. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 74(1–2), 139–157 (1992).

Gensel, P. G. Renalia hueberi, a new plant from the lower Devonian of Gaspé. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 22, 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-6667(76)90009-9 (1976).

Anderson, G. & Anderson, H. Palaeoflora of Southern Africa. Prodromus of South African megafloras Devonian to Lower Cretaceous. Rotterdam, p. 423 (1985).

El-Saadawy, W.E.-S. & Lacey, W. S. Observations on Nothia aphylla Lyon ex Høeg. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 27, 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-6667(79)90037-X (1979).

Xue, J., Wang, Q., Wang, D., Wang, Y. & Hao, S. New observations of the early land plant Eocooksonia Doweld from the Pridoli (Upper Silurian) of Xinjiang, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 101, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2015.02.003 (2015).

de Oliveira Martins, G. P., da Costa Rodrigues-Francisco, V. M., da Conceição Rodrigues, M. A. & de Araújo-Júnior, H. I. Are early plants significant as paleogeographic indicators of past coastlines? Insights from the taphonomy and sedimentology of a Devonian taphoflora of Paraná Basin, Brazil. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 505, 234–242 (2018).

Buatois, L. & Mángano, G. Ichnology: Organism-substrate interactions in space and time 358 (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Gong, Y. M. Trace fossils of early-middle Devonian clastic formations in southwestern Hunan and their relation to sedimentary environments. Collect. Pap. Lithofacies Paleogeogr. 4, 98–116 (1998) (in Chinese with English Summary).

Aceñolaza, F. G. & Buatois, L. A. Nonmarine perigondwanic trace fossils from the late Paleozoic of Argentina. Ichnos 2, 183–201 (1993).

McCann, T. A Nereites ichnofacies from the Ordovician–Silurian Welsh Basin. Ichnos 3, 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/10420949309386372 (1993).

Yang, S. Trace fossils from early-middle Cambrian Kaili formation of Taijiang, Guizhou. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 33, 250–258 (1994).

Li, C. W., Chen, J. Y. & Hua, T. E. Precambrian sponges with cellular structures. Science 279, 879–882 (1998).

Irmis, R. B. & Elliott, D. K. Taphonomy of a middle Pennsylvanian marine vertebrate assemblage and an actualistic model for marin abrasion of teeth. Palaios 21, 466–479. https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2005.P05-105R (2006).

Zavala, C. & Pan, S. Hyperpycnal flows and hyperpycnites: Origin and distinctive characteristics. Lithol. Reserv. 30, 1–27 (2018).

Gastaldo, R. A., Pfefferkorn, H. W. & DiMichele, W. A. Taphonomic and sedimentologic characterization of roof-shale floras. Memoirs Geol. Soc. Am. 8, 341–352 (1995).

Kidwell, S. M., Fursich, F. T. & Aigner, T. Conceptual framework for the analysis and classification of fossil concentrations. Palaios 1, 228. https://doi.org/10.2307/3514687 (1986).

Bergamaschi, S. Análise sedimentológica da Formação Furnas na faixa de afloramentos do flanco norte do arco estrutural de Ponta Grossa, Bacia do Paraná, Brasil (Master Thesis). Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, p. 172 (1992)

Peralta, S. Estratigrafía y consideraciones paleoambientales de los depósitos marino- clásticos eopaleozoicos de la Precordillera Oriental de San Juan. XII Congreso Geológico Argentino y II Congreso de Exploración de Hidrocarburos, Actas 7, 128–137, Mendoza, Argentina (1993).

Frýda, J., Lehnert, O., Frýdová, B., Farkaš, J. & Kubajko, M. Carbon and sulfur cycling during the mid-Ludfordian anomaly and the linkage with the late Silurian Lau/Kozlowskii Bioevent. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 564, 110152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.110152 (2021).

Bassett, M. G. Facies in the Silurian plant-bearing succession of Angosto de Jarcas, southern Bolivia. 18º IAS Regional European meeting of sedimentology, Heidelberg. Gaia Heidelbergensis 3, 63 (1997).

Lehnert, O., Frýda, J., Joachimski, M., Meinhold, G. & Čáp, P. A latest Silurian Supergreenhouse: The trigger for the Pridoli Transgrediens Extinction Event. In Proceedings of the 34th International Geological Congress, Brisbane, Australia 5–10 (2012).

Scotese, C.R. Atlas of Silurian and Middle-Late Ordovician Paleogeographic maps (Mollweide Projections), Maps 73–80, 5, the early Paleozoic, PALEOMAP Atlas for ArcGIS; PALEOMAP Project: Evanston, IL, USA (2014).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) for the economic support. Additionally, we thank the Universidad Nacional de San Juan (UNSJ) and Instituto y Museo de Ciencias Naturales (IMCN) for providing the facilities to host the materials. Finally, the authors wish to thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their precise observations, whose significantly improved the original manuscript

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.D, O.A.C. and F.E.L designed the research project and conducted the fieldwork. J.M.D and E.P.C described all the specimens. C.M.A., F.A.P. and U.A. assisted in the fieldwork and preparation of the materials. J.A.A., C.K. and A.R.B revised the manuscript. All the authors wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Drovandi, J.M., Conde, O.A., Lopez, F.E. et al. The southwesternmost record of late Silurian (Pridolian) early land plants of Gondwana. Sci Rep 14, 22071 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63196-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63196-4