Abstract

The use of unmanned operations to monitor mining induced land subsidence is increasing. This study conducts a detailed comparative analysis of accuracy of measured ground deformation provided by Differential Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (D-InSAR), Small Baseline Subset (SBAS), and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) tilt photogrammetry with respect to levelling measurements. Based on such analysis we propose an integrated approach that combines multiple remote sensing methods to achieve a better global accuracy in the land subsidence monitoring in mining areas. Conducted at the Banji Coal Mine, this study collected subsidence data from April 10, 2021, to June 28, 2022, through D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV techniques. After segmenting the subsidence basin into distinct zones, we qualitatively assessed each area with UAV-derived 3D models and quantitatively evaluated the precision of all applied techniques, benchmarking against leveling data. Our findings indicate that integrating D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV technologies significantly enhances monitoring accuracy over any single method, demonstrating their combined effectiveness in different subsidence areas. Consequently, the synergistic integration of D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV technologies, capitalizing on their complementary strengths, enables the achievement of intuitive, comprehensive, and high-precision monitoring of subsidence basins in mining areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global industrialization escalates, the phenomenon of land subsidence resulting from the extraction of subterranean resources presents a formidable global challenge. This occurrence poses substantial risks to the safety and assets of individuals residing in mining regions and represents a significant threat to the equilibrium of global ecosystems. Notably, coal extraction, a principal energy source for humanity, is especially associated with land subsidence issues1. Consequently, the effective monitoring and prevention of surface subsidence in these areas are of paramount urgency.

In the context of surface subsidence monitoring within mining regions, the current standard practices predominantly involve the use of the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and traditional leveling techniques. These methodologies, while established, exhibit several drawbacks such as limited spatial resolution and confined monitoring scope. Additionally, they demand substantial time and labor resources, which constrains their efficiency and applicability in extensive, dynamic mining environments2,3,4. There is a recognized global imperative for the swift and precise tracking of surface deformations in mining areas5. Consequently, there is a need for a comparative analysis of the capabilities of various remote sensing technologies in monitoring surface subsidence in mining areas.

D-InSAR and SBAS, as emergent active remote sensing technologies, have gained widespread application in mining subsidence monitoring recently6. D-InSAR, in contrast to traditional methods, offers extensive monitoring coverage and cost-effectiveness while providing continuous spatial deformation data7,8. Its theoretical deformation accuracy can reach centimeter to millimeter levels. Hou et al.9 employed an enhanced probabilistic integral model with D-InSAR to effectively forecast and refine mining subsidence monitoring accuracy. Additionally, Wang et al.10 leveraged the Boltzmann function-assisted D-InSAR technique for precise surface deformation predictions in mining areas, significantly mitigating geological hazards. Their findings contribute vital insights to construction safety in these areas. Despite its merits, D-InSAR’s capacity to detect large gradient deformations is limited, and it is susceptible to various noises and atmospheric delays, posing challenges to its broader adoption in subsidence monitoring. The SBAS technique, employing multiple images and a small baseline strategy, effectively mitigates errors and noise attributable to temporal and spatial baselines, atmospheric influences, and surface scattering property variations11,12,13. This technique is adept at monitoring gradual and sustained deformation processes. Liu et al.14 utilized a combination of SBAS and Geographic Information System (GIS) technologies to assess the surface subsidence of a mine in Yangquan, elucidating both the intensity of subsidence in crucial areas and the associated potential damage risks. Similarly, Zhai et al.15 employed SBAS to track ground subsidence at Yuncheng coal mine, notably enhancing result precision and dependability by integrating corrections based on leveling data. Nonetheless, the SBAS method faces limitations in rapidly deforming regions or in areas with significant gradient changes, and its efficacy is reduced in zones characterized by dense vegetation or low coherence.

As an emerging technology in the realm of passive remote sensing, UAV inclined photogrammetry has recently gained widespread application in disaster monitoring and three-dimensional modeling. The use of UAV tilt photogrammetry presents distinct advantages compared to nadir UAV photogrammetry, particularly by offering enhanced three-dimensional visual information. This enhancement significantly improves the accuracy of 3D reconstruction for terrain and structures, particularly in complex terrains or urban environments. Notably, UAVs offer mobility, flexibility, and cost-effectiveness16,17,18. The data they produce is not only intuitive but also rich in detail, particularly when compared to InSAR technology. The enhanced precision of UAV photogrammetry, which provides pixel resolution as fine as a few centimeters, markedly exceeds the capabilities of satellite imagery, which generally offers resolutions on the order of several meters. This superiority enables the acquisition of more detailed and accurate data, crucial for applications necessitating fine-scale analysis. UAV tilt photogrammetry can achieve surface deformation monitoring accuracy to the decimeter or even centimeter level, rendering it highly suitable for monitoring significant gradient deformations in mining areas. Zhou et al.19 successfully employed UAVs to monitor surface subsidence at the Wangjiata coal mine, proving the technology’s efficacy in quickly gathering detailed surface subsidence basin data and accurately inverting mining subsidence prediction parameters. However, the scope of UAVs in deformation monitoring is somewhat constrained, particularly in detecting minor deformations at the edges of mining subsidence basins19.

The use of a single remote sensing technique for monitoring surface subsidence in mines encounters numerous challenges. Recent advances by researchers have demonstrated significant progress through the integration of multiple remote sensing methods applied to the monitoring and prediction of mining subsidence. For instance, Chen et al.20 conducted a thorough evaluation and calibration focusing on D-InSAR and SBAS for subsidence monitoring in mining areas. They assessed the effectiveness of these techniques across areas with varying subsidence magnitudes and introduced a methodology to enhance InSAR monitoring outcomes using leveling data. Similarly, Pawluszek–Filipiak et al.21 innovatively crafted a kriging-based integration approach for monitoring subsidence in mining areas, which synergistically utilizes D-InSAR and SBAS technologies. The method’s effectiveness and precision were rigorously tested and confirmed through empirical studies. Wang et al.22 effectively monitored surface subsidence in a plateau alpine open-pit mine by integrating UAV and Persistent Scatterets (PS) techniques. In their study of the Datong Coal Field, Xu et al.23 employed D-InSAR, Stacking-InSAR, and SBAS methods, finding that Stacking-InSAR exhibited high efficiency and accuracy in dense mountainous regions. Zhang et al.24 employed a synthesis of D-InSAR and UAV methodologies to enhance the precision of surface subsidence monitoring in mining regions. Their findings indicate that this composite technique offers greater accuracy than the use of either D-InSAR or UAV in isolation. Furthermore, Wang et al.25 developed a highly precise surface deformation monitoring model by amalgamating UAV, D-InSAR, and SBAS data with a probabilistic integral model, accurately capturing the dynamic surface subsidence in the mining area. Lastly, Zhu et al.26 applied a synergistic monitoring approach using D-InSAR and UAV, inverting the expected surface subsidence parameters via the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) algorithm. Their results closely aligned with the actual ground deformation patterns, validating the method’s effectiveness.

Current research on monitoring surface deformation in mining areas utilizing novel remote sensing technologies typically focuses on one or two methods to monitor or assess mining subsidence patterns and invert the expected subsidence parameters. Yet, there is often a lack of comprehensive quantitative assessment regarding the surveillance effectiveness of UAV, D-InSAR, and SBAS technologies across diverse areas of land subsidence. By considering level measurement data as the benchmark, this research compares and analyzes the capabilities of D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV techniques in monitoring mining surface subsidence. Subsequently, this research proposes an integrated method that combines D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV techniques. This integration aims to achieve an intuitive, comprehensive, and high-precision monitoring of the subsidence basin in mining areas.

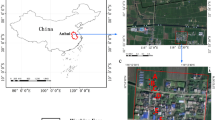

Study area and data

For the purposes of this research, the Banji Coal Mine, located in Bozhou City, Anhui Province, was chosen as the primary field of study. This mine is operated by China Coal Xinji Energy Company Limited and is administratively located within Huji Town, Lixin County. The 110,801 working face of this mine has a strike length of 1,237 m and an inclination width of 280 m, with the coal seam having an average depth of 767 m. For the monitoring of the 110,801 working face, 98 points were established along the strike and 92 observation points along the inclination. Figure 1 in the paper provides a visual representation of the study area’s geographic location.

Overview of the research area: (a) Shows the geographic location of the research area. (b) The red rectangle indicates the 110,801 working face, black dots represent monitoring points, black pentagram A indicates the central subsidence area, black pentagram B indicates the moderate subsidence area, and black pentagram C indicates the edge subsidence area.

In this study, the radar data employed for D-InSAR and SBAS analyses were acquired from European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel-1A satellite, cover the period from the 10th of April in 2021 to the 28th of June in 2022, encompassing a total of 38 images. The pertinent parameters are detailed in Table 1. Additionally, the external Digital Elevation Model (DEM) utilized is derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), presenting a spatial resolution characterized by a 30-m grid. In this study, UAV oblique photogrammetry was conducted using a DJI Matrice 300 RTK UAV, which was equipped with a five-lens V2 tilt camera. The data collection occurred on two separate dates: April 10, 2021, and June 28, 2022. The associated parameters are presented in Table 2. Conducted between April 10, 2021, and June 28, 2022, the leveling measurements complied with the criteria for Class III leveling precision. This protocol was meticulously followed to ensure that the elevation error in each measurement was confined to a maximum of 3.5 mm. These precise surveys formed the foundation for corroborating the accuracy of the results obtained from D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV monitoring techniques.

Methods

Measurement of subsidence at monitoring points using D-InSAR

D-InSAR operates on the principle of analyzing phase differences within interferometric images27, as encapsulated by the following equation:

In this context, \(\varphi\) represents the interferogram phase information acquired via D-InSAR. The deformation phase is denoted by \({\varphi }_{d}\), the flat phase by \({\varphi }_{f}\), the terrain phase by \({\varphi }_{t}\), the atmospheric phase by \({\varphi }_{a}\), and the noise phase by \({\varphi }_{n}\). Precision orbit data and external DEM data are employed to eliminate the flat and terrain phases, respectively. Similarly, a filtering method is applied to attenuate the atmospheric and noise phases, thereby enhancing the extraction of deformation phase information that is indicative of ground deformation. However, due to the periodic nature of trigonometric functions, the differential interferometric phase is confined within the range of \(\left[ { - \;\pi ,\;\pi } \right]\). Therefore, it is imperative to unravel the phase to obtain the differential interferometric phase \({\varphi }_{r}\), which accurately represents the actual ground surface deformation28,29. The deformation along the radar line of sight can then be quantified using the following equation:

D represents the surface deformation along the radar line-of-sight, \(\lambda\) is the radar wavelength, and \({\varphi }_{r}\) is the differential interferometric phase corresponding to the actual surface deformation. After obtaining the deformation along the radar line-of-sight (LOS) with D-InSAR, we convert these measurements into vertical deformation to determine the subsidence monitoring results.

In this study, the data processing phase employed SARscape software, specifically version 5.6.2, which is a product developed by SARmap, an esteemed organization situated in Caslano, Switzerland. The software was operated within the framework of the ENVI platform, a widely recognized tool in the field of remote sensing analysis. To minimize the relative temporal baseline for interferometry and ensure optimal interference effects for each pair, 35 image pairs were constructed using SAR images from April 10, 2021, to June 28, 2022. The temporal baseline for all interferometric pairs was 12 days, except for two pairs covering April 10, 2021, to May 4, 2021, and May 4, 2021, to May 28, 2021, which had a baseline of 24 days. Settlement data were extracted for each time period at the monitoring points. These data were then cumulatively summed to calculate the total subsidence at each monitoring point from April 10, 2021, to June 28, 2022. Figure 2 presents the cumulative subsidence results of the mining area, as monitored by D-InSAR.

Measurement of subsidence at monitoring points using SBAS

SBAS involves acquiring N images of the same region. These images undergo preprocessing steps such as alignment, cropping, and multiviewing to create a short baseline dataset. This dataset formation ensures high coherence in the interferometric pairs, effectively addressing the incoherence issues arising from spatial and temporal baselines. Each interferometric pair is then processed through differential interferometry, filtering, and de-entanglement to accurately derive the de-entangled phase. Atmospheric errors are mitigated using spatial and temporal filtering, enabling the accurate determination of the cumulative deformation time series relative to the first SAR image30,31,32. Ultimately, the surface Line-of-Sight (LOS) deformation detected via SBAS is transformed into vertical deformation to derive the final subsidence monitoring outcomes.

In this study, SBAS data were processed using SARscape software (version 5.6.2). The maximum temporal and spatial baselines were set at 50 days and 2%, respectively. A total of 38 SAR images from April 10, 2021, to June 28, 2022, were combined based on these thresholds to form 131 temporal differential interferometric pairs. These pairs were then processed to acquire deformation information for the study area. Due to incoherence resulting from large gradient deformation, SBAS failed to extract a sufficient number of high-coherence pixels in the central area of the subsidence basin. Consequently, it was not possible to obtain subsidence data for all monitoring points. To address this, the study employed the kriging method to interpolate SBAS results, thereby deriving subsidence data for all monitoring points, as depicted in Fig. 3.

Measurement of subsidence at monitoring points using UAV

The essence of UAV oblique photography involves constructing high-precision route or area network models using a succession of overlapping aerial images, coupled with photogrammetric techniques and a limited number of ground image control points33. Central to this process is aerial triangulation, which hinges on the precise data from positioning systems and ground control points for the meticulous orientation correction of aerial images34. The fundamental principle of aerial triangulation rests on the geometric postulate that the photograph’s projection center, specific image points, and corresponding ground control points must align collinearly. In this methodology, each image is analyzed as an independent unit. Integration of homonymous points and ground control points across images establishes a connected regional network. Subsequently, the coordinates of densified points are precisely determined through global adjustments to this network. The core of this procedure is the covariance equation for the center projection, facilitating the construction of two corresponding error equations based on each photograph’s image point coordinates. Additionally, the six parameters required for the external orientation elements of the image are deduced via a least-squares leveling method. This series of meticulous calculations and adjustments enables the accurate determination of each densified point’s coordinates, achieving high-precision geographic mapping35,36.

The UAV imagery is processed to generate a point cloud dataset, encapsulating extensive 3D coordinate information of the ground surface. This data effectively delineates the ground’s shape and features, facilitating the construction of a Digital Surface Model (DSM) for the study area37. Subsequently, a process of real-world 3D modeling is undertaken. Here, the point cloud data are transformed into an irregular triangular mesh structure. This phase includes model optimization strategies, such as mesh simplification to enhance processing efficiency, and texture mapping. The latter involves transferring texture information from the original imagery onto the 3D model, thereby augmenting its visual realism and detail. The model undergoes rigorous validation and adjustment, culminating in the creation of a highly accurate and intricately detailed 3D model.

In this study, Bentley’s ContextCapture software (version 4.4.10) was employed for UAV data processing, resulting in the creation of DSMs and 3D models for two specific dates: April 10, 2021, and June 28, 2022. The determination of subsidence levels at specified monitoring locations during a defined temporal interval necessitated the retrieval of elevation data from the DSMs corresponding to the respective dates under consideration. These extracted elevation values were subsequently subjected to a subtraction operation, resulting in the computation of the overall subsidence magnitude occurring at these designated monitoring sites over the specified time frame, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

DSMs generated by UAV at two time points. (a) DSM generated by a UAV on April 10, 2021; (b) DSM generated by a UAV on June 28, 2022. After generating the DSMs, the elevation values of the monitoring points at the two time points are extracted and subtracted to determine the final subsidence amount at each monitoring point.

Division of regions in the subsidence basin

To accurately analyze the monitoring accuracy of D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV technologies, this study combines the principles of InSAR and UAV technologies with the patterns of surface movement and deformation in mining subsidence areas. Accordingly, the subsidence basin is divided into three zones: the central subsidence area, the moderate subsidence area, and the peripheral subsidence area. In mining subsidence research, the main influence radius is a critical concept. This study defines the outer boundary of the central subsidence area as the locations where the subsidence value reaches 0.16 \({W}_{0}\), with \({W}_{0}\) denoting the maximum subsidence. At these points, the surface exhibits maximal positive curvature. The experiment revealed that the maximum subsidence recorded at the monitoring points, determined through leveling measurements, was 2.52 m. Consequently, areas experiencing subsidence exceeding 0.4 m have been designated as the central subsidence area.

Zebker et al.38 observed that accurate deformation solutions become unfeasible when the deformation between neighboring interferometric image elements exceeds half the wavelength. Given that the wavelength of Sentinel 1A is 0.056 m, the maximal resolvable deformation for adjacent image elements theoretically stands at 0.028 m. By mining subsidence science standards, points with a subsidence of 0.01 m are identified as the subsidence boundary. SBAS, known for its higher theoretical accuracy than D-InSAR in detecting minor deformations at subsidence boundaries, employs multiple images and a small baseline strategy to mitigate errors and noise stemming from temporal and spatial baselines, atmospheric effects, and surface scattering characteristic variations. Consequently, in this study, regions are classified based on subsidence levels: those with subsidence below 0.028 m are identified as the edge subsidence zone; areas experiencing subsidence between 0.028 and 0.4 m are categorized as the moderate subsidence zone; and regions where subsidence exceeds 0.4 m are defined as the central subsidence zone.

The methodology of this study is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Results

Qualitative analysis of surface subsidence based on real-scene 3D models

The three-dimensional model of the mining zone, generated through UAV inclined photogrammetry, provides a unified spatio-temporal framework for deformation monitoring. Figure 6 presents the actual three-dimensional model of the mining area as of June 28, 2022, and illustrates the distribution of the central, moderate, and edge subsidence zones, offering a visual overview of the overall subsidence of the terrain in the mining area.

Figure 7a,b illustrate the central subsidence area, where surface deformation reached approximately 2 m between April 10, 2021, and June 28, 2022. Significant changes in land cover were observed in this area. The majority of village houses suffered damage, leading to demolition. Consequently, the land cover transformed from buildings and agricultural fields to wasteland. Additionally, the extent and depth of waterlogged areas in the central part of the subsidence basin have markedly increased. Our research demonstrates the application of UAV-acquired point cloud data to overcome the challenges posed by InSAR decorrelation in areas with significant surface deformation gradients and varied surface cover. The processed UAV data provided high-resolution three-dimensional models and Digital Surface Models (DSMs), facilitating precise deformation analysis in the region of study.

3D models: (a) 3D model of the central subsidence area on April 10, 2021; (b) 3D model of the central subsidence area on June 28, 2022; (c) 3D model of the edge subsidence area on April 10, 2021; (d) 3D model of the edge subsidence area on June 28, 2022; (e) 3D model of the moderate subsidence area on April 10, 2021; (f) 3D model of the moderate subsidence area on June 28, 2022.

The subsidence edge area, depicted in Fig. 7c,d, exhibits surface deformation of approximately 10 mm. In this periphery of the subsidence basin, due to minimal subsidence, the village structures remain largely unchanged, and the surface cover type is relatively stable. This stability allows for the extraction of high-coherence image elements, rendering the area suitable for D-InSAR and SBAS monitoring. Figure 7c,d shows a notable density of trees and houses in the area. To accurately determine the overall surface elevation of this region, it is essential to apply a filtering algorithm to the DSM that effectively removes the impact of the heights of both vegetation and buildings. In mining subsidence research, a 10 mm subsidence point is considered a boundary indicator of the surface subsidence basin. While the accuracy of UAV monitoring can achieve sub-centimeter precision, it lacks the capability to discern a 10 mm subsidence boundary. In contrast, InSAR’s sensitivity to minor deformations gives it a significant edge over UAV in monitoring the marginal subsidence areas.

Figure 7e,f illustrate the moderate subsidence area, where surface deformation measures approximately 0.4 m. Notably, the vegetation type on the surface undergoes significant changes during the subsidence period. In processing D-InSAR and SBAS data, this area’s coherence coefficient is lower compared to the edge subsidence area, resulting in relatively poorer deformation monitoring accuracy. Therefore, a quantitative analysis of the monitoring effectiveness of D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV technologies in this moderate subsidence area is imperative, particularly in conjunction with the collected leveling data.

Quantitative comparison of multi-source monitoring data in different subsidence areas

This study employed SBAS, D-InSAR, and UAV technologies to obtain the subsidence measurements at monitoring points from April 10, 2021, to June 28, 2022. Focusing on three areas within the subsidence basin, this research evaluated the monitoring effectiveness of each method in different subsidence regions by comparing them against leveling data, considered as the ground truth. The evaluation was based on three metrics: maximum absolute error, mean absolute error, and root mean square error. Tables 3 and 4 present the monitoring results of the dip line and strike line in each subsidence area, respectively. Figure 8 depicts the absolute error values in the monitoring results obtained from UAV, D-InSAR, SBAS, and their integrated data, using leveling survey results as the benchmark for ground truth.

Comparison of absolute errors for multi-source monitoring data: (a) dip line and (b) strike line. The image illustrates the absolute errors in subsidence monitoring results obtained from UAV, D-InSAR, SBAS, and the integrated outcomes. The horizontal axis shows the identification numbers of the monitoring points, while the vertical axis represents the absolute errors.

The results of the study reveal that in the central subsidence zone, the error associated with subsidence measurements obtained through UAV technology is significantly low. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for UAV technology is observed to be in excess of 94% lower compared to D-InSAR, and surpasses 96% lower than that observed for SBAS. Conversely, within peripheral subsidence regions, SBAS technology demonstrates the least measurement error in subsidence detection, where its RMSE exceeds 25% lower than that of D-InSAR, and is over 83% lower compared to UAV technology. In areas experiencing moderate subsidence, the measurement error recorded for D-InSAR is the minimal, with its RMSE being substantially over 76% lower than that of UAVs and more than 63% lower than SBAS.

Comparative analysis of the accuracy of integrated monitoring methods

This research introduces an innovative surface subsidence monitoring methodology for mining areas, integrating D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV technologies. Specifically, the method allocates UAV monitoring to the central subsidence zone, D-InSAR to areas of moderate subsidence, and SBAS to the peripheral zones. This comprehensive approach ensures accurate subsidence measurement across all monitored points. Figure 9 presents a comparative analysis of subsidence measurements at various monitoring points within the mining area, spanning from April 10, 2021, to June 28, 2022. These measurements were obtained using four distinct monitoring methodologies, alongside an integrated approach.

Comprehensive comparison of multi-source monitoring data: (a) dip line and (b) strike line. The image depicts the subsidence of monitoring points as measured by levelling, UAV, D-InSAR, SBAS, and the results after integration. The horizontal axis represents the identification numbers of the monitoring points, while the vertical axis indicates the amount of subsidence.

Tables 5 and 6 present the maximum absolute error, average absolute error, and root mean square error for the UAV, D-InSAR, SBAS, and fused data along the inclination and strike lines, using level monitoring results as reference values. The superiority of the fused monitoring results over individual methods is evident from these comparisons.

Discussion

The experimental findings indicate that the monitoring techniques—UAV, D-InSAR, and SBAS—each have unique advantages and vary in effectiveness across different subsidence areas. Specifically, while UAVs are not precise in delineating the subsidence basin boundary, they provide results closest to reality with the least overall error. D-InSAR and SBAS, hindered by incoherence, struggle with large-gradient deformations and yield subsidence basins significantly different from actual observations.

In the central subsidence area, UAV monitoring exhibits the highest precision. Consequently, it can be considered that UAVs possess the most effective monitoring capability in the central subsidence area. D-InSAR successfully measured subsidence at all monitoring points within the area; however, its results exhibited significant deviations from the leveling measurements, with a root-mean-square error exceeding 1 m. Consequently, this study deduced that D-InSAR is not effective for monitoring central subsidence area. SBAS struggles to detect enough continuous high-coherence points for comprehensive monitoring. Even with Kriging interpolation applied to SBAS data, the resulting large errors suggest its unsuitability for accurate monitoring in the central subsidence area. D-InSAR outperforms both UAV and SBAS in the moderate subsidence area in terms of its lower maximum absolute error, average absolute error, and root mean square error within the monitoring results, regarding monitoring prowess. Therefore, D-InSAR is more efficacious in areas experiencing moderate subsidence. In the moderate subsidence area, the monitoring accuracy of both UAV and SBAS is relatively limited. Notably, SBAS lacks the capability to detect subsidence at all designated monitoring points within this area. In the peripheral subsidence area, the monitoring results of SBAS exhibit the least error, suggesting that SBAS possesses superior monitoring capabilities in these regions. However, the error advantage of SBAS over D-InSAR is not significantly pronounced, indicating that the actual precision enhancement of SBAS compared to D-InSAR is limited. In edge subsidence areas, the monitoring accuracy of InSAR is noticeably superior to that of UAVs, reflecting the advantage of InSAR technology in detecting minute deformations. In practical data processing, SBAS, as compared to D-InSAR, enables more efficient and convenient acquisition of long-term subsidence data and average subsidence rates.

Surface mining subsidence in the mining area is classified into four stages based on the characteristics of subsidence speed: pre-mining stability period, accelerated subsidence period, decelerated subsidence period, and post-mining stability period. For the accelerated subsidence period and decelerated subsidence period, the surface deformation gradient above the working face is large, allowing the subsidence area to be divided into: the edge subsidence zone, moderate subsidence zone, and central subsidence zone, which are monitored and integrated using the methods proposed in this study. For the pre-mining stability period and post-mining stability period, the surface subsides slowly and steadily. Due to the inability of UAV technology to detect minor deformations, it is more appropriate to use D-InSAR and SBAS technologies to monitor the initial movement of the surface and the slow, stable subsidence after mining. In terms of surface coverage, the central subsidence zone generally consists of farmland and sparse villages, which are conducive to drone monitoring; the edge subsidence zone consists mostly of industrial squares and urban areas, where the area is larger and the deformation smaller, thus obtaining more high-coherence points, making SBAS monitoring more suitable. Moderate subsidence zones, often comprising abandoned villages and farmlands, may not yield effective subsidence data from SBAS, hence overlaying the subsidence results from multiple D-InSAR monitoring sessions is a superior method.

Both InSAR and UAV technologies can obtain high-resolution and high-accuracy areal subsidence data at low cost. Apart from the difference in accuracy, the cost of InSAR technology is lower compared to UAV, making it more suitable for monitoring large-scale ground subsidence; UAV technology, compared to InSAR, is more flexible and offers a more diverse form of data, serving as a good complement to InSAR technology in the field of mining area surface subsidence monitoring. Regarding the bottleneck issue of monitoring the central subsidence area with D-InSAR and SBAS, this study has conducted ample experiments based solely on Sentinel data. In the future, attempts will be made to obtain synthetic aperture radar datasets with longer wavelengths or shorter revisit periods to further research in monitoring large-gradient deformation in mining areas.

Conclusion

This research conducts a comprehensive evaluation of the deformation monitoring capabilities of D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV at the Anhui Banji Coal Mine’s 110,801 working face. Through both holistic and segmented quantitative analyses, a novel approach for merging multi-source monitoring data is proposed. The major conclusions derived from this study are as follows:

Observational data reveals that subsidence and surface alterations diminish with increasing distance from the working face, consistent with established principles of ground movement and deformation associated with mining activities. Overall, the subsidence basin monitored by UAV aligns most closely with actual results, exhibiting the smallest overall error, whereas the monitoring results of SBAS have the largest overall error. In specific subsidence areas, UAV exhibits the highest accuracy in the central subsidence area, underscoring its optimal monitoring capability. In the moderate subsidence area, D-InSAR surpasses UAV and SBAS in terms of lower maximum and mean absolute errors, along with root mean square error, highlighting its efficacy. Conversely, SBAS shows minimal error in the peripheral subsidence area, indicating its proficiency there. Distinctively, D-InSAR and SBAS errors trend higher towards the center, while UAV monitoring maintains relatively stable error levels across various areas. Utilizing UAV technology for central subsidence area monitoring, D-InSAR for moderate zones, and SBAS for peripheral areas, the integrated results from these methods yield data with enhanced accuracy. The combined data’s maximum root mean square error, mean absolute error, and overall root mean square error significantly surpass the results from single monitoring methods. Hence, leveraging the synergistic strengths of D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV technologies enables a more intuitive and precise monitoring of mining subsidence basins. This integrated approach not only facilitates unmanned monitoring but also significantly contributes to the ecological and environmental protection in mining regions.

Data availability

The radar data were obtained from European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel-1A satellite (https://search.asf.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 15 May 2023)). The external Digital Elevation Model (DEM) utilized was derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 15 May 2023)).

References

Przyłucka, M., Herrera, G., Graniczny, M., Colombo, D. & Béjar-Pizarro, M. Combination of conventional and advanced DInSAR to monitor very fast mining subsidence with TerraSAR-X data: Bytom City (Poland). Remote Sens. 7, 5300–5328 (2015).

Yunjia, W. Research progress and prospect on ecological disturbance monitoring in mining area. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 46, 1705 (2017).

Yang, Z. et al. Deriving dynamic subsidence of coal mining areas using InSAR and logistic model. Remote Sens. 9, 125 (2017).

Lollino, G. et al. Engineering Geology for Society and Territory-Volume 5: Urban Geology, Sustainable Planning and Landscape Exploitation. (Springer, 2014).

Ou, D., Tan, K., Du, Q., Chen, Y. & Ding, J. Decision fusion of D-InSAR and pixel offset tracking for coal mining deformation monitoring. Remote Sens. 10, 1055 (2018).

Fan, H. et al. Mining large-gradient subsidence monitoring using D-InSAR optimized by GNSS. Imaging Sci. J. 69, 207–218 (2021).

Klein, E. et al. A comprehensive analysis of the Illapel 2015 Mw8. 3 earthquake from GPS and InSAR data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 469, 123–134 (2017).

Budetta, P., Nappi, M., Santoro, S. & Scalese, G. DinSAR monitoring of the landslide activity affecting a stretch of motorway in the Campania region of Southern Italy. Transp. Res. Procedia 45, 285–292 (2020).

Hou, Z. et al. Dynamic prediction model of mining subsidence combined with D-InSAR technical parameter inversion. Environ. Earth Sci. 81, 307 (2022).

Wang, L., Teng, C., Jiang, K., Jiang, C. & Zhu, S. D-InSAR monitoring method of mining subsidence based on Boltzmann and its application in building mining damage assessment. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 26, 353–370 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Integration of DInSAR-PS-stacking and SBAS-PS-InSAR methods to monitor mining-related surface subsidence. Remote Sens. 15, 2691 (2023).

Liu, Y. & Zhang, J. Integrating SBAS-InSAR and AT-LSTM for time-series analysis and prediction method of ground subsidence in mining areas. Remote Sens. 15, 3409 (2023).

Shi, M. et al. Improving boundary constraint of probability integral method in SBAS-InSAR for deformation monitoring in mining areas. Remote Sens. 13, 1497 (2021).

Liu, Z., Mei, G., Sun, Y. & Xu, N. Investigating mining-induced surface subsidence and potential damages based on SBAS-InSAR monitoring and GIS techniques: A case study. Environ. Earth Sci. 80, 817 (2021).

Zhai, M., Liu, Q., Tao, Q. & Liu, G. SBAS InSAR subsidence monitoring for mining areas based on levelling constraints. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2620, 012003 (2023).

Lee, S. & Choi, Y. Reviews of unmanned aerial vehicle (drone) technology trends and its applications in the mining industry. Geosyst. Eng. 19, 197–204 (2016).

Zhao, J., Yang, X., Zhang, Z., Niu, Y. & Zhao, Z. Mine subsidence monitoring integrating DS-InSAR with UAV photogrammetry products: Case studies on Hebei and Inner Mongolia. Remote Sens. 15, 4998 (2023).

Erenoglu, O. Uav for 3d morphological mapping applications: A case study of koru mining site, Canakkale, NW Turkey. Teh. Vjesn. 28, 1044–1050 (2021).

Dawei, Z., Lizhuang, Q., Demin, Z., Baohui, Z. & Lianglin, G. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry technology for dynamic mining subsidence monitoring and parameter inversion: A case study in China. IEEE Access 8, 16372–16386 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Accuracy verification and correction of D-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR in monitoring mining surface subsidence. Remote Sens. 13, 4365 (2021).

Pawluszek-Filipiak, K. & Borkowski, A. Integration of DInSAR and SBAS Techniques to determine mining-related deformations using sentinel-1 data: The case study of Rydułtowy mine in Poland. Remote Sens. 12, 242 (2020).

Wang, S., Bai, Z., Lv, Y. & Zhou, W. Monitoring extractive activity-induced surface subsidence in highland and alpine opencast coal mining areas with multi-source data. Remote Sens. 14, 3442 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Research on the applicability of DInSAR, stacking-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR for mining region subsidence detection in the datong coalfield. Remote Sens. 14, 3314 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Surface subsidence monitoring induced by underground coal mining by combining DInSAR and UAV photogrammetry. Remote Sens. 14, 4711 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. A novel method of monitoring surface subsidence law based on probability integral model combined with active and passive remote sensing data. Remote Sens. 14, 299 (2022).

Zhu, M. et al. Prediction parameters for mining subsidence based on interferometric synthetic aperture radar and unmanned aerial vehicle collaborative monitoring. Appl. Sci. 13, 11128 (2023).

Govil, H. & Guha, S. Underground mine deformation monitoring using synthetic aperture radar technique: A case study of Rajgamar coal mine of Korba Chhattisgarh, India. J. Appl. Geophys. 209, 104899 (2023).

Shen, C., Zhou, S., Luo, X., Zhang, Y. & Liu, H. Using DInSAR to inventory landslide geological disaster in Bijie, Guizhou, China. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1024710 (2023).

Ting-Chen, J. Ameliorative minimum cost flow algorithm for phase unwrapping. Procedia Environ. Sci. 10, 2560–2566 (2011).

Tao, Q. et al. Accuracy verification and evaluation of small baseline subset (SBAS) interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) for monitoring mining subsidence. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 54, 642–663 (2021).

Ma, F. & Sui, L. Investigation on mining subsidence based on sentinel-1A data by SBAS-InSAR technology—Case study of Ningdong Coalfield, China. Earth Sci. Res. J. 24, 373–386 (2020).

Wang, H., Li, K., Zhang, J., Hong, L. & Chi, H. Monitoring and analysis of ground surface settlement in mining clusters by SBAS-InSAR technology. Sensors 22, 3711 (2022).

Siebert, S. & Teizer, J. Mobile 3D mapping for surveying earthwork projects using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) system. Autom. Constr. 41, 1–14 (2014).

Colomina, I. & Molina, P. Unmanned aerial systems for photogrammetry and remote sensing: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 92, 79–97 (2014).

Tan, H., Yu, X., Zhu, M., Guo, Z. & Chen, H. Deformation monitoring and spatiotemporal evolution of mining area with unmanned aerial vehicle and D-InSAR technology. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 1–12 (2022).

Yucel, M. A. & Turan, R. Y. Areal change detection and 3D modeling of mine lakes using high-resolution unmanned aerial vehicle images. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 41, 4867–4878 (2016).

Long, N. Q. et al. Optimal choice of the number of ground control points for developing precise DSM using light-weight UAV in small and medium-sized open-pit mine. Arch. Min. Sci. 66, 369–384 (2021).

Zebker, H. A. & Villasenor, J. Decorrelation in interferometric radar echoes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 30, 950–959 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Key Research and Development Program of Anhui Province, grant number 202104a07020014; Major science and technology projects of Anhui Province, grant number 202103a05020026; Anhui University of Science and Technology Talent Introduction Research Startup Fund, grant number 2022yjrc26; Anhui Province Universities Natural Science Research Project, grant number 2023AH051190; Coal Industry Engineering Research Center of Mining Area Environmental and Disaster Cooperative Monitoring(Anhui University of Science and Technology), grant number KSXTJC202207.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z., X.Y. and H.T. wrote the main manuscript text, J.Y. prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, M., Yu, X., Tan, H. et al. Integrated high-precision monitoring method for surface subsidence in mining areas using D-InSAR, SBAS, and UAV technologies. Sci Rep 14, 12445 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63400-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63400-5

This article is cited by

-

Subsidence characteristics and mechanism study of Hongqinghe Mine based on multi source data

Environmental Earth Sciences (2026)

-

Efficient unmanned aerial vehicle inspection and management of transmission lines in modern electric power enterprises

Energy Informatics (2025)

-

Mining Subsidence Based on Integrated SBAS-InSAR and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Technology

Journal of Ocean University of China (2025)

-

Instability precursors of Liangshui landslide detected by integrating InSAR and DIC technologies

Landslides (2025)

-

The coordinated settlement patterns between loose aquifer loss and surface ground due to groundwater depletion

International Journal of Coal Science & Technology (2025)