Abstract

The Lower Jurassic Ziliujing Formation in China’s Sichuan Basin is a significant shale target for exploration; however, the strong heterogeneity of the properties of organic matter (OM) in shale makes it challenging to identify the target area for exploration, and the mechanism of OM enrichment is still unclear. Furthermore, the mechanisms of the response of the Da’anzhai member to the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T-OAE) are controversial. Previous studies have focused on sedimentary facies analysis based on mineralogy and elemental abundances and have provided minimal information about organic geochemistry, which adds to the challenge of deeply understanding the influence of the T-OAE on the molecular geochemical characteristics of the Da’anzhai member. In this study, the Da’anzhai member of the Lower Jurassic Ziliujing Formation in the Langzhong area, Sichuan Basin, is studied via X-ray diffraction, total organic carbon, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, organic carbon isotope, organic petrographical and pyrolysis analyses. To accurately identify the trend of the paleosedimentary environmental proxies, the Mann‒Kendall test is utilized to identify the trend of the data. Our results show that the Da’anzhai shale was deposited in a dysoxic transitional environment to an intermittent reducing environment with freshwater to brackish conditions. The response to the T-OAE can be identified in the middle and upper parts of the middle submember and the bottom of the upper submember of the Da’anzhai member. The T-OAE influenced the redox conditions, salinity, and OM origins during deposition in the middle of the Da’anzhai member, which resulted in the enrichment of OM. The abnormally high C30 diahopane/C30 hopane (C30D/C30H) ratio can be considered a potential proxy for locating the section of strata that responded to the T-OAE in the Da’anzhai member. In the study area, the mechanism of the response of the Da’anzhai shale to the T-OAE manifested as an improvement in hydrological cycling rather than a marine incursion. Our study provides new information that deepens the understanding of the mechanisms of the response of lacustrine shales to oceanic anoxic events from the perspective of molecular organic geochemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shale oil is an unconventional petroleum resource with considerable global reserves and is regarded as an important source of energy. It is estimated that the global recoverable amount of shale oil is 618 × 108 t1, which has attracted the attention of people in academia and industry2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Achievements in exploration provide a rationale and impetus for studying the formation mechanisms of organic-rich shales in lacustrine systems. The Da’anzhai member of the Jurassic Ziliujing Formation in the Sichuan Basin is a crucial target of lacustrine shale oil exploration12,13. Previous studies have confirmed that the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T-OAE) is recorded in the Da’anzhai Member of the Sichuan Basin14,15. Some studies have also investigated the formation mechanisms of organic-rich shales in the Da’anzhai member14,16,17. However, the majority of these investigations rely on inorganic geochemical methods, with limited attention given to molecular geochemistry15. Compared with shales deposited in marine environments, lacustrine shales exhibit greater heterogeneity18. Consequently, the lack of molecular geochemical studies hinders a clear understanding of the influence of the T-OAE on the Da’anzhai member of the Sichuan Basin from the perspective of organic geochemistry.

Oceanic anoxic events (OAEs) represent significant vertical and horizontal expansions of oxygen minimum zones in most oceans in a short geological time (< 1 Myr)14,19,20. OAEs are typically global events; therefore, they are a vital research subject in earth system sciences. OAEs cause global disturbances in ocean-to-atmosphere systems14. Lacustrine sediments are sensitive to paleoclimate changes and can provide higher-resolution archives than marine sediments18. Therefore, lacustrine sedimentary systems provide crucial material for researching associated OAEs. Recently, lacustrine sedimentary systems associated with OAEs have attracted considerable attention from researchers14,21,22,23. Xu et al.21 indicated that the depositional age of the Da’anzhai member is ca. 180.3 Ma, which is consistent with the Toarcian period. Although previous studies have attempted to identify the response of Da’anzhai member to the T-OAE and determine its underlying mechanisms14,21, controversies about the response mechanisms still exist. Xu et al.21 hypothesized that marine incursions directly influenced the Da’anzhai member in the Sichuan Basin, whereas other researchers have argued that the response to OAEs in lacustrine sedimentary systems is primarily sourced from improvements in hydrological cycling14,22,23. Furthermore, previous studies have primarily focused on sedimentary facies analysis based on mineralogy and elemental abundance but have provided minimal information about organic geochemistry.

Differences in shale depositional environments (e.g., redox conditions, water column salinity, and organic matter sources) influence their organic matter (OM) geochemical characteristics (e.g., OM abundance and kerogen type), which determine the exploration potential of shale24,25. Therefore, accurate reconstruction of paleosedimentary environments is crucial for understanding OM enrichment in the shales deposited in lacustrine systems. Currently, OAE records have been identified in several lacustrine basins14,17,26,27. Undoubtedly, OAEs have significant impacts on OM enrichment in lacustrine shales, but the specific mechanisms involved still require further elucidation. Current methods for reconstructing paleosedimentary environments rely on organic (e.g., biomarkers) and inorganic (e.g., redox-sensitive elemental contents and ratios) geochemical methods. Biomarkers record crucial information about shales, such as OM sources and depositional environments, and are dependable representatives for the reconstruction of the paleosedimentary environment28. In this study, we collected borehole samples from the Langzhong area of the Sichuan Basin, conducted systematic OM mineralogical and organic geochemical analyses, and characterized the geological and geochemical features of the Da’anzhai shale. Moreover, paleosedimentary environments were reconstructed based on biomarkers, OM accumulation mechanisms were summarized, and the mechanism of the influence of the T-OAE on lacustrine systems was elucidated. The results of our study complement the molecular geochemical characteristics of the Sichuan Basin during the T-OAE period and provides new information that deepens the understanding of the mechanisms of the response of lacustrine shales to OAEs from the perspective of molecular organic geochemistry. Furthermore, our results provide a theoretical basis for the exploration of Jurassic lacustrine shale oil in the Sichuan Basin.

Geological setting

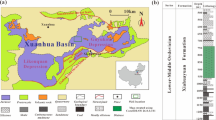

The Sichuan Basin in China is petroliferous, has abundant petroleum resources and potential for shale oil exploration, and has an area of 18 × 104 km2 (Fig. 1a)29. Based on the tectonic features, six substructural belts can be identified (Fig. 1a). Lacustrine deposition in the Sichuan Basin started during the Triassic30, and the petroleum-forming systems included the Triassic Xujiahe Formation and the Lower Jurassic Ziliujing and Lianggaoshan Formations. The Jurassic strata comprise the Ziliujing, Lianggaoshan, Shaximiao, Suining, and Penglaizhen Formations31. The sedimentary environment changed from a fluvial–lacustrine system to a shallow and semideep lake system from the deposition of the Triassic Xujiahe Formation to the Jurassic Ziliujing Formation30. The Lower Jurassic Ziliujing Formation contains four members: the Zhenzhuchong, Dongyuemiao, Ma’anshan, and Da’anzhai members. The lithology of the middle submember of the Da’anzhai member is gray–black calcareous shale interbedded with limestone, and the upper and lower submembers comprise coquina interbedded with gray mudstone, siltstone, and muddy siltstone (Fig. 1b). The study area is in the center of the Sichuan Basin and is part of the Northern Sichuan Lower and Flat Fold Belts.

Comprehensive geological figure of the study area in the Sichuan Basin (modified from reference7). (a) Tectonic units of the Sichuan Basin and the location of the study area. (b) Strata column of Da’anzhai member in the study area.

Data and methods

Samples and experiments

Thirty-six samples were collected from the Da’anzhai member in borehole LY1 in the Langzhong area. For the middle submember of the Da’anzhai member, the majority of the samples were collected from dark gray and black shales. However, for the upper and lower submembers, the lithology of the collected samples comprised dark gray mudstone, coquina, and siltstone. The samples were evaluated using X-ray diffraction (XRD), total organic carbon (TOC), gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), organic carbon isotope, and pyrolysis analyses. All experiments were conducted at the SINOPEC Wuxi Institute of Petroleum Geology.

Thirty-six samples were crushed and treated with a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer for XRD analysis, and the working voltage and current were 35 kV and 30 mA, respectively. In this study, the organic geochemistry was evaluated via TOC, pyrolysis, GC‒MS, and organic carbon isotope analyses. Thirty-six samples were crushed to 200 mesh and treated with hydrochloric acid. The inorganic carbon was removed, and the samples were analyzed using a Leco CS230 carbon/sulfur analyzer. The δ13Corg values were obtained using a Finnigan MAT 253 mass spectrometer and are reported relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite standard. After being evaluated by replicate measurements, the precision of the organic carbon isotopic analysis was better than ± 0.01‰. Organic petrographic observation was conducted using a Leica DM4500P polarizing microscope equipped with a 50 × oil immersion objective, through which the maceral compositions were identified.

A cryogenic crushing preparation technique was used to prevent the evaporation of light hydrocarbons (details about this technique can be found in Wang et al.7. Twenty-eight samples were selected for pyrolysis analysis using a Rock–Eval 6 pyrolysis instrument. The volatile hydrocarbon content (S1), pyrolyzed hydrocarbon content (S2), and maximum pyrolysis yield (Tmax) were obtained from the analyses.

Thirty-six samples were pretreated by Soxhlet extraction using chloroform:methanol (87:13, v/v) as the extraction solvent, and the extracted hydrocarbons were separated into saturated hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, resin, and asphaltene. The saturated hydrocarbons were analyzed using an Agilent 6890/5973 GC‒MS using DB-5MS. The initial temperature of the GC oven was 80 °C, which was maintained for 2 min. Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 230 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min and then to 310 °C at a rate of 2 °C/min. The temperature was maintained at 310 °C for 15 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas. The ions were produced using the electron ionization (EI) technique, where the EI temperature was 230 °C, and the scan range was 50–550 (m/z) for the full scan and selective ion monitoring modes. The biomarker ratios of this study were obtained by using the peak areas in the chromatograms.

Methods

Kerogen type index

For quantifying the kerogen type, the type index (TI) of kerogen obtained by organic petrographical analysis was determined in this study32,33, and the method of calculation is shown in Eq. (1). TI values less than 0, 0–40, 40–80, and greater than 80 represent type I, II1, II2, and III kerogen, respectively.

where S, E, V, and I are the proportions of sapropelite, exinite, vitrinite, and inertinite in the kerogen, respectively.

Statistical methods for quantifying the trend of data

In some studies, the identification of trends in geological data primarily depends on direct observation, which may result in trend misjudgement and data misinterpretation. To validate the presence of trends in our data, in this study, two statistical methods were employed: linear regression and the Mann‒Kendall test. Linear regression can clearly indicate whether the data trend upward or downward. For data exhibiting fluctuating features, we treated the fluctuating data as time series data and applied the Mann‒Kendall test to identify trends. This method is simple and effective because it does not require specific distributions of data and is insensitive to outliers, allowing it to accurately and quantitatively characterize the trends of the data. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the Mann‒Kendall test, this study presented two statistical parameters: the standardized normal test statistic (z value) and the p value. The z value indicates the significance of the trend, with an absolute value greater than 1.96 (or 2.58) indicating a significant trend. The p value is used to evaluate the significance of the statistical results and to determine whether the null hypothesis can be rejected. According to the Mann‒Kendall test, a p value less than 0.05 indicates the presence of a trend in the data. It is important to note that while our study still involves subjectivity in the selection of samples for trend construction, we have bolstered the scientific significance of our trends by employing statistical methods to enhance the reliability of our results.

Results

Petrological features and mineral composition

Figure 2 shows the petrologic features of the Da’anzhai member. The lithology of the Da’anzhai member includes siltstone, muddy siltstone, mudstone, shale, calcareous shale, coquina, and limestone. The samples’ colors are gray to dark gray, except for the coquina, which is white to light gray. The siltstone and muddy siltstone primarily contain grains such as quartz and feldspar, with subangular shapes and good sorting (Fig. 2a). The coquina primarily contains bioclastic and calcareous minerals, but clay minerals can also be detected (Fig. 2c). The primary difference between shale and calcareous shale is the bioclastic content. In the calcareous shale, numerous oriented bioclastics can be observed (Fig. 2f), and for other shales, the bioclastic contents are significantly lower than those in the calcareous shale (Fig. 2b, d, and i). The mudstones exhibit lower OM contents and higher grain contents than the shales (Fig. 2h and i). Combined with the stratigraphic and sedimentary facies results of Liu et al.14, the lithological trend of the Da’anzhai member in the study area records a complete shallowing–deepening–shallowing cycle.

Microscopies showing the lithology of Da’anzhai shale. (a) upper submember, 2891.85 m, siltstone; (b) upper submember, 2898.23 m, shale; (c) upper submember, 2899.92 m, coquina; (d) middle submember, 2909.80 m, shale; (e) middle submember, 2917.54 m, calcareous shale; (f) upper submember, 2923.89 m, siltstone; (g) lower submember, 2957.24 m, siltstone; (h) lower submember, 2951.94 m, mudstone; (i) upper submember, 2957.24 m, mudstone.

Table 1 shows the mineral composition. The clay minerals dominate the mineral composition of the Da’anzhai shale (the average content is 43.5%), and the middle submember has the highest average clay mineral content. The siliceous mineral contents in the Da’anzhai shale range from 3.5 to 56.6% (average of 32.3%), and the siliceous minerals are concentrated in the upper submember. The primary siliceous mineral in the sample is quartz, whereas feldspars (potassium feldspar and plagioclase) are present in lower amounts. The carbonate contents range from a trace (< 1%) to 90.0% (average 18.9%) and are highest in the lower submember. The main carbonate mineral is calcite, with minor quantities of siderite and dolomite. Aragonite was detected in only three samples, with a maximum content of 34.4%.

Bulk geochemical and organic petrographic features

The TOC content and pyrolysis are standard indices used to evaluate the quality of shales34,35; our results are shown in Table 2. The TOC contents and S1 + S2 values are plotted in Fig. 3. The TOC contents of the Da’anzhai shale range from 0.10 to 3.63% (average of 1.61%). The maximum and highest mean TOC values appear in the middle submember. The S1 + S2 values vary from 0.21 to 16.53 mg HC/g rock for the Da’anzhai shale (average of 6.65 mg HC/g rock), the S3 values range from 0.76 to 2.91 mg HC/g rock, and the distribution patterns of S1 + S2 and S3 are similar to those of the TOC content. The production index (PI) values of the Da’anzhai shale range from 0.20 to 0.56, the average value is 0.41, and the S2/S3 ratios vary from 0.17 to 3.91.

The hydrogen index (HI = S2/TOC × 100) and the Tmax values obtained from pyrolysis are used to identify the kerogen types of the shales36 (Fig. 3). The HI values of the Da’anzhai shale are 27.87–283.33 mg HC/g TOC (average of 184.72 mg HC/g TOC). The Tmax values are mainly in the range of 440–460 °C. Our results show that type II2 and type III kerogens dominate the Da’anzhai shale, and these shales are in the mature to high–mature stage.

The δ13Corg values of the Da’anzhai shale in our study area range from − 29.8 to − 23.1‰, and our data show a negative carbon isotope excursion of 3.4‰, starting at a depth of 2936.05 m. The minimum δ13Corg value reaches − 29.8‰ at a depth of 2915.12 m and increases to − 23.1‰ at 2889.67 m. Table 2 and Fig. 4 present the detailed data and vertical distribution of the δ13Corg values.

The organic petrographic analyses of the Da’anzhai shale are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 5, and there is almost no sapropelite or inertinite in the samples. The exinite shows structureless characteristics (Fig. 5c). The vitrinite includes structural and structureless vitrinite (Fig. 5a, b, d). The main differences in the dataset in this study are the proportions of exinite and vitrinite, and the TI values of the Da’anzhai shale range from − 42.5 to 11.5.

Molecular geochemistry analysis

Figure 6 shows the total ion and representative chromatograms of the saturated hydrocarbons of the Da’anzhai shale. Table 4 shows some biomarker features. Normal alkanes are in the n-C13–C37 range. Some samples show unimodal distributions with low–moderate-molecular-weight n-alkane peaks (such as the n-C16 and n-C19 peaks, Fig. 6a1), whereas other samples exhibit bimodal distributions (Fig. 6 (b1)). The first peak corresponds to low-molecular-weight (< n-C20) n-alkanes (n-C19), and the second peak corresponds to moderate-molecular-weight (n-C21–n-C25) n-alkanes (n-C23). The abundance of the front peak is greater than that of the trailing peak. The (nC21 + nC22)/(nC28 + nC29) ratios range from 0.52 to 3.07, and the terrigenous/aquatic ratios (TAR = (nC27 + nC29 + nC31)/(nC15 + nC17 + nC19))37 range from 0.25 to 3.21. The samples’ carbon preference index (CPI) and odd-to-even predominance (OEP) values are close to 1, showing no significant differences among the different submembers of the Da’anzhai member samples. The pristane/phytane (Pr/Ph) ratios are 0.82–1.39.

Common tricyclic terpanes (TTs, m/z 191), namely, C19TT–C26TT, are present in the extracted hydrocarbons. Moreover, high-carbon-number TTs (C28TT and C29TT, m/z 191) and C24 tetracyclic terpanes (TeT, m/z 191) are present (Fig. 6a2). The abundance of TTs varies considerably (Fig. 6a2 and b2). In most samples, the abundance of 18α(H)-22,29,30-C27 trisnorneohopane (Ts, m/z 191) is greater than that of 17α(H)-22,29,30-C27 trisnorneohopane (Tm, m/z 191), and the Ts/(Ts + Tm) ratios range from 0.31 to 0.88. C30 diahopanes (C30D, m/z 191) are detected in all the samples (Fig. 6a2), and the C30D/C30 hopane (C30H, m/z 191) ratios are 0.12–47.89. A high C30D/C30H ratio of the Da’anzhai member was also reported by Lu et al.38. Furthermore, C31 to C34 hopanes and gammacerane (Gam, m/z 191) are detected, and the Gam index (GI = Gam/C30H) values range from 0.10 to 19.11 (Table 5).

C27, C28, and C29 regular steranes and rearranged C27 steranes are present in all Da’anzhai member samples (m/z 217, Fig. 6 (a3) and (b3)). The relative proportions of C27, C28, and C29 regular steranes differ significantly among the various samples, and the (C27 + C28)/C29 ratios range from 1.12 to 3.63. The R and S isomers were evaluated in the C27–C29 steranes, and the C29 ααα 20S/(20S + 20R) and C29 αββ/(αββ + ααα) ratios range from 0.45 to 0.78 and 0.40–0.54, respectively (Table 5).

Discussion

Thermal maturity

Thermal maturity considerably influences the effectiveness of biomarkers as parameters for the depositional setting; hence, it is essential to characterize thermal maturity first. The Tmax values of the Da’anzhai shale in the study area are mainly in the range of 440–460 °C, and the variation in the Tmax value may be attributed to differences in the hydrocarbon content rather than variations in thermal maturity. The PI ratios are mainly in the range of 0.3–0.5. Moreover, previous studies have suggested that the vitrinite reflectance (Ro) values are mainly in the range of 1.0–1.2%33,39. Earlier Ro results and the Tmax values and PI ratios of our samples indicate that the Da’anzhai shales are in the mature to highly mature stage. The CPI and OEP values in our study area are approximately equal to 1, showing no odd–even predominance, indicating a mature stage of the Da’anzhai shale in the investigated area.

Furthermore, the high content of low-molecular-weight n-alkanes in most samples indicates that maturity influences biomarkers. The C29 αββ/(αββ + ααα) and C29 ααα 20S/(20S + 20R) data for the Da’anzhai shale in the study area indicate that all the samples have reached the mature stage; the high Ts/(Ts + Tm) values (mean value of 0.73) also indicate that they are the same.

Record of the T-OAE in the Da’anzhai member

Trend analysis of the data

Figure 4 and Table 6 summarize the trends of the data and corresponding statistical parameters. Linear regression was used to identify clear upward (indicated by red arrows) or downward (indicated by yellow arrows) trends, with correlation coefficient (R2) values calculated. For fluctuating data (indicated by the green arrows in Fig. 4), the R2 values of the linear regression are too low to reflect any trend (Table 6). In these cases, the Mann‒Kendall test is used to determine the z value and p value of the data. All the absolute z values are less than 1.96, and all the p values are greater than 0.05, indicating that there are no clear trends and that the data exhibit fluctuating characteristics. The above statistical data indicate that the trends of the paleosedimentary environmental proxies in our study are reliable.

Response of the Da’anzhai member to the T-OAE

The T-OAE was an oceanic anoxic event that occurred in the Toarcian period. The typical characteristic of the T-OAE is an apparent rapid negative organic carbon isotope excursion19,21. Our data show that the δ13Corg values of the Da’anzhai shale exhibit five obvious trends, and the data first show a negative trend (2950. 53–2958.21 m, trend 1 of δ13Corg) and then a fluctuation from 2938.35 to 2949.78 m (trend 2 of δ13Corg). The most noticeable negative carbon isotope excursion occurs between 2902.47 and 2936.05 m (trend 3 of δ13Corg), and the δ13Corg value reaches − 29.8‰ (the negative carbon isotope excursion range is 3.4‰). Then, at 2899.07 m, the δ13Corg value changes to a positive excursion (trend 4 of δ13Corg). In our study, the thickness of the most noticeable section of the negative carbon isotope excursion is approximately 36 m. The response of the T-OAE recorded in the Da’anzhai shale is characterized by a significant negative local excursion in the δ13Corg value14,21. In our research, the most noticeable section of negative carbon isotope excursion is located in the middle and upper parts of the middle submember and the bottom of the upper submember of the Da’anzhai member (Fig. 4). The lithology of this section is dark gray shale interbedded with limestone, and these petrographical features may indicate a deep paleowater depth. Moreover, the TOC content of the section with noticeable negative carbon isotope excursions remains high (Fig. 4, trend 2 of the TOC content). These phenomena correlate well with those of previous studies14. The δ13Corg values of the Da’anzhai member reported in previous studies are shown in Fig. 7. From west to east, three boreholes exhibit significant carbon isotope excursions. Among them, core A displays the most pronounced excursion, with an amplitude of approximately 4.3‰. The carbon isotope excursions in the LQ104X and LY1 wells are similar, with values of 3.8 and 3.4‰, respectively. The thicknesses of the carbon isotope excursion layers in cores A, LY1, and LQ104X are approximately 29.1, 33.6, and 30.8 m, respectively. According to previous discussions, the most notable negative carbon isotope excursions of the Da’anzhai shale in the study area (top at 2902.47 m and bottom at 2936. 05 m, trend 3 of δ13Corg) can be identified as the section that shows the response to the T-OAE, and sections above and below the section that shows the response to the T-OAE are defined as unassociated T-OAE sections. Additionally, our data confirm the presence of T-OAE records in the central and northern Sichuan Basin, supporting the conclusion from a prior study that a basin-wide response to the T-OAE is recorded in the Sichuan Basin14.

Paleosedimentary environmental reconstruction

OM origin

For lacustrine systems, primary productivity, redox conditions, and salinity are the essential parameters influencing OM accumulation24. In this section, different biomarkers are selected to reconstruct the paleosedimentary environment.

In this study, primary productivity in the water column is characterized by the type of OM; for example, the high contribution of aquatic organisms to kerogen may indicate high primary productivity. Rock–Eval pyrolysis effectively determines the kerogen type of OM40. Our results show that the OM of the Da’anzhai shale in the investigated area is type II2 and type III kerogen, indicating a mixed OM source of aquatic plankton and terrigenous higher plants. Moreover, organic petrographic observations indicate similar results: exinites are mainly sourced from aquatic algae, and a relatively high proportion of vitrinite in OM contributes to terrigenous higher plants. The distribution of the TI ratio is shown in Fig. 4, where the TI exhibits five apparent trends. Initially, the TI shows a decreasing trend, and in the section that shows the response to the T-OAE, it displays in increasing, a decreasing, and then an increasing trend (trend 2 to 4 of the TI). Furthermore, fluctuations in the δ13Corg value also signify changes in the source of OM. Generally, a negative excursion of the δ13Corg value is indicative of an increased proportion of aquatic organisms within the OM41,42. Consequently, the negative δ13Corg excursions observed in the section that shows the response to the T-OAE reinforce the findings from organic petrographic observations, supporting the interpretation of a significant shift in the origin of OM during this interval.

Molecular geochemical parameters, e.g., the n-alkane distribution, can also be used to assess the origins of OM43,44. C27 sterane is a marker of phytoplankton45, C28 is expected to be derived from phytoplankton containing chlorophyll46, and C29 sterane has various sources; in most cases, C29 sterane is derived from terrigenous higher plants47, while some researchers argue that C29 sterane may be derived from specific microalgae48,49. In this study, the ratio of steranes was used to characterize the OM source, e.g., a high (C27 + C28)/C29 sterane ratio indicates a high proportion of aquatic organisms accumulating OM. The (C27 + C28)/C29 ratio of the Da’anzhai member samples shows seven vertical trends, initially showing a downward trend (trend 1), followed by an upward–downward–upward and a relatively stable trend (trends 2–5). Above the T-OAE, the (C27 + C28)/C29 ratio exhibits a decreasing trend (trend 6). Combining pyrolysis tests, organic petrographical experiments, δ13Corg values, and biomarker data, the results indicate that OM was primarily sourced from the mixed contribution of aquatic algae and terrigenous higher plants. However, the sources of OM and primary productivity still exhibit certain differences. During the T-OAE period, aquatic organisms contributed more to OM, and the primary productivity was relatively high.

Redox conditions

Most of the samples indicate a dysoxic environment with Pr/Ph ratios greater than 1, while some samples with low Pr/Ph ratios indicate an intermittent reducing environment, demonstrating the impact of environmental fluctuations on lacustrine sedimentary systems (Table 4). The Pr/Ph ratio shows a decreasing trend in the section that shows the response to the T-OAE (Fig. 4, trend 2), followed by an obvious increasing trend above the T-OAE (trend 3). Our data indicate that the Da’anzhai shale experienced dysoxic to anoxic conditions during the T-OAE period, and the results reflect the impact of the T-OAE on the redox conditions of the Da’anzhai member.

415Salinity and abnormal abundance of diahopanes

Salinity is another crucial factor affecting OM accumulation. Liu et al.14 used trace elements to evaluate the paloesalinity of the Da’anzhai member and concluded that the Da’anzhai member was primarily deposited in freshwater to brackish conditions. In most cases, the vertical stratification of the water column is caused by differences in salinity conditions. Therefore, the GI represents the water column salinity. A GI greater than 0.1 indicates water column stratification50,51. Our GI data show anomalously high values with a maximum of 19.11, indicating the high salinity of the water column. However, this result contradicts the results of previous studies involving inorganic geochemistry (Sr/Ba ratios ranging from 0.18 to 0.26, indicating freshwater to brackish salinity conditions)14 and molecular geochemistry (GI values ranging from 0.05 to 0.23)15. Subsequently, the samples showing anomalously high GI values exhibit low C30H and high C30D values (Table 5 shows high C30D/C30H values). Therefore, the abnormally high GI does not indicate water column stratification and salinity but rather a low C30H value. Earlier studies have reported several cases in which source rocks had abnormally high C30D/C30H ratios in the mature stage, such as the Permian Pebbley Beach Formation in the Sydney Basin52, the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin53, and the Jurassic Xinhe Formation in the Yabulai Basin54. Researchers have proposed that abnormally high C30D/C30H values may be related to thermal maturity, the clay mineral content, salinity, and redox conditions52,53,54,55,56. At present, there is no accurate explanation for the abnormally high C30D/C30H ratios in rock extracts and oils57. From the data presented in Fig. 4, we can infer the reason for the abnormally high C30D/C30H ratios. First, the C30D/C30H values exhibit a similar trend to that of the clay mineral content, which may indicate that the catalysis of clay minerals plays an important role in the formation of these diahopanes. In the section that shows the response to the T-OAE, high clay mineral contents promoted the formation of diahopanes, which is consistent with findings from previous studies15. Additionally, the Pr/Ph ratio in this study indicates a suboxic environment during the deposition of the Da’anzhai member, which facilitated the formation of diahopanes52,57. It is important to note that Reolid et al.15 did not report abnormally high C30D/C30H values or abnormally low GI values in the study of the Da’anzhai member, likely due to the lower thermal maturity of their samples (Ro values of approximately 0.82–0.85%). C30D is more stable than C30H at high thermal maturity58, explaining the discrepancy in molecular geochemical characteristics between our study and that of Reolid et al.15. This discrepancy further underscores the significant heterogeneity in the molecular geochemical characteristics of lacustrine shales. Regardless of the generation mechanism of C30D, the abnormally high GI values are not derived from the high Gam content. Therefore, the GI is not a reliable indicator for assessing salinity conditions in this context. Our study emphasizes the need for caution when using the GI as a salinity proxy in environments characterized by clay mineral enrichment, high thermal maturity, and suboxic conditions. Furthermore, the concurrent findings of the increased clay mineral content in the section that shows the response to the T-OAE in the Da’anzhai member, as observed in both our study and that of Reolid et al.15, suggest that an abnormally high C30D/C30H ratio may serve as a potential proxy for pinpointing the section that shows the response to the T-OAE within this geological context.

Earlier studies have shown that an extended tricyclic terpane ratio (ETR = (C28TT + C29TT)/(C28TT + C29TT + Ts)) can characterize the salinity of lake water59,60. Table 5 shows the ETR data for the study area. The ETR values range from 0.27–0.71, indicating fluctuating salinity conditions. Combined with the Sr/Ba ratio of Liu et al.14, the salinity conditions in the Da’anzhai shale are mainly freshwater to brackish, and the ETR value can reflect the variation in salinity. The ETR data revealed four vertical trends (Fig. 4): decreasing values (trend 1) followed by consistently low values (trend 2). The later T-OAE exhibits increasing values (trend 3), after which the ETR values remain relatively high (trend 4).

Paleoenvironmental evolution of the Da’anzhai member

By integrating the above biomarker data, in this study, the sedimentary environment and evolutionary process of the Da’anzhai member in the study area are reconstructed. In the early Da’anzhai period, the lake was relatively small. The lake expanded from the lower to middle submembers, the sediment changed from coquina to black shale, the organic matter abundance increased (trend 1 of the TOC content), and the salinity of the water column decreased (trend 1 of the ETR). However, due to the increase in terrigenous influxes during this period (the clay mineral content increased, trend 1), the redox conditions did not shift to those of a reducing environment (trend 1 of Pr/Ph). This explanation is further supported by OM sources (trend 1 of the (C27 + C28)/C29 ratio and trend 1 of the TI). The middle submember of the Da’anzhai member was deposited mainly in a semideep lake to deep lake environment, and a significant negative excursion in the δ13Corg value (trend 3 of δ13Corg) occurred after 2936.05 m, corresponding to the terrigenous response of the Da’anzhai member to the T-OAE. During this period, the temperature and precipitation increased (Yang, (2019)61 reported an increase in the C-values in the section that shows the response to the T-OAE in boreholes in the central Sichuan Basin), the lake further expanded, and the salinity remained relatively low (trend 2 of the ETR). The redox conditions changed to those of a relatively reducing environment (trend 2 of Pr/Ph), which is consistent with the results revealed by MoEF and Corg/P data14. The anoxic environment and high clay mineral content may also promote the formation of C30D, resulting in abnormally high GI values. In the section that shows the response to the T-OAE, the TOC content remained relatively high (trend 2 of the TOC content). Moreover, the increase in the proportion of aquatic organisms in OM (trend 2 of the (C27 + C28)/C29 ratio and trend 2 of TI) may represent an increase in primary productivity in the water column, which is consistent with the significant improvement in authigenic Cu and Ni contents during the T-OAE period reported by Yang61. Although there were obvious fluctuations in primary productivity during the T-OAE period, such as trend 3 for the (C27 + C28)/C29 ratio and trend 3 for the TI, the primary productivity generally remained relatively high in the section that shows the response to the T-OAE (trends 4 and 5 for the (C27 + C28)/C29 ratio and trend 3 for the TI). Notably, in the late T-OAE, the salinity increased (trend 3 of the ETR), which may indicate a decrease in the paleowater depth of the lake. Although the size of the lake decreased, the redox conditions did not significantly fluctuate (trend 2 of Pr/Ph), which may be attributed to the high primary productivity in the water column. The δ13Corg values showed a significant positive excursion (trend 3 of δ13Corg), indicating the end of the T-OAE and significant changes in the sedimentary environment. At the end of the T-OAE, the primary productivity decreased (trend 6 of the (C27 + C28)/C29 ratio and trend 5 of the TI), leading to the anoxic environment changing to a dysoxic environment (trend 3 of the Pr/Ph), and a high salinity indicates a low paleowater depth (trend 4 of the ETR). The TOC content obviously decreased (trend 3 of the TOC content), and the sediments also changed from black shale to mudstone and limestone interbedded with sandstone.

Mechanism of the response to the T-OAE and its effect on OM accumulation

Global events cause significant changes in sedimentary environments and lead to variations in TOC contents25,62. Hence, the mechanisms of OM enrichment and variations in the TOC content in the Da’anzhai member are discussed in this section. As mentioned above, the redox environment, primary productivity, and salinity conditions changed significantly during the T-OAE period. This leads to a difference in the TOC content. Due to the change in the paleoclimate, the paleowater depth of the lake increased, and a relatively reducing environment formed. Moreover, the prosperity of aquatic organisms has led to the improvement of primary productivity, which is further conducive to the formation of a relatively reducing environment. Although the paleowater depth of the lake may have declined in the late T-OAE, the anoxic environment could still have been maintained due to the high primary productivity of the water column. In summary, the OM enrichment in the section that shows the response to the T-OAE was caused by the combination of the paleoclimate, redox conditions and primary productivity.

The mechanism of the response of lacustrine systems to OAEs has been the subject of intense research. Two hypotheses for the mechanism of the response of the T-OAE recorded in the Da’anzhai member, Sichuan Basin, exist: transgression and alteration of hydrological conditions14,21. As mentioned previously, controversies about response mechanisms still exist. Our data show that there was no direct marine influence on the Da’anzhai shale and that the alteration of hydrological conditions changed the paleosedimentary environment. As reported by Xu et al.21, marine incursions occurred in the middle of the T-OAE period, which is obviously different from the conclusion drawn from the ETR data in this paper. Moreover, although the ETR tended to increase in the late T-OAE (trend 3), the salinity did not decrease significantly until the end of the T-OAE (trend 4 of the ETR). Furthermore, Wang et al.33 reconstructed the paleoenvironment based on elemental geochemistry from the same strata in the LY1 borehole. Their findings indicate that during the T-OAE period, the Sr/Ba ratios ranged from 0.15 to 0.28, with an average of 0.21. This ratio suggests only slight fluctuations in salinity within the water column, indicating conditions ranging from freshwater to brackish. Additionally, as depicted in Fig. 4, an increase in the clay mineral content also signifies a heightened influx of terrigenous debris. Together, these phenomena challenge the hypothesis of a transgressive event during this period. Therefore, the response of the Da’anzhai shale to alteration by the T-OAE was manifested in hydrological conditions rather than marine incursions. This study revealed the mechanism of the lacustrine response of the Da’anzhai shale to the T-OAE from the perspective of molecular organic geochemistry.

Conclusions

The geological features of the Da’anzhai shales of the Lower Jurassic Ziliujing Formation were characterized. Three primary findings are listed as follows.

-

(1)

The TOC contents of the Da’anzhai shale are 0.10–3.63% (average of 1.61%). The Tmax data and biomarkers indicate that the shales are in the mature to highly mature stage, and pyrolysis data and organic petrographical analysis show that type II2 and type III kerogens dominate in the Da’anzhai shale.

-

(2)

Generally, the Da’anzhai shales were deposited in a dysoxic transitional environment to an intermittent reducing environment with freshwater to brackish conditions. The terrigenous response to the T-OAE can be identified in the middle and upper parts of the middle submember and the bottom of the upper submember of the Da’anzhai member (with depths of 2902.47–2936.05 m). The sedimentary environment of the T-OAE period was anoxic, with higher primary productivity than that of the unassociated T-OAE section. It is important to exercise considerable caution when using the GI as a proxy for assessing salinity in clay mineral enrichment, high thermal maturity, and suboxic environments. The abnormally high C30D/C30H ratio may serve as a promising proxy for identifying the section that shows the response to the T-OAE in the Da’anzhai member.

-

(3)

The T-OAE changed the redox conditions, salinity, and primary productivity during the depositional period in the middle of the Da’anzhai member, which further resulted in OM enrichment. In the study area, the improvement in hydrological cycling rather than marine incursions is the response of the Da’anzhai shale to the T-OAE.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ma, Y. S. et al. Geological characteristics and exploration practices of continental shale oil in China. Acta Geol. Sin. 96(1), 155–171 (2022) (in Chinese with English Abstract).

Ross, D. J. K. & Bustin, R. M. Characterizing the shale gas resource potential of Devonian-Mississippian strata in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin: Application of an integrated formation evaluation. AAPG Bull. 92, 87–125 (2008).

Jarvie, D. M. Shale resource systems for oil and gas: Part 2-shale-oil resource systems. In Shale Reservoirs Giant Resources for the 21st Century Vol. 97 (ed. Breyer, J. A.) 89–119 (American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoir, 2012).

Li, C. R., Pang, X. Q., Huo, Z. P., Wang, E. Z. & Xue, N. A revised method for reconstructing the hydrocarbon generation and expulsion history and evaluating the hydrocarbon resource potential: Example from the first member of the Qingshankou Formation in the Northern Songliao Basin, Northeast China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 121, 104577 (2020).

Li, M. W. et al. What are in pyrolysis S1 peak and what are missed? Petroleum compositional characteristics revealed from programed pyrolysis and implications for shale oil mobility and resource potential. Int. J. Coal Geol. 218, 103321 (2020).

Li, J. B., Wang, M., Jiang, C. Q., Lu, S. F. & Li, Z. Sorption model of lacustrine shale oil: Insights from the contribution of organic matter and clay minerals. Energy 260(1), 125011 (2022).

Wang, E. Z., Feng, Y., Guo, T. L. & Li, M. W. Oil content and resource quality evaluation methods for lacustrine shale: A review and a novel three-dimensional quality evaluation model. Earth Sci. Rev. 232, 104134 (2022).

Wang, E. Z. et al. Novel method for determining the oil moveable threshold and an innovative model for evaluating the oil content in shales. Energy 239, 121848 (2022).

Feng, Y. et al. Gas storage in shale pore system: A review of the mechanism, control and assessment. Pet. Sci. 20(5), 2605–2636 (2023).

Wang, Y. X. et al. Multiscale petrographic heterogeneity and their implications for the nanoporous system of the Wufeng-Longmaxi shales in Jiaoshiba area, Southeast China: Response to depositional-diagenetic process. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 132(7–8), 1704–1721 (2020).

Wang, Y. X. et al. Arid climate disturbance and the development of salinized lacustrine oil shale in the Middle Jurassic Dameigou Formation, Qaidam Basin, northwestern China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 577, 110533 (2021).

Feng, Y., Xiao, X. M., Wang, E. Z., Sun, J. & Gao, P. Oil retention in shales: A review of the mechanism. Controls Assess. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 720839 (2021).

Wang, E. Z. et al. Favorable exploration lithofacies and their formation mechanisms in lacustrine shales deposited under different salinity conditions: Insights into organic matter accumulation and pore systems. Energy Fuels 37(16), 11838–11852 (2023).

Liu, J. C. et al. Water-level and redox fluctuations in a Sichuan Basin lacustrine system coincident with the Toarcian OAE. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 558, 109942 (2020).

Reolid, M., Duarte, L. V., Mattioli, E. & Ruebsam, W. Carbon Cycle and Ecosystem Response to the Jenkyns Event in the Early Toarcian (Jurassic) 514 (Geological Society, 2021).

Qiu, Z. & He, J. L. Depositional environment changes and organic matter accumulation of Pliensbachian-Toarcian lacustrine shales in the Sichuan basin. SW China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 232, 105035 (2022).

Wang, E. Z. et al. Sedimentary differentiation triggered by the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event and formation of lacustrine shale oil reservoirs: organic matter accumulation and pore system evolution of the Early Jurassic sedimentary succession, Sichuan Basin, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 256, 105825 (2023).

Katz, B. & Lin, F. Lacustrine basin unconventional resource plays: Key differences. Mar. Pet. Geol. 56, 255–265 (2014).

Jenkyns, H. C. Geochemistry of oceanic anoxic events. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11, Q03004 (2010).

Them, T. R. et al. Thallium isotopes reveal protracted anoxia during the Toarcian (Early Jurassic) associated with volcanism, carbon burial, and mass extinction. PNAS 115, 6596–6601 (2018).

Xu, W. M. et al. Carbon sequestration in an expanded lake system during the Toarcian oceanic anoxic event. Nat. Geosci. 10, 129–134 (2017).

Liu, M. et al. Organic geochemistry of a lacustrine shale across the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (Early Jurassic) from NE China. Glob. Planet Change 191, 103214 (2020).

Jin, X. et al. The Jenkyns event (early Toarcian OAE) in the Ordos basin, North China. Glob. Planet Change 193, 103273 (2020).

Wu, Z. Y. et al. Sedimentary environment and organic enrichment mechanisms of lacustrine shale: A case study of the Paleogene Shahejie formation, Qikou Sag, Bohai Bay basin. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 573, 110404 (2021).

Wang, E. Z. et al. Depositional environment variation and organic matter accumulation mechanism of marine-continental transitional shale in the Upper Permian Longtan formation, Sichuan Basin, SW China. ACS Earth Space Chem. 6(9), 2199–2214 (2022).

Zhang, X. & Li, S. A lacustrine record of the early Aptian climate change by oceanic anoxic event (OAE) 1a in the Jiaolai Basin, Eastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 203, 104537 (2020).

Li, B. B. et al. Complex pattern of environmental changes and organic matter preservation in the NE Ordos lacustrine depositional system (China) during the T-OAE (Early Jurassic). Glob. Planet Change. 221, 104045 (2023).

Peters, K. E., Walters, C. C. & Moldowan, J. M. The Biomarker Guide, Biomarkers and Isotopes in Petroleum Exploration and Earth History (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005).

Shugen, L. I. et al. Sichuan basin be a super petroliferous basin?. J. Xihua Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 39, 20–35 (2020) (in Chinese with English Abstract).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Depositional environment and organic matter accumulation of Lower Jurassic nonmarine fine-grained deposits in the Yuanba Area, Sichuan Basin, SW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 116, 104352 (2020).

Li, D. H., Li, J. Z., Zhang, B., Yang, J. J. & Wang, S. Y. Formation characteristics and resource potential of Jurassic tight oil in Sichuan Basin. Pet. Res. 2(4), 301–314 (2017).

Cao, Q. Y. Identification of microcomponents and types of kerogen under transmitted light. Pet. Explor. Dev. 6(5), 14–24 (1985).

Wang, E. Z. et al. Reservoir characteristics and oil properties of a lacustrine shale system: Early Jurassic black shale from the Sichuan Basin, SW China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 242, 105491 (2023).

Espitalié, J., Madec, M., Tissot, B., Mennig, J. J. & Leplat, P. Source rock characterization method for petroleum exploration (OTC 2935). In Offshore Technology Conference, OTC, Houston, Texas 439–444 (1977).

Huang, D. F. & Li, J. C. Quantitative evaluation of source rocks. In Continental Hydrocarbon Generation in China 175–176 (Petroleum Industry Press, Beijing, 1982) (in Chinese).

Tissot, B. & Welte, D. Petroleum Formation and Occurrence 219 699 (Springer Verlag, 1984).

Bourbonniere, R. A. & Meyers, P. A. Anthropogenic influences on hydrocarbon contents of sediments deposited in eastern Lake Ontario since 1800. Environ. Geol. 28(1), 22–28 (1996).

Lu, X. et al. Distribution and geochemical significance of rearranged hopanes in Jurassic source rocks and related oils in the center of the Sichuan Basin, China. ACS Omega 6, 13588–13600 (2021).

Li, Y. J., Feng, Y. Y., Liu, H., Zhang, L. H. & Zhao, S. X. Geological characteristics and resource potential of lacustrine shale gas in the Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 40(4), 454–460 (2013).

Peters, K. E. & Cassa, M. R. Applied source rock Geochemistry. In The Petroleum System—From Source to Trap (eds Magoon, L. B. & Dow, W. G.) 93–117 (APPG Memoir 60, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 1994).

Huang, D. F., Li, J. C. & Zhang, D. J. Kerogen types and study on effectiveness limitation and interrelation of their identification parameters. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2(3), 18–35 (1984) (in Chinese with English abstract).

Golyshev, S. I., Verkhovskaya, N. A., Burkova, V. N. & Matis, E. Y. Stable carbon isotopes in source-bed organic matter of West and East Siberia. Org. Geochem. 17(3), 277–291 (1991).

Zdravkov, A. et al. Implications for peat formation in Maritsa-West Basin, SE Bulgaria: Insights from organic petrology, palynology and biomarker assemblage. Int. J. Coal Geol. 222, 103447 (2020).

Zhang, K., Liu, R., Ding, W. J., Li, L. & Liu, Z. J. The influence of Early Cretaceous paleoclimate warming event on sedimentary environment evolution and organic matter sources in Yin’e Basin: Evidence from petrology and molecular geochemistry. Int. J. Coal Geol. 254, 130972 (2022).

Volkman, J. K. Sterols and other triterpenoids: Source specificity and evolution of biosynthetic pathways. Org. Geochem. 36, 139–159 (2005).

Volkman, J. K., Farrington, J. W. & Gagosian, R. B. Marine and terrigenous lipids in coastal sediments from the Peru upwelling region at 15°S: Sterols and triterpene alcohols. Org. Geochem. 11, 463–477 (1987).

Moldowan, J. M., Seifert, W. K. & Gallegos, E. J. Relationship between petroleum composition and depositional environment of petroleum source rocks. AAPG Bull. 69, 1255–1268 (1985).

Volkman, J. K. et al. Microalgal biomarkers: A review of recent research developments. Org. Geochem. 29(5–7), 1163–1179 (1998).

Zheng, T. Y. et al. The Shahejie Formation in the Dongpu Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China: Geochemical investigation of the origin, deposition and preservation of organic matter in a saline lacustrine environment during the Middle Eocene. Int. J. Coal Geol. 253, 103967 (2022).

Martins, L. L. et al. Organic geochemical signals of freshwater dynamics controlling salinity stratification in organic–rich shales in the lower Permian Irati Formation (Paran’a Basin, Brazil). Org. Geochem. 140, 103958 (2020).

Xia, L. et al. Coupling of paleoenvironment and biogeochemistry of deep-time alkaline lakes: A lipid biomarker perspective. Earth Sci. Rev. 213, 103499 (2021).

Baydjanova, S. & George, S. C. Depositional environment, organic matter sources, and variable 17a(H)-diahopane distribution in Early Permian samples, southern Sydney Basin, Australia. Org. Geochem. 131, 60–75 (2019).

Yang, W. W., Liu, G. D. & Feng, Y. Geochemical significance of 17a(H)-diahopane and its application in oil-source correlation of Yanchang formation in Longdong area, Ordos basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 71, 238–249 (2016).

Jin, X. et al. Origin and geochemical implication of relatively high abundance of 17α(H)-diahopane in Yabulai basin, northwest China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 99, 429–442 (2019).

Li, M. J. et al. Biomarker 17a(H)-diahopane: A geochemical tool to study the petroleum system of a Tertiary lacustrine basin, Northern South China Sea. Appl. Geochem. 24, 172–183 (2009).

Jiang, L., George, S. C. & Zhang, M. The occurrence and distribution of rearranged hopanes in crude oils from the Lishu Depression, Songliao Basin, China. Org. Geochem. 115, 205–219 (2018).

Philp, P. et al. Re-arranged hopanes and novel re-arranged tricyclic terpanes in Paleozoic rock extracts and oils in the Anadarko Basin, Oklahoma. Org. Geochem. 173, 104493 (2022).

Xiao, H. et al. Identification, distribution and geochemical significance of four rearranged hopane series in crude oil. Org. Geochem. 138, 103929 (2019).

Holba, A. G., Ellis, L. & Dzou, I. L. Extended tricyclic terpanes as age discriminators between Triassic, Early Jurassic and Middle-Late Jurassic oils. In Presented at the 20th International Meeting on Organic Geochemistry, 10–14 Sept, 2001, Nancy, France (2001).

Hao, F., Zhou, X. H., Zhu, Y. M. & Yang, Y. Y. Lacustrine source rock deposition in response to co-evolution of environments and organisms controlled by tectonic subsidence and climate, Bohai Bay Basin, China. Org. Geochem. 42, 323–339 (2011).

Yang, R. F. Sedimentary environment and hydrocarbon generation of the black shales series in the Da’anzhai Member and its terrestrial response to the Early Jurassic Oceanic Anoxic Event in the Sichuan Basin, China. Ph.D thesis, Nanjing University (2019).

Rahman, M. W., Rimmer, S. M., Rowe, H. D. & Huggett, W. W. Carbon isotope analysis of whole-coal and vitrinite from intruded coals from the Illinois Basin: No isotopic evidence for thermogenic methane generation. Chem. Geol. 453, 1–11 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Projects 42090022 and U19B6003) and open fund of State Key Laboratory of Shale oil and Gas Enrichment Mechanisms and Effective Development (Project No. 33550000-22-ZC0613-0337). We thank the constructive comments from Dr. J. A. Curiale, Dr. David Curry, and Dr. Wahid Rahman. Dr. Yuxuan Wang and an anonymous reviewer are thanked for their valuable comments and suggestions. Finally, we would like to express our sincere thanks to the editor of Scientific Reports Dr. Jan Schwarzbauer for the enthusiasm, patience, and tireless efforts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.W. wrote the original manuscript; T.G. provided the original data of this study; M.L. reviewed and modified the manuscript. All authors read the manuscript and commented on it.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, E., Guo, T. & Li, M. Paleosedimentary environmental reconstruction and mechanisms of the response to the Toarcian OAE in a lacustrine shale system. Sci Rep 14, 14082 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64290-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64290-3