Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) materials have recently drawn interest in various applications due to their superior electronic properties, high specific surface area, and surface activity. However, studies on the catalytic properties of the 2D counterpart of V2O5 are scarce. In the present study, the catalytic properties of 2D V2O5 vis-à-vis bulk V2O5 for the degradation of methylene blue dye are discussed for the first time. The 2D V2O5 catalyst was synthesized using a modified chemical exfoliation technique. A massive increase in the electrochemically active surface area of 2D V2O5 by one order of magnitude greater than that of bulk V2O5 was observed in this study. Simultaneously, ~ 7 times increase in the optical absorption coefficient of 2D V2O5 significantly increases the number of photogenerated electrons involved in the catalytic performance. In addition, the surface activity of the 2D V2O5 catalyst is enhanced by generating surface oxygen vacancy defects. In the current study, we have achieved ~ 99% degradation of 16 ppm dye using the 2D V2O5 nanosheet catalysts under UV light exposure with a remarkable degradation rate constant of 2.31 min−1, which is an increase of the order of 102 from previous studies using V2O5 nanostructures and nanocomposites as catalysts. Since the enhanced photocatalytic activity emerged from the surface and optical properties of the catalyst, the current study shows great promise for the future application of 2D V2O5 in photo- and electrocatalysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) materials exhibit exotic physical, electrical, and optical properties that vary from their bulk counterparts. By altering the number of layers, the properties of 2D materials can be tailored. This distinctiveness provides opportunities for controlling the surface, optical, magnetic, and electrical properties of 2D materials for a range of applications. 2D materials are excellent choices for applications involving surface redox reactions, such as catalysis and gas sensing, because of their very high specific surface area and density of surface active states1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. For instance, graphene exhibits a high specific surface area of ~ 2600 m2/g, whereas it is ~ 8 m2/g for natural graphite9. In addition to the high surface-to-volume ratio9, the presence of edge defects in 2D structures, which are responsible for stabilizing the structure, enhances the catalytic properties. For example, graphene with zig-zag edges shows good catalytic activity10. Theoretically, edge defect states strongly increase the electronic density of states at the edges compared to the plane of 2D materials11. In addition, the presence of dislocations, vacancy defects, impurities, and functional groups can significantly increase the density of surface active states and, consequently, the catalytic activity of the materials12. The impressive mechanical stability, generally shown by 2D materials, offers high stability and durability as catalysts and catalyst supports. Additionally, materials such as graphene, which has high electrical conductivity, have been applied in electrocatalysis.

The effluent from the textile industry contains organic dye molecules that are potentially harmful to human health and the ecosystem. Textile dyes are non-biodegradable and generally highly stable under light, heat, and oxidizer exposure13. Generally, catalyst-mediated redox reactions are cost-effective methods for the degradation of textile dyes14,15,16. Semiconducting metal oxides with bandgaps in the range of visible and UV light energies, such as V2O517, SnO218, ZnO19, ZrO220, and TiO221,22, are generally used as photocatalysts. As a transition metal, V possesses multiple oxidation states23, and the vanadium oxide surface can undergo reversible redox reactions24,25. This property makes V2O5 a promising catalyst. In addition, V2O5 nanostructures with various morphologies and heterostructures of V2O5/rGO, and V2O5/graphene also show good catalytic performance26,27,28. Under ambient conditions, V2O5 crystalizes in its orthorhombic polymorph α-V2O5, a layered van der Waals crystal29. The surface of the V2O5 catalyst consists of three differently coordinated oxygen atoms: vanadyl (OI), bridge (OII), and chain (OIII) oxygen (the number in the subscript indicative of the coordination number of the oxygen atom)29. The bridging oxygen connects the double V–O chains in the crystal structure along the b-axis. The VO4 sites on the ab-plane V2O5 surface are the active surface sites for catalysis30. The supported vanadium oxide catalysts on oxide surfaces also tend to show improved catalytic performance by controlling the specific activity of VO4 sites30.

Using 2D V2O5, one can significantly reduce the defect formation energy and increase the active surface area for the catalytic reaction, consequently improving the catalytic performance. However, the catalytic properties of the 2D counterpart of V2O5 have not been reported before. The present study thoroughly examined the catalytic property of 2D V2O5 for the degradation of organic dyes. The chemically exfoliated V2O5 nanosheets were used as catalysts in the current study. The photocatalytic performance of 2D V2O5 for the degradation of methylene blue (MB) dye was investigated and compared with that of bulk V2O5.

Methods

Synthesis and characterization of 2D V2O5 nanosheets

2D V2O5 nanosheets were synthesized by a modified chemical exfoliation method by altering the concentration of bulk V2O5 in formamide29. Previous reports have shown that V2O5 intercalated with formamide molecules can provide a stable suspension of tiny flakes of V2O5 in formamide medium29,31. For the synthesis, bulk V2O5 powder (Merck, 99.99%) was dispersed in formamide (Merck, 99%) for 24 h. To separate the exfoliated nanosheets, the dispersion of formamide-intercalated V2O5 was subjected to a 1 h ultrasonic treatment at room temperature. The resultant suspension was then coated on a quartz substrate by drop casting (for the photocatalysis study), followed by heating at 100 °C to completely remove the formamide molecules. Furthermore, the exfoliated nanosheets were annealed for three hours at 250 °C under a continuous flow of O229. The substrate was replaced with SiO2/Si and high pure gold for AFM and Raman spectroscopic studies, respectively.

A multimode scanning probe microscope (INTEGRA, NT-MDT, Russia) was used to record the atomic force microscopy (AFM) topography and estimate the thickness of the exfoliated nanosheets coated on the SiO2/Si substrate. Intermittent contact mode was used for imaging. Atomic-resolution STEM images were collected using probe aberration-corrected Thermo Fisher Scientific Themis Z ultrahigh-resolution TEM at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. Oxygen vacancy defects in the sample were identified using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (SPECS Surface Nano Analysis GmbH, Germany). A monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.7 eV) was used for the XPS measurements. Ultraviolet‒visible (UV‒Vis) absorption spectroscopy (Avantes) was carried out in absorption mode to determine the band gap. UV‒Vis absorption spectra of the bulk and 2D V2O5 nanosheets were collected using a cuvette with a width of 1 cm and the same light source. Raman spectroscopy (InVia, Renishaw, UK) was carried out utilizing a 532 nm Nd:YAG solid-state laser as the excitation source in the backscattering geometry, an 1800 g/mm grating, and a thermoelectrically cooled charged coupled device as the detector.

Estimation of specific surface area

The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) of bulk and 2D V2O5 were calculated and compared. The ECSA was estimated from the non-Faradic capacitive current associated with double layer charging using the scan rate dependence of cycle voltammograms (CV)32,33. The experimental setup consists of a three-electrode system with a Pt counter electrode and Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode. In the present study, for bulk V2O5, a 5 mM dispersion of bulk V2O5 in propanol was taken. Around 630 µL was dispersed on carbon paper with dimensions of 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm. The volume of the sample dispersion was chosen to ensure a conformal coating on the carbon paper. For 2D V2O5, 250 µL of a 1 mM dispersion of exfoliated V2O5 nanosheets (45 µg of sample) in formamide was coated on a similar substrate. The CV of the samples with 1 M H2SO4 electrolyte was recorded (using PGSTAT 302 N, Metrohm Autolab e.v.), and the peak current, Ic, was taken from the non-Faradic region.

Photocatalytic study

The degradation of MB (C16H18ClN3S (Merck India)) dye was examined to understand the photocatalytic properties of the bulk material and 2D V2O5. The V2O5 catalyst mixed with the dye was subjected to UV-C (254 nm, 9 W, PL-S, PHILIPS, Poland). The intensity of the light source was measured using a Lutron UV light meter (Taiwan) at a distance of 3 cm from the light source, and the intensity was 2.21 mWcm2. An aqueous solution of dye and bulk V2O5 (concentration 0.18 mg/mL) was prepared in the dark and maintained at adsorption–desorption equilibrium. For 2D V2O5, 5 mL of 2D V2O5 dispersion (around 0.9 mg) was deposited on a quartz substrate and dipped into dye solution32. To achieve adsorption–desorption equilibrium, the sample was kept in the dark. The amount of 2D V2O5 sample was selected so that, for 5 mL of stock solution, the catalyst amount maintained the same as that for the bulk V2O5 catalyst. Light source was then exposed upon the dye solution containing the catalyst for various durations. Five milliliters of the irradiated solution was then subjected to UV‒Vis spectrometry. By monitoring the MB dye absorption peak at 664 nm, the degradation of MB dye was studied. For the quantitative study, the UV‒Vis absorption spectra of the solutions were periodically recorded.

Results and discussion

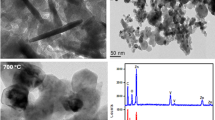

Estimation of nanosheet thickness and atomic resolution STEM studies

AFM studies were carried out on the exfoliated V2O5 sample to determine the thickness. Figure 1a shows the AFM image of evenly distributed nanosheets on a Si/SiO2 substrate. The exfoliated layers in the ensemble have lateral dimensions between 100 and 300 nm, as observed from the FESEM image (Fig. S1). The observed step height has a standard deviation of 0.1 nm. The theoretical thicknesses of the monolayer, bilayer and trilayer V2O5 nanosheets are ~ 0.43, 0.87 and 1.3 nm, respectively29. The experimentally observed thicknesses of the individual layers of 2D V2O5 nanosheets are in the range of 1.0–1.5 nm, as shown in the height profile (Fig. 1a). The numerical distribution of the nanosheet thicknesses shown in Fig. 1b indicates that the quantity of bilayer thin nanosheets in the sample is substantially greater. To verify the atomic structure and chemical composition, an atomic resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of the exfoliated nanosheets was obtained. Figure 1c and d show dark field (DF) STEM image and atomic resolution annular dark field (ADF)-STEM image of 2D nanosheets. The nanosheets in the DF-STEM image shown in Fig. 1c are folded, which is commonly observed in unsupported 2D structures34. The atomic resolution ADF image, displayed in Fig. 1d, is collected from the flat area of the individual nanosheets and demonstrates the arrangement of the VO5 square pyramidal structure in α-V2O5 along the (001) plane. The 2D layer is generated by joining the 1D chain of VO5 pyramids along the b-axis with chain oxygen (OII) along the a-axis.

(a) AFM topography and height profile of exfoliated nanosheets. (b) Distribution of the thickness of 2D V2O5 nanosheets. (c) STEM image and (d) atomic resolution annular dark field (ADF)-STEM image of 2D V2O5 nanosheets. (e) XPS survey spectrum of 2D V2O5 and (f) the core-level spectrum corresponding to the binding energies of V2p3/2 for the V5+ and V4+ states of V atoms in 2D V2O5 nanosheets. (g) UV‒Vis absorption spectra of bulk and 2D V2O5. The Tauc plot for understanding the optical band gap is given in the corresponding insets. (h) Raman spectrum of the 2D V2O5 nanosheets.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies

Figure 1e displays the XPS survey spectrum of 2D V2O5. The V2O5 phase of the exfoliated nanosheets was further validated by the observation of peaks at 517.4 (V2p3/2), 524.8 (V2p1/2), and 530.1 (O1s) in the XPS survey spectrum35. The deconvoluted peaks in the core-level spectrum observed at 517.4 and 516.3 eV corresponded to the binding energies of V2p3/2 for the V5+ and V4+ states, respectively (Fig. 1f). The peaks at 524.8 and 523.1 eV correspond to the binding energies of V2p1/2 for the V5+ and V4+ states, respectively36. The presence of the peaks corresponding to V4+ indicates the presence of oxygen vacancy sites in the samples29. The percentage of oxygen vacancy defects in 2D V2O5 was ~ 17%, as determined by the area under the curve. The presence of these oxygen vacancy sites can potentially increase the surface activity and, consequently, the catalytic property of the sample.

UV‒Vis absorption studies for estimating the optical band gap

Bulk V2O5 is a semiconductor with a bandgap of ~ 2.4 eV and a Fermi energy between the O 2p valence band and V 3d conduction band37. Within this gap, however, two localized split-off bands exist approximately 0.6 eV below the main V 3d band due to crystal field splitting37. The xy-derived levels of the conduction band are predicted to be at the lowest energies because they are not affected by vanadyl oxygen interactions. However, only two of the four xy-derived levels interact with the bridging oxygen and move up into the conduction band. Hence, the strong, indirect V-V interactions across the bridging oxygen are found to be the cause of the existence of split-off bands37. Figure 1g shows the UV‒Vis absorption spectra and Tauc plots for estimating the band gap for bulk and 2D V2O5. A significant increase in the absorbance value from 0.22 to 1.58 was seen between bulk and bilayer V2O5 (Fig. 1g). Additionally, there is a substantial increase in the optical absorbance for 2D and bulk V2O5 with the same concentration of sample and intensity of incident light. This observation is possibly due to the pronounced excitonic effects in bilayer 2D V2O5, which is also observed in other 2D materials arising out of the reduced dielectric screening effect38,39. This increase in the optical absorbance of 2D V2O5 indicates an exceptionally high number of photogenerated free charges, which can actively participate in the photocatalytic process. In addition, an absorption edge blueshift from bulk to bilayer 2D V2O5 was observed, indicating electronic decoupling with decreasing layer thickness in the 2D nanosheets of V2O529. The optical bandgap and Eg of bulk and 2D V2O5 are experimentally calculated from Tauc’s Plot to be 2.47 and 3.55 eV, respectively (Fig. 1g). These results are in agreement with our earlier report on the synthesis of 2D nanosheets of V2O529.

Raman spectroscopic analysis of bilayer 2D V2O5

The Raman spectrum of the 2D V2O5 is given in Fig. 1h. The sample exhibited nine vibrational modes corresponding to 2D V2O5. The low-frequency vibrational modes A1g and B1g at 111 and 158 cm−1, respectively, are due to chain translation along the crystallographic c- and a-axes. V‒OII‒V bending vibration causes the B3g mode at 262 cm−1. The deflection of V‒OIII and V‒OIII′ along the c direction is responsible for the vibrational mode B2g at 324 cm−1. The A1g peak at 489 cm−1 arises from the bending vibration of V‒OII‒V in the c direction. The vibration of V‒OIII′ and V‒OIII along the a-axis is the origin of the vibrational mode B1g at 713 cm−1. The highest frequency A1g mode at 1010 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of V‒OI along the c-axis29. The peak at 620 cm−1 in the Raman spectrum is expected to arise due to surface oxygen vacancies and consequent surface reduction29.

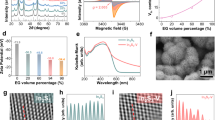

Electrochemical surface area of bulk and 2D V2O5

The specific surface area of the 2D V2O5 nanosheets was compared with that of bulk V2O5 by calculating the ECSA. The ECSA of a sample is essentially estimated from the electrochemical double-layer capacitance. The measurement can be performed either from the non-Faradic capacitive current associated with double-layer charging from the scan rate dependence of CV or from the frequency-dependent impedance of the system using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy32,39. In the present study, the first method was adopted for the measurement of the ECSA. The faradic process will be absent in the potential window of, typically, 0.1 V around the open circuit voltage. The CV curves of the samples were recorded using 1 M H2SO4 as the electrolyte. From the non-Faradic part, the peak current, Ic, is obtained. Thus, the ECSA may be determined using,

where Cs is the specific capacitance of an atomically smooth planar surface of the material per unit area under identical electrolyte conditions. For the 1 M H2SO4 electrolyte, the Cs were found to be 0.035 mF/cm32,39,40. Figure 2a and b show CV diagrams of bulk and 2D V2O5, respectively. The values of the double layer capacitance (Cdl) are 1.29 mF for bulk, as shown in Fig. 2c, and 3.32 mF for 2D V2O5, as shown in Fig. 2d. The corresponding ECSAs per 1 g of bulk and 2D V2O5 were determined to be 6.5 and 211 m2/g, respectively (Fig. 2e). According to the literature, bulk V2O5 has a shallow specific surface area < 10 m2/g31,32. Thus, the observed specific surface area of bulk V2O5 is in agreement with the literature. This study revealed that, in comparison with the bulk equivalent, 2D nanosheets of V2O5 exhibited an increase in specific surface area of approximately 32 times.

Degradation of MB dye under UV irradiation

The photodegradation of MB dye was studied using bulk and 2D V2O5 as catalysts. The UV‒Vis absorption spectra of aqueous dye solutions collected at various UV light exposure times containing the bulk and 2D V2O5 catalysts are displayed in Fig. 3a and b. The benzene ring and heteropoly aromatic bond of the MB dye molecule are broken upon exposure to UV light in the presence of the catalyst, which is apparent from the decrease in the strength of the absorption peak at 662 and 608 nm32,41. As a result, upon exposure to UV light in the presence of the catalyst, the dye molecules undergo degradation. The amount of catalyst was kept the same for all bulk and 2D V2O5 samples for the same amount of dye solution. The photodegradation of MB dye under UV light exposure without any catalysts was also tested and is shown in Fig. S2 (Supplementary information). The degradation of MB dye using 2D and bulk V2O5 catalysts was also studied under exposure to visible light, and the results are shown in the supplementary information (Fig. S3). Only ~ 5% of the dye underwent degradation with a UV light exposure of 160 min. As shown in Fig. 3a and b, the bulk V2O5 catalyst caused only minimal degradation of 7.7% after 35 min of UV exposure of the dye (16 ppm), whereas 2D V2O5 catalyst resulted in the degradation of ~ 99% in just 3 min.

UV‒Vis absorption spectra of MB dye solutions for different durations with (a) bulk V2O5 and (b) 2D V2O5 as catalysts. (c) The curve of ln(C0/Ct) vs. light exposure time (d) Dye degradation efficiency using the bulk and 2D V2O5 samples as catalysts versus the duration of light exposure. (e) Schematic of dye degradation mechanism of 2D V2O5.

Estimation of the rate constant and efficiency of dye degradation

Generally, the degradation obeys pseudo-first-order kinetics32,41,42, and according to the observations, the degradation reaction fits well with the equation \(\text{ln}\frac{{C}_{0}}{{C}_{t}}=kt\), where C0 is the absorption at t = 0, and Ct is the absorption after the time interval t of the irradiation (Fig. 3c). Based on Fig. 3c, the rate constants for dye degradation using the bulk and exfoliated V2O5 catalysts were calculated. The 2D and bulk V2O5 catalysts exhibit distinct rate constants for the degradation of MB dye: 2.311 min−1 and 0.0023 min−1, respectively.

The percentage (%) of photocatalytic dye degradation efficiency was calculated using Eq. (2)43.

Figure 3d depicts the effect of light exposure duration on degradation efficiency. As discussed in the previous sections, the specific surface areas (ECSA) of the bulk and 2D V2O5 are 6.5 and 211 m2/g, respectively. As a result of this increase in the specific surface area, the photocatalytic performance of the 2D nanosheets substantially improved compared with that of the bulk V2O5 catalyst. In addition, surface oxygen vacancies can act as active sites for redox reactions and enhance surface activity. A comparison of the reported literature with the present study (Table 1) also indicates the superior catalytic performance of 2D V2O5 nanosheets.

Effect of scavenging agents on dye degradation

The MB dye contains active sites for oxidative attack. To understand the active oxidative species involved in the catalytic process, the effects of scavenging reagents in quenching superoxide (\({\text{O}}_{2}^{-}\)) and hydroxyl (·OH) radicals during the catalytic process were studied. p-Benzoquinone and isopropanol were used as the scavenging reagents for superoxide (\({\text{O}}_{2}^{-}\)) and hydroxyl (·OH) radicals, respectively. p-benzoquinone and isopropanol were added at concentrations of 10 mM and 20 mM, respectively. The catalytic degradation of the MB dye molecule was studied using the same method as described in the previous sections. Figure S3a and b show the UV‒Vis absorption spectra of MB dye molecules in the presence of the 2D V2O5 catalyst and the scavengers p-benzoquinone and isopropanol, respectively. Figure 4a and b show the rate constants obtained in the presence of p-benzoquinone and isopropanol, respectively. The rate constant of the catalytic degradation of MB dye decreased to 0.01 min−1 in the presence of p-benzoquinone, while it decreased to 2.31 min−1 without any scavengers. In the presence of isopropanol, the rate constant decreased to 0.04 min−1 during the first 18 min of UV light illumination, followed by a rate constant of 0.13 min−1. This change in the rate constant is due to the decrease in the isopropanol concentration due to evaporation. In the presence of both scavenging reagents, a significant reduction in the rate constant is observed. The change in rate constant indisputably proves that the .\({\text{O}}_{2}^{-}\) and ·OH radicals are involved in the photocatalytic reaction.

Mechanism of photocatalytic degradation of MB dye

Figure 3e shows a schematic illustration of a possible pathway for the photocatalytic degradation of MB dye. When 2D V2O5 nanosheets are exposed to UV light, electrons are excited to the conduction band (CB), leaving holes in the valence band (VB). ·OH radicals are generated when these holes interact with OH− on the catalyst surface. These electrons lead to the production of \({\text{O}}_{2}^{-}\) superoxide anion radicals. The effect of scavengers on dye degradation has demonstrated that the oxidizing species in the photocatalysis reaction are ·OH and .\({\text{O}}_{2}^{-}\) radicals that are thereby produced. According to the results, the use of 2D V2O5 nanosheets effectively improved the separation of electrons and holes, which substantially enhanced the photocatalytic activity. The anticipated decrease in the screening effect of charges and the presence of excitonic levels in 2D materials could also be responsible for this enhanced separation of electrons and holes54 in 2D V2O5.

Recyclability of the catalyst

The recyclability of the 2D V2O5 catalyst was determined by reusing a 2D V2O5 sample coated on a quartz substrate. After each cycle, the sample on the substrate was collected, washed with deionized water (Millipore), and dried at 80 °C. Figure 5a shows the degradation efficiency of the catalyst under UV light illumination, and Fig. 5b shows the degradation efficiency of the 2D V2O5 catalyst under UV light illumination for 3.5 min over three cycles. The decrease in efficiency can be due to the loss of catalyst from the substrate during the recycling process.

Conclusions

2D V2O5 nanosheets with a bilayer thickness were synthesized using a chemical exfoliation technique, which showed a ~ 30-fold increase in the specific surface area from that of the bulk. The catalytic activity of 2D V2O5 was studied in detail and compared with that of bulk V2O5. A considerable improvement in the degradation rate constant was observed for 2D V2O5 from bulk V2O5 catalysts. The rate constants for the bulk and 2D V2O5 catalysts were 0.0023 and 2.311 min−1, respectively. The sizable improvement in the catalytic activity is attributed to three properties:

-

a.

A massive increase in the specific surface area of 2D nanosheets from bulk V2O5 was observed as a result of the formation of nanosheets with thicknesses down to the bilayer.

-

b.

The presence of oxygen vacancies acts as an active site for redox reactions, improving the surface activity.

-

c.

An increase in the optical absorption coefficient on the order of ~ 7 times substantiates a significant increase in the number of photoexcited electrons. The efficient separation of photogenerated carriers facilitates the generation of free radicals responsible for the oxidative decomposition of organic dye molecules.

The results obtained from the present study undeniably prove that the novel 2D V2O5 nanosheet is a promising photocatalyst. In addition, the 2D V2O5 catalyst is stable and abundant on earth, the catalyst is recyclable, and the synthesis method of the catalyst is cost effective. Additionally, the current study opens up new possibilities for using 2D V2O5 as electro- and photocatalyst because of its improved surface and optical properties. The increase in optical absorption leads to the possibility of efficiently generating hot electrons, creating novel possibilities for light energy conversion to electrical and chemical energy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Deng, D. et al. Catalysis with two-dimensional materials and their heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.340 (2016).

Babar, Z. U., Raza, A., Cassinese, A. & Iannotti, V. Two dimensional heterostructures for optoelectronics: Current status and future perspective. Molecules 28, 2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28052275 (2023).

Ali, S. et al. Recent advances in 2D-MXene based nanocomposites for optoelectronics. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2200556. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.202200556 (2022).

Raza, A. et al. Photoelectrochemical energy conversion over 2D materials. Photochemistry 2, 272–298. https://doi.org/10.3390/photochem2020020 (2022).

Hassan, J. Z. et al. 2D material-based sensing devices: An update. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 6016–6063. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2TA07653E (2023).

Raza, A., Qumar, U., Rafi, A. A. & Ikram, M. MXene-based nanocomposites for solar energy harvesting. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 33, e00462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2022.e00462 (2022).

Raza, A., Rafi, A. A., Hassan, J. Z., Rafiq, A. & Li, G. Rational design of 2D heterostructured photo- & electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 15, 100402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2023.100402 (2023).

Devarayapalli, K. C. et al. Mesostructured g-C3N4 nanosheets interconnected with V2O5 nanobelts as electrode for coin-cell-type-asymmetric supercapacitor device. Mater. Today Energy 21, 100699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtener.2021.100699 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Measuring the specific surface area of monolayer graphene oxide in water. Mater. Lett. 261, 127098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2019.127098 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. 3D honeycomb-like structured graphene and its high efficiency as a counter-electrode catalyst for dye-sensitized solar cells. Angew. Chem. 52, 9210–9214. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201303497 (2013).

Nakada, K. et al. Edge state in graphene ribbons: Nanometer size effect and edge shape dependence. Phys. Rev. B 54, 17954–17961. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.54.17954 (1996).

Zhao, L. et al. A critical review on new and efficient 2D materials for catalysis. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2200771. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.202200771 (2022).

Kumari, H. et al. A review on photocatalysis used for wastewater treatment: Dye degradation. Water Air Soil Pollut. 234, 349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-023-06359-9 (2023).

Javaid, R. et al. Catalytic oxidation process for the degradation of synthetic dyes: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 2066. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16112066 (2019).

Kapoor, R. T. et al. Exploiting microbial biomass in treating azo dyes contaminated wastewater: Mechanism of degradation and factors affecting microbial efficiency. J. Water Process Eng. 43, 102255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.102255 (2021).

Védrine, J. C. Metal oxides in heterogeneous oxidation catalysis: State of the art and challenges for a more sustainable world. ChemSusChem 12, 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201802248 (2019).

Beaula Ruby Kamalam, M. et al. Direct sunlight-driven enhanced photocatalytic performance of V2O5 nanorods/graphene oxide nanocomposites for the degradation of Victoria blue dye. Environ. Res. 199, 111369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111369 (2021).

Sahu, B. K. et al. Interface of GO with SnO2 quantum dots as an efficient visible-light photocatalyst. Chemosphere 276, 130142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130142 (2021).

Fu, M. et al. Sol–gel preparation and enhanced photocatalytic performance of Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 1587–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2011.10.003 (2011).

Agorku, E. S., Kuvarega, A. T., Mamba, B. B., Pandey, A. C. & Mishra, A. K. Enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity of multielements-doped ZrO2 for degradation of indigo carmine. J. Rare Earths 33, 498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0721(14)60447-6 (2015).

Hosseini, Z. S. et al. Enhanced visible photocatalytic performance of undoped TiO2 nanoparticles thin films through modifying the substrate surface roughness. Mater. Chem. Phys. 279, 125530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2021.125530 (2022).

Shi, Q., Zhang, X., Li, Z., Raza, A. & Li, G. Plasmonic Au Nanoparticle of a Au/TiO2–C3N4 heterojunction boosts up photooxidation of benzyl alcohol using LED light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 30161–30169. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c03451 (2023).

Bahlawane, N. et al. Vanadium oxide compounds: Structure, properties, and growth from the gas phase. Chem. Vapor Deposit. 20, 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/cvde.201400057 (2014).

Ek, M. et al. Visualizing atomic-scale redox dynamics in vanadium oxide-based catalysts. Nat. Commun. 8, 305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00385-y (2017).

Haber, J. et al. The structure and redox properties of vanadium oxide surface compounds. J. Catal. 102, 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9517(86)90140-5 (1986).

Alfaro Cruz, M. R. et al. Hierarchical V2O5 thin films and its photocatalytic performance. Mater. Lett. 324, 132751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2022.132751 (2022).

Shanmugam, M. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of the graphene-V2O5 nanocomposite in the degradation of methylene blue dye under direct sunlight. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 14905–14911. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b02715 (2015).

Le, T. K. et al. Relation of photoluminescence and sunlight photocatalytic activities of pure V2O5 nanohollows and V2O5/RGO nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 100, 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2019.04.047 (2019).

Radhakrishnan, R. P. et al. Electronic and vibrational decoupling in chemically exfoliated bilayer thin two-dimensional V2O5. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 9821–9829. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c02637 (2021).

Wachs, I. E. Catalysis science of supported vanadium oxide catalysts. Dalton Trans. 42, 11762–11769. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3DT50692D (2013).

Rui, X. et al. Ultrathin V2O5 nanosheet cathodes: Realizing ultrafast reversible lithium storage. Nanoscale 5, 556–560. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2NR33422D (2013).

Reshma, P. R. 2D V2O5 nanosheets for photocatalytic and advanced energy storage applications. IGC Newsl. 133, 4–8 (2022).

McCrory, C. C. L. et al. Benchmarking heterogeneous electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16977–16987. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja407115p (2013).

Meyer, J. C. et al. The structure of suspended graphene sheets. Nature 446, 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05545 (2007).

Basu, R. et al. Role of vanadyl oxygen in understanding metallic behavior of V2O5(001) nanorods. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 26539–26543. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b08452 (2016).

Wu, Q.-H. et al. Photoelectron spectroscopy study of oxygen vacancy on vanadium oxides surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 236, 473–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2004.05.112 (2004).

Lambrecht, W. et al. On the origin of the split-off conduction bands in V2O5. J. Phys. C 32, 4785. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3719/14/32/015 (1981).

Mak, K. F. et al. Tightly bound trions in monolayer MoS2. Nat. Mater. 12, 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3505 (2013).

Madapu, K. K. & Dhara, S. Laser-induced anharmonicity vs thermally induced biaxial compressive strain in mono- and bilayer MoS2 grown via CVD. AIP Adv. 10, 085003. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0001863 (2020).

Trasatti, S. et al. Real surface area measurements in electrochemistry. AIP Adv. 63, 711–734. https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199163050711 (1991).

Liu, X. et al. Visible light photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by SnO2 quantum dots prepared via microwave-assisted method. Catal. Sci. Technol. 3, 1805–1809. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CY00013C (2013).

Chen, F. et al. A facile route for the synthesis of ZnS rods with excellent photocatalytic activity. Chem. Eng. J. 234, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.08.075 (2013).

Jin, X. et al. Influences of synthetic conditions on the photocatalytic performance of ZnS/graphene composites. J. Alloys Compd. 780, 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.11.271 (2019).

Mishra, A. et al. Rapid photodegradation of methylene blue dye by rGO-V2O5 nano composite. J. Alloys Compd. 842, 155746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155746 (2020).

Aawani, E. et al. Synthesis and characterization of reduced graphene oxide–V2O5 nanocomposite for enhanced photocatalytic activity under different types of irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 125, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2018.09.028 (2019).

Jayaraj, S. K. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of V2O5 nanorods for the photodegradation of organic dyes: A detailed understanding of the mechanism and their antibacterial activity. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 85, 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2018.06.006 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Growth of oriented vanadium pentaoxide nanostructures on transparent conducting substrates and their applications in photocatalysis. J. Solid State Chem. 214, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2013.10.020 (2014).

Jenifer, A. et al. Photocatalytic dye degradation of V2O5 nanoparticles: An experimental and DFT analysis. Optik 243, 167148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.167148 (2021).

Fauzi, M. et al. The effect of various capping agents on V2O5 morphology and photocatalytic degradation of dye. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 32, 10473–10490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-021-05703-1 (2021).

Yadav, A. A., Hunge, Y. M., Kang, S.-W., Fujishima, A. & Terashima, C. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation activity using the V2O5/RGO composite. Nanomaterials https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13020338 (2023).

Vattikuti, S. V. P., Nam, N. D. & Shim, J. Graphitic carbon nitride/Na2Ti3O7/V2O5 nanocomposite as a visible light active photocatalyst. Ceram. Int. 46, 18287–18296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.05.045 (2020).

Vattikuti, S. V. P., Reddy, P. A. K., NagaJyothi, P. C., Shim, J. & Byon, C. Hydrothermally synthesized Na2Ti3O7 nanotube–V2O5 heterostructures with improved visible photocatalytic degradation and hydrogen evolution: Its photocorrosion suppression. J. Alloys Compd. 740, 574–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.12.371 (2018).

Kabir, M. H. et al. The efficacy of rare-earth doped V2O5 photocatalyst for removal of pollutants from industrial wastewater. Opt. Mater. 147, 114724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2023.114724 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Tailoring of electronic and surface structures boosts exciton-triggering photocatalysis for singlet oxygen generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2114729118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2114729118 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. K Ganesan for the AFM studies and Dr. Shyam Kanta Sinha and Dr. Arup Das Gupta for the TEM studies. The authors also thank Dr. A. Das and Ms. Reshma T S for fruitful discussions. We also acknowledge the Director, MSG, and the Director, IGCAR, for their encouragement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The central idea was conceived by R.P.R. and A.K.P. Sample synthesis, characterization, and data analysis were carried out by R.P.R. The manuscript was written by R.P.R., and all the authors discussed the results and the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reshma, P.R., Prasad, A.K. & Dhara, S. Novel bilayer 2D V2O5 as a potential catalyst for fast photodegradation of organic dyes. Sci Rep 14, 14462 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65421-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65421-6

This article is cited by

-

High performance bilayer 2D V2O5 cathode for Zn-ion and Zn/Li hybrid metal-ion intercalation battery

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Structural, Optical, Catalytic, and Pigment Properties of Ca-Doped V2O5 Nanostructures

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2025)