Abstract

As the most abundant animal in the soil, nematodes are directly or indirectly involved in almost all soil ecological processes. Studying soil nematode population regulation is essential to understanding soil ecological processes. This study found urea combines nematode-trapping fungi to regulate the population of soil nematodes. In soil, compared with no urea, adding 0.2 mg/mL urea after applying Arthrobotrys oligospora and Dactylellina ellipsospora reduced the number of nematodes by 34.7% and 31.7%. Further, the mechanism of urea couple nematode-trapping fungi to regulate the nematode population was explored in the medium environment. The results showed that the addition of 0.2 mg/ml urea accelerated the trap formation of A. oligospora and D. ellipsosporas by 50% and 46.5%, and increased the yield of traps of A. oligospora and D. ellipsosporas by 39.5% and 40.6%, thus, the predatory efficiency of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora on nematodes was increased by 34.2% and 32.7%. In conclusion, urea regulates the predation ability of A. oligospora and D. ellipsosporas to regulate the soil nematode population. This study deepens the understanding of the regulatory pathways of the soil nematodes but also provides a potential new strategy for harmful nematode bio-control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil nematodes are widespread, abundant and highly diverse1,2. They can be divided into parasitic nematodes and free-living nematodes (saprophytic and microbivorous), which are dominant in most soil ecosystems with 33–384 species and 3.5–5 million individuals in a square meter of terrestrial soil3. They play an essential role in the material and energy cycle of the soil ecosystem due to their high abundance, diversity, and reproductive and metabolic capacity2,4,5. Underground, 60%–80% of free-living nematodes feed on soil microorganisms, directly regulating their metabolic characteristics, activity, abundance and driving their colony evolution6,7. Aboveground, soil nematodes affect plant growth and directly regulate vegetation characteristics, and the changes in vegetation characteristics react to the underground ecosystem3,8. In addition, soil nematodes also directly affect the dynamic balance of soil physical and chemical properties and thus indirectly affect the aboveground and underground soil ecosystems9. In brief, soil nematodes are one of the critical junctions for coupling the aboveground and underground parts of terrestrial ecosystems and a critical element for the dynamic balance of the ecosystem.

Studying soil nematode population (SNP) regulation is vital in understanding soil ecological processes10,11. Soil abiotic factors play a crucial role in regulating SNP, among which nitrogen (N) is considered one of the most critical factors12,13. Previous studies have shown that N addition will generally reduce the richness and diversity of soil nematodes, but nematodes with different lifestyles responded differently to N addition. For example, in the forest, grassland and farmland ecosystems, with the addition of N, the number of root herbivores, fungivores and omnivores-predators decreased, while the number of opportunistic bacterivores increased14,15,16. In addition, the response of SNP to N addition was also different in different ecosystems. For example, adding 120 kg N ha-1 yr-1 in the semi-arid grassland ecosystem suppressed SNP17. Whereas, in subtropical acidic soils of China, N addition increased SNP18. The changes in soil pH, aboveground vegetation characteristics and ammonium toxicity caused by N addition are generally considered the main pathways of SNP regulation12,19. These three SNP regulation pathways induced by N addition usually require a longer time or high level of N addition to manifest their effects. However, these three regulation pathways could not solve the controversy over the response range and even direction of SNP to N addition, and it was even more challenging to explain the changes of SNP in the short term after the addition of low N concentration20. Therefore, we speculated that there might be other unknown regulatory pathways besides the three regulatory pathways mentioned above after N addition.

Nematode-trapping fungi (NTF) are a group of fungi that can produce special mycelium structures to capture nematodes21,22. Their ability to feed on nematodes is the product of adaptive evolution in response to N deficiency in the soil habitat23,24. These fungi are widely distributed in various soil habitats and are an important balancing factor for SNP in nature25. In the course of studying these group fungi, we found that urea can change the predation characteristics of these group fungi. Therefore, we hypothesized that adding urea to the soil would drive NTF to regulate SNP. In order to verify this hypothesis, the combined regulation of urea and NTF on SNP was investigated in soil and medium environments. The results further enhance our understanding of the complexity and diversity of SNP regulation pathways and provide a potential new strategy for harmful nematode control.

Results

Effect of urea on the ability of NTF to regulate soil nematode population (SNP)

After testing, two datasets of soil nematode quantity after adding different concentrations of urea after applying A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora did not satisfy normal distribution (P = 0.012, P = 0.0003), and the latter did not satisfy variance homogeneity either (P = 0.033). After the reciprocal conversion of the original datasets, the datasets of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora are consistent with normal distribution (P = 0.143, P = 0.323) and homogeneity of variance (P = 0.503, P = 0.810). One-way ANOVA of the converted datasets showed that there are significant differences between different groups of the datasets of A. oligospora (F (6, 42) = 340, P < 0.0001) and D. ellipsospora (F (6, 42) = 352.8, P < 0.0001).

Compared with the control group, the application of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora alone decreased the number of soil nematodes by 31.8% (1371.7 vs. 935.6 nematodes, P < 0.0001) and 34.8% (1373.9 vs. 896.1 nematodes, P < 0.0001), respectively. The experimental groups showed that the addition of certain concentrations of urea could significantly reduce the number of nematodes after the application of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora: when the urea concentration was 0–0.2 mg/mL, its reducing effect on the number of nematodes gradually strengthened with increasing urea concentration. When the concentration was 0.2 mg/mL, the number of nematodes in the soil was the lowest, at an average of 610.6 (A. oligospora) and 612.4 (D. ellipsospora), which was a decrease of 34.7% (P < 0.0001) and 31.7% (P < 0.0001) compared with the 935.6 and 896.1 nematodes, respectively when no urea was added. When the urea concentration was more than 0.2 mg/mL, the effect of increasing the urea concentration on reducing the nematode population gradually weakened (Fig. 1).

The effects of different concentrations of urea on the number of soil nematodes. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 7). The lowercase and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different urea concentrations combined with Arthrobotrys oligospora and Dactylellina ellipsospora, respectively.

Trap formation rate and yield of NTF under different urea concentrations

The normal distribution and variance homogeneity test showed that the datasets of the trap formation rates and yield of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora under different urea concentrations met the normal distribution and variance homogeneity (all P values exceeded 0.05). The results of one-way ANOVA showed that there are significant differences in two datasets of trap formation rates of A. oligospora (F (5, 24) = 73.5, P < 0.0001) and D. ellipsospora (F (5, 24) = 44, P < 0.0001) under different urea concentrations. There also are significant differences in the datasets of trap yield of A. oligospora (F (5, 24) = 83.05, P < 0.0001) and D. ellipsospora (F (5, 24) = 49.85, P < 0.0001).

When the urea concentration was in the range of 0–0.2 mg/mL, with increasing urea concentration, the effect of promoting NTF to produce traps was gradually strengthened. When the urea concentration was 0.2 mg/mL, A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora required the shortest time to produce traps (they took 12.6 and 7.6 h on average, which was reduced by 50% (P < 0.0001) and 46.5% (P < 0.0001) compared with the 25.2 and 14.2 h, respectively when no urea was added (Fig. 2). In addition, at this urea concentration, A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora had the highest trap yield with an average of 662.2 and 553.8 traps, which was 39.5% (P < 0.0001) and 40.6% (P < 0.0001) higher than the 474.6 and 393.8 traps, respectively when no urea was added. When the urea concentration exceeded 0.2 mg/mL, the trap formation time and trap yield of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora gradually lengthened (Fig. 3).

Required time for trap formation of Arthrobotrys oligospora and Dactylellina ellipsospora under different urea concentrations. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5). The lowercase and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different urea concentrations combined with Arthrobotrys oligospora and Dactylellina ellipsospora, respectively.

The number of traps after 72 h of Arthrobotrys oligospora and Dactylellina ellipsospora under different urea concentrations. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5). The lowercase and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different urea concentrations combined with Arthrobotrys oligospora and Dactylellina ellipsospora, respectively.

Nematocidal ability of NTF under different urea concentrations

The test results showed that the dataset of nematode mortality under different urea concentrations is consistent with normal distribution (P = 0.284) and homogeneity of variance (P = 0.314). The one-way ANOVA result showed no significant difference in the dataset of nematode mortality under different concentrations of urea alone (F (5, 24) = 2.052, P = 0.1072). Therefore it was concluded that adding urea alone had no obvious poisoning effect on the nematodes (Fig. 4a).

Nematode mortality under different urea concentrations. (a), nematode mortality under different concentrations of urea alone; (b), Nematode mortality of Arthrobotrys oligospora and Dactylellina ellipsospora under different urea concentrations. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 5). The lowercase and uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different urea concentrations combined with Arthrobotrys oligospora and Dactylellina ellipsospora, respectively.

After the normal distribution and variance homogeneity test, the datasets of nematode mortality of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora under different urea concentrations are consistent with normal distribution (P = 0.142, P = 0.180) and homogeneity of variance (P = 0.999, P = 0.757). One-way ANOVA showed that there are significant differences in two datasets of nematode mortality of A. oligospora (F (5, 24) = 114.4, P < 0.0001) and D. ellipsospora (F (5, 24) = 85.7, P < 0.0001) under different urea concentrations.

In the experimental group, with increasing urea concentrations, nematode mortality gradually increased. When the urea concentration reached 0.2 mg/mL, the nematode mortality of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora was the highest, at an average of 85.6% and 87.2%, which was an increase of 34.2% (P < 0.0001) and 32.7% (P < 0.0001) over the 63.8% and 65.7% respectively when no urea was added. When the urea concentration exceeded 0.2 mg/mL, the promotion effect of the increase in urea concentration on the predation ability of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora was weakened (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

In this study, the number of nematodes in soil decreased by 31.8% and 34.8% after A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora were added alone (Fig. 1), emphasizing the significance of nematode-trapping fungi (NTF) in soil nematode population (SNP) regulation. After adding A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora, the density of nematodes was further changed by adding different urea concentrations. The addition of 0.2 mg/ml of urea further reduced the number of nematodes by nearly 30% (Fig. 1), indicating that different urea concentrations could regulate the regulation ability of NTF to SNP, and this pathway is an important way for SNP regulation. In the medium environment, the addition of low concentration urea (0.1–0.4 mg/mL) accelerated the formation and increased the yield of the trapping structure, then improved the ability of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora to catch nematodes. In comparison, the addition of high concentration urea (0.5 mg/mL) inhibited the formation of the trapping structure of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora (Figs. 2, 3, 4). The results confirmed that urea regulates SNP by regulating the predation ability of NTF.

The molecular mechanism by which urea regulates the insecticidal ability of NTF may be similar to the mechanism by which soil bacteria mobilize NTF to capture nematodes: certain soil bacteria release urea to the surrounding environment when they experience predation stress from nematodes, and urea enters NTF cells under urea transporters and decomposes into ammonium ions under the action of urease. As a signal factor, ammonium ions directly promote NTF to produce traps quickly to catch nematodes to protect bacterial populations from nematodes26. According to this mechanism, it can be inferred that applying a specific concentration of ammonium salt may also have a similar effect as urea. Even because ammonium salt eliminates the step of urease decomposition, it can more quickly act on NTF cells, and the effect of promoting NTF to catch nematodes may be better and faster than that of urea. Except for NTF, there are other nematophagous microorganisms in the soil to balance SNP, such as endoparasitic fungi, egg parasitic fungi and nematophagous bacteria27,28,29. Similar to NTF, the ability to feed on nematodes of these nematophagous microorganisms is thought to be the product of adaptive evolution in response to N deficiency in the soil habitat28,29,30, the change of N in soil may also change their nematocidal function, and then regulate SNP. Therefore, the combined regulatory pathways of N and these microorganisms should be emphasized in future SNP regulation studies. In addition, other soil abiotic factors besides N (such as carbon, organic matter, temperature and precipitation, etc.) also affect the species composition, richness and insecticidal characteristics of nematophagous microorganisms31,32, thus affecting the balance of SNP. Therefore, future studies should consider the combined regulatory pathways of these soil abiotic factors and nematophagous microorganisms.

Our study also provides a potential new strategy for soil harmful nematode control. Plant-parasitic nematodes are serious plant pests worldwide, causing crop-related economic losses of more than $100 billion yearly33,34. Although chemical insecticides or repellents such as Temik and Aldicarb are effective in controlling these diseases, they not only leave pesticide residues and cause ecological damage but also increase the resistance of nematodes, forming a vicious cycle35,36. Therefore, using NTF to control them is the most promising method37. However, in previous studies, most of the studied strains showed excellent nematicidal effects in pure culture, whereas their field experiment tests were unsatisfactory38,39. Improving the effectiveness of these preparations is the greatest challenge of applying NTF. In this study, the addition of a proper concentration of urea can significantly improve the predation efficiency of NTF on nematodes, whether in the culture medium or field soil environment (Figs. 2, 3, 4). In addition, as one of the most commonly used N fertilizers in agricultural production, urea has the advantages of low costs and nontoxic side effects. Therefore, adding urea after an NTF application can significantly improve the control effect of NTF on nematodes without greatly increasing control costs. The combined application of urea with NTF is an effective and feasible nematode control strategy.

Methods

Experimental materials

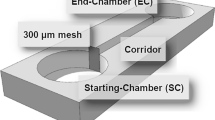

Corn meal agar (CMA) observation plate: A 20 mm diameter hole was punched in the center of the CMA plate22 with a sterile punch, and approximately 0.8 mL sterilized water agar (WA) medium22 was injected into the hole with a sterile syringe (Fig. 5).

Urea solution: An appropriate amount of urea was weighed and prepared with sterile water to form solutions with concentrations of 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 mg/mL. The solution was filtered using a filter membrane with an aperture of 0.22 μm and stored at 4 °C.

Bait nematodes: Panagrellus redivivus Goodey (a free-living soil nematode that is often used as a target organism in nematode control research)22,40,41 was provided by Germplasm Resources Center of Institute of Eastern-Himalaya Biodiversity Research. The nematodes were separated from the oatmeal medium using the Baermann funnel method42. The nematode concentration was counted by a stereo microscope and adjusted to 5 × 103/mL with sterile water.

Testing NTF strain: Arthrobotrys oligospora Fres and Dactylellina ellipsospora Preuss (Orbiliaceae, Orbiliomycetes) catch nematodes using adhesive networks and adhesive knobs, respectively22. They were identified and provided by the Germplasm Resources Center of the Institute of Eastern-Himalaya Biodiversity Research. The strain was transferred to fresh CMA plates and incubated at 27 °C for 8–15 d. Sterile water (5–6 mL) was added to the plates, the conidia of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora were eluted, and spore eluent was collected, respectively. The spore concentration was counted by cell-count boards under microscope and adjusted to 104/mL with sterile water.

Testing soil sample: The field soil containing a large number of nematodes was collected from the potato planting field in the Agronomy Practice and Teaching Base of Dali University. The large particles in the soil were sieved out, and the remaining soil was mixed. Ninety-eight soil samples (each sample weighed 2 kg) were weighed and placed into 98 flowerpots with a diameter of 38 cm. All pots were placed in a cool area, and 100 mL of sterile water was poured on them every other day to keep the soil moist. From Day 3 onwards, the nematode density of each sample was monitored every two days with the improved Baermann funnel method42, until the density of nematodes was stable three times (the 11th day). Then, follow-up experiments were carried out.

Synergistic effect of urea and NTF on soil nematode population (SNP)

The 98 pots of soil with stable nematode densities were randomly divided into 2 groups (49 pots per group) for the experiments of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora, respectively. The following experimental methods are as follows (taking the experiment of A. oligospora as an example, the experiment of D. ellipsospora is the same).

The 49 pots of soil were randomly divided into 7 groups (7 replicates per group): 1 control group and 6 experimental groups. The control group received no treatment. For the experimental groups, 30 ml spore eluent of A. oligospora was evenly added to each pot. Then, from day 18, the nematode density of each pot was monitored every other day with the improved Baermann funnel method42 until the density of nematodes was stable three times (the 28th day). 200 ml of urea solution at 6 concentrations was evenly added to each pot of the 6 experimental groups. After 18 days, one 100 g soil sample was collected evenly from each pot in the control and experimental groups (a total of 7 soil samples per treatment). The nematodes in each sample were separated and counted using the improved Baermann funnel method42. During the experiment, the pots were placed in a cool area, and 100 ml of sterile water was poured into each pot every other day to keep the soil moist.

Effect of urea on the traps formation rate and yield of NTF

Taking the experiment of A. oligospora as an example, the experiment of D. ellipsospora is the same.

Five hundred microlitres of spore eluent of A. oligospora was evenly spread onto thirty CMA observation plates and incubated at 27 °C. When the mycelium overspread the observation cell, approximately 500 nematodes (P. redivivus) were added to the observation cell of each plate. Thirty plates were randomly divided into 6 groups and marked as 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 (each group contained 5 replicates). Six concentrations of urea were added to the observation cell of the corresponding observation plates (150 μL was added to each plate). The formation of traps was observed every hour, and the earliest formation time was recorded. After 48 h, the number of traps in the observation cell was counted.

Effect of urea on the nematocidal ability of NTF

Taking the experiment of A. oligospora as an example, the experiment of D. ellipsospora is the same.

Control group: The urea and nematodes were transferred to fresh CMA observation plates according to the above methods to eliminate the toxic effect of urea on nematodes.

Experimental group: The spore eluents of A. oligospora, urea and nematodes were transferred to CMA observation plates according to the above methods. After 96 h, the dead nematodes and live nematodes in the observation cells of each plate in the control and experimental groups were counted under stereoscopic microscope, and nematode mortality was calculated.

Data management and analysis

We calculated the nematode mortality as the following formula: Nematode mortality = Number of dead nematodes/(number of dead nematodes + number of live nematodes) × 100%.

Through the above experiments, nine datasets were obtained: 1, 2) The number of soil nematodes after adding different concentrations of urea after applying A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora. 3,4) The required time for traps formation of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora under different concentrations of urea. 5, 6) The traps yields of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora under different concentrations of urea. 7, 8) The nematode mortality of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora under different concentrations of urea. 9) The nematode mortality under different concentration of urea alone. Excel (2010) was used to manage the experimental data and draw the bar charts with mean values and standard deviation (sd).

In order to clarify the effect of urea concentration on soil nematode quantity after application of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora and the effect of urea concentration on the trapping function of A. oligospora and D. ellipsospora. The differences between the control and treatment groups in each dataset were compared in pairs, respectively. The detailed methods are as follows (taking the number of soil nematodes after adding different concentrations of urea after applying A. oligospora as an example): 1) SPSS (version 20; SPSS Inc., USA) was used to perform the Shapiro–Wilk test to check the normality of data distribution. When the P value exceeds 0.05, the dataset conforms to the normal distribution and vice versa. 2) One-way ANOVA test in SPSS (version 20; SPSS Inc., USA) was used to test the variance homogeneity of the dataset. When the P value exceeds 0.05, the dataset conforms to variance homogeneity and vice versa. 3) For a dataset that satisfies both normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, the one-way ANOVA was performed using SPSS (version 20; SPSS Inc., USA) to clarify the differences in the dataset. The Tukey Honest Significance Difference test (HSD, 5% precision level) in SPSS (version 20; SPSS Inc., USA) was used further to determine the pairwise differences between treatment and control groups. If the dataset does not meet the normal distribution or homogeneity of variance, log or reciprocal conversion is performed on the dataset using the data conversion function in SPSS (version 20; SPSS Inc., USA), and steps 1 and 2 are repeated with the converted dataset. If the converted dataset meets the normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, the one-way ANOVA was performed. The HSD test at 5% precision level was used to ascertain the significance and non-significance of different treatment and control groups.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are contained within the article.

References

Wu, T., Ayres, E., Bardgett, R. D., Wall, D. H. & Garey, J. R. Molecular study of worldwide distribution and diversity of soil animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17720–17725 (2011).

Yeates, G. W. Nematodes as soil indicators: functional and biodiversity aspects. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 37, 199–210 (2003).

Neher, D. A. Ecology of plant and free-living nematodes in natural and agricultural soil. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 371–394 (2010).

Yeates, G. W. Abundance, diversity, and resilience of nematode assemblage in forest soils. Can. J. For. Res. 37, 216–225 (2007).

Zhao, J., Zhang, W., Wang, K., Song, T. & Du, H. Responses of the soil nematode community to management of hybrid napiergrass: The trade-off between positive and negative effects. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 75, 134–144 (2014).

Bonkowski, M. Protozoa and plant growth: the microbial loop in soil revisited. New Phytol. 162(3), 617–631 (2004).

Pernthaler, J. Predation on prokaryotes in the water column and its ecological implications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3(7), 537–546 (2005).

Keith, A. M. et al. Strong impacts of below ground tree inputs on soil nematode trophic composition. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 41, 1060–1065 (2009).

Buchan, D., Gebremikael, M. T., Ameloot, N., Sleutel, S. & De Neve, S. The effect of free-living nematodes on nitrogen mineralisation in undisturbed and disturbed soil cores. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 60, 142–155 (2013).

Pen-Mouratov, S., Shukurov, N. & Steinberger, Y. Soil free-living nematodes as indicators of both industrial pollution and livestock activity in Central Asia. Ecol. Indic. 10, 955–967 (2010).

Zhang, M., Liang, W. J. & Zhang, X. K. Soil nematode abundance and diversity in different forest types at Changbai Mountain China. Zool Stud. 51(5), 619–626 (2012).

Sun, X. et al. Soil nematode responses to increases in nitrogen deposition and precipitation in a temperate forest. PloS One 8(12), e82468 (2013).

Song, M. et al. Responses of soil nematodes to water and nitrogen additions in an old-field grassland. Appl. Soil Ecol. 102, 53–60 (2016).

Hu, C. & Qi, Y. Effect of compost and chemical fertilizer on soil nematode community in a Chinese maize field. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 46, 230–236 (2010).

Liang, W. et al. Nematode faunal response to long-term application of nitrogen fertilizer and organic manure in Northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41(5), 883–890 (2009).

Qi, S., Zhao, X., Zheng, H. & Lin, Q. Changes of soil biodiversity in Inner Mongolia steppe after 5 years of N and P fertilizer applications. Acta Ecol. Sin. 30, 5518–5526 (2010).

Wei, C. et al. Nitrogen addition regulates soil nematode community composition through ammonium suppression. PLoS One 7, e43384 (2012).

Jiang, C., Sun, B., Li, H. & Jiang, Y. 2013 Determinants for seasonal change of nematode community composition under long-term application of organic manure in an acid soil in subtropical China. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 55, 91–99 (2013).

Ruan, W. B. et al. The response of soil nematode community to nitrogen, water, and grazing history in the inner Mongolian steppe China. Ecosystems 15(7), 1121–1133 (2012).

Song, M. et al. Dynamics of soil nematode communities in wheat fields under different nitrogen management in Northern China Plain. Eur J Soil Biol. 71, 13–20 (2015).

Jiang, X., Xiang, M. & Liu, X. Nematode-trapping fungi. Microbiol Spectr. 5(1), 5–1 (2017).

Zhang, K. Q. & Hyde, K. D. Nematode-trapping fungi (Springer, 2014).

Su, H. et al. Trapping devices of nematode-trapping fungi: formation, evolution, and genomic perspectives. Biol Rev. 92(1), 357–368 (2017).

de Ulzurrun-, G. V. D. & Hsueh, Y. P. Predator-prey interactions of nematode-trapping fungi and nematodes: Both sides of the coin. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 102(9), 3939–3949 (2018).

Swe, A., Jeewon, R., Pointing, S. B. & Hyde, K. D. Diversity and abundance of nematode-trapping fungi from decaying litter in terrestrial, freshwater and mangrove habitats. Biodivers. Conserv. 18(6), 1695–1714 (2009).

Wang, X. et al. Bacteria can mobilize nematode-trapping fungi to kill nematodes. Nat. Commun. 5(1), 1–9 (2014).

Liu, X., Xiang, M. & Che, Y. The living strategy of nematophagous fungi. Mycoscience 50(1), 20–25 (2009).

Mendoza-de Gives, P., Braga, F. R. & Araújo, J. V. Nematophagous fungi, an extraordinary tool for controlling ruminant parasitic nematodes and other biotechnological applications. Biocontrol. Sci. Techn. 32(7), 777–793 (2022).

Niu, Q. et al. A Trojan horse mechanism of bacterial pathogenesis against nematodes. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107(38), 16631–16636 (2010).

Jansson, H. B. & Lopez-Llorca, L. V. Biology of nematophagous fungi. In Trichomycetes and Other Fungal Groups (ed. Misra, J. K.) (CRC Press, 2001).

Van den Boogert, P. H. J. F., Velvis, H., Ettema, C. H. & Bouwman, L. A. The role of organic matter in the population dynamics of the endoparasitic nematophagous fungus Drechmeria coniospora in microcosms. Nematologica 40(1–4), 249–257 (1994).

Zhang, Y. et al. Fungi–nematode interactions: Diversity, ecology, and biocontrol prospects in agriculture. J. Fungi 6(4), 206 (2020).

Akers, D., McCrystal, R. Integration of crop and soil insect management in sweetpotato vol HAL Project VG09052 Australian Sweetpotato Growers Inc. (2014).

Nicol, J. M. et al. Current nematode threats to world agriculture. In Genomics and molecular genetics of plant-nematode interactions (eds John, J. et al.) (Springer, 2011).

Fässler, H., Torgerson, P. R. & Hertzberg, H. Failure of Duddingtonia flagrans to reduce gastrointestinal nematode infections in dairy ewes. Vet. Parasitol. 147(1–2), 96–102 (2007).

Kaplan, R. M. Drug resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance: a status report. Trends Parasitol. 20(10), 477–481 (2004).

Pandey, S. K., Masurkar, P. & Singh, R. K. In-vitro screening of nematode trapping fungi against root knot nematode. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 7(6), 421–428 (2018).

Sanyal, P., Sarkar, A., Patel, N., Mandal, S. & Pal, S. Valuation of Chhattisgarh isolates of nematode trapping fungi for use as biocontrol agents against animal parasitic nematode. J. Veter. Parasitol. 23(2), 151–153 (2009).

Gomes, E. H. et al. Role of Synadenium grantii latex proteases in nematicidal activity on Meloidogyne incognita and Panagrellus redivivus. Braz. J. Biol. 79, 665–668 (2018).

Kiss, L. V., Hrács, K., Nagy, P. I. & Seres, A. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on Panagrellus redivivus (Nematoda) and Folsomia candida (Collembola) in various test media. Int. J. Environ. Res. 12(2), 233–243 (2018).

Giuma, A. Y. & Cooke, R. C. Some endozoic fungi parasitic on soil nematodes. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 59(2), 213 (1972).

Zhang, K. Q. & Mo, M. H. Flora fungorum sinicorum Arthrobotrys et genera cetera cognata (Science Press, 2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation Program of P.R. China [grant number 32360002]; and the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP) [grant number 2019QZKK0402].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. F. and H. S. collected and analyzed the data, Z. F. writ the manuscript; S. B. revised the manuscript; X. W. and Y. X. developed the research ideas and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fa, Z., Shuaiyi, H., Boonmee, S. et al. Urea regulates soil nematode population by enhancing the nematode-trapping ability of nematode-trapping fungi. Sci Rep 14, 14296 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65167-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65167-1