Abstract

In recent decades, the trend toward early same-day discharge (SDD) after surgery has dramatically increased. Efforts to develop adequate risk stratification tools to guide decision-making regarding SDD versus prolonged hospitalization after total hip arthroplasty (THA) remain largely incomplete. The purpose of this report is to identify the most frequent causes and risk factors associated with SDD failure in patients undergoing THA and total knee arthroplasty (TKA). A systematic search following PRISMA guidelines of four bibliographic databases was conducted for comparative studies between patients who were successfully discharged on the same day and those who failed. Outcomes of interests were causes and risk factors associated with same-day discharge failure. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated for dichotomous variables, whereas mean differences (MD) were calculated for continuous variables. Meta-analysis was performed using RevMan software. Random effects were used if there was evidence of heterogeneity. Eight studies with 3492 patients were included. The most common cause of SDD failure was orthostatic hypotension, followed by inadequate physical condition, nausea/vomiting, pain, and urinary retention. Female sex was a risk factor for failure (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63–0.93), especially in the THA subgroup. ASA score IV (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.14–0.76) and III (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.52–0.99) were risk factors, as were having > 2 allergies and smoking patients. General anesthesia increased failure risk (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.42–0.80), while spinal anesthesia was protective (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.17–2.24). The direct anterior and posterior approaches showed no significant differences. In conclusion, orthostatic hypotension was the primary cause of SDD failure. Risk factors identified for SDD failure in orthopedic surgery include female sex, ASA III and IV classifications, a higher number of allergies, smoking patients and the use of general anesthesia. These factors can be addressed to enhance SDD outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a common surgical procedure for the treatment of arthritis, with approximately 7 million Americans currently undergoing hip or knee replacement1. The demand for THA is expected to increase substantially in the coming decades owing to an aging population and rising obesity rates1. THA has traditionally been associated with a prolonged hospital stay of several days.

In recent decades, there has been a significant trend towards early same-day discharge (SDD) after THA surgery2. This shift towards SDD has been driven by various factors, including potential cost savings. For instance, one study estimated savings of approximately $4000 USD per patient using the SDD model compared to traditional post-THA hospitalization3.

The literature on THA failure highlights diverse causes, ranging from patient preference to inadequate postoperative motor function and pain control4,5. There is a significant variation in the early discharge criteria among institutions, and the definitions of SDD failure are heterogeneous. Consequently, there is uncertainty and lack of consensus regarding the precise risk factors associated with SDD failure after THA, as noted by Lieberman et al. in a recent study6. Despite its potential benefits, the practice of SDD after THA remains controversial and has been adopted unevenly across countries and healthcare systems. However, a systematic review reported SDD success rates after THA ranging from 91 to 95%, with significant benefits, such as lower infection risk, greater patient satisfaction, and cost savings3,7.

Efforts to develop adequate risk stratification tools to guide the decision-making process between SDD and prolonged hospitalization after THA have remained largely incomplete, as emphasized by Gazendam et al.8. Therefore, conducting a meta-analysis to better understand the risk factors associated with SDD failure is imperative for optimizing patient selection and improving clinical outcomes. The objective of this meta-analysis was to synthesize the available evidence and identify the most common causes of SDD failure after THA, and to examine the demographic, clinical, surgical, and anesthetic factors that contribute to a higher risk of SDD failure.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

This systematic review was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023471109) and conducted according to PRISMA guidelines9. A PICOS approach was utilized, where (P) the population included adult patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty, (I) the intervention group comprised patients who were successfully discharged on the same day, (C) the comparison group involved those who failed same-day discharge, and (O) the primary outcomes were causes and risk factors for failure of same-day discharge. Study designs eligible for inclusion were (S) comparative observational studies, such as prospective or retrospective cohort and case–control investigations. Compared same-day versus inpatient discharge rather than focusing on analysis of risk factors associated with ambulatory failure, as this outcome measure did not address the objective of evaluating modifiable risk profiles. Studies involving non-adult populations were excluded as the risk factors and considerations may differ for pediatric populations. Those with incomplete reporting of data were excluded due to the inability to extract pertinent information needed for meta-analysis. Studies using duplicate or overlapping samples were excluded to avoid including non-independent observations and violating statistical assumptions of meta-analysis. Those lacking comparable variables necessary to calculate standardized effect sizes across studies were excluded. Studies with a high risk of bias, were excluded to limit potential skewing of results from low quality evidence.

Information sources

The systematic search included the following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library, covering the period from August 1st to September 30th, 2023. Bibliographic references of included studies were also hand-searched to identify any additional pertinent reports not indexed in the databases. No limits were placed on publication date, study design or language.

Search methods for identification of studies

The search equation combined (“total hip arthroplasty” OR THA OR “total hip replacement” OR THR OR “total knee arthroplasty” OR TKA OR “total knee replacement” OR TKR) AND “Same-Day Discharge”. Two independent reviewers screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of potentially eligible studies according to the predefined selection criteria. Any discrepancies in study selection were resolved through discussion between the reviewers.

Data extraction and data items

Data were extracted from all included studies by two independent reviewers. In the event consensus could not be achieved, involvement of a third reviewer was planned to assess the disputed data items. Baseline study characteristics were collected: study period, region, study type, arthroplasty type (THA or THA/TKA), number of patients, number of females, age, and inclusion criteria. The primary variables were causes of failure and risk factors. The risk factors that could be compared in at least two studies were age, sex, race, BMI, ASA score, approach, previous TJA, general/spinal anesthesia, surgery start time, allergies, and smoking.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) criteria (Supplementary Table S1)10.

Assessment of results

Meta-analysis was performed using the Review Manager 5.4 software package provided by the Cochrane Collaboration. The mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for continuous variables, and the odds ratio (OR) for dichotomous variables. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi2 and I2 tests, with I2 values ranging from 0 to 100% considered low (25%), moderate (50%), and high (75%) heterogeneity. In the absence of statistical evidence of heterogeneity, a fixed-effects model was employed, whereas a random-effects model was used if significant heterogeneity was detected. To calculate the incidence of the most frequent causes, when the standard error (SE) was not reported, the incidence was calculated using the formula: SE = √I (1 − i)/n and 95% CI = I ± 1.96 × SE; where I = incidence11. Pooled incidences with 95% CI were calculated using random- and fixed-effects models. The Cochrane Handbook guidelines were followed to handle the missing data12.

Risk of bias across the studies

A funnel plot analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 software to assess potential publication bias graphically. The funnel plot displays each study's standard error on the y-axis against its effect estimate on the x-axis.

Additional analyses

Subgroup meta-analyses were performed based on arthroplasty type (THA vs TKA), given the review aimed to isolate the THA effect specifically. Subgroups were formed only when at least two studies reported on the outcome within that category.

Sensitivity analyses using Review Manager 5.4 software evaluated the reliability and potential influence of individual studies on outcomes. For each analysis, the single most influential or weighted study was removed based on sample size and the analysis was re-run.

The GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system was used13. The GRADE system was applied to each outcome included in our meta-analysis, considering factors such as study design, result consistency, estimation precision, potential biases, and clinical relevance of the findings. GRADEpro, an online platform specifically designed to facilitate implementation of the GRADE system, was used to generate evidence summaries and summary tables.

Results

Study selection

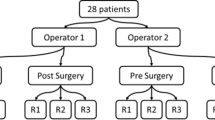

The initial literature search yielded 176 results, which were further refined by excluding review articles, case series, and case reports, leaving 53 articles. After reviewing titles and abstracts, duplicate studies, those that were not comparative, and those that did not report relevant outcome variables were excluded, leaving another 39 studies and 14. Upon examining the full text of these articles, a further 7 studies were excluded for not directly comparing success versus failure of same-day discharge, resulting in seven studies eligible for inclusion. The reference lists of the included studies were reviewed, and an two additional study that met the inclusion criteria was identified. In total, eight studies were finally included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1)4,5,6,8,14,15,16,17.

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the eight included studies. The included studies were published between 2018 and 2024. Eight studies, including 3492 patients, were included (2904 in the SDD success group and 588 in the SDD failure group). Eight studies were cohort studies (seven retrospective and one prospective). Six of the seven studies were conducted in the USA. A total of 1742 female patients were included (1432 in the SDD success group and 310 in the SDD failure group). Mean age ranged from 55.4 to 64.0 years in the SDD success group and from 56.5 to 64.0 years in the SDD failure group. The inclusion criteria for the individual studies are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Causes of same day discharge failure

The most frequent cause was orthostatic hypotension (Orthostatic hypotension 22.33%, 95% CI 12.66–32.00%; studies = 6), followed by inadequate physical condition (inadequate physical condition 18.17%, 95% CI 17.37–18.97%; studies = 6), nausea and vomiting (nausea and vomiting 11.20%, 95% CI 9.01–13.39%; studies = 5), pain (Pain 11.00%, 95% CI 5.39–16.61%; studies = 5), and urinary retention (Urinary retention 6.00%, 95% CI 1.92–10.08%; studies = 3).

Risk factors

Regarding risk factors, mean age was not found to be a risk factor (Fig. 2A). When age cutoffs were used, patients older than 65 years did not show a higher risk of failure (Fig. 2B), nor were differences observed in patients under 50 years of age (Fig. 2C). Female sex was associated with a higher risk of SDD failure (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63–0.93; participants = 3492; studies = 8; I2 = 26%). Subgroups showed that the THA group had significant differences (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.68–1.04; participants = 2945; studies = 5; I2 = 26%), whereas female sex was not a risk factor in the THA/TKA subgroup (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.65–1.02; participants = 2814; studies = 4; I2 = 29%). Race was also not shown to be a risk factor: black (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.32–1.09; participants = 1654; studies = 2; I2 = 0%), Asian (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.18–1.75; participants = 1654; studies = 2; I2 = 0%), and white (OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.95–2.26; participants = 1654; studies = 2; I2 = 0%). Mean BMI was also not a risk factor (MD − 0.03, 95% CI − 0.64 to 0.59; participants = 2689; studies = 6; I2 = 13%). When a cut-off BMI of 30 (obesity) was used, it also did not appear to be a risk factor (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.64–1.25; participants = 966; studies = 3; I2 = 0%).

Regarding ASA (Supplementary Table S3), ASA IV showed to be a risk factor for failure (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.14–0.76). ASA III was also a risk factor (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.52–0.99). However, when subgroups were analyzed, it was only a risk factor for THA (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.08–0.55) and not for THA/TKA (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.59–1.18). ASA II was also a risk factor (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.43–1.38). ASA I was a factor for SDD success (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.02–1.78). When the subgroups were analyzed, the THA subgroup did not show differences in ASA I (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.50–1.47), whereas the THA/TKA subgroup showed ASA I to be a success factor (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.13–2.18). A number of allergies greater than two were also shown to be risk factors for SDD failure (Fig. 3A). Patients who smoked were at a higher risk of SDD failure (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.35–0.94) (Fig. 3B). Previous TJA was a success factor (OR 2.83, 95% CI 1.42–5.64; participants, 798; studies, 2; I2 = 0%) (Fig. 3C). Earlier surgery time also influenced outcomes, with early time being a success factor (1.34, 95% CI 1.14–1.58; studies = 2) (Fig. 3D).

On the other hand, general anesthesia showed to be a risk factor for SDD failure (Fig. 4a), whereas spinal anesthesia showed to be a factor for SDD success (Fig. 4b). Finally, neither the direct anterior nor posterior approach showed significant differences between the success and failure groups (Fig. 4c,d) respectively.

Publication bias

Funnel plot analysis revealed symmetry with respect to all analyzed variables (Supplementary Fig. S1), indicating a relatively balanced representation of studies across different levels or categories of these factors and a lower likelihood of publication bias or selective reporting.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed by eliminating top-weight studies by comparing all outcomes. The direction of the results did not change except for the ASA I and general anesthesia variables, showing no significant differences: (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.69–1.44; participants = 2836; studies = 7; I2 = 0%) and (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.42–1.03; participants = 1076; studies = 4; I2 = 55%) respectively.

GRADE

The detailed GRADE assessment is shown in Table 2. There was low certainty evidence for the factors of age, sex, BMI, ASA III classification, and spinal anesthesia. However, the results related to general anesthesia and the type of surgical approach showed very low certainty. The studies primarily scored low quality owing to their retrospective design, and indirectness was mainly affected by small differences in demographic data.

Discussion

This meta-analysis aimed to identify the causes and risk factors for same-day discharge (SDD) failure after total hip arthroplasty (THA). The most common causes of SDD failure were orthostatic hypotension, inadequate physical condition, nausea and vomiting, pain, and urinary retention. Risk factors for SDD failure included female sex, higher ASA classifications (IV and III), having more than two allergies, smoking patients and general anesthesia. Previous joint replacement surgery, earlier surgery time, and spinal anesthesia were associated with successful SDD. Age, BMI, race, and surgical approach did not significantly impact the outcomes. The included studies in this meta-analysis were of high quality. However, it is important to note that the certainty of the results was low due to various factors, such as limitations in study design and inconsistencies among the included studies. Therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings.

These factors represent important areas for optimization through individualized perioperative strategies, as discussed in the literature. For example, Fraser et al. suggested limiting the excessive use of opioid narcotics to reduce postoperative nausea and dizziness, which are often exacerbated by medications such as pethidine or tramadol administered for pain control4. They proposed prioritizing non-opioid anesthetics and analgesics, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin or pregabalin, and local infiltration with long-acting local anesthetics4. Other recommended prophylactic measures include alpha-1-adrenergic agonists such as midodrine or ephedrine to increase blood pressure and counteract hypotension as well as a careful strategy of fluids guided by defined hemodynamic goals4.

When analyzing the causes of failure between total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total hip/knee arthroplasty (THA/TKA), the causes of failure were found to be similar and did not show significant differences, except in cases of inadequate physical condition. The inadequate physical condition was found to be significantly greater in THA patients than in THA/TKA patients. THA patients may have greater difficulty tolerating physical stress and load associated with surgery and subsequent rehabilitation.

Urinary retention is a common complication associated with the use of urinary catheters and has two important aspects. First, patient mobilization is affected by the presence of a catheter, which limits the patient’s ability to move. This can be particularly problematic in the post-surgical recovery process, where early mobility is crucial for prompt recovery. Additionally, in men with prostate issues, prolonged catheter use may require removal within two or three days. This can be challenging if the patient experiences urinary retention, as it is necessary to insert a new catheter to eliminate retained urine. In this scenario, the recovery process is further delayed, as the patient must wait for the patient to spontaneously urinate after catheter placement. Despite these considerations, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols advocate the avoidance of the routine use of urinary catheters. This is due to the associated risks, such as urinary tract infections, as well as the importance of early patient mobilization for successful recovery. To address this dilemma, strategies have been implemented to balance the need to prevent urinary retention and the risk of catheter use. These strategies include the preoperative assessment of urinary retention risk, optimal pain and fluid management, and selective and temporary catheterization in high-risk patients. Judicious use of local infiltrative anesthetics such as liposomal bupivacaine or ropivacaine could also benefit patients with urinary retention due to prostate hypertrophy or other causes, which is another main cause of SDD failure18. Local periarticular infiltration with long-acting drugs has been shown to significantly decrease pain and opioid use during the postoperative period after THA18. In addition to providing analgesia, local infiltration prevents systemic side effects of opioids and facilitates functional recovery. Adequate pain control promotes early mobilization and ambulation, which play key roles in achieving a safe same-day postoperative discharge. An inadequate physical condition or acute functional deterioration is the second most frequent cause of SDD failure4.

Other proposed strategies are accelerated or “fast-track” rehabilitation protocols, which emphasize early mobilization, preoperative optimization of comorbidities, comprehensive patient education, goal-directed fluid therapy, nausea/vomiting prophylaxis, and multimodal analgesia19. Other studies have proposed guidelines for selecting patients with SDD based on specific risk prediction scores. For example, based on the findings of this meta-analysis, Kim et al. instituted a rigorous policy of goal-directed intravenous fluid hydration during the perioperative period14. They also incorporated the prophylactic use of antiemetics such as scopolamine in patients with a history of postoperative nausea/vomiting after prior anesthesia, achieving an SDD success rate of 95% through this proactive approach to prevent the two main causes of failure14.

These findings could be related to the fact that general anesthesia is associated with a higher risk of SDD failure than neuroaxial or regional anesthesia. While spinal anesthesia may be linked to prolonged recovery from transient motor or sensory impairments, regional blockade promotes earlier rehabilitation by avoiding systemic polypharmacy. The risk of accidentally infiltrating long-acting local anesthetics such as liposomal bupivacaine near the sciatic nerve during the arthroplasty procedure, which can lead to up to three days of transient neurological dysfunction, must also be considered19. However, in general, regional anesthesia via lower-extremity nerve blocks allows for faster functional recovery and shorter hospital stay than general anesthesia and intravenous opioid use19.

Other identified risk factors included ASA physical status ≥ II, later surgery start time, and history of multiple drug allergies20,21. ASA class II or higher is inherently associated with more severe comorbidities, making it difficult to meet the strict criteria for early discharge. Similarly, overweight or obesity with an elevated body mass index did not show an independent association with SDD failure, despite possibly expecting otherwise due to difficulties with early mobilization in these patients.

A later surgery start time likely reflects limited operating room and auxiliary staff availability beyond certain hours, as discussed by Gazendam et al.8. Ideally, arthroplasties should be scheduled during times that allow for adequately supervised recovery and rehabilitation, considering the institutional resources. Patients with multiple-drug allergies have worse functional outcomes and higher SDD failure, possibly because of the limited pharmacological options for optimal pain and nausea control in the perioperative period20,21.

Protective factors included ASA of Anesthesiologists class I physical status, history of previous joint arthroplasties, and use of neuroaxial versus general anesthesia6. Patients with ASA class I enjoyed better overall health without significant comorbidities, thus meeting the criteria for early discharge. Individuals with previous joint surgeries may have more realistic expectations of expected recovery and may be better prepared to undergo the perioperative process both physically and psychologically.

Regarding intrinsic demographic characteristics, a higher risk of SDD failure was observed in women than that in men. This could be related to multifactorial differences in preoperative expectations, pain thresholds, and psychosocial factors between sexes22. Women are known to have worse functional outcomes after adjusting for other factors before arthroplasty and worse patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) after surgery22,23. Effective patient communication and structured educational protocols are essential, given that patient expectations are a significant predictor of outcomes in total hip and knee arthroplasty24. A recent randomized controlled trial demonstrated that the use of a mobile application improved the quality of life, function, and pain compared to standard education in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty25.

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that among the included studies, neither a direct anterior nor a posterior surgical approach yielded a statistically significant difference in the rates of successful versus failed same-day discharge following total joint arthroplasty. Although direct anterior approaches may offer better functional outcomes and quicker recovery26, the data found no differentiation in terms of same-day discharge rates. A possible explanation could be that multiple joint- and patient-specific factors, beyond the surgical approach, play a greater role in determining the feasibility of same-day discharge. For instance, comorbidities, frailty, socioeconomic support at home, and surgical team protocols/resources may influence the discharge timing more than the approach alone. Additionally, the two included studies with 805 combined patients were underpowered to detect small differences in the effect size.

The presence of a caregiver may also influence outcomes as married patients generally receive more support than single, divorced, or widowed individuals. Singh et al. discussed the importance of having a committed caregiver available at discharge to ensure a safe transition home, specifically in the context of enhanced recovery programs16. Although not analyzed in this meta-analysis, psychological parameters such as anxiety, depression, and satisfaction strongly impact recovery and adaptation after arthroplasty27. Therefore, perioperative psychosocial evaluation and adequate psychological support may optimize SDD outcomes. Dissatisfaction after discharge has been linked to greater opioid use and poorer function28.

While costs were not directly compared in this meta-analysis, previous evidence suggests that the SDD model is associated with significant reductions in hospital costs compared with prolonged stays. A study in China reported a significant decrease in total costs following total hip arthroplasty with SDD, saving an average of approximately 10,900 yuan per patient29.

All the factors studied in this meta-analysis could be considered and influenced the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol, which is a comprehensive approach designed to optimize the care of surgical patients by implementing evidence-based strategies before, during, and after surgery30. It has been observed that only some components of the ERAS program are widely implemented in current clinical practice30. This approach aims to minimize surgical stress, maintain physiological function, and accelerate recovery to improve outcomes and reduce hospital stay30. ERAS protocols in joint replacement surgery have been associated with a reduced length of hospital stay, decreased pain, cost savings, improved patient-reported outcomes, and decreased incidence of complications, although the quality of evidence remains low30. Some of the recommendations of this protocol include preoperative education, optimization of certain factors (smoking, alcohol, anemia), preoperative fasting, standard anesthesia protocols, use of local anesthetics for pain control, prevention of nausea and vomiting, management of perioperative blood loss with tranexamic acid, oral analgesia, maintenance of normothermia, antimicrobial and antithrombotic prophylaxis, perioperative surgical factors, fluid management, postoperative nutritional care, and early mobilization31.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. First, most studies included in this review were retrospective in nature, which can introduce selection bias and limit the data quality. Additionally, owing to the lack of standardization in data collection, there were variables of interest that could not be compared across studies because of the unavailability of that information in published reports. There is a lack of analysis on the role of psychological aspects or possible psychiatric alterations in same-day discharge failure. These factors can significantly influence the outcome, but were not addressed in the studies included in this meta-analysis, which may limit our complete understanding of the determinants of same-day discharge failure after arthroplasty. Furthermore, the low number of articles available for certain variables limited our ability to perform subgroup analyses and to explore potential interactions between variables of interest. This may affect the generalizability of the results and identification of specific risk factors in the determined subpopulations. Another limitation was the inclusion of the results of total hip and knee arthroplasty without proper separation. Although subgroup analyses were performed when possible to control for the heterogeneity between studies, this mixing of results can affect the interpretation and applicability of the findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides valuable information on the causes of failure and risk factors for same-day discharge after arthroplasty. These results highlight the importance of addressing specific identified complications, such as orthostatic hypotension, inadequate physical condition, and nausea/vomiting, to improve the same-day discharge outcomes. Additionally, the female sex, smoking patients, physical status of the ASA of Anesthesiologists, and type of anesthesia were identified as important clinical considerations. The type of approach did not influence the results. These findings underscore the need to implement perioperative management strategies targeted at preventing and adequately addressing identified complications to improve the feasibility and outcomes of same-day discharge after arthroplasty. Additionally, studies that allow for proper separation of the results between total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are recommended.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Kremers, M. et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 97, 1386e97. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.N.01141 (2015).

Kelly, M. P., Calkins, T. E., Culvern, C., Kogan, M. & Della Valle, C. J. Inpatient versus outpatient hip and knee arthroplasty: Which has higher patient satisfaction?. J. Arthroplasty 33, 3402–3406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.07.025 (2018).

Bertin, K. C. Minimally invasive outpatient total hip arthroplasty: A financial analysis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 435, 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000157173.22995 (2005).

Fraser, J. F., Danoff, J. R., Manrique, J., Reynolds, M. J. & Hozack, W. J. Identifying reasons for failed same-day discharge following primary total hip arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 33, 3624–3628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.003 (2018).

Keulen, M. H. F. et al. Reasons for unsuccessful same-day discharge following outpatient hip and knee arthroplasty: 5½ years’ experience from a single institution. J. Arthroplasty 35, 2327-2334.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.064 (2020).

Lieberman, E. G., Hansen, E. J., Clohisy, J. C., Nunley, R. M. & Lawrie, C. M. Allergies, preoperative narcotic use, and increased age predict failed same-day discharge after joint replacement. J. Arthroplasty 36(7S), S168–S172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.01.015 (2021).

Hoffmann, J. D. et al. The shift to same-day outpatient joint arthroplasty: A systematic review. J. Arthroplasty 33, 1265–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.11.027 (2018).

Gazendam, A. M. et al. Causes and predictors of failed same-day home discharge following primary hip and knee total joint arthroplasty: A Canadian perspective. Hip Int. 33, 576–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/11207000221111101 (2023).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Slim, K. et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 73, 712–716 (2003).

Allagh, K. P. et al. Birth prevalence of neural tube defects and orofacial clefts in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 5, 9039 (2015).

Higgins, J. P. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Wiley, 2019).

Guyatt, G. H. et al. GRADE guidelines: 13. Preparing summary of findings tables and evidence profiles-continuous outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 66, 173–183 (2013).

Kim, K. Y. et al. Primary total hip arthroplasty with same-day discharge: Who failed and why. Orthopedics 41, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20171127-01 (2018).

Rodriguez, S. et al. Ambulatory total hip arthroplasty: Causes for failure to launch and associated risk factors. Bone Jt. Open 3, 684–691. https://doi.org/10.1302/2633-1462.39.BJO-2022-0106.R1 (2022).

Singh, V., Nduaguba, A. M., Macaulay, W., Schwarzkopf, R. & Davidovitch, R. I. Failure to meet same-day discharge is not a predictor of adverse outcomes. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 142, 861–869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-021-03983-0 (2022).

Foley, D. P., Ghosh, P., Ziemba-Davis, M., Sonn, K. A. & Meneghini, R. M. Predictors of failure to achieve planned same-day discharge after primary total joint arthroplasty: A multivariable analysis of perioperative risk factors. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 32, e219–e230 (2024).

Bronson, W. H., Doran, J. P., Slover, J., Perretta, D. & Iorio, R. Unanticipated transient sciatic nerve deficits from intra-wound liposomal bupivacaine injection during total hip arthroplasty. Arthroplast. Today 1, 21–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2015.05.001 (2015).

Harsten, A., Kehlet, H., Ljung, P. & Toksvig-Larsen, S. Total intravenous general anaesthesia vs. spinal anaesthesia for total hip arthroplasty: A randomised, controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 59, 298–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12456 (2015).

Keulen, M. H. F. et al. Predictors of (un)successful same-day discharge in selected patients following outpatient hip and knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 35, 1986–1992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.03.034 (2020).

Nam, D., Li, K., Riegler, V. & Barrack, R. L. Patient-reported metal allergy: A risk factor for poor outcomes after total joint arthroplasty?. J. Arthroplasty 31, 1910–1915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.016 (2016).

Katz, J. N. et al. Differences between men and women undergoing major orthopedic surgery for degenerative arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 37, 687–694. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780370512 (1994).

Lall, A. C. et al. Effect of marital status on patient-reported outcomes following total hip arthroplasty: A matched analysis with minimum 2-year follow-up. Hip Int. 31, 362–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120700019864015 (2021).

Halawi, M. J. et al. Patient expectation is the most important predictor of discharge destination after primary total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 30, 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2014.10.031 (2015).

Timmers, T. et al. The effect of an app for day-to-day postoperative care education on patients with total knee replacement: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7, e15323. https://doi.org/10.2196/15323 (2019).

Ang, J. J. M., Onggo, J. R., Stokes, C. M. & Ambikaipalan, A. Comparing direct anterior approach versus posterior approach or lateral approach in total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 33, 2773–2792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-023-03528-8 (2023).

Ali, A., Lindstrand, A., Sundberg, M. & Flivik, G. Preoperative anxiety and depression correlate with dissatisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 186 patients, with 4-year follow-up. J. Arthroplasty 32, 767–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.033 (2017).

Lopez-Olivo, M. A. et al. Psychosocial determinants of outcomes in knee replacement. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 1775–1781. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.146423 (2011).

Shi, Y. et al. Cost-effectiveness of same-day discharge surgery for primary total hip arthroplasty: A pragmatic randomized controlled study. Front. Public Health 25, 825727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.825727 (2022).

Changjun, C. et al. Enhanced recovery after total joint arthroplasty (TJA): A contemporary systematic review of clinical outcomes and usage of key elements. Orthop. Surg. 15, 1228–1240 (2023).

Changjun, C., Xin, Z., Yue, L., Liyile, C. & Pengde, K. Key elements of enhanced recovery after total joint arthroplasty: A reanalysis of the enhanced recovery after surgery guidelines. Orthop. Surg. 15, 671–678 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved of the submission of this manuscript. Study concept and design, J.M.L.-E, G.M., J.G.-A., M.B. and M.S.-J.; acquisition of data, J.M.L.-E, G.M., J.G.-A., M.B. and M.S.-J; analysis and interpretation of data, J.M.L.-E, G.M., J.G.-A., M.B. and M.S.-J; Statistical expertise: J.M.L-E., G.M.; preparation of manuscript, J.M.L.-E, G.M., J.G.-A., M.B. and M.S.-J; and final approval of the manuscript, J.M.L.-E, G.M., J.G.-A., M.B. and M.S.-J.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamo-Espinosa, J.M., Mariscal, G., Gómez-Álvarez, J. et al. Causes and risk factors for same-day discharge failure after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 14, 12627 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63353-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63353-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Retrospective comparison of chloroprocaine and mepivacaine in spinal anesthesia for same-day discharge TKA

Knee Surgery & Related Research (2025)

-

Efficacy and safety of pregabalin for postoperative pain after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2025)