Abstract

Data regarding the association of sarcopenia with hospitalization has led to inconclusive results in patients undergoing dialysis. The main goal of this research was to investigate the association between sarcopenia and hospitalization in Chinese individuals on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). Eligible patients on CAPD were prospectively included, and followed up for 48 weeks in our PD center. Sarcopenia was identified utilizing the criteria set by the Asian Working Group on Sarcopenia in 2019 (AWGS 2019). Participants were categorized into sarcopenia (non-severe sarcopenia + severe sarcopenia) and non-sarcopenia groups. The primary outcome was all-cause hospitalization during the 48-week follow-up period. Association of sarcopenia with all-cause hospitalization was examined by employing multivariate logistic regression models. The risk of cumulative incidence of hospitalization in the 48-week follow-up was estimated using relative risk (RR and 95% CI). The cumulative hospitalization time and frequency at the end of 48-week follow-up were described as categorical variables, and compared by χ2 test or fisher's exact test as appropriate. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were also conducted to examine whether the potential association between sarcopenia and hospitalization was modified. A total of 220 patients on CAPD (5 of whom were lost in follow-up) were included. Prevalences of total sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia were 54.1% (119/220) and 28.2% (62/220) according to AWGS 2019, respectively. A total of 113 (51.4%) participants were hospitalized during the 48-week follow-up period, of which, the sarcopenia group was 65.5% (78/119) and the non-sarcopenia group was 34.7% (35/101), with an estimated RR of 1.90 (95%CI 1.43–2.52). The cumulative hospitalization time and frequency between sarcopenia and non-sarcopenia groups were significantly different (both P < 0.001). Participants with sarcopenia (OR = 3.21, 95%CI 1.75–5.87, P < 0.001), non-severe sarcopenia (OR = 2.84, 95%CI 1.39–5.82, P = 0.004), and severe sarcopenia (OR = 3.66, 95%CI 1.68–8.00, P = 0.001) demonstrated a significant association with all-cause hospitalization compared to individuals in non-sarcopenia group in the 48-week follow-up. Moreover, participants in subgroups (male or female; < 60 or ≥ 60 years) diagnosed with sarcopenia, as per AWGS 2019, were at considerably high risk for hospitalization compared to those with non-sarcopenia. In sensitivity analyses, excluding participants lost in the follow-up, the relationships between sarcopenia and hospitalization (sarcopenia vs. non-sarcopenia; severe sarcopenia/non-severe sarcopenia vs. non-sarcopenia) were consistent. This research involving Chinese patients on CAPD demonstrated a significant association between sarcopenia and incident hospitalization, thereby emphasizing the importance of monitoring sarcopenia health in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sarcopenia, a disorder defined as having a reduction in skeletal muscle mass with declining muscle strength and function, is a frequent complication in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), especially in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients undergoing renal replacement therapy1,2. Previous studies have reported prevalences of sarcopenia in chronic dialysis patients (25.6% and 28.5%)3,4.

At present, the mechanisms of sarcopenia in dialysis patients have not been completely illustrated, but some mechanisms already explored include: a) chronic low-grade inflammation: the decline of renal function results in the occurrence of inflammatory reactions and a reduced capacity to excrete inflammatory factors, which increases the degradation and decreases the synthesis of muscle protein, resulting in muscle atrophy5,6,7; b) changes in hormone levels: an imbalance of hormone levels and their interaction with the corresponding hormone receptor cause decreased protein synthesis and increased protein decomposition, eventually leading to the emergence of sarcopenia8,9,10,11,12; c) changes in living status: reductions in appetite due to metabolic waste accumulation and some prescribed drugs, dietary restrictions, and the imbalance of appetite-regulating hormones may all lead to insufficient protein intake13. Meanwhile, restricted activity during and fatigue after dialysis shortens the time taken for physical activity, which impairs muscle function; d) protein loss during dialysis: peritoneal dialysis (PD) procedure promotes protein loss from dialysate, stimulates protein degradation and reduce protein synthesis also leading to loss of muscle mass12,14.

Sarcopenia and its related traits (i.e. low muscle strength, low muscle mass, and low physical performance) have been strongly associated with a wide range of adverse clinical outcomes including mortality, cardiovascular events and poor quality of life in CKD/ESRD populations3,4,15,16,17,18. Despite studies using different definitions of sarcopenia which may affect the overall prevalence in these populations, the adverse outcomes are generally consistent.

However, there is limited knowledge regarding the effects of sarcopenia on hospitalization among dialysis patients. There were two previous studies that followed hemodialysis (HD) patients to assess the impact of sarcopenia on hospitalization outcomes, however the data has led to inconclusive results19,20. Thus, for the hospitalization, more evidence is needed to conclude associations with sarcopenia in dialysis patients.

To our knowledge, there are no studies that have investigated the correlation of sarcopenia with hospitalization based on longitudinal studies among Chinese PD patients. Therefore, in this study, by utilizing the criteria of Asian Working Group on Sarcopenia in 2019 (AWGS 2019) for sarcopenia diagnoses21, we conducted a prospective cohort study to longitudinally examined the associations of sarcopenia and hospitalization over a 48-week follow-up among patients on continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD).

Materials and methods

Study design

This prospective cohort study was conducted at a PD center of Ningbo NO.2 Hospital, the tertiary care center in the Ningbo region, Zhejiang Province, China. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their families, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningbo NO.2 Hospital (YJ-NBEY-KY-2021–155-01). All research was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Visits were paid at weeks 0(baseline), 12, 24, 36 and 48. Baseline visit was immediately paid after patients enrolled. During the baseline visit, demographic and clinical characteristics such as age, sex, height, weight, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, osteoporosis, cirrhosis, et al.), concomitant medications (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI)/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB)/angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), erythropoietin (EPO)/hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (HIF-PHI), phosphate binders/active vitamin D analogues/calcimimetics, diuretics, insulin/oral anti-diabetic agents, antiplatelet agents, statins, et al.), the history of hospitalization in the past year, and Kt/V(urea) were collected. Furthermore, laboratory parameters such as serum albumin, hemoglobin, serum potassium, calcium, phosphate, and intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), together with indicators of muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance were also measured. During the period of visits, number and length of hospitalizations for each participant were collected prospectively, and updated and stored by electronic medical records. The causes of hospitalization were also recorded. At the end of the visit, hospitalization data were summarized.

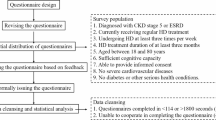

Participants

Patients with ESRD who performed CAPD were recruited from January to June 2022. Individuals aged ≥ 18 years and undergoing CAPD for at least 3 months were included. Patients were excluded if they were in a catabolic state (including malignancy or recurrent peritonitis); or unable to complete bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) (such as with pacemakers or implantable defibrillators), handgrip strength (HGS) measurement, or physical performance tests; or concurrent with critical illness, including advanced heart disease or severe lung disease; or not suitable for the clinical trial.

Outcome and sample size

The primary outcome was all-cause hospitalization during the 48-week follow-up period. Due to the inconclusive data of previous researches, and the exploratory nature of our study, sample size calculations were not done prior to data collection. The number of eligible individuals screened in our PD center determined the sample size.

Assessment of sarcopenia

Muscle mass

Muscle mass was assessed using a segmental multifrequency BIA device (InBody720, Biospace, Korea). The InBody720 uses eight tactile electrodes (at the hands and feet) to detect segmental body composition, including body water, fat, muscle, and mineral content. Patients were asked to empty the bladder and peritoneal dialysate, remove their shoes and socks, wear only their underwear, and stand over the electrodes on the machine for 3–5 min. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM) were then obtained by adding skeletal muscle mass (SMM) in all 4 limbs. To adjust for body size, we calculated the appendicular skeletal muscle mass index (ASMI) by ASM indexed to height squared (m2). The cut-off value for defining low muscle mass (LMM) was based on the ASMI, with < 7.0 kg/m2 in men and < 5.7 kg/m2 in women according to AWGS 2019.

Handgrip strength

A handgrip dynamometer (EH101, Camry, Guangdong Xiangshan Weighing Apparatus Group Ltd., Zhongshan, China) was used to measure grip strength. Patients were instructed to hold the dynamometer in the dominant hand in the standing position and use maximum isometric effort for about 5 s. Two measurements were made and we used the maximal value for analysis. As per AWGS 2019, the cut-off points for low muscle strength (LMS) were defined as grip strength < 28.0 kg for men and < 18.0 kg for women.

6-Meter walk test and 5-time chair stand test

The patients were asked to empty the peritoneal dialysate before the tests. During the 6-m walk test, patients were instructed to walk with their usual speed for 6 m on a flat and straight path. A stopwatch was used and the timing began with a verbal start command. Patients were instructed to maintain their speed without deceleration at the end of the walking course. The time (s) required to cover the distance was recorded. During the 5-time chair stand test, the participants stood up and sat down five times with their arms folded in front of their chest as quickly as possible on a firm chair. The time (s) required to complete five cycles was measured. AWGS 2019 recommends defining low physical performance (LPP) based on either 6-m walk test > 6.0 s or 5-time chair stand test > 12.0 s.

Sarcopenia definition

Sarcopenia was the exposure of interest. As per AWGS 2019, Sarcopenia was defined as low muscle mass plus low muscle strength or low physical performance. Subjects with low muscle mass, low muscle strength, and low physical performance were considered severe sarcopenia.

Statistical analysis

The data set with completed baseline visit (220 participants) was utilized for the primary analyses. 2.3% (5/220) paticipants were lost in follow-up with incomplete information regarding hospitalization. The missing data were not imputed due to its small proportion, and we instead used this data set (215 participants) for sensitivity analysis.

Baseline characteristics were summarized and compared according to sarcopenia status (sarcopenia and non-sarcopenia). Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and histogram. Variables with normal distributions were expressed as mean and standard deviation, and compared using Student’s independent t-test; variables that were not normally distributed were expressed as median (interquartile range), and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (n) with percentage (%), and compared using the χ2 or fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

The relative risk of cumulative incidence of hospitalization between sarcopenia and non-sarcopenia groups at the end of 48-week follow-up was estimated using RR and 95% CI. The cumulative time and frequency of hospitalization at the end of 48-week follow-up were described as categorical variables by sarcopenia status, and compared by χ2 test or fisher's exact test as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the associations between sarcopenia and hospitalization. ORs and their 95% CIs (sarcopenia vs. non-sarcopenia; severe sarcopenia/non-severe sarcopenia vs. non-sarcopenia) were calculated. To obtain more reliable findings, potential confounders including sex, age, comorbidities, concomitant medications, and the history of hospitalization in the past year were controlled. Three models were estimated: model 1 unadjusted; model 2 adjusted for age and sex; model 3 adjusted for model 2 plus comorbidities, concomitant medications and the history of hospitalization in the past year. The comorbidities and concomitant medications were described as categorical variables in models.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine whether the potential association of sarcopenia and hospitalization was modified by age (< 60 years vs. ≥ 60 years), and sex (male vs. female). Considering the limited number, only age (as continuous variable) and the history of hospitalization in the past year were controlled in subgroup analyses. To test the robustness of the estimation and account for losses to follow-up, a sensitivity analysis was performed using the data set (215 participants) excluding the lost in follow-up. Considering the potential for type I error due to the issue of multiplicity, findings of secondary analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

Differences were considered statistically significant at a two-tailed P value < 0.05. IBM SPSS statistics version 19.0 for Windows was used to analyze the data. Forest plots were performed using MedCalc version 20.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningbo NO.2 Hospital , Ningbo, China (YJ-NBEY-KY-2021–155-01), and informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their families.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

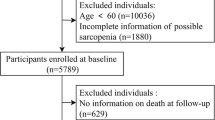

Of the 268 CAPD patients screened for inclusion in this study, 220 patients were enrolled, 5 of whom were lost in the follow-up (Fig. 1). According to the sarcopenia status, the baseline characteristics of participants (n = 220) are listed in Table 1. A total of 118 (53.6%) participants were men; the median age was 58 (46, 66) years old, and was significantly higher in the sarcopenia group (P < 0.001; Table 1). Among these 220 participants, the prevalence of sarcopenia was 54.1% (119/220), of which, non-severe sarcopenia was 25.9% (57/220) and severe sarcopenia was 28.2% (62/220). Meanwhile, the characteristics of ASM, ASMI, HGS, 6-m walk test and 5-time chair stand test were presented according to the sarcopenia status in Table 2.

Sarcopenia and hospitalization

During the 48-week follow-up period, 113 (51.4%) patients were hospitalized. The most common causes of hospitalization were fatigue(58.0%), cardiovascular events (22.0%) and PD-associated peritonitis (9.6%). Table 3 showed the cumulative incidence, time and frequency of hospitalization according to baseline sarcopenia status during the 48-week follow-up period. Compared to non-sarcopenia group, the cumulative incidence of hospitalization in sarcopenia group was significantly higher (65.5% vs. 34.7%, P < 0.001) (Table 3), with an estimated RR of 1.90 (95%CI 1.43–2.52). Meanwhile, the cumulative hospitalization time and frequency between sarcopenia and non-sarcopenia groups were significantly different (both P < 0.001, Table 3).

Based on the status of sarcopenia, logistic models were carried out to calculate the ORs and their corresponding 95%CIs for the effects of sarcopenia. In the crude model (model 1), the participants who had sarcopenia (sarcopenia vs. non-sarcopenia; severe sarcopenia/non-severe sarcopenia vs. non-sarcopenia) showed higher odds of having hospitalization (Table 4) . After adjustment for sex and age in model 2, all associations were still significant (Table 4). After further adjustment for comorbidities, concomitant medications, and the history of hospitalization in the past year in model 3, sarcopenia (OR = 3.21, 95%CI 1.75–5.87, P < 0.001), non-severe sarcopenia (OR = 2.84, 95%CI 1.39–5.82, P = 0.004) and severe sarcopenia (OR = 3.66, 95%CI 1.68–8.00, P = 0.001) were still associated with increased odds of hospitalization during the 48-week follow-up period (Table 4; Fig. 2A).

Forest plots of the associations between sarcopenia and all-cause hospitalization in (A) primary analyses, (B) sensitivity analyses, and (C) subgroup analyses. Model 1, unadjusted; Model 2, adjusted for age and sex; Model 3, adjusted for age, sex, comorbidities, concomitant medications, and the history of hospitalization in the past year.

Subgroup analyses

According to the subgroup analyses using the logistic models adjusted for age and the history of hospitalization in the past year, associations were still statistically significant. As shown in Table 5 and Fig. 2C, participants in subgroup (male or female; < 60 or ≥ 60 years) diagnosed with sarcopenia, as per AWGS 2019, were at considerably high risk for hospitalization compared to those with non-sarcopenia.

Model used in subgroup analyses adjusted for age and the history of hospitalization in the past year.

Sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses, excluding participants lost in the follow-up, we obtained similar results using model 1–3. All the relationships between sarcopenia (sarcopenia vs. non-sarcopenia; severe sarcopenia/non-severe sarcopenia vs. non-sarcopenia) and hospitalization were consistent with models in Table 4 (Table 6; Fig. 2B).

Discussion

Based on the findings, it was found that sarcopenia was significantly associated with higher risk of all-cause hospitalization in the 48-week follow-up. In sensitivity analyses, excluding participants lost in the follow-up, the relationships between sarcopenia and hospitalization remained unchanged. According to subgroup analyses, participants in subgroup (male or female; < 60 or ≥ 60 years) diagnosed with sarcopenia were still associated with an increased risk of hospitalization during the 48-week follow-up period. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to investigate the associations of sarcopenia and hospitalization among Chinese PD patients.

Two studies followed dialysis patients to assess the impact of sarcopenia on hospitalization outcomes. The first study included 126 chronic HD patients with 3-year follow-up. The authors reported no significant difference in the incidence of hospitalization between sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic patients without absolute reported number19. In contrast, the second study followed 170 patients on maintenance HD for 3 years. The risk of hospitalization was significantly higher in sarcopenic patients with a fully adjusted RR (adjusted for age, sex, dialysis vintage, and diabetes mellitus) of 2.07 (95%CI 1.48–2.88)20. In our study, compared to non-sarcopenia group, the cumulative incidence of hospitalization in sarcopenia group was significantly higher (65.5% vs. 34.7%, P < 0.001), with an estimated RR of 1.90 (95%CI 1.43–2.52) in PD patients. The paradoxical results may be partly explained by varied sarcopenia definitions, inconsistent inclusion criteria, and different sample sizes in these studies. Thus, for the hospitalization, more evidence is needed to conclude associations with sarcopenia in dialysis patients. Of note, muscle disuse and bed rest during hospitalization may further increase muscle and strength losses, which may persist even after hospital discharge22,23. This scenario turns CKD patients that have been previously hospitalized more prone to falls, fractures, infections, and rehospitalization24,25.

Our study showed that the most common causes of hospitalization were fatigue (58.0%), which has been increasingly recognized as an important symptom in patients with kidney failure requiring maintenance dialysis26. Fatigue affects 20%-91% of patients with CKD, and the prevalence increases with advancing CKD stages27,28,29. In sum, approximately two-thirds to three-quarters of patients with CKD experience fatigue, with as many as one in four reporting severe symptoms. Sarcopenia is one of the most concerning results of protein-energy wasting and is a strong correlate of poor physical functioning30, which may further aggravate the symptom of fatigue. A previous study evaluated 119 PD patients with the mean age of 66.8 ± 13.2 years and the mean follow-up period of 589.2 days. According to the multivariate logistic regression model, sarcopenia was significantly correlated with frailty (adjusted OR = 12.2, 95% CI 2.27–65.5) 31. Meanwhile, a prospective study of 266 consecutively recruited outpatients with CKD stages 2–5 reported that the presence of any fatigue versus none, were independently associated with a composite of death, hospitalization, or dialysis initiation32.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a highly common cause of hospitalization in patients undergoing dialysis. The relationship between sarcopenia and cardiovascular events were reported in two studies33,34 and were included in a meta-analysis. According to adjusted OR, sarcopenia was significantly associated with increased cardiovascular events in dialysis patients (adjusted OR = 3.80, 95%CI 1.79 to 8.09)3. The meta-analysis demonstrated that sarcopenia in dialysis patients was one of the most important predictors of cardiovascular events, and this was independent of study design, population, sex, continent, dialysis method, sarcopenia definition, and study quality3.

We also explored the association between sarcopenia and hospitalization in the subgroup. Although sarcopenia has been traditionally seen as a condition associated with age, however the subgroup analyses by age (< 60 years and ≥ 60 years) failed to demonstrate a difference in the association between sarcopenia and hospitalization in our study, implicating the importance of screening sarcopenia even in young PD patients. These results may be attributed to the systemic inflammatory condition and multiple comorbidities in dialysis-dependent patients, which could reduce the interaction between age and sarcopenia. Moreover, the analysis suggested that the sex had no significant effect on the correlation of sarcopenia and incidence of hospitalization. Of course, these relationships require verification in studies with large dialysis cohorts.

Some limitations of our study should be taken into account. First, because of the inherent drawbacks of observational studies, a causal relationship cannot be clearly established. Even though we have adjusted as many relevant covariates as possible in the post hoc statistics, there may be still profound residual and unmeasured confounding factors that could not be completely ruled out, which may contribute to a different outcome. Second, the follow-up duration was relatively short, spanning 48 weeks. Consequently, the long-term association between sarcopenia and hospitalization in patients undergoing dialysis could not be monitored. Conversely, dynamic changes in sarcopenia or their parameters with long-term follow-up may provide additional prognostic information. Third, the patients’ previous history of hospitalization, as a potential confounder of rehospitalization, was not deliberately considered before study, and its absence of details could have introduced some degree of bias, potentially weakening the statistical power toward the null hypothesis. Finally, only 220 cases were included in the primary analyses. Owing to relatively small sample size, there may be an increased risk of random error. The confounding factors could not be fully adjusted in regression analyses, leading to an inaccurate estamation of OR and a wider range of 95% CI (Fig. 2).

In conclusion, we demonstrated the associations of sarcopenia with higher risk of hospitalization by longitudinal analysis in PD patients, implicating that it is necessary to highlight the impact of sarcopenia among PD patients and recommend individualized lifestyle intervention that may be implemented across the health care spectrum. Because of the limitations of study, and potential for type I error, the findings should be interpreted as exploratory. More evidence is needed to draw robust conclusions and comfirm the causal relationship of sarcopenia and its traits with hospitalization in dialysis patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed in the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Carrero, J. J. et al. Screening for muscle wasting and dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 90(1), 53–66 (2016).

Stenvinkel, P. et al. Muscle wasting in end-stage renal disease promulgates premature death: established, emerging and potential novel treatment strategies. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 31(7), 1070–1077 (2016).

Wathanavasin, W. et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia and its impact on cardiovascular events and mortality among dialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 14(19), 4077 (2022).

Shu, X. et al. Diagnosis, prevalence, and mortality of sarcopenia in dialysis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 13(1), 145–158 (2022).

Stenvinkel, P. & Alvestrand, A. Inflammation in end-stage renal disease: Sources, consequences, and therapy. Semin. Dial. 15(5), 329–337 (2002).

Watanabe, H., Enoki, Y. & Maruyama, T. Sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease: factors, mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions. Biol. Pharm Bull. 42(9), 1437–1445 (2019).

Carrero, J. J. et al. Etiology of the protein-energy wasting syndrome in chronic kidney disease: a consensus statement from the International Society of Renal Nutrition and Metabolism (ISRNM). J. Ren. Nutr. 23(2), 77–90 (2013).

Frost, R. A. & Lang, C. H. Multifaceted role of insulin-like growth factors and mammalian target of rapamycin in skeletal muscle. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 41(2), 297–322 (2012).

Kir, S. et al. PTH/PTHrP receptor mediates cachexia in models of kidney failure and cancer. Cell Metab. 23(2), 315–323 (2016).

Morgan, S. A. et al. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 regulates glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 58(11), 2506–2515 (2009).

Fahal, I. H. Uraemic sarcopenia: aetiology and implications. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 29(9), 1655–1665 (2014).

Wang, X. H. & Mitch, W. E. Mechanisms of muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 10(9), 504–516 (2014).

Iorember, F. M. Malnutrition in chronic kidney disease. Front. Pediatr. 6, 161 (2018).

Rajakaruna, G., Caplin, B. & Davenport, A. Peritoneal protein clearance rather than faster transport status determines outcomes in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit. Dial Int. 35(2), 216–221 (2015).

Heitor, S. R. et al. Association between sarcopenia and clinical outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 41(5), 1131–1140 (2022).

Roshanravan, B. et al. Association between physical performance and all-cause mortality in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24(5), 822–830 (2013).

Painter, P. & Roshanravan, B. The association of physical activity and physical function with clinical outcomes in adults with chronic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 22(6), 615–623 (2013).

MacKinnon, H. J. et al. The association of physical function and physical activity with all-cause mortality and adverse clinical outcomes in nondialysis chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 9(11), 209–226 (2018).

Lin, Y. L. et al. Impact of sarcopenia and its diagnostic criteria on hospitalization and mortality in chronic hemodialysis patients: A 3-year longitudinal study. J. Formos Med. Assoc. 119(7), 1219–1229 (2020).

Lamarca, F. et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in elderly maintenance hemodialysis patients: the impact of different diagnostic criteria. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 18(7), 710–717 (2014).

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21(3), 300–307 (2020).

Van Ancum, J. M. et al. Change in muscle strength and muscle mass in older hospitalized patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 92, 34–41 (2017).

Parry, S. M. & Puthucheary, Z. A. The impact of extended bed rest on the musculoskeletal system in the critical care environment. Extrem. Physiol. Med. 4, 16 (2015).

Goto, N. A. et al. The association between chronic kidney disease, falls, and fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 31(1), 13–29 (2020).

Pérez-Sáez, M. J. et al. Increased hip fracture and mortality in chronic kidney disease individuals: The importance of competing risks. Bone. 73, 154–159 (2015).

Ju, A. et al. Establishing a core outcome measure for fatigue in patients on hemodialysis: A standardized outcomes in nephrology-hemodialysis (SONG-HD) consensus workshop report. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 72(1), 104–112 (2018).

Pagels, A. A. et al. Health-related quality of life in different stages of chronic kidney disease and at initiation of dialysis treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 10, 71 (2012).

Mujais, S. K. et al. Health-related quality of life in CKD Patients: Correlates and evolution over time. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 4(8), 1293–1301 (2009).

Senanayake, S. et al. Symptom burden in chronic kidney disease; a population based cross sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 18(1), 228 (2017).

Wilkinson, T. J. et al. Quality over quantity? Association of skeletal muscle myosteatosis and myofibrosis on physical function in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 34(8), 1344–1353 (2019).

Kamijo, Y. et al. Sarcopenia and frailty in PD: Impact on mortality, malnutrition, and inflammation. Perit. Dial. Int. 38(6), 447–454 (2018).

Gregg, L. P. et al. Fatigue in nondialysis chronic kidney disease: correlates and association with kidney outcomes. Am. J. Nephrol. 50(1), 37–47 (2019).

Kim, J. K. et al. Impact of sarcopenia on long-term mortality and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Korean J. Intern. Med. 34(3), 599–607 (2019).

Hotta, C. et al. Relation of physical function and physical activity to sarcopenia in hemodialysis patients: A preliminary study. Int. J. Cardiol. 191, 198–200 (2015).

Funding

This study was supported by Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant No.2022KY1132), and Key Medical Subjects of Joint Construction between Provinces and Cities, China (Grant No.2022-S03). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wang Lailiang, and Luo Qun contributed to the conception and design of the research. Zhu Beixia, and Xue Congping contributed to participants screening, and data collection and acquisition. Wang Lailiang contributed to statistical analyses and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. Lin Haixue, and Zhou Fangfang revised the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to approve the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Zhu, B., Xue, C. et al. A Prospective Cohort Study Evaluating Impact of Sarcopenia on Hospitalization in Patients on Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis. Sci Rep 14, 16926 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65130-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65130-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinical and novel insights into risk factors for sarcopenia in dialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2025)