Abstract

This manuscript addresses a significant research gap in the study by employing a mathematical model of photo thermoelastic wave propagation in a rotator semiconductor medium under the effect of a magnetic field and initial stress, as well as ramp-type heating. The considered model is formulated during the photothermal theory and in two-dimensional (2D) electronic-elastic deformation. The governing equations represent the interaction between the primary physical parameters throughout the process of photothermal transfer. Computational simulations are performed to determine the temperature, carrier density, displacement components, normal stress, and shear stress using the application of Lame’s potential and normal mode analysis. Numerical calculations are carried out and graphically displayed for an isotropic semiconductor like silicon (Si) material. Furthermore, comparisons are made with the previous results obtained by the others, as well as in the presence and absence of magnetic field, rotation, and initial stress. The obtained results illustrate that the rotation, initial stress, magnetic field, and ramp-type heating parameter all have significant effects. This investigation provides valuable insights into the synergistic dynamics among a magnetization constituent, semiconducture structures, and wave propagation, enabling advancements in nuclear reactors' construction, operation, electrical circuits, and solar cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Researchers have long been interested in the theory of thermoelasticity because of its numerous and significant applications in a variety of disciplines, including the nuclear and aviation industries. In the field of aviation, it has been shown that the high speeds of modern aircraft lead to aerodynamic heating. Consequently, this leads to extreme heat strains and diminishes the airframe's strength by decreasing the elastic limit. Nuclear reactors' construction and operation are impacted by the extremely high temperatures and thermal gradients they produce. Likewise, the high temperatures associated with combustion processes in modern propulsion system technology, such as jet engines and rockets, are the origin of unwanted thermal stresses. Investigation on these and related problems has produced an astounding amount of theoretical and experimental research publications that address different facets of thermal stresses in engineering structures1,2,3,4. The impact of magnetic fields on solid body deformation, both thermoelastic and elastic, is the subject of the theory of magneto-thermoelasticity.

The Lorentz force, which occurs in the equation of motion, is responsible for the interactions that exist between the electromagnetic field, temperature, stress, and strain in thermoelastic material. This interaction is important because it has many applications in geophysics, such as in plasma physics, the damping of acoustic waves in a magnetic field, electrical power engineering, optics, emission of electromagnetic radiation from nuclear devices, and the influence of the earth's magnetic field on seismic waves. Ezzat5 studied the magneto-thermoelastic plane waves with thermal relaxation time in a medium of perfect conductivity. Nayfeh and Nemat-Nasser6 discussed how plane waves propagate in a thermoelastic media when they are subjected to an electromagnetic field. Abd-Alla and Abbas7 investigated the behavior of stresses, temperature, and magnetic field in an infinitely long, transversely isotropic elastic cylinder using the Lord–Shulman (L–S) and Green–Lindsay (G–L) models. The generalized magneto-thermoelasticity equations in a perfectly conducting material were developed by Ezzat and Youssef8 using the Laplace and Fourier transforms approach. The mechanism of photothermal technology is based on two key parts: the first section discusses the principle of thermoelasticity (TE), which happens when a heat wave propagates across a flexible semiconductor material, causing elastic vibrations. Secondly, electronic distortion (ED) is obtained in the flexible semiconductor medium when photoexcited free carriers are produced directly. It has been used to measure several physical parameters of semiconductor materials, including temperature, specific heat, thermal diffusivity, and others9,10. Lotfy and Tantawi11 investigated the interaction of photothermal elastic waves in a nanocomposite non-homogeneity functionally graded semiconductor elastic material in the presence of an initial magnetic field. Within the context of the theory of two temperatures and the spherical photo-thermal transport process cavity, Mondal and Sur12 examined thermal, mixed elastic, and plasma waves within a semiconducting orthotropic infinite media. Applications for problems requiring initially stressed elastic media may be found in a number of fields, including solid mechanics, seismology, geophysics, and earthquake engineering. Many studies have investigated the effects of initial stress on a variety of issues for more details, see13,14,15. Most large bodies such as Earth, moon and other planets have an angle speed, so we need to study the spread of the plane thermoelastic waves in the center of a roundabout with thermal relaxation. Several authors16,17,18,19,20 studied the effect of rotation on elastic waves in the circles. Some new contributions in semiconductors with varies external forces was discussed in (Refs.21–27).

In this paper, we study the effect of magnetic field and initial stress on the rotating semiconductor medium with ramp-type heating subjected to certain boundary conditions. An external heat source illuminates the surface of a semiconductor material. The basic governing equations is formulated in the \(x-y\) plane and in the context of the photothermal theory. Considering the interaction between elastic, plasma, and thermal waves. The physical quantities such as temperature, carrier density, displacement distributions, and thermal stress were obtained using Lame’s potential and normal mode analysis (NMA). Moreover, the MATHIMATICA program will be used to graph and explain the results (in 2D and 3D). Comparisons are made with other papers in the same direction. The results show that magnetic field, rotational velocity, initial stress, and ramp-type heating parameters have significant influence on field variables. The system is extremely valuable for scientists and engineers developing high-quality semiconductor materials that are used in many modern businesses and have various applications in electrical circuits and solar cells (photovoltaics).

Basic equations and formulation

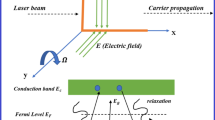

We consider a homogeneous, isotropic, initially stressed, thermoelastic material with ramp-type heating in the \(x-y\) plane (see Fig. 1). Assume that, the medium rotates in a regular manner such that the angular velocity in this case is \(\overrightarrow{\Omega }=\Omega \overrightarrow{n}\), where \(n\) is a unit vector representing the rotation axis's direction. Consequently, the displacement equation of motion in a rotating frame has two additional terms, Centripetal acceleration \((\overrightarrow{\Omega }\wedge (\overrightarrow{\Omega }\wedge \overrightarrow{u}))\) caused by just time-varying motion, and Cariole's acceleration \((2\overrightarrow{\Omega }\wedge \overrightarrow{\dot{u}})\) caused by a moving reference frame, where \(\overrightarrow{u}=(u,v,0)\) is the dynamic displacement vector. Also, the semiconductor medium is exposed to an initial magnetic field \(\overrightarrow{\text{H}}=(0,{0,\text{H}}_{0})\) with an induced magnetic field \(\overrightarrow{\text{h}}=(\text{0,0},\text{h})\) in the z-direction. When the density of charge is ignored an induced electric field \(\overrightarrow{\text{E}}\) and a current density vector \(\overrightarrow{\text{J}}\) are created in the investigated medium, which fulfill linearized Maxwell's equations.

From Eq. (1), we can write

The force of Lorentz \(\overrightarrow{\text{F}}\) may be expressed as

where \({\mu }_{e}\) refers to the magnetic permeability, \({\text{F}}_{\text{x}}\) and \({\text{F}}_{\text{y}}\) are the components of Lorentz force vector \(\overrightarrow{\text{F}}\).

For two-dimensional formulation, the constitutive and governing relations that describe the overlapping between elastic-thermal-magneto-plasma waves in semiconductors according to the photothermal theory can be stated as.

The equations of motion without any body forces are:

The carrier density equation is:

The heat conduction equation is:

The stress –displacement relations are:

From Eqs. (4–7) with the help of Eqs. (8–10) change to

where, \({\omega }_{xy}=\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}-\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\right)\) is infinitesimal rotation, \(\gamma =(3\lambda +2\mu ){\alpha }_{T}\) and \({\delta }_{n}=(3\lambda +2\mu ){d}_{n}\).

The governing equations can be expressed in a more convenient form by employing the following non-dimensional variables.

Using Eq. (15) in Eqs. (11–14), we have (removing the prime for convenience)

where

\({\nabla }^{2}=\frac{{\partial }^{2}}{\partial {x}^{2}}+\frac{{\partial }^{2}}{\partial {y}^{2}}\), \({a}_{11}=\frac{\lambda +2\mu +P+{\upmu }_{\text{e}}{\text{\rm H}}_{^\circ }^{2}}{{c}_{T}^{2}}\), \({a}_{12}=\frac{\mu -\frac{\text{p}}{2}}{{c}_{T}^{2}}\), \({a}_{13}=\frac{\lambda +\mu +\frac{3\text{P}}{2}+{\upmu }_{\text{e}}{\text{\rm H}}_{^\circ }^{2}}{{c}_{T}^{2}}\), \({a}_{14}=\frac{\lambda +2\mu }{{c}_{T}^{2}}\), \({a}_{22}=\frac{\lambda +P}{\mu }\), \({a}_{21}=\frac{\lambda +2\mu +P}{\mu }\), \({a}_{23}=\frac{\lambda +2\mu }{\mu }\),\({a}_{24}=\frac{\lambda }{\mu }\), \({a}_{n}=\frac{\text{Q}0\gamma {t}^{*}}{\rho {c}_{e}(\lambda +2\mu )}\), \({a}_{m}={a}_{n}Q\).

Solution of the problem

This section presents the application of Lame's potential and normal mode methods to solve the issue with accuracy and without assuming any constraints on the field variables that are included in the governing equations. Presenting the displacement potentials \(\phi (x,y,t)\) and \(\psi (x,y,t)\) which are connected to the displacement components by the following relations:

The following normal modes can be used to investigate the physical variable solutions:

where the angular frequency, the imaginary number, and the wave number in the y-direction are denoted by the letters \(\omega , i, and b\).

Employing Eqs. (23) and (24), Eqs. (16–19) become, respectively:

where \({D}^{2}=\frac{{d}^{2}}{{dx}^{2}}\), \({\gamma }_{11}=\frac{{a}_{12}+{a}_{13}}{{a}_{11}}\), \({\gamma }_{12}=\frac{{a}_{14}}{{a}_{11}}\), \({\gamma }_{13}=\frac{\rho }{{a}_{11}}\), \({\gamma }_{14}=\frac{\rho {\Omega }^{2}}{{a}_{11}}\), \({\gamma }_{15}=\frac{{a}_{11}-{a}_{13}}{{a}_{12}}\), \({\gamma }_{16}=\frac{\rho }{{a}_{12}}\), \({\gamma }_{17}=\frac{\rho {\Omega }^{2}}{{a}_{12}}\), \({\gamma }_{18}=\frac{{a}_{16}}{{a}_{15}}\), \({\gamma }_{19}=\frac{{a}_{17}}{{a}_{15}}\), \({\gamma }_{20}=\frac{\omega }{{a}_{15}}\), \({\gamma }_{22}=\frac{{a}_{19}}{{a}_{18}}\), \({\gamma }_{23}=\frac{{a}_{10}\omega }{{a}_{18}}\), \({\gamma }_{24}=\frac{{a}_{m}}{{a}_{18}}\), \({m}_{11}={\text{b}}^{2}{\gamma }_{11}+{\gamma }_{13}{\omega }^{2}-{\gamma }_{14}\), \({m}_{22}={\text{b}}^{2}{\gamma }_{15}+{\gamma }_{16}{\omega }^{2}-{\gamma }_{17}\), \({m}_{33}={\text{b}}^{2}+{\gamma }_{18}+{\gamma }_{20}\), \({m}_{44}={\text{b}}^{2}-\frac{\omega }{{a}_{18}}\).

Eliminating \({\phi }^{*}(x)\), \({T}^{*}(x)\), and \({N}^{*}(x)\) from Eqs. (25–28) yields the following sixth order equation

The characteristic equation of Eq. (29) is

where, \({A}_{11}={m}_{11}+{m}_{33}+{m}_{44}+{\gamma }_{12}{\gamma }_{23}\), \({A}_{22}={m}_{11}{m}_{33}+{{m}_{11}m}_{44}+{m}_{33}{m}_{44}-{\gamma }_{12}{\gamma }_{23}{m}_{33}+{\text{b}}^{2}{\gamma }_{12}{\gamma }_{23}+{\gamma }_{12}{\gamma }_{19}{\gamma }_{23}+{\gamma }_{19}{\gamma }_{24}\), \({A}_{33}={-m}_{11}{m}_{33}{m}_{44}-{m}_{33}{\text{b}}^{2}{\gamma }_{12}{\gamma }_{23}+{\gamma }_{12}{\gamma }_{19}{\gamma }_{23}{\text{b}}^{2}\), \({\lambda }_{i}, i=\text{1,2},\text{3,4},\text{5,6}\) are the all roots for this equation.

The general solutions of Eqs. (25–28), bound as x → ∞, are given by:

where \({G}_{1}={m}_{11}{\gamma }_{19}{\gamma }_{24}\), \({G}_{2}=\frac{{G}_{1}}{{A}_{33}}\), \({G}_{3}=\frac{{m}_{33}{G}_{2}}{{\gamma }_{19}}\), \({G}_{4}=\frac{-{\gamma }_{12}({G}_{2}+{G}_{3})}{{m}_{11}}\), \({\beta }_{1}=\frac{{m}_{33}}{{\gamma }_{19}}\), \({\beta }_{2}=\frac{-{\gamma }_{12}({\gamma }_{19}+{m}_{33})}{{m}_{11}{\gamma }_{19}}\), \({\alpha }_{1i}=\frac{{m}_{33}-{{\lambda }_{i}}^{2}}{{\gamma }_{19}}\), \({\alpha }_{2i}=\frac{{{\gamma }_{12}(m}_{33}-{{\lambda }_{i}}^{2})+{\gamma }_{12}{\gamma }_{19}}{{\gamma }_{19}({{\lambda }_{i}}^{2}-{m}_{11})}\), \(i=\text{1,2},3\).

The displacement components may be calculated in the following manner by using Eqs. (23), (24), (33) and (34) as follows:

By using Eqs. (20–22), and (31)–(36), the stress components may be determined

Boundary conditions

The following non-dimensional boundary conditions will be considered to avoid unbounded solutions at infinity while ignoring the positive exponential. The unknown parameters \({A}_{i}\), \(i=1, 2, \text{3,4}\) will be determined in this part using the suitable conditions for our problem. Also, we assume that the free surface in our suggested model is traction-free.

-

(I)

The plasma condition (carrier density) during the photo-thermal can be presented as

$$\frac{\partial N}{\partial x}=\frac{c}{{D}_{e}}N \text{at} x=0,$$(40) -

(II)

The normal stress condition (at the free surface) is

$${\sigma }_{xx}=0 \text{at} x=0,$$(41) -

(III)

The shearing stress is traction-free, then

$${\sigma }_{xy} =0 \text{at} x=0,$$(42) -

(IV)

The thermal boundary condition according to ramp-type heating at \(x\) = 0 is as follows

$$T=\frac{{T}_{1}t}{{t}_{o}}, 0<t\le {t}_{o}.$$(43)

Applying the conditions in Eqs. (40–43) yields four equations for the constants \({A}_{1}\), \({A}_{2}\), \({A}_{3}\) and \({A}_{4}\).

where \({S}_{1}=-{\lambda }_{1}-\frac{c}{{D}_{e}}\), \({S}_{2}=-{\lambda }_{2}-\frac{c}{{D}_{e}}\), \({S}_{3}=-{\lambda }_{3}-\frac{c}{{D}_{e}}\), \({S}_{4}={a}_{21}{\alpha }_{21}{{\lambda }_{1}}^{2}-{b}^{2}{a}_{22}{\alpha }_{21}-{a}_{23}{\alpha }_{11}\), \({S}_{5}={a}_{21}{\alpha }_{22}{{\lambda }_{2}}^{2}-{b}^{2}{a}_{22}{\alpha }_{22}-{a}_{23}{\alpha }_{12}\), \({S}_{6}={a}_{21}{\alpha }_{23}{{\lambda }_{3}}^{2}-{b}^{2}{a}_{22}{\alpha }_{23}-{a}_{23}{\alpha }_{13}\), \({S}_{7}={iba}_{21}\sqrt{{m}_{22}}-{iba}_{22}\sqrt{{m}_{22}}\), \({{S}_{8}=-2ib\alpha }_{21}{\lambda }_{1}\), \({{S}_{9}=-2ib\alpha }_{22}{\lambda }_{2}\), \({{S}_{10}=-2ib\alpha }_{23}{\lambda }_{3}\), \({S}_{11}={b}^{2}+{m}_{22}\), \({R}_{m}=(\frac{c}{{D}_{e}}-1){G}_{2}\), \({R}_{n}={b}^{2}{a}_{22}{{\beta }_{2}G}_{2}+{a}_{23}{{\beta }_{1}G}_{2}\), \({R}_{o}=-{{\beta }_{1}G}_{2}\).

To calculate the constants \({A}_{1}\), \({A}_{2}\),\({A}_{3}\) and \({A}_{4}\), Cramer's method is applied as there are three non-homogeneous equation in Eqs. (44–47).

where

The following dimensionless expressions of physical quantities (\(u\), \(v\), \(N\), \(T\),\({\sigma }_{xx}\),\({\sigma }_{yy}\), \({\tau }_{xy}\)) can be derived from Eqs. (31–36) and (24)

Numerical results and discussion

To demonstrate the behavior of wave propagation of the main physical variables and the findings gained in the preceding section, we chose silicon (Si) as an example of an elastic semiconductor material. The numerical calculations for the distributions of temperature, carrier density, stress, and displacement components were carried out using MATHIMATICA software to represent the outcomes graphically. The physical constants of the silicon element are listed below28,29.

ρ = 2330 kg/m3, λ = 3.64 × 1010 N/m2, µ = 5.46 × 1010 N/m2, \({T}_{^\circ }\) = 300 K, K = 150 W/m k, \({c}_{e}\) = 695 m2/K, \({E}_{g}=1.11\) eV, \({D}_{e}=2.5\times 1{0}^{-3}{\text{m}}^{2}{\text{s}}^{-1},{\alpha }_{t}=4.14 \times {10}^{-6}{\text{k}}^{-1},c=2{\text{ms}}^{-1},t=0.1\text{s},\) \({d}_{n}=9\times 1{0}^{-31},\) \(\tau =5\times 1{0}^{-5}\) s.

2D representation

Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 show numerical and graphical calculations of the temperature, carrier density, thermal stress, and displacement components with distance. Note that the computations have been done at different values in the presence of magnetic field, rotation, and initial stress as well as in the absence of them. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate how the absolute of the temperature and carrier density change with distance based on several factors, including magnetic field, rotation, initial stress, and the ramp-type heating parameter. The magnitude of temperature and carrier density under the effect of both the magnetic field \(H_{0}\) and rotation \(\Omega\) on the temperature and the carrier density fluctuates. It increases in the period [0, 0.008] and decreases in the period [0.008, 0.01]. The exact opposite happens with the initial stress \(P\). It decreases in the period [0, 0.008] and increases in the period from [0.008, 0.01]. But in proportion for the ramp-type heating parameter \({\text{t}}_{\text{o}}\), it decreases over the entire period [0, 0.01]. The research findings indicate that waves exhibit depth-dependent characteristics, which are crucial in understanding their behavior. The study also highlights the correlation between magnetic fields, rotation, and wave propagation, as illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3, while it illustrates the intriguing dynamics of temperature and carrier density change in relation to distance within the examined semiconducture thermoelastic model. Initially, there is a robust ascent in the temperature distribution and carrier density as distance expands, eventually giving way to a gradual descent. This phenomenon demonstrates the ingoing interaction between the propagating wave and the semiconducting medium. The intriguing behavior seen may be due to the intricate characteristics of temperature and other physical quantities, which are well-known for their ability to induce simultaneous harmonic vibrations31,32.

Figure 4 displays the effects of magnetic field \(H_{0}\), rotation \(\Omega\), initial stress \(P\), and the ramp type heating parameter \({\text{t}}_{\text{o}}\) on the variation of the absolute value for the displacement component against the axial distance \(x\). From this category, it is clear that in the interval [0, 0.004], the amplitude of displacement under the effect of both the magnetic field \(H_{0}\) and initial stress \(P\) decreases and increases in the interval [0.004, 0.01]. The importance of these discoveries lies in their implications for the behavior of waves in semiconducture magnetization-thermo-elastic mediums. The authors demonstrate that the selection of a parameter value significantly impacts the extent and behavior of particle mobility on the semiconducure medium. As well, it increases in the interval [0, 0.004] and decreases in the interval [0.004, 0.01] under the influence of rotation \(\Omega\). But because of the ramp-type heating parameter \({\text{t}}_{\text{o}}\), the displacement distribution values decrease dramatically as horizontal distance rises. This behavior seamlessly aligns with the expected characteristics of displacement components within semiconducture mediums, Hobiny et al.32, wherein higher harmonic vibrations invariably correlate with more rapid wave propagation. It is observed that the displacement component u exhibits oscillatory behavior in the region 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.1 and is greatly influenced by \(H_{0}\), \(\Omega\), \(P\), and \({\text{t}}_{\text{o}}\). Due to the photothermal effect, the semiconductor thermoelastic waves (described by the displacement component u) on the surface are generated with a positive amplitude, which starts reducing when moving away from the source. After that, the semiconductor thermoelastic waves start showing a periodic nature. The effects of magnetic field \(H_{0}\), rotation \(\Omega\), initial stress \(P\), and the ramp type heating parameter \({\text{t}}_{\text{o}}\) on the variation of the absolute value for the normal stress distribution with respect to distance \(x\) are shown in Fig. 5. The amplitude of normal stress under the rotational and magnetic field impacts increases in the range \(0\le x\le 0.01\). Also, the normal stress decreases by increasing the values of the initial stress and the ramp-type heating parameter in the range \(0\le x\le 0.01\). Moreover, as the distance increases, there is a reduction in the amplitude of normal stress. In the starting distance values, the impact of initial stress on normal stress is distinctly prominent. The amplitude of normal stress is seen to have a lower magnitude in the scenario where there is initial stress than in the absence of it. This impact also dims with the increase in distance. In the last figure, Fig. 6 explains the relationship between the change of the absolute value for the shear stress distribution versus the distance \(x\) and the magnetic field \(H_{0}\), rotation \(\Omega\), initial stress \(P\), and the ramp type heating parameter \({\text{t}}_{\text{o}}\). The shear stress distributions start from positive values and decrease smoothly nearing the surface in the first horizontal range \(0\le x\le 0.01\) until they arrive the minimum value for all four cases due to the effect of magnetic field, initial stress, and ramp-type heating parameter. On the other hand, the numerical calculations begin to increase sharply until they reach maximum values under the rotational effect in the range \(0\le x\le 0.01\). After this discussion, we can observe from all the figures that the impact of ramp- type heating parameter on all physical distributions has a great influence on the wave propagations. In addition, the mechanical stresses satisfy the conditions that are applied to the surface. Therefore, their effects must be considered when employing them in technical and practical applications. However, if the magnetic field increases, there is a clear trend of decreasing magnitude in the shear stress. This highlights the impactful relationship between the magnetic field and the resulting amplitude of shear stress. This behavior harmoniously aligns with the anticipated traits of normal stress and shear stress within the semiconductor medium described by Ailawalia30. In this context, higher harmonic vibrations consistently correspond to swifter wave propagation.

3D representation

Finally, in the 3D representation, Figs. 7, 8, 9, and 10 showcase 3D curves that illustrate the relationship between the physical quantities being studied and both components of distance within the context of the photothermal theory. These quantities are plotted against the horizontal distance \(x\) and the vertical distance \(z\). The categories explore the impact of the magnetic field \({H}_{^\circ }\), rotation \(\Omega\), initial stress \(P\), and the ramp type heating parameter \({\text{t}}_{\text{o}}\) on photo-excited processes. It is observed that the magnitude values of the physical fields vary as the \(x\) and \(z\) axes change. It can be seen that the behaviour of these quantities is the same as the behaviour of wave propagation in 2D. The obtained curves demonstrate a strong dependence on the vertical distance, showing that all the physical quantities are involved in wave propagation. This highlights the dynamic nature of these quantities as they propagate through the medium.

Particular cases and comparisons

Neglecting the magnetic field, rotation, and initial stress

Neglecting the magnetic field, rotation, and initial stress effects (i.e., \(H_{0}\) = \(\Omega\) = \(P\) = 0) in Eqs. (11) and (12), the expressions for temperature, carrier density, displacements, and thermal stress distribution reduce to that in the generalized photo thermoelastic medium with internal heat source, leading to findings similar to those found by Praveen30 and Abbas31,32, as a particular case in this work.

The presence of magnetic field and rotation

When the magnetic field and rotation are present in the governing equations during the microtemperature process, this implies the results presented by Lotfy33, as a special case in this work.

Neglecting the magnetic field, and initial stress

Neglecting the magnetic field and initial stress effects (i.e., \({H}_{0}=P=0\)) in Eqs. (11) and (12), in the specific scenario considered in this study, the formulas for temperature, carrier density, displacements, and thermal stress distribution decrease to those in the generalized photothermal medium with internal heat source, yielding results like this reported by Abd-Alla34.

Conclusion

In the current paper, a two-dimensional problem on wave propagation in a rotating and isotropic thermoelastic medium is presented in the context of the photothermal theory and under the effects of magnetic field and initial stress subjected to ramp-type heating. The governing equations describe the interaction of thermal, plasma, mechanical, and elastic waves during elastic and electronic deformation of a semiconductor material. The formulas for the temperature field, carrier density, displacement components, and stress components were computed numerically using the normal mode technique and displayed graphically (in 2D and 3D). The analytical and graphical results of this study indicate that:

-

The model appears more general as it may be used to derive specific examples for additional thermoelastic situations.

-

It is noticed from the behavior of wave propagation that, there is a clear influence of magnetic field, rotation, initial stress, and the ramp-type heating parameter on all physical quantities.

-

The comparisons were done in two cases. The first case is when the magnetic field, rotation, and initial stress are present in the governing equations and denoted by WMF, WR, and WIN, respectively. The second is when the magnetic field, rotation, and initial stress are absent in the governing equations and denoted by WOMF, WOR, and WOIN, respectively. The impact they have on all physical distributions has a significant effect on wave propagation.

-

The magnitudes of the carrier density, displacement, temperature distribution, and stress components are all significantly impacted by the magnetic field. This suggests the physical reality that the phrase denoting positive forces that tend to accelerate metal particles also applies to the influence of a magnetic field.

-

The initial stress has an oscillatory behavior on the temperature, carrier density, and displacement variables but decreases with the stress components \({\sigma }_{xx},{\sigma }_{xy}\).

-

All of the physical expressions are decreasingly impacted by the ramp-type heating parameter.

-

The normal mode technique provides accurate solutions in the generalized thermoelastic medium without assuming any limitations on the real physical quantities that are found in the problem's governing equations.

-

The physical variables satisfy all the boundary conditions under investigation.

-

This research will help scientists studying thermoelasticity and using rotational motion, which is important in domains such as engineering, physics, robotics, planetary motion, subatomic particle behavior, and machine dynamics.

-

Numerical results indicate that, besides mechanical conditions, factors such as magnetic field and rotation significantly affect wave propagation in semiconductor medium. However, it is important to note and take into account all results drawn from a numerical model, which may not accurately reflect the properties of semiconductor materials. Therefore, further experimental verification is necessary before these results can be applied and used in the construction and operation of nuclear reactors, electrical circuits, and solar cells.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(\rho\) :

-

Material density

- \(t\) :

-

Time

- \(T\) :

-

Temperature

- \(T_{0}\) :

-

Absolute temperature

- \(u,v\) :

-

Displacement components

- \(\phi ,\psi\) :

-

Two scalar functions

- \({c}_{e}\) :

-

Specific heating at constant strain

- N :

-

Carrier density

- \(\lambda , \mu\) :

-

Lame’s constants

- \({D}_{e}\) :

-

Coefficient of carrier diffusions

- \({\alpha }_{T}\) :

-

Coefficient of the linear thermal expansion

- \(\tau\) :

-

Photo-generated carrier lifetime

- \({d}_{n}\) :

-

Coefficient of electronic deformation

- \({E}_{g}\) :

-

Energy gap of the semiconductor parameter

- \({\delta }_{n}\) :

-

Difference of deformation potential of conduction and valence band

- k:

-

Thermal conductivity

- \({\sigma }_{ij}\) :

-

Stress tensor

- \(b\) :

-

Wave number

- \(\omega\) :

-

Angular frequency

- \({\upomega }_{\text{xy}}\) :

-

Infinitesimal rotation

- Q:

-

Internal heat source function

- \(\Omega\) :

-

Rotation

- \(P\) :

-

The initial stress

References

Biot, M. A. Thermoelasticity and irreversible thermodynamics. J. Appl. Phys. 27(3), 240–253 (1956).

Lord, H. W. & Shulman, Y. A generalized dynamical theory of thermoelasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 15(5), 299–309 (1967).

Green, A. E. & Lindsay, K. A. Thermoelasticity. J. Elast. 2, 1–7 (1972).

Green, A. E. & Naghdi, P. M. Thermoelasticity without energy dissipation. J. Elast. 31, 189–208 (1993).

Ezzat, M., Othman, M. & El-Karamany, A. Electromagneto-thermoelastic plane waves with thermal relaxation time in a medium of perfect conductivity. J. Thermal Stress. 24(5), 411–432 (2001).

Nayfeh, A. & Nemat-Nasser, S. Electromagneto-thermoelastic plane waves in solids with thermal relaxation. J. Appl. Mech. 39(1), 108–113 (1972).

Abd-Alla, A. M. & Abbas, I. A. A problem of generalized magnetothermo-elasticity for an infinitely long, perfectly conducting cylinder. J. Therm. Stress. 25(11), 1009–1025 (2002).

Ezzat, M. A. & Youssef, H. M. Generalized magneto-thermoelasticity in a perfectly conducting medium. Int. J. Solids Struct. 42, 6319–6334 (2005).

Lotfy, Kh. & Gabr, M. Response of a semiconducting infinite medium under two temperature theory with photo-thermal excitation due to laser pulses. Opt. Laser Tech. 97, 198–208 (2017).

Lotfy, Kh. Analytical solutions of photo-thermal-elastic waves in a semiconductor material due to pulse heat flux with thermal memory. Silicon 12, 263–273 (2019).

Lotfy, K. & Tantawi, R. S. Photo-thermal-elastic interaction in a functionally graded material (FGM) and magnetic field. Silicon 12, 295–303 (2020).

Mondal, S. & Sur, A. Photo-thermo-elastic wave propagation in an orthotropic semiconductor with a spherical cavity and memory responses. Waves Ran. Comp. Med. 31(6), 1835–1858 (2020).

Singh, P., Chattopadhyay, A. & Singh, A. K. Rayleigh-type wave propagation in incompressible visco-elastic media under initial stress. Appl. Math. Mech. -Engl. Ed. 39, 317–334 (2017).

Atwa, S. Y. Generalized magneto-thermoelasticity with two temperature and initial stress under Green-Naghdi theory. Appl. Math. Mod. 38, 5217–5230 (2014).

Othman, M. I. A. Effect of initial stress and gravity field on micropolar thermoelastic solid with micro temperatures. J. Theo. Appl. Mech. 35(3), 847–857 (2016).

Sinha, M. & Bera, R. K. Eigenvalue approach to study the effect of rotation and relaxation time in generalized thermoelasticity. Comp. Math. Appl. 46, 783–792 (2003).

Othman, M. I. A. & Singh, B. The effect of rotation on generalized micropolar thermoelasticity for a half-space under five theories. Int. J. Solid Struct. 44(9), 2748–2762 (2007).

D. Sheoran, R. Kumar, S. Kumar (2021) Wave propagation in an initially stressed rotating thermodiffusive medium with two-temperature and micro-concentrations. Int. J. Num. Meth. Heat Fluid Flow. 31(4), 1245–1267.

Alexandrov, S., Chung, K. & Jeong, W. Stress and strain fields in rotating elastic/plastic annular disks of pressure-dependent material. Mech. Based Design Struct. Mach. 46(3), 318–332 (2018).

Othman, M. I. A. & Hilal, M. I. M. Rotation and gravitational field effect on two-temperature thermoelastic material with voids and temperature dependent properties. J. Mech. Sci. 29, 3739–3746 (2015).

Bayones, F. S., Abd-Alla, A. M., Abo-Dahab, S. M., Ahmed, S. M. & Rashid, M. M. Effect of a magnetic field and initial stress on the P- waves in a photothermal semiconducting medium with an internal heat source. Mech. Based Des. Struct. 51(3), 1501–1520 (2023).

Bayones, F. S., Kilany, A. A., Abouelregal, Ahmed E. & Abo-Dahab, S. M. A rotational gravitational stressed and voids effect on an electromagnetic photothermal semiconductor medium under three models of thermoelasticity. Mech. Based Des. Struct. 51(2), 1115–1141 (2023).

Abo-Dahab, S. M. P-waves reflection in a semiconducting photothermal diffusion medium with initial stress and magnetic field. Mech. Based Des. Struct. 50(9), 3224–3244 (2022).

Khalil, E. M. Abo-Dahab, S. M. & Kilany, A. A. Electromagnetic field and initial stress on a photothermal semiconducting voids medium under thermoelasticity theories. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 44(9), 7778–7798 (2021).

Kilany, A. A., Abo-Dahab, S. M., Abd-Alla A. M. & Abd-alla, Aboelnour N. Photothermal and void effect of a semiconductor rotational medium based on Lord–Shulman theory. Mech. Based Des. Struct. 50(7), 2555–2568 (2020).

Lotfy, Kh., Abo-Dahab, S. M., Tantawy, R. & Anwar, N. Thermomechanical response model on a reflection photothermal diffusion waves (RPTD) for semiconductor medium. Silicon 12(1), 199–209 (2020).

Abo-Dahab, S. M. & Lotfy, Kh. Two-temperature plane strain problem in a semiconducting medium under photothermal theory. Wave. Random Complex Media. 27(1), 67–91 (2017).

Lotfy, Kh. A photothermal excitation for a semiconductor medium due to pulse heat flux and volumetric source of heat with thermal memory. Waves Ran. Com. Media 31(6), 1303–1321 (2019).

Lotfy, Kh. Photothermal waves for two temperature with a semiconducting medium under using a dual-phase-lag model and hydrostatic initial stress. Waves Ran. Com. Media 27(3), 482–501 (2017).

Ailawalia, P. & Kumar, A. Ramp type heating in a semiconductor medium under photothermal theory. Silicon 12, 347–356 (2020).

Alzahrani, F. S. & Abbas, I. A. Analysis of photo-thermo-elastic response in a semiconductor media due to moving heat source. Phys. Mesomech. 23, 85–91 (2019).

Hobinya, A. D., Alzahrania, F. S. & Abbas, I. A. A study on photo-thermo-elastic wave in a semi-conductor material caused by ramp-type heating. Alex. Eng. J. 60(2), 2033–2040 (2021).

Lotfy, Kh., El-Bary, A. A. & El-Sharif, A. H. Ramp-type heating microtemperature for a rotator semiconducting material during photo-excited processes with magnetic field. Results Phys. 19, 103338 (2020).

Abd-Alla, A. M., Abo-Dahab, S. M., Salah, D. M. & Abdelhafez, M. A. Effect of rotation in a semiconductor medium under photothermal theory with ramp type heating. Sohag J. Sci. 9(3), 325–333 (2024).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.M.S. established the research point and solution method. A.M.A. solved the research problem. S.M.A.-D. designed the MATLAB code to solve the problem numerically and represent it graphically. F.M.A. was the one who explained the results and found the physical meaning of them. M.A.A. wrote the conclusion of the paper and wrote the paper as a Word file. All authors revised the final version and make the revising version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salah, D.M., Abd-Alla, A.M., Abo-Dahab, S.M. et al. Magnetic field and initial stress on a rotating photothermal semiconductor medium with ramp type heating and internal heat source. Sci Rep 14, 16456 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64485-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64485-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative thermoelastic analysis of semiconductors with an external heat source under three theories

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Photothermal interactions in micropolar generalized thermoelastic medium subjected to electromagnetic field

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Stochastic analysis and Monte Carlo simulation of magneto–opto–acoustic wave propagation in nonlocal semiconductor excitation

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Influence of nonlocal on a rotating thermoelastic medium with diffusion and double porosity

Scientific Reports (2025)